Abstract

Simian virus 40 (SV40) large tumor antigen (Tag) represents a virus-encoded tumor-specific antigen expressed in many types of human cancers and a potential immunologic target for antitumor responses. Fc receptors are important mediators in the regulation and execution of host effector mechanisms against conditions including infectious diseases, autoimmunity, and cancer. By examining tumor protection in SV40 Tag-immunized wild-type BALB/c mice using an experimental pulmonary metastasis model, we attempted to address whether engagement of the immunoglobulin G Fc receptors (FcγRs) on effector cells is necessary to mediate antitumor responses. All immunized BALB/c FcγR−/− knockout mice developed anti-SV40 Tag antibody responses prior to experimental challenge with a tumorigenic cell line expressing SV40 Tag. However, all mice deficient in the activating FcγRI (CD64) and FcγRIII (CD16) were unable to mount protective immunologic responses against tumor challenge and developed tumor lung foci. In contrast, mice lacking the inhibitory receptor FcγRII (CD32) demonstrated resistance to tumorigenesis. These results underscore the importance of effector cell populations expressing FcγRI/III within this murine tumor model system, and along with the production of a specific humoral immune response, antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) may be a functioning mechanism of tumor clearance. Additionally, these data demonstrate the potential utility of ADCC as a viable approach for targeting vaccination strategies that promote FcγRI/III scavenging pathways against cancer.

Simian virus 40 (SV40) belongs to the Polyomavirus genus and naturally infects immunocompetent rhesus macaque monkeys without signs of pathological disease (5). However, SV40 has been shown to be oncogenic in rodent animal models and can also transform human cell lines in vitro. The virus' transforming ability has been associated primarily with the expression of an early nonstructural protein referred to as large tumor antigen (Tag) that has properties that include binding to and inactivating eukaryotic tumor suppressor proteins. Interestingly, SV40 Tag DNA sequences have been found to be expressed in a number of human malignancies, though SV40's role in causing human tumors is unknown and remains purely associative to date (12). Regardless of these uncertainties surrounding the oncogenic nature of SV40, Tag represents a potential vaccination target against Tag-expressing tumors.

Much focus relies on the role of cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) in mediating tumor rejection due to their potent and efficient nature of cell-to-cell mediated destruction (11). In a classical sense, CTLs become activated by antigen-presenting cells and then recognize and lyse transformed cells that display peptides via the major histocompatibility complex class I pathway. Yet, immune cell components of the humoral response arm are also capable of promoting some level of antitumor activity and remain a viable approach to help thwart the progression of tumor cell growth and metastasis in prophylactic or therapeutic scenarios (18, 21). Antibodies are known to exhibit antitumor activity through a number of mechanisms that include the activation of apoptosis and the blocking of signaling pathways upon binding to a target (14). Cell-mediated cytotoxicity involving NK cells and phagocytes, such as macrophages and neutrophils, can also be induced by antibody bound to tumor antigens. In a scenario termed antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC), the Fc portion of an antibody becomes bound by receptors for the Fc region expressed on macrophages or NK cells and the targeted tumor cell is destroyed.

Immunoglobulin G (IgG) Fc receptors (FcγRs) comprise a subset of surface molecules displayed on immunologic effector cell populations that mediate functions via intracellular signaling cascades due to antibody-antigen cross-linking (23). FcγRI (CD64) and FcγRIII (CD16) are activating receptors distributed on a wide range of myeloid cells. FcγRI is a high-affinity receptor for IgG that is expressed on the surface of monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells (DCs). The low-affinity IgG receptor FcγRIII is found predominately on phagocytes (macrophages and neutrophils) and NK cells. These receptor complexes are composed of a ligand binding α chain and an associated γ chain that contains an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activating motif that serves to initiate cellular activation through signaling pathways upon FcγR binding. As the surface expression and function of FcγRI and FcγRIII are dependent upon the γ subunit, mice with a targeted disruption in the γ subunit gene are unable to express these FcγR types and have impaired effector functions in their respective immunologic cell populations (30).

The Fcγ type II receptor (FcγRIIB) (CD32) is a low-affinity molecule to IgG complexes that is composed of a single-chain polypeptide and is expressed on cells that include monocytes, macrophages, neutrophils, B cells, and activated DCs (24). The cytoplasmic region of FcγRIIB contains an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif that functions to inhibit cellular processes upon receptor ligation. Mice deficient in FcγRIIB can display augmented levels of antibody production as well as the induction of autoimmune reactions, the latter supporting the receptor's role in maintaining peripheral tolerance (20, 31, 37). Additionally, since FcγRIIB has been suggested to modulate the functions of FcγRIII, enhanced levels of ADCC against tumor targets have been observed in FcγRIIB-deficient mice (8). However, with regard to its inhibitory role, FcγRIIB expression on activated DCs has been reported to enhance the humoral immune response due to the presentation of immune complexes to B cells via an FcγRIIB pathway (1, 22, 36).

