Abstract

A carbapenem-resistant isolate of Klebsiella pneumoniae producing class A carbapenemase KPC-2 was identified in Zhejiang, China. The KPC-2 gene was located on an approximately 60-kb plasmid in a genetic environment partially different from that of blaKPC-2 in the isolates from the United States and Colombia.

Resistance to carbapenems in Klebsiella pneumoniae remains infrequent and is mainly caused by carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamases, including IMP-, VIM-, and KPC-type enzymes and OXA-48 (5, 9, 10). The impact of KPC-type carbapenemase is on the increase. The initial report of KPC-1 β-lactamases involved a strain of K. pneumoniae recovered in North Carolina (16). Soon afterward, KPC-type β-lactamases were reported in the northeastern United States among K. pneumoniae (1, 2, 11, 15), Klebsiella oxytoca (17), Salmonella enterica (7), and Enterobacter sp. (4) isolates. Recently, K. pneumoniae and Escherichia coli isolates producing KPC-2 were reported in Medellin, Colombia (12), upstate New York (6), and Israel (8).

In the present study we report on the detection of a KPC-2-producing K. pneumoniae isolate from a university hospital in Zhejiang, China.

The carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae ZR01 strain was isolated from the sputum of a 75-year-old patient hospitalized in the intensive care unit on 20 November 2004. The patient suffered from brain stem infarction, hypertensive disease, and coronary heart disease and had been admitted to the hospital on 19 January 2004. The patient died on 7 December 2004 of respiratory failure secondary to lower respiratory tract infection caused by the organism. During hospitalization, imipenem was repeatedly administered (total dosage of imipenem received, 80 g).

Identification of the isolate was determined by API 20E (bioMerieux). Susceptibility tests were performed by the agar dilution method according to guidelines of CLSI (formerly NCCLS) (3). K. pneumoniae ZR01 was resistant to all tested antimicrobial agents except polymyxin B and colistin (Table 1 ). MICs of imipenem and meropenem were slightly reduced in the presence of clavulanic acid.

TABLE 1.

Antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of K. pneumoniae ZR01, E. coli(pYW1), and E. coli(pYW2)

| Isolate, vector, or transformant | MIC (μg/ml) of indicated antimicrobial agent:

|

|||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imip- enem | Imipenem-clavulanic acida | Merop- enem | Meropenem-clavulanic acida | Ertap- enem | Cefepime | Cefta- zidime | Cefotaxime | Ceftriaxone | Aztreonam | Cefoperazone-sulbactam | Piperacillin-tazobactam | Ciproflox- acin | Amikacin | Genta- micin | Rifam- pin | Colis- tin | Poly- myxin B | |

| K. pneumoniae ZR01 | >32 | 16 | >32 | 16 | >256 | >256 | >256 | >256 | >256 | >256 | >256 | >256 | >32 | >256 | >256 | 16 | 0.5 | 2 |

| E. coli(pYW1) (trans- formant) | 4 | 0.5 | 4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 32 | 16 | 128 | 0.012 | 1 | 0.125 | 16 | 0.5 | 1 |

| E. coli DH5α | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.008 | 0.032 | 0.25 | 0.094 | 0.094 | 0.125 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.012 | 1 | 0.125 | 16 | 0.5 | 1 |

| E. coli (pYW2) | 8 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 16 | 32 | 32 | 64 | 64 | 64 | >256 | 0.012 | 1 | 0.125 | 16 | 0.5 | 1 |

| E.coli (pGEM-T Easy) (vector) | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.012 | 0.125 | 0.5 | 0.094 | 0.094 | 0.125 | 6 | 16 | 0.012 | 1 | 0.125 | 16 | 0.5 | 1 |

Clavulanic acid was tested at a fixed concentration of 4 μg/ml.

Attempts to transfer imipenem resistance from K. pneumoniae ZR01 to the rifampin-resistant strain of E. coli 600 by a mixed-broth mating procedure (14) failed. Mueller-Hinton agar (MHA) containing 1 μg/ml imipenem and 250 μg/ml rifampin was used to select the transconjugants. Plasmids of K. pneumoniae ZR01 were extracted by using the QIAGEN Plasmid Midi kit (QIAGEN) and were transformed into competent E. coli DH5α. Transformants were selected on MHA containing 1 μg/ml imipenem. The transformant, E. coli(pYW1), harbored a single plasmid with a size of approximately 60 kb, while K. pneumoniae ZR01 contained three plasmids with sizes of approximately 100 kb, 60 kb, and 2 kb (data not shown). MICs of imipenem and meropenem for the E. coli transformant were lower than those for K. pneumoniae ZR01 (Table 1). It is possible that alterations in porin expression affect the MICs of these antibiotics in K. pneumoniae strains (15, 16).

