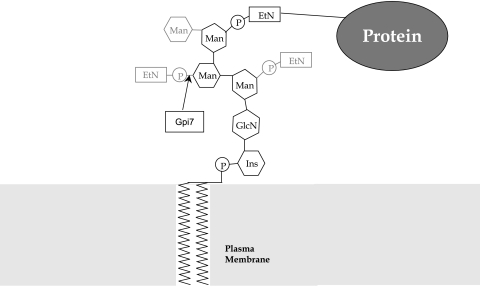

There are two types of membrane proteins: the integral membrane proteins and the lipid-anchored proteins. Integral membrane proteins contain one or several transmembrane domains that allow for the formation of hydrophobic α-helices, which ultimately embed the protein in a lipid bilayer. We count four types of lipid-anchored proteins divided into two groups: one group generally links the proteins to the internal side of the plasma membrane and the other generally links them to the outside. In the first group are found the amide-linked myristoyl anchors (calcineurin B) (6), the (thio)ester-linked fatty acyl anchors, and the thioether-linked prenyl anchors (G protein alpha subunits) (13). The second group is composed only of the proteins that contain a C-terminal signal sequence that allows for linkage to a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor. The anchor of the GPI-anchored proteins (GpiPs) can be removed by the action of specific phospholipases (24), converting the protein into a water-soluble form. GpiPs are thought to associate with lipid rafts, specialized regions of the membrane containing elevated levels of cholesterol and sphingolipids, common to human cells, for example (48). Proteins destined to be GPI anchored share conserved features: an N-terminal signal sequence for localization to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), a C-terminal hydrophobic domain (9 to 24 residues) for transient attachment to the ER membrane, and the so-called ω site, where the protein is cleaved to be ligated to the GPI anchor (57). The ω site is localized 9 to 10 amino acids before the C-terminal hydrophobic domain, and its amino acid environment determines whether the protein has a high probability to be GPI anchored. Amino acids at positions ω-1 to ω-11 form a linker region usually with no charge and no secondary structure (α-helix or β-sheet). The ω site region is composed of small amino acids to fit the transamidase protease catalytic pocket, and finally, the spacer region (ω+3 to ω+9) is comparable to the linker, having no charge and being flexible (16). Shortly after protein synthesis in the ER, the preformed GPI anchor replaces the C-terminal transmembrane region. The core GPI anchor consists of a lipid group (serving as the membrane anchor), a myoinositol group, an N-acetylglucosamine group, three mannose groups, and a phosphoethanolamine group, which ultimately connects the GPI anchor to the protein via an amide linkage (58) (Fig. 1). The addition of mannose groups and the positioning of side chains like phosphoethanolamine on the GPI anchor contributes to the variety of GPI anchors identified so far (Fig. 1). We will not discuss GPI anchor biosynthesis in this review since we have decided to focus the review on the proteins only, but it is important to note that the GPI anchors are essential for viability in yeast since any deletion of proteins key in GPI biogenesis is lethal (15, 37, 58).

FIG. 1.

GPI anchor structure. The core structure found in any eukaryotic cell is represented in black. The additional gray groups illustrate the side chains added to the GPI anchor in S. cerevisiae (side chains are specific to each organism). Gpi7 is a protein involved in the addition of the ethanolamine phosphate side chain to the second mannose group in S. cerevisiae and C. albicans. EtN, ethanolamine; Ins, inositol; P, phosphore.

GPI anchoring is encountered in every eukaryotic cell, including unicellular yeast cells, cells of several parasites, and the highly specialized mammalian cells (7, 17, 38). Nevertheless, this wide occurrence does not dictate specific functions, as many types of proteins are GPI anchored (glucosidase, alpha amylase, aspartyl protease, superoxide dismutase, and phospholipase, etc.) and many GpiPs have unknown functions (2, 11, 18, 39). From the human perspective, GpiPs have been under investigation for two specific reasons: (i) a rare defect in the biosynthesis of the GPI anchor itself triggers a disease called paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria affecting the protection of erythrocytes against complement factors (28), and (ii) PrP* is a GPI-anchored protein derived from the normal PrP(c) that causes various fatal neurodegenerative diseases, such as the well-known Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease (36). In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, of the characterized GpiPs, most are involved in cell wall compound biosynthesis, flocculation, protease activity, sporulation, and mating (9).

CANDIDA ALBICANS POSSESSES 115 PUTATIVE GPI-ANCHORED PROTEINS

The availability of more and more eukaryotic genome sequences has given us the resources to do large-scale comparative-genomics studies of GpiPs. The only way to anticipate the addition of a GPI anchor is to look for the three characteristics described above. However, none of these characteristics are strictly defined, thus confounding our interpretations. In the last 4 years, several studies have increased our understanding of the numbers and functions of the GpiPs. In terms of the human genome, no large-scale analysis of GpiPs has been published yet, but in the B. Eisenhaber laboratory, a preliminary survey of potentially GPI-modified proteins in Homo sapiens sapiens was done in 2004 (http://mendel.imp.ac.at/gpi/Hs/hs.html). Lower eukaryotes, such as Arabidopsis thaliana (5) and Caenorhabditis elegans (14), and microorganisms, such as Aspergillus nidulans, C. albicans, Candida glabrata, Neurospora crassa, S. cerevisiae, and Schizosaccharomyces pombe (9, 12, 14, 16, 55, 61), however, have been subjected to a more thorough analysis. It is notable that S. cerevisiae and Schizosaccharomyces pombe seem to possess a smaller number of GpiPs than C. albicans.

Four different lists of C. albicans GpiPs are published in the literature (12, 16, 21, 55). In this review, we will not include the results of Paula Sundstrom's analysis since her work was done using assembly 6, an incomplete genome sequence. In an attempt to simplify our analysis, we have made a comprehensive list of putative GpiPs by combining the three data sets identified from assembly 19 (12, 16, 21). The three different teams presenting lists of C. albicans GpiPs identified different numbers of putative GpiPs (102, 104, and 169), but a careful analysis of each data set allowed us to refine our list (Table 1). Other than the differences in the algorithms used to define GpiPs, the main reasons for the differences among the data sets were the presence in the data sets of open reading frames (ORFs) that have since been deleted and the presence in the data sets of two alleles coding for the same GpiP. The recent publication online of release 20, a complete and curated haploid genome sequence for C. albicans (http://candida.bri.nrc.ca/candida/index.cfm), has allowed for the creation of a robust base for further research on this group of proteins in C. albicans or for comparison with other organisms.

TABLE 1.