Our laboratory has previously demonstrated systemic tumor protection with prophylactic immunization in a murine model of experimental tumor metastasis. Following immunization with a recombinant form of SV40 Tag (rSV40 Tag), BALB/c mice were intravenously (i.v.) challenged with an SV40-transformed cell line, designated mKSA (16), that expresses the tumor-specific antigen SV40 Tag. Tumor burden within this experimental metastatic model was quantitated using parameters that include the appearance and number of lung tumor foci. Immunization with rSV40 Tag has previously been shown to activate an SV40 Tag-specific antibody response without detectable levels of SV40 Tag-specific CTLs (4). In vitro assays using cells obtained from peritoneal exudates as effector cells and anti-SV40 Tag antibody harvested from BALB/c mice also revealed that ADCC was a functioning mechanism of tumor cell death and was proposed to play a role in tumor immunity in this system. Further analysis of this induced response to immunization with rSV40 Tag indicated the required roles for Th2-type CD4+ T cells in initiating tumor destruction (15). More specifically, these studies reported that with depletion of CD4+ T cells during the course of immunization, the anti-SV40 Tag antibody humoral response was impaired and mice succumbed to tumor challenge, while CD8+ T-cell-depleted mice survived normally without any observable evidence of tumor cell growth.

To further explore the mechanisms of tumor protection initiated by rSV40 Tag immunization, we examined the role of FcγRs by using genetic knockout strains of mice. In this report, FcγRI/III- or FcγRIIB-deficient mice were immunized with rSV40 Tag and subsequently challenged with a lethal dose of mKSA tumorigenic cells. The results of this study demonstrate the importance of protection mechanisms mediated by FcγR effector pathways within a murine model of experimental pulmonary metastasis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and media.

The SV40-transformed BALB/c mouse kidney fibroblast cell line, designated mKSA (16), was used for tumor cell challenge. mKSA cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with l-glutamine (HyClone, Logan, UT) supplemented with 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids, 500 U/ml penicillin, 500 μg/ml streptomycin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), and 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (HyClone) and incubated in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C. Prior to animal inoculation, cells were detached from flasks by 5 min of exposure to phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and 1 mM EDTA (pH 7.5), washed, and resuspended in PBS to the appropriate cell density.

Mouse immunization and tumor cell challenge.

Six- to 8-week-old BALB/c wild-type and FcγRI/III−/− and FcγRIIB−/− knockout mice (Taconic, Germantown, NY) were obtained and maintained under standard conditions. FcγRI and FcγRIII in the knockout strain FcγRI/III−/− are deficient in the γ chain subunit (30), while FcγRIIB−/− mice lack the normal low-affinity IgG receptor FcγRIIB (31). These knockout strains have previously been shown to lack the appropriate Fc receptors by standard methods including flow cytometry (30, 31). We also validated these results by flow cytometry to observe deficiencies in Fc receptor expression using splenocytes for the appropriate knockout strain and monoclonal antibody reagents specific for murine CD64 and CD16/32 (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) (data not shown). The treatment and care of all animals were in accordance with institutional guidelines and the Animal Welfare Assurance Act.

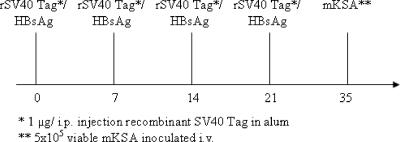

rSV40 Tag was prepared using a baculovirus expression vector system as previously described (17, 27, 28). Groups of 3 wild-type and 10 FcγRI/III−/− and FcγRIIB−/− knockout mice each were immunized intraperitoneally with 1 μg of an alum precipitate of rSV40 Tag a total of four times at 1-week intervals (Fig. 1). Control groups consisted of three mice and were administered recombinant hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) in alum according to the same immunization schedule. Two weeks following the last injection of either rSV40 Tag or HBsAg, mice were challenged i.v. with 5 × 105 viable mKSA tumorigenic cells in 50 μl sterile PBS. Mice were sacrificed at 14 days post-mKSA administration, and tumor burden was determined by examining lung tumor foci as described in detail elsewhere (33, 35). Briefly, lungs were stained with 10% India ink through intratracheal injection and destained with Fekete's solution. To remove subjectivity, visible lung tumor foci were quantitated using computer-assisted video image analysis that incorporated focus density and diameter parameters.

