Abstract

RNA motifs comprising nucleotides that interact through non-Watson-Crick base pairing play critical roles in RNA functions, often by serving as the sites for RNA-RNA, RNA-protein, or RNA small ligand interactions. The structures of viral and viroid RNA motifs are studied commonly by in vitro, computational, and mutagenesis approaches. Demonstration of the in vivo existence of a motif will help establish its biological significance and promote mechanistic studies on its functions. By using UV cross-linking and primer extension, we have obtained direct evidence for the in vivo existence of the loop E motif of Potato spindle tuber viroid. We present our findings and discuss their biological implications.

RNA motifs comprising nucleotides that interact through non-Watson-Crick base pairing play critical roles in RNA functions, often by serving as the sites for interactions with proteins, other RNA motifs, or small ligands (19). For viral and viroid RNAs, such interactions are crucial for the establishment of infection. The structures of RNA motifs of viral and viroid RNAs have been generally studied by in vitro chemical/enzymatic mapping, thermodynamic calculations using minimum free energy, biophysical characterization, and mutational analyses. It has been shown experimentally that some structural features of RNAs deduced by in vitro and in silico methods may not be identical to those found in vivo, likely because of the influence of cellular factors that interact with the RNAs (2, 26, 30). Therefore, to further establish the biological significance of findings from in vitro and in silico approaches, the in vivo existence of an RNA motif should be directly demonstrated.

We are interested in using viroid infection as a model system to investigate the structure-function relationships of RNA motifs. Viroids are the smallest known nucleic acid-based infectious agents and self-replicating genetic units. Their genomes consist of single-stranded, circular RNAs ranging in size from 250 to 400 nucleotides (12, 13, 33). Viroids do not encode proteins, do not have encapsidation mechanisms, and do not require helper viruses. Nonetheless, they can replicate efficiently and spread throughout an infected plant (13, 33). Thus, viroid infection provides an excellent experimental system to investigate the basic RNA structure-function relationships for infection as well as for RNA biology (18).

One of the best-studied viroid RNA motifs is the so-called loop E located in the central conserved region of Potato spindle tuber viroid (PSTVd). The loop E is a recurrent motif found in many RNAs, including 5S, 16S, and 23S rRNAs, group I and group II introns, bacterial RNase P, ribozyme of Tobacco ringspot virus satellite RNA (20), and lysine riboswitches (15, 31), where it plays critical roles in RNA-RNA and RNA-protein interactions. UV-induced cross-linking between G98 and U260 in vitro provided the first evidence for the existence of local tertiary structure in the loop E of PSTVd resembling that of the loop E of 5S rRNA from HeLa cells (6) (Fig. 1). A recent model depicts all of the non-Watson-Crick base pairs within the PSTVd loop E (37) (Fig. 1). This motif is involved in replication (24, 37), in vitro processing (3), pathogenicity (25), and host adaptation (24, 35, 38).

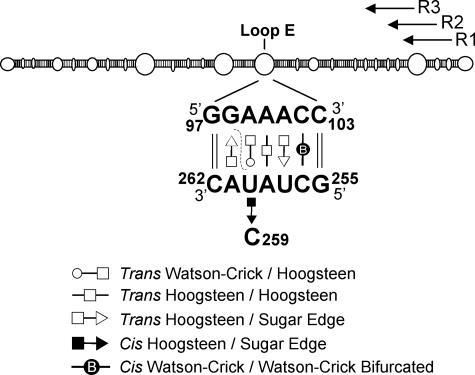

FIG. 1.

Secondary structure of PSTVd (upper panel) (14) and non-Watson-Crick base pairs in loop E (lower panel) (37). The symbols that denote each of the specific base edge-edge interactions are defined below the structure (for details, see references 21 and 37). The dashed line indicates G98 and U260, which can be cross-linked by UV irradiation. R1, R2, and R3 indicate the positions of the primers used in the primer extension experiments.

