Abstract

Reoviruses induce apoptosis both in cultured cells and in vivo. Apoptosis plays a major role in the pathogenesis of reovirus encephalitis and myocarditis in infected mice. Reovirus-induced apoptosis is dependent on the activation of transcription factor NF-κB and downstream cellular genes. To better understand the mechanism of NF-κB activation by reovirus, NF-κB signaling intermediates under reovirus control were investigated at the level of Rel, IκB, and IκB kinase (IKK) proteins. We found that reovirus infection leads initially to nuclear translocation of p50 and RelA, followed by delayed mobilization of c-Rel and p52. This biphasic pattern of Rel protein activation is associated with the degradation of the NF-κB inhibitor IκBα but not the structurally related inhibitors IκBβ or IκBɛ. Using IKK subunit-specific small interfering RNAs and cells deficient in individual IKK subunits, we demonstrate that IKKα but not IKKβ is required for reovirus-induced NF-κB activation and apoptosis. Despite the preferential usage of IKKα, both NF-κB activation and apoptosis were attenuated in cells lacking IKKγ/Nemo, an essential regulatory subunit of IKKβ. Moreover, deletion of the gene encoding NF-κB-inducing kinase, which is known to modulate IKKα function, had no inhibitory effect on either response in reovirus-infected cells. Collectively, these findings indicate a novel pathway of NF-κB/Rel activation involving IKKα and IKKγ/Nemo, which together mediate the expression of downstream proapoptotic genes in reovirus-infected cells.

Mammalian reoviruses are nonenveloped viruses that contain a genome of 10 segments of double-stranded RNA (52). Following infection of newborn mice, reovirus disseminates systemically, causing injury to the central nervous system (CNS), heart, and liver (76). Apoptosis induced by reovirus appears to be the primary mechanism for virus-induced encephalitis (53, 54, 59) and myocarditis (22, 23, 54). Disassembly of internalized virus in the endocytic pathway provides the initial viral trigger for stimulating the signaling pathways that elicit an apoptotic response (19, 21).

Transcription factor NF-κB plays an important regulatory role in apoptosis evoked by reovirus in cultured cells (20) and in vivo (54). Inducible members of the NF-κB family are sequestered in the cytoplasm by inhibitory IκB proteins, including IκBα, IκBβ, IκBɛ, and p100/NF-κB2 (3, 31, 68, 79, 82). In response to a wide variety of NF-κB inducers, IκB proteins are phosphorylated at specific serine residues, earmarking these molecules for destruction by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway (7, 12, 31, 56, 75, 82). Phosphorylation of IκB proteins is mediated by cytokine-inducible IκB kinases (IKKs) IKKα and IKKβ (47, 78), which can form higher-order complexes containing a regulatory subunit called IKKγ/Nemo (26, 50, 62, 88, 91). A primary function of IKKβ is to modulate the inhibitory interaction of IκBα with the prototypical form of NF-κB containing p50/RelA dimers (25, 26, 50, 58, 69). This regulatory circuit, termed the classical pathway of NF-κB activation, is strictly dependent on the presence of IKKγ/Nemo (64, 65, 88). In contrast, IKKα functions in an alternative IKKγ-independent pathway of NF-κB activation that leads to the proteolytic processing of p100 and the production of a functional p52 Rel subunit (16, 66, 71). Unlike the classical IKKβ-directed pathway of NF-κB activation, the alternative pathway involving IKKα is dependent on its prior phosphorylation by NF-κB-inducing kinase (NIK) (43, 66, 85). In addition to the cytoplasmic function of IKKα, a nuclear role for IKKα in the transcriptional activation of NF-κB-responsive genes has been suggested by in vitro studies (1, 32, 33, 41, 48, 69, 87).

To better understand the mechanism of NF-κB activation by reovirus, we conducted experiments to define the NF-κB/Rel, IκB, and IKK proteins that are under reovirus control. These studies revealed that NF-κB/Rel proteins are mobilized to the nuclear compartment with biphasic kinetics following reovirus infection. Reovirus-induced activation of NF-κB/Rel proteins is accompanied by selective degradation of IκBα, suggesting a role for IKKβ. However, additional studies with IKK-specific small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) and IKK-deficient cells clearly demonstrate that IKKα rather than IKKβ plays an essential role in the mechanism by which reovirus activates NF-κB and downstream apoptotic genes. We also assembled evidence indicating that the reovirus/IKKα axis is intact in cells lacking NIK, an upstream activator of IKKα, but not in cells lacking the IKKβ regulatory subunit IKKγ/Nemo. Taken together, these data suggest that reovirus activates the IKKα pathway of the NF-κB signaling apparatus downstream of NIK, perhaps via direct interactions with the regulatory subunit IKKγ/Nemo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells, viruses, and reagents.

HeLa cells, 293T cells, and murine embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) were maintained in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U/ml of penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 25 ng/ml of amphotericin B (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). MEFs deficient in IKKα (34), IKKβ (42), IKKγ/Nemo (46), and NIK (89) have been described previously. HeLa cells stably expressing IKK subunit-specific short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) were generated by stable transduction with amphotyped Moloney murine retroviruses produced in Phoenix A packaging cells provided by Garry Nolan (Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA) (K. B. Marcu, unpublished data). The retroviral vectors were engineered to coexpress green fluorescent protein (GFP) and blasticidin-resistance genes with or without shRNAs specific for human IKKα or IKKβ inserted into Mir-30 cassettes linked to GFP (55).

Reovirus type 3 Dearing (T3D) is a laboratory stock. Purified reovirus virions were generated by using second- or third-passage L-cell lysate stocks of twice-plaque-purified reovirus as described previously (27). Viral particles were Freon extracted from infected cell lysates, layered onto 1.2- to 1.4-g/cm3 CsCl gradients, and centrifuged at 62,000 × g for 18 h. Bands corresponding to virions (1.36 g/cm3) were collected and dialyzed in virion storage buffer (150 mM NaCl, 15 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4]). Concentrations of reovirus virions in purified preparations were determined from an equivalence of one optical density unit at 260 nm equaling 2.1 × 1012 virions (70). Viral titer was determined by plaque assay using L cells (80). Particle-to-PFU ratios of these preparations varied from 10:1 to 100:1.

Antisera specific for IκBα, IκBβ, IκBɛ, p50, p65/RelA, RelB, c-Rel, IKKγ/Nemo, and β-actin were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Antiserum specific for p100/p52 was purchased from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY). The agonistic lymphotoxin-β receptor antiserum was purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). A low-molecular-weight IKK inhibitor, Compound A (92), was obtained from Karl Ziegelbauer (Bayer Health Care AG, Leverkusen, Germany).

EMSA.

Cells (3 × 106) grown in 100-mm tissue-culture dishes (Costar, Cambridge, MA) were treated with 20 ng/ml of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), adsorbed with T3D at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 100 PFU/cell, or treated with gel saline (mock infection). After incubation at 37°C for various intervals, nuclear extracts (10 μg total protein) were assayed for NF-κB activation by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) using a 32P-labeled oligonucleotide consisting of the NF-κB consensus-binding sequence (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) as described previously (20). For supershift assays, 2 μg of rabbit polyclonal antiserum specific for p50, p52, RelA, RelB, or c-Rel was added to the binding reaction mixtures and incubated at 4°C for 30 min prior to the addition of radiolabeled oligonucleotide. Nucleoprotein complexes were subjected to electrophoresis in native 5% polyacrylamide gels at 180 V for 90 min, dried in a vacuum, and exposed to Biomax MR film (Kodak, Rochester, NY). Band intensity was quantified by determining photostimulus luminescence (PSL) units using a Fuji2000 phosphorimager and Multi Gauge software (Fuji Medical Systems, Inc., Stamford, CT).

Immunoblot assay.

Cells (8 × 105) were treated with 20 ng/ml of TNF-α, adsorbed with T3D at an MOI of 100 PFU/cell, or mock infected. Whole-cell extracts were generated by incubation with lysis buffer (10 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 10 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM EGTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.1% Igepal, 1 mM Na4O7P2, 1 mM NaF, 1 mM NaVO3, 1 μM microcystin). Extracts (10 to 50 μg total protein) were resolved by electrophoresis in 10% polyacrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blocked at 4°C overnight in blocking buffer (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS] containing 0.1% Tween 20 and 5% bovine serum albumin). Immunoblots were performed by incubating membranes with primary antibodies diluted 1:500 to 1:2,000 in blocking buffer at room temperature for 1 h. Membranes were washed three times for 10 min each with washing buffer (PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20) and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) and bovine anti-goat antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) diluted 1:2,000 and 1:3,000, respectively. After three washes, membranes were incubated for 1 min with chemiluminescent peroxidase substrate (Amersham Biosciences) and exposed to film. Band intensity was quantified by using the Image J program (NIH, Bethesda, MD).

