Abstract

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) entry into target cells requires the engagement of receptor and coreceptor by envelope glycoprotein (Env). Coreceptors CCR5 and CXCR4 are chemokine receptors that generate signals manifested as calcium fluxes in response to binding of the appropriate ligand. It has previously been shown that engagement of the coreceptors by HIV Env can also generate Ca2+ fluxing. Since the sensitivity and therefore the physiological consequence of signaling activation in target cells is not well understood, we addressed it by using a microscopy-based approach to measure Ca2+ levels in individual CD4+ T cells in response to low Env concentrations. Monomeric Env subunit gp120 and virion-bound Env were able to activate a signaling cascade that is qualitatively different from the one induced by chemokines. Env-mediated Ca2+ fluxing was coreceptor mediated, coreceptor specific, and CD4 dependent. Comparison of the observed virion-mediated Ca2+ fluxing with the exact number of viral particles revealed that the viral threshold necessary for coreceptor activation of signaling in CD4+ T cells was quite low, as few as two virions. These results indicate that the physiological levels of virion binding can activate signaling in CD4+ T cells in vivo and therefore might contribute to HIV-induced pathogenesis.

Entry of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) into target cells requires an interaction of envelope glycoprotein (Env) with CD4 and sequentially with one of the coreceptors, CXCR4 or CCR5 (24, 33, 41, 53, 61, 72). Interestingly, all three proteins have signaling functions in healthy, uninfected cells. CD4 provides a costimulatory signal in antigen-specific T-cell receptor-major histocompatibility complex II interaction in T cells (27). CXCR4 and CCR5 are chemokine receptors coupled to heterotrimeric Gαiβγ proteins. Activation of these G-protein coupled receptors (GPCR) by chemokine ligands initiates signal transduction pathways. These lead to elevation of intracellular free calcium, downregulation of cyclic AMP, activation of phospholipase C, phosphoinositide kinase-3, and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways (25, 32, 48, 57, 65). The signaling eventually results in upregulation of cytokine production, actin cytoskeleton reorganization, and chemotaxis.

Multiple groups have reported that HIV-1 Env and its subunit gp120 mediate similar changes in cells expressing CD4 and the corresponding coreceptor: Ca2+ fluxing (1, 7, 10, 47, 71), cyclic AMP downregulation (31), activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase MEK/ERK pathway (10, 56), rearrangements of actin cytoskeleton (10, 55), and chemotaxis (35). However, it is not known whether Env binding to its receptors mimics the chemokine-induced signal or creates a unique one and, more importantly, what physiological role it would have in HIV-caused pathogenesis. There are two schools of thought relating to the potential role of HIV envelope based signaling: one that emphasizes the importance of HIV-1 Env's “choice” to engage signaling molecules for its entry (1, 7, 31, 37, 58, 65) and another that suggests that Env-mediated signaling is dispensable for infection (3-5, 8). However, both views do agree on the existence of the Env-mediated signaling phenomenon. The key issue in this debate is the sensitivity of the signaling transduction system. If Env-mediated signaling requires high concentrations of gp120 that are rarely achieved in vivo, it seems unlikely that experimentally detected signaling would be physiologically relevant. In contrast, if low concentrations of gp120 can stimulate signaling, it seems likely that such interaction is highly specific, physiologically relevant, and better reflects the situation found in infected patients. We therefore decided to study Env-mediated signaling specificity, quality, and potency at low concentrations in individual cells.

We used the response of GPCR signaling, intracellular Ca2+ elevation, as an indicator of signal initiation. Observing the kinetics of this Ca2+ mobilization in individual cells allowed us to dissect the nature of the signal, involvement of CD4, and minimal Env concentration needed to activate signaling within individual primary unstimulated CD4+ T cells. This way, we indirectly addressed the question of the physiological relevance of Env-mediated signaling in primary target cells. Indeed, we found that approximately 10 pM of virion-bound gp120 was enough to initiate signaling. This concentration is in a range of gp120 values proposed to be present in the sera of infected patients (29), even though a much higher gp120 concentration is potentially achieved at the sites of infection, the secondary lymphoid organs (62). Translated to the level of an individual cell, we demonstrate signaling initiation with as little as two virions and an average of four virions. Our data reveal that the interaction of a few virions with T cells ex vivo can induce a unique signaling cascade in the absence of infection and in this way potentially contribute to the pathology of AIDS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines.

CHO-745/CycT CD4+, 745/CycT CD4+ CCR5+, and 745/CycT CD4+ CXCR4+ cell lines were kindly provided by Paul Bieniasz (The Rockefeller University, New York, NY). Cells were maintained in Iscove's modified Dulbecco medium (Bio-Whittaker/Cambrex Co., Walkersville, MD) containing penicillin G (200 U/ml), gentamicin (10 μg/ml), l-glutamine (0.3 μg/ml), 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), and 200 μg of G418/ml.

Primary CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell isolation.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells from healthy blood donors were isolated by Ficoll density gradient centrifugation. The peripheral blood mononuclear cell fraction was monocyte depleted by magnetically labeling cells with anti-CD14 monoclonal antibody (MAb)-coated microbeads and by applying the cell suspension onto a column within the magnetic cell-sorting separator according to the manufacturer's instructions (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). Labeled CD14+ cells were retained in the magnetized column, and the CD14− flowthrough was positively selected for CD4+ or CD8+ T cells by using anti-CD4 or anti-CD8 MAb-coated microbeads, respectively. Subsequently, CD4+ or CD8+ T cells retained in the magnetized column were eluted when the column was removed from the magnetic field. For some experiments, CD4+ T cells were isolated by negative selection using a CD4+ T-cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec), where untouched CD4+ T cells were collected as a flowthrough after the magnetic separation and all non-CD4+ T cells were retained in the column. Both ways of cell isolation yielded ∼98% CD4+ or CD8+ T-cell populations, as confirmed by flow cytometry. It is worth noting that there was no difference in the results obtained from CD4+ T cells isolated using either the positive or the negative selection method (data not shown). A total of 2 × 106 T cells/ml were cultivated in 15% FBS-RPMI 1640 (Bio-Whittaker/Cambrex) for 24 h without activation and then subjected to fluxing analysis. Work with human tissues was approved by Northwestern University (IRB 1754-002).

Reagents.

Stromal cell-derived factor 1α (SDF1α) was purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Recombinant monomeric HIVHXB envelope glycoprotein was kindly provided by Robert W. Doms (University of Pennsylvania). HIVBaL, AMD3100, and recombinant soluble CD4-183 (sCD4; 2-domain) (28) were obtained through the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, National Institutes of Health. The anti-p24 MAb AG3 was kindly provided by Jonathan Allan. Anti-hCCR5 and anti-hCXCR4 MAbs were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN), and phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-hCD4 antibody was obtained from Pharmingen, Inc. (San Diego, CA). Cy5 and fluorescein isothiocyanate anti-mouse secondary antibodies were purchased from Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories (West Grove, PA), and Alexa Fluor 350-phalloidin was from Invitrogen/Molecular Probes (Carlsbad, CA). Aminooxypentane (AOP)-RANTES was a gift from Oliver Hartley (Centre Medical Universitaire).

Virus stock.

Wild-type HIVMN and HIVADA strains made in H9 or Jurkat cells were CD45 depleted to eliminate microvesicles as described previously (69). Briefly, supernatants from stably infected H9 cells containing virus were incubated with anti-CD45-conjugated microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec), and the CD45+ fraction (microvesicles) was retained inside the magnetized column, allowing CD45− flowthrough (virus) to be collected. Viral preparations were then pelleted at 50,000 × g for 1 h at 4°C and resuspended in TNE buffer. Envelope glycoprotein on the virion surface remained functional, as shown by virus infectivity assays (26).

Flow cytometry.

A total of 5 × 105 cells were resuspended in 100 μl of 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubated with a 1:200 dilution of MAbs raised against hCD4 (phycoerythrin-conjugated RPA-T4 MAb), hCCR5, or hCXCR4 at 4°C for 30 min. For CCR5 and CXCR4 staining, cells were washed twice in 1% BSA, resuspended in 100 μl of ice-cold 1% BSA, and incubated with 1:400 dilution of fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-mouse immunoglobulin G for 30 min at 4°C. Finally, the cells were washed, resuspended in 200 μl of ice-cold 1% BSA, and analyzed by using FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson).

Single-cell calcium mobilization assay.

A total of 2 × 106 cells in 1 ml of RPMI (15% FBS) were loaded with 4 μM Fluo4-AM (Invitrogen Co., Carlsbad, CA). After 20 min of incubation at 37°C, cells were washed in PBS and additionally incubated for 10 min at 37°C in serum-free RPMI. Prior to microscopy, primary T cells were transferred to ΔT dishes (Bioptech, Inc., Butler, PA) with Cell-TAK (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA)-coated glass surface and allowed to attach for 15 min at 37°C in serum-free RPMI. Ca2+ measurements were performed on an Olympus IX70 DeltaVision API deconvolution microscope attached to a charge-coupled device camera in a temperature-controlled chamber at 37°C. The cells were imaged in real time at 488 nm. Random fields containing 15 to 20 cells were photographed every 10 s for 1 to 5 min prior to the addition of stimulus (chemokine, recombinant gp120, or the virus) and continued to be photographed for different lengths of time (indicated in the figure legend for each experiment). The nanostage of the DeltaVision microscope allowed simultaneous observation of more than one field. To detect background fluorescence changes, Fluo-4-loaded cells were observed every 10 s without stimulation for 8 min (CHO-745 cells) or 40 min (primary T cells).

