Abstract

The distribution, metabolism, and excretion of CS-023 (RO4908463), a new carbapenem, were investigated in rats and monkeys after a single intravenous administration of [14C]CS-023. In addition, the drug's pharmacokinetics were examined in rats, dogs, and monkeys. Whole-body autoradioluminograms of rats indicated that the radioactivity is distributed throughout the body immediately after administration except for the central nervous system and testes. The highest radioactivity was found in the kidneys, which are responsible for the excretion of CS-023. R-131624 with an open β-lactam ring, the pharmacologically inactive form, was detected in the plasma and urine as the major metabolite. In rat plasma, the R-131624 levels became higher than CS-023 levels at 30 min postdose and thereafter, while in monkey plasma, CS-023 accounted for most of the radioactivity, with low levels of R-131624. More than 80% of the radioactivity administered was recovered in the urine, and CS-023 and R-131624 accounted for 29.6% and 31.4%, respectively, of the dose in rats and 51.2% and 18.5%, respectively, of the dose in monkeys. The faster metabolism to R-131624 in rats than in monkeys was likely due to the metabolism by dehydropeptidase I in rat lungs. The plasma elimination half-life of CS-023 was 0.16 h in rats, 0.75 h in dogs, and 1.4 h in monkeys. There were no appreciable interspecies differences among the animals tested in either volume of distribution (172 to 259 ml/kg) or serum protein binding (5.0 to 15.6%). The total clearance in monkeys (1.62 ml/min/kg) was lower than that in rats (15.1 ml/min/kg) or dogs (4.19 ml/min/kg).

Carbapenems for injection, imipenem-cilastatin (5), panipenem-betamipron (marketed only in Japan) (4), meropenem (18), biapenem (marketed only in Japan) (12), and ertapenem (10), have been introduced into the market during the last 2 decades. In the development of new carbapenem antibiotics, much effort has been made to maintain drug concentrations in plasma. Although imipenem and panipenem need to be administered with a codrug such as cilastatin to prevent degradation by the enzyme dehydropeptidase I (DHP-I) and/or to reduce nephrotoxicity, the newer drugs such as meropenem, ertapenem, and biapenem are permitted to be administered without coadministration of inhibitors because of their greater resistance to degradation by DHP-I and their low renal toxicity. However, the half-lives of these carbapenems are still around 1 h in humans, except for ertapenem. Ertapenem (15) has a prolonged plasma half-life of about 5 h, largely due to decreased renal clearance, which likely results from a high serum protein binding of more than 95%. This characteristic distinguishes ertapenem from all other carbapenems, which exhibit low protein-binding ratios of around 10%.

CS-023 (RO4908463, formerly R-115685) is a new 2-substituted 1β-methyl carbapenem that has a unique guanidine-pyrrolidine side chain and binds with high affinity to penicillin-binding protein 1 (PBP1), PBP2, and PBP4 from Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 6538P and PBP1A, PBP1B, PBP2, and PBP3 from Escherichia coli NIHJ (9). CS-023 has broad-spectrum activity against gram-positive and -negative bacteria, including clinically important pathogens such as methicillin-resistant S. aureus, penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, members of the family Enterobacteriaceae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. (6, 7, 17). In clinical pharmacokinetic studies with healthy volunteers, CS-023 was well tolerated following a 30-min intravenous infusion at doses of up to 2,100 mg and showed a plasma half-life of 1.5 to 2.0 h (13). The cumulative urinary excretion rate of the intact form reached 52 to 70% of the dose. CS-023 is currently under extensive clinical evaluation, phase I in Japan and phase II in Europe and the United States, and its potent efficacy for respiratory tract and urinary tract infections and safety are to be demonstrated in patients.

In this study, we investigated the distribution, metabolism, and excretion of CS-023 after intravenous administration of [14C]CS-023 (Fig. 1) to rats and monkeys. In addition, the plasma concentration-time profile after intravenous administration of CS-023 and serum protein binding were examined in rats, dogs, and monkeys. These data provide fundamental information on the pharmacokinetics of CS-023 in animals to predict human pharmacokinetics.

FIG. 1.

Chemical structures of [14C]CS-023 and R-131624. *, 14C-labeled position.