Kinase assay.

Cells (8 × 105) were treated with 20 ng/ml of TNF-α, adsorbed with T3D at an MOI of 100 PFU/cell, or mock infected. Whole-cell extracts were incubated with an IKKγ-specific antiserum in the presence of ELB buffer (50 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 250 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 0.1% Igepal). Immunoprecipitates were equilibrated in kinase buffer (10 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM MnCl2, 12.5 mM β-glycerophosphate, 50 μM Na3VO4, 2 mM NaF) and incubated with 10 μM ATP, 5 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP (PerkinElmer), and 1 μg of recombinant glutathione S-transferase (GST) protein fused to amino acids 1 to 54 of IκBα (GST-IκBα) at 30°C for 30 min (13). Kinase reactions were terminated by heat denaturation in the presence of 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS). Radiolabeled products were resolved by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and visualized by autoradiography.

RNA interference and NF-κB reporter assays.

293T cells (105) grown in 24-well tissue-culture plates (Costar) were transfected with plasmids encoding shRNAs specific for IKKα, IKKβ, or IKKγ/Nemo or a negative-control shRNA (Millipore Corp., Billerica, MA) using FuGENE 6 transfection reagent (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were incubated at 37°C for 48 h before a second transfection with plasmids encoding the appropriate shRNA along with 0.15 μg/well of NF-κB-reporter plasmid pNF-κB-Luc, which expresses firefly luciferase under NF-κB control (9), and 0.05 μg/well of pRenilla-Luc, which expresses Renilla luciferase constitutively (9), by using FuGENE 6. After an additional 24 h of incubation at 37°C, cells were treated with 10 ng/ml of TNF-α, adsorbed with T3D at an MOI of 100 PFU/cell, or mock infected. Luciferase activity was assessed by using a Dual-Luciferase assay kit (Promega Corp., Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Caspase 3/7 activity assay.

Cells (3 × 103) grown in clear-bottom, black-walled, 96-well tissue culture plates (Costar) were inoculated with 10 ng/ml of TNF-α, a combination of 10 ng/ml of TNF-α and 10 μg/ml of cycloheximide (Sigma-Aldrich), or T3D at an MOI of 1,000 PFU/cell or were mock infected. Following incubation at 37°C for either 12 (TNF-α) or 24 (T3D) h, caspase 3/7 activity was quantified by using a Caspase-Glo 3/7 assay (Promega). Luminescence was detected by using a Topcount NXT luminometer (Packard Biosciences Co., Meriden, CT). The treatment of cells with cycloheximide blocks protein synthesis and enhances apoptosis induced by TNF-α (83).

Trypan blue exclusion assay.

Cells (4 × 104) grown in six-well tissue culture plates were inoculated with 10 ng/ml of TNF-α, a combination of 10 ng/ml of TNF-α and 10 μg/ml of cycloheximide, or T3D at an MOI of 1,000 PFU/cell or were mock infected. Following incubation at 37°C for either 12 (TNF-α) or 24 (T3D) h, cells were collected and washed with PBS. The cell pellet was resuspended in 50 μl of PBS and stained using 100 μl of a solution containing 0.4% trypan blue (Kodak) in PBS. For each experiment, 200 to 300 cells were counted, and the percentage of cell death was determined by light microscopy (Axiovert 200; Zeiss, Oberköchen, Germany).

Statistical analysis.

Mean values obtained by EMSAs, immunoblotting, and apoptosis assays were compared by using unpaired Student's t test as applied with Microsoft Excel software (Microsoft, Redmond, WA). P values of less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Reovirus infection results in the biphasic activation of NF-κB/Rel DNA-binding proteins.

In prior studies, we found that reovirus activates the functional expression of p50/RelA complexes, suggesting the involvement of classical NF-κB signaling (20). However, it remained unclear whether NF-κB/Rel proteins linked to the alternative pathway of the NF-κB pathway are activated during reovirus infection. To more completely define the composition of NF-κB complexes activated by reovirus, we used nuclear extracts from reovirus-infected HeLa cells and Rel-specific antibodies to monitor the composition of DNA-binding complexes formed in EMSAs. NF-κB/Rel DNA-binding activity was readily detected over background levels (mock treatment) within 2 h after infection with reovirus strain T3D (Fig. 1A), which potently induces apoptosis in cultured cells (20, 60, 77) and the murine CNS (53). Peak levels of NF-κB/Rel DNA-binding activity were observed at 4 to 8 h postinfection. Supershift analysis of extracts obtained at 4, 6, and 8 h postinfection revealed the presence of DNA/protein complexes containing p50 and RelA but neither p52 nor RelB (Fig. 1B), suggesting preferential usage of the classical versus alternative NF-κB pathway by reovirus. Complexes containing c-Rel were apparent in supershift assays only after 8 h of infection (Fig. 1B). Thus, reovirus induces a biphasic pattern of NF-κB/Rel activation featuring the initial nuclear translocation of complexes consisting of p50 and RelA, followed by those containing p50, RelA, and c-Rel. Given that the cellular gene encoding c-Rel contains functional NF-κB-binding sites (29), this expression pattern may reflect de novo synthesis of c-Rel rather than its mobilization from a latent cytoplasmic pool.

FIG. 1.

Biphasic activation of NF-κB/Rel proteins in reovirus-infected cells. (A) Nuclear extracts were prepared from uninfected HeLa cells (0 h), mock-infected cells (Mock), or cells infected with T3D at an MOI of 100 PFU/cell for the times shown. Cells also were treated with 20 ng/ml of TNF-α for 30 min as a positive control. Extracts were incubated with a radiolabeled NF-κB consensus oligonucleotide, and the resulting protein-oligonucleotide complexes were resolved by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, dried, and exposed to film. (B) Nuclear extracts prepared at 4, 6, and 8 h postinfection were incubated with antisera specific for p50, p52, RelA, RelB, or c-Rel prior to the addition of a radiolabeled NF-κB consensus oligonucleotide. NF-κB-containing complexes are indicated.

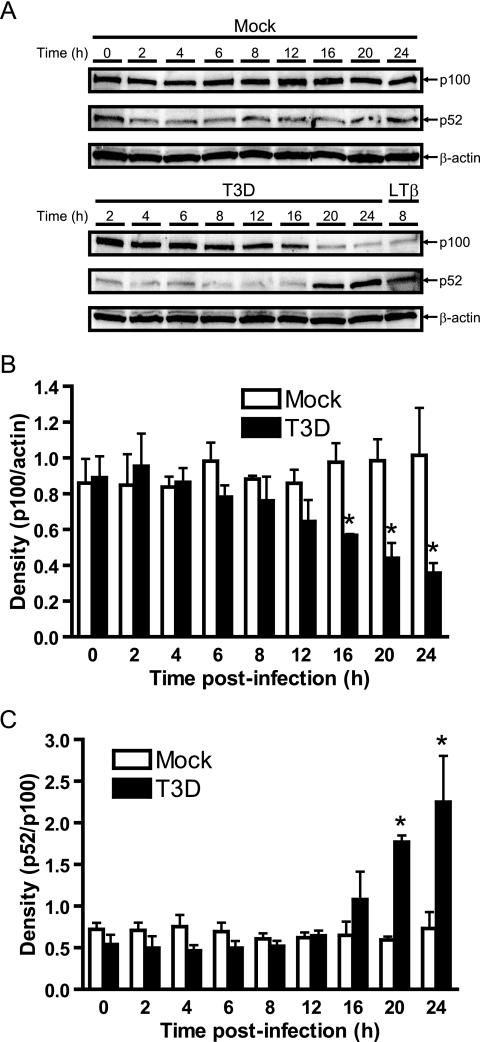

These initial experiments conducted over an 8-h time course provided no evidence for the capacity of reovirus to stimulate the nuclear expression of p52, a signature Rel protein involved in the alternative pathway of NF-κB signaling. To further investigate whether reovirus interfaces with the alternative NF-κB pathway, we extended the time course of T3D infection to 24 h and monitored extracts for the processing of p100 to p52 (66). Levels of p100 were significantly reduced between 16 and 24 h postinfection (Fig. 2). Consistent with a precursor/product relationship, diminution of p100 protein levels was accompanied by a significant increase in the steady-state levels of p52 (Fig. 2A and C). RelB nuclear localization also was observed approximately 16 to 24 h following reovirus infection (data not shown). Taken together with the NF-κB/Rel profiling data shown in Fig. 1B, these findings suggest that reovirus engages not only the classical pathway of NF-κB signaling but also the alternative pathway, albeit at much later times of infection.

