Abstract

There is little understanding of mechanisms underlying the assembly and release of infectious hepatitis C virus (HCV) from cultured cells. Cells transfected with synthetic genomic RNA from a unique genotype 2a virus (JFH1) produce high titers of virus, while virus yields are much lower with a prototype genotype 1a RNA containing multiple cell culture-adaptive mutations (H77S). To characterize the basis for this difference in infectious particle production, we constructed chimeric genomes encoding the structural proteins of H77S within the background of JFH1. RNAs encoding polyproteins fused at the NS2/NS3 junction (“H-NS2/NS3-J”) and at a site of natural, intergenotypic recombination within NS2 [“H-(NS2)-J”] produced infectious virus. In contrast, no virus was produced by a chimera fused at the p7-NS2 junction. Chimera H-NS2/NS3-J virus (vH-NS2/NS3-J) recovered from transfected cultures contained compensatory mutations in E1 and NS3 that were essential for the production of infectious virus, while yields of infectious vH-(NS2)-J were enhanced by mutations within p7 and NS2. These compensatory mutations were chimera specific and did not enhance viral RNA replication or polyprotein processing; thus, they likely compensate for incompatibilities between proteins of different genotypes at sites of interactions essential for virus assembly and/or release. Mutations in p7 and NS2 acted additively and increased the specific infectivity of vH-(NS2)-J particles, while having less impact on the numbers of particles released. We conclude that interactions between NS2 and E1 and p7 as well as between NS2 and NS3 are essential for virus assembly and/or release and that each of these viral proteins plays an important role in this process.

Tremendous progress has been made in the development of cell culture systems that support the replication of hepatitis C virus (HCV) (10, 19, 24, 25), a hepatotropic flavivirus that accounts for much human morbidity and mortality (17). These advances offer new insights into the biology of this important pathogen and will also facilitate the development of vaccines and therapeutic antiviral drugs. Two specific developments have contributed to this progress: the identification of the Huh7 hepatoma-derived cell lines that are permissive for HCV replication (2, 11) and the construction of HCV cDNA clones that, when transcribed into RNA and transfected into these cells, initiate a complete viral replication cycle leading to the release of infectious particles (10, 19, 24, 25). Most notably, synthetic RNA derived from JFH1 virus, a genotype 2a HCV recovered from a Japanese patient with fulminant hepatitis C (8), demonstrates extraordinary replication capacity in the absence of cell culture-adaptive mutations, resulting in the release of infectious virus particles within 48 h of transfection (19, 25). RNA derived from a prototype genotype 1a HCV, H77, containing five cell culture-adaptive mutations (H77S) also produces infectious virus when transfected into Huh7 cells (24). H77S-transfected cells release 100- to 1,000-fold less infectious virus than JFH1, but this genotype 1a genome is more representative of the HCV strains that are prevalent in persons with HCV-related liver diseases.

While the construction of a wholly genotype 2a chimera was highly successful, initial reports suggested that an intergenotypic chimera encoding the core NS2 proteins of the genotype 1a H77 virus within the genotype 2a JFH1 background was incapable of producing infectious virus (10). In contrast, we have found that viable intergenotypic chimeras are possible. Pietschmann et al. (16) recently reported similar results. However, we noted variable delays in the production of infectious virus following the transfection of different chimeric RNAs into Huh7 cells, suggesting various requirements for compensatory mutations to achieve efficient release of cell culture-infectious particles. Here, we show that efficient production of cell culture-infectious virus by intergenotypic chimeric RNAs containing sequences derived from the H77 and JFH1 viruses requires mutations within the E1, p7, NS2, and/or NS3 protein that contribute to the ability of these chimeras to assemble and release infectious virus particles. These mutations act independently of any effect on viral RNA replication or polyprotein processing, indicating that these proteins have essential (and in the case of NS3, previously unrecognized) interactions and functions related to the assembly and release of infectious HCV.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids.

pH77S (24) and pJFH1 (19) have been described previously. Similar plasmids containing chimeric HCV genomic sequences with segments derived from pH77S (structural proteins with or without p7 and/or NS2) and pJFH1 (nonstructural proteins and nontranslated RNA sequences) (Fig. 1A) were constructed as follows. (Nucleotide positions are referred to according to their position in the parental pH77S [24] or pJFH1 [19] cDNA clones, since the numbers of residues within the H77S and JFH1 polyproteins differ.) To construct the H-p7/NS2-J chimera, an NsiI restriction enzyme site was generated at the junction of the p7 and NS2 coding regions in pH77S by the introduction of two silent, single base changes, C2765T and C2769T, yielding pH77S-NsiI. This was accomplished by QuikChange mutagenesis (Stratagene). Similarly, an NsiI site was created in the corresponding region of pJFH1 by the introduction of a single C2779A mutation (pJFH1-NsiI). The EcoRI/ApaLI fragment of pJFH1, the ApaLI/NsiI fragment of pH77S-NsiI, and the NsiI/SpeI (nucleotide [nt] 4105) fragment of pJFH1-NsiI were then ligated into pUC20 vector DNA digested with EcoRI and XbaI. The resulting plasmid was digested with EcoRI/AvrII (nt 3866), and the fragment containing the JFH1 5′NTR-NS3 sequence (with inserted H77S sequence) was ligated to the EcoRI/AvrII fragment of pJFH1 containing the remainder of the genome, resulting in pH-p7/NS2-J. A similar strategy was used to construct pH-NS2/NS3-J and pH-(NS2)-J. For pH-NS2/NS3-J, we introduced an MluI restriction site at the 10th to 11th codons of the NS3 sequence. We selected this position since the N-terminal 15 amino acids of NS3 are identical in H77S and JFH1 and because this does not alter the amino acid sequence of the polyprotein. Silent, single base substitutions A3450C and A3452T were introduced into pH77S, and substitutions A3460G and A3463T were introduced into pJFH1 to produce pH77S-MluI and JFH1-MluI, respectively. Subsequent steps to construct pH-NS2/NS3-J were similar to those described above, except that the ApaLI/MluI fragment of H77S-MluI and the MluI/SpeI fragment of pJFH1-MluI were ligated in the subcloning step. To construct pH-(NS2)-J, we introduced a SnaBI restriction site into pH77S by inserting two silent, single base changes, C3179T and C3182G, to produce H77S-SnaBI. Similarly, two silent base substitutions, C3190T and C3193G, were introduced into pJFH1 to make pJFH1-SnaBI. Subsequent steps for the construction of pH-(NS2)-J were as described above, except that the ApaLI/SnaBI fragment of pH77S-Sna BI and the SnaBI/SpeI fragment of pJFH1-SnaBI were used in the subcloning step. Each of the introduced base changes was verified by DNA sequence analysis.