FIG. 1.

Schedule for rSV40 Tag immunization and tumor cell challenge in wild-type and Fcγ−/− mice. BALB/c wild-type and FcγRIIB−/− and FcγRI/III−/− knockout groups were immunized with HBsAg or 1 μg rSV40 Tag in alum at 0, 7, 14, and 21 days. Sera were obtained from mice at 21 and 28 days to assay for anti-SV40 Tag antibody reactivity. On day 35, groups of mice were challenged with 5 × 105 mKSA cells, and 14 days following tumor inoculation, mice were sacrificed and lungs were removed and analyzed for tumor cell focus formation. i.p., intraperitoneal.

ELISA.

SV40 Tag-specific antibody responses and endpoint titer values in immunized mice were determined by an indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as previously described (3, 27, 28). Sera were obtained 7 days following third and fourth immunizations for 3 wild-type and 10 knockout mice in each group. Two hundred nanograms of rSV40 Tag in borate-buffered saline (BBS) was coated onto 96-well plates overnight at 4°C. Nonspecific binding was blocked by the addition of 200 μl 10% normal goat serum in BBS, which was incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Mouse sera were added in triplicate at serial fourfold dilutions in blocking solution, incubated for 1 h at 37°C, and washed with BBS-Tween 20. Fifty microliters of horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG, Fc-specific reagent (Sigma) diluted 1:1,000 in blocking solution was added and incubated for 30 min at 37°C and washed. Plates were then developed using 100 μl 2,2′-azinobis(3-ethylbenzthiazolinesulfonic acid) (ABTS) containing 0.01% H2O2, and the enzyme-substrate reaction was terminated by the addition of 100 μl 5% (wt/vol) sodium dodecyl sulfate. Positive antibody reactivity was determined by using a cutoff optical density value at 405 nm equal to three times the values obtained for a 1:50 dilution of preimmune sera (24). The endpoint titers were determined as the final dilution that resulted in an optical density value above the cutoff value. In similar assays, anti-SV40 Tag antibodies failed to bind the control antigen, HBsAg (data not shown).

Statistics.

The numbers of tumor lung foci were compared between groups using the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test. The statistical significance of the antibody response based on serum titer values was also assessed by logarithmic transformation followed by either the Kruskal-Wallis test or Student's t test. Statistical significance was considered at a P value of <0.05.

RESULTS

FcγR-deficient mice develop an anti-SV40 Tag-specific humoral immune response.

FcγRI/III−/− and FcγRIIB−/− mice were immunized a total of four times with rSV40 Tag (Fig. 1). To examine the ability of these knockout strains to mount an efficient anti-SV40 Tag antibody response, sera were obtained at 7 days post-third and -fourth immunizations and SV40 Tag-specific antibody endpoint titers were determined by ELISA (Table 1). Antibody titer values for FcγRIIB−/− mice ranged from 3,200 to 51,200 (average of 16,640) post-third immunization with rSV40 Tag, while the titer range increased to 3,200 to 204,800 (average of 123,200) following the fourth immunization. Likewise, SV40 Tag-specific antibody titer values for FcγRI/III−/− mice ranged from 51,200 to 204,800 (average of 97,280) after the third rSV40 Tag immunization and 51,200 to 819,200 (average of 250,880) following the fourth immunization. Additionally, wild-type BALB/c mice were immunized with rSV40 Tag following the same schedule (Fig. 1) and SV40 Tag-specific titers were on average 89,600 and 140,800 after the third and fourth rSV40 Tag injections, respectively. The binding properties of sera between wild-type, FcγRI/III−/−, and FcγRIIB−/− mice were shown to be specific to SV40 Tag, as the control groups of mice immunized with HBsAg did not generate a detectable anti-SV40 Tag response by ELISA (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Anti-SV40 Tag antibody titers in sera from wild-type and Fcγ−/− immunized mice

| Mouse strain | Immunization | Titer of antibody [mean (range)] at:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 7 Days post-3rd immunization | 7 Days post-4th immunization | ||