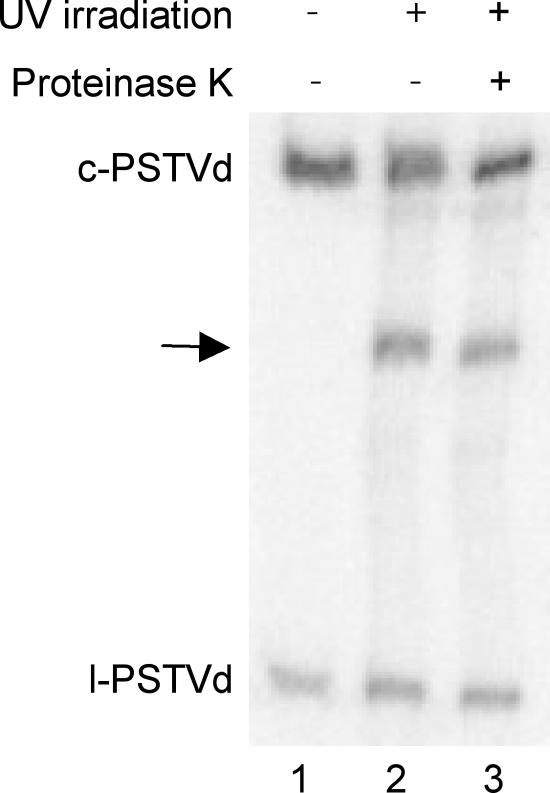

In this study we investigated the existence of PSTVd loop E in infected tomato leaves by UV cross-linking, following the protocols of Daròs and Flores (10). Pilot experiments established that 80 min of 254-nm UV irradiation (10 J/cm2; Stratalinker model 1800; Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) was optimal to detect cross-linked products derived from PSTVd. After UV irradiation, we extracted total RNAs from the leaves for RNA gel blot analyses using riboprobes specific for the (+)-strand PSTVd. Compared to nonirradiated samples (Fig. 2, lane 1), a band with a gel mobility that is intermediate between those of the circular and linear PSTVd RNAs was detected (Fig. 2, lane 2). Proteinase K treatment showed that the presence of this intermediate band was not due to protein binding to the viroid RNA (Fig. 2, lane 3).

FIG. 2.

RNA gel blot showing the appearance of a UV-cross-linked product (arrow) of PSTVd RNAs from infected tomato leaves. Treatment with proteinase K (0.5 units for 30 min; Invitrogen) indicates that this cross-linked product is not attributed to protein binding. c-PSTVd and l-PSTVd denote circular and linear PSTVd RNAs, respectively. For gel blotting, total RNAs were extracted from infected tomato leaves that were untreated or irradiated with UV for 80 min (10 J/cm2) by using the RNeasy plant mini kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA). RNA samples were run on 5% polyacrylamide-8 M urea gels, transferred to Hybond-XL nylon membranes (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) using a vacuum blotting system (Amersham), and immobilized by UV cross-linking. After overnight hybridization with [α-32P]UTP-labeled riboprobes at 65°C in ULTRAhyb reagent (Ambion, Austin, TX), the membranes were washed twice at 65°C in 2× SSC-0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) and 0.2× SSC-0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate and exposed to a Storage phosphor screen (Kodak, Rochester, NY).

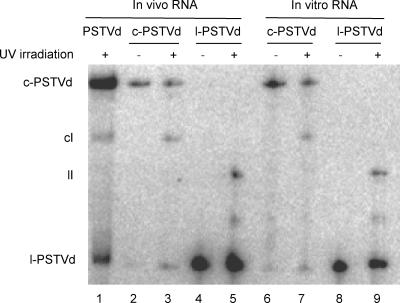

To determine whether the UV-cross-linked product was derived from the circular or linear PSTVd RNA or both, we gel purified the circular and linear RNAs from infected tomato leaves for UV cross-linking. As shown in lane 3 of Fig. 3, UV treatment of the circular RNAs yielded a product with a mobility similar or identical to that detected from UV-treated tomato leaves. UV treatment of the linear RNAs yielded a product of faster mobility (Fig. 3, lane 5). The different mobilities of the cross-linked products derived from the circular and linear PSTVd RNAs are likely attributable to their different conformations. These results suggest that the UV-cross-linked product from PSTVd-infected plants was mostly derived from the circular genomic RNA of PSTVd. The cross-linked product derived from the linear RNAs in tomato leaves was present at a very low level, likely because of the relatively low amounts of linear RNAs, which were barely visible only with overexposure (data not shown). The band observed between the cross-linked product and the linear substrate RNA was also observed in previous experiments, and its nature remains to be determined (28, 37).