For each experiment, the images were converted into a movie file that could be analyzed for fluorescence intensity in distinctive regions of interest using ImageJ software (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/docs/index.html). Ratios of green fluorescence at any time point (F) and initial fluorescence (F0) are directly proportional to the Ca2+ concentration changes (52). Ratios were plotted over time for regions of interest representing individual cells to obtain a graph showing relative changes in Ca2+ concentrations. Using this approach, we were able to detect the pattern of Ca2+ fluxing in individual cells, including the amplitude, frequency, and kinetics.

Virus quantification.

After Ca2+ fluxing experiments, cells were fixed directly in ΔT dishes while on the microscope with 3.7% formaldehyde in PIPES buffer (100 nM PIPES [pH 6.8], 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA) for 5 min. Cells were washed with PBS and blocked for 5 min with the blocking solution (0.1% Triton X-100, 1% BSA, and 0.01% sodium azide in 10% normal donkey serum). Anti-HIV p24 MAb was added at a 1:250 dilution to cells in blocking solution, followed by incubation for 30 min at room temperature. Cells were then washed and incubated with a 1:400 dilution of anti-mouse secondary Cy5 antibody in blocking solution for 20 min at room temperature. After a wash with PBS, cells were incubated with 1:250 Alexa Fluor 350-phalloidin for 20 min in PBS. After the final wash, the cells were imaged in three dimensions by using deconvolution microscopy. Eighteen individual image slices were taken as part of the z-series, from the top to the bottom of the cells, in order to create a volume projection. Image fluorescence intensities were normalized to the background of the control cells not infected with the virus but stained in the same manner.

Statistical analysis.

P values were calculated by using a two-tailed Student t test. Error bars represent the standard errors of the mean (SEM) unless otherwise noted. Statistical analysis was performed by using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) and GraphPad software.

Supplemental material.

Figure S1 in the supplemental material represents a time-lapse view of Fluo-4-loaded primary CD4+ T cells upon treatment with 10 ng of p24 HIVMN/ml. Cells were imaged every 10 s for 40 min, and virus was added after the first 5 min (30 frames). Quantification of the data shown in Table 3 is presented. Figure S2 in the supplemental material displays the Ca2+ response in CHO-745 CD4+ CCR5+ cells to the R5-tropic HIVADA strain, indicating the functionality of HIVADA Env.

TABLE 3.

Virion-mediated Ca2+ fluxing in CD4+ T cells

| Treatment | Avg percentage of cells fluxed ± SEMa | No. of cells fluxedb/total no. of cells tested |

|---|---|---|

| HIVMN (100 ng of p24/ml) | 27.5 ± 0.7 | 15/56 |

| HIVMN (10 ng of p24/ml) | 17.4 ± 0.2 | 80c/461 |

| HIVMN (1 ng of p24/ml) | 5.5 ± 1.1 | 4/63 |

| HIVMN (10 ng of p24/ml) + 10 μM AMD3100 | 5.7 ± 0.4 | 4/69 |

| HIVADA (10 ng of p24/ml) | 3.7 ± 1.9 | 6/162 |

| HIVMN (10 ng of p24/ml) + PTX (100 ng/ml) | 9.1 ± 2.3 | 12/134 |

| SDF1α + PTXd (100 ng/ml) | 2.03 ± 1.27 | 2/108 |

Data represent average values from ≥3 independent experiments.

During 35-min interval upon virus addition.

The fluxing kinetics in these cells are shown in Fig. 6.

PTX, pertussis toxin.

RESULTS

Monomeric gp120 induces coreceptor-specific Ca2+ mobilization.

To detect HIV Env-initiated signaling cascades upon receptor engagement, we decided to monitor the changes in the secondary messenger, intracellular free Ca2+. To this end, Ca2+ concentration fluctuations within individual cells were visualized by real-time microscopy. For Ca2+ detection, cells were loaded with fluorescent Ca2+ indicator Fluo-4. The fluorescence intensity of Fluo-4 increases rapidly after it binds to free Ca2+ ions (52, 70) and is therefore directly proportional to the free Ca2+ concentration changes. Prior to all of the signaling experiments, we determined the baseline calcium fluctuations to distinguish the background changes from the actual Ca2+ flux. In this case, we imaged individual CHO-745 cells in the absence of any stimulation for 8 min. The free Ca2+ concentration in these cells fluctuated within a 1.5-fold range in the absence of stimuli and was used as a threshold value (Fig. 1A). Any signal greater than this threshold was scored as positive.

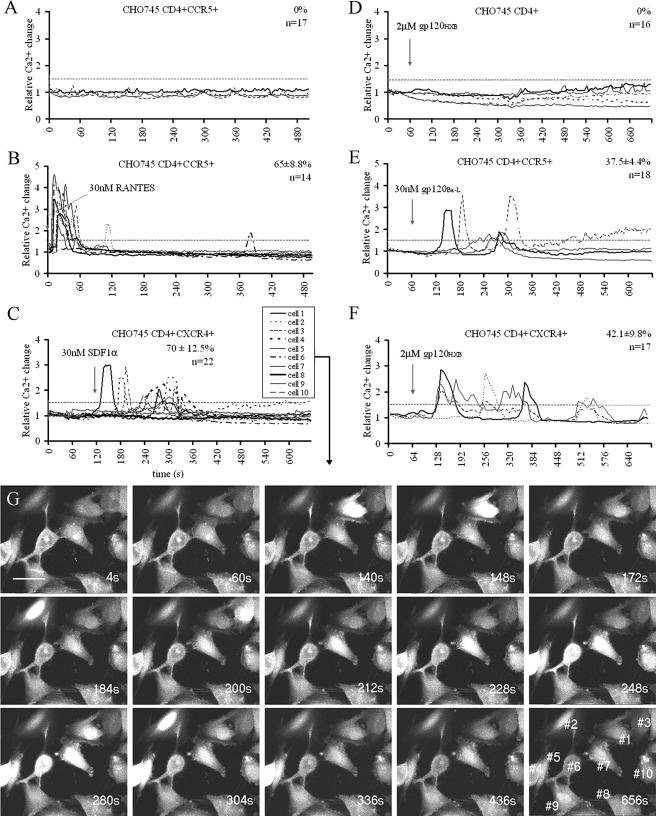

FIG. 1.

Specificity of gp120-mediated Ca2+ fluxing in CHO-745 cell lines. (A) Untreated CHO-745 CD4+ CCR5+ cells imaged for 500 s under the microscope to obtain the background Ca2+ fluctuation threshold, as described in Materials and Methods. The fluxing threshold was set to 1.5-fold, as indicated on the graphs. In all experiments, lines represent individual cells and are representatives of n, the total number of cells tested from a minimum of two experiments. The percentage value refers to the relative number of the cells fluxed ± the SEM. (B to F) CHO745 cell lines as indicated on the graphs treated with the indicated stimulus at the time point marked by an arrow. (G) Time-lapse images of CHO-745 CD4+ CXCR4+ cells from graph C. Scale bar, 17 μm. The numbers of the cells corresponding to the fluxing in response to SDF1α (panel C) are shown in the last panel.

To initiate this analysis, we chose the three previously characterized CHO-745 cell lines expressing human CD4+, CD4+ CCR5+, or CD4+ CXCR4+. These cell lines expressing different combinations of receptor and coreceptor served as an analytical tool, allowing us to compare the requirements for Env-mediated versus chemokine-mediated signaling. The CHO-745 cell lines showed the anticipated response when exposed to the appropriate chemokine. The specific ligand for CXCR4 is SDF1α, and one of the ligands specific to CCR5 is chemokine regulated on activation, normal T-cell expressed and secreted (RANTES). CHO-745 CD4+ CCR5+ cells responded rapidly to the addition of 30 nM AOP-RANTES (Fig. 1B), and CD4+ CXCR4+ cells responded rapidly to 30 nM SDF1α (Fig. 1C). CHO-745 CD4+ cells did not respond to either AOP-RANTES or SDF1α, as expected. In addition, no signaling was detected in CD4+ coreceptor expressing CHO-745 cells if treated with the nonmatching chemokine (data not shown). Ca2+ fluxing in response to the chemokines was heterogeneous overall. Rapid initial Ca2+ fluxing was observed as soon as 10 s in some cells, whereas the response was delayed in others. Often the same cell fluxed more than once in transient peaks (Fig. 1B and C), whereas some cells never responded during the period of analysis.

After establishing the pattern of CHO cell signaling with chemokines, we tested their responsiveness to recombinant monomeric gp120. We exposed three CHO-745 cell lines to R5-tropic gp120BaL or X4-tropic gp120HXB. By combining different coreceptors with gp120 of two different tropisms, we could get an insight into the specificity of the observed cellular response and test the importance of CD4 alone in signaling initiation.

We found that CHO-745 cells responded to gp120 after 1 to 2 min, which was delayed compared to the chemokine-induced signal. CHO-745 CD4+ CCR5+ but not CD4+ CXCR4+ cells responded to 30 nM R5-tropic gp120BaL (Fig. 1E). CHO-745 CD4+ CXCR4+ cells mobilized Ca2+ in response to the matching X4-tropic gp120HXB (Fig. 1F) but required a higher gp120 concentration. No response was observed until a 2 μM concentration was used. At the same time, single positive CHO-745 CD4+ cells did not generate Ca2+ signal after treatment with as much as 2 μM gp120HXB (Fig. 1D). Altogether, these results implied that the Ca2+ signaling we were detecting upon gp120 addition was coreceptor specific and solely coreceptor mediated. However, it is worth noting that the effective stimulatory gp120 concentration in CHO cell lines is superphysiological considering the potential in vivo gp120 levels (38).

Gp120-mediated Ca2+ fluxing in primary unstimulated CD4+ T cells is coreceptor mediated.