| BALB/c | HBsAg | <50 | <50 |

| rSV40 Tag | 89,600 (12,800-204,800) | 140,800 (12,800-204,800) | |

| FcγRIIB−/− | HBsAg | <50 | <50 |

| rSV40 Tag | 16,640 (3,200-51,200) | 123,200 (3,200-204,800) | |

| FcγRI/III−/− | HBsAg | <50 | <50 |

| rSV40 Tag | 97,280 (51,200-204,800) | 250,880 (51,200-819,200) | |

Based on the reported titer values of SV40 Tag antibody, the knockout strains of mice utilized in this study do not appear to have a deficiency in humoral activity compared to wild-type BALB/c mice. No statistical differences were observed in antibody titers among all groups following the fourth immunization with rSV40 Tag (P < 0.05; Kruskal-Wallis test). Parametric analysis of antibody titers between FcγRI/III−/− and FcγRIIB−/− mice by using Student's t test also failed to demonstrate significance in mean titers, with a P value of <0.05. These data are further supported by the observation that HBsAg-immunized wild-type, FcγRI/III−/−, and FcγRIIB−/− mice generate comparable HBsAg antibody titers (unpublished data).

On average, SV40 Tag antibody titers at 7 days post-fourth immunization between wild-type and FcγRIIB−/− mice were comparable (Table 1). These data are in contrast to previous reports indicating a 5- to 10-fold augmentation in the humoral immune response in FcγRIIB−/− mice (31). Conversely, other studies have also reported enhanced antibody levels due to DC presentation of immune complexes to B cells via FcγRIIB (1, 22, 36). Though the anti-SV40 Tag antibody response in FcγRIIB−/− mice did not differ considerably from that in wild-type immunized groups of mice in this study, it remains plausible that the regulation of the in vivo humoral immune response to rSV40 Tag immunization is neither enhanced nor inhibited to an observable degree by FcγRIIB.

rSV40 Tag immunization does not provide tumor protection in FcγRI/III knockout mice.

To determine the level of protection within our experimental murine model of tumor metastasis, lungs from immunized and challenged mice were quantitated for the presence of tumor foci. FcγRI/III−/− mice were first immunized with rSV40 Tag and subsequently challenged with 5 × 105 mKSA cells (Fig. 1). Fourteen days following mKSA tumor cell challenge, lungs were obtained and stained for the presence and number of lung tumor metastases.

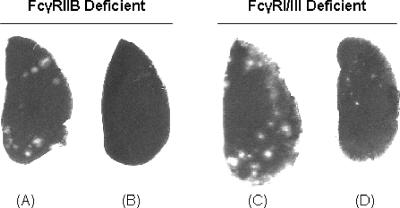

Previous work by our laboratory has reported that wild-type BALB/c mice immunized with rSV40 Tag were protected from the development of lung foci after mKSA challenge. Indeed, all wild-type mice in this study immunized with rSV40 Tag remained lung tumor focus free while those control BALB/c mice immunized with HBsAg developed 14.3 foci on average (range of 12 to 17) (Table 2). In comparison, all five FcγRI/III−/− mice immunized with rSV40 Tag succumbed to tumor challenge based on the formation of tumor lung foci. Representative images of lungs obtained from tumor-challenged FcγRI/III−/− mice immunized with either rSV40 Tag or HBsAg are shown in Fig. 2.

TABLE 2.

Lung metastases in wild-type and Fcγ−/− immunized mice post-tumor cell challenge

| Mouse strain | Immunization | No. of lung foci [mean (range)] |

|---|---|---|

| BALB/c | HBsAg | 14.3 (12-17) |

| rSV40 Tag | 0 | |

| FcγRIIB−/− | HBsAg | 9 (6-11) |

| rSV40 Tag | 0.4 (0-2) | |

| FcγRI/III−/− | HBsAg | 22 (13-27) |

| rSV40 Tag | 3.8 (3-5) |

FIG. 2.

Representative lung tumor foci in immunized FcγRIIB- and FcγRI/III-deficient mice challenged with mKSA. (A and B) FcγRIIB-deficient mice. (A) Tumor focus formation in an HBsAg-immunized mouse. (B) Lack of tumor cell foci in an rSV40 Tag-immunized mouse. (C and D) FcγRI/III-deficient mice. (C) Tumor focus formation in an HBsAg-immunized mouse. (D) Lung of an rSV40 Tag-immunized mouse with observable tumor foci.