(Part of this work was presented at the 40th International Conference on Antibacterial Agents and Chemotherapy, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 17 to 20 September 2000 [T. Shibayama, Y. Matsushita, K. Kikuchi, K. Kawai, T. Hirota, and S. Kuwahara, Abstr. 40th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. F-1233, 2000]).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Test substances and chemicals.

CS-023 and R-131624 (Fig. 1) were synthesized at Sankyo Research Laboratories. [14C]CS-023 was synthesized at Daiichi Pure Chemicals Co., Ltd. (Ibaraki, Japan). The specific radioactivity was 916 kBq/mg, and the radiochemical purity was determined to be more than 97%. 3-Morpholinopropanesulfonic acid (MOPS), used to stabilize CS-023 in biological fluid, and p-acetamidophenol, used as an internal standard for high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis, were purchased from Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd. (Osaka, Japan). The other reagents and solvents used were commercially available and of either extrapure or guaranteed grade.

Animals.

Male Sprague-Dawley rats 6 weeks old and weighing 234 to 260 g (Charles River Japan, Inc., Yokohama, Japan), male cynomolgus monkeys 4 years old and weighing 3.7 to 4.4 kg (SLC Japan Inc., Hamamatsu, Japan), and male beagle dogs weighing approximately 11 kg (Nihon Nosan Kogyo K.K., Yokohama, Japan) were used in this study. The animals were kept in a room with a constant temperature (23 ± 2°C) and an automatically controlled 12-h light-dark cycle. All animal experiments were carried out according to the guidelines provided by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Sankyo Co., Ltd.

Disposition study using [14C]CS-023. (i) Drug administration.

[14C]CS-023 and nonlabeled CS-023 were dissolved in saline. The dosing solutions were intravenously administered to rats via the tail vein at a single bolus dose of 10 mg/2 ml/kg (4.58 MBq/kg for sample collection of plasma, urine, and feces and 9.16 MBq/kg for whole-body autoradioluminography) and to monkeys via the cephalic vein at a dose of 10 mg/ml/kg (3 MBq/kg).

(ii) Plasma sampling.

Blood samples were collected with heparinized syringes from the jugular veins of rats and from the femoral veins of monkeys at predetermined times after drug administration. The blood samples were immediately centrifuged at 4°C to obtain plasma samples. After aliquots were taken from each plasma sample for radioactivity measurement, an aliquot of plasma was mixed with the same volume of 0.2 M MOPS buffer (pH 6.0) for rat plasma or 0.1 M MOPS buffer (pH 6.0) for monkey plasma. To the mixture was added a fourfold volume of acetonitrile for rat plasma or a twofold volume of acetonitrile for monkey plasma. After centrifugation at 4°C, the supernatant was stored frozen at −20°C until analysis by thin-layer chromatography (TLC).

(iii) Collection of urinary and fecal samples.

Rats were housed individually in glass metabolic cages (Metabolica; Sugiyama-Gen Iriki Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) after dosing for separate collection of urine and feces over a 7-day period. Urine and feces samples were collected at up to 24 h postdose at around 4°C. For each urine collection at up to 24 h, a 3-ml aliquot of 0.5 M MOPS buffer (pH 6.0) was added to the urine receptacle. Fecal samples collected at up to 24 h postdose or those collected thereafter were added to ca. 20 ml of 0.5 M MOPS buffer (pH 6.0) or distilled water, which had been chilled at around 4°C, and were homogenized. Aliquots were taken from the urine samples and the fecal homogenates for measurement of radioactivity, and the remaining samples were stored frozen at −80°C until analysis by TLC.

Monkeys were housed individually in metabolic cages (Daiichi Pure Chemicals Co., Ltd., Ibaraki, Japan) after dosing for separate collection of urine and feces over a 7-day period. A 50-ml aliquot of 0.5 M MOPS buffer (pH 6.0) was added to each of the urine receptacles cooled at around 4°C. Fecal samples were added to 0.2 M MOPS buffer (pH 6.0) up to 300 to 500 ml and homogenized. Aliquots were taken from the urine samples and the fecal homogenates for measurement of radioactivity, and the remaining samples were stored frozen at −80°C until analysis by TLC.

