Abstract

Aminoglycosides bind to the 16S rRNA at the tRNA acceptor site (A site) and disturb protein synthesis by inducing codon misreading. We investigated Escherichia coli cell elongation and division, as well as the dynamics of chromosome replication and segregation, in the presence of sublethal concentrations of amikacin (AMK). The fates of the chromosome ori and ter loci were monitored by visualization by using derivatives of LacI and TetR fused to fluorescent proteins in E. coli strains that carry operator arrays at the appropriate locations. The results showed that cultures containing sublethal concentrations of AMK contained abnormally elongated cells. The chromosomes in these cells were properly located, suggesting that the dynamics of replication and segregation were normal. FtsZ, an essential protein in the process of cell division, was studied by using an ectopic FtsZ-cyan fluorescent protein fusion. Consistent with a defect in cell division, we revealed that the Z ring failed to properly assemble in these elongated cells.

Aminoglycosides are critical components of the armamentarium for the treatment of serious infections caused by gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria. For the latter types of infections, they are usually used in combination with β-lactams or vancomycin (22). Aminoglycoside antibiotics have played an important role in the treatment of infections caused by members of the family Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Acinetobacter spp., streptococci, and enterococci. Some aminoglycosides, like amikacin (AMK) and kanamycin, have been used as second-line drugs for the treatment of resistant Mycobacterium infections (25). In particular, AMK has been effective as part of treatments for patients with M. avium complex bacteremia (19) and for the treatment of infections caused by organisms resistant to the other aminoglycosides (21). Aminoglycosides are thought to penetrate the cells in a three-step process. Once they are inside the cytosol, they bind to the 16S rRNA at the tRNA acceptor site (A site), which plays an important role for the high fidelity of translation (12, 22), and act by interfering with the decoding process rather than by sterically hindering the tRNA-ribosome interaction (10). The recent resolution of complexes between aminoglycoside molecules and rRNA or oligonucleotides has improved our understanding of the physicochemical basis of the interactions between the aminoglycosides and the RNA molecules (4-7, 17, 23, 26). However, although it is accepted that most aminoglycosides exert their action through the induction of misreading during protein synthesis, the precise mechanisms and effects of their antimicrobial activities are still poorly understood (14, 22). A series of metabolic perturbations, such as disturbances in DNA and RNA synthesis, as well as altered membrane composition, permeability, and cellular ionic concentrations, have been described; but most of them can be secondary to the presence of mistranslated proteins (for reviews, see reference 3 and 14). To recognize cell processes that are especially susceptible to the presence of aminoglycosides and better understand their mechanisms of action, we carried out a cell biology approach to examining cell elongation and division as well as the dynamics of chromosome replication and segregation in Escherichia coli cells growing in the presence of sublethal concentrations of AMK. Our results showed that sublethal concentrations of AMK had an effect on cell division, as judged by a high number of elongated cells with a correct distribution of the ori and ter loci, suggesting that the dynamics of chromosome replication and segregation were normal.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

Escherichia coli IL05 is strain AB1157 with a lacO array (240 copies) 210 kbp clockwise from dif (ter-2) and a tetO array (240 copies) 15 kbp counterclockwise from oriC (11, 24). Escherichia coli IL06 is strain AB1157 with a lacO array (240 copies) 15 kbp counterclockwise from oriC, a tetO array (240 copies) 15 kbp counterclockwise from oriC, and a tetO array (240 copies) 50 kbp clockwise from dif (ter-3) (11, 24). Both strains carry plasmid pWX6, which includes genes that code for the fusions LacI-cyan fluorescent protein (CFP) and TetR-yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) under the control of a weak constitutive promoter, PftsKi (24). Escherichia coli IL06 harboring pCP12, a plasmid that codes for FtsZ-CFP and LacI-YFP under the control of PftsKi (24), was used to visualize FtsZ and ori.

Microscopy.