FIG. 2.

Processing of p100 to p52 during reovirus infection. (A) Whole-cell extracts were prepared from uninfected HeLa cells (0 h), mock-infected cells (Mock), or cells infected with reovirus T3D at an MOI of 100 PFU/cell for the times shown. Cells also were treated with 2 μg/ml of an agonistic lymphotoxin-β receptor antiserum for 8 h as a positive control. Extracts were resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and immunoblotted by using an antiserum specific for p100/p52. Band intensity was quantified by using the Image J program. The results are expressed as the mean ratio of (B) p100/actin or (C) p52/p100 for three independent experiments. Error bars indicate standard deviations. *, P < 0.05 as determined by Student's t test in comparison to untreated cells (0 h).

Reovirus infection leads to the selective degradation of IκBα.

Activation of the classical NF-κB pathway by physiologic agonists is dependent primarily on the degradation of IκBα (reviewed in references 4, 28, and 30), an inhibitor that sequesters p50/RelA complexes in the cytoplasmic compartment (3). We have shown that degradation-resistant forms of IκBα attenuate reovirus-induced apoptosis, which is critically dependent on NF-κB activation (20). However, mammalian cells express other labile inhibitors that are structurally similar to IκBα, such as IκBβ (44) and IκBɛ (82). Indeed, prior studies suggest a potential role for signal-dependent degradation of IκBβ (74) and IκBɛ (82) in the inducible nuclear entry of c-Rel. To determine whether any of these inhibitors is under reovirus control, we monitored their levels in T3D-infected cells in immunoblot studies using IκB-specific antibodies. The cellular pool of IκBα was significantly reduced within 4 h after infection with T3D (Fig. 3A and B). In contrast, levels of IκBβ and IκBɛ were maintained under the same stimulatory conditions over the entire 8-h time course (Fig. 2C to F). We conclude that IκBα is a primary cellular target of reovirus, which is fully consistent with its capacity to stimulate nuclear translocation of NF-κB p50/RelA.

FIG. 3.

Reovirus infection leads to degradation of IκBα but not IκBβ or IκBɛ. Cytoplasmic extracts were prepared from uninfected HeLa cells (0 h), mock-infected cells (Mock), or cells infected with reovirus T3D at an MOI of 100 PFU/cell for the times shown. Cells also were treated with 20 ng/ml of TNF-α for 10 min as a positive control. Extracts were resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and immunoblotted by using antisera specific for (A) IκBα, (C) IκBβ, or (E) IκBɛ. An actin-specific antiserum was used to detect levels of actin as a loading control. Band intensity corresponding to levels of (B) IκBα, (D) IκBβ, and (F) IκBɛ was quantified by using the Image J program. The results are expressed as the mean ratio of IκB/actin for three independent experiments. Error bars indicate standard deviations. *, P < 0.05 as determined by Student's t test in comparison to untreated cells (0 h).

IKKα and IKKγ/Nemo are required for reovirus-induced NF-κB activation.

We next investigated the mechanism by which reovirus destabilizes IκB proteins. Cytokine-induced degradation of NF-κB inhibitors is dependent on their phosphorylation at specific serine residues by IKKs such as IKKα and IKKβ (7, 26, 91). These structurally related enzymes can interact and form higher-order complexes with other cellular proteins (reviewed in references 28 and 30). Integration of the regulatory protein IKKγ/Nemo into such complexes is required for the activation of IKKβ (64, 65, 88) but not IKKα (16, 24, 66). The best-characterized substrate of IKKβ is IκBα (35, 50), whereas IKKα catalyzes phosphorylation of p100/NF-κB2 (66, 85).

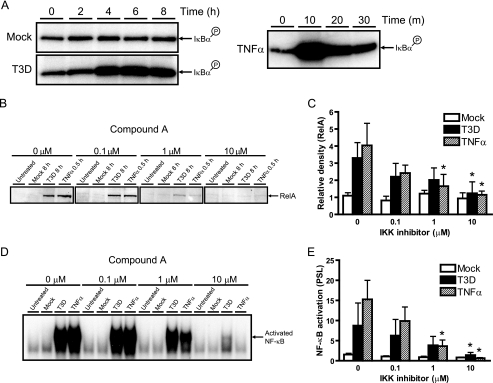

To determine whether either IKKα or IKKβ is required for the reovirus-induced activation of NF-κB, cellular IKK complexes were immunopurified from HeLa cells either before or after infection with T3D and monitored for the capacity to phosphorylate IκBα in vitro. In keeping with the kinetics of IκBα degradation (Fig. 3A) and NF-κB activation (Fig. 1A), IκB kinase activity exceeding basal levels in uninfected cells was readily detected within 4 h after exposure to T3D and sustained for at least an additional 4 h (Fig. 4A). These data suggest that IKKs are critically involved in the mechanism by which reovirus diminishes the cellular pool of IκBα (Fig. 3A).

FIG. 4.

Involvement of IKKs in reovirus-induced NF-κB activation. (A) Whole-cell extracts were prepared from uninfected HeLa cells (0 h), mock-infected cells (Mock), or cells infected with reovirus T3D at an MOI of 100 PFU/cell for the times shown. Cells also were treated with 20 ng/ml of TNF-α for the times shown as a positive control. The IKK complex was immunoprecipitated by using an IKKγ-specific antiserum prior to incubation with a GST-IκBα substrate in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP. Kinase reactions were resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and visualized by autoradiography. (B) HeLa cells were pretreated with IKK inhibitor Compound A for 1 h at the concentrations shown and then uninfected (Untreated), mock infected (Mock), or infected with reovirus T3D at an MOI of 100 PFU/cell for the times shown. Nuclear extracts were resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and immunoblotted by using a RelA-specific antiserum. (C) Band intensity was quantified relative to uninfected cells by using the Image J program. The results are expressed as the mean RelA band intensity for three independent experiments. Error bars indicate standard deviations. *, P < 0.05 as determined by Student's t test in comparison to untreated cells (0 μM). (D) Nuclear extracts from the experiment shown in panel B were incubated with a radiolabeled NF-κB consensus oligonucleotide, and the resulting protein-oligonucleotide complexes were resolved by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, dried, and exposed to film. (E) Band intensity was quantified by determining PSL units relative to uninfected cells for four independent experiments. Error bars indicate standard deviations. *, P < 0.05 as determined by Student's t test in comparison to untreated cells (0 μM).

To determine whether IKK activation is required for the nuclear translocation of NF-κB by reovirus, cells were treated with escalating doses of Compound A, a low-molecular-weight inhibitor of IKK (92), prior to infection with T3D. Importantly, Compound A inhibits IKKβ more efficiently than IKKα (92). As demonstrated by immunoblots measuring p65/RelA nuclear localization, treatment of cells with Compound A suppressed NF-κB trafficking induced by reovirus (Fig. 4B and C). Concordantly, EMSAs performed with nuclear extracts from the same panel of infected cells indicated that Compound A had a marked inhibitory effect on reovirus-induced NF-κB DNA-binding activity (Fig. 4D and E), although this inhibition was incomplete, perhaps reflecting residual IKKα activity. These pharmacological data suggest that reovirus activates NF-κB via a mechanism involving IKKα, IKKβ, or both of these IKKs.

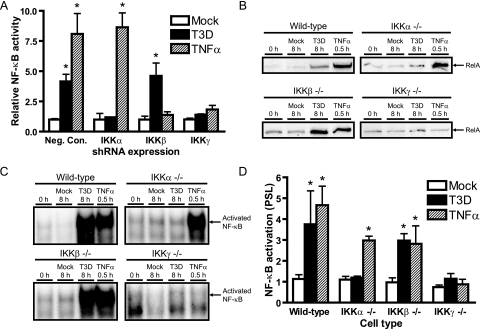

To identify the IKK subunits responsible for NF-κB activation by reovirus, NF-κB-dependent gene expression was assessed by using 293T cells transiently transfected with shRNA-encoding plasmids engineered to diminish expression of IKKα, IKKβ, or the IKKβ regulatory subunit IKKγ/Nemo (Fig. 5A). NF-κB reporter gene activity was dramatically reduced in cells expressing shRNA specific for either IKKα or IKKγ/Nemo in comparison to cells expressing IKKβ-specific shRNA or negative control shRNA, suggesting that IKKα and IKKγ/Nemo are required for reovirus-induced NF-κB activation. To confirm a requirement for IKKα and IKKγ/Nemo in the activation of NF-κB in response to reovirus, RelA nuclear localization was assessed with MEFs deficient in IKKα, IKKβ, or IKKγ/Nemo. Nuclear extracts from wild-type and IKK-deficient MEFs were probed by immunoblotting for RelA following infection with T3D for 8 h, which corresponds to peak levels of NF-κB activation (Fig. 1A). Reovirus stimulated nuclear localization of RelA in wild-type MEFs, as did the cytokine TNF-α (Fig. 5B), a potent IKK agonist (26, 91). Similar results were obtained with nuclear extracts from reovirus-infected MEFs lacking IKKβ (Fig. 5B). However, this response was diminished in MEFs lacking IKKα (Fig. 5B), indicating preferential usage of IKKα relative to IKKβ. MEFs lacking the regulatory subunit IKKγ/Nemo also were incapable of reovirus-mediated RelA nuclear localization (Fig. 5B). EMSA studies using nuclear extracts from the same panel of infected cells confirmed these results (Fig. 5C and D). NF-κB DNA-binding activity was detected in wild-type MEFs and IKKβ-deficient MEFs but not in MEFs lacking IKKα or IKKγ/Nemo. Differences in reovirus-mediated signal transduction in IKK-deficient MEFs could not be attributed to differences in viral infection or growth (data not shown). Thus, these findings provide strong evidence that IKKα and IKKγ/Nemo are required for reovirus-induced NF-κB activation.