To test the coreceptor specificity in a more physiologically relevant environment, we focused on the requirements for gp120-mediated signaling ex vivo in primary unstimulated CD4+ T cells. This heterogeneous cell population expresses CXCR4 (12, 51) but not CCR5, therefore representing an ideal system for examining coreceptor specificity in gp120-mediated signaling.

Again, the background Ca2+ fluctuation was determined by monitoring untreated CD4+ T cells for 40 min, which maintained Ca2+ levels within a twofold range (Fig. 2A). Only 2.5% ± 0.5% cells elevated the Ca2+ level above this threshold in the absence of stimuli. SDF1α treatment caused a rapid Ca2+ fluxing in 34.5% ± 1.8% cells (Fig. 2B and Table 1) . The response in these cells was consistent with results obtained from the CHO-745 CD4+ CXCR4+ cell line (compare Fig. 1C and Fig. 2B). The first T cells responded within 10 s, often in more than one transient peak, where the calcium level stayed elevated for an average of 1.1 ± 0.1 min per peak. Higher SDF1α concentrations (up to 500 nM) increased the number of Ca2+ fluxes per cell but could not increase either the relative number of responsive cells or the amplitude of the response (data not shown).

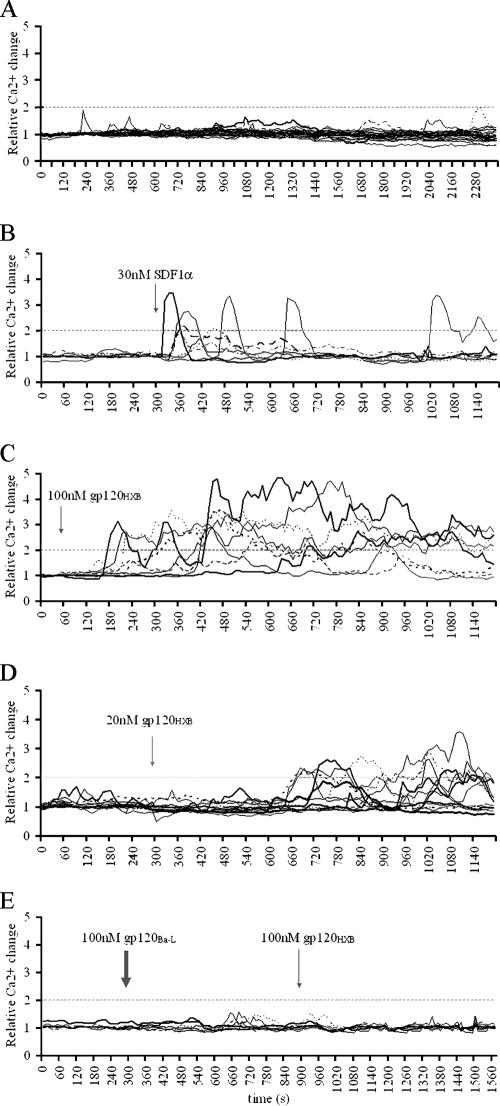

FIG. 2.

Specificity of gp120-mediated Ca2+ fluxing in primary unstimulated CD4+ T cells. (A) Primary CD4+ T cells imaged for 40 min without any stimulation to obtain background Ca2+ fluctuations. This twofold threshold is indicated on all graphs. Each line represents an individual cell. (B to D) CD4+ T cells treated with 30 nM SDF1α (B), 100 nM gp120HXB (C), or 20 nM gp120HXB (D) at the time points indicated by the arrows. (E) Cells treated with 100 nM gp120BaL (thick arrow) and subsequently with 100 nM gp120HXB (thin arrow). All figures are representative of a minimum of three experiments. A quantification of these data is also shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Monomeric gp120-mediated Ca2+ fluxing in CD4+ T cells

| Treatment | Avg percentage of cells fluxed ± SEMa | No. of cells fluxedb/total no. of cells tested |

|---|---|---|

| gp120HXB (20 nM) | 25.2 ± 1.7 | 27/103 |

| gp120HXB (100 nM) | 35.2 ± 1.2 | 66/188 |

| gp120HXB (200 nM) | 44 ± 3.2 | 33/75 |

| gp120HXB (100 nM) + AMD3100 (10 μM) | 7.8 ± 1.5 | 6/75 |

| gp120BaL (100 nM) | 3.1 ± 0.9 | 5/130 |

| gp120BaL (100 nM) + gp120HXB (100 nM) | 5.5 ± 5.5 | 1/17 |

| SDF1α (30 nM) | 34.5 ± 1.8 | 30/85 |

| None (control)c | 2.5 ± 0.5 | 2/80 |

Data represent average values from ≥3 independent experiments.

During 15-min interval upon stimulus addition.

Untreated cells observed for 40 min.

We next sought to determine whether and under which conditions unstimulated primary CD4+ T cells respond to recombinant monomeric X4-tropic gp120HXB. Indeed, T cells did mobilize intracellular Ca2+ after gp120HXB treatment (Table 1). The calcium level remained elevated for a maximum 14 min per peak, with an average of 4.6 ± 0.8 min per peak, which was significantly longer than the peak caused by SDF1α (P < 0.01). At 100 nM gp120HXB, there was a 2- to 3-min lag phase before any flux was detected (Fig. 2C). This lag phase was detected even at higher gp120 concentrations and was prolonged when lower gp120HXB concentrations were used. For example, with 20 nM gp120HXB, the lag phase ranged from 5 to 7 min (Fig. 2D), and a significantly lower percentage of cells responded (Table 1). At less than 20 nM gp120HXB we could not detect changes in intracellular Ca2+ concentrations above the twofold threshold within 15 min of addition. Therefore, the unstimulated CD4+ T cells were 100-fold more sensitive in their response to X4-tropic gp120 than the CHO-745 CD4+ CXCR4+ cells described above. Blocking CXCR4 signaling ability with a small inhibitory molecule, AMD3100 (63), allowed us to confirm the coreceptor specificity of the observed Ca2+ mobilization. The values shown in Table 1 indicate that 10 μM AMD3100 significantly abrogated gp120HXB-mediated cell signaling initiation (P < 0.001). Moreover, 100 nM R5-tropic gp120BaL could not cause Ca2+ fluxing in tested CD4+ T cells (Table 1), where the CCR5 surface expression was <1.2% (data not shown). Thus, the observed signaling was mediated through the cognate coreceptor.

CD4 is necessary for gp120-mediated Ca2+ fluxing in primary unstimulated CD4+ T cells.

The results described above questioned the role of CD4 in gp120-mediated Ca2+ signaling, since the lack of response to R5-tropic gp120BaL was observed in primary CD4+ T cells (Table 1) and to gp120HXB in single positive CHO-745 CD4+ cells (Fig. 1D). These data suggested that CD4 binding alone was insufficient for Ca2+ mobilization.

Interestingly, R5-tropic and X4-tropic gp120 appeared to compete for CD4 binding. The pretreatment of primary CD4+ T cells with 100 nM R5-tropic gp120BaL abolished signaling by 100 nM X4-tropic gp120HXB (Fig. 2E). This suggested a role for CD4-gp120 binding in Ca2+ signaling, even though the signal was mediated through CXCR4. gp120 probably required CD4 binding prior to CXCR4 engagement, a view consistent with the previous results showing that CD4 engagement was required for V3 loop exposure in gp120 and a subsequent interaction with coreceptor (24, 41, 72).

To test CXCR4 signaling in a CD4-free environment, we used primary CD8+ CD4− T cells that express CXCR4 at comparable levels to primary CD4+ T cells (Fig. 3A). CD8+ T cells were responsive to SDF1α in a fashion similar to CD4+ T cells. Most of the cells responded rapidly, in transient peaks (Fig. 3B and Table 2). CD8+ T cells were, however, unable to elevate Ca2+ upon addition of up to 2 μM gp120HXB, even though the same cells responded to SDF1α (Fig. 3C). Nevertheless, when we provided CD4 in trans by adding soluble CD4 (sCD4) to the cells prior to gp120HXB addition, CD8+ T cells elevated Ca2+ after a 1-min lag (Fig. 4B).

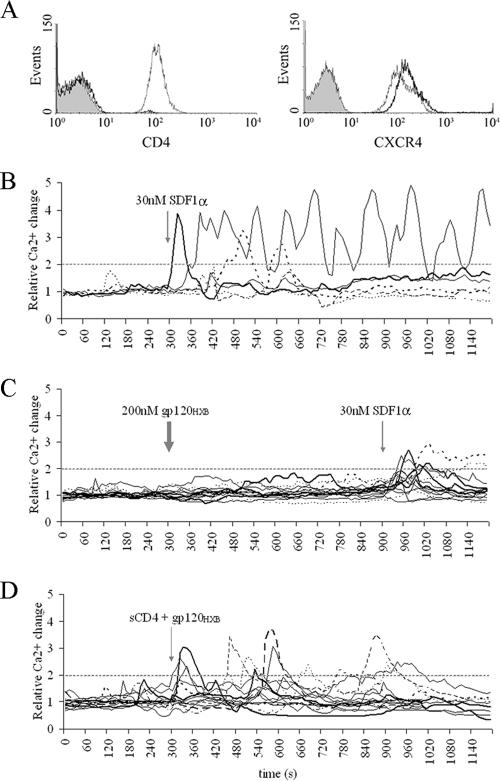

FIG. 3.