(iv) Bile duct cannulation of rats for collection of bile.

Rats received a laparotomy for bile duct cannulation with a polyethylene tube (SP31; Natsume Seisakusho Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) under diethyl ether anesthesia (19). The bile fistula rats were individually housed in Bollman cages and dosed. Each bile sample was collected under constant cooling with ice for predetermined periods in a bile receptacle.

(v) Measurement of radioactivity.

An aliquot of a plasma, urine, bile, or fecal homogenate sample prepared as described above was put into a vial. To this were added 1 ml or 2 ml of a tissue solubilizer (NCS-II [Amersham International plc, Piscataway, NJ] or SOLUENE-350 [Packard Instrument Co., Downers Grove, IL]) and around 10 ml of liquid scintillation fluid (HIONIC-FLUOR or PICO-FLUOR; Packard Instrument Co.). The radioactivity in each sample was measured by a liquid scintillation counter (2300TR or 2500TR; Packard Instrument Co.). The limit of radioactivity quantitation was set at twice the background level.

(vi) Analysis of CS-023 and its metabolites by TLC.

An aliquot of a plasma, urine, or fecal homogenate sample was spotted onto a TLC plate (Silica Gel 60 F254, precoated, 0.25-mm thickness; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). The plate was developed with a mixture of a 3% sodium chloride solution and acetonitrile (2:1, vol/vol). After development, the plate was air dried completely and put in contact with an Imaging Plate (Fuji Photo Film Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) for about 24 h. The Imaging Plate was subjected to imaging analysis with a Bio-Imaging Analyzer (BAS 2000; Fuji Photo Film Co., Ltd.). The amounts of CS-023 and its metabolites in each sample were calculated by multiplying the radioactive proportions of the respective spots in TLC with the total radioactivity in each sample.

(vii) Whole-body autoradioluminography of rats.

Rats were sacrificed by deep anesthesia with diethyl ether at predetermined time points after drug administration. Each animal body was frozen in a liquid nitrogen bath and embedded in a gel containing 3% carboxymethyl cellulose sodium. Sagittal sections 50 μm thick were prepared from each frozen animal body with a Cryomacrocut (CM3600; Leica GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany). After drying, the sections were put in contact with Imaging Plates (Fuji Photo Film Co., Ltd.) for 24 h. Images of whole-body radioactivity distribution were generated with a Bio-Imaging Analyzer (BAS2000; Fuji Photo Film Co., Ltd.).

Pharmacokinetic study using nonlabeled CS-023. (i) Drug administration and blood sampling.

CS-023 as a solution in saline was intravenously administered to rats as a single bolus dose of 10, 25, or 50 mg/kg via the tail vein; to dogs at 5, 10, or 25 mg/kg via the saphenous vein of the foreleg; and to monkeys at 5, 10, or 25 mg/kg via the femoral vein of the lower limb. After dosing, blood samples were serially collected from rats via the jugular vein, from dogs via the saphenous vein of the foreleg, and from monkeys via the femoral vein.

(ii) Determination of CS-023 concentrations in plasma.

Concentrations of CS-023 in plasma were determined by HPLC. After blood collection, plasma was immediately separated from the blood sample by centrifugation at 4°C. To a 0.2-ml aliquot of plasma was added an equal volume of 500 mM MOPS buffer (pH 6.0) containing p-acetamidophenol (0.1 mg/ml). The mixture was vortexed and centrifuged at 4°C. A 10-μl aliquot of the supernatant was injected into an HPLC system (Shimadzu LC-10A system; Shimadzu Corp., Kyoto, Japan) which included two columns, a TSK gel G2000SW (300 mm by 7.5 mm [inside diameter]; TOSOH Corp., Tokyo, Japan) column as a clean-up column and a reversed-phase YMC-Pack ODSA A-312 (150 mm by 4.6 mm [inside diameter]; YMC Co., Ltd., Kyoto, Japan) column as an analytical column. The mobile phases used were 20 mM MOPS buffer (pH 6.0) for the clean-up column and a mixture of a 20 mM MOPS buffer (pH 7.0) and methanol (85/15, vol/vol) for the analytical column, each at a flow rate of 1.0 ml/min. UV detection was performed at 304 nm. Effluent from the clean-up column was introduced to the analytical column through a flow channel selection valve for an initial appropriate period after injection and was diverted to waste thereafter in order to avoid the peaks of proteins and other endogenous substances in the plasma being introduced into the analytical column. CS-023 was eluted at 26 min after sample injection.