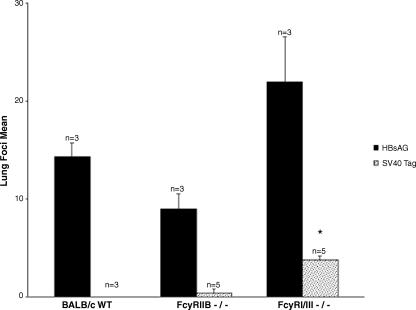

Statistical analysis of lung tumor foci between HBsAg control-immunized wild-type and FcγRI/III−/− mice was not considered significant (P < 0.05; Kruskal-Wallis test), suggesting that no evident immunologic deficiencies in the knockout strain existed with respect to wild-type mice (Fig. 3). Interestingly, the range of lung focus numbers from the rSV40 Tag-immunized FcγRI/III−/−-treated group was less in number than that from control HBsAg-immunized FcγRI/III−/− mice (3 to 5 versus 13 to 27, respectively). This may reflect the previously described role of SV40 Tag-specific CD4+ T cells in tumor immunity (15). Nonetheless, the presence of lung tumor foci in each of the rSV40 Tag-immunized FcγRI/III−/− mice indicated the importance of a functioning FcγRI/III on immunologic effector cells within this model of experimental pulmonary metastasis, as the development of lung foci was statistically significant (P < 0.02; Kruskal-Wallis test) between all other rSV40 Tag-immunized mice (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Lung tumor focus burden in wild-type and Fcγ−/− immunized mice due to tumor challenge. Wild-type (WT) and FcγRIIB−/− and FcγRI/III−/− knockout mice were immunized with HBsAg or rSV40 Tag and challenged with the tumorigenic cell line mKSA. Upon staining lungs for the presence of tumor foci, tumor burden in each group was determined by the overall number of lung tumor foci. Columns, means of n mice per group challenged with mKSA; bars, standard errors; *, P < 0.02 (Kruskal-Wallis test).

Though FcγRI/III−/− mice have been reported to generate normal T-cell functions (30), CTLs are not expected to play a primary role in immunologic mechanisms against mKSA tumor cell challenge that lead to systemic tumor immunity (15). This hypothesis is further supported by previous results that indicate that an SV40 Tag-specific CTL response is undetectable in wild-type BALB/c mice immunized with rSV40 Tag (4). Thus, an FcγRI/III-mediated pathway plays some role in effector mechanisms that lead to the reduction of lung tumor foci in mKSA-challenged animals since the efficacy of a protective vaccine against the tumor-specific antigen SV40 Tag is reduced by mice deficient in FcγRI/III.

FcγRIIB-deficient mice mount a protective immune response to metastatic tumor challenge.

To again determine the level of immunologic protection against experimental pulmonary metastasis in this murine model, the role of the inhibitory molecule FcγRIIB in SV40 Tag antitumor activity was explored. FcγRIIB−/− mice were immunized with rSV40 Tag and challenged i.v. with mKSA tumorigenic cells. Tumor foci in the lungs of challenged mice were quantitated to determine the level of tumor immunity at 14 days post-tumor challenge.

The majority of FcγRIIB−/− mice immunized with rSV40 Tag did not succumb to mKSA tumor challenge. Only one of five mice exhibited lung tumor foci, which resulted in an overall focus average of 0.4 in rSV40 Tag mice (range from 0 to 2). These data differ from the HBsAg control-immunized control group where all mice developed lung tumor foci with an average of 9 foci and a range of 6 to 11. Representative images of lung tumor foci from FcγRIIB−/−-treated mice are shown in Fig. 2.

Lung focus values did not differ significantly between HBsAg-immunized mice (P < 0.05; Kruskal-Wallis test) (Fig. 3), indicating that overall immune functions were normal in FcγRIIB−/− and FcγRI/III−/− groups with respect to those in wild-type mice. These data, once more, underscore the importance of FcγRI/III effector populations during the course of protection from tumor challenge. Therefore, the genetic disruption of FcγRIIB protein does not appear to deter from the ability of mice to mount a protective immune response to experimental challenge with mKSA tumorigenic cells.