CD8+ T-cell response to monomeric gp120. (A) Flow cytometry of primary unstimulated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells 24 h after isolation from peripheral blood. Plots show the expression levels of CD4 or CXCR4 in CD4+ T cells (thin line) and CD8+ T cells (thick line), with isotype control antibodies (gray histogram). (B and C) CD8+ T cells treated with 30 nM SDF1α (B) or 200 nM gp120HXB (thick arrow) and subsequently with 30 nM SDF1α (thin arrow) (C). (D) 200 nM gp120HXB preincubated with 500 nM sCD4 for 5 min at 37°C prior to addition onto CD8+ T cells. All figures are representative of a minimum of two experiments. Each line represents an individual cell. A quantification of these data is also shown in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Selective effect of sCD4 on gp120-mediated Ca2+ fluxing in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells

| Cell type and treatment | Avg percentage of cells fluxed ± SEMa | No. of cells fluxedb/total no. of cells tested |

|---|---|---|

| CD4+ T cells | ||

| gp120HXB (200 nM)c | 44 ± 3.2 | 33/75 |

| sCD4 + gp120HXB (1:2)d | 32.5 ± 3.5 | 23/67 |

| sCD4 + gp120HXB (1:1) | 21.5 ± 2 | 16/76 |

| sCD4 + gp120HXB (5:2) | 6.6 ± 1.1 | 7/112 |

| sCD4 (200 nM) | 5.5 ± 2.6 | 2/27 |

| sCD4 + SDF1α (5:2) | 35.1 ± 2.3 | 44/126 |

| CD8+ T cells | ||

| gp120HXB (200 nM) | 3.1 ± 0.8 | 3/96 |

| sCD4 + gp120HXB (5:2) | 16.6 ± 1.6e | 20/117 |

| SDF1α (30 nM) | 35.9 ± 3 | 16/42 |

Data represent average values from ≥2 independent experiments.

During 15-min interval upon stimulus addition. The fluxing kinetics in these cells are shown in Fig. 4.

These data are also shown in Table 1.

The ratios given in parentheses represent the molar ratio relative to the given concentration of gp120 or sCD4.

P value of <0.001 versus gp120HXB effect in CD8+ T cells.

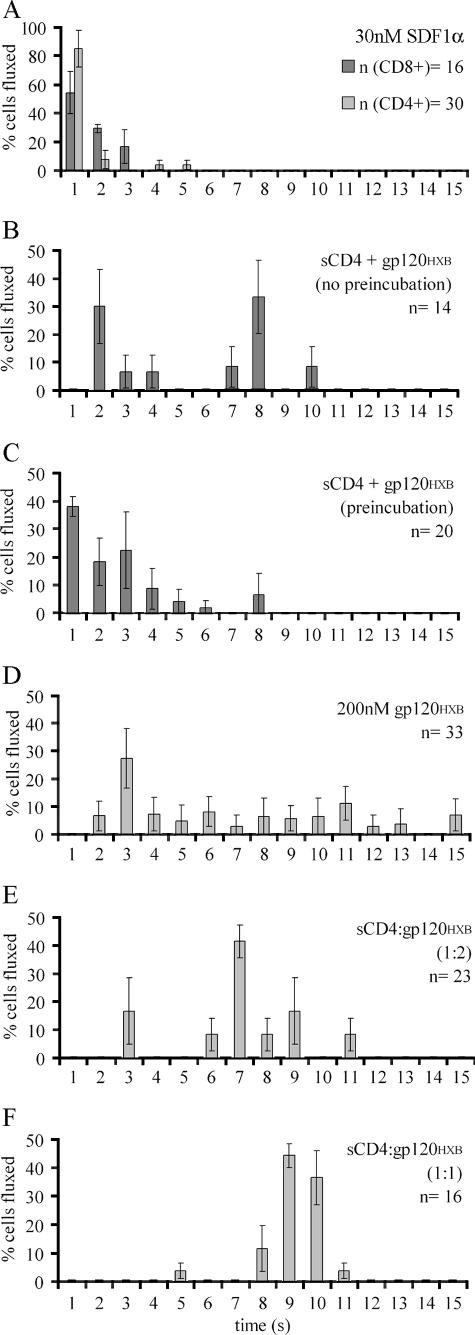

FIG. 4.

sCD4 altered fluxing kinetics in T cells. (A) Relative numbers of fluxing CD4+ or CD8+ T cells (n) plotted over the time it took them to elevate Ca2+ above the twofold threshold upon the addition of 30 nM SDF1α. (B) Fluxing kinetics of CD8+ T cells in response to 200 nM sCD4, subsequently treated with 200 nM gp120HXB (1:1 molar ratio). (C) Fluxing kinetics of CD8+ T cells treated with preincubated sCD4-gp120HXB complex in 5:2 molar ratio. (D to F) Fluxing kinetics of CD4+ T cells in response to 200 nM gp120HXB (D), preincubated sCD4-gp120HXB complex in a 1:2 molar ratio (E), or preincubated sCD4-gp120HXB complex in a 1:1 molar ratio (F). All graphs show the average values ± the standard deviation obtained only from fluxing cells (n). Quantitative data from these experiments are also shown in Table 2.

In contrast, no lag phase in Ca2+ mobilization was detected when gp120HXB and sCD4 were preincubated for 5 min at 37°C and then added to CD8+ T cells (Fig. 3D and 4C). Thus, prebinding of gp120 to sCD4 appeared to remove a kinetic step allowing signaling to occur on the same timescale as that of chemokine SDF1α (Fig. 3D). The observation that the prebinding of gp120 and sCD4 removes the lag before signaling suggests that the observed lag was not due to the slower diffusion rate of gp120 compared to SDF1α. It rather reflects the time for gp120 to bind CD4, change its conformation to expose the V3 loop, engage the coreceptor, and subsequently initiate Ca2+ flux. It is worth noting that sCD4 did not alter normal SDF1α-mediated activation of CXCR4 signaling (Table 2).

In contrast to CD8+ T cells, treatment of CD4+ T cells with gp120HXB preincubated with sCD4 failed to accelerate signaling initiation. Actually, sCD4 had an inhibitory effect on the kinetics of Ca2+ signaling. As shown in Fig. 4E, with a 1:2 molar ratio of sCD4 to gp120, the lag phase increased from 2 to 3 min up to 3 to 6 min, and with 1:1 molar ratio it increased up to 5 to 8 min. Increasing concentrations of sCD4 prolonged the lag phase and decreased the number of the responding cells until the total abrogation of the signal (Table 2). Therefore, the soluble gp120-sCD4 complex behaved differently in the presence of transmembrane CD4 on the target cells.

Low levels of X4-tropic virions mediate Ca2+ fluxing in primary unstimulated CD4+ T cells.

The results presented above reveal that CD4+ T cells respond to monomeric X4-tropic gp120 and that the generated Ca2+ signal is CXCR4-mediated but dependent on CD4 binding. However, in its native form, virion-bound Env is a trimer composed of three gp120 exterior glycoproteins and three transmembrane gp41 glycoproteins (22, 74). Therefore, the ability of virion-bound, trimeric, X4-tropic gp120MN to activate CXCR4-mediated Ca2+ fluxing in CD4+ T cells was determined. In all of the following experiments, T cells were exposed to replication-competent HIVMN virions depleted of CD45 (69). This viral preparation contained a highly active homogeneous stock, wherein general debris and microvesicles have been removed to avoid nonspecific artifacts in signaling (14).

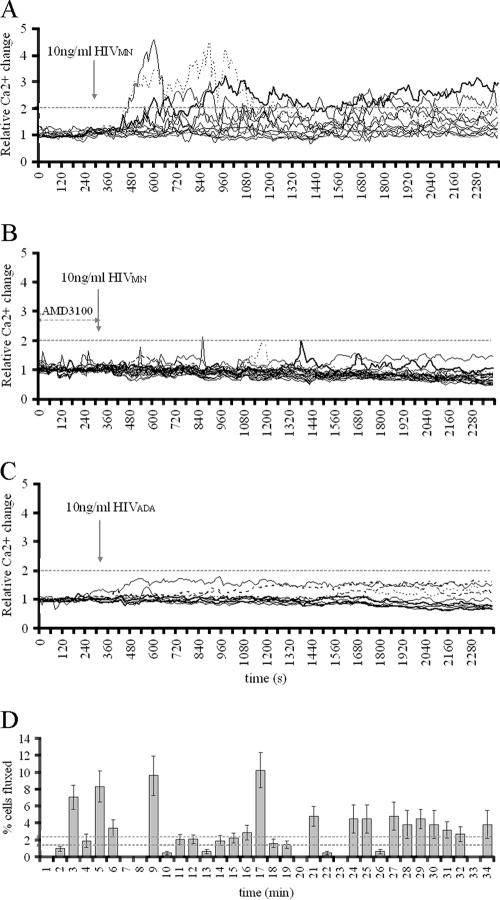

The response of CD4+ T cells to HIVMN was dose dependent. The number of cells that elevated the Ca2+ above the twofold threshold within the first 35 min positively correlated with the HIVMN p24 concentration (Table 3). The lowest p24 concentration that stimulated fluxing was 10 ng of p24 HIVMN/ml (Fig. 5A and Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), which led to fluxing in 17.4% ± 0.2% cells.

FIG. 5.

Virion-mediated Ca2+ fluxing in CD4+ T cells. (A) CD4+ T cells treated with 10 ng of p24 HIVMN/ml at the time point indicated by an arrow. The graph represents data obtained from the signaling movie shown in the supplemental material. (B) Cells preincubated with 10 μM AMD3100 for 25 min treated with 10 ng of p24 HIVMN/ml. (C) CD4+ T cells treated with 10 ng of p24 HIVADA/ml. (D) Kinetics of CD4+ T cell response to HIVMN. Shown are the relative numbers of 80 cells that fluxed upon the addition of 10 ng of p24 HIVMN/ml, distributed by the time necessary to elevate the Ca2+ level above twofold threshold. The values are averages of 26 experiments ± the SEM. Dotted lines (2.5% ± 0.5%) represent the cutoff for cells that nonspecifically fluxed in threshold determination experiments (Table 1). Quantitative data from all graphs are also shown in Table 3.