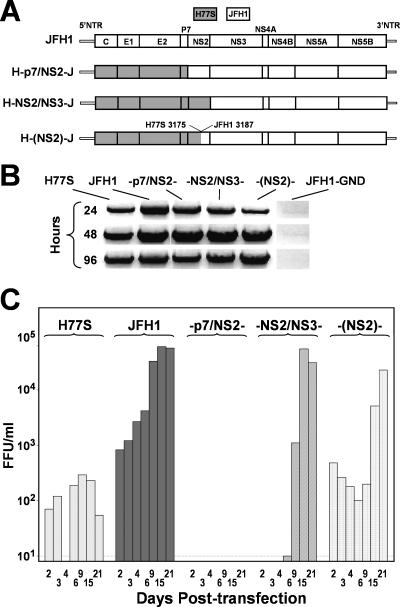

FIG. 1.

Production of infectious virus by chimeric HCV RNAs encoding genotype 1a (H77S) structural proteins within the background of genotype 2a (JFH1) virus. (A) Organization of the chimeric RNAs, which are labeled according to the location of the chimeric junction. Proteins encoded by H77S-derived sequence are shaded. Nontranslated RNA (NTR) segments are from JFH1. (B) Products of semiquantitative RT-PCR assays for HCV RNA in lysates of RNA-transfected FT3-7 cells. The JFH1-GND RNA contains a replication-lethal mutation in NS5B (19). (C) Infectious virus released by transfected FT3-7 cells was measured by inoculating dilutions of cell culture supernatant fluids, collected at the times indicated posttransfection, onto naïve Huh-7.5 cells. The detection limit was 10 FFU/ml.

Cells.

Huh7 cells and Huh-7.5 cells (a generous gift from Charles Rice) were cultured as described previously (24). The FT3-7 cell line is a clonal derivative of Huh7 cells obtained following transformation with a Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) expression vector (unpublished data). These cells express a very low abundance of TLR3 but nonetheless produce more infectious virus than other Huh-7.5 cells (data not shown). Other details of cell cultures were as described previously (24).

HCV RNA transfection and virus production.

HCV RNAs were transcribed in vitro and electroporated into cells as described previously (23, 24). In brief, 10 μg of in vitro-synthesized HCV RNA was mixed with 5 × 106 FT3-7 or Huh-7.5 cells in a 2-mm cuvette and pulsed twice at 1.4 kV and 25 μF. Cells were seeded into 12-well plates for HCV RNA analysis or into 6-well plates for HCV protein analysis. For virus production, transfected cells were seeded into 25-cm2 flasks and fed with medium containing 10% fetal calf serum. Cells were passaged at 3- to 4-day intervals posttransfection by trypsinization and reseeding with a 1:3 to 1:4 split into fresh culture vessels.

Quantitation of HCV RNA.

Viral RNA was detected by either a semiquantitative or a quantitative TaqMan reverse transcription (RT)-PCR assay (24). Total RNA was isolated from cell lysates using an RNeasy kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. RNA was isolated from cell culture supernatants and gradient fractions using a QIAamp viral RNA kit (QIAGEN). For monitoring RNA replication in transfected cells, we used a semiquantitative long-range RT-PCR assay carried out using reagents provided with a OneStep RT-PCR kit (QIAGEN) (24). In brief, 1 to 3 μl of RNA was reverse transcribed in a 50-μl reaction mixture at 45°C for 30 min, followed by inactivation of the reverse transcriptase at 95°C for 15 min. Products were then amplified by PCR for 30 cycles each, comprising 94°C for 30 s and 68°C for 2 min 30 s. Primer sets targeted the JFH1 NS3 coding regions. JFH1 primers (nt 3460 to 5322) were 5′-ACGAGGCCTCCTGGGCGCCATAGTGGTGAGTATGACG-3′ and 5′-GTCATGACCTCAAGGTCAGCTTGCATGCATGTGGCG-3′. RT-PCR amplification of cellular GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) mRNA in parallel control reaction mixtures used the primer sets KpnI-GAPDH-s (CGGGGTACCCATGGGGAAGGTGAAGGTCG) and 763-GAPDH-as (ACCTTCTTGATGTCATCATA). Alternatively, quantitative real-time TaqMan RT-PCR analysis was carried out using the following primer pairs and a probe targeting a conserved 221-base sequence within the 5′ nontranslated RNA segment of the genome: HCV84FP (GCCATGGCGTTAGTATGAGTGT), HCV JFH_303RP (CGCCCTATCA GGCAGTACCACAA), and HCV146BHQ (FAM [6-carboxyfluorescein]-TCTGCGGAACCGGTGAGTACACC-DBH1) (24). TaqMan assays utilized reagents provided with the EZ RT-PCR Core Reagent kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and an ABI Prism 7700 instrument. Reaction mixtures were incubated at 50°C for 2 min, 60°C for 45 min, and 95°C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 20 s and 60°C for 1 min.

HCV infectivity assays.

A 100-μl aliquot of serial 10-fold dilutions (generally 1:2 to 1:2,000) of cell culture supernatant fluids (clarified by low-speed centrifugation) or iodixanol gradient fractions (see below) were inoculated onto naïve Huh-7.5 cells seeded 24 h previously into 8-well chamber slides (Nalge Nunc, Rochester, NY) at 2 × 104 cells/well. Cells were maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2 environment and fed with 200 μl of medium 24 h later. Following 24 h of additional incubation, cells were fixed in methanol-acetone (1:1) at room temperature for 9 min and then stained with monoclonal antibody C7-50 to core protein (1:300), followed by extensive washing and staining with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody diluted 1:100. Clusters of infected cells staining for core antigen were considered to constitute a single infectious focus-forming unit (FFU) as described previously (24). Infectivity titers (FFU/ml) were calculated from the results of sample dilutions, yielding 5 to 100 FFU. This assay generates a strong direct linear correlation between a sample dilution and the FFU count (mean R2 = 0.998), attesting to its validity.

Analysis of chimeric viral nucleotide sequences.

HCV RNA was extracted from RNA-transfected or virus-infected cells (as indicated), converted to cDNA, and amplified by PCR using a series of oligonucleotide primers spanning the polyprotein-coding segment of the virus as described previously (22, 23). First-strand cDNA synthesis was carried out with Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Gibco-BRL); Pfu-Turbo DNA polymerase (Stratagene) was used for PCR amplification of the DNA, as described previously (23). The amplified DNAs were subjected to direct sequencing using an ABI 9600 automatic DNA sequencer.

Immunoblotting of viral proteins.

Immunoblots of cell lysates were incubated with antibody to core (C7-50, 1:30,000; Affinity BioReagents, Golden, CO) or NS3 (BDI371, 1:20,000; Biodesign, Saco, ME), followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (catalog no. 1030-05, 1:30,000; Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL). Proteins were visualized by chemiluminescence using reagents provided with the ECL Advance kit (Amersham Biosciences, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom).

Equilibrium ultracentrifugation of HCV particles.