GPI-anchored proteins in C. albicansa

| Protein | Gene numberb

|

Identified homologue(s)c | % Identity/ % similarityd | Localizatione | Regulator(s)f | Virulence of deletion mutant | Predicted function | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| orf6 | orf19 | |||||||

| Proteins common to all 3 studies | ||||||||

| Als1 | 1115 | 5741 | ScSag1 | 26/43 | Biofilm formation, Rfg1, Ssk1, growth | Defective | Involved in cell-cell adhesion | |

| Als5 | 4915 | 5736 | ScSag1 | 27/45 | ND (no mutant described) | By homology, involved in cell-cell adhesion | ||

| Als6 | 8574 | 7414 | ScSag1 | 26/44 | ND (no mutant described) | By homology, involved in cell-cell adhesion | ||

| Cht2 | 2344 | 3895 | ScCts1 | 43/55 | Caspofungin, yeast-form cells, Cyr1, Efg1, pH | ND (not tested) | By homology, chitinase | |

| Crh11 | 1231 | 2706 | ScCrh1 | 56/71 | CW (N) | Caspofungin | ND (no mutant described) | By homology, cell wall glycosidase of the cell wall |

| Csa1 | 8439 | 7114 | None | CW (V) | Morphogenesis switch, Rim101, Efg1, Cph1 | ND (not tested) | Surface antigen on elongating hyphae and buds | |

| Dfg5 | 7480 | 2075 | ScDcw1 | 50/70 | Mb (K, K) | Caspofungin, morphogenesis switch | ND (not tested) | Unknown |

| Ecm331 | 3969 | 4255 | ScEcm33 | 33/52 | CW (N) | Caspofungin, Plc1, Rim101, Hog1, Cyr1, Ssn6 | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown |

| Exg2 | 6664 | 2952 | ScExg1 | 42/57 | Mb (K, K) | Cell wall regeneration | ND (no mutant described) | Putative exo-1,3-β-glucosidase by homology |

| Hwp1 | 4883 | 1321 | None | CW (I) | Morphogenesis, opaque and cell specific | Defective | Hyphal cell wall protein; covalently cross-linked to epithelial cells | |

| Hyr1 | 857 | 4975 | None | CW (N, I) | Morphogenesis switch, Rfg1, Efg1, Nrg1, Tup1, Cyr1 | ND (not tested) | Unknown | |

| Hyr3/Iff2 | 4725 | 575 | None | CW (I) | Iron | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | |

| Iff3 | 2179 | 4361 | None | CW (Y, I) | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | ||

| Iff4 | 8724 | 7472 | None | CW (I) | ND (not tested) | Unknown | ||

| Iff5 | 297 | 2879 | None | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | |||

| Iff6 | 2490 | 4072 | None | White-opaque switching | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | ||

| Hyr4/Iff7 | 8279 | 3279 | None | CW (N) | Rim101 | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | |

| Mid1 | 496 | 3212 | ScMid1 | 36/55 | Mb (K, K) | ND (no mutant described) | By homology, involved in Ca2+ influx during mating | |

| Pga1 | 8973 | 7625 | ScKre1 | 33/57 | CW (V) | Cell wall regeneration | ND (no mutant described) | By homology, cell wall glycoprotein involved in β-glucan assembly |

| Pga2/Sod4 | 7493 | 2062 | D. hansenii protein | 41/61 | White-opaque switching, caspofungin | ND (no mutant described) | Superoxide dismutase domain | |

| Pga3/Sod5 | 7495 | 2060 | D. hansenii protein | 41/58 | Neutrophil contact, morphogenesis, caspofungin | Defective | Superoxide dismutase domain | |

| Pga4/Gas1 | 7448 | 4035 | D. hansenii protein | 55/73 | Mb (K, K) | ND (no mutant described) | By homology, β-1,3-glucanosyltransferase | |

| Pga6/Flo9 | 4590 | 4765 | ScFlo9 | 28/45 | Iron, Als2 | ND (no mutant described) | Flocculin | |

| Pga10/Rbt51 or Rbt8 | 6914 | 5674 | D. hansenii protein | 46/58 | Ketoconazole, morphogenesis, Rim101 | ND (not tested) | Iron uptake using hemoglobulin | |

| Pga11 | 8957 | 7609 | None | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | |||

| Pga13 | 7834 | 6420 | None | CW (I) | Cell wall regeneration, caspofungin, Tsa1, Nrg1, Tup1, Cyr1 | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | |

| Pga14 | 8217 | 968 | ScYnl190w | 46/62 | Mb (K, R) | Cell wall regeneration, Ssn6 | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown |

| Pga15 | 4387 | 2878 | None | Mb (K) | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | ||

| Pga17 | 7284 | 893 | None | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | |||

| Pga18 | 4292 | 301 | None | CW (V) | Nrg1, Tup1 | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | |

| Pga20/Rbr1 | 450 | 535 | None | Mb (K) | Rim101, Nrg1 | ND (not tested) | Unknown | |

| Pga21/Rbr2 | 6744 | 532 | None | Rim101, white-opaque switching | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | ||

| Pga22 | 5468 | 3738 | None | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | |||

| Pga23 | 83 | 3740 | None | Rim101, Cyr1, Ssn6 | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | ||

| Pga24/YWP1 | 3288 | 3618 | D. hansenii protein | 34/48 | Mb (K, K) | Ssk1, Ssn6, Efg1, Efh1, phosphate | Normal | May promote dispersal of yeast forms of C. albicans |

| Pga26 | 4960 | 2475 | None | CW (V) | Iron, cell wall regeneration | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | |

| Pga28 | 311 | 5144 | None | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | |||

| Pga29/Rhd3 | 8294 | 5305 | None | CW (V) | Iron, morphogenesis switch | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | |

| Pga30 | 8292 | 5303 | None | CW (Y, V) | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | ||

| Pga33 | 7301 | 876 | None | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | |||

| Pga34 | 4494 | 2833 | None | Mb (K, K) | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | ||

| Pga36/Ihd1 | 6198 | 5760 | None | pH, morphogenesis switch, Nrg1, Rfg1, Tup1, Tsa1p, Tsa1Bp | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | ||

| Pga37 | 4053 | 3923 | None | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | |||

| Pga39 | 5495 | 6302 | None | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | |||

| Pga41 | 6116 | 2906 | None | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | |||

| Pga42 | 6115 | 2907 | None | Mb (K) | Overexpression of CDR1 and CDR2 or MDR1 | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | |

| Pga44 | 3113 | 1714 | None | CW (Y) | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | ||

| Pga45 | 1247 | 2451 | None | CW (V, I) | Caspofungin, Hog1, Ssn6 | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | |

| Pga46 | 2753 | 3638 | None | Mb (K) | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | ||

| Pga47/Eap1 | 5354 | 1401 | None | Efg1 | ND (no mutant described) | Involved in binding human epithelial cells | ||

| Pga48 | 5514 | 6321 | None | CW (V) | Iron | ND (no mutant described) | Weak homologue of ScSed1 and ScSpi1 | |

| Pga49 | 2824 | 4404 | None | Mb (R, R, R) | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | ||

| Pga50 | 3431 | 1824 | None | CW (I) and Mb (K) | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | ||

| Pga52 | 799 | 1911 | ScYjl171c | 52/68 | Mb (K, K) | Fluconazole | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown |

| Pga53 | 305 | 4651 | None | CW (I) and Mb (K) | Cyr1 | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | |

| Pga56 | N/D | 1105.2 | None | CW (N) | Morphogenesis switch, cell wall regeneration, Ssn6 | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | |

| Pga57 | 461 | 4689 | None | Mb (R) | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | ||

| Pga58 | 1698 | 4334 | None | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | |||

| Pga59 | 6585 | 2767 | None | Ssn6 | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | ||

| Pga60 | 4430 | 5588 | None | CW (N) | Morphogenesis switch | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | |

| Pga61 | 6196 | 5762 | None | CW (V) | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | ||

| Pga62 | 6587 | 2765 | None | Fluconazole, iron, cell wall regeneration, Cyr1, Ras1 | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | ||

| Phr1 | 7524 | 3829 | ScGas1 | 55/69 | Rim101 | Defective | By homology, β-1.3-glucanosyltransferase, required for cell wall assembly | |

| Phr2 | 1067 | 6081 | ScGas2 | 59/69 | Mb (K) | Rim101, fluconazole | Defective | By homology, beta-1.3- glucanosyltransferase, required for cell wall assembly |

| Plb3 | 6206 | 6594 | ScPlb1 | 53/67 | Mb (K) | ND (no mutant described) | By homology, phospholipase B | |