Cells were grown at 37°C in M9-sodium acetate medium supplemented with the amino acids required for AB1157 growth and 100 μg/ml ampicillin, the plasmid-selecting drug. The doubling time of the cells growing under these conditions while they are in exponential phase is about 3 h. Since excessive repressor binding is detrimental, 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside and 40 ng/ml anhydrotetracycline were added to reduce the binding of the fluorescent LacI and TetR, respectively, without compromising the ability to observe sharp fluorescent foci. The indicated concentrations of AMK were added when the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) reached 0.05. After 14 h (late exponential phase) the cells were transferred to a layer made of 1% agarose in phosphate-buffered saline solution for analysis by microscopy. Aliquots were plated on L agar, and viability was estimated. The cells were visualized with a ×100 objective on a Nikon Eclipse TE2000-U microscope equipped with a Photometrics Cool-SNAP HQ charge-coupled-device camera and a temperature-controlled incubation chamber. The images were taken, analyzed, and processed by using MetaMorph 6.2 and Adobe Photoshop software. Phase-contrast microscopy for visualization of nucleoids and inclusion bodies was carried out in 27% gelatin-containing minimal medium as described before (16, 24; H. Niki, personal communication).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Low AMK concentrations affect cell physiology without significantly interfering with viability.

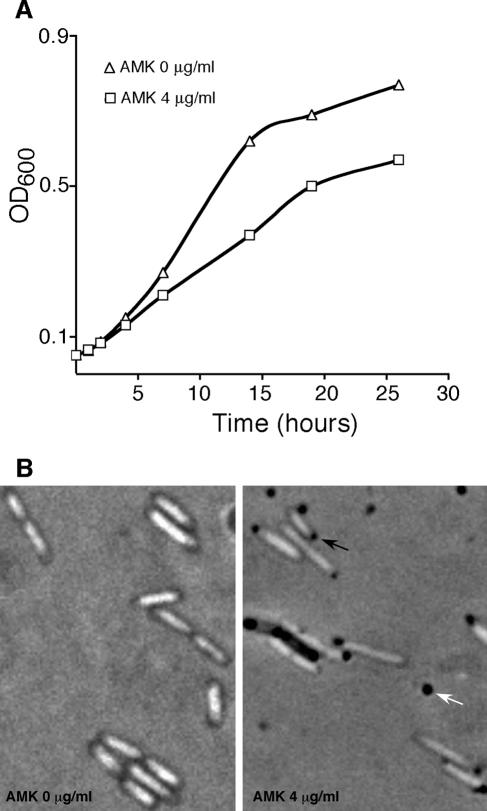

We initiated a project to study the effects of AMK on different E. coli cellular processes while the cells were growing in liquid minimal medium. To discriminate the cell processes most susceptible to the action of AMK, we used conditions of a slow growth rate and AMK concentrations that did not significantly affect the growth or viability of the cells. AMK concentrations exceeding 16 μg/ml resulted in the quick loss of viability, as determined by OD600 determination and plating on L agar after 8 h of incubation. However, at lower AMK concentrations (4 μg/ml), growth continued after 14 h of incubation (late logarithmic phase) (Fig. 1A), and the plating efficiency on L agar showed that there was no significant loss of viability within this time. However, the sizes and the numbers of colonies on 4 μg/ml AMK-containing L-agar plates after overnight incubation were reduced compared to those of colonies growing on plain L-agar plates, indicating that there is a deleterious effect that can be detected after a higher number of generations.

FIG. 1.

Analysis of E. coli IL05(pWX6) cells growing in the presence or the absence of 4 μg/ml AMK. (A) Growth curves; (B) cells visualized after 14 h in the presence of gelatin, as described in Materials and Methods. Under these conditions the nucleoids appear as light masses inside the cells. Arrows indicate inclusion body-like formations inside the cells (black arrow) or in the medium (white arrow).

Figure 1B shows a comparison of cells grown in the absence and the presence of 4 μg/ml AMK. In both cases nucleoids can be observed as light masses, but granular bodies at the poles are only seen in the presence of the antibiotic. We suspect that these granular bodies, reminiscent of inclusion bodies, are proteinaceous (8), but we do not know if they contain one or more proteins. Almost all cells in the cultures containing 4 μg/ml AMK possessed the granular bodies. These results suggest that although 4 μg/ml AMK is a sublethal concentration, it is enough to interfere with proper protein translation. The presence of some granular bodies in the medium and cells lacking nucleoid (as determined by the absence of a light mass inside the cell) may indicate a certain level of cell lysis at this AMK concentration.