FIG. 3.

RNA gel blot showing the origin of the in vivo UV-cross-linked product predominantly from the circular PSTVd RNAs. Total RNAs were extracted and run on 5% polyacrylamide-8 M urea gels as described in the legend for Fig. 2. The in vivo circular PSTVd (c-PSTVd) and linear PSTVd (l-PSTVd) RNAs were gel purified and irradiated with UV for 5 min in EXL buffer (600 mM NaCl, 4 M urea, 1 mM cacodylate, 0.1 mM EDTA) as described by Zhong et al. (37). In vitro transcripts of PSTVd were obtained by transcribing HindIII-linearized pRZ6-2 template (17) by utilizing a T7 MAXIscript kit (Ambion). Unit-length l-PSTVd RNAs were gel purified from the 5% polyacrylamide-8 M urea gel. Incubation of the l-PSTVd transcripts in wheat germ extract gave rise to the circular PSTVd RNAs, which were run on a 5% polyacrylamide-8 M urea gel followed by gel purification. Both c-PSTVd and l-PSTVd in vitro transcripts were subjected to UV irradiation for 5 min in the EXL buffer. Approximately 100 to 200 ng of RNA was loaded for each lane.

It has been well established, via enzymatic mapping (6), primer extension (3), and mutational (37) analyses, that in vitro UV cross-linking of PSTVd occurs within loop E. Thus, a key question is whether the observed UV-induced cross-linking in vivo also occurs within loop E. To address this question, we first compared the gel mobilities of cross-linked products from circular and linear in vitro transcripts of PSTVd with those from the in vivo PSTVd RNAs, under the assumption that cross-linking at the same sites should give rise to products of the same gel mobilities for either the circular or linear substrate RNAs. We used linearized plasmid pRZ6-2 (17) as a template to synthesize the linear PSTVd transcripts. Ribozyme-mediated self-cleavage of the transcripts gave rise to unit-length PSTVd RNAs. Incubation of the linear PSTVd transcripts in wheat germ extract yielded circular PSTVd RNAs (11, 37). Both the unit-length linear and circular RNAs were gel purified for UV treatment. As shown in lanes 7 and 9 of Fig. 3, the UV-cross-linked products derived from the in vitro circularized and linear RNAs had gel mobilities comparable to those derived from the in vivo PSTVd RNAs. As a negative control, UV irradiation of green fluorescent protein RNAs did not produce any cross-linked products (data not shown) (37). These results suggest that UV-induced cross-linking of PSTVd RNAs in vivo occurs within loop E, as is the case for UV-induced cross-linking in vitro.