| Plb5 | 4037 | 5102 | ScPlb3 | 46/63 | Mb (K, K, K) | ND (no mutant described) | By homology, phospholipase B | |

| Rbt5 | 4505 | 5636 | None | CW (V) | Rfg1, Rim101, Sfu1, Hog1, Tup1, serum, iron, ketoconazole | Normal | Unknown | |

| Sap9 | 7314 | 6928 | ScYap3 | 33/50 | Mb (R) | Antifungal drugs, stationary phase, white phase | Defective | By homology, aspartyl proteinase |

| Ssr1 | 7956 | 7030 | ScCcw14/ScSsr1 | 57/67 | ND (not tested) | Required for cell wall integrity | ||

| Csf4/Utr2 | 1639 | 1671 | ScUtr2 | 42/58 | Cell wall regeneration, yeast form | Defective | By homology, 1,3-1,4-β-glucanase | |

| Pga7 | 4504 | 5635 | D. hansenii protein | 51/63 | Rim101, ketoconazole, planktonic growth | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | |

| Pga8/Hwp2 | 2933 | 3380 | None | CW (Y, I) | Efg1, Tup1 | ND (no mutant described) | By homology, extracellular α-1,4-glucan glucosidase | |

| Pga38 | 1332 | 2758 | None | 26/36 | Mb (K, K) | Cell wall regeneration | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown |

| Pga55 | 5166 | 207 | None | Morphogenesis, Nrg1, Tup1 | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | ||

| Rbt1 | 4889 | 1327 | None | CW(I) | Tup1, serum, morphogenesis, farnesol, alpha factor, Rim101 | Defective | Unknown | |

| Spr1 | 2395 | 2237 | ScSpr1 | 41/57 | CW (N) and Mb (K, K) | ND (not tested) | By homology, exo-1,3-β-glucanase precursor | |

| Proteins specific to de Groot et al. study | ||||||||

| Als9 | 2924 | 5742 | None | ND (no mutant described) | By homology, involved in cell-cell adhesion | |||

| Als2 | ND | 1097 | ScSag1 | 26/45 | Morphogenesis switch, ketoconazole, Iron, cell wall regeneration | Protein essential? | By homology, involved in cell-cell adhesion | |

| Als3 | 1614 | 1816 | ScSag1 | 27/44 | Morphogenetic switch, pH, Nrg1, Rfg1, Tup1 | Defective | By homology, involved in cell-cell adhesion | |

| Als4 | 3075 | 4555 | ScFlo1 | 22/39 | Vaginal contact | Normal | Involved in cell-cell adhesion | |

| Als7 | 8560 | 7400 | ScSag1 | 23/40 | CW (L, V) | Biofilm formation | ND (not tested) | By homology, involved in cell-cell adhesion |

| Cht1 | 8769 | 7517 | ScCts1 | 51/63 | Mb (K, R) | pH | ND (not tested) | By homology, chitinase |

| Ecm33 | N/D | 3010.1 | ScEcm33 | 29/43 | Mb (K, K) | Fluconazole induced; caspofungin repressed | Defective | Unknown |

| Iff8 | 4720 | 570 | None | CW (I) | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | ||

| Kre1 | 4542 | 4377 | ScKre1 | ND (sequence too short) | CW (N) and Mb (K) | Caspofungin | ND (no mutant described) | By homology, protein involved in 1,6-α-d-glucan biosynthesis |

| Pga5 | 3873 | 3693 | C. glabrata protein | 50/65 | Mb (K, K, K) | ND (no mutant described) | β-1,3-Glucanosyl transferase | |

| Pga9/Sod6 | 4753 | 2108 | D. hansenii protein | 47/64 | Planktonic growth | ND (no mutant described) | Superoxide dismutase domain | |

| Pga12 | 8945 | 7597 | D. hansenii protein | 44/59 | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | ||

| Pga16 | 901 | 848 | None | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | |||

| Pga19 | 5972 | 2033 | None | ND (not tested) | Unknown | |||

| Pga25 | 5529 | 6336 | None | Fluconazole | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | ||

| Pga27 | 5983 | 2044 | None | Mb (K, K, K) | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | ||

| Pga31 | 3932 | 5302 | D. hansenii protein | 38/59 | CW (V) and Mb (K, K) | White-opaque switch, cell wall regeneration | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown |

| Pga32 | 8847 | 6784 | None | Iron | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | ||

| Pga35/Fgr41 | 3757 | 4910 | D. hansenii protein | 30/40 | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | ||

| Pga40/Fgr23 | 555 | 1616 | None | CW (N) | Alpha factor | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | |

| Pga43 | 6112 | 2910 | None | Mb (K) | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | ||

| Pga51/Dcw1 | 1293 | 1989 | ScDcw1 | 55/70 | CW (L) | Cyr1 | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown |

| Pga54 | 4795 | 2685 | None | Hog1, Cyr1, Efg1, Ssn6 | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | ||

| Plb4.5 | N/D | 1442 | ScPlb1 | 42/58 | CW (V, V) and Mb (K, R) | Hog1, Ssn6 | ND (no mutant described) | By homology, phospholipase B |

| Proteins specific Eisenhaber et al. study | ||||||||

| Crh1 | 3505 | 3966 | D. hansenii protein | 38/53 | CW (I) | Nrg1, Tup1, Rim101, cell wall regeneration | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown |

| Sap10 | 7534 | 3839 | ScYap3 | 25/38 | Mb (K) | Iron | Defective | By homology, aspartyl proteinase |

| Iff9 | 353 | 465 | None | CW (Y, I) | Iron | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | |

| Unknown | 129 | 206 | None | CW (N, V) | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | ||

| Unknown | 66 | 4652 | None | Mb (K) | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | ||

| Unknown | 4704 | 4653 | None | Iron | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | ||

| Unknown | 4705 | 4654 | None | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | |||

| Unknown | 7864 | 6390 | None | Mb (K) | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | ||

| Unknown | 8030 | 7130 | None | CW (Y) and Mb (R, R) | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | ||

| Proteins specific to Garcera et al. study | ||||||||

| Pir1 | 5153 | 220 | D. hansenii protein | 62/49 | CW (L) | Hog1, fluconazole, iron, Efg1, Plc1 | ND (not tested) | By homology, involved in cell wall integrity |

| Unknown | 8954 | 7606 | None | Mb (K, R) | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | ||

| Unknown | 7675 | 5267 | None | Caspofungin | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | ||

| Unknown | 7427 | 4014 | ScCdc1 | 55/35 | Induced upon adherence to polystyrene | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | |

| Unknown | 5522 | 6329 | None | Mb (R, R, K) | Opaque specific; fluconazole, Cyr1 | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | |

| Unknown | 8449 | 7104 | None | CW (V) | ND (no mutant described) | Unknown | ||

This final list has been obtained by compiling data from three different in silico studies of the C. albicans genome, those from de Groot et al., Eisenhaber et al., and Garcera et al. (12, 16, 21). Boldface indicates a protein with a function related to cell-to-cell adhesion; italics indicate a protein with a function related to cell wall biogenesis or remodeling. ND, not determined.

The numbers in the orf6 and orf19 columns are the different numbers given to the same sequences through the steps of the C. albicans genome sequencing project.

A systematic search for homologues of the proteins has been done with each gene by using the NCBI BLASTP tool (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/). “None” indicates no hit; “D. hansenii protein” indicates a hit in the Debaryomyces hansenii genome; “C. glabrata protein” indicates a hit in the C. glabrata genome; other homologues were identified from matches with S. cerevisiae genes.

The percentages of identity and similarity between C. albicans sequences and the corresponding sequences from other fungi are given in the column.