Two days following the electroporation of cells with HCV RNA, the cell culture medium was changed to serum-free medium. Twenty-four hours later, supernatant fluids were collected, clarified by low-speed centrifugation, and concentrated ∼10-fold using a Centricon PBHK Centrifugal Plus-20 filter unit with an Ultracel PL membrane (100-kDa exclusion) (Millipore, Billerica, MA) and then layered on top of a preformed, continuous 10 to 40% iodixanol (OptiPrep, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) gradient prepared in Hanks balanced salt solution (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Gradients were centrifuged in a Beckman SW60 rotor (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA) at 45,000 rpm for 16 h at 4°C, and nine fractions (500 μl each) were collected from the top of the tube. The density of each fraction was estimated by weighing a 100-μl aliquot of each fraction.

In vitro translation.

For in vitro translation of HCV polyprotein segments, 1 μg of in vitro-transcribed RNA was used to program in vitro translation reactions in rabbit reticulocyte lysate (Promega) in a 50-μl reaction mixture containing 2 μl of [35S]methionine (1,000 Ci/mmol at 10 mCi/ml) and 1 μl of an amino acid mixture lacking methionine at 30°C for the indicated time. Reactions were stopped by the addition of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer and boiling for 10 min. Where indicated, 2.5-μl volumes of canine pancreatic microsomal membranes (Promega) were added to reaction mixtures. Translation products were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), followed by autoradiography.

RESULTS

Replication of intergenotypic chimeric HCV genomic RNA.

To map genetic determinants responsible for the efficient production of cell culture-infectious HCV particles by the JFH1 genome, we constructed a series of chimeric cDNAs encoding H77S structural and JFH1 nonstructural proteins (Fig. 1A). As the NS2/NS3 cis cleavage of the polyprotein is important for RNA replication (20) and could be influenced by the location of the intergenotypic junction, we constructed three different chimeric cDNAs: H-p7/NS2-J, in which the core p7 segment of H77 is fused to the NS2-NS5B region of JFH1; H-NS2/NS3-J, in which the core NS2 segment of H77 is fused to NS3-NS5B of JFH1; and H-(NS2)-J, in which the intergenotypic fusion is located within NS2 at residue 947 of the H77 polyprotein (residue 951 of JFH1), modeling a naturally occurring, intergenotypic 2k/1b recombinant (7). In each chimera, 5′ and 3′ nontranslated RNA sequences were derived from JFH1.

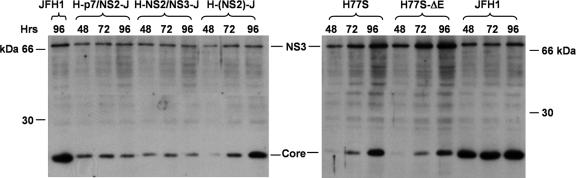

Synthetic RNAs transcribed in vitro from these constructs were electroporated into FT3-7 cells (a clonal Huh7 subline, see Materials and Methods), and RNA replication was assessed by semiquantitative RT-PCR assay (24) (Fig. 1B). We studied RNAs derived from the parental JFH1 and H77S clones in parallel. Transfected cells were passaged at 3- to 4-day intervals, as described in Materials and Methods. Each of the chimeric RNAs replicated efficiently, producing a readily detectable RNA product by 24 h posttransfection. In contrast, no viral RNA was detected in cells transfected with a JFH1 mutant bearing a lethal mutation in NS5B (JFH1-GND) (19). At 24 h, the RNA abundance was highest for JFH1, followed by the H-p7/NS2-J and H-NS2/NS3-J chimeras, H77S, and H-(NS2)-J, but by 48 h, the abundance of each chimeric RNA was similar to that of JFH1. However, core protein expression for each chimera, assessed by immunoblotting using monoclonal antibody directed against a conserved epitope, was significantly lower than that for JFH1 at 48 to 96 h posttransfection (Fig. 2). Little increase in core abundance was observed between 48 and 96 h, except in cells transfected with the H-(NS2)-J chimera, in which core abundance increased substantially, as demonstrated previously for H77S (24) (Fig. 2). NS3 showed similar trends in expression (Fig. 2). These results confirm the replication competence of each of the chimeras. However, the replication kinetics may vary slightly among the chimeras, with H-(NS2)-J showing somewhat slower initial RNA and protein accumulation than H-p7/NS2-J and H-NS2/NS3-J.

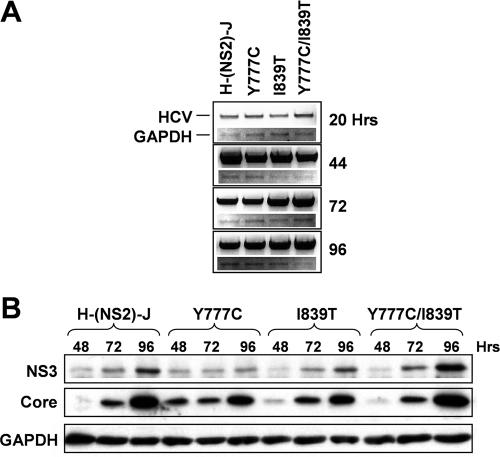

FIG. 2.

Immunoblot detection of HCV core and NS3 proteins at 48, 72, and 96 h following transfection of cells with the indicated chimeric (A) and parental (B) viral RNAs (24).

Production of infectious virus by chimeric RNAs.

We monitored the release of infectious virus particles from RNA-transfected FT3-7 cells by inoculating supernatant culture fluid samples onto naïve Huh-7.5 cells. The latter cells are highly permissive for HCV infection, due in part to defective interferon induction pathways (18). Inoculated cultures were examined for foci of cells expressing HCV antigen by using indirect immunofluorescence, as described in Materials and Methods. As reported previously (24), cells transfected with H77S RNA released low levels of infectious virus, with no increase in virus yield over the 21 days following transfection (Fig. 1C). In contrast, JFH1-transfected cells released 10-fold more virus by day 2 posttransfection and demonstrated a further ∼100-fold increase in virus yield over the subsequent 13 days. The chimeric RNAs showed intermediate patterns of virus production. The H-NS2/NS3-J chimera did not produce detectable virus (vH-NS2/NS3-J) until approximately 1 week after the transfection of FT3-7 cells (2 weeks for transfected Huh-7.5 cells, data not shown), but virus yields reached levels equal to that of JFH1-transfected cells by day 15. The H-(NS2)-J chimera produced at least as much virus as H77S by day 2 posttransfection, but vH-(NS2)-J yields substantially increased between days 9 and 15 (Fig. 1C). These results were reproducible in replicated experiments, indicating that they reflect specific characteristics of the chimeras. In both cases, the kinetics of virus release suggested that chimeric RNAs may have accumulated compensatory mutations that enhanced the yield of infectious particles. In marked contrast, no infectious virus was detected in the supernatant fluids of H-p7/NS2-J-transfected FT7-3 cells over a period of 21 days (Fig. 1C). The sensitivity of detection in these assays approximated 10 FFU per ml. As described previously for H77S virus produced in cell culture (24), vH-NS2/NS3-J and vH-(NS2)-J were effectively neutralized by sera from patients acutely infected with genotype 1 virus as well as by a murine antibody to CD81 (data not shown).