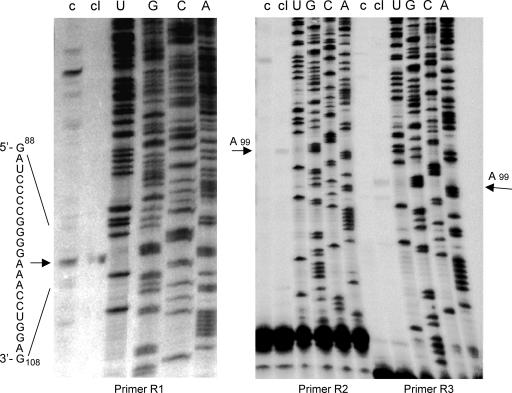

To demonstrate directly UV-induced cross-linking within loop E in vivo, we conducted primer extension experiments. We gel purified the UV-cross-linked as well as the circular PSTVd RNAs from infected tomato leaves as templates for reverse transcription to map one of the candidate cross-linking sites, G98. The reverse transcription was carried out following the protocols described by Baumstark et al. (3) with modifications, using primer R1 (5′-AAACCCTGTTTCGGCGGGAATTAC-3′, complementary to position 154-179 on the PSTVd genome) (Fig. 1) and the SuperScript III RNase H- reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) at 52°C for 40 min. As shown in Fig. 4, reverse transcription terminated predominantly at A99 when the cross-linked PSTVd RNA was used as the template (lane cI), compared to the situation when the non-cross-linked circular PSTVd RNA was used as the template (lane c). Identical results were obtained when two other primers (R2, 5′-TTTCGGCGGGAATTACTCCTGTCGGC-3′, complementary to position 146-171 on the PSTVd genome, and R3, 5′-ATTACTCCTGTCGGCCGCTGGG-3′, complementary to position 139-160 on the PSTVd genome) were used for reverse transcription (Fig. 4). All together, these results indicated that G98 was a cross-linking site, identical to that mapped in vitro (3, 6), providing direct evidence for UV-induced cross-linking within loop E in vivo.

FIG. 4.

Primer extension mapping of an in vivo cross-linking site to G98 of loop E, using three different primers as indicated (R1, R2, and R3). Lane c, cDNAs from reverse transcription of the circular PSTVd RNA template purified from infected tomato leaves; lane cI, cDNAs from reverse transcription of the UV cross-linked circular PSTVd RNA template purified from infected leaves. The reverse transcription was performed by following the protocols of Baumstark et al. (3) with modifications, using Invitrogen Superscript III RNase H- reverse transcriptase and 32P-labeled primers for 40 min at 52°C. Lanes U to A, sequencing ladders generated by PCR with pRZ6-2 template and 32P-labeled primers in the presence of ddATP, ddCTP, ddGTP, and ddUTP by utilizing the Thermo Sequenase cycle sequencing kit (USB, Cleveland, OH). All samples were run on an 8% polyacrylamide-8 M urea sequencing gel. The nucleotide sequence of the (+)-PSTVd is given on the left, and the arrows point to the bands corresponding to reverse transcription termination at A99.

Comparative sequence analysis using isostericity matrices in combination with mutational and functional studies suggested that the PSTVd loop E exists and functions in vivo (37). The results from the UV-cross-linking experiments presented here provide conclusive evidence for the in vivo existence of PSTVd loop E, establishing a firm structural foundation for further mechanistic studies on the role of this motif in the viroid life cycle. Another important ramification is that these findings support the notion that the rod-shaped native structure of PSTVd also exists in vivo. This is consistent with the observation that deletion mutations that restored the rod-shaped PSTVd structure restored infectivity (34) and supports the biological significance of the pathogenicity model based on the bending of the rod-shaped structure of PSTVd (23, 27). The model that the genomic PSTVd RNA exists as a rod-shaped structure in vivo implies that many, if not all, of the predicted loop and bulge motifs present in this genomic structure (Fig. 1) likely have distinct biological functions yet to be elucidated. It should be noted that a metastable hairpin II structure that may play a role in replication has also been detected in vivo as well as in vitro (29). Altogether, these studies bring us one significant step towards elucidating the in vivo structures and functions of viroid RNA motifs.

UV cross-linking has been used for detecting tertiary interactions in vitro in a wide range of RNAs, for example, hepatitis delta virus (5, 7, 9), tRNAs (4), small nuclear RNAs (32), hairpin ribozymes (8), ribosomal RNAs (22), and Peach latent mosaic viroid (16). As shown here, this approach may be extended to investigate the in vivo existence of these tertiary interactions. As has also been well demonstrated by studies on cellular and viral RNAs (1, 2, 26, 36), probing the in vivo structure of RNA motifs will be necessary to further establish the biological significance of cellular and viral RNA motifs deduced from in vitro and in silico studies.

Acknowledgments

We thank Zidian Xie for technical assistance with primer extension. We thank Iris Meier, Xiaorong Tao, and Ryuta Takeda for discussions.