Localization prediction: CW, cell wall; Mb, membrane. The residues found in the sequence that permitted the prediction are displayed in parentheses.

Data were extracted from transcriptional analyses, mainly using the Candida genome database website (http://www.candidagenome.org/).

Our final list consists of 115 putative GpiPs corresponding to the C. albicans genome (Table 1), 70 of which are common to the three published data sets, 6 of which are common to the data sets presented by de Groot et al. and Eisenhaber et al., 24 of which are specific to the study by de Groot et al. (12), 9 of which are specific to the study by Eisenhaber et al. (16), and 6 of which are specific to the study by Garcera et al. (21). The number of putative GpiPs identified in C. albicans (115) is almost twice that identified in S. cerevisiae (58 GpiPs); however, we should keep in mind that lists for both C. albicans and S. cerevisiae are the results of computerized predictions and may still retain some annotation artifacts.

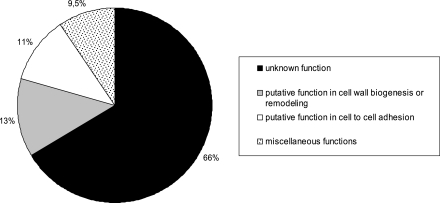

MORE THAN 65% OF THE GpiPs IN C. ALBICANS HAVE UNKNOWN FUNCTIONS

Looking at each putative GpiP provides us with very little functional information, as a vast majority of the proteins are of unknown function. Nevertheless, newly available genomic sequences and transcriptomic tools now allow us to make informed inferences about genes with unknown functions. Thus, among the 115 GpiPs identified from the C. albicans genome, four classes can be described (Fig. 2): (i) the GpiPs with completely unknown functions (corresponding to 76 genes, or 66% of the GpiP genes), (ii) the GpiPs with putative functions related to cell wall biogenesis or remodeling (corresponding to 15 genes, or ∼13%), (iii) the GpiPs with putative functions related to cell-cell adhesion and interactions (corresponding to 13 genes, or ∼11%), and (iv) the GpiPs with diverse enzymatic properties, such as superoxide dismutase activity and aspartyl protease activity, etc. (corresponding to 11 genes, or 9.5% altogether). The largest class, representing 66% of genes and having completely unknown functions, may be relevant to the future discovery of novel genes involved specifically in C. albicans pathogenicity. Firstly, because of the putative localization of GpiPs at the cell surface, they are in a very good position to be involved in any interaction with the surrounding environment, the host cells. Secondly, C. albicans is highly adapted to its environment compared to other opportunistic fungi (in terms of pH, oxidation, phagosomes, etc.), which suggests that during evolution it developed several mechanisms to colonize its host; these original functions might be carried out by these surface proteins of unknown function.

FIG. 2.

Function repartition within the group of GPI-anchored proteins (Table 1).

Careful analysis of the 76 proteins of unknown function reveals that 41 of them have been reported to be regulated by various transcription factors and conditions (Table 1). Rim101 is the most common regulator of these proteins; 22% of them are regulated by Rim101 (9 out of 41). Changes in iron levels, the morphogenetic switch, Nrg1, and Tup1, as well as cell wall regeneration, also regulate them; for each of the aforementioned regulators, we count eight genes (19.5%) reported to be regulated and six after caspofungin treatment. Even if this number is not statistically robust considering the sizes of the groups, these data might be worth further attention. For instance, in the literature, two papers report experimental data on the monitoring of the genes regulated by Rim101 (4, 34). The results vary between 132 (M.L.R., unpublished results) and 186 (4, 34) genes out of more than 5,000; thus, around 3% of the genome is regulated by Rim101, which is a much smaller amount than the 22% indicated in our data set. This finding would suggest that, as well as being involved in pH response, in adaptation to high salt concentrations, and in morphogenesis, Rim101 might also play a role in regulating the expression of some GpiPs. Alternatively, it is possible that GpiPs may simply have an important role in the three aforementioned functions. For example, the two glucanosyltransferases, Phr1 and Phr2, are both regulated by Rim101 and are essential for growth at alkaline and acidic pHs, respectively (10, 18).

FAMILIES WITHIN THE GROUP OF GPI-ANCHORED PROTEINS

In order to identify families within the GpiP gene group, we used BLASTP to compare each gene against the entire group. From this analysis, we identified eight families with only two members (Table 2). Interestingly, two of these gene couples are adjacent on the chromosome (families 1 and 8), which might be the result of a tandem duplication event during evolution. We identified six families with three members, two families with four members, and two families with at least eight members, the ALS genes and the HYR/IFF genes. This analysis indicates that within the GpiP group, more than 50% of the proteins (67 out of 115 proteins) have a paralogue. There are at least two hypotheses for the utility of a gene family in a genome: (i) the function carried out by the family is essential, and thus the redundancy of the genes protects the cell against any lethal loss in functionality, and (ii) the function carried out requires fine-tuning that proteins within the family can provide only if they are expressed under different conditions or if their affinities for diverse substrates are slightly different, for instance. A good example is the DFG5 family, where the DFG5 or PGA51/DCW1 gene is dispensable to the cell but the deletion of both genes is lethal in C. albicans (26), as is the deletion of the respective orthologues of these genes in S. cerevisiae (31), suggesting that the function carried out by these proteins is probably essential to the cell.

TABLE 2.

Families of genes corresponding to GpiPs of C. albicansa

| Family | Member genes |

|---|---|

| 1 | orf19.4652, orf19.4653 |

| 2 | CHT1, CHT2, CHT3 |

| 3 | DFG5, PGA51/DCW1 |

| 4 | ECM331, ECM33.3 |

| 5 | EXG2, SPR1, EXG1 |

| 6 | PGA37, PGA57 |

| 7 | PGA59, PGA62 |

| 8 | SAP9, SAP10, SAP1, SAP2, SAP3, SAP4, SAP5, SAP6, SAP7, SAP8 |

| 9 | CRH1, UTR2, CRH11 |

| 10 | PGA2/SOD4, PGA3/SOD5, PGA9/SOD6 |

| 11 | PGA15, PGA41, PGA42 |

| 12 | HWP1, RBT1, PGA8/HWP2 |

| 13 | PGA30, PGA31, PGA32, orf19.1745 |

| 14 | PLB3, PLB4, PLB5, PLB1, PLB2 |

| 15 | CSA1, PGA7, PGA10/RBT8, RBT5, orf19.3117 |

| 16 | PGA4/GAS1, PGA5/GAS2, PHR1, PHR2, PHR3 |

| 17 | ALS1, ALS2, ALS3, ALS4, ALS5, ALS6, ALS7, ALS9 |

| 18 | HYR1, IFF1, IFF2, IFF3, IFF4, IFF5, IFF6, IFF7, IFF8, IFF9, IFF10, IFF11 |

| 19 | PGA52, TOS1 |

| 20 | PGA24, orf19.3621 |

| 21 | orf19.4014, CDC1 |

| 22 | KRE1, KRE2 |

| 23 | orf19.220, orf19.2783 |

| 24 | YCK3, YCK2, HRR25 |

| 25 | PGA12, orf19.7596, orf19.6809, orf19.2607 |

Genes corresponding to predicted GpiPs are in bold; the other genes listed correspond to proteins that are not GPI anchored. Families have been classified according to a BLASTP analysis of C. albicans genome sequences.