Compensatory mutations enhance virus production by chimeric RNAs.

To determine whether the accumulation of specific compensatory mutations accounted for >1,000-fold and ∼100-fold increases in vH-NS2/NS3-J and vNS2 release, respectively, observed by 2 weeks after RNA transfection (Fig. 1C), we determined the consensus sequence of the polyprotein-coding region of both chimera viruses following three cell-free passages. This was accomplished by reverse transcription of RNA isolated from infected cells and sequencing of RT-PCR products derived from it, as described in Materials and Methods. We identified two mutations within vH-NS2/NS3-J, one located near the C terminus of E1, Y361H, and another within NS3, Q1251L (residues are numbered according to their positions within the original H77 and JFH1 polyprotein segments). RNA bearing a third mutation, I1162V, was present as a minor species. Similarly, we found two mutations in vH-(NS2)-J, one located within the p7 coding region, Y777C, and the other within the N-terminal, H77-derived segment of NS2, I839T (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Mutations identified in the core-NS2 polyprotein sequence of vH-(NS2)-J

| Residuea | Mutation found after RNA transfection with:

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H-(NS2)-J

|

H-(NS2)-J (mutation Y361H)

|

||||||

| Expt 1 | Expt 2 | Expt 3 | Expt 4 | Expt 5 | Expt 6 | Expt 7 | |

| E2 92 | N476D | ||||||

| p7 31 | Y777C | Y777C | |||||

| 41 | V783E | ||||||

| 45 | V787A | ||||||

| NS2 18 | M827V | ||||||

| 27 | K836R | ||||||

| 30 | I839T | I839Tb | I839S | ||||

| 38 | Q847R | ||||||

| 56 | N865G | N865D | |||||

| 62 | D871G | ||||||

| 80 | T889A | T889A | |||||

| 81 | K890R | K890R | |||||

| 98 | L907P | ||||||

| 119 | I928M | ||||||

| 120 | A929P | ||||||

| 136 | T945A | ||||||

Residues are numbered according to their positions within the original H77 sequence.

Mixed sequence with the wild type.

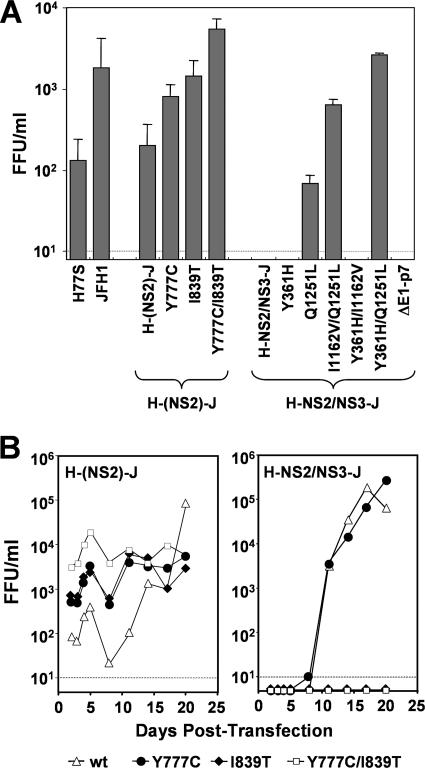

To learn whether these mutations specifically enhance virus production, we reintroduced them into their cognate chimeric cDNA, singly and in combination, and transfected the related RNAs into FT3-7 cells, as described above. Although transfection of the wild-type H-NS2/NS3-J RNA did not result in the release of infectious virus until 6 to 9 days after transfection (Fig. 1C), introduction of the Q1251L mutation into this construct resulted in an immediate release of infectious virus 2 days after transfection (Fig. 3A). This was not observed with the Y361H or the I1162V mutation. However, both of these mutations acted cooperatively with mutation Q1251L, with the Y361H/Q1251L double mutation resulting in the release of >103 FFU/ml of virus as early as 48 h after transfection. Although mutation Y361H by itself had no immediate effect on virus release by H-NS2/NS3-J, it did cause the release of detectable virus from transfected cells approximately 3 days earlier (day 8 versus day 11) than the unmodified chimeric RNA (data not shown). These results indicate that the efficient production of infectious virus from the H-NS2/NS3-J chimera requires an adaptive mutation within the NS3 sequence that most likely compensates for an incompatibility between the H77S and JFH1 RNA sequences that comprise it. Further characterization of the Q1251L mutation and its role in the production of vH-NS2/NS3-J will be reported elsewhere.

FIG. 3.

Compensatory mutations in the p7 and NS2 region of vH-(NS2)-J and the E1, NS2, and NS3 regions of vH-NS2/NS3-J enhance yields of infectious virus following RNA transfection. (A) Comparison of virus released by cells transfected with parental and chimeric HCV RNAs, with and without possible compensatory mutations. Results shown represent means of titers ± standard deviations of virus released into supernatant fluids on days 2 and 3 posttransfection. (B) Virus released into supernatant fluids of FT3-7 cell cultures following transfection with H-(NS2)-J (left panel) and H-NS2/NS3-J (right panel) RNAs without (▵) and with mutation Y777C (•) or I839T (♦) or both Y777C and I839T (□) mutations. No virus was detected in cultures of cells transfected with H-NS2/NS3-J RNAs containing the I839T mutation or both the I1839T and the Y777C mutations.

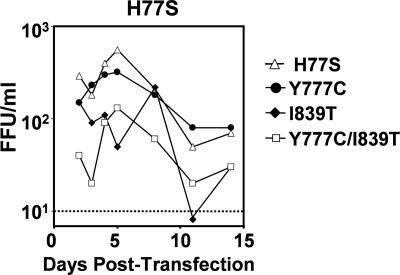

Similar experiments indicated that the Y777C (p7) and I839T (NS2) mutations increased the capacity of the H-(NS2)-J RNA chimera to produce infectious virus. Individually, these mutations caused average 10- and 13-fold increases, respectively, in vH-(NS2)-J yield over the first 8 days posttransfection (Fig. 3A and B, left panel). A combination of the two mutations resulted in an 80-fold increase in vH-(NS2)-J yield. Similar results were obtained in replicated experiments, including those in which RNAs were transfected into Huh-7.5 cells rather than FT3-7 cells as shown in Fig. 3 (data not shown). The effects of these mutations were specific to the H-(NS2)-J chimera, however, as neither mutation enhanced the release of infectious virus when inserted into H-NS2/NS3-J. In fact, mutation I839T abolished virus release by H-NS2/NS3-J, either when introduced alone or in combination with mutation Y777C (Fig. 3B, right panel). When placed into the parental H77S construct, mutation Y777C had no impact on infectious virus yield, while mutation I839T reduced but did not eliminate the production of infectious virus (Fig. 4). These results confirm that Y777C and I839T are compensatory mutations that act in a specific fashion to increase the yield of infectious virus from the H-(NS2)-J chimeric RNA. The locations of these mutations suggest that p7 and NS2 play key roles in the assembly and/or release of infectious virus and that interactions between p7 and the N-terminal NS2 domain (residues 746 to 947, derived from the genotype 1a H77S virus) and the C-terminal segment of NS2 (residues 951 to 1029 of JFH1) are essential for this process.