This work was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation (IBN-0238412, IOB-0515745, and IOB-0620143).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 29 November 2006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Atmadja, J., R. Brimacombe, H. Blöcker, and R. Frank. 1985. Investigation of the tertiary folding of Escherichia coli 16s RNA by in situ intra-RNA crosslinking within 30S ribosomal subunits. Nucleic Acids Res. 13:6919-6936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baumstark, T., and P. Ahlquist. 2001. The brome mosaic virus RNA3 intergenic replication enhancer folds to mimic a tRNA TpsiC-stem loop and is modified in vivo. RNA 7:1652-1670. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baumstark, T., A. R. W. Schröder, and D. Riesner. 1997. Viroid processing: switch from cleavage to ligation is driven by a change from a tetraloop to a loop E conformation. EMBO J. 16:599-610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Behlen, L. S., J. R. Sampson, and O. C. Uhlenbeck. 1992. An ultraviolet light-induced crosslink in yeast tRNAPhe. Nucleic Acids Res. 20:4055-4059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Branch, A. D., B. J. Benenfeld, B. M. Baroudy, F. V. Wells, J. L. Gerin, and H. D. Robertson. 1989. An ultraviolet-sensitive RNA structural element in a viroid-like domain of the hepatitis delta virus. Science 243:649-652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Branch, A. D., B. J. Benenfeld, and H. D. Robertson. 1985. Ultraviolet light-induced crosslinking reveals a unique region of local tertiary structure in potato spindle tuber viroid and HeLa 5S RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 82:6590-6594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Branch, A. D., B. J. Levine, and J. A. Polaskova. 1995. An RNA tertiary structure of the hepatitis delta agent contains UV-sensitive bases U-712 and U-865 and can form in a bimolecular complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 23:491-499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Butcher, S. E., and J. M. Burke. 1994. A photo-cross-linkable tertiary structure motif found in functionally distinct RNA molecules essential for catalytic function of the hairpin ribozyme. Biochemistry 33:992-999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Circle, D. A., A. J. Lyons, O. D. Neel, and H. D. Robertson. 2003. Recurring features of local tertiary structural elements in RNA molecules exemplified by hepatitis D virus RNA. RNA 9:280-286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daròs, J. A., and R. Flores. 2002. A chloroplast protein binds a viroid RNA in vivo and facilitates its hammerhead-mediated self-cleavage. EMBO J. 21:749-759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feldstein, P. A., Y. Hu, and R. A. Owens. 1998. Precisely full length, circularizable, complementary RNA: an infectious form of potato spindle tuber viroid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:6560-6565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flores, R., J. A. Daròs, and C. Hernández. 2000. Avsunviroidae family: viroids containing hammerhead ribozymes. Adv. Virus Res. 55:271-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flores, R., C. Hernández, A. E. Martínez, J. A. Daròs, and F. Di Serio. 2005. Viroids and viroid-host interactions. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 43:117-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gross, H. J., H. Domdey, C. Lossow, P. Jank, M. Raba, H. Alberty, and H. L. Sänger. 1978. Nucleotide sequence and secondary structure of potato spindle tuber viroid. Nature 273:203-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grundy, F. J., S. C. Lehman, and T. M. Henkin. 2003. The L box regulon: lysine sensing by leader RNAs of bacterial lysine biosynthesis genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:12057-12062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hernández, C., F. Di Serio, S. Ambrós, J.-A. Daròs, and R. Flores. 2006. An element of the tertiary structure of Peach latent mosaic viroid RNA revealed by UV irradiation. J. Virol. 80:9336-9340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu, Y., P. A. Feldstein, J. Hammond, R. W. Hammond, P. J. Bottino, and R. A. Owens. 1997. Destabilization of potato spindle tuber viroid by mutations in the left terminal loop. J. Gen. Virol. 78:1199-1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Itaya, A., and B. Ding. 2007. Viroid: a useful model for studying the basic principles of infection and RNA biology. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 20:7-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leontis, N. B., J. Stombaugh, and E. Westhof. 