In addition to families within the GpiP group, we looked for GpiP genes that could be members of gene families within the whole C. albicans genome. Our analysis indicated two types of scenarios (Table 2): (i) GpiP genes that belong to an “outside” family, that is, those including members other than GpiP genes (seven families), and (ii) GpiP genes that are already members of “inside” families but that also have paralogues outside of the GpiP gene group (eight families). For example, several gene families already characterized are heterogeneous: the product of CHT3 is not GPI anchored, while those of CHT1 and CHT2 are; the products of SAP9 and SAP10 are GPI anchored, but those of the eight other SAP genes (SAP1 through SAP8) are not; and the products of PLB1 and PLB2 are not GPI anchored, while those of PLB3 through PLB5 are.

With these heterogeneous families, it is difficult to assess whether the GPI anchor prediction was wrong in these cases or whether the cells use two proteins with similar functions but distinct localizations. Additionally, several GpiPs were found to have no GpiP homologues but instead one to four non-GpiP homologues (Table 2).

Our limited understanding of the functions and the regulation of these proteins hinders our abilities to interpret how C. albicans modulates its genome to end up with such diversity in localization. Nevertheless, it seems that the percentage of gene families within the GpiP group is relatively high, with many heterogeneous families composed of genes for proteins with or without GPI anchors.

One of the most studied GpiP gene families to date is the ALS (agglutinin-like sequence) family. The entire ALS family was first described in detail by Lois Hoyer in 2001 (26) as a family of genes homologous to the alpha-agglutinin genes of S. cerevisiae. Since then, numerous research papers on this family have been published; in the last 10 years at least 55 papers have discussed the expression or the roles of various ALS genes in C. albicans biology. An entire review would be necessary to discuss the data available for the ALS gene family of C. albicans; thus, we will try here to emphasize just two particularly interesting aspects of this family: the high potential for variation among the ALS gene sequences and the role of the ALS genes in virulence (see “GPI-Anchored Proteins, Cell Walls, and Virulence” below).

Looking closely at the sequences of all of the ALS proteins reveals that there is a high level of similarity among ALS family members both in nucleotide and corresponding peptide sequences, a similarity that also includes the upstream and downstream regions of the ORF. For example, sequences of ALS2 and ALS4 appear to be extremely close, as well as sequences of ALS1, ALS3, and ALS5.

An interesting point raised by several recent papers is the variation in ALS sequences between alleles of the same gene or in ALS sequences of the same gene among strains. In 2003, Zhang et al. studied ALS7 in 66 different strains of C. albicans and found 60 different forms of ALS7 generating 49 different genotypes (62). The domains of high variation in the corresponding proteins are the middle stretch of tandem repeats and the C-terminal portion containing VASES repeats. An analysis of the genotype data in parallel with the infection caused by the strains revealed that isolates representing a more pathogenic general-purpose genotype cluster tend to have more tandem repeats than other strains. In another study we learned that, in addition to differences in the sequences of the highly varied domain of tandem repeats, the two alleles of the same ALS gene (here ALS9) vary in the 5′ part of the ORF sequence (66).

There is also evidence suggesting that variation in the intragenic repeat numbers provides the cell a way to escape host defenses. Verstrepen and coworkers studied the variation generated by the intragenic tandem repeats in S. cerevisiae and showed that the variation in repeat size, occurring mostly in cell wall proteins, modifies the phenotypes of the strains (59). This finding suggests that these modifications, in addition to altering phenotypes, may also profoundly transform the antigenic properties of the cell, thus allowing the cell to deceive the immune system. Verstrepen et al. also proposed that the repeats are the site for recombination, thus favoring genetic reshuffling of domains and thereby creating cell surface proteins with new functions (60).

Sheppard and coworkers examined the structural diversity within the Als protein family (49). In this study, structural analyses of the sequence variations in the Als family confirmed again that these variations were likely responsible for the functional diversity within the family.

It seems that, even if the C. albicans genome includes eight ALS genes, in a given population there might be a higher number of different Als proteins on the cell surface, the result of slight sequence variations (differences in the numbers of tandem repeats and domain reshuffling, etc). That variation in size, sequence, structure, and consequently function might make our results with mutants of ALS tightly linked to the strain background we use and probably also the laboratory strain we are working with, since two CAI-4 isolates, for instance, may have evolved with time differently from laboratory to laboratory.

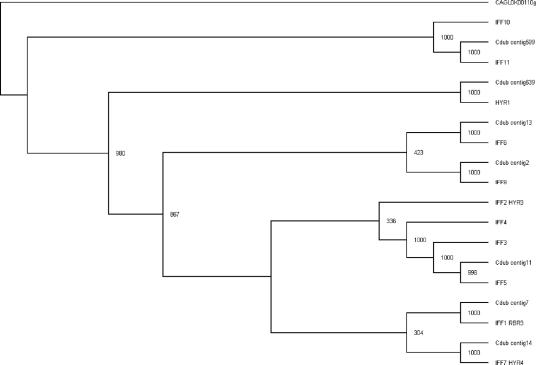

The largest family present in this GpiP gene class, with 12 genes, is the group of genes orthologous to HYR1 (for hyphally regulated), also known as the IFF genes (for individual protein file family F). As we noted above, 10 genes are predicted to have GPI anchors and two genes, IFF10 and IFF11, do not have any signal sequences for GPI anchor linkages. Very little is known about this family; only one member has been studied to date: HYR1 (3). This gene is strongly induced under conditions that trigger the morphogenetic switch. Mutant analysis, however, did not show a strong phenotype under the conditions tested. Analysis of the coding sequences in this family revealed gene products with a large N-terminal domain of 340 amino acids shared by each member of the family with high homology. The proteins diverge strongly after this domain, both in size and sequence. Phylogenetic analysis of this family shows that the two non-GPI-anchored proteins Iff10 and Iff11 diverge obviously from the original group but the others remain united. Interestingly, comparison with Candida dubliniensis sequences shows that C. albicans has a subgroup of IFF2, 3, 4, and 5 while C. dubliniensis has only one orthologue (Fig. 3). The tree representation suggests either that (i) C. dubliniensis has lost IFF2, 3, and 4 orthologues but kept the IFF5 orthologue or that (ii) in C. albicans, amplification of a gene from an IFF5 ancestor occurred. In either case, such differences might be one of the reasons explaining the difference in virulence levels of these two very close species (54). One can envision, for instance, that these proteins change the adherence properties of the cells and thus modify the capacity to colonize a specific environment.

FIG. 3.

Phylogenetic tree of the HYR/IFF gene family. The tree shows the relationships among Hyr1 and Iff proteins in C. albicans and C. dubliniensis (Cdub). This tree is based on protein sequence alignments of the first 350 amino acid residues after gap removal. For bootstrap analyses, we constructed this tree by the neighbor-joining method using ClustalX. Bootstrap values based on 1,000 replications are shown next to the nodes. An Iff homologue from C. glabrata was used as the out-group.

All these proteins possess serine/threonine-rich regions accounting for more than 30% of the sequence, as well as 8 to 48 N glycosylation sites; these characteristic suggest that these proteins are likely to be transferred to the cell wall. No function so far has been suggested for any of the Iff proteins, but the presence of the genes in 12 copies in the genome implies that they perform a useful function in terms of C. albicans biology, an idea reinforced by the fact that S. cerevisiae has no clear orthologue.

GPI-ANCHORED PROTEINS PRESENT AT THE CELL SURFACE

GpiPs in eukaryotes are largely thought to be localized only to the plasma membrane, although an alternate hypothesis (lacking direct experimental evidence thus far) is that a few of them may stay or be redirected to other cell compartments. A recent study of membrane lipid rafts in C. albicans shows that among the 29 proteins identified only 2 were GpiPs, Ecm33 and a Gas1 homologue (29), which seems surprisingly few compared to what was expected considering the results obtained with higher eukaryotes (48). A study of Cryptococcus neoformans, however, highlights the notion of enrichment with proteins in lipid rafts. Siafakas and coworkers also found only two GpiPs, but they were in much greater concentrations in lipid rafts than in the membrane (50). No quantitative data are yet available for C. albicans lipid rafts, but the situation might be comparable to that of C. neoformans: high concentration but low diversity.