Low AMK concentrations affect cell division without significantly interfering with chromosome replication and segregation.

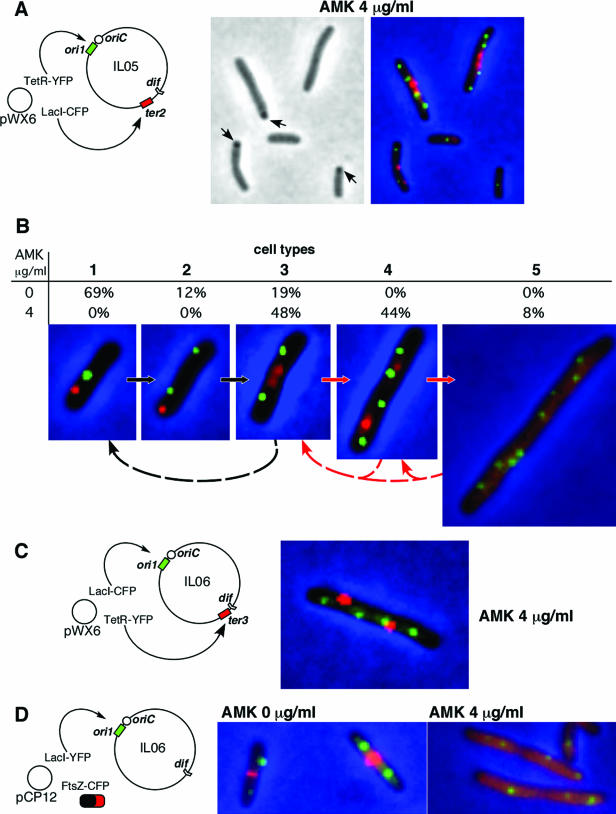

The fate of the chromosome ori and ter loci in growing E. coli cells can be followed by fluorescence microscopy by using derivatives of LacI and TetR fused to fluorescent proteins. Genes coding for both fluorescent repressors are included in plasmid pWX6 and are expressed in tandem from a weak constitutive promoter. The fluorescent repressors bind to operator arrays which have been inserted at the appropriate locations of the E. coli chromosome (strains IL05 and IL06; see Materials and Methods) and to which the fluorescent repressors bind (24). When the cells are cultured by using the appropriate conditions, the modifications done to the cells to track the regions close to ori and ter do not interfere significantly with the process under analysis (11, 18, 24). The cartoons in Fig. 2 show the regions in the chromosome where the operator arrays have been inserted.

FIG. 2.

Effects of sublethal concentrations of AMK on chromosome dynamics and Z-ring assembly. The cartoons show circular E. coli chromosomes indicating the target regions and the plasmids coding for fusion proteins. For simplicity, regardless of the nature of the fluorescent protein, the foci corresponding to the ori regions have been colored green. Fluorescent signals indicating the ter region or the FtsZ protein have been colored red. (A) E. coli IL05(pWX6) cells cultured in the presence of 4 μg/ml AMK examined under phase contrast only (left) or the overlay of phase contrast and CFP and YFP fluorescence signals. (B) Representative E. coli IL05(pWX6) cells of the five types found under different growth conditions (with 0, 4, 8, 16, or 32 μg/ml AMK). Although the distribution of cell types is described in Table 1, this figure also shows the values for 0 and 4 μg/ml AMK. The proposed progression of the cell cycle in the absence and the presence of AMK is shown by the black and the red arrows, respectively. Dashed arrows indicate the stages at which cell division may occur. (C) E. coli IL06(pWX6) cultured in the presence of 4 μg/ml AMK (see text). (D) E. coli IL06(pCP12) cultured in the absence or the presence of 4 μg/ml AMK.