FIG. 4.

Compensatory mutations identified within p7 and NS2 of vH-(NS2)-J do not enhance yields of virus produced by transfected cells when placed into the background of the parental H77-S genomic RNA.

We determined the core NS2 sequences of viruses produced by cells transfected with the H-(NS2)-J chimera in six additional, independent experiments (Table 1). In three of these experiments, the transfected H-(NS2)-J RNA contained the Y361H mutation we identified within the E1 sequence of vH-NS2/NS3-J, because some experiments suggested it may minimally enhance the production of infectious virus by H-(NS2)-J (data not shown). The Y777C and I839T mutations were each independently identified in at least one of these additional transfection experiments, while other mutations that are compensatory for infectious virus production were found in both p7 (mutations V783E and, possibly, V787A) and NS2 (mutation I839S and others) (see Table 1; Fig. 5). Interestingly, the Y361H mutation (E1) appeared to act cooperatively with I839T and A929P (NS2) in promoting early virus release from transfected cells (Fig. 5). Silent mutations were also identified in some of these viral RNAs (data not shown); we did not characterize the phenotypic effects of these silent nucleotide substitutions, but they do not appear to be necessary for the efficient production of infectious chimeric virus (Fig. 3 and 5).

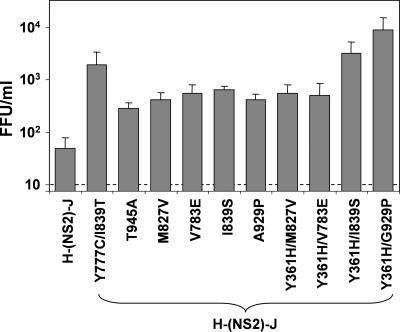

FIG. 5.

Other compensatory mutations identified within p7 or NS2 of vH-(NS2)-J or vH-(NS2)-H-Y361H (see Table 1) enhance yields of infectious virus released from transfected cells. Data shown are mean virus yields (FFU/ml means ± ranges) in cell culture fluids 2 days posttransfection of H-(NS2)-J RNA containing the indicated mutation, in two replicated experiments. See legend to Fig. 3A.

Mechanism of action of compensatory mutations in p7 and NS2.

If the compensatory mutations caused an increase in the efficiency of chimeric RNA replication, this could account for the enhanced release of infectious chimeric virus. However, this was not evident with either the Y777C or the I839T mutation when placed into the H-(NS2)-J background (either singly or together) and the resulting RNAs transfected into FT7-3 cells (Fig. 6A). Similarly, these mutations had no effect on the replication of H-NS2-J or the parental H77S RNA in Huh-7.5 cells (data not shown). It is also important to note that, while the I839T mutation abolished the release of chimeric virus when inserted into the H-NS2/NS3-J construct (Fig. 3B, right panel), it did not reduce the ability of this chimera's RNA to replicate (data not shown). Thus, these mutations do not control virus production by altering the efficiency of genome replication.

FIG. 6.

Semiquantitative RT-PCR assays for HCV RNA and GAPDH mRNA in lysates of FT3-7 cells following transfection of H-(NS2)-J RNA containing the indicated mutation. Dilution experiments demonstrated the ability of this semiquantitative RT-PCR assay to detect a twofold difference in HCV RNA abundance (data not shown).

A second possibility is that these compensatory mutations could correct incompatibilities in the sequences from the two genotypes that adversely affect processing of the polyprotein. However, these mutations had no consistent effect on the level of expression of fully processed NS3 protein expressed by cells transfected with the chimeric RNAs (Fig. 6B). Since the signal peptidase cleavage at the p7-NS2 junction and the cis cleavage at the NS2/3 junction in the chimera are known to be controlled by surrounding polypeptide sequences (3, 15), we also examined processing at these sites in chimeric polyprotein segments expressed in cell-free translation reactions in rabbit reticulocyte lysates (Fig. 7). We found no differences in the amount of mature NS2 produced from the chimeric versus the parental p7-NS4A or NS2-NS4a polyprotein segments in the presence of membranes nor any effects of either the Y777C or the I839T mutation on these processing events (see Fig. 7). Thus, the chimeric H-(NS2)-J polyprotein appears to be processed as efficiently as the parental H77S and JFH1 polyproteins. The data suggest that the compensatory mutations do not enhance virus yields by facilitating polyprotein expression or processing.

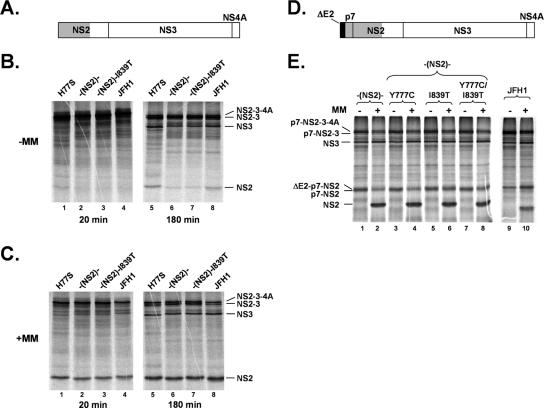

FIG. 7.

In vitro processing of parental H77S, JFH1, and chimeric HCV polyprotein segments produced by in vitro translation in rabbit reticulocyte lysate. (A to C) Processing of the NS2-NS3-NS4A (A) polyprotein segments of H77S, H-(NS2)-J, H-(NS2)-J/I839T, and JFH1, respectively, in the absence (B) or presence (C) of canine microsomal membranes (MM) for 20 or 180 min as indicated. There was less mature NS2 produced by the H-(NS2)-J segment (panel B, lane 6 versus lanes 5 and 8) (∼50% of that produced by H77S or JFH1 by Phosphoimager analysis), suggesting that the activity of the NS2/3 protease may be reduced in the chimera in the absence of membranes. However, this was not reversed by the I839T mutation in NS2 (panel B, lane 6 versus lane 7), and, moreover, there were no differences in the efficiencies of NS2-NS3 cleavage when the polyprotein segments were translated in the presence of microsomal membranes (panel C, lane 6 versus lanes 5 and 8). (D and E) Processing of the ΔE2-p7-NS2-NS3-NS4A segment (D) derived from H77S, JFH1, or H-(NS2)-J without or with mutation Y777C or I839T or both Y777C and I839T in the presence or absence (E) of microsomal membranes (MM) for 180 min.