FIG. 5.

IKKα and IKKγ/Nemo are required for reovirus-induced activation of NF-κB. (A) 293T cells were transfected with plasmids encoding shRNAs specific for IKKα, IKKβ, or IKKγ/Nemo or a negative control shRNA (Neg. Con.). After incubation at 37°C for 48 h, cells were cotransfected with plasmids encoding IKK subunit-specific shRNAs, pNF-κB-Luc, and pRenilla-Luc. Cells were treated with 10 ng/ml of TNF-α and adsorbed with T3D at an MOI of 100 PFU/ml or mock infected prior to assessments of luciferase activity in cell-culture lysates. The results are expressed as the ratio of normalized luciferase activity from infected cell lysates to that from mock-infected lysates for triplicate samples. Error bars indicate standard deviations. (B) Wild-type MEFs or MEFs deficient in IKKα, IKKβ, or IKKγ/Nemo were uninfected (0 h), mock infected (Mock), infected with reovirus T3D at an MOI of 100 PFU/cell for 8 h, or treated with 20 ng/ml of TNF-α for 1 h. Nuclear extracts were resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and immunoblotted by using a RelA-specific antiserum. (C) Nuclear extracts from the experiment shown in panel B were incubated with a radiolabeled NF-κB consensus oligonucleotide. Resulting protein-oligonucleotide complexes were resolved by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, dried, and exposed to film. NF-κB-containing complexes are indicated. (D) Band intensity was quantified by determining the number of PSL units relative to that in uninfected cells for three independent experiments. Error bars indicate standard deviations. *, P < 0.05 as determined by Student's t test in comparison to mock-treated cells (0 h).

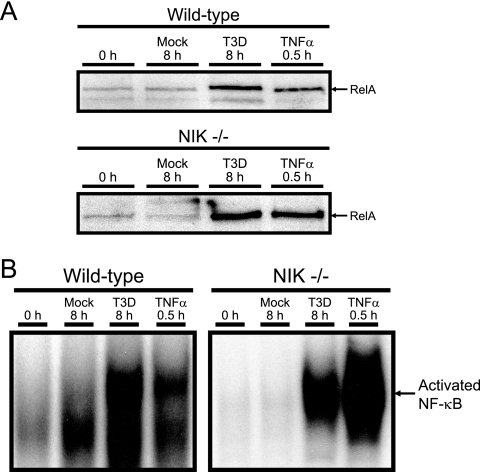

The protein kinase NIK phosphorylates and activates IKKα following cellular stimulation with agonists of the alternative NF-κB pathway, such as lymphotoxin-β (43, 49). To determine whether NIK is required for NF-κB activation by reovirus, we monitored this response in NIK-deficient MEFs by immunoblotting and EMSA (Fig. 6). Reovirus infection resulted in NF-κB activation in both wild-type and NIK-deficient MEFs, indicating that NIK is dispensable for reovirus-induced NF-κB activation. Taken together, these data confirm a requirement for endogenous IKK in the mechanism by which reovirus activates NF-κB and demonstrate that this virus selectively utilizes IKKα and not IKKβ to drive the canonical branch of the NF-κB signaling pathway. Surprisingly, IKKγ/Nemo, which is known to regulate IKKβ rather than IKKα, is also required for NF-κB activation by reovirus, but NIK is dispensable.

FIG. 6.

Reovirus-induced activation of NF-κB in NIK-deficient cells. (A) Wild-type MEFs or NIK-deficient MEFs were uninfected (0 h), mock infected (Mock), infected with reovirus T3D at an MOI of 1,000 PFU/cell for 8 h, or treated with 20 ng/ml of TNF-α for 30 min. Nuclear extracts were resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and immunoblotted by using a RelA-specific antiserum. (B) Nuclear extracts from the experiment shown in panel A were incubated with a radiolabeled NF-κB consensus oligonucleotide. The resulting protein-oligonucleotide complexes were resolved by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, dried, and exposed to film. NF-κB-containing complexes are indicated.

IKKα and IKKγ/Nemo are required for reovirus-induced apoptosis.

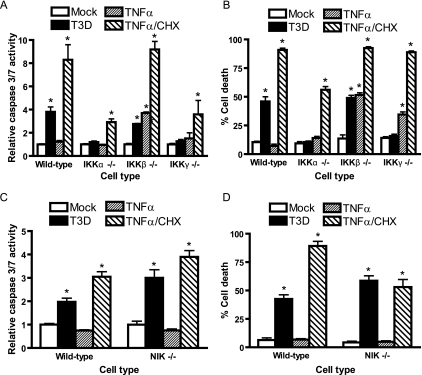

Since IKKα and IKKγ/Nemo mediate NF-κB activation following reovirus infection (Fig. 5), we examined whether IKK stimulation by reovirus is required for apoptotic cell death. IKK-deficient MEFs were infected with reovirus T3D, and apoptosis was assessed by quantitation of caspase 3/7 activity (Fig. 7A). Levels of activated caspase 3/7 following infection of wild-type and IKKβ-deficient MEFs were substantially greater than those following infection of MEFs deficient in either IKKα or IKKγ/Nemo. To corroborate these results, we tested wild-type and IKK subunit-deficient MEFs for viability following infection with T3D (Fig. 7B). A significantly greater percentage of IKKα- and IKKγ-deficient MEFs than wild-type and IKKβ-deficient MEFs remained viable during the time course of reovirus infection.

FIG. 7.

IKKα and IKKγ/Nemo are required for reovirus-induced apoptosis. Wild-type MEFs or (A) MEFs deficient in IKKα, IKKβ, IKKγ/Nemo, or (C) NIK were mock infected (Mock), infected with reovirus T3D at an MOI of 1,000 PFU/cell for 24 h (T3D), treated with 10 ng/ml of TNF-α for 12 h (TNFα), or treated with 10 ng/ml of TNF-α and 10 μg/ml of cycloheximide for 12 h (TNFα/CHX). Caspase 3/7 activity was quantified by using a luminescent substrate. The results are expressed as the mean caspase activity relative to that of mock-infected cells for three independent experiments. Wild-type MEFs, (B) IKK-deficient MEFs, or (D) NIK-deficient MEFs were mock infected, infected with reovirus T3D at an MOI of 1,000 PFU/cell for 48 h, treated with 10 ng/ml of TNF-α for 24 h, or treated with 10 ng/ml of TNF-α and 10 μg/ml of cycloheximide for 24 h. Cell viability was quantified by trypan blue exclusion. The results are expressed as the mean percentage of cell death for three independent experiments. Error bars indicate standard deviations. *, P < 0.05 as determined by Student's t test in comparison to mock-infected cells.

To determine whether NIK is required for apoptosis induction following reovirus infection, NIK-deficient MEFs were infected with reovirus T3D, and apoptosis was assessed by quantification of caspase 3/7 activity (Fig. 7C). Levels of caspase 3/7 activity in MEFs deficient in NIK were comparable to those in wild-type cells following infection with T3D. In parallel with these results, we observed no remarkable difference in the viability of wild-type and of NIK-deficient MEFs following T3D infection (Fig. 7D), suggesting that NIK is not required for reovirus-induced apoptosis.