To understand the degrees to which AMK affects cellular processes such as chromosome replication and segregation, as well as cell elongation and division, we compared E. coli IL05 cells cultured in the absence of AMK with IL05 cells cultured in the presence of 4 μg/ml AMK (Fig. 2A and B). A typical field showing cells cultured in the presence of the antibiotic for 14 h is shown in Fig. 2A. Examining the phase-contrast image, one can observe some inclusion bodies in cells of normal or larger-than-normal size, and all exhibit fluorescence signals indicative of the ori and ter locus positions within the cells. Figure 2B shows the different cell types that are present in exponentially growing cultures in the absence or presence of AMK. These cells are representative of groups defined on the basis of the number of ori and ter loci, which appear as well-defined foci. Each one of these groups corresponds to a stage in the cell cycle; and the proportion of each of these groups, reflecting the duration of the stage as well as the average cell length, are also shown in Table 1 (24). In these slowly growing cultures without AMK, the cell cycle (Fig. 2B, black arrows) is composed of three main cell types: newborn cells containing one ori focus and one ter focus (Fig. 2B, cell type 1); cells with duplicated sister ori foci (Fig. 2B, cell type 2); and cells with duplicated ter foci, a stage prior to initiation of cell division (Fig. 2B, cell type 3).

TABLE 1.

Distribution of cell types at various AMK concentrations

| AMK concn (μg/ml) | % (avg cell length [μm]) of the following cell types (no. of foci)a:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (one ori, one ter) | 2 (two ori, one ter) | 3 (two ori, two ter) | 4 (four ori) | 5 (eight ori) | |

| 0 | 69 (1.4 ± 0.2) | 12 (1.7 ± 0.2) | 19 (2.1 ± 0.2) | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 48 (1.8 ± 0.3) | 44 (2.8 ± 0.4) | 8 (4.4 ± 0.5) |

| 8 | 0 | 0 | 36 (1.8 ± 0.3) | 69 (2.6 ± 0.4) | 5 (4.3 ± 0.5) |

| 16 | 6 (1.4 ± 0.2) | 3 (1.4 ± 0.2) | 34 (1.8 ± 0.3) | 46 (2.5 ± 0.5) | 11 (3.8 ± 0.4) |

| 32b | 32 (1.3 ± 0.2) | 37 (1.6 ± 0.2) | 31 (2.0 ± 0.2) | 0 | 0 |

Percentage of cell types (1 through 5), as defined by the number of ori and ter foci (shown in Fig. 2), when E. coli IL05(pWX6) was cultured in the presence of the indicated concentrations of AMK for 14 h. Two hundred cells per culture from one set of experiments were used to generate the data for this table, and comparable results were observed from three independent experiments.

In these cultures, a substantial number of cells that did not show fluorescence were also detected but not counted.

Addition of 4 or 8 μg/ml AMK did not modify significantly the cell population for at least 8 h (not shown). However, after 14 h, the cell population under these conditions was characterized by the lack of cells of types 1 and 2 (Table 1) and the presence of a substantial number of anomalous cells types characterized by their longer than normal size and the presence of four or eight ori foci (Fig. 2A and B, cell types 4 and 5). Table 1 shows the distribution of cell types in cultures carried out in the presence of 4 or 8 μg/ml AMK; more than half of the cells were of type 4 or 5. Figure 2B (red arrows) also shows the proposed cell cycle under these conditions; within the time frame of this experiment cell division may be delayed (Fig. 2B, dashed red arrows).

As stated above, the presence of a lethal AMK concentration (32 μg/ml) in the cultures precluded any cell growth, and analysis of the cell types showed cell debris and cells of types 1 to 3, i.e., no modification with respect to the profiles observed in the absence of AMK (Table 1). This may be because at this AMK concentration all cell functions stopped immediately upon addition of the antibiotic. In the presence of 16 μg/ml we observed a cell population that was intermediate between the situations for cultures growing in the presence of 8 and 32 μg/ml AMK (Table 1).

Equivalent results were obtained when the same experiments were carried out with E. coli IL06, a strain in which the operator arrays have been inverted with respect to those in strain IL05 (Fig. 2C).

The results discussed in this section indicate that the presence of AMK at certain concentrations that are low enough not to be lethal results in the formation of inclusion body-like formations and that AMK interferes with cell division, while DNA replication and segregation appear to proceed normally.

Low AMK concentrations affect assembly of the Z ring.