Although H77S RNA produces far lower virus yields than JFH1, our previous studies indicate that cells transfected with H77S RNA release greater numbers of noninfectious particles of similar buoyant density (24). H77S particles have a lower specific infectivity (higher RNA copy no./FFU) and appear to initiate infection much less efficiently than JFH1 particles (24). Thus, we asked whether the compensatory mutations enhance the total number of particles released from RNA-transfected cells or, rather, increase the specific infectivity of released particles. We collected supernatant culture fluids 3 days posttransfection of H-(NS2)-J RNA, with or without the Y777C and I839T mutations, and isolated HCV particles by isopycnic ultracentrifugation through an iodixanol gradient. By quantitative RT-PCR, the greatest abundance of HCV-specific RNA was found to be present within fraction 6 (∼1.12 g/cm3) of each gradient (Fig. 8A). In contrast, peak infectivity was generally greatest in fraction 5 (∼1.08 g/cm3). These results are similar to those reported previously by Lindenbach et al. for a J6-JFH1 chimeric virus (10) and suggest that infectious particles represent a subset banding at a density slightly lower than that of most particles. Interestingly, while mutation Y777C or I839T had only a modest effect on the total number of RNA-containing particles in fraction 6 (Fig. 8A), these mutations, either alone or in combination, caused a greater increase in the less dense, infectious particles present in fraction 5 (Fig. 8A and B). This was associated with a substantial increase in the specific infectivity of particles in each fraction (Table 2). The data thus suggest that these mutations act singly and additively to specifically enhance the infectivity of particles released from RNA-transfected cells (especially those banding at a density of ∼1.08 g/cm3 or less) while having less of an impact on the numbers of RNA-containing particles released. The mutations had a striking positive effect on the specific infectivity of the less dense particles present within fractions 3 and 4 of these gradients (1.03 to 1.06 g/cm3) (Fig. 8B).

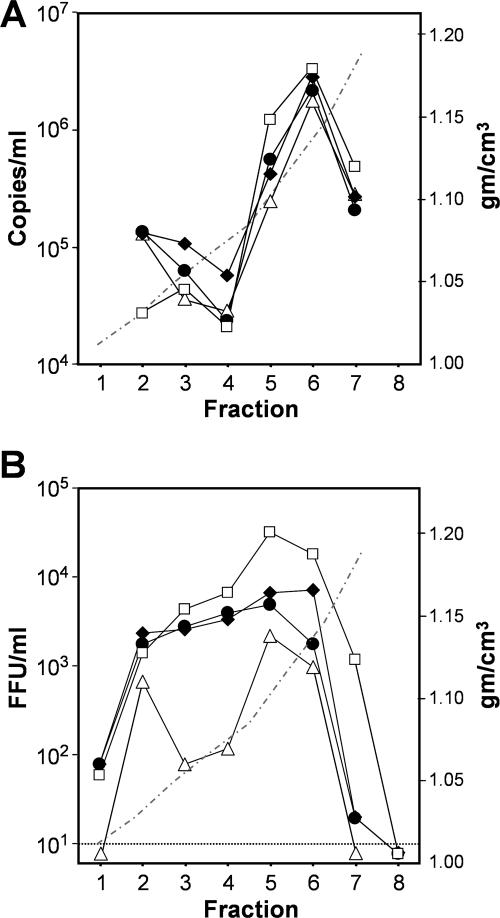

FIG. 8.

Equilibrium ultracentrifugation of H-(NS2)-J virus in iodixanol gradients (24). (A) TaqMan RT-PCR assays of HCV RNA in fractions of gradients loaded with concentrated cell culture supernatant fluids collected 3 days posttransfection with H-(NS2)-J (Δ) or H-(NS2)-J containing compensatory mutation Y777C (•), I839T (♦), or both Y777C and I839T (□). The dashed line indicates the density of fractions. (B) Infectious virus present within the gradient fractions shown in panel A.

TABLE 2.

Specific infectivity of vH-(NS2)-J in an iodixanol gradient

| Virus | RNA copies/FFU

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Fraction 5 | Fraction 6 | |

| v(NS2) | 110 | 1,700 |

| v(NS2) (Y777C) | 110 | 1,200 |

| v(NS2) (I839T) | 61 | 380 |

| v(NS2) (Y777C/I839T) | 38 | 180 |

DISCUSSION

The chimeric HCV isolates described here incorporate the structural proteins of genotype 1a virus into the background of the unique genotype 2a JFH1 strain. They should be useful in assessing the role of antibody in protecting against hepatitis C and in developing small molecule inhibitors that target viral entry. However, the various abilities of the chimeric genomes we constructed to direct the assembly and release of infectious virus particles and, in particular, the compensatory mutations that facilitate this process also offer rich and novel insights into these final steps of the viral life cycle.

Our strategy was to place sequences encoding the core p7 and part or all of the NS2 protein of H77S (a genotype 1a genome capable of very efficient RNA replication but only limited yields of infectious virus) into the background of JFH1 (a genotype 2a genome capable of both efficient RNA replication and infectious virus release) (19, 24). In one construct, H-(NS2)-J, we purposefully modeled a naturally occurring intergenotypic chimera in which genotype 2k and 1b sequences are fused within NS2 (7). Cells transfected with chimeric RNAs containing the H77S sequence encoding all or only the N-terminal 138 residues of NS2 released substantial titers of infectious virus into supernatant culture fluids (albeit, after variable delays), while a related chimera fused at the p7-NS2 junction failed to produce detectable infectious virus despite comparable RNA replication efficiency (Fig. 1). These latter results are different from those of Pietschmann et al. (16), who recently described the rescue of infectious virus from a similar JFH1 chimera encoding the core-E2 proteins of genotype 1b Con1 HCV. However, only a low level of virus was produced and it was not quantified.

It is interesting to note that the intracellular accumulation of core protein was notably greater 96 h after transfection of cells with the chimeric H-(NS2)-J RNA that produced infectious particles immediately after transfection than with the H-p7/NS2-J RNA that never produced infectious virus or the H-NS2/NS3-J RNA, which did not do so until days later (Fig. 2). These differences cannot be explained by differences in RNA replication (Fig. 1). They mirror the substantially greater accumulation of core protein that we noted previously in cells transfected with the parental JFH1 versus the H77S RNAs (24). Preliminary results of pulse-chase experiments suggest that this latter difference may be due to greater stability of the JFH1 protein (Y. Liang, M. Yi, and S. M. Lemon, unpublished observations). It is tempting to speculate from these data that the core may be stabilized by virtue of being packaged into nascent viral particles, but additional experiments will be needed to confirm this hypothesis.