Coreceptor specificity in virion-mediated fluxing is shown in Fig. 5B, wherein the pretreatment of primary CD4+ T cells with CXCR4 inhibitor AMD3100 diminished Ca2+ signaling. While 10 ng of p24 HIVMN/ml activated Ca2+ fluxing in T cells, the same concentration of R5-tropic HIVADA failed to induce any signals over background levels (Fig. 5C). The results obtained from CHO-745 cells treated with virions also implied coreceptor specificity in fluxing: 10 ng of p24 HIVADA/ml elevated Ca2+ in 20.4 ± 1.8% CHO-745 CD4+ CCR5+ cells (Fig. S2 in the supplemental material), and yet HIVMN did not activate fluxing in a single CHO-745 CD4+ CCR5+ cell of 22 tested (data not shown). Thus, virion-mediated signaling requires an Env-coreceptor match, reflecting the results obtained with monomeric gp120.

The pattern of HIVMN-induced Ca2+ elevation resembled that observed for monomeric gp120HXB. Coreceptor response to 10 ng of p24 HIVMN/ml was at least three minutes delayed (Fig. 5A and D), whereas some cells took longer than 3 min to activate signaling (Fig. 5D). The average length of Ca2+ peaks was 3.72 ± 0.9 min and was not statistically different from the length of monomeric gp120HXB-mediated Ca2+ flux. The high heterogeneity in kinetics and pattern of cellular response to the virus is likely due to the kinetics and frequency of viral attachment events to target cells.

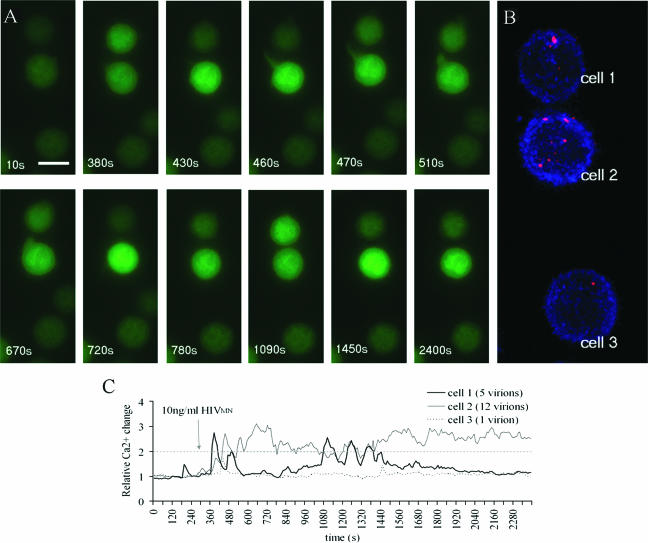

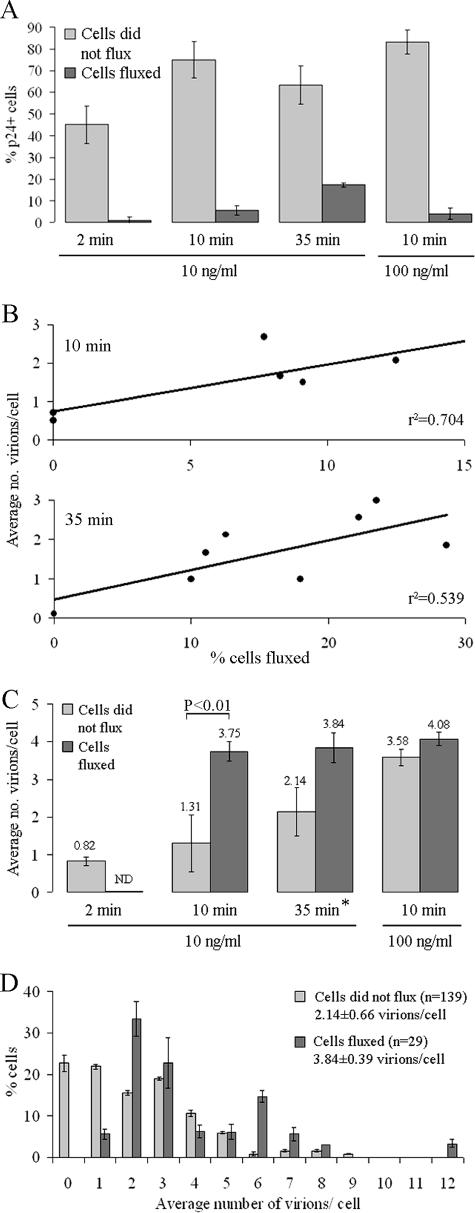

To gain insight into how virion binding correlates to the Ca2+ fluxing pattern, the number of viral particles bound to each T cell were counted. After the fluxing experiments, the cells were fixed and stained for HIV p24 capsid protein. The fluorescent p24 signal was normalized to the control virus-free cells stained for p24, and each round dot above the background pixel threshold was counted as a single virion (Fig. 6). In all cases, virions were randomly dispersed on the surfaces of target cells (Fig. 6B). It appears that Ca2+ had been mobilized only in a subset of p24+ cells (Fig. 7A), as observed in the T-cell responses to SDF1α and monomeric gp120 (Table 1). Importantly, we found that 99% ± 0.7% of cells that did flux had detectable p24 signal on their plasma membranes. The majority of p24+ cells did not flux (Fig. 7A), but the portion of p24+ fluxing cells increased over time (Fig. 7A). For instance, between 10 and 35 min the percentage of fluxing p24+ cells increased from 5.3% ± 0.6% to 17.4% ± 0.2% in cells treated with 10 ng of p24/ml and from 4.1% ± 0.6% to 27.5% ± 0.7% in cells treated with 100 ng of p24/ml (Fig. 7A and Table 3). Among individual experiments, a positive correlation between the frequency of Ca2+ fluxing and the average virion number per cell was noticed 10 min after the HIVMN treatment. This correlation was somewhat decreased by 35 min (Fig. 7B), possibly due to responses to previously bound virus or the ongoing release or turnover of virus on cell surface.

FIG. 6.

Binding of HIVMN virions to individual primary CD4+ T cells. (A) Example of virion-binding experiment. Fluo-4-loaded cells were observed under a microscope (×100) every 10 s for 40 min and treated with 10 ng of p24 HIVMN/ml after the first 300 s. Scale bar, 7 μm. (B) After 40 min of the signaling experiment, the cells were fixed and stained for HIV-1 p24 (red) and actin (blue). Eighteen images from the top to the bottom of the cells were digitally overlapped to give one image, a volume projection of the z-series. Therefore, all of the virions were found on the cell surface. (C) Red p24 signals were counted, and the numbers correlated to the pattern of Ca2+ fluxing in the same cells. Relative Ca2+ concentration changes were plotted over time.

FIG. 7.

Virion distribution on fluxing versus nonfluxing T cells. (A) Percentage of cells that had the virus (p24 signal) on their surface 2, 10, or 35 min upon addition of 10 or 100 ng of p24 HIVMN/ml. The upper portions of the bars represent the percentage of p24-positive cells that also had fluxed. Values were averaged from a minimum of four experiments ± the SEM. (B) Positive correlation between the percentage of cells fluxed and average number of virions per cell in individual experiments. Each dot represents a single experiment. The plots show the correlation 10 or 35 min upon the addition of 10 ng of p24 HIVMN/ml. r2, coefficient of determination. (C) Data show the average virion numbers found on cells that fluxed versus cells that did not 2, 10, or 35 min after treatment with 10 or 100 ng of p24 HIVMN/ml. Shown are the average values from nine experiments ± the SEM. ND, not determined. *, Data also represented in graph B. (D) Distribution of virion numbers attached to individual cells that fluxed versus cells that did not flux in response to 10 ng of HIVMN/ml during a 35-min interval. The average of nine experiments ± the SEM is given.

Figure 7C represents the quantification of HIV p24 signal on cells that fluxed versus ones that did not flux upon different HIVMN treatments. A time- and concentration-dependent increase in average virion numbers on cells that did not flux was observed. In contrast, cells that did flux had an average of four virions attached, even under different experimental conditions (Fig. 7C). A statistical difference in the number of virions bound to fluxing versus nonfluxing T cells can be seen 10 min after viral addition. This difference is lost 35 min into the treatment, since now more viruses landed on nonfluxing cells. Interestingly, even though there was no difference in the average virion numbers bound to the two cell groups after 35 min (Fig. 7C), the distribution of virions on responding and nonresponding cells is certainly different (Fig. 7D). We detect 1 to 12 virions bound to an individual responsive cell. As mentioned above, these cells were always found with at least one viral particle, but most often with two or three. However, cells that did not elevate Ca2+ after the same HIVMN treatment were often found with no virus, and no obvious preference for the distribution of virion particles among cells was observed.

DISCUSSION

How CD4+ T cells respond to binding of HIV envelope glycoprotein is a controversial issue. We sought to determine whether low numbers of free monomeric (gp120m) and virion-associated trimeric gp120 (Env) could be recognized by CD4+ T cells through signal transduction pathways initiated by signaling molecules CD4 and CXCR4, which serve as receptors in X4-tropic HIV entry (25, 32, 48, 57, 65). As a marker for the initiation of signaling, we chose to monitor the oscillations of a secondary messenger, free intracellular Ca2+. Detecting Ca2+ changes by real-time microscopy allowed the kinetics and requirements for activation of Env-mediated signaling to be studied in individual primary unstimulated CD4+ T cells. This approach enabled the sensitive detection of signaling at extremely low concentrations of X4-tropic Env.