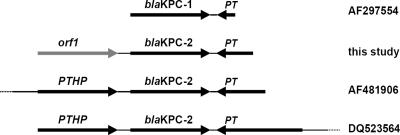

The plasmid from E. coli(pYW1) was digested by NheI, and fragments were cloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector. An imipenem-nonsusceptible E. coli DH5α derivative [named E. coli(pYW2)], containing a 2.1-kb cloned fragment, was obtained. Nucleotide sequencing of the cloned fragment revealed the presence of two open reading frames. The nucleotide sequence of orf2 (879 bp) had 100% identity with blaKPC-2 (GenBank accession number AY210886). Upstream of blaKPC-2 was orf1 (885 bp), encoding a putative 259-amino-acid protein showing significant similarity (55 to 60%) to several (putative) transposase or integrase proteins (GenBank accession numbers YP_355552.1, ZP_01384016.1, YP_583434.1, AAR98533.1, and NP_682719.1). PCR mapping and sequencing experiments using primers designed with the sequence designated by GenBank number AF481906 (KPC-I, 5′-CGGAACCTGCGGAGTGTATG-3′, starting at bp 4265; and KPC-J, 5′-CAGCAGTTCAGGCCAACACC-3′, starting at bp 5067) and the plasmid pYW1 as templates revealed that the sequence downstream of blaKPC-2 in pYW1 was identical to that present downstream of the blaKPC-2 genes in isolates from the United States and Colombia (GenBank accession numbers AF481906 and DQ523564). Interestingly, this structure was also found downstream of blaKPC-1 (GenBank accession number AF297554) (Fig. 1), suggesting that the putative transposase gene present downstream of KPC-type genes might be involved in the mobility of KPC genes. No discernible epidemiological linkage could be established between K. pneumoniae ZR01 and KPC-2-producing isolates from the United States, according to the patient record.

FIG. 1.

Comparison of the blaKPC genetic contexts in different plasmids. In this study, downstream of blaKPC-2 a putative transposase gene (PT), which was identical to that detected downstream of blaKPC genes in plasmids from the United States (GenBank accession numbers AF297554 and AF481906) and Colombia (GenBank accession number DQ523564), was detected. Upstream of blaKPC-2 an open reading frame (orf1), which was different from the putative transposase helper protein gene (PTHP) found upstream of blaKPC genes in other KPC-2-encoding plasmids, was detected.

Crude cell lysates were prepared by ultrasonication from K. pneumoniae ZR01, E. coli(pYW1), and E. coli(pYW2), as described previously (14). β-Lactamases were characterized by isoelectric focusing with the PhastSystem (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) according to established methods. The results showed that K. pneumoniae ZR01 had three β-lactamase bands of pI 8.2, 6.7, and 5.4 (data not shown). The presence of TEM-1, SHV-12, and KPC-2 genes in K. pneumoniae ZR01 was confirmed by PCR and sequencing. E. coli(pYW1) showed a single β-lactamase band of pI 6.7, in agreement with the production of KPC-2 (data not shown). This indicated that plasmid pYW1 carried only the KPC-2 β-lactamase gene, unlike the KPC-2-encoding plasmid from S. enterica, which also carried a blaTEM-1 gene (7), and the KPC-2-encoding plasmid from K. oxytoca, which also carried a blaTEM-1 and a blaSHV-46 gene (17). E. coli(pYW2) showed two bands of pI 6.7 and 5.4 (the latter corresponding to TEM-1 from the pGEM-T Easy vector).

In China, carbapenems were widely used to treat serious gram-negative nosocomial infections. The presence of carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii is increasing. Among 10 university hospitals in China, the isolation rates of carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa and A. baumannii were 24% and 18%, respectively (13). A strain of Enterobacter cloacae producing class A carbapenemase IMI-2 (18) was isolated in the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University. Though this isolate's occurrence was sporadic, KPC-producing strains are worrisome in the clinic, due to the potential for epidemic spread, as observed in the northeastern area of the United States (1, 2, 6, 15). In order to avoid the epidemic of strains producing KPCs, strict resistance surveillance and drug administration should be emphasized in this area.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of the cloning fragment obtained from K. pneumoniae ZR01 was assigned GenBank accession number DQ897687.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a grant from the Program for New Century Excellent Talents in University (NCET-04-0552).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 4 December 2006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bradford, P. A., S. Bratu, C. Urban, M. Visalli, N. Mariano, D. Landman, J. J. Rahal, S. Brooks, S. Cebular, and J. Quale. 2004. Emergence of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella species possessing the class A carbapenem-hydrolyzing KPC-2 and inhibitor-resistant TEM-30 beta-lactamases in New York City. Clin. Infect. Dis. 39:55-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bratu, S., M. Mooty, S. Nichani, D. Landman, C. Gullans, B. Pettinato, U. Karumudi, P. Tolaney, and J. Quale. 2005. Emergence of KPC-possessing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Brooklyn, New York: epidemiology and recommendations for detection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:3018-3020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2006. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically, 7th ed. Approved standard M7-A6. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, Pa.