Overall, our results suggest that the unique ability of JFH1 to produce high infectious virus yields is determined largely by sequences outside of the structural protein-coding region and is dependent upon genetic determinants within the nonstructural region (NS3-NS5B) and/or the 5′ and 3′ nontranslated RNA segments. However, our data also show that NS2 plays a critical role in this process. Unlike the other chimeras we studied, the H-p7/NS2-J chimeric RNA failed to produce detectable infectious virus, even after a lengthy period of RNA replication following transfection (Fig. 1). Since this chimera differs from H-(NS2)-J only in the N-terminal domain of NS2 [residues 810 to 947, which are from H77S in H-(NS2)-J], this suggests the need for homologous (same genotype) core-p7 and N-terminal NS2 sequences for efficient infectious particle release. This in turn suggests that the N-terminal domain of NS2 is likely to interact with one or more of the upstream structural proteins during virus assembly and/or release and that significant incompatibilities exist in the NS2 sequences of JFH1 and H77S that prevent efficient interactions of JFH1 NS2 with the H77 structural proteins. Strong genetic evidence to support this conclusion comes from our identification of compensatory mutations that facilitate the release of infectious virus particles from cells transfected with the chimeric RNAs. Since the cellular environment in which these chimeras replicate is constant, these compensatory mutations likely emerged because they correct incompatibilities between the proteins of these different HCV genotypes at sites of essential protein-protein interactions. The compensatory mutations we identified in the p7, NS2, and NS3 sequences of vH-NS2/NS3-J and vH-(NS2)-J were specific to each chimera (Fig. 2B, right panel, and data not shown). Since the C-terminal domain of NS2 (protease domain) is the only sequence that differs between them, the mutations most likely modulate essential interactions between it and NS3 (Q1251L) or between it and p7 and the N-terminal domain of NS2 (Y777C and I839T).

It is unlikely that these mutations act at the level of RNA, as each of the chimeric RNAs we constructed replicated efficiently in the absence of compensatory mutations (Fig. 1B and 6A). Moreover, we found no significant increases in RNA replication or viral protein expression when cells were transfected with the H-(NS2)-J chimera with or without the compensatory mutations (Fig. 6). Also, the I839T mutation ablated production of infectious virus from the H-NS2/NS3-J chimera (Fig. 3B, right panel) without adversely affecting its ability to replicate as RNA (data not shown). Neither p7 nor NS2 is known to have RNA-binding activity.

The analysis of vH-(NS2)-J viruses rescued from cells transfected with H-(NS2)-J RNA in replicated experiments led to the identification of multiple sets of mutations that enhance yields of infectious virus (Table 1; Fig. 3A and 5). These experiments confirmed the importance of mutations Y777C and I839T for vH-(NS2)-J production by repetitively and independently isolating both mutations. They also revealed a trend toward a combination of mutations within p7 and NS2 for increased yields of vH-(NS2)-J. Importantly, the compensatory vH-(NS2)-J mutations were localized to the p7 and N-terminal NS2 sequences derived from H77 (Fig. 9). As indicated above, these mutations were not required for the production of vH-NS2/NS3-J; indeed, mutation I839T ablated production of this chimeric virus (Fig. 3B, right panel). Thus, we suspect that they compensate for an incompatibility between the p7 amino-terminal NS2 H77 sequence (residues 746 to 947) and the C-terminal NS2 JFH1 sequence (residues 951 to 1029), which is unique to vH-(NS2)-J (Fig. 1). The fact that all of the vH-(NS2)-J compensatory mutations occurred within the H77 sequence and none within the JFH1 NS2 sequence is of particular interest. Possibly this reflects other constraints on the carboxyl-terminal NS2 domain. For similar reasons, the Q1251L mutation in v(NS2/NS3) suggests this C-terminal domain of NS2 may interact with NS3 in a genotype-specific fashion. Other evidence has been presented recently for an interaction between these proteins (9). The production of infectious pestivirus particles has also been shown to be dependent upon uncleaved NS2-NS3, indicating that NS3 contributes to assembly in this flavivirus genus (1).

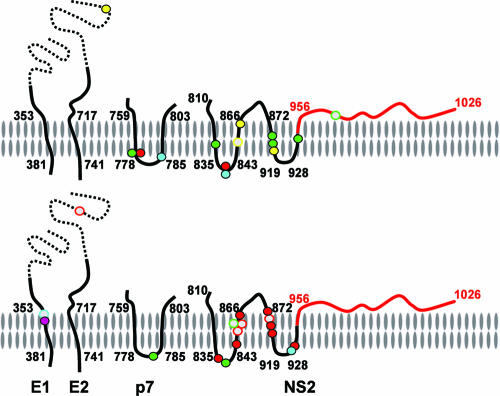

FIG. 9.

Compensatory mutations identified in vH-(NS2)-J (top) or vH-(NS2)-J/Y361H (bottom) are located primarily within the transmembrane domains of E1, p7, and NS2. In each image, the membrane is oriented with the cytosolic side down and the luminal side of the membrane upwards. The viral polyprotein backbone is represented by the continuous line, with the H77S sequence in black (the ectodomains of the envelope proteins are shown as dashed lines) and the JFH1 sequence in red. Membrane topologies of these proteins are those predicted by Patargias et al. (13) for p7 and Yamaga et al. (21) for NS2. Alternatively, the C-terminal protease domain of NS2 may be located on the cytosolic side of the membrane (12). Solid symbols represent mutations that alter the protein sequence and are color coded according to the transfection experiment in which they were identified (see Table 1); open symbols represent silent mutations.

The vH-(NS2)-J compensatory mutations are for the most part within or immediately adjacent to the putative transmembrane domains of p7 or NS2 (Fig. 9) (13, 21). Within NS2, these mutations are largely upstream of the NS2 protease domain (NS2pro), which recent structural studies suggests forms a dimeric cysteine protease with dual composite active sites (12). Three mutations that we identified in infectious vH-(NS2)-J (I928M, A929P, and T945A) are at residues included in the NS2pro domain polypeptide that was crystallized in this recent work. These mutations flank the H2 helix of NS2pro which is proposed to be inserted into the lipid bilayer (12). The location of the vH-(NS2)-J compensatory mutations within and proximate to points of membrane insertion of p7 and NS2 suggests that they may facilitate intramembranous interactions between these proteins that are important for the assembly and release of infectious particles.

However, our data suggest that these mutations in p7 and NS2 do not have a dramatic effect on the overall numbers of RNA-containing vH-(NS2)-J particles released from the cell. Compared with the unmodified H-(NS2)-J chimera, cells transfected with RNA containing the compensatory Y777C and/or I839T mutation released only marginally greater numbers of the most abundant RNA-containing particles which have a buoyant density of ∼1.13 g/cm3 (Fig. 8A, fraction 6). In contrast, these mutations substantially increased the specific infectivity of these as well as the lighter particles that were released into the supernatant fluids (Table 2; Fig. 8B). p7 has been suggested to assemble into a multimeric ion channel (5, 6, 14). Since studies with closely related pestiviruses suggest that this small protein is not incorporated into the virion (4), its function may be to protect the infectivity of newly assembled HCV particles during the process of virus release. The protein-protein interactions we postulate could be important for anchoring p7 to NS2 within the membrane, potentially enhancing the ability of the p7 to protect newly assembled particles. This hypothesis, while speculative, is consistent with the ability of the compensatory mutations to enhance the specific infectivity of particles released by the cell (Fig. 8; Table 2), and should provide interesting directions for future research efforts.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Annette Martin for critical reading of the manuscript, Francis Bodola and Rodrigo Villanueva for expert technical assistance, Masaru Enomoto and Kui Li for FT3-7 cells, Takaji Wakita for JFH1 cDNA, and Charles Rice for Huh-7.5 cells.