Our data showed that both gp120m and Env were able to induce signaling in cells expressing CD4 and a coreceptor. gp120m- and Env-mediated coreceptor-specific Ca2+ fluxing was only observed when the matching coreceptor responded to R5-tropic or X4-tropic gp120. The engagement of CD4 alone could not mobilize Ca2+ within our detection range, which suggested that Ca2+ signal was being mediated solely through the coreceptor. This was confirmed because signaling mediated by X4-tropic gp120 was sensitive to CXCR4 inhibitor AMD3100. In addition, we showed that coreceptor-mediated Ca2+ fluxing upon HIV gp120 binding was CD4 dependent. Primary CD8+ CD4− CXCR4+ T cells were observed to elevate Ca2+ in response to gp120m only in the presence of soluble CD4. This was in agreement with previous reports that gp120 activates the coreceptor and leads to Ca2+ fluxing and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway signaling only upon previous gp120-CD4 interaction (56, 71). However, even though CD4 was required, it did not have to be on the cells surface, strengthening the conclusion that signaling was coreceptor mediated.

The pattern of Ca2+ mobilization initiated by both gp120m and Env was qualitatively different from that induced by chemokines. Chemokines AOP-RANTES and SDF1α caused rapid, transient Ca2+ peaks through CCR5 or CXCR4, respectively. In contrast, a delayed, sustained plateau of Ca2+ was a consequence of gp120m and Env treatments. This phenomenon was independent of gp120 tropism and concentration. Also, when endogenous CD4 was absent, as in primary CD8+ T cells, a gp120-sCD4 complex mobilized Ca2+ through CXCR4 in a similar fashion as SDF1α did, with multiple transient peaks. This finding suggested that the signal generated by a cell-associated gp120-CD4-CXCR4 complex was qualitatively different from the chemokine signaling. That is, when CD4 was present in the membrane of target cells along with the matching coreceptor, gp120 elicited a unique extended pattern of Ca2+ elevation. This is reasonable given the fact that CD4 is a signaling molecule that is capable of transmitting signals upon gp120 binding (65). Alternatively, the simultaneous engagement of CD4 and coreceptor may prevent the normal endocytosis of the chemokine receptor. Endocytosis and subsequent acidification of a GPCR causes the ligand to be released ending the signaling. Engaging CD4 and chemokine receptor simultaneously may alter this process, leading to a sustained signal. This may be especially important in the context of virion-associated envelopes where multiple molecules are likely simultaneously engaged. The importance of this unique signaling pattern might be related to recent findings that T and B cells are able to differentiate the quality of outside stimuli even at the level of a secondary messenger. Different Ca2+ elevation patterns, including the amplitude, frequency, and the length of elevation can lead to the activation of different transcription factors and therefore to distinct cellular responses (13, 15, 18, 19, 45, 67, 73). However, since we did not test any of the downstream effectors of CD4 and GPCR signaling, CD4-CXCR4 synergy in gp120-mediated signaling requires future investigation.

The presence of a lag phase in coreceptor activation was an additional difference between the effects of chemokine and gp120 glycoprotein. Unlike the rapid SDF1α-mediated calcium mobilization, there was a statistically significant delay in CXCR4 activation by both gp120m and Env. The earliest CXCR4 activation events occurred 2 to 3 min after the gp120 treatment, a finding consistent with other published data on the existence of a lag phase in HIV-1 fusion (17, 20, 36, 50, 54, 59). A likely explanation is that the lag interval represents the time necessary for gp120 attachment to CD4, conformational changes to expose the V3 loop, and a subsequent coreceptor engagement (24, 33, 41, 53, 61, 72). Consistent with that, no delay was detected in CD8+ T cells response to preincubated complex of gp120m and sCD4, suggesting that coreceptor engagement and signaling are relatively fast, similar to the SDF1α effect. Our assumption is in agreement with the work of LaBranche et al. (40) and Gallo et al. (26), who showed a reduced time lag in the fusion of CD4-independent gp120 mutant compared to the wild type. In addition, data obtained from prior temperature-arrested fusion state studies indicate that CD4 engagement is the first rate-limiting step in viral fusion (30, 49).

It is worth noting that a 3-min lag in coreceptor activation with gp120m was present at concentrations above and around its Kd for CXCR4 binding (∼200 nM) (9). Nevertheless, a 10-fold-lower gp120m concentration caused slower coreceptor engagement kinetics in a reduced number of CD4+ T cells. A similar effect was seen as a result of soluble CD4 on gp120-mediated signaling in CD4+ T cells where sCD4 acted in an inhibitory manner on the signaling kinetics. This would be analogous to the observations of Wulfing et al. (73) that the loss of the ligand strength is reflected in the prolonged initiation of calcium elevation. The inhibitory effect of sCD4 on CD4+ T cells kinetics could argue that some kind of interference of transmembrane CD4 on CXCR4 activation may be a consequence of spatial restriction, since the receptor and coreceptors are found in close proximity in the cell membrane (39, 66, 75, 76). More specifically, CD4 as a signaling molecule could send a prerequisite signal that is insufficient for causing Ca2+ flux alone (39) but somehow modifies signaling through CXCR4 upon gp120-CXCR4 binding. This model is consistent with the qualitative differences in Ca2+ flux mediated by soluble CD4- and gp120-treated CD4+ T cells versus membrane-bound gp120-CD4 complexes, as previously mentioned. Therefore, a possible competition of two CD4 forms for gp120 could have either impaired the synergy of CD4-CXCR4 signaling or lowered the concentration of properly folded gp120 needed to engage the coreceptor in a functional gp120-CD4-CXCR4 complex.

Heterogeneity in response among individual cells was seen repeatedly. This argues for the existence of a subpopulation in an isolated primary CD4+ T-cell fraction that is sensitive to X4-tropic gp120, whereas a majority of cells never fluxed, even at high concentrations of stimuli. This differential response by primary unstimulated CD4+ T cells might be due to the disparate coreceptor expression levels on cells, the expression of different CXCR4 isoforms (42, 44, 64), or the presence of a quiescent T-cell population, or it might be a virus-induced response in only a certain type of peripheral blood CD4+ CXCR4+ T cells, such as naive, regulatory, or memory cells. In all of our experiments, up to ∼35% cells responded to the given stimuli, including chemokines, gp120m, or the virus, never reaching a 100% response. Since this observation has been previously reported (7, 60), it calls for further investigation.

We have found that the lowest effective concentration of monomeric X4-tropic gp120 was in the lower nanomolar range, and its in vivo relevance is still debatable (38). On the other hand, virion-bound gp120 was one thousand times more potent in inducing signaling in unstimulated primary CD4+ T cells. The lowest effective viral concentration was 10 ng of p24/ml, which corresponds to 0.42 nM p24 (23), ∼108 virions (43), ∼8 pM gp120, or 8.3 pg gp120 (23), which is significantly higher than the highest levels of HIV found in infected patients during acute infection (106 to 107 RNA copies/ml of plasma) (62). Therefore, even 10 ng of p24/ml appears to be superphysiological. However, we have found that two or three HIV particles or ca. 28 to 42 gp120 trimers (77) per cell was sufficient to activate Ca2+ signaling through CXCR4. In some cases, even one viral particle caused the signaling in T cells. Signal induced by a single virion is not improbable, since Irvine et al. (34) found that a single peptide ligand could activate TCR signaling in T cells and Baylor et al. (11) showed that retinal cells of the eye could detect single photons, indicating a maximum sensitivity for these signal transduction systems to minimal respective stimuli. The probability that two or three virions bind a CD4+ T-cell in vivo is very likely based on the range of plasma HIV RNA copies and CD4+ T-cell counts in chronically infected patients (21, 46, 68). Importantly, this signaling takes place in the absence of infection, since resting CD4+ T cells are refractory to infection. This indicates that virion-mediated signaling is likely to be happening at high frequency in infected individuals. In light of numerous reports that gp120-mediated signaling can have deleterious effects on cell function and even induce apoptosis (2, 6, 16), it is possible that such X4-tropic virion signaling may play a role in bystander effects in infected patients, contributing to the immunodeficiency without an active infection.

Based on our findings, we consider measurements of intracellular Ca2+ changes to be a sensitive and direct way to study the kinetics of coreceptor engagement during HIV entry. A real-time microscopy-based ex vivo system reveals responses in live natural target cells to wild-type virus at physiologically relevant concentrations and therefore involves the parameters necessary to establish a case of physiological significance. Using this system, we were able to detect CXCR4 signaling activation after the binding of two viral particles. The ability of a few virions to stimulate signaling in target cells without an active infection could have important implications in AIDS pathogenesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Robert W. Doms and the Neutralizing Antibody Consortium funded by the IAVI for the recombinant gp120HXB, Paul Bieniasz for the CHO-745/CycT cell lines, and Oliver Hartley for the AOP-RANTES. We also thank Julian Bess for purifying the viral preparations, Robert Stahelin for recommending Fluo-4, and Suchita Bhattacharyya and Edward Campbell for help with the fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis.

This study has been funded through the National Institutes of Health, grant RO1 AI52051 (to T.J.H.), and funded in part with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under contract N01-CO-12400. T.J.H. is an Elizabeth Glaser scientist.