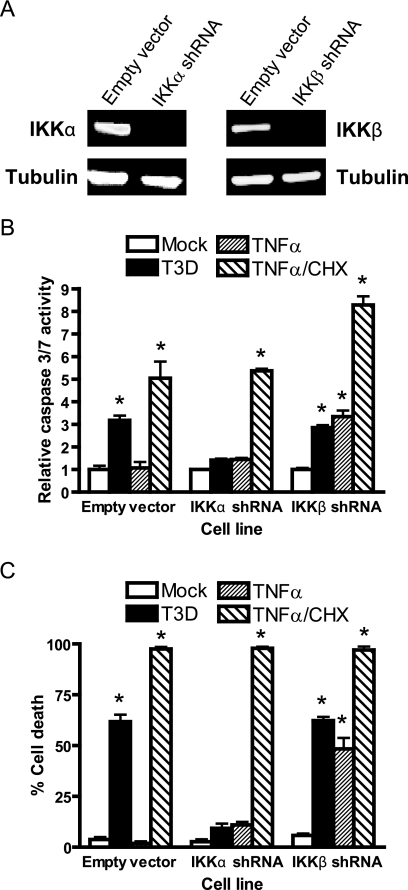

To confirm a requirement for IKKα in reovirus-induced apoptosis using an independent approach, we examined whether HeLa cells stably expressing retrovirus-transduced shRNAs for either IKKα or IKKβ were capable of undergoing apoptosis in response to reovirus. Steady-state levels of IKKα and IKKβ in the respective shRNA-expressing cells were significantly reduced in comparison to levels of those proteins in cells expressing an empty retrovirus vector control (Fig. 8A). IKKα knockdown resulted in a marked decrease in reovirus-induced apoptosis assessed by both caspase 3/7 activity (Fig. 8B) and cell viability (Fig. 8C) in comparison to levels of apoptosis in cells transduced with an IKKβ-specific shRNA or the empty retrovirus vector control. Together, these functional data with IKK-specific siRNA-mediated knockdown and IKK- and NIK-deficient MEFs strongly correlate with the capacity of reovirus to modulate IκBα and NF-κB during infection (Fig. 1 to 6). Our findings indicate that both IKKα and IKKγ/Nemo, but neither IKKβ nor NIK, are required for the activation of NF-κB and induction of apoptosis in response to reovirus.

FIG. 8.

Knockdown of IKKα diminishes apoptosis in response to reovirus. (A) Extracts of HeLa cells transduced with retroviruses containing empty vector or encoding shRNAs specific for either IKKα or IKKβ were resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and immunoblotted by using IKKα-, IKKβ-, or tubulin-specific antiserum. Immunoblots were scanned and quantified by using Odyssey software. (B) HeLa cells stably expressing empty vector or shRNAs specific for either IKKα or IKKβ were mock infected (Mock), infected with reovirus T3D at an MOI of 1,000 PFU/cell for 24 h (T3D), treated with 10 ng/ml of TNF-α for 12 h (TNFα), or treated with 10 ng/ml of TNF-α and 10 μg/ml of cycloheximide for 12 h (TNFα/CHX). Caspase 3/7 activity was quantified by using a luminescent substrate. The results are expressed as the mean caspase activity relative to that of mock-infected cells for three independent experiments. (C) HeLa cells stably expressing empty vector or shRNAs specific for either IKKα or IKKβ were mock infected, infected with reovirus T3D at an MOI of 1,000 PFU/cell for 48 h, treated with 10 ng/ml of TNF-α for 24 h, or treated with 10 ng/ml of TNF-α and 10 μg/ml of cycloheximide for 24 h. Cell viability was quantified by trypan blue exclusion. The results are expressed as the mean percentage of cell death for three independent experiments. Error bars indicate standard deviations. *, P < 0.05 as determined by Student's t test in comparison to mock-infected cells.

DISCUSSION

Apoptosis is a genetically programmed form of cell death that plays an important regulatory role in a wide spectrum of biological processes. Many viruses are capable of inducing apoptosis of infected cells (63). In some cases, apoptosis triggered by viral infection may serve as a component of host defense to limit viral replication or spread. In other instances, apoptosis may enhance viral infection by facilitating viral dissemination or allowing virus to evade host inflammatory responses (5, 6, 63). Apoptosis plays an important role in the various patterns of disease caused by reovirus infection (22, 23, 53, 54). Although we previously uncovered an essential function for NF-κB activation in reovirus-induced apoptosis (20), it was not known how reovirus activates this signal-transduction mechanism. Results reported here identify constituents of the NF-κB signaling apparatus induced by reovirus and provide evidence that NF-κB activation during reovirus infection requires select components of the classical and alternative NF-κB signaling pathways.

Using siRNA-mediated knockdown of individual IKK subunits and IKK subunit-deficient MEFs, we demonstrate that reovirus-infected cells lacking IKKα are impaired for NF-κB activation (Fig. 5) and apoptotic programming (Fig. 7 and 8), whereas both of these processes are operative in cells lacking IKKβ. Despite its preferential usage of IKKα, reovirus retains the capacity to elicit both NF-κB activation and apoptosis in the absence of NIK (Fig. 6 and 7), a known activator of IKKα in cytokine-treated cells (43, 66). Furthermore, degradation of the RNA or targeted disruption of the gene encoding IKKγ/Nemo, which is dispensable for cytokine-induced activation of IKKα (16, 24), significantly attenuates reovirus-induced NF-κB activation and apoptosis (Fig. 5 and 7). Our findings with NIK and IKKγ/Nemo suggest that reovirus activates the canonical NF-κB pathway by a novel mechanism involving IKKα instead of IKKβ. The simplest interpretation of these results is that reovirus accesses the cellular NF-κB machinery by directly interfacing with IKKα/IKKγ complexes, with IKKγ/Nemo serving as an adaptor that docks one or more reovirus gene products. In keeping with this possibility, IKKγ/Nemo tethers the HTLV1 Tax protein to IKK complexes, resulting in the persistent activation of IKKβ and NF-κB (9, 14). In what may be another related finding, IKKγ/Nemo also is required for Tax-induced activation of IKKα (84). Although data emerging from studies of IKKβ-deficient mice suggest the presence of functional IKKα/IKKγ complexes (40, 42, 61, 72), direct evidence for the existence of IKKα/IKKγ complexes in wild-type animals has not been reported. Notwithstanding, our results clearly establish that reovirus activates NF-κB and downstream proapoptotic genes via a mechanism involving IKKα but not IKKβ.

The principle in vivo substrate of IKKβ is IκBα (26, 50, 58). This cytoplasmic inhibitor tightly controls the nuclear translocation of p50/RelA dimers (3), effectors of the classical NF-κB pathway (reviewed in references 4, 28, and 30). The principle in vivo substrate of IKKα is p100/NF-κB2 (66), an integral inhibitor in the alternative NF-κB pathway that retains the RelB transactivator protein in the cytoplasm (66, 71). Following IKKα-mediated phosphorylation, p100 is processed to p52 via a proteasome-dependent mechanism, permitting the nuclear entry of p52/RelB complexes (66, 71). Given these distinct mechanisms, our findings with reovirus-infected cells suggest an unconventional function for IKKα in substrate targeting. Specifically, we were unable to detect either p52 or RelB DNA-binding activity in nuclear extracts from cells following 4 to 8 h of reovirus infection (Fig. 1B). Instead, at these early time points, the predominant Rel species detected were p50 and RelA (Fig. 1B), which are primarily under IκBα control (2, 3). Consistent with this Rel profile, IκBα protein levels were significantly reduced by 4 h postinfection (Fig. 3). Although p100 processing to p52 was observed at late time points during reovirus infection (16 h), it seems unlikely that this very delayed response contributes to the more rapidly developing signals required for apoptosis (19, 20, 60). Accordingly, we propose that IKKα rather than IKKβ targets IκBα for proteolytic destruction and regulates the nuclear translocation of p50/RelA complexes in reovirus-infected cells. This working model is fully concordant with the phenotype of cell lines deficient for either IKKα, p50, or p65/RelA, all of which are impaired for reovirus-induced NF-κB activation and proapoptotic signaling (Fig. 5 and 7) (20). In agreement with this model, prior studies with recombinant proteins indicate that IKKα can efficiently phosphorylate NF-κB-bound forms of IκBα in vitro (39, 90). Additionally, RANKL (receptor activator of NF-κB ligand)-mediated signaling of epithelial cells in vitro requires IKKα-dependent phosphorylation of IκBα to activate NF-κB (8).