This work was supported in part by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grants U19-AI40035, R21-AI063451, and N01-AI25488.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 1 November 2006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agapov, E. V., C. L. Murray, I. Frolov, L. Qu, T. M. Myers, and C. M. Rice. 2004. Uncleaved NS2-3 is required for production of infectious bovine viral diarrhea virus. J. Virol. 78:2414-2425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blight, K. J., J. A. McKeating, and C. M. Rice. 2002. Highly permissive cell lines for subgenomic and genomic hepatitis C virus RNA replication. J. Virol. 76:13001-13014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carrere-Kremer, S., C. Montpellier, L. Lorenzo, B. Brulin, L. Cocquerel, S. Belouzard, F. Penin, and J. Dubuisson. 2004. Regulation of hepatitis C virus polyprotein processing by signal peptidase involves structural determinants at the p7 sequence junctions. J. Biol. Chem. 279:41384-41392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elbers, K., N. Tautz, P. Becher, D. Stoll, T. Rümenapf, and H.-J. Thiel. 1996. Processing in the pestivirus E2-NS2 region: identification of proteins p7 and E2p7. J. Virol. 70:4131-4135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Griffin, S., D. Clarke, C. McCormick, D. Rowlands, and M. Harris. 2005. Signal peptide cleavage and internal targeting signals direct the hepatitis C virus p7 protein to distinct intracellular membranes. J. Virol. 79:15525-15536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Griffin, S. D., L. P. Beales, D. S. Clarke, O. Worsfold, S. D. Evans, J. Jaeger, M. P. Harris, and D. J. Rowlands. 2003. The p7 protein of hepatitis C virus forms an ion channel that is blocked by the antiviral drug, amantadine. FEBS Lett. 535:34-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kalinina, O., H. Norder, S. Mukomolov, and L. O. Magnius. 2002. A natural intergenotypic recombinant of hepatitis C virus identified in St. Petersburg. J. Virol. 76:4034-4043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kato, T., T. Date, M. Miyamoto, A. Furusaka, K. Tokushige, M. Mizokami, and T. Wakita. 2003. Efficient replication of the genotype 2a hepatitis C virus subgenomic replicon. Gastroenterology 125:1808-1817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kiiver, K., A. Merits, M. Ustav, and E. Zusinaite. 2006. Complex formation between hepatitis C virus NS2 and NS3 proteins. Virus Res. 117:264-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lindenbach, B. D., M. J. Evans, A. J. Syder, B. Wolk, T. L. Tellinghuisen, C. C. Liu, T. Maruyama, R. O. Hynes, D. R. Burton, J. A. McKeating, and C. M. Rice. 2005. Complete replication of hepatitis C virus in cell culture. Science 309:623-626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lohmann, V., F. Korner, J. Koch, U. Herian, L. Theilmann, and R. Bartenschlager. 1999. Replication of subgenomic hepatitis C virus RNAs in a hepatoma cell line. Science 285:110-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lorenz, I. C., J. Marcotrigiano, T. G. Dentzer, and C. M. Rice. 2006. Structure of the catalytic domain of the hepatitis C virus NS2-3 protease. Nature 442:831-835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patargias, G., N. Zitzmann, R. Dwek, and W. B. Fischer. 2006. Protein-protein interactions: modeling the hepatitis C virus ion channel p7. J. Med. Chem. 49:648-655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pavlovic, D., D. C. Neville, O. Argaud, B. Blumberg, R. A. Dwek, W. B. Fischer, and N. Zitzmann. 2003. The hepatitis C virus p7 protein forms an ion channel that is inhibited by long-alkyl-chain iminosugar derivatives. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:6104-6108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pieroni, L., E. Santolini, C. Fipaldini, L. Pacini, G. Migliaccio, and N. La Monica. 1997. In vitro study of the NS2-3 protease of hepatitis C virus. J. Virol. 71:6373-6380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pietschmann, T., A. Kaul, G. Koutsoudakis, A. Shavinskaya, S. Kallis, E. Steinmann, K. Abid, F. Negro, M. Dreux, F. L. Cosset, and R. Bartenschlager. 2006. Construction and characterization of infectious intragenotypic and intergenotypic hepatitis C virus chimeras. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:7408-7413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shepard, C. W., L. Finelli, and M. J. Alter. 2005. Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection. Lancet 5:558-567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sumpter, R., Jr., M.-Y. Loo, E. Foy, K. Li, M. Yoneyama, T. Fujita, S. M. Lemon, and M. Gale, Jr. 2005. Regulating intracellular antiviral defense and permissiveness to hepatitis C virus RNA replication through a cellular RNA helicase, RIG-I. J. Virol. 79:2689-2699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wakita, T., T. Pietschmann, T. Kato, T. Date, M. Miyamoto, Z. Zhao, K. Murthy, A. Habermann, H.-G. Krauslich, M. Mizokami, R. Bartenschlager, and T. J. Liang. 2005. Production of infectious hepatitis C virus in tissue culture from a cloned viral genome. Nat. Med. 11:791-796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Welbourn, S., R. Green, I. Gamache, S. Dandache, V. Lohmann, R. Bartenschlager, K. Meerovitch, and A. Pause. 2005. Hepatitis C virus NS2/3 processing is required for NS3 stability and viral RNA replication. J. Biol. Chem. 280:29604-29611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamaga, A. K., and J. H. Ou. 2002. Membrane topology of the hepatitis C virus NS2 protein. J. Biol. Chem. 277:33228-33234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yi, M., and S. M. Lemon. 2003. 3′ nontranslated RNA signals required for replication of hepatitis C virus RNA. J. Virol. 77:3557-3568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yi, M., and S. M. Lemon. 2004. Adaptive mutations producing efficient replication of genotype 1a hepatitis C virus RNA in normal Huh7 cells. J. Virol. 78:7904-7915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yi, M., R. A. Villanueva, D. L. Thomas, T. Wakita, and S. M. Lemon. 2006. Production of infectious genotype 1a hepatitis C virus (Hutchinson strain) in cultured human hepatoma cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:2310-2315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhong, J., P. Gastaminza, G. Cheng, S. Kapadia, T. Kato, D. R. Burton, S. F. Wieland, S. L. Uprichard, T. Wakita, and F. V. Chisari. 2005. Robust hepatitis C virus infection in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:9294-9299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]