A key element in the process of cell division is FtsZ, a tubulin-like protein that assembles into a proteofilament to form a structure known as the Z ring, which defines the position where cell division will take place (1, 13). Assembly of the Z ring occurs at about the same time that chromosome replication terminates, followed by invagination of the septal wall, leading to cell division (15). Since cell division was affected in the presence of low concentrations of AMK, we investigated the behavior of FtsZ under these conditions. Cells harboring a plasmid coding for an FtsZ-CFP fusion were cultured in the presence or the absence of AMK. To compare the ability of the Z ring to form under both conditions, we analyzed a subset of the population consisting of about 200 cells containing two origins of replication from each culture. As expected, a clear red Z ring was observed in a large percentage (88%) of the cells growing in the absence of the antibiotic (Fig. 2D). Conversely, in the presence of AMK the percentage of cells with the Z ring was lower (35%). In those cells not showing a Z ring, the red FtsZ-CFP signal was homogeneously distributed throughout the cytoplasm (Fig. 2D), indicating impairment in the formation of the Z ring. In agreement with the experiments described above, cells growing in the presence or the absence of AMK showed normal origin dynamics (see the green ori foci in Fig. 2D). These results suggest that the presence of sublethal concentrations of AMK prevents FtsZ from forming the Z ring and, therefore, from playing its crucial role in cell division. However, since the formation of the Z ring requires not only functional FtsZ proteins but also many other essential structural and regulator proteins, such as SulA, MinC, MinD, and MinE (2, 9), we do not yet know if the inhibition of Z-ring formation is exclusively due to the mistranslation of FtsZ or if it is due to the mistranslation of some or all of the proteins involved. We are carrying out experiments to determine the effects of sublethal concentrations of AMK on other cell division proteins, including those that follow FtsZ in the assembly of the divisome (20). Although it is highly unlikely, it is worth mentioning that there could be an effect of AMK binding to FtsZ and preventing it from forming the Z ring.

Concluding remarks.