Both IKKα and IKKβ contain regulatory serine phosphoacceptors in their so-called T-loop domains (25, 50). Signal-dependent phosphorylation of the T-loop serines in IKKα and IKKβ is a prerequisite for their catalytic activation (25). Based on in vitro studies with recombinant proteins, IKKα and IKKβ can autophosphorylate at these T-loop serines (25, 65, 73). Physiologic agonists of the alternative NF-κB pathway stimulate T-loop phosphorylation and activation of IKKα via the upstream kinase NIK (43, 66, 85). However, NIK is dispensable in the mechanism by which reovirus induces NF-κB activation and apoptosis (Fig. 6 and 7). Which signal transducers couple reovirus to the IKKs? Experiments using pharmacological inhibitors suggest that NF-κB-dependent apoptotic signaling is triggered by viral replication steps that occur after disassembly but prior to RNA synthesis (19). Strain-specific differences in the capacity of reovirus to induce apoptosis segregate with the viral genes encoding the σ1 and μ1 proteins (18, 60, 77), which play important roles in viral attachment (38, 81) and membrane penetration (10, 11, 45), respectively. Importantly, transient expression of μ1 is sufficient to induce apoptosis in cell culture (17), implicating this protein in the reovirus/NF-κB signaling axis. We envision three potential mechanisms by which μ1, or perhaps another viral gene product, initiates NF-κB signal transduction during reovirus infection. First, μ1 may activate viral sensors that engage the adaptor protein IPS-1 (beta interferon promoter stimulator 1), which mediates the activation of NF-κB in response to viral infections by recruiting TNF-associated factor 6 to the signaling complex (37, 51, 67, 86). Second, μ1 may activate a cellular kinase distinct from NIK that phosphorylates the T loop of IKKα. Third, μ1 may interact with IKK complexes directly, leading to conformational changes that stimulate oligomerization and selectively trigger IKKγ-dependent autophosphorylation of the T loop in IKKα rather than IKKβ (36, 57). Studies to test these models for reovirus-induced activation of IKKα are currently under way.

Reovirus infection leads to NF-κB activation in numerous cell types (15, 20, 54). However, the functional consequences of NF-κB activation in vivo differ depending on the infected tissue. NF-κB activation in the CNS leads to high levels of neuronal apoptosis and encephalitis (54). In contrast, NF-κB activation in the heart leads to IFN-β production, which limits viral replication and protects against apoptosis (54). In the absence of NF-κB signaling, reovirus infection induces widespread apoptotic damage to cardiac myocytes, resulting in myocarditis. Mechanisms underlying the divergent cellular fates following NF-κB activation by reovirus in vivo remain unclear. Considering the results presented in this report, these mechanisms may involve tissue-specific activation of different IKK subunits, which in turn may influence the composition of nuclear NF-κB complexes. Experiments using tissue-specific IKKα- or IKKβ-deficient mice should clarify the function of IKK in reovirus-induced disease.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of our laboratory for many helpful discussions and Jim Chappell, Geoff Holm, and Denise Wetzel for careful reviews of the manuscript. We thank Karl Ziegelbauer and Bayer Health Care AG for Compound A, Amgen for NIK-deficient cells, and Robert Schreiber for NIK wild-type cells. K.B.M. thanks Garry Nolan for Phoenix A packaging cells, Ross Dickins for the pLMP and pTMP retroviral vectors, and Dorothee Vicogne for technical assistance.