DISCUSSION

In this report, we demonstrate the requirement for expression of FcγRI/III on effector cells to achieve protection in a murine model of experimental pulmonary metastasis following rSV40 Tag immunization and challenge. FcγRI/III−/− knockout mice immunized with rSV40 Tag and challenged with the tumorigenic cell line mKSA succumbed to tumor challenge and developed lung tumor foci. These results differ from those FcγRIIB−/− mice that were protected from tumor challenge regardless of the absence of the inhibitory IgG receptor FcγRIIB. As wild-type and knockout strains of mice developed an overall IgG1 anti-SV40 Tag isotype distribution (data not shown) and comparable SV40 Tag antibody titers, a possible immunologic mechanism leading to protection in these animals likely involves Fc receptor-mediated ADCC by macrophages and/or NK cells. Similar findings have been observed utilizing murine systems of leukemia (38) and lymphoma (10, 32). Additional studies employing active immunization strategies towards melanoma have also implicated a direct role for FcγRI/III in antitumor activities. Clynes and colleagues (7) immunized wild-type and FcγR-deficient mice against the brown locus protein (gp75) and subsequently challenged animals i.v. with B16 melanoma cells. A significant reduction in lung metastases was observed in immunized wild-type mice compared to that in controls; however, no protective effect was observed in FcγR-deficient mice. Though the B- and T-cell immune responses developed normally in these animals and anti-gp75 antibody titers were comparable between all groups, tumor protection required the expression of FcγRs in mice. Additionally, in vitro assays indicated that NK cell-mediated (30) and macrophage-mediated ADCC (7) was abolished in FcγR−/− animals, suggesting that these two cell populations mediated B16 tumor immunity through FcγR effector pathways to various degrees.

The relative success of immunotherapy involving the passive administration of antibody and the ensuing role of Fc receptors in mediating tumor clearance has been realized in particular human cancers. For example, the FDA-approved anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody rituximab (Rituxan) is used to treat a number of B-cell abnormalities, including non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (6). Though the human immunologic response to rituximab has not been fully clarified, in vitro and in vivo murine studies (8, 9, 13) have demonstrated FcγR-driven ADCC with rituximab treatment. Yet, active immunization strategies may also represent an efficient prophylactic and/or therapeutic strategy to induce a long-lived and effective immune response (including memory cell recall) to specific targets expressed by human malignancies. With respect to our interpretation of required immune effector cells in this murine model of experimental pulmonary tumor challenge (15), vaccination strategies could be employed to induce the activation of antigen-specific CD4+ T cells. One resulting effect is that antigen-specific antibody is produced, and through a scenario that includes ADCC, FcγRI/III effector cells scavenge and destroy antibody/tumor cell complexes, particularly SV40 Tag-expressing cancers.

In our studies, mice deficient in FcγRIIB demonstrated protection from lung tumor foci as a result of mKSA tumor administration. From this observation, we conclude that a lack of FcγRIIB in mice did not hinder the ability of rSV40 Tag immunization to protect against systemic tumor immunity via an FcγR-mediated effector pathway. However, we cannot rule out the role of FcγRIIB in mediating protection by an indirect mechanism, perhaps through the modulation of FcγRIII that results in the regulation of ADCC activity (8). This remains plausible since tumor growth in control HBsAg-immunized FcγRIIB-deficient mice was less overall than in HBsAg-immunized FcγRI/III-deficient mice (Table 2). It is also of interest to note that BALB/c FcγRIIB−/− and FcγRI/III−/− strains developed anti-SV40 Tag antibody titers and isotype distribution similar to those previously reported by our group for wild-type mice (2, 15, 34). Though deficiencies in the inhibitory receptor FcγRIIB have been associated with both augmented and decreased antibody levels (1, 22, 31, 36), it remains possible that the SV40 Tag antibody response is not affected by the abrogation of this Fcγ receptor. Nonetheless, we demonstrate that FcγRIIB is not noticeably involved in immunologic mechanisms that lead to protection in this murine model of experimental pulmonary metastasis.

The required roles of FcγRI/III within this study further support the hypothesis that SV40 Tag antibody is required to achieve complete systemic tumor immunity within a prophylactic experimental challenge setting. Previous work by our group has shown that Th2 CD4+ T cells along with an anti-SV40 Tag antibody response were required for antitumor immune responses within the induction-phase immune response against an i.v. challenge with tumorigenic mKSA cells (15). If CD4+ T cells were depleted during the course of immunization, anti-SV40 Tag antibody was not produced as a result, and mice developed lung tumor foci. Additionally, in vitro assays demonstrated indirectly that ADCC activity was evident against mKSA by using peritoneal exudate cells and anti-SV40 Tag antibody from BALB/c mice (4). Activated Th2 CD4+ T cells might also be functioning to maintain low levels of the inhibitory receptor FcγRIIB on effector cells, as shown by one investigation (29), resulting in the increased activities of FcγRI/III-expressing immunologic cell populations. Though CD8+ T-cell function cannot be ruled out altogether in providing some level of tumor immunity, particularly when employing other active immunization modalities, such as plasmid DNA expressing SV40 Tag (2, 19, 25, 26), our previous studies indicated that depletion of CD8+ T cells during the course of rSV40 Tag immunization had no observable effect on the resultant tumor immunity (15). Therefore, we surmise that with regard to tumor immunity from mKSA challenge resulting from rSV40 Tag immunization, SV40 Tag specific antibody opsonizes the function of mKSA tumor cells and effector cells, such as macrophages and NK cells, via ADCC to mediate tumor lysis through expression of FcγRI/III.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grant RR-12317. D.B.L. is a Dean's Scholarship Award recipient.