Calibration standards were prepared by adding known amounts of CS-023 to blank plasma. There was a good linear relationship between the peak area ratio and the plasma concentration in the range of 1 to 500 μg/ml in rat and dog plasma and 2 to 500 μg/ml in monkey plasma. The assay bias ranged from 0.4 to 15%, and the coefficient of variation ranged from 0.8 to 10%.

(iii) Pharmacokinetic analysis.

Pharmacokinetic analysis was conducted by the noncompartmental method with the computer program WinNonlin (standard network edition, version 1.5; Scientific Consulting, Inc., Apex, NC). The elimination rate constant (kel) was determined as the slope of the linear regression line for the logarithmic plasma concentration versus time in the elimination phase. The elimination half-life (t1/2) was calculated according to the equation t1/2 = 0.693/kel. The area under the plasma concentration-time curve up to the last quantifiable sampling time (AUCt) was calculated by the trapezoidal method. AUC extrapolated to infinity (AUC0-∞) was calculated as follows: AUC0-∞ = AUCt + Clast/kel, where Clast is the concentration at the last quantifiable sampling time. Clearance of CS-023 from plasma (CL) was calculated by dividing the dose by the AUC0-∞. Renal clearance (CLR) was estimated by multiplying the CL value by the renal excretion ratio of CS-023. The volume of distribution at steady state (Vss) was estimated as the CL multiplied by the mean residence time.

Serum protein binding.

Serum protein-binding ratios of CS-023 were determined by a centrifugal ultrafiltration method (11). A 300-μl aliquot of serum was spiked with CS-023 (3 μl) in distilled water at a final concentration of 20 or 100 μg/ml, and the mixture was incubated for 5 min at 37°C. The mixture was transferred into a Centrifree centrifugal filter device (Millipore Co., Billerica, MA) and centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 10 min at room temperature. The concentrations of CS-023 in the serum sample before ultrafiltration and in the filtrate after ultrafiltration were determined by HPLC under the conditions described above. The serum protein-binding ratio (B, percent) was calculated according to the following equation: B = (Ct − Cf)/Ct × 100, where Ct is the concentration of CS-023 in serum before ultrafiltration and Cf is the concentration of CS-023 in the filtrate.

Statistical analysis.

For the parameters t1/2, CL, and Vss, a statistical test was carried out by a one-way analysis of variance or a mixed-effect model where appropriate (SAS System Release 8.2; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Tissue distribution of radioactivity in rats.

Typical whole-body autoradioluminograms after administration to rats are shown in Fig. 2.

FIG. 2.

Whole-body autoradioluminograms after a single intravenous administration of [14C]CS-023 at a dose of 10 mg/kg to rats. GI, gastrointestinal.

The radioactivity was distributed throughout the animal's body immediately after intravenous administration. On the other hand, there was little or no distribution to the central nervous system (the brain and spinal cord) or testes. At 15 min postdose, high radioactivity was detected in the urine, indicating rapid excretion in the urine. At 2 h postdose, apart from the kidneys, relatively high levels of radioactivity were observed in the lungs, the gastrointestinal tract, the liver, and the skin compared with that in the blood. The radioactivity in the body declined with time after administration and was observed only slightly in the kidneys and cecum at 24 h postdose. The highest radioactivity was found in the kidneys at all sampling times, indicating that the main excretion route is the urinary pathway. This observation was consistent with the high urinary recovery of the radioactivity in the mass balance study.

Metabolites in plasma. (i) Rats.

Plasma concentration-time profiles of total radioactivity, CS-023, and R-131624 are shown in Fig. 3A. Typical TLC autoradioluminograms of rat plasma are shown in Fig. 4.

FIG. 3.

Plasma concentration-time profiles after a single intravenous administration of [14C]CS-023 to rats (A) and monkeys (B) at a dose of 10 mg/kg. Each data point represents the mean ± the SD of three animals.