This research was supported by Public Health Service awards T32 CA09385 (J.A.C.), R01 GM066882 (K.B.M.), R01 AI52379 and CA82556 (D.W.B.), and R01 AI50080 (T.S.D.) and the Elizabeth B. Lamb Center for Pediatric Research. Additional support was provided by Public Health Service awards CA68485 for the Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center and DK20593 for the Vanderbilt Diabetes Research and Training Center.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 22 November 2006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anest, V., J. L. Hanson, P. C. Cogswell, K. A. Steinbrecher, B. D. Strahl, and A. S. Baldwin. 2003. A nucleosomal function for IκB kinase-α in NF-κB-dependent gene expression. Nature 423:659-663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baeuerle, P., and D. Baltimore. 1989. A 65-kD subunit of active NF-κB is required for inhibition of NF-κB by IκB. Genes Dev. 3:1689-1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baeuerle, P., and D. Baltimore. 1988. IκB: a specific inhibitor of the NF-κB transcription factor. Science 242:540-546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonizzi, G., and M. Karin. 2004. The two NF-κB activation pathways and their role in innate and adaptive immunity. Trends Immunol. 25:280-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowie, A. G., J. Zhan, and W. L. Marshall. 2004. Viral appropriation of apoptotic and NF-κB signaling pathways. J. Cell. Biochem. 91:1099-1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boya, P., A. L. Pauleau, D. Poncet, R. A. Gonzalez-Polo, N. Zamzami, and G. Kroemer. 2004. Viral proteins targeting mitochondria: controlling cell death. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1659:178-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown, K., S. Gerstberger, L. Carlson, G. Franzoso, and U. Siebenlist. 1995. Control of IκB-α proteolysis by site-specific, signal-induced phosphorylation. Science 267:1485-1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cao, Y., G. Bonizzi, T. N. Seagroves, F. R. Greten, R. Johnson, E. V. Schmidt, and M. Karin. 2001. IKKalpha provides an essential link between RANK signaling and cyclin D1 expression during mammary gland development. Cell 107:763-775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carter, R. S., B. C. Geyer, M. Xie, C. A. Acevedo-Suarez, and D. W. Ballard. 2001. Persistent activation of NF-κB by the tax transforming protein involves chronic phosphorylation of IκB kinase subunits IKKβ and IKKγ. J. Biol. Chem. 276:24445-24448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chandran, K., D. L. Farsetta, and M. L. Nibert. 2002. Strategy for nonenveloped virus entry: a hydrophobic conformer of the reovirus membrane penetration protein μ1 mediates membrane disruption. J. Virol. 76:9920-9933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chandran, K., J. S. Parker, M. Ehrlich, T. Kirchhausen, and M. L. Nibert. 2003. The delta region of outer-capsid protein μ1 undergoes conformational change and release from reovirus particles during cell entry. J. Virol. 77:13361-13375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen, Z., J. Hagler, V. J. Palombella, F. Melandri, D. Scherer, D. Ballard, and T. Maniatis. 1995. Signal-induced site-specific phosphorylation targets IκBα to the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Genes Dev. 9:1586-1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chu, Z. L., J. A. DiDonato, J. Hawiger, and D. W. Ballard. 1998. The tax oncoprotein of human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 associates with and persistently activates IκB kinases containing IKKα and IKKβ. J. Biol. Chem. 273:15891-15894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chu, Z. L., Y. A. Shin, J. M. Yang, J. A. DiDonato, and D. W. Ballard. 1999. IKKγ mediates the interaction of cellular IκB kinases with the tax transforming protein of human T cell leukemia virus type 1. J. Biol. Chem. 274:15297-15300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clarke, P., S. M. Meintzer, L. A. Moffitt, and K. L. Tyler. 2003. Two distinct phases of virus-induced nuclear factor kappa B regulation enhance tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand-mediated apoptosis in virus-infected cells. J. Biol. Chem. 278:18092-18100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Claudio, E., K. Brown, S. Park, H. Wang, and U. Siebenlist. 2002. BAFF-induced NEMO-independent processing of NF-κB2 in maturing B cells. Nat. Immunol. 3:958-965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coffey, C. M., A. Sheh, I. S. Kim, K. Chandran, M. L. Nibert, and J. S. Parker. 2006. Reovirus outer capsid protein μ1 induces apoptosis and associates with lipid droplets, endoplasmic reticulum, and mitochondria. J. Virol. 80:8422-8438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Connolly, J. L., E. S. Barton, and T. S. Dermody. 2001. Reovirus binding to cell surface sialic acid potentiates virus-induced apoptosis. J. Virol. 75:4029-4039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Connolly, J. L., and T. S. Dermody. 2002. Virion disassembly is required for apoptosis induced by reovirus. J. Virol. 76:1632-1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Connolly, J. L., S. E. Rodgers, P. Clarke, D. W. Ballard, L. D. Kerr, K. L. Tyler, and T. S. Dermody. 2000. Reovirus-induced apoptosis requires activation of transcription factor NF-κB. J. Virol. 74:2981-2989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Danthi, P., M. W. Hansberger, J. A. Campbell, J. C. Forrest, and T. S. Dermody. 2006. JAM-A-independent, antibody-mediated uptake of reovirus into cells leads to apoptosis. J. Virol. 80:1261-1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DeBiasi, R., C. Edelstein, B. Sherry, and K. Tyler. 2001. Calpain inhibition protects against virus-induced apoptotic myocardial injury. J. Virol. 75:351-361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeBiasi, R. L., B. A. Robinson, B. Sherry, R. Bouchard, R. D. Brown, M. Rizeq, C. Long, and K. L. Tyler. 2004. Caspase inhibition protects against reovirus-induced myocardial injury in vitro and in vivo. J. Virol. 78:11040-11050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dejardin, E., N. M. Droin, M. Delhase, E. Haas, Y. Cao, C. Makris, Z. W. Li, M. Karin, C. F. Ware, and D. R. Green. 2002. The lymphotoxin-beta receptor induces different patterns of gene expression via two NF-κB pathways. Immunity 17:525-535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Delhase, M., M. Hayakawa, Y. Chen, and M. Karin. 1999. Positive and negative regulation of IκB kinase activity through IKKβ subunit phosphorylation. Science 284:309-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DiDonato, J. A., M. Hayakawa, D. M. Rothwarf, E. Zandi, and M. Karin. 1997. A cytokine-responsive IκB kinase that activates the transcription factor NF-κB. Nature 388:548-554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Furlong, D. B., M. L. Nibert, and B. N. Fields. 1988. Sigma 1 protein of mammalian reoviruses extends from the surfaces of viral particles. J. Virol. 62:246-256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ghosh, S., and M. Karin. 2002. Missing pieces in the NF-κB puzzle. Cell 109(Suppl.):S81-S96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grumont, R. J., I. B. Richardson, C. Gaff, and S. Gerondakis. 1993. rel/NF-κB nuclear complexes that bind κB sites in the murine c-rel promoter are required for constitutive c-rel transcription in B-cells. Cell Growth Differ. 4:731-743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hayden, M. S., and S. Ghosh. 2004. Signaling to NF-κB. Genes Dev. 18:2195-2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heusch, M., L. Lin, R. Geleziunas, and W. C. Greene. 1999. The generation of nfkb2 p52: mechanism and efficiency. Oncogene 18:6201-6208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoberg, J. E., A. E. Popko, C. S. Ramsey, and M. W. Mayo. 2006. IκB kinase α-mediated derepression of SMRT potentiates acetylation of RelA/p65 by p300. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26:457-471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoberg, J. E., F. Yeung, and M. W. Mayo. 2004. SMRT derepression by the IκB kinase α: a prerequisite to NF-κB transcription and survival. Mol. Cell 16:245-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hu, Y., V. Baud, M. Delhase, P. Zhang, T. Deerinck, M. Ellisman, R. Johnson, and M. Karin. 1999. Abnormal morphogenesis but intact IKK activation in mice lacking the IKKα subunit of IκB kinase. Science 284:316-320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huynh, Q. K., H. Boddupalli, S. A. Rouw, C. M. Koboldt, T. Hall, C. Sommers, S. D. Hauser, J. L. Pierce, R. G. Combs, B. A. Reitz, J. A. Diaz-Collier, R. A. Weinberg, B. L. Hood, B. F. Kilpatrick, and C. S. Tripp. 2000. Characterization of the recombinant IKK1/IKK2 heterodimer. Mechanisms regulating kinase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 275:25883-25891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Inohara, N., T. Koseki, J. Lin, L. del Peso, P. C. Lucas, F. F. Chen, Y. Ogura, and G. Nunez. 2000. An induced proximity model for NF-κB activation in the Nod1/RICK and RIP signaling pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 275:27823-27831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kawai, T., K. Takahashi, S. Sato, C. Coban, H. Kumar, H. Kato, K. J. Ishii, O. Takeuchi, and S. Akira. 2005. IPS-1, an adaptor triggering RIG-I- and Mda5-mediated type I interferon induction. Nat. Immunol. 6:981-988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee, P. W., E. C. Hayes, and W. K. Joklik. 1981. Protein σ1 is the reovirus cell attachment protein. Virology 108:156-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li, J., G. W. Peet, S. S. Pullen, J. Schembri-King, T. C. Warren, K. B. Marcu, M. R. Kehry, R. Barton, and S. Jakes. 1998. Recombinant IκB kinases α and β are direct kinases of IκBα. J. Biol. Chem. 273:30736-30741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li, Q., D. Van Antwerp, F. Mercurio, K. F. Lee, and I. M. Verma. 1999. Severe liver degeneration in mice lacking the IκB kinase 2 gene. Science 284:321-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li, X., P. E. Massa, A. Hanidu, G. W. Peet, P. Aro, A. Savitt, S. Mische, J. Li, and K. B. Marcu. 2002. IKKα, IKKβ, and NEMO/IKKγ are each required for the NF-κB-mediated inflammatory response program. J. Biol. Chem. 277:45129-45140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li, Z. W., W. Chu, Y. Hu, M. Delhase, T. Deerinck, M. Ellisman, R. Johnson, and M. Karin. 1999. The IKKβ subunit of IκB kinase (IKK) is essential for nuclear factor κB activation and prevention of apoptosis. J. Exp. Med. 189:1839-1845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ling, L., Z. Cao, and D. V. Goeddel. 1998. NF-κB-inducing kinase activates IKK-α by phosphorylation of Ser-176. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:3792-3797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Link, E., L. D. Kerr, R. Schreck, U. Zabel, I. Verma, and P. A. Baeuerle. 1992. Purified IκB-β is inactivated upon dephosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 267:239-246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lucia-Jandris, P., J. W. Hooper, and B. N. Fields. 1993. Reovirus M2 gene is associated with chromium release from mouse L cells. J. Virol. 67:5339-5345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Makris, C., V. L. Godfrey, G. Krahn-Senftleben, T. Takahashi, J. L. Roberts, T. Schwarz, L. Feng, R. S. Johnson, and M. Karin. 2000. Female mice heterozygous for IKKγ/NEMO deficiencies develop a dermatopathy similar to the human X-linked disorder incontinentia pigmenti. Mol. Cell. 5:969-979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maniatis, T. 1997. Catalysis by a multiprotein IκB kinase complex. Science 278:818-819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Massa, P. E., X. Li, A. Hanidu, J. Siamas, M. Pariali, J. Pareja, A. G. Savitt, K. M. Catron, J. Li, and K. B. Marcu. 2005. Gene expression profiling in conjunction with physiological rescues of IKKα-null cells with wild type or mutant IKKα reveals distinct classes of IKKα/NF-κB-dependent genes. J. Biol. Chem. 280:14057-14069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Matsushima, A., T. Kaisho, P. D. Rennert, H. Nakano, K. Kurosawa, D. Uchida, K. Takeda, S. Akira, and M. Matsumoto. 2001. Essential role of nuclear factor (NF)-κB-inducing kinase and inhibitor of κB (IκB) kinase α in NF-κB activation through lymphotoxin beta receptor, but not through tumor necrosis factor receptor I. J. Exp. Med. 193:631-636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mercurio, F., H. Zhu, B. W. Murray, A. Shevchenko, B. L. Bennett, J. Li, D. B. Young, M. Barbosa, M. Mann, A. Manning, and A. Rao. 1997. IKK-1 and IKK-2: cytokine-activated IκB kinases essential for NF-κB activation. Science 278:860-866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Meylan, E., J. Curran, K. Hofmann, D. Moradpour, M. Binder, R. Bartenschlager, and J. Tschopp. 2005. Cardif is an adaptor protein in the RIG-I antiviral pathway and is targeted by hepatitis C virus. Nature 437:1167-1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nibert, M. L., and L. A. Schiff. 2001. Reoviruses and their replication, p. 1679-1728. In D. M. Knipe and P. M. Howley (ed.), Fields virology, 4th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA.