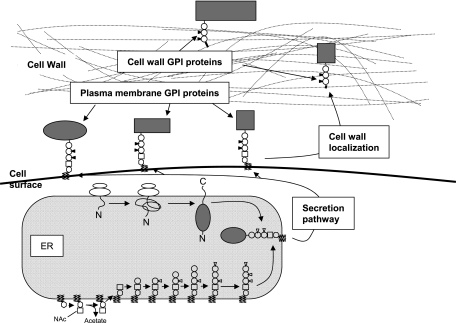

On the other hand, it has been shown with several fungi, S. cerevisiae and C. albicans in particular, that some of the GpiPs are released from the GPI anchor and are covalently bound to cell wall sugars, thus being only transiently localized at the plasma membrane (9). In S. cerevisiae, this cleavage event occurs between the N-acetylglucosamine group and the first mannose group of the anchor (Fig. 1); the protein with the GPI anchor remnant section is then transported to the cell wall network and linked to the β-1,6-glucans by an unidentified protein or protein complex. Figure 4 summarizes the different stages of synthesis and transport of a fungal GPI-anchored protein.

FIG. 4.

The different steps of the synthesis and transport of a GPI-anchored protein in yeasts or fungi. The first steps of GPI anchor biosynthesis occur in the ER or at its surface: synthesis of the GPI core structure and translation through the ER membrane of the future GpiP. The subsequent attachment of the protein onto the GPI anchor takes place in the ER lumen. Then the GpiPs follow the secretory pathway to be presented at the cell surface. The particularity of some fungi is an additional step in which the GPI anchor is cleaved after the glucosamine and the protein with the remnant part of the anchor is directed to the cell wall and covalently linked to β-1,6-glucan.

Based on studies with S. cerevisiae, there are few known sequence features common among the cell wall GpiPs. Two kinds of signal sequences for cellular localization in S. cerevisiae have been proposed: (i) the specific amino acid residues V, I, or L at the site ω-4 or ω-5 upstream of the GPI attachment site (the ω site) and Y or N at the site ω-2 for cell wall localization and (ii) dibasic residues, R and K, for instance, in the region upstream of the ω site for plasma membrane localization (25). No similar studies have been done with C. albicans, given that we can extrapolate from our knowledge of S. cerevisiae. We applied these signal sequence rules to the 115 GpiPs presented earlier in the review and to the 58 putative GpiPs listed by Caro et al. (9) for S. cerevisiae (Table 3). These rules of localization give similar results for S. cerevisiae and C. albicans, with equal percentages of cell wall and membrane-bound proteins, although in C. albicans the percentage of unclassified proteins is much higher, comprising almost half of the 115 proteins (46 proteins, or 40%). Such an analysis of Candida, however, is not necessarily consistent with experimental data. Dfg5, for example, contains several dibasic amino acids upstream of the predicted ω site. However, Spreghini et al. showed that Dfg5 is localized to the cell wall after cell fractionation and Western blotting (52). Again, if we try to predict the localization patterns of the 12 GpiPs identified in a proteomic analysis (see below), 2 are incorrectly predicted to be localized to the membrane, 4 are correctly predicted, and 6 are associated with no clear prediction (11). Thus, one cannot yet predict with confidence where a GpiP will be localized and experimental testing is still the only way to clearly know.

TABLE 3.

Prediction of GpiP localization in S. cerevisiae and C. albicans based on the amino acid environment of the ω-minus regiona

| Yeast | % of GpiPs with:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell wall localization | Membrane localization | Both localization patterns | No particular residues for prediction of localization | |

| C. albicans | 29 | 25 | 6 | 40 |

| S. cerevisiae | 43 | 45 | 2 | 7 |

Another approach to establishing the localization of cell wall GpiPs is to directly extract the cell wall and subsequently identify the GpiPs present. This strategy was used by investigators in the F. Klis laboratory; they prepared C. albicans cell walls cleared of weakly bound or unbound cell wall proteins and digested the glucan network to free the covalently bound cell wall proteins (11). This protein mix was then subjected to liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry analysis for protein identification. Interestingly, they identified only 14 proteins, 12 of which are GpiPs, supporting the idea that the “surfoproteome” is quite reduced. It is indeed highly surprising to identify 12 GpiPs on the cell wall when 115 are encoded by the genome, of which 30 to 50% are supposedly cell wall bound. There are at least three simple hypotheses to explain this finding. (i) The technique in itself needs a large amount of proteins in order to detect them and so the majority of the cell wall-bound proteins expressed at low levels are not distinguished from the background noise. (ii) The surfoproteome is highly dependent on environmental conditions, and so for each condition there is a specific pool of cell wall GpiPs. (iii) The last obvious hypothesis is that cell wall localization is a relatively rare event and that most GpiPs are indeed membrane bound. The first hypothesis is partially dismissed by de Groot and coworkers since they state that their technique allows them to identify cell wall proteins when there are about 500 molecules present per wall (∼0.05% of the covalently bound cell wall molecules), which is a rather small amount of protein (11). Concerning the second hypothesis, a study on the stability of cell wall protein pools was done in the laboratory of R. Sentandreu and the results support the idea that the turnover of cell wall proteins is very slow (47). Indeed, during the pulse-chase experiments conducted by Ruiz-Herrera et al., the investigators did not observe any protein recycling after 4.5 h of chase, suggesting that the proteins linked to the cell wall components are very stable. Considering the results reported in these two publications, it would be interesting to repeat the same type of experiments using a chase under completely different conditions. One may find a cell wall protein turnover that becomes induced by adaptations to external changes, such as pH or temperature.

GPI-ANCHORED PROTEINS, CELL WALLS, AND VIRULENCE

Cell surface proteins and virulence are often linked in the literature about both eukaryotes and prokaryote pathogens. To date, several GpiPs have been found to be involved in virulence, but it is not clear whether the effects are direct or not, since subsequent molecular analysis is often missing.

A global survey of the 115 GpiP genes tells us that for 87 genes no mutant exists, 13 mutants have been constructed but not tested in virulence assays, and of the 15 mutants tested, 3 exhibit normal virulence and 12 have reduced virulence compared to that of the corresponding reference strain (Table 1). The sample is too small to allow statistical comparison but still suggests that GpiPs probably support one or several aspects of C. albicans virulence traits. The small number of genes tested makes the classification difficult, but the virulence defect of the mutants can be explained by very different reasons, usually indirect consequences of the gene deletion. We propose the following subdivision.

Cell wall biosynthesis and modeling.

Phr1, Phr2, Utr2, Ecm33, and Cht1 are clearly linked to some aspect of the cell wall structure, which is critical in the cell cycle and often has important consequences for the capacity of C. albicans to switch from yeast to hyphae or vice versa, a well-known virulence trait. In addition, the modification of the cell wall structure or composition may change the surface epitope recognized by the host and thus modify the level of virulence.

Specific enzymatic functions.

The two aspartyl proteinases Sap9 and Sap10 seem to affect virulence through indirect effects on more-essential GpiPs, as was observed for a gpi7 null mutant (45, 46) (Gpi7 is responsible for the addition of a side chain to the GPI core structure [Fig. 1]). Indeed, in contrast to Sap1 through Sap6, which digest proteins surrounding the cell, Sap9 and Sap10 are involved in protein processing and activation, thus regulating protein function. While a mutant lacking gpi7 secretes GpiPs into the medium, mutants lacking SAP9 and SAP10 do not process essential proteins and thus block the functions of these proteins, but the consequences are the same: a defect in cytokinesis and a disorganized cell wall network (2).

A recent study of the phospholipase B family from C. albicans (five members) showed that strains lacking the GpiP Plb5 have a reduced level of in vivo organ colonization (56). It seems, however, that Plb5's role in pathogenesis is weaker than that of Plb1, a secreted non-GPI-anchored phospholipase B, since the phenotype is visible only in organ colonization for Plb5 (33, 40). The hypothesis for both proteins is that such secreted or cell-associated enzymes may be especially important while Candida is in close contact with host cells for the breakdown of the host cell membranes.

Rbt1 is one interesting target for further research, since the function of this protein is poorly understood, but its relation to infection is still unclear. Braun and coworkers suggest that it may interact with and impair the immune system of the host and thus the mutant lacking RBT1 would be cleared more easily during infection (8).

Oxidant adaptation.

Superoxide dismutase appears to be involved in virulence by increasing C. albicans resistance to the immune system. Mutants lacking SOD5 are more sensitive to neutrophils (19) but not to macrophage phagocytosis (35). The attenuated in vivo virulence of a sod5−/− mutant suggests that oxidative burst might be an important way to kill C. albicans and also confirms the crucial role of neutrophils in preventing candidiasis.

Adherence.

Other than the Als proteins, Hwp1 is one of the most studied proteins and probably the protein that fits best into the current virulence models. Moreover, Hwp1 and Als proteins both appear to act on the same aspect of C. albicans biology: interactions with cells. The ability of C. albicans to adhere to various constituents plays an important role in host colonization and in the initiation and maintenance of an infection.

The function of Hwp1 in interacting with host cells has been clearly demonstrated, since Hwp1 was shown to be the substrate of human transglutaminases that enable C. albicans to be cross-linked to host epithelial cells (53). Defects in adherence in this case and maybe in other types of interactions with the host impair the virulence of the strains.

Among the eight ALS genes present in the Candida genome, only ALS1 (20), ALS3 (64), ALS4 (65), and ALS7 (42) have been disrupted; as for ALS2, the gene seems to be essential to C. albicans viability (65). In the work of Zhao et al. with ALS1, ALS5, and ALS9 in 2003, only heterozygotes were produced but the investigators did not report the phenotypes (66). Of the four ALS gene deletion mutants of C. albicans, the als4 null mutant has wild-type virulence, the als7 null mutant has not been tested, and the als1 and als3 null mutants are described as having reduced virulence but in particular models (20, 64). The strain lacking ALS3 is defective in adherence to both endothelial and epithelial cells, reducing the destruction of the tissue in an in vitro model (64). As for ALS1, the deletion strain shows slightly reduced virulence in a mouse model and reduced adherence on mouse tongues (1, 30). The relatively weak effect of deleting ALS1 and ALS3 may be explained by the redundancy of functions in the ALS family.

In each case, the virulence is tightly link to a phenotype in adherence tests; only als1, als3, and als4 mutants have been tested for adherence and were found to be defective, thus confirming the hypothesis that at least part of the function of the ALS family is in cell-cell adherence (20, 64, 65). Strategies other than deletion were used to confirm the involvement of ALS proteins in the adhesion phenomenon. Als5 has been the subject of several studies in which the protein was expressed in S. cerevisiae, resulting in binding to a variety of substrates, extracellular matrix-coated beads, human buccal cells, epithelial cells, and various peptides, etc. (22, 23, 32). A recent study deciphered the role of Als protein domains by again using Als5 and S. cerevisiae. Rauceo and coworkers concluded that the N-terminal region contributes to cell adhesion activity through increased binding to fibronectin and that the central domain constituted of threonine-rich tandem repeats participates in cell-cell interactions (44). Finally, recent work confirms the role of Als3 in adhesion and in particular its crucial role during biofilm formation; in these studies, the investigators interestingly developed in vitro and, more importantly, in vivo models of biofilm formation (41, 43, 63).

CONCLUSION

GPI-anchored proteins in C. albicans represent an extraordinary group of proteins localized to the cell surface. A variety of phenomena occur at the plasma membrane or at the outer surface of a cell, including molecule and ion transport, ligand-receptor interactions, protein activation by enzymatic processing, glucan biosynthesis and destruction, and many types of host-pathogen interactions involving proteins and glucans. A thorough analysis of this special class of proteins would not have been possible without all of the recently published data and the availability of the sequence of the C. albicans genome.

There are 70 GPI-anchored proteins in C. albicans if we count only the ones in common among all the studies discussed or 115 if we combine the results these studies together. In both cases, the count is higher than that for S. cerevisiae, and it does not seem that this increase is only the consequence of the amplification of several gene families since between S. cerevisiae and C. albicans GpiP genes, families appear or increase in size but also disappear or reduce in size (for instance, FLO and TIR families in S. cerevisiae do not exist in C. albicans). This variation suggests that several unique attributes of C. albicans are likely to be encoded by these genes. This idea is reinforced by the high percentage of genes with unknown functions in this group, more than 65% of the group of 115 (and almost 65% of the group of 70); for S. cerevisiae, for instance, of the 58 predicted GpiPs (9), we find only 36% of these proteins to be without a known function by using Saccharomyces genome database tools (http://www.yeastgenome.org/). This comparison between C. albicans and S. cerevisiae has to be carefully used since it seems that the percentage of GpiPs of unknown function varies among fungi, with 60% for Aspergillus nidulans, 58% for Neurospora crassa, and 39% for Schizosaccharomyces pombe (16). It is interesting that among the proteins of unknown function, some are C. albicans specific and some are fungus specific; in either case, these proteins are of particular interest. The data set differs greatly in size and composition from S. cerevisiae GpiP lists, so the probability of finding targets original and specific to fungi increases. It is thus likely that by studying C. albicans GpiPs we will discover genes with functions that interest other scientific communities specializing in fungal human or plant pathogens like Aspergillus, Cryptococcus, Magnaporthe, or Ustilago, genes that we would not have unraveled by studying exclusively the model yeast S. cerevisiae.

In this review, we have shown the high heterogeneity of GpiPs in predictability of function, gene family arrangement, and cellular localization. The only general conclusion that we can draw so far is that GpiPs seem to be involved directly or indirectly in virulence through their functions in cell adhesion/cell recognition or cell wall biosynthesis and remodeling. Thus, there is still a lot to learn from the GPI-anchored proteins that may provide insight into the diagnosis and treatment of C. albicans infections. The recent publication on an Als1-based vaccine (27, 51) may give us a little glimpse into what the future will hold for us.

Acknowledgments

We thank Cécile Neuvéglise for assistance with the manipulation of genome sequences of C. albicans and phylogenic tree construction. We are grateful to Clarissa J. Nobile for her critical comments on the manuscript. We also thank the reviewers for their comments that greatly helped the improvement of our review.

Support for this research was provided by the INRA, and Armêl Plaine has an MNERT fellowship funded by the French government.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 22 December 2006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alberti-Segui, C., A. J. Morales, H. Xing, M. M. Kessler, D. A. Willins, K. G. Weinstock, G. Cottarel, K. Fechtel, and B. Rogers. 2004. Identification of potential cell-surface proteins in Candida albicans and investigation of the role of a putative cell-surface glycosidase in adhesion and virulence. Yeast 21:285-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albrecht, A., A. Felk, I. Pichova, J. R. Naglik, M. Schaller, P. de Groot, D. Maccallum, F. C. Odds, W. Schafer, F. Klis, M. Monod, and B. Hube. 2006. Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteases of Candida albicans target proteins necessary for both cellular processes and host-pathogen interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 281:688-694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bailey, D. A., P. J. Feldmann, M. Bovey, N. A. Gow, and A. J. Brown. 1996. The Candida albicans HYR1 gene, which is activated in response to hyphal development, belongs to a gene family encoding yeast cell wall proteins. J. Bacteriol. 178:5353-5360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bensen, E. S., S. J. Martin, M. Li, J. Berman, and D. A. Davis. 2004. Transcriptional profiling in Candida albicans reveals new adaptive responses to extracellular pH and functions for Rim101p. Mol. Microbiol. 54:1335-1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borner, G. H., D. J. Sherrier, T. J. Stevens, I. T. Arkin, and P. Dupree. 2002. Prediction of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins in Arabidopsis. A genomic analysis. Plant Physiol. 129:486-499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boutin, J. A. 1997. Myristoylation. Cell. Signal. 9:15-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bowman, S. M., A. Piwowar, M. Al Dabbous, J. Vierula, and S. J. Free. 2006. Mutational analysis of the glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor pathway demonstrates that GPI-anchored proteins are required for cell wall biogenesis and normal hyphal growth in Neurospora crassa. Eukaryot. Cell 5:587-600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braun, B. R., W. S. Head, M. X. Wang, and A. D. Johnson. 2000. Identification and characterization of TUP1-regulated genes in Candida albicans. Genetics 156:31-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caro, L. H., H. Tettelin, J. H. Vossen, A. F. Ram, H. van den Ende, and F. M. Klis. 1997. In silico identification of glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol-anchored plasma-membrane and cell wall proteins of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 13:1477-1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Bernardis, F., F. A. Muhlschlegel, A. Cassone, and W. A. Fonzi. 1998. The pH of the host niche controls gene expression in and virulence of Candida albicans. Infect. Immun. 66:3317-3325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Groot, P. W., A. D. de Boer, J. Cunningham, H. L. Dekker, L. de Jong, K. J. Hellingwerf, C. de Koster, and F. M. Klis. 2004. Proteomic analysis of Candida albicans cell walls reveals covalently bound carbohydrate-active enzymes and adhesins. Eukaryot. Cell 3:955-965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Groot, P. W., K. J. Hellingwerf, and F. M. Klis. 2003. Genome-wide identification of fungal GPI proteins. Yeast 20:781-796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dohlman, H. G. 2002. G proteins and pheromone signaling. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 64:129-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eisenhaber, B., P. Bork, and F. Eisenhaber. 2001. Post-translational GPI lipid anchor modification of proteins in kingdoms of life: analysis of protein sequence data from complete genomes. Protein Eng. 14:17-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eisenhaber, B., S. Maurer-Stroh, M. Novatchkova, G. Schneider, and F. Eisenhaber. 2003. Enzymes and auxiliary factors for GPI lipid anchor biosynthesis and post-translational transfer to proteins. Bioessays 25:367-385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eisenhaber, B., G. Schneider, M. Wildpaner, and F. Eisenhaber. 2004. A sensitive predictor for potential GPI lipid modification sites in fungal protein sequences and its application to genome-wide studies for Aspergillus nidulans, Candida albicans, Neurospora crassa, Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Schizosaccharomyces pombe. J. Mol. Biol. 337:243-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferguson, M. A. 1999. The structure, biosynthesis and functions of glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchors, and the contributions of trypanosome research. J. Cell Sci. 112:2799-2809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fonzi, W. A. 1999. PHR1 and PHR2 of Candida albicans encodes putative glycosidases required for proper cross-linking of beta-1,3- and beta-1,6-glucans. J. Bacteriol. 181:7070-7079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fradin, C., P. De Groot, D. MacCallum, M. Schaller, F. Klis, F. C. Odds, and B. Hube. 2005. Granulocytes govern the transcriptional response, morphology and proliferation of Candida albicans in human blood. Mol. Microbiol. 56:397-415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fu, Y., A. S. Ibrahim, D. C. Sheppard, Y. C. Chen, S. W. French, J. E. Cutler, S. G. Filler, and J. E. Edwards, Jr. 2002. Candida albicans Als1p: an adhesin that is a downstream effector of the EFG1 filamentation pathway. Mol. Microbiol. 44:61-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garcera, A., A. I. Martinez, L. Castillo, M. V. Elorza, R. Sentandreu, and E. Valentin. 2003. Identification and study of a Candida albicans protein homologous to Saccharomyces cerevisiae Ssr1p, an internal cell-wall protein. Microbiology 149:2137-2145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gaur, N. K., S. A. Klotz, and R. L. Henderson. 1999. Overexpression of the Candida albicans ALA1 gene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae results in aggregation following attachment of yeast cells to extracellular matrix proteins, adherence properties similar to those of Candida albicans. Infect. Immun. 67:6040-6047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gaur, N. K., R. L. Smith, and S. A. Klotz. 2002. Candida albicans and Saccharomyces cerevisiae expressing ALA1/ALS5 adhere to accessible threonine, serine, or alanine patches. Cell Commun. Adhes. 9:45-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Griffith, O. H., and M. Ryan. 1999. Bacterial phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C: structure, function, and interaction with lipids. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1441:237-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamada, K., H. Terashima, M. Arisawa, N. Yabuki, and K. Kitada. 1999. Amino acid residues in the omega-minus region participate in cellular localization of yeast glycosylphosphatidylinositol-attached proteins. J. Bacteriol. 181:3886-3889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoyer, L. L. 2001. The ALS gene family of Candida albicans. Trends Microbiol. 9:176-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ibrahim, A. S., B. J. Spellberg, V. Avenissian, Y. Fu, S. G. Filler, and J. E. Edwards, Jr. 2005. Vaccination with recombinant N-terminal domain of Als1p improves survival during murine disseminated candidiasis by enhancing cell-mediated, not humoral, immunity. Infect. Immun. 73:999-1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Inoue, N., Y. Murakami, and T. Kinoshita. 2003. Molecular genetics of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Int. J. Hematol. 77:107-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Insenser, M., C. Nombela, G. Molero, and C. Gil. 2006. Proteomic analysis of detergent-resistant membranes from Candida albicans. Proteomics 6(Suppl. 1):S74-S81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kamai, Y., M. Kubota, T. Hosokawa, T. Fukuoka, and S. G. Filler. 2002. Contribution of Candida albicans ALS1 to the pathogenesis of experimental oropharyngeal candidiasis. Infect. Immun. 70:5256-5258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kitagaki, H., H. Wu, H. Shimoi, and K. Ito. 2002. Two homologous genes, DCW1 (YKL046c) and DFG5, are essential for cell growth and encode glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored membrane proteins required for cell wall biogenesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Microbiol. 46:1011-1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klotz, S. A., N. K. Gaur, D. F. Lake, V. Chan, J. Rauceo, and P. N. Lipke. 2004. Degenerate peptide recognition by Candida albicans adhesins Als5p and Als1p. Infect. Immun. 72:2029-2034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leidich, S. D., A. S. Ibrahim, Y. Fu, A. Koul, C. Jessup, J. Vitullo, W. Fonzi, F. Mirbod, S. Nakashima, Y. Nozawa, and M. A. Ghannoum. 1998. Cloning and disruption of caPLB1, a phospholipase B gene involved in the pathogenicity of Candida albicans. J. Biol. Chem. 273:26078-26086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lotz, H., K. Sohn, H. Brunner, F. A. Muhlschlegel, and S. Rupp