Important advances in the understanding of molecular interactions and mechanisms of action have been made with the resolution of the crystal structures of complexes between aminoglycoside molecules and rRNA or oligonucleotides (4-7, 17, 23, 26). We have started a program that uses a cell biology approach to understand how aminoglycosides affect different cellular processes within bacteria. Our data show that not all cellular processes are equally susceptible to the action of AMK. Cell division was affected by sublethal concentrations of AMK, while the chromosomal dynamics seemed to be more resilient. In the presence of sublethal AMK concentrations, replication as well as segregation of the ori and the ter loci seemed to be unaffected. We showed here that this approach might be an important tool in the clarification of the mechanisms of action of aminoglycosides at the cellular level.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by Public Health Service grant AI47115-02 (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health) (to M.E.T.), LA Basin Minority Health and Health Disparities International Research Training Program (MHIRT) grant 5T37MD001368-09 (National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities), and a grant from Wellcome Trust (to D.J.S.). J.N. was supported by grant R25 GM56820-03 (MSD) and MIRT grant 5T37TW000048-07 from the National Institutes of Health. N.S. was supported by grant 5T37MD001368-09 from the National Center for Minority Health and Health Disparities, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 16 October 2006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bi, E., and J. Lutkenhaus. 1991. FtsZ ring structure associated with division in Escherichia coli. Nature 354:161-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cordell, S. C., E. J. Robinson, and J. Lowe. 2003. Crystal structure of the SOS cell division inhibitor SulA and in complex with FtsZ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:7889-7894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis, B. D. 1987. Mechanism of bactericidal action of aminoglycosides. Microbiol. Rev. 51:341-350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fourmy, D., M. I. Recht, S. C. Blanchard, and J. D. Puglisi. 1996. Structure of the A site of Escherichia coli 16S ribosomal RNA complexed with an aminoglycoside antibiotic. Science 274:1367-1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fourmy, D., M. I. Recht, and J. D. Puglisi. 1998. Binding of neomycin-class aminoglycoside antibiotics to the A-site of 16 S rRNA. J. Mol. Biol. 277:347-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fourmy, D., S. Yoshizawa, and J. D. Puglisi. 1998. Paromomycin binding induces a local conformational change in the A-site of 16S rRNA. J. Mol. Biol. 277:333-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Francois, B., R. Russell, J. Murray, F. Aboul-ela, B. Masquida, Q. Vicens, and E. Westhof. 2005. Crystal structures of complexes between aminoglycosides and decoding A site oligonucleotides: role of the number of rings and positive charges in the specific binding leading to miscoding. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:5677-5690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Georgiou, G., P. Valax, M. Ostermeier, and P. M. Horowitz. 1994. Folding and aggregation of TEM beta-lactamase: analogies with the formation of inclusion bodies in Escherichia coli. Protein Sci. 3:1953-1960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goehring, N. W., M. D. Gonzalez, and J. Beckwith. 2006. Premature targeting of cell division proteins to midcell reveals hierarchies of protein interactions involved in divisome assembly. Mol. Microbiol. 61:33-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hobbie, S., P. Pfister, C. Bruell, P. Sander, B. Francois, E. Westhof, and E. Bottger. 2006. Binding of neomycin-class aminoglycoside antibiotics to mutant ribosomes with alterations in the A site of 16S rRNA. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:1489-1496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lau, I., S. Filipe, B. Søballe, O. Økstad, F. Barre, and D. J. Sherratt. 2003. Spatial and temporal organization of replicating Escherichia coli chromosomes. Mol. Microbiol. 49:731-743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lodmell, J. S., and A. E. Dahlberg. 1997. A conformational switch in Escherichia coli 16S ribosomal RNA during decoding of messenger RNA. Science 277:1262-1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lutkenhaus, J., and S. Addinall. 1997. Bacterial cell division and the Z ring. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 66:93-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Magnet, S., and J. S. Blanchard. 2005. Molecular insights into aminoglycoside action and resistance. Chem. Rev. 105:477-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Margolin, W. 2005. FtsZ and the division of prokaryotic cells and organelles. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6:862-871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mason, D. J., and D. M. Powelson. 1956. Nuclear division as observed in live bacteria by a new technique. J. Bacteriol. 71:474-479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ogle, J. M., A. P. Carter, and V. Ramakrishnan. 2003. Insights into the decoding mechanism from recent ribosome structures. Trends Biochem. Sci. 28:259-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Possoz, C., S. R. Filipe, I. Grainge, and D. J. Sherratt. 2006. Tracking of controlled Escherichia coli replication fork stalling and restart at repressor-bound DNA in vivo. EMBO J. 25:2596-2604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roger, P. M., M. Carles, I. Agussol-Foin, L. Pandiani, O. Keita-Perse, V. Mondain, F. De Salvador, and P. Dellamonica. 1999. Efficacy and safety of an intravenous induction therapy for treatment of disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex infection in AIDS patients: a pilot study. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 44:129-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rothfield, L., A. Taghbalout, and Y. L. Shih. 2005. Spatial control of bacterial division-site placement. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3:959-968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tolmasky, M. E., M. Roberts, M. Woloj, and J. H. Crosa. 1986. Molecular cloning of amikacin resistance determinants from a Klebsiella pneumoniae plasmid. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 30:315-320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vakulenko, S. B., and S. Mobashery. 2003. Versatility of aminoglycosides and prospects for their future. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 16:430-450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vicens, Q., and E. Westhof. 2003. Molecular recognition of aminoglycoside antibiotics by ribosomal RNA and resistance enzymes: an analysis of X-ray crystal structures. Biopolymers 70:42-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang, X., C. Possoz, and D. J. Sherratt. 2005. Dancing around the divisome: asymmetric chromosome segregation in Escherichia coli. Genes Dev. 19:2367-2377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yao, J., and R. Moellering. 2003. Antibacterial agents, p. 1031-1073. In P. Murray, E. Baron, J. Jorgensen, M. Pfaller, and R. Yolken (ed.), Manual of clinical microbiology, vol. 1, 8th ed. ASM Press, Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoshizawa, S., D. Fourmy, R. G. Eason, and J. D. Puglisi. 2002. Sequence-specific recognition of the major groove of RNA by deoxystreptamine. Biochemistry 41:6263-6270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]