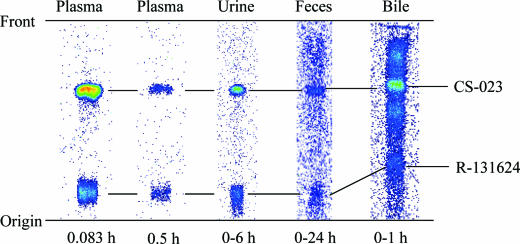

FIG. 4.

Typical TLC autoradioluminograms of radioactivity in plasma, urine, feces, and bile after a single intravenous administration of [14C]CS-023 to rats at a dose of 10 mg/kg.

The radioactivity in the plasma was composed of two main spots, CS-023 and R-131624. R-131624 is a pharmacologically inactive metabolite with an open β-lactam ring (Fig. 1). CS-023 was the dominant radioactive spot in the plasma up to 0.5 h after administration. R-131624 was detectable in plasma at 5 min after administration. This metabolite reached almost the same concentration as CS-023 at around 0.5 h postdose and thereafter exceeded that of CS-023. The mean AUC0-∞ of the radioactivity ± the standard deviation (SD) was estimated to be 26.8 ± 4.8 μg · h/ml (n = 4), and 50% and 40% of the value consisted of CS-023 and R-131624, respectively.

(ii) Monkeys.

Plasma concentration-time profiles of total radioactivity, CS-023, R-131624, and an unknown metabolite are shown in Fig. 3B. Typical TLC autoradioluminograms of monkey plasma are shown in Fig. 5.

FIG. 5.

Typical TLC autoradioluminograms of radioactivity in plasma, urine, and feces after a single intravenous administration of [14C]CS-023 to monkeys at a dose of 10 mg/kg.

The radioactivity in plasma was composed of three spots, CS-023, R-131624, and the unknown metabolite. CS-023 was the dominant radioactive spot in monkey plasma at all of the time points investigated, unlike in rat plasma. Both R-131624 and the unknown metabolite were detected in the plasma even at 5 min after administration, and up to 0.5 h postdose the concentrations of the unknown metabolite were slightly higher than those of R-131624. R-131624 and the unknown metabolite accounted for not more than 25% of the plasma radioactivity, with the radioactivity due to CS-023 being more than 75%. The mean AUC0-∞ of the radioactivity ± the SD was estimated to be 87.4 ± 17.1 μg · h/ml (n = 3), and 55%, 5%, and 3% of the value consisted of CS-023, R-131624, and the unknown metabolite, respectively.

Mass balance. (i) Rats.

The time courses of the urinary and fecal excretion ratios of [14C]CS-023 radioactivity are shown in Fig. 6A. Typical TLC autoradioluminograms of rat urine, feces, and bile are shown in Fig. 4.

FIG. 6.

Time courses of cumulative excretion ratios of radioactivity after a single intravenous administration of [14C]CS-023 to rats (A) and monkeys (B) at a dose of 10 mg/kg. Each data point represents the mean ± the SD of four rats or three monkeys, respectively.

Most of the radioactivity administered was excreted in the urine during the first 24-h period. The urinary and fecal excretion ratios of the radioactivity over a 7-day period were 87.1% and 12.5%, respectively, and 99.6% in total. In the bile duct-cannulated rats, the biliary excretion of radioactivity was found to be almost negligible, being only 0.54% of the dose during the first 48 h after dosing.

The radioactivity excreted in the urine and feces over a period of 24 h postdose was composed of CS-023 and R-131624, which accounted for 29.6 and 31.4%, respectively, of the dose in urine and for 3.1 and 1.3%, respectively, of the dose in feces.

(ii) Monkeys.

The time courses of the urinary and fecal excretion ratios of [14C]CS-023 radioactivity are shown in Fig. 6B. Typical TLC autoradioluminograms of monkey urine and feces are shown in Fig. 5.

The excretion profiles of [14C]CS-023 radioactivity in the urine and feces of monkeys were similar to those in rats. The urinary and fecal radioactivity excretion ratios over a 7-day period were 88.0% and 7.5%, respectively, and 95.4% in total.