The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does the mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 22 November 2006.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jvi.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alfano, M., H. Schmidtmayerova, C. A. Amella, T. Pushkarsky, and M. Bukrinsky. 1999. The B-oligomer of pertussis toxin deactivates CC chemokine receptor 5 and blocks entry of M-tropic HIV-1 strains. J. Exp. Med. 190:597-605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alimonti, J. B., T. B. Ball, and K. R. Fowke. 2003. Mechanisms of CD4+ T lymphocyte cell death in human immunodeficiency virus infection and AIDS. J. Gen. Virol. 84:1649-1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alkhatib, G., M. Locati, P. E. Kennedy, P. M. Murphy, and E. A. Berger. 1997. HIV-1 coreceptor activity of CCR5 and its inhibition by chemokines: independence from G protein signaling and importance of coreceptor downmodulation. Virology 234:340-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amara, A., A. Vidy, G. Boulla, K. Mollier, J. Garcia-Perez, J. Alcami, C. Blanpain, M. Parmentier, J. L. Virelizier, P. Charneau, and F. Arenzana-Seisdedos. 2003. G protein-dependent CCR5 signaling is not required for efficient infection of primary T lymphocytes and macrophages by R5 human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates. J. Virol. 77:2550-2558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aramori, I., S. S. Ferguson, P. D. Bieniasz, J. Zhang, B. Cullen, and M. G. Cullen. 1997. Molecular mechanism of desensitization of the chemokine receptor CCR-5: receptor signaling and internalization are dissociable from its role as an HIV-1 coreceptor. EMBO J. 16:4606-4616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arthos, J., C. Cicala, S. M. Selig, A. A. White, H. M. Ravindranath, D. Van Ryk, T. D. Steenbeke, E. Machado, P. Khazanie, M. S. Hanback, D. B. Hanback, R. L. Rabin, and A. S. Fauci. 2002. The role of the CD4 receptor versus HIV coreceptors in envelope-mediated apoptosis in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Virology 292:98-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arthos, J., A. Rubbert, R. L. Rabin, C. Cicala, E. Machado, K. Wildt, M. Hanbach, T. D. Steenbeke, R. Swofford, J. M. Farber, and A. S. Fauci. 2000. CCR5 signal transduction in macrophages by human immunodeficiency virus and simian immunodeficiency virus envelopes. J. Virol. 74:6418-6424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Atchison, R. E., J. Gosling, F. S. Monteclaro, C. Franci, L. Digilio, I. F. Charo, and M. A. Goldsmith. 1996. Multiple extracellular elements of CCR5 and HIV-1 entry: dissociation from response to chemokines. Science 274:1924-1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Babcock, G. J., T. Mirzabekov, W. Wojtowicz, and J. Sodroski. 2001. Ligand binding characteristics of CXCR4 incorporated into paramagnetic proteoliposomes. J. Biol. Chem. 276:38433-38440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Balabanian, K., J. Harriague, C. Decrion, B. Lagane, S. Shorte, F. Baleux, J. L. Virelizier, F. Arenzana-Seisdedos, and L. A. Chakrabarti. 2004. CXCR4-tropic HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein functions as a viral chemokine in unstimulated primary CD4+ T lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 173:7150-7160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baylor, D. A., T. D. Lamb, and K. W. Yau. 1979. Responses of retinal rods to single photons. J. Physiol. 288:613-634. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berkowitz, R. D., K. P. Beckerman, T. J. Schall, and J. M. McCune. 1998. CXCR4 and CCR5 expression delineates targets for HIV-1 disruption of T-cell differentiation. J. Immunol. 161:3702-3710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berridge, M. J. 1997. The AM and FM of calcium signalling. Nature 386:759-760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bess, J. W., Jr., R. J. Gorelick, W. J. Bosche, L. E. Henderson, and L. O. Arthur. 1997. Microvesicles are a source of contaminating cellular proteins found in purified HIV-1 preparations. Virology 230:134-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boutin, Y., D. Leitenberg, X. Tao, and K. Bottomly. 1997. Distinct biochemical signals characterize agonist- and altered peptide ligand-induced differentiation of naive CD4+ T cells into Th1 and Th2 subsets. J. Immunol. 159:5802-5809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cicala, C., J. Arthos, A. Rubbert, S. Selig, K. Wildt, O. J. Cohen, and A. S. Fauci. 2000. HIV-1 envelope induces activation of caspase-3 and cleavage of focal adhesion kinase in primary human CD4+ T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:1178-1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dimitrov, D. S., and R. Blumenthal. 1994. Photoinactivation and kinetics of membrane fusion mediated by the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein. J. Virol. 68:1956-1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dolmetsch, R. E., R. S. Lewis, C. C. Goodnow, and J. I. Healy. 1997. Differential activation of transcription factors induced by Ca2+ response amplitude and duration. Nature 386:855-858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dolmetsch, R. E., K. Xu, and R. S. Lewis. 1998. Calcium oscillations increase the efficiency and specificity of gene expression. Nature 392:933-936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doranz, B. J., S. S. Baik, and R. W. Doms. 1999. Use of a gp120 binding assay to dissect the requirements and kinetics of human immunodeficiency virus fusion events. J. Virol. 73:10346-10358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dybul, M., T. W. Chun, C. Yoder, B. Hidalgo, M. Belson, K. Hertogs, B. Larder, R. L. Dewar, C. H. Fox, C. W. Hallahan, J. S. Justement, S. A. Migueles, J. A. Metcalf, R. T. Davey, M. Daucher, P. Pandya, M. Baseler, D. J. Ward, and A. S. Fauci. 2001. Short-cycle structured intermittent treatment of chronic HIV infection with highly active antiretroviral therapy: effects on virologic, immunologic, and toxicity parameters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:15161-15166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eckert, D. M., and P. S. Kim. 2001. Mechanisms of viral membrane fusion and its inhibition. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 70:777-810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Esser, M. T., J. W. Bess, Jr., K. Suryanarayana, E. Chertova, D. Marti, M. Carrington, L. O. Arthur, and J. D. Lifson. 2001. Partial activation and induction of apoptosis in CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes by conformationally authentic noninfectious human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 75:1152-1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feng, Y., C. C. Broder, P. E. Kennedy, and E. A. Berger. 1996. HIV-1 entry cofactor: functional cDNA cloning of a seven-transmembrane, G protein-coupled receptor. Science 272:872-877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Francois, F., and M. E. Klotman. 2003. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase regulates human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication following viral entry in primary CD4+ T lymphocytes and macrophages. J. Virol. 77:2539-2549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gallo, S. A., A. Puri, and R. Blumenthal. 2001. HIV-1 gp41 six-helix bundle formation occurs rapidly after the engagement of gp120 by CXCR4 in the HIV-1 Env-mediated fusion process. Biochemistry 40:12231-12236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garcia, K. C. 1999. Molecular interactions between extracellular components of the T-cell receptor signaling complex. Immunol. Rev. 172:73-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garlick, R. L., R. J. Kirschner, F. M. Eckenrode, W. G. Tarpley, and C. S. Tomich. 1990. Escherichia coli expression, purification, and biological activity of a truncated soluble CD4. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 6:465-479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gilbert, M., J. Kirihara, and J. Mills. 1991. Enzyme-linked immunoassay for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein 120. J. Clin. Microbiol. 29:142-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Golding, H., M. Zaitseva, E. de Rosny, L. R. King, J. Manischewitz, I. Sidorov, M. K. Gorny, S. Zolla-Pazner, D. S. Dimitrov, and C. D. Weiss. 2002. Dissection of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 entry with neutralizing antibodies to gp41 fusion intermediates. J. Virol. 76:6780-6790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guntermann, C., B. J. Murphy, R. Zheng, A. Qureshi, P. A. Eagles, and K. E. Nye. 1999. Human immunodeficiency virus-1 infection requires pertussis toxin sensitive G-protein-coupled signaling and mediates cAMP downregulation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 256:429-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Horuk, R. 1999. Chemokine receptors and HIV-1: the fusion of two major research fields. Immunol. Today 20:89-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang, C. C., M. Tang, M. Y. Zhang, S. Majeed, E. Montabana, R. L. Stanfield, D. S. Dimitrov, B. Korber, J. Sodroski, I. A. Wilson, R. Wyatt, and P. D. Kwong. 2005. Structure of a V3-containing HIV-1 gp120 core. Science 310:1025-1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Irvine, D. J., M. A. Purbhoo, M. Krogsgaard, and M. M. Davis. 2002. Direct observation of ligand recognition by T cells. Nature 419:845-849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Iyengar, S., D. H. Schwartz, and J. E. Hildreth. 1999. T cell-tropic HIV gp120 mediates CD4 and CD8 cell chemotaxis through CXCR4 independent of CD4: implications for HIV pathogenesis. J. Immunol. 162:6263-6267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jones, P. L., T. Korte, and R. Blumenthal. 1998. Conformational changes in cell surface HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins are triggered by cooperation between cell surface CD4 and coreceptors. J. Biol. Chem. 273:404-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kinter, A., A. Catanzaro, J. Monaco, M. Ruiz, J. Justement, S. Moir, J. Arthos, A. Oliva, L. Ehler, S. Mizell, R. Jackson, M. Ostrowski, J. Hoxie, R. Offord, and A. S. Fauci. 1998. CC-chemokines enhance the replication of T-tropic strains of HIV-1 in CD4+ T cells: role of signal transduction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:11880-11885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Klasse, P. J., and J. P. Moore. 2004. Is there enough gp120 in the body fluids of HIV-1-infected individuals to have biologically significant effects? Virology 323:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kozak, S. L., J. M. Heard, and D. Kabat. 