2002. Motif prediction in ribosomal RNAs: lessons and prospects for automated motif prediction in homologous RNA molecules. Biochimie 84:961-973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leontis, N. B., and E. Westhof. 1998. A common motif organizes the structure of multi-helix loops in 16 S and 23 S ribosomal RNAs. J. Mol. Biol. 283:571-583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leontis, N. B., and E. Westhof. 2001. Geometric nomenclature and classification of RNA base pairs. RNA 7:499-512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Noah, J. W., T. Shapkina, and P. Wollenzien. 2000. UV-induced crosslinks in the 16S rRNAs of Escherichia coli, Bacillus subtilis and Thermus aquaticus and their implications for ribosome structure and photochemistry. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:3785-3792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Owens, R. A., G. Steger, Y. Hu, A. Fels, R. W. Hammond, and D. Riesner. 1996. RNA structural features responsible for potato spindle tuber viroid pathogenicity. Virology 222:144-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qi, Y., and B. Ding. 2002. Replication of Potato spindle tuber viroid in cultured cells of tobacco and Nicotiana benthamiana: the role of specific nucleotides in determining replication levels for host adaptation. Virology 302:445-456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qi, Y., and B. Ding. 2003. Inhibition of cell growth and shoot development by a specific nucleotide sequence in a noncoding viroid RNA. Plant Cell 15:1360-1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodriguez-Alvarado, G., and M. J. Roossinck. 1997. Structural analysis of a necrogenic strain of cucumber mosaic cucumovirus satellite RNA in planta. Virology 236:155-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmitz, A., and D. Riesner. 1998. Correlation between bending of the VM region and pathogenicity of different Potato spindle tuber viroid strains. RNA 4:1295-1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schrader, O., T. Baumstark, and D. Riesner. 2003. A Mini-RNA containing the tetraloop, wobble-pair and loop E motifs of the central conserved region of potato spindle tuber viroid is processed into a minicircle. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:988-998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schröder, A. R. W., and D. Riesner. 2002. Detection and analysis of hairpin II, an essential metastable structural element in viroid replication intermediates. Nucleic Acids Res. 30:3349-3359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Senecoff, J. F., and R. B. Meagher. 1992. In vivo analysis of plant RNA structure: soybean 18S ribosomal and ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase small subunit RNAs. Plant Mol. Biol. 18:219-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sudarsan, N., J. K. Wickiser, S. Nakamura, M. S. Ebert, and R. R. Breaker. 2003. An mRNA structure in bacteria that controls gene expression by binding lysine. Genes Dev. 17:2688-2697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sun, J. S., S. Valadkhan, and J. L. Manley. 1998. A UV-crosslinkable interaction in human U6 snRNA. RNA 4:489-497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tabler, M., and M. Tsagris. 2004. Viroids: petite RNA pathogens with distinguished talents. Trends Plant Sci. 9:339-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wassenegger, M., S. Heimes, and H. L. Sänger. 1994. An infectious viroid RNA replicon evolved from an in vitro-generated non-infectious viroid deletion mutant via a complementary deletion in vivo. EMBO J. 13:6172-6177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wassenegger, M., R. L. Spieker, S. Thalmeir, F. U. Gast, L. Riedel, and H. L. Sänger. 1996. A single nucleotide substitution converts potato spindle tuber viroid (PSTVd) from a noninfectious to an infectious RNA for Nicotiana tabacum. Virology 226:191-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Watkins, K. P., and N. Agabian. 1991. In vivo UV cross-linking of U snRNAs that participate in trypanosome trans-splicing. Genes Dev. 5:1859-1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhong, X., N. Leontis, S. Qian, A. Itaya, Y. Qi, K. Boris-Lawrie, and B. Ding. 2006. Tertiary structural and functional analyses of a viroid RNA motif by isostericity matrix and mutagenesis reveal its essential role in replication. J. Virol. 80:8566-8581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhu, Y., Y. Qi, Y. Xun, R. Owens, and B. Ding. 2002. Movement of potato spindle tuber viroid reveals regulatory points of phloem-mediated RNA traffic. Plant Physiol. 130:138-146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]