CS-023 and R-131624 were mainly detected in the urine and feces. The excretion ratios of CS-023 and R-131624 were 51.2 and 18.5%, respectively, of the dose in the urine and 0.7 and 0.7%, respectively, of the dose in the feces over the 24-h postdose period. The unknown metabolite in the plasma was also detected in the urine and feces: 2.7% of the dose in urine and 0.3% of the dose in feces.

Plasma concentration-time profiles in rats, dogs, and monkeys.

Mean plasma concentration-time profiles of CS-023 following intravenous administration of nonradiolabeled CS-023 to rats, dogs, and monkeys are shown in Fig. 7. The pharmacokinetic parameters of CS-023 in each animal species are summarized in Table 1.

FIG. 7.

Plasma concentration-time profiles of CS-023 after a single intravenous administration of CS-023 to rats (A), dogs (B), and monkeys (C). The limit of quantitation was 1 μg/ml for rat and dog plasma and 2 μg/ml for monkey plasma. Each data point represents the mean ± the SD of three animals.

TABLE 1.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of CS-023 in rats, dogs, and monkeys after intravenous administrationa

| Species and dose (mg/kg) | t1/2 (h) | AUC0-∞ (μg·h/ml) | CL (ml/min/kg) | Vss (ml/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rat | ||||

| 10 | 0.16 (0.05) | 10.2 (2.3) | 16.9 (3.5) | 199 (11) |

| 25 | 0.19 (0.02) | 28.4 (5.8) | 15.1 (3.4) | 218 (29) |

| 50 | 0.20 (0.02) | 55.0 (4.4) | 15.2 (1.2) | 220 (18) |

| Dog | ||||

| 5 | 0.75 (0.06) | 18.8 (1.0) | 4.44 (0.23)b | 269 (23) |

| 10 | 0.75 (0.10) | 39.9 (2.4) | 4.19 (0.26) | 259 (44) |

| 25 | 0.88 (0.04) | 128.6 (13.4) | 3.26 (0.34)b | 228 (33) |

| Monkey | ||||

| 5 | 1.32 (0.04) | 48.6 (9.4) | 1.76 (0.37) | 176 (33) |

| 10 | 1.39 (0.16) | 103.9 (11.3) | 1.62 (0.16) | 172 (21) |

| 25 | 1.44 (0.16) | 244.1 (35.8) | 1.73 (0.24) | 184 (9) |

Each value represents the mean of three animals with the corresponding SD in parentheses.

Significant difference (P < 0.05) between the 5- and 25-mg/kg doses.

In the dose ranges tested, the plasma concentrations of CS-023 declined with t1/2 values of 0.16 to 0.20 h for rats, 0.75 to 0.88 h for dogs, and 1.32 to 1.44 h for monkeys. Rats showed the highest CL values, followed by dogs and monkeys. The CLR values in rats and monkeys were 5.00 and 0.829 ml/min/kg, respectively.

In all of the animal species tested, the AUC0-∞ increased almost in proportion to the dose administered. The CL, Vss, and t1/2 values did not show significant differences between the dose levels examined in each animal, except for CL values in dogs. Although a significant but small difference was observed only in the CL values between the dose levels in dogs, these findings demonstrate the linear pharmacokinetic characteristics of CS-023 in a dose range of 10 to 50 mg/kg in rats and 5 to 25 mg/kg in dogs and monkeys.

Serum protein binding in vitro.

Serum protein-binding ratios of CS-023 at 20 μg/ml and 100 μg/ml (mean ± SD, n = 4) were 5.0% ± 3.1% and 5.9% ± 3.1%, respectively, in rats; 9.0% ± 3.3% and 5.4% ± 2.6%, respectively, in dogs; and 15.6% ± 3.8% and 15.1% ± 7.7%, respectively, in monkeys.

DISCUSSION

To examine the fate of CS-023 in experimental animals, the distribution, metabolism, and excretion of radioactivity were investigated in rats and monkeys after a single intravenous administration of [14C]CS-023. In addition, the plasma concentration-time profiles were measured in rats, dogs, and monkeys and the pharmacokinetic parameters were obtained.