We thank Allison M. Watts for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 15 November 2006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bergtold, A., D. D. Desai, A. Gavhane, and R. Clynes. 2005. Cell surface recycling of internalized antigen permits dendritic cell priming of B cells. Immunity 23:503-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bright, R. K., B. Beames, M. H. Shearer, and R. C. Kennedy. 1996. Protection against a lethal challenge with SV40-transformed cells by the direct injection of DNA-encoding SV40 large tumor antigen. Cancer Res. 56:1126-1130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bright, R. K., M. H. Shearer, and R. C. Kennedy. 1993. Comparison of the murine humoral immune response to recombinant simian virus 40 large tumor antigen: epitope specificity and idiotype expression. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 37:31-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bright, R. K., M. H. Shearer, and R. C. Kennedy. 1994. Immunization of BALB/c mice with recombinant simian virus 40 large tumor antigen induces antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity against simian virus 40-transformed cells. An antibody-based mechanism for tumor immunity. J. Immunol. 153:2064-2071. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Butel, J. S., and J. A. Lednicky. 1999. Cell and molecular biology of simian virus 40: implications for human infections and disease. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 91:119-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carter, P. J. 2006. Potent antibody therapeutics by design. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 6:343-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clynes, R., Y. Takechi, Y. Moroi, A. Houghton, and J. V. Ravetch. 1998. Fc receptors are required in passive and active immunity to melanoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:652-656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clynes, R. A., T. L. Towers, L. G. Presta, and J. V. Ravetch. 2000. Inhibitory Fc receptors modulate in vivo cytoxicity against tumor targets. Nat. Med. 6:443-446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dall'Ozzo, S., S. Tartas, G. Paintaud, G. Cartron, P. Colombat, P. Bardos, H. Watier, and G. Thibault. 2004. Rituximab-dependent cytotoxicity by natural killer cells: influence of FCGR3A polymorphism on the concentration-effect relationship. Cancer Res. 64:4664-4669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dyall, R., L. V. Vasovic, R. A. Clynes, and J. Nikolic-Zugic. 1999. Cellular requirements for the monoclonal antibody-mediated eradication of an established solid tumor. Eur. J. Immunol. 29:30-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gattinoni, L., D. J. Powell, Jr., S. A. Rosenberg, and N. P. Restifo. 2006. Adoptive immunotherapy for cancer: building on success. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 6:383-393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gazdar, A. F., J. S. Butel, and M. Carbone. 2002. SV40 and human tumours: myth, association or causality? Nat. Rev. Cancer 2:957-964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hernandez-Ilizaliturri, F. J., V. Jupudy, J. Ostberg, E. Oflazoglu, A. Huberman, E. Repasky, and M. S. Czuczman. 2003. Neutrophils contribute to the biological antitumor activity of rituximab in a non-Hodgkin's lymphoma severe combined immunodeficiency mouse model. Clin. Cancer Res. 9:5866-5873. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kennedy, R. C., and M. H. Shearer. 2003. A role for antibodies in tumor immunity. Int. Rev. Immunol. 22:141-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kennedy, R. C., M. H. Shearer, A. M. Watts, and R. K. Bright. 2003. CD4+ T lymphocytes play a critical role in antibody production and tumor immunity against simian virus 40 large tumor antigen. Cancer Res. 63:1040-1045. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kit, S., T. Kurimura, and D. R. Dubbs. 1969. Transplantable mouse tumor line induced by injection of SV40-transformed mouse kidney cells. Int. J. Cancer 4:384-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lanford, R. E. 1988. Expression of simian virus 40 T antigen in insect cells using a baculovirus expression vector. Virology 167:72-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lowe, D. B., M. H. Shearer, and R. C. Kennedy. 2006. DNA vaccines: successes and limitations in cancer and infectious disease. J. Cell. Biochem. 98:235-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lowe, D. B., M. H. Shearer, J. A. Tarbox, H. S. Kang, C. A. Jumper, R. K. Bright, and R. C. Kennedy. 