- 53.Oberhaus, S. M., R. L. Smith, G. H. Clayton, T. S. Dermody, and K. L. Tyler. 1997. Reovirus infection and tissue injury in the mouse central nervous system are associated with apoptosis. J. Virol. 71:2100-2106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.O'Donnell, S. M., M. W. Hansberger, J. L. Connolly, J. D. Chappell, M. J. Watson, J. M. Pierce, J. D. Wetzel, W. Han, E. S. Barton, J. C. Forrest, T. Valyi-Nagy, F. E. Yull, T. S. Blackwell, J. N. Rottman, B. Sherry, and T. S. Dermody. 2005. Organ-specific roles for transcription factor NF-κB in reovirus-induced apoptosis and disease. J. Clin. Investig. 115:2341-2350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Paddison, P. J., M. Cleary, J. M. Silva, K. Chang, N. Sheth, R. Sachidanandam, and G. J. Hannon. 2004. Cloning of short hairpin RNAs for gene knockdown in mammalian cells. Nat. Methods 1:163-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Palombella, V., O. Rando, A. Goldberg, and T. Maniatis. 1994. The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway is required for processing the NF-κB1 precursor protein and the activation of NF-κB. Cell 78:773-785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Poyet, J. L., S. M. Srinivasula, J. H. Lin, T. Fernandes-Alnemri, S. Yamaoka, P. N. Tsichlis, and E. S. Alnemri. 2000. Activation of the IκB kinases by RIP via IKKγ/NEMO-mediated oligomerization. J. Biol. Chem. 275:37966-37977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Regnier, C. H., H. Y. Song, X. Gao, D. V. Goeddel, Z. Cao, and M. Rothe. 1997. Identification and characterization of an IκB kinase. Cell 90:373-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Richardson-Burns, S. M., D. J. Kominsky, and K. L. Tyler. 2002. Reovirus-induced neuronal apoptosis is mediated by caspase 3 and is associated with the activation of death receptors. J. Neurovirol. 8:365-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rodgers, S. E., E. S. Barton, S. M. Oberhaus, B. Pike, C. A. Gibson, K. L. Tyler, and T. S. Dermody. 1997. Reovirus-induced apoptosis of MDCK cells is not linked to viral yield and is blocked by Bcl-2. J. Virol. 71:2540-2546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rothwarf, D. M., and M. Karin. 1999. NF-κB activation pathway: a paradigm in information transfer from membrane to nucleus. Sci. STKE 1999:RE1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rothwarf, D. M., E. Zandi, G. Natoli, and M. Karin. 1998. IKK-γ is an essential regulatory subunit of the IκB kinase complex. Nature 395:297-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Roulston, A., R. C. Marcellus, and P. E. Branton. 1999. Viruses and apoptosis. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 53:577-628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rudolph, D., W. C. Yeh, A. Wakeham, B. Rudolph, D. Nallainathan, J. Potter, A. J. Elia, and T. W. Mak. 2000. Severe liver degeneration and lack of NF-κB activation in NEMO/IKKγ-deficient mice. Genes Dev. 14:854-862. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schomer-Miller, B., T. Higashimoto, Y. K. Lee, and E. Zandi. 2006. Regulation of IκB kinase (IKK) complex by IKKγ-dependent phosphorylation of the T-loop and C terminus of IKKβ. J. Biol. Chem. 281:15268-15276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Senftleben, U., Y. Cao, G. Xiao, F. R. Greten, G. Krahn, G. Bonizzi, Y. Chen, Y. Hu, A. Fong, S. C. Sun, and M. Karin. 2001. Activation by IKKα of a second, evolutionary conserved, NF-κB signaling pathway. Science 293:1495-1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Seth, R. B., L. Sun, C. K. Ea, and Z. J. Chen. 2005. Identification and characterization of MAVS, a mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein that activates NF-κB and IRF 3. Cell 122:669-682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Simeonidis, S., S. Liang, G. Chen, and D. Thanos. 1997. Cloning and functional characterization of mouse IkappaBepsilon. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:14372-14377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sizemore, N., N. Lerner, N. Dombrowski, H. Sakurai, and G. R. Stark. 2002. Distinct roles of the IκB kinase α and β subunits in liberating nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) from IκB and in phosphorylating the p65 subunit of NF-κB. J. Biol. Chem. 277:3863-3869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Smith, R. E., H. J. Zweerink, and W. K. Joklik. 1969. Polypeptide components of virions, top component and cores of reovirus type 3. Virology 39:791-810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Solan, N. J., H. Miyoshi, E. M. Carmona, G. D. Bren, and C. V. Paya. 2002. RelB cellular regulation and transcriptional activity are regulated by p100. J. Biol. Chem. 277:1405-1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tanaka, M., M. E. Fuentes, K. Yamaguchi, M. H. Durnin, S. A. Dalrymple, K. L. Hardy, and D. V. Goeddel. 1999. Embryonic lethality, liver degeneration, and impaired NF-κB activation in IKK-β-deficient mice. Immunity 10:421-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tang, E. D., N. Inohara, C. Y. Wang, G. Nunez, and K. L. Guan. 2003. Roles for homotypic interactions and transautophosphorylation in IκB kinase β (IKKβ) activation. J. Biol. Chem. 278:38566-38570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Thompson, J. E., R. J. Phillips, H. Erdjument-Bromage, P. Tempst, and S. Ghosh. 1995. IκB-β regulates the persistent response in a biphasic activation of NF-κB. Cell 80:573-582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Traenckner, E. B., H. L. Pahl, T. Henkel, K. N. Schmidt, S. Wilk, and P. A. Baeuerle. 1995. Phosphorylation of human IκB-α on serines 32 and 36 controls IκB-α proteolysis and NF-κB activation in response to diverse stimuli. EMBO J. 14:2876-2883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tyler, K. L. 2001. Mammalian reoviruses, p. 1729-1745. In D. M. Knipe and P. M. Howley (ed.), Fields virology, 4th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA.

- 77.Tyler, K. L., M. K. Squier, S. E. Rodgers, S. E. Schneider, S. M. Oberhaus, T. A. Grdina, J. J. Cohen, and T. S. Dermody. 1995. Differences in the capacity of reovirus strains to induce apoptosis are determined by the viral attachment protein σ1. J. Virol. 69:6972-6979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Verma, I. M., and J. Stevenson. 1997. IκB kinase: beginning, not the end. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:11758-11760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Verma, I. M., J. K. Stevenson, E. M. Schwarz, D. Van Antwerp, and S. Miyamoto. 1995. Rel/NF-κB/IκB family: intimate tales of association and disassociation. Genes Dev. 9:2723-2735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Virgin, H. W. IV, R. Bassel-Duby, B. N. Fields, and K. L. Tyler. 1988. Antibody protects against lethal infection with the neurally spreading reovirus type 3 (Dearing). J. Virol. 62:4594-4604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Weiner, H. L., K. A. Ault, and B. N. Fields. 1980. Interaction of reovirus with cell surface receptors. I. Murine and human lymphocytes have a receptor for the hemagglutinin of reovirus type 3. J. Immunol. 124:2143-2148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Whiteside, S. T., J. C. Epinat, N. R. Rice, and A. Israel. 1997. IκBɛ, a novel member of the IκB family, controls RelA and cRel NF-κB activity. EMBO J. 16:1413-1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wong, G., and D. Goeddel. 1994. Fas antigen and p55 TNF receptor signal apoptosis through distinct pathways. J. Immunol. 152:1751-1755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Xiao, G., M. E. Cvijic, A. Fong, E. W. Harhaj, M. T. Uhlik, M. Waterfield, and S. C. Sun. 2001. Retroviral oncoprotein Tax induces processing of NF-κB2/p100 in T cells: evidence for the involvement of IKKα. EMBO J. 20:6805-6815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Xiao, G., E. W. Harhaj, and S. C. Sun. 2001. NF-κB-inducing kinase regulates the processing of NF-κB2 p100. Mol. Cell. Biol. 7:401-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Xu, L. G., Y. Y. Wang, K. J. Han, L. Y. Li, Z. Zhai, and H. B. Shu. 2005. VISA is an adapter protein required for virus-triggered IFN-β signaling. Mol. Cell 19:727-740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yamamoto, Y., U. N. Verma, S. Prajapati, Y. T. Kwak, and R. B. Gaynor. 2003. Histone H3 phosphorylation by IKK-α is critical for cytokine-induced gene expression. Nature 423:655-659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yamaoka, S., G. Courtois, C. Bessia, S. T. Whiteside, R. Weil, F. Agou, H. E. Kirk, R. J. Kay, and A. Israel. 1998. Complementation cloning of NEMO, a component of the IκB kinase complex essential for NF-κB activation. Cell 93:1231-1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yin, L., L. Wu, H. Wesche, C. D. Arthur, J. M. White, D. V. Goeddel, and R. D. Schreiber. 2001. Defective lymphotoxin-β receptor-induced NF-κB transcriptional activity in NIK-deficient mice. Science 291:2162-2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zandi, E., Y. Chen, and M. Karin. 1998. Direct phosphorylation of IκB by IKKα and IKKβ: discrimination between free and NF-κB-bound substrate. Science 281:1360-1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zandi, E., D. M. Rothwarf, M. Delhase, M. Hayakawa, and M. Karin. 1997. The IκB kinase complex (IKK) contains two kinase subunits, IKKα and IKKβ, necessary for IκB phosphorylation and NF-κB activation. Cell 91:243-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ziegelbauer, K., F. Gantner, N. W. Lukacs, A. Berlin, K. Fuchikami, T. Niki, K. Sakai, H. Inbe, K. Takeshita, M. Ishimori, H. Komura, T. Murata, T. Lowinger, and K. B. Bacon. 2005. A selective novel low-molecular-weight inhibitor of IκB kinase-β (IKK-β) prevents pulmonary inflammation and shows broad anti-inflammatory activity. Br. J. Pharmacol. 145:178-192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]