2002. Segregation of CD4 and CXCR4 into distinct lipid microdomains in T lymphocytes suggests a mechanism for membrane destabilization by human immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 76:1802-1815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.LaBranche, C. C., T. L. Hoffman, J. Romano, B. S. Haggarty, T. G. Edwards, T. J. Matthews, R. W. Doms, and J. A. Hoxie. 1999. Determinants of CD4 independence for a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variant map outside regions required for coreceptor specificity. J. Virol. 73:10310-10319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lapham, C. K., J. Ouyang, B. Chandrasekhar, N. Y. Nguyen, D. S. Dimitrov, and H. Golding. 1996. Evidence for cell-surface association between fusin and the CD4-gp120 complex in human cell lines. Science 274:602-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lapham, C. K., T. Romantseva, E. Petricoin, L. R. King, J. Manischewitz, M. B. Zaitseva, and H. Golding. 2002. CXCR4 heterogeneity in primary cells: possible role of ubiquitination. J. Leukoc. Biol. 72:1206-1214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Layne, S. P., M. J. Merges, M. Dembo, J. L. Spouge, S. R. Conley, J. P. Moore, J. L. Raina, H. Renz, H. R. Gelderblom, and P. L. Nara. 1992. Factors underlying spontaneous inactivation and susceptibility to neutralization of human immunodeficiency virus. Virology 189:695-714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lazarini, F., P. Casanova, T. N. Tham, E. De Clercq, F. Arenzana-Seisdedos, F. Baleux, and M. Dubois-Dalcq. 2000. Differential signaling of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 by stromal cell-derived factor 1 and the HIV glycoprotein in rat neurons and astrocytes. Eur. J. Neurosci. 12:117-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lewis, R. S. 2003. Calcium oscillations in T cells: mechanisms and consequences for gene expression. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 31:925-929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li, Q., T. Schacker, J. Carlis, G. Beilman, P. Nguyen, and A. T. Haase. 2004. Functional genomic analysis of the response of HIV-1-infected lymphatic tissue to antiretroviral therapy. J. Infect. Dis. 189:572-582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu, Q. H., D. A. Williams, C. McManus, F. Baribaud, R. W. Doms, D. Schols, E. De Clercq, M. I. Kotlikoff, R. G. Collman, and B. D. Freedman. 2000. HIV-1 gp120 and chemokines activate ion channels in primary macrophages through CCR5 and CXCR4 stimulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:4832-4837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Luster, A. D. 1998. Chemokines: chemotactic cytokines that mediate inflammation. N. Engl. J. Med. 338:436-445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Melikyan, G. B., R. M. Markosyan, H. Hemmati, M. K. Delmedico, D. M. Lambert, and F. S. Cohen. 2000. Evidence that the transition of HIV-1 gp41 into a six-helix bundle, not the bundle configuration, induces membrane fusion. J. Cell Biol. 151:413-423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mkrtchyan, S. R., R. M. Markosyan, M. T. Eadon, J. P. Moore, G. B. Melikyan, and F. S. Cohen. 2005. Ternary complex formation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Env, CD4, and chemokine receptor captured as an intermediate of membrane fusion. J. Virol. 79:11161-11169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mo, H., S. Monard, H. Pollack, J. Ip, G. Rochford, L. Wu, J. Hoxie, W. Borkowsky, D. D. Ho, and J. P. Moore. 1998. Expression patterns of the HIV type 1 coreceptors CCR5 and CXCR4 on CD4+ T cells and monocytes from cord and adult blood. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 14:607-617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.O'Malley, D. M., B. J. Burbach, and P. R. Adams. 1999. Fluorescent calcium indicators: subcellular behavior and use in confocal imaging. Methods Mol. Biol. 122:261-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Parolin, C., A. Borsetti, H. Choe, M. Farzan, P. Kolchinsky, M. Heesen, Q. Ma, C. Gerard, G. Palu, M. E. Dorf, T. Springer, and J. Sodroski. 1998. Use of murine CXCR-4 as a second receptor by some T-cell-tropic human immunodeficiency viruses. J. Virol. 72:1652-1656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Platt, E. J., J. P. Durnin, and D. Kabat. 2005. Kinetic factors control efficiencies of cell entry, efficacies of entry inhibitors, and mechanisms of adaptation of human immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 79:4347-4356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pontow, S. E., N. V. Heyden, S. Wei, and L. Ratner. 2004. Actin cytoskeletal reorganizations and coreceptor-mediated activation of rac during human immunodeficiency virus-induced cell fusion. J. Virol. 78:7138-7147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Popik, W., J. E. Hesselgesser, and P. M. Pitha. 1998. Binding of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 to CD4 and CXCR4 receptors differentially regulates expression of inflammatory genes and activates the MEK/ERK signaling pathway. J. Virol. 72:6406-6413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Popik, W., and P. M. Pitha. 2000. Exploitation of cellular signaling by HIV-1: unwelcome guests with master keys that signal their entry. Virology 276:1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Popik, W., and P. M. Pitha. 2000. Inhibition of CD3/CD28-mediated activation of the MEK/ERK signaling pathway represses replication of X4 but not R5 human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in peripheral blood CD4+ T lymphocytes. J. Virol. 74:2558-2566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Raviv, Y., M. Viard, J. Bess, Jr., and R. Blumenthal. 2002. Quantitative measurement of fusion of HIV-1 and SIV with cultured cells using photosensitized labeling. Virology 293:243-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Roederer, M., M. Bigos, T. Nozaki, R. T. Stovel, D. R. Parks, and L. A. Herzenberg. 1995. Heterogeneous calcium flux in peripheral T-cell subsets revealed by five-color flow cytometry using log-ratio circuitry. Cytometry 21:187-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sattentau, Q. J., J. P. Moore, F. Vignaux, F. Traincard, and P. Poignard. 1993. Conformational changes induced in the envelope glycoproteins of the human and simian immunodeficiency viruses by soluble receptor binding. J. Virol. 67:7383-7393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schacker, T., S. Little, E. Connick, K. Gebhard, Z. Q. Zhang, J. Krieger, J. Pryor, D. Havlir, J. K. Wong, R. T. Schooley, D. Richman, L. Corey, and A. T. Haase. 2001. Productive infection of T cells in lymphoid tissues during primary and early human immunodeficiency virus infection. J. Infect. Dis. 183:555-562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schols, D., S. Struyf, J. Van Damme, J. A. Este, G. Henson, and E. De Clercq. 1997. Inhibition of T-tropic HIV strains by selective antagonization of the chemokine receptor CXCR4. J. Exp. Med. 186:1383-1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sloane, A. J., V. Raso, D. S. Dimitrov, X. Xiao, S. Deo, N. Muljadi, D. Restuccia, S. Turville, C. Kearney, C. C. Broder, H. Zoellner, A. L. Cunningham, L. Bendall, and G. W. Lynch. 2005. Marked structural and functional heterogeneity in CXCR4: separation of HIV-1 and SDF-1α responses. Immunol. Cell Biol. 83:129-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stantchev, T. S., and C. C. Broder. 2001. Human immunodeficiency virus type-1 and chemokines: beyond competition for common cellular receptors. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 12:219-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Steffens, C. M., and T. J. Hope. 2003. Localization of CD4 and CCR5 in living cells. J. Virol. 77:4985-4991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Timmerman, L. A., N. A. Clipstone, S. N. Ho, J. P. Northrop, and G. R. Crabtree. 1996. Rapid shuttling of NF-AT in discrimination of Ca2+ signals and immunosuppression. Nature 383:837-840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Trkola, A., H. Kuster, C. Leemann, C. Ruprecht, B. Joos, A. Telenti, B. Hirschel, R. Weber, S. Bonhoeffer, and H. F. Gunthard. 2003. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 fitness is a determining factor in viral rebound and set point in chronic infection. J. Virol. 77:13146-13155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Trubey, C. M., E. Chertova, L. V. Coren, J. M. Hilburn, C. V. Hixson, K. Nagashima, J. D. Lifson, and D. E. Ott. 2003. Quantitation of HLA class II protein incorporated into human immunodeficiency type 1 virions purified by anti-CD45 immunoaffinity depletion of microvesicles. J. Virol. 77:12699-12709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vaca, L., and A. Sampieri. 2002. Calmodulin modulates the delay period between release of calcium from internal stores and activation of calcium influx via endogenous TRP1 channels. J. Biol. Chem. 277:42178-42187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Weissman, D., R. L. Rabin, J. Arthos, A. Rubbert, M. Dybul, R. Swofford, S. Venkatesan, J. M. Farber, and A. S. Fauci. 1997. Macrophage-tropic HIV and SIV envelope proteins induce a signal through the CCR5 chemokine receptor. Nature 389:981-985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wu, L., N. P. Gerard, R. Wyatt, H. Choe, C. Parolin, N. Ruffing, A. Borsetti, A. A. Cardoso, E. Desjardin, W. Newman, C. Gerard, and J. Sodroski. 1996. CD4-induced interaction of primary HIV-1 gp120 glycoproteins with the chemokine receptor CCR-5. Nature 384:179-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wulfing, C., J. D. Rabinowitz, C. Beeson, M. D. Sjaastad, H. M. McConnell, and M. M. Davis. 1997. Kinetics and extent of T-cell activation as measured with the calcium signal. J. Exp. Med. 185:1815-1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wyatt, R., and J. Sodroski. 1998. The HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins: fusogens, antigens, and immunogens. Science 280:1884-1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Xiao, X., A. Kinter, C. C. Broder, and D. S. Dimitrov. 2000. Interactions of CCR5 and CXCR4 with CD4 and gp120 in human blood monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 68:133-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Xiao, X., L. Wu, T. S. Stantchev, Y. R. Feng, S. Ugolini, H. Chen, Z. Shen, J. L. Riley, C. C. Broder, Q. J. Sattentau, and D. S. Dimitrov. 1999. Constitutive cell surface association between CD4 and CCR5. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:7496-7501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhu, P., J. Liu, J. Bess, Jr., E. Chertova, J. D. Lifson, H. Grise, G. A. Ofek, K. A. Taylor, and K. H. Roux. 2006. Distribution and three-dimensional structure of AIDS virus envelope spikes. Nature 441:847-852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.