Radioactivity was detected throughout the body, except for the central nervous system (the brain and spinal cord) and testes at 15 min after administration of [14C]CS-023 to rats (Fig. 2). The Vss values of CS-023 in rats, as well as in dogs and monkeys, were around 200 ml/kg (Table 1), suggesting that CS-023 is predominantly distributed to the extracellular fluid in the body after intravenous administration (2). This limited distribution of CS-023 in the body would be a favorable property for an antimicrobial agent, since most infecting microorganisms reside in the extracellular space (14). Furthermore, the serum protein-binding ratios of CS-023 were relatively low in all of the species studied, 5% in rats, 9% in dogs, and 15% in monkeys. A low protein-binding ratio would also be a favorable property for CS-023, since the protein-unbound, free form of CS-023 in plasma is the pharmacologically active fraction, which achieves rapid equilibrium with the drug in the extravascular fluid. Humans also have a Vss value, 230 ml/kg, comparable to the extracellular fluid volume and a low protein-binding ratio, 9.5%, as well as rats, dogs, and monkeys (13).

Higher plasma concentrations of R-131624 were observed in rats compared with those in monkeys after intravenous administration of [14C]CS-023 (Fig. 3). This species difference can be reasonably explained by considering the tissue distribution of the enzyme responsible for the metabolism of CS-023 to R-131624. Carbapenems including CS-023 are known to be hydrolyzed at the β-lactam ring by mammalian DHP-I (3, 6, 8), even though they are resistant to β-lactamase of bacterial origin. DHP-I has been reported to be highly expressed in the lungs of rats, whereas little is expressed in the lungs of monkeys (16). Therefore, the rapid appearance of R-131624 in rat plasma is considered to be attributable to the hydrolysis of CS-023 by DHP-I in the lungs. The higher CL value in rats than in monkeys would be due to the existence of CS-023 metabolism in the lungs (Table 1). On the other hand, in humans, similar to its expression in monkeys, DHP-I is reported to be expressed little in the lungs (16). In fact, in clinical pharmacokinetic studies, a low plasma concentration of R-131624 was observed (about 1/10 of the AUC value) after administration of CS-023 to humans (unpublished data).

Urinary excretion of R-131624 in monkeys reached 18.5% of the dose and was two-thirds of that in rats, although the concentrations of this metabolite in monkey plasma were almost negligible, unlike in rat plasma (Fig. 3). It has been indicated that DHP-I expressed on the luminal side of the renal tubule is involved in the metabolism of imipenem (5) and meropenem (1) in humans. In addition, DHP-I is expressed in the kidneys of monkeys, as well as in human kidneys (16). Therefore, it is likely that the R-131624 recovered in monkey urine was partly generated on the luminal side of the renal tubule after glomerular filtration.

The CLR of CS-023 in rats, 5.00 ml/min/kg, was almost comparable to the glomerular filtration rate (GFR), 5.24 ml/min/kg (2), suggesting that net renal tubular secretion or reabsorption is negligible in the renal excretion of the drug. On the other hand, the CLR in monkeys, 0.829 ml/min/kg, was less than half of the GFR, 2.08 ml/min/kg (2), suggesting that net renal tubular reabsorption is involved in the renal excretion of the drug. The reasons for this species difference remain to be elucidated. In humans, however, the CLR is reported to be closely comparable to the GFR (13). There seem to be differences in the renal excretion mechanism between monkeys and other animals, including humans.

The findings in the present study indicated that CS-023 is extensively distributed in tissues with low serum protein binding and is eliminated by both renal excretion and metabolism in rats and monkeys. The metabolism of CS-023 in monkeys rather than that in rats would be helpful in understanding that in humans, although the renal excretion mechanism in rats rather than that in monkeys is likely to be similar to that in humans.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 30 October 2006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Burman, L. A., I. Nilsson-Ehle, M. Hutchison, S. J. Haworth, and S. R. Norrby. 1991. Pharmacokinetics of meropenem and its metabolite ICI 213,689 in healthy subjects with known renal metabolism of imipenem. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 27:219-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davies, B., and T. Morris. 1993. Physiological parameters in laboratory animals and humans. Pharm. Res. 10:1093-1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fukasawa, M., Y. Sumita, E. T. Harabe, T. Tanio, H. Nouda, T. Kohzuki, T. Okuda, H. Matsumura, and M. Sunagawa. 1992. Stability of meropenem and effect of 1 beta-methyl substitution on its stability in the presence of renal dehydropeptidase I. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 36:1577-1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goa, K. L., and S. Noble. 2003. Panipenem/betamipron. Drugs 63:913-925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kahan, F. M., H. Kropp, J. G. Sundelof, and J. Birnbaum. 1983. Thienamycin: development of imipenem-cilastatin. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 12(Suppl. D):1-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kawamoto, I., Y. Shimoji, O. Kanno, K. Kojima, K. Ishikawa, E. Matsuyama, Y. Ashida, T. Shibayama, T. Fukuoka, and S. Ohya. 2003. Synthesis and structure-activity relationships of novel parenteral carbapenems, CS-023 (R-115685) and related compounds containing an amidine moiety. J. Antibiot. 56:565-579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koga, T., T. Abe, H. Inoue, T. Takenouchi, A. Kitayama, T. Yoshida, N. Masuda, C. Sugihara, M. Kakuta, M. Nakagawa, T. Shibayama, Y. Matsushita, T. Hirota, S. Ohya, Y. Utsui, T. Fukuoka, and S. Kuwahara. 2005. In vitro and in vivo antibacterial activities of CS-023 (RO4908463), a novel parenteral carbapenem. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:3239-3250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kropp, H., J. G. Sundelof, R. Hajdu, and F. M. Kahan. 1982. Metabolism of thienamycin and related carbapenem antibiotics by the renal dipeptidase, dehydropeptidase-I. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 22:62-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Masuda, N., S. Ohya, T. Takenouchi, M. Kakuta, C. Ishii, E. Sakagawa, T. Abe, and S. Kuwahara. 2000. R-115685, a novel parenteral carbapenem: mode of action and resistance mechanisms, abstr. F-1231. In Abstracts of the 40th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 10.Nix, D. E., A. K. Majumdar, and M. J. DiNubile. 2004. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of ertapenem: an overview for clinicians. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 53:ii23-ii28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pacifici, G. M., and A. Viani. 1992. Methods of determining plasma and tissue binding of drugs. Pharmacokinetics consequences. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 23:449-468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perry, C. M., and T. Ibbotson. 2002. Biapenem. Drugs 62:2221-2234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rennecke, J. T., T. Hirota, T. Shibayama, Y. Matsushita, S. Kuwahara, K. Puchler, A. Ruhland, and B. Drewelow. 2002. Safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics (PK) of CS-023, a new parenteral carbapenem, in healthy male volunteers, abstr. F-327. In Abstracts of the 42nd Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. American Society for Microbiology. Washington, D.C.

- 14.Shentag, J. J. 1990. The significance of the relationship between tissue:serum ratios, tissue concentrations and the location of microorganisms. Res. Clin. Forums 12:23-27. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sundelof, J. G., R. Hajdu, C. J. Gill, R. Thompson, H. Rosen, and H. Kropp. 1997. Pharmacokinetics of L-749,345, a long-acting carbapenem antibiotic, in primates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:1743-1748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takahagi, H., T. Hirota, Y. Matsushita, S. Muramatsu, M. Tanaka, and E. Matsuo. 1991. In vitro dehydropeptidase-I activity and its hydrolytic activity of panipenem in several tissues in animal species and their influence on the disposition of panipenem in vivo. Chemotherapy (Tokyo) 39(Suppl. 3):236-241. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomson, K. S., and E. S. Moland. 2004. CS-023 (R-115685), a novel carbapenem with enhanced in vitro activity against oxacillin-resistant staphylococci and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 54:557-562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wiseman, L. R., A. J. Wagstaff, R. N. Brogden, and H. M. Bryson. 1995. Meropenem. A review of its antibacterial activity, pharmacokinetic properties and clinical efficacy. Drugs 50:73-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamamoto, C., T. Takahashi, K. Kinoshita, and T. Fujita. 1982. The metabolic fate of 4-amino-2-(4-butanoylhexahydro-1H-1,4-diazepin-1-yl)-6,7- dimethoxy-quinazoline HCl. Xenobiotica 12:549-559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]