2005. In vitro simian virus 40 large tumor antigen expression correlates with differential immune responses following DNA immunization. Virology 332:28-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGaha, T. L., B. Sorrentino, and J. V. Ravetch. 2005. Restoration of tolerance in lupus by targeted inhibitory receptor expression. Science 307:590-593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ostrand-Rosenberg, S. 2005. CD4+ T lymphocytes: a critical component of antitumor immunity. Cancer Investig. 23:413-419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qin, D., J. Wu, K. A. Vora, J. V. Ravetch, A. K. Szakal, T. Manser, and J. G. Tew. 2000. Fc gamma receptor IIB on follicular dendritic cells regulates the B cell recall response. J. Immunol. 164:6268-6275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ravetch, J. V., and S. Bolland. 2001. IgG Fc receptors. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 19:275-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ravetch, J. V., and L. L. Lanier. 2000. Immune inhibitory receptors. Science 290:84-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reimann, J., and R. Schirmbeck. 2004. DNA vaccines expressing antigens with a stress protein-capturing domain display enhanced immunogenicity. Immunol. Rev. 199:54-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schirmbeck, R., W. Bohm, and J. Reimann. 1996. DNA vaccination primes MHC class I-restricted, simian virus 40 large tumor antigen-specific CTL in H-2d mice that reject syngeneic tumors. J. Immunol. 157:3550-3558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shearer, M. H., R. K. Bright, and R. C. Kennedy. 1993. Comparison of humoral immune responses and tumor immunity in mice immunized with recombinant SV40 large tumor antigen and a monoclonal anti-idiotype. Cancer Res. 53:5734-5739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shearer, M. H., R. L. Lanford, and R. C. Kennedy. 1990. Monoclonal anti-idiotypic antibodies induce humoral immune responses specific for simian virus 40 large tumor antigen in mice. J. Immunol. 145:932-939. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Snapper, C. M., J. J. Hooley, U. Atasoy, F. D. Finkelman, and W. E. Paul. 1989. Differential regulation of murine B cell Fc gamma RII expression by CD4+ T helper subsets. J. Immunol. 143:2133-2141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takai, T., M. Li, D. Sylvestre, R. Clynes, and J. V. Ravetch. 1994. FcR gamma chain deletion results in pleiotrophic effector cell defects. Cell 76:519-529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takai, T., M. Ono, M. Hikida, H. Ohmori, and J. V. Ravetch. 1996. Augmented humoral and anaphylactic responses in Fc gamma RII-deficient mice. Nature 379:346-349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uchida, J., Y. Hamaguchi, J. A. Oliver, J. V. Ravetch, J. C. Poe, K. M. Haas, and T. F. Tedder. 2004. The innate mononuclear phagocyte network depletes B lymphocytes through Fc receptor-dependent mechanisms during anti-CD20 antibody immunotherapy. J. Exp. Med. 199:1659-1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Watts, A. M., and R. C. Kennedy. 1998. Quantitation of tumor foci in an experimental murine tumor model using computer-assisted video imaging. Anal. Biochem. 256:217-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Watts, A. M., M. H. Shearer, H. I. Pass, R. K. Bright, and R. C. Kennedy. 1999. Comparison of simian virus 40 large T antigen recombinant protein and DNA immunization in the induction of protective immunity from experimental pulmonary metastasis. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 47:343-351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Watts, A. M., M. H. Shearer, H. I. Pass, and R. C. Kennedy. 1997. Development of an experimental murine pulmonary metastasis model incorporating a viral encoded tumor specific antigen. J. Virol. Methods 69:93-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yada, A., S. Ebihara, K. Matsumura, S. Endo, T. Maeda, A. Nakamura, K. Akiyama, S. Aiba, and T. Takai. 2003. Accelerated antigen presentation and elicitation of humoral response in vivo by FcgammaRIIB- and FcgammaRI/III-mediated immune complex uptake. Cell. Immunol. 225:21-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yuasa, T., S. Kubo, T. Yoshino, A. Ujike, K. Matsumura, M. Ono, J. V. Ravetch, and T. Takai. 1999. Deletion of Fcgamma receptor IIB renders H-2(b) mice susceptible to collagen-induced arthritis. J. Exp. Med. 189:187-194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang, M., Z. Zhang, K. Garmestani, C. K. Goldman, J. V. Ravetch, M. W. Brechbiel, J. A. Carrasquillo, and T. A. Waldmann. 2004. Activating Fc receptors are required for antitumor efficacy of the antibodies directed toward CD25 in a murine model of adult T-cell leukemia. Cancer Res. 64:5825-5829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]