Abstract

We report here the significance of the Notch1 receptor in intracellular trafficking of recombinant adeno-associated virus type 2 (rAAV2). RNA profiling of human prostate cancer cell lines with various degrees of AAV transduction indicated a correlation of the amount of Notch1 with rAAV transgene expression. A definitive role of Notch1 in enhancing AAV transduction was confirmed by developing clonal derivatives of DU145 cells overexpressing either full-length or intracellular Notch1. To discern stages of AAV2 transduction influenced by Notch1, competitive binding with soluble heparin and Notch1 antibody, intracellular trafficking using Cy3-labeled rAAV2, and blocking assays for proteasome and dynamin pathways were performed. Results indicated that in the absence or low-level expression of Notch1, only binding of virus was found on the cell surface and internalization was impaired. However, increased Notch1 expression in these cells allowed efficient perinuclear accumulation of labeled capsids. Nuclear transport of the vector was evident by transgene expression and real-time PCR analyses. Dynamin levels were not found to be different among these cell lines, but blocking dynamin function abrogated AAV2 transduction in DU145 clones overexpressing full-length Notch1 but not in clones overexpressing intracellular Notch1. These studies provide evidence for the role of activated Notch1 in intracellular trafficking of AAV2, which may have implications in the optimal use of AAV2 in human gene therapy.

Recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV) has attracted considerable interest as an efficient and safe gene therapy vector. The most commonly studied AAV vector for gene transfer is derived from serotype 2 (5, 8, 15). Initial binding and internalization of AAV type 2 (AAV2) have been attributed to the heparan sulfate proteoglycan receptor (20) and the αvβ5 integrin and fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 coreceptors (13, 21). Once internalized, nuclear trafficking and transgene expression following complementary strand formation are known to be aided by many cellular factors, such as dynamin, Rac1, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, and T-cell protein tyrosine phosphatase (9, 16, 17, 22).

The present study demonstrates that Notch1 plays an important role in mediating intracellular trafficking and nuclear transport of AAV2. Notch1 is a transmembrane receptor, expressed as a heterodimeric protein after intracellular processing of the full-length protein (1). Notch protein requires three cleavage steps to become fully functional (4). Engagement by ligand results in the cleavage of the Notch heterodimer, releasing the intracellular domain of Notch and allowing translocation to the nucleus. Notch-mediated cell-cell interaction and signaling are important for stem cell maintenance, cell fate determination, cell proliferation, and differentiation in a variety of tissues. The significance of the Notch pathway in proliferation and gene expression of Epstein-Barr virus, Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus, adenovirus, human papillomavirus, and simian virus 40 has previously been reported (6, 7, 10-12, 14). In addition to its role in promoting gene expression, activated Notch has been shown to affect nuclear trafficking of ubiquitin ligase protein and activate phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, Rho, and Rac proteins (2, 19). Previous studies have demonstrated that endosomal escape and nuclear localization of AAV2 are mediated by these proteins and a role for dynamin in the release of endosomally encapsulated vector (3, 9). Further, the activation of full-length Notch1 is also known to involve dynamin interaction (18).

Gene expression profile correlating with rAAV2 transduction.

In our studies on AAV2 transduction to human epithelial prostate cancer cells, we observed a wide variation in transduction efficiency. Whereas PCa2b cells indicated the highest AAV2 gene transfer, a moderate amount of rAAV2 transgene expression was seen in LNCaP cells and much lower expression was seen in DU145 cells (Fig. 1A). As a first step towards identifying specifically active genes in these cells, RNA microarray analysis was performed using Affymetrix GeneChip with 293, PCa2b, DU145, and M07e cells. Clustering of the data, correlating with reporter gene expression, resulted in the identification of six differently expressed genes. Out of the six different genes, one encoded a structural protein (desmoplakin) and five proteins with functional significance (SRY box 9, N-Myc downstream-regulated gene 1, chloride channel protein 3, phosphatidic acid phosphatase type 2A, and Notch1) at the membrane, cytoplasmic, or nuclear compartment.

FIG. 1.

Variation in rAAV2 transduction efficiency in human epithelial prostate cancer cells and inhibition of rAAV2 transduction by Notch1 siRNA. (A) 293, PCa2b, DU145, and M07e cells were transduced with 1 MOI of rAAV2 GFP. Transgene expression was monitored in a fluorescence microscope 48 h later. (B) Monolayer cultures of 293 and PCa2b cells were transfected with synthetic siRNA oligonucleotide for human Notch1, after which the cells were infected with 100 MOI of rAAV2 luciferase. Forty-eight hours later, the cells were lysed and luciferase activity measured. The data shown indicate the expression of luciferase activity in Notch1 siRNA-transfected cells (black bars) compared to that in cells with no siRNA (white bars). The assay was done in triplicate.

Notch1 expression correlates with rAAV2 transduction.

To determine whether any of the above proteins influences rAAV2 transduction, we carried out either blocking studies with antibodies (for chloride channel protein 3, phosphatidic acid phosphatase type 2A, and desmoplakin proteins) or small interfering RNA (siRNA) (for Notch1) in cells which showed upregulation or overexpression studies using expression vectors (for SRY box 9 and N-Myc downstream-regulated gene 1) in cells which showed low-level expression. Data from these studies indicated significant influence on AAV2 transduction only following siRNA inhibition of Notch1, as shown in Fig. 1B. rAAV2 transduction in Notch siRNA-transfected PCa2b and 293 cells was inhibited by 75.6% (P < 0.0007) and 97.5% (P < 0.0001), respectively. Altering the expression of the other five proteins did not significantly change the efficiency of rAAV2 transduction (data not shown). These data strongly suggest a correlation of the amount of Notch1 transcript with rAAV2 transduction.

Establishment of stable cell lines expressing the full-length or the intracellular domain of Notch1 and characterization of rAAV2 transduction.

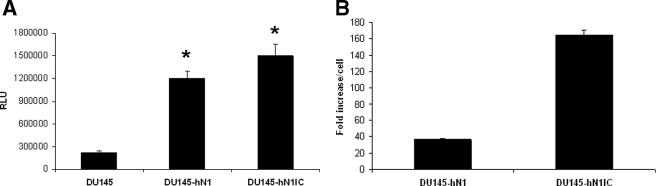

In the next set of experiments, we sought to determine whether overexpression of Notch1 in DU145 cells would render them more permissive for rAAV2 transduction. To determine whether full-length or intracellular Notch1 is responsible for enhancing rAAV2 transduction, we developed independent clones of DU145 expressing either full-length (DU145-hN1) or intracellular (DU145-hN1IC) Notch1 by G418 selection and tested for augmentation of rAAV2 transduction by infecting the clones with 100 multiplicities of infection (MOI) of rAAV2 encoding luciferase. The results showed a significant increase in luciferase expression in DU145 clones overexpressing either the full-length or the intracellular domain of Notch1 (P < 0.02) (Fig. 2A). Quantitative real-time PCR for the vector genome indicated significantly higher copy numbers of rAAV2 DNA in DU145-hN1 and DU145-hN1IC cells than in parental DU145 cells following transduction with the same vector MOI (Fig. 2B). Competitive binding with Notch1 antibody did not block vector transduction, indicating that Notch1 does not serve as a receptor or coreceptor for virus binding.

FIG. 2.

rAAV transduction in DU145 cells overexpressing either the full-length or the intracellular domain of Notch1. (A) DU145 and DU145 clones overexpressing either full-length or intracellular Notch1 were transduced with 100 MOI of rAAV2 luciferase in triplicate. The cells were harvested 48 h after transduction and luciferase activity determined. Relative light units (RLU) as a measure of luciferase activity were normalized to the protein content in each lysate (*, P < 0.02 compared to the luciferase activity in DU145 cells). (B) Semiquantitative real-time PCR was performed with DNA isolated from DU145 cells or DU145 cells overexpressing full-length or intracellular Notch1. The values shown represent the increase (n-fold) in vector copy number per cell from each clone compared to that from DU145 cells.

Functional characterization of Notch1 with fluorescently labeled virus.

In the next step, fluorescently labeled rAAV2 green fluorescent protein (GFP) was produced to study viral intracellular trafficking and was used to infect replicate cultures of HeLa, DU145, DU145-hN1, and DU145-hN1IC clones either at 4°C or at 37°C. The cells were fixed at different time points (0.5, 1, and 2 h) and analyzed by confocal microscopy. The results of these studies are provided in Fig. 3A. In all cell types, Cy3-labeled virus was found to bind to the cell surface at 4°C. When incubation was continued at 37°C, internalization of the virus and nuclear trafficking were seen in HeLa, DU145-hN1, and DU145-hN1IC cells. There was also a larger amount of internalized vector in DU145-hN1IC cells than in DU145-hN1 cells. However, there was very minimal vector internalization in unmodified DU145 cells. After 0.5 h of incubation at 37°C, the majority of internalized virus in permissive cells was found in the cytoplasm and a few virus particles were localized in the nuclei. Almost half of the virus particles were localized in the nuclei after 1 h of incubation at 37°C and by 2 h at 37°C; most of the virus particles were accumulated in the nuclear area, as detected by counterstaining with Hoechst 33258 (Fig. 3B). However, such vector entry or nuclear trafficking was not observed in the parental DU145 cells even after 2 h of incubation at 37°C. Inhibition of proteasomal degradation did not augment Notch1 enhancement of rAAV2 transduction (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Transduction of Cy3-labeled rAAV2 GFP in DU145 cells overexpressing Notch1. (A) Time course analysis of Cy3-labeled AAV2 intracellular trafficking. DU145, DU145-hN1, DU145-hN1IC, and HeLa cells were incubated with Cy3-labeled rAAV2 at 4°C for binding. The cells were either washed and fixed after 1 h or shifted to 37°C for 0.5, 1, or 2 h prior to fixation. Tracking of virus binding and intracellular trafficking were analyzed by confocal microscopy. (B) Nuclear accumulation of Cy3-labeled rAAV2. Cells were counterstained with Hoechst 33258 after 2 h of incubation at 37°C to demonstrate nuclear accumulation of the viral particles.

Role of dynamin in Notch1-regulated rAAV2 transduction enhancement.

Proteolytic cleavage of full-length Notch1 to an active, intracellular form is mediated in part by dynamin. To establish whether low abundance of Notch1, correlating with lower rAAV2 transduction, is due to insufficient expression of dynamin, the amounts of dynamin in HeLa, DU145, DU145hN1, DU145hN1IC, and 293 cells were determined by Western blot analysis. The results, shown in Fig. 4A, indicated comparable amounts of dynamin expression between all cell types and that the small amount of Notch in DU145 cells was not because of the absence of dynamin. To further determine whether the influence of Notch1 in enhancing rAAV2 transduction was dependent on dynamin function, a dominant-negative dynamin mutant was overexpressed using a recombinant adenovirus vector (9). As shown in Fig. 4B, it was interesting to note that blocking dynamin function greatly inhibited rAAV2 transduction only in DU145hN1 clones and not in DU145-hN1IC clones, confirming that the proteolytically cleaved intracellular form of Notch1 is responsible for the observed rAAV transduction enhancement.

FIG. 4.

Dynamin expression in different cell lines and rAAV2 transduction following blocking of dynamin function. (A) Equal amounts of protein from lysates from indicated cells were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and detected using antibody for human dynamin. The same blot was rehybridized with β-actin antibody to confirm the quantity of protein in each lane. (B) Dynamin function in DU145hN1 and DU145hN1IC cells was blocked by transducing rAd encoding a dominant-negative dynamin mutant, after which the cells were transduced with rAAV2 luciferase. Luciferase activity was determined 48 h later from cell lysates and normalized to protein concentration. The data from each cell line are represented as the percentage of luciferase activity compared to rAAV2 luciferase transduction without dynamin blocking.

Collectively, these studies provide evidence that Notch1 plays a significant role in nuclear trafficking of rAAV2 and that modulation of Notch expression may give additional options for increasing AAV2 gene transfer efficiency in target cells, with limitations in AAV trafficking and/or nuclear transport of the vector.

Acknowledgments

The financial support of the National Institutes of Health grants CA98817 and AR050251 and the U.S. Army Department of Defense grants PC020372 and PC050949 is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 6 December 2006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Artavanis-Tsakonas, S., K. Matsuno, and M. E. Fortini. 1995. Notch signaling. Science 268:225-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baron, M., H. Aslam, M. Flasza, M. Fostier, J. E. Higgs, S. L. Mazaleyrat, and M. B. Wilkin. 2002. Multiple levels of Notch signal regulation. Mol. Membr. Biol. 19:27-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartlett, J. S., R. Wilcher, and R. J. Samulski. 2000. Infectious entry pathway of adeno-associated virus and adeno-associated virus vectors. J. Virol. 74:2777-2785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blaumueller, C. M., H. Qi, P. Zagouras, and S. Artavanis-Taskonas. 1997. Intracellular cleavage of Notch leads to a heterodimeric receptor on the plasma membrane. Cell 90:281-291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carter, B. J. 2005. Adeno-associated virus vectors in clinical trials. Hum. Gene Ther. 16:541-550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang, H. 2006. Notch signal transduction induces a novel profile of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus gene expression. J. Microbiol. 44:217-225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang, H., D. P. Dittmer, Y. C. Shin, Y. Hong, and J. U. Jung. 2005. Role of Notch signal transduction in Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus gene expression. J. Virol. 79:14371-14382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi, V. W., D. M. McCarty, and R. J. Samulski. 2005. AAV hybrid serotypes: improved vectors for gene delivery. Curr. Gene Ther. 5:299-310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duan, D., Q. Li, A. W. Kao, Y. Yue, J. E. Pessin, and J. F. Engelhardt. 1999. Dynamin is required for recombinant adeno-associated virus type 2 infection. J. Virol. 73:10371-10376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farrell, C. J., J. M. Lee, E. C. Shin, M. Cebrat, P. A. Cole, and S. D. Hayward. 2004. Inhibition of Epstein-Barr virus-induced growth proliferation by a nuclear antigen EBNA2-TAT peptide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:4625-4630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayward. S. D. 2004. Viral interactions with the Notch pathway. Semin. Cancer Biol. 14:387-396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lan, K., T. Choudhuri, M. Murakami, D. A. Kuppers, and E. S. Robertson. 2006. Intracellular activated Notch1 is critical for proliferation of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-associated B-lymphoma cell lines in vitro. J. Virol. 80:6411-6419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qing, K., C. Mah, J. Hansen, S. Zhou, V. Dwarki, and A. Srivastava. 1999. Human fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 is a co-receptor for infection by adeno-associated virus 2. Nat. Med. 5:71-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rangarajan, A., R. Syal, S. Selvarajah, O. Chakrabarti, A. Sarin, and S. Krishna. 2001. Activated Notch1 signaling cooperates with papillomavirus oncogenes in transformation and generates resistance to apoptosis on matrix withdrawal through PKB/Akt. Virology 286:23-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Samulski, R. J., K. I. Berns, M. Tan, and N. Muzyczka. 1982. Cloning of infectious adeno-associated virus into pBR322: rescue of intact virus from the recombinant plasmid in human cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 79:2077-2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanlioglu, S., P. K. Benson, J. Yang, E. M. Atkinson, T. Reynolds, and J. F. Engelhardt. 2000. Endocytosis and nuclear trafficking of adeno-associated virus type 2 are controlled by Rac1 and phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase activation. J. Virol. 74:9184-9196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sanlioglu, S., M. M. Monick, G. Luleci, G. W. Hunninghake, and J. F. Engelhardt. 2001. Rate limiting steps of AAV transduction and implications for human gene therapy. Curr. Gene Ther. 1:137-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seugnet, L., P. Simpson, and M. Haenlin. 1997. Requirement for dynamin during Notch signaling in Drosophila neurogenesis. Dev. Biol. 192:585-598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strutt, D., R. Johnson, K. Cooper, and S. Bray. 2002. Asymmetric localization of Frizzled and the determination of Notch-dependent cell fate in the Drosophila eye. Curr. Biol. 12:813-824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Summerford, C., and R. J. Samulski. 1998. Membrane-associated heparan sulfate proteoglycan is a receptor for adeno-associated virus type 2 virions. J. Virol. 72:1438-1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Summerford, C., J. S. Bartlett, and R. J. Samulski. 1999. AlphaVbeta5 integrin: a co-receptor for adeno-associated virus type 2 infection. Nat. Med. 5:78-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhong, L., L. Chen, Y. Li, K. Qing, K. A. Weigel-Kelley, R. J. Chan, M. C. Yoder, and A. Srivastava. 2004. Self-complementary adeno-associated virus 2 (AAV)-T cell protein tyrosine phosphatase vectors as helper viruses to improve transduction efficiency of conventional single-stranded AAV vectors in vitro and in vivo. Mol. Ther. 10:950-957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]