- 4.Hossain, A., M. J. Ferraro, R. M. Pino, R. B. Dew III, E. S. Moland, T. J. Lockhart, K. S. Thomson, R. V. Goering, and N. D. Hanson. 2004. Plasmid-mediated carbapenem-hydrolyzing enzyme KPC-2 in an Enterobacter sp. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:4438-4440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ikonomidis, A., D. Tokatlidou, I. Kristo, D. Sofianou, A. Tsakris, P. Mantzana, S. Pournaras, and A. N. Maniatis. 2005. Outbreaks in distinct regions due to a single Klebsiella pneumoniae clone carrying a blaVIM-1 metallo-β-lactamase gene. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:5344-5347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lomaestro, B. M., E. H. Tobin, W. Shang, and T. Gootz. 2006. The spread of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae to upstate New York. Clin. Infect. Dis. 43:e26-e28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miriagou, V., L. S. Tzouvelekis, S. Rossiter, E. Tzelepi, F. J. Angulo, and J. M. Whichard. 2003. Imipenem resistance in a Salmonella clinical strain due to plasmid-mediated class A carbapenemase KPC-2. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:1297-1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Navon-Venezia, S., I. Chmelnitsky, A. Leavitt, M. J. Schwaber, D. Schwartz, and Y. Carmeli. 2006. Plasmid-mediated imipenem-hydrolyzing enzyme KPC-2 among multiple carbapenem-resistant Escherichia coli clones in Israel. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:3098-3101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nordmann, P., and L. Poirel. 2002. Emerging carbapenemases in gram-negative aerobes. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 8:321-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poirel, L., C. Héritier, V. Tolün, and P. Nordmann. 2004. Emergence of oxacillinase-mediated resistance to imipenem in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:15-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith Moland, E., N. D. Hanson, V. L. Herrera, J. A. Black, T. J. Lockhart, A. Hossain, J. A. Johnson, R. V. Goering, and K. S. Thomson. 2003. Plasmid-mediated, carbapenem-hydrolysing beta-lactamase, KPC-2, in Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 51:711-714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Villegas, M. V., K. Lolans, A. Correa, C. J. Suarez, J. A. Lopez, M. Vallejo, J. P. Quinn, and Colombian Nosocomial Resistance Study Group. 2006. First detection of the plasmid-mediated class A carbapenemase KPC-2 in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae from South America. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:2880-2882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang, H., M. Chen, Y. Ni, D. Chen, Z. Sun, Y. Chen, W. Zhao, X. Zou, Y. Yu, Z. Hu, X. Huang, Y. Xu, X. Xie, Y. Chu, Q. Wang, Y. Mei, B. Tian, P. Zhang, Q. Kong, X. Yu, and Y. Pan. 2005. Antimicrobial resistance analysis among nosocomial gram negative bacilli from 10 teaching hospitals in China. Chin. J. Lab. Med. 28:1295-1303. (In Chinese.) [Google Scholar]

- 14.We, Z. Q., Y. G. Chen, Y. S. Yu, W. X. Lu, and L. J. Li. 2005. Nosocomial spread of multi-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae containing a plasmid encoding multiple β-lactamases. J. Med. Microb. 54:885-888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woodford, N., P. M. Tierno, Jr., K. Young, L. Tysall, M. F. Palepou, E. Ward, R. E. Painter, D. F. Suber, D. Shungu, L. L. Silver, K. Inglima, J. Kornblum, and D. M. Livermore. 2004. Outbreak of Klebsiella pneumoniae producing a new carbapenem-hydrolyzing class A beta-lactamase, KPC-3, in a New York medical center. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:4793-4799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yigit, H., A. M. Queenan, G. J. Anderson, A. Domenech-Sanchez, J. W. Biddle, C. D. Steward, S. Alberti, K. Bush, and F. C. Tenover. 2001. Novel carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamase, KPC-1, from a carbapenem-resistant strain of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1151-1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yigit, H., A. M. Queenan, J. K. Rasheed, J. W. Biddle, A. Domenech-Sanchez, S. Alberti, K. Bush, and F. C. Tenover. 2003. Carbapenem-resistant strain of Klebsiella oxytoca harboring carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamase KPC-2. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:3881-3889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu, Y. S., X. X. Du, Z. H. Zhou, Y. G. Chen, and L. J. Li. 2006. First isolation of blaIMI-2 in an Enterobacter cloacae clinical isolate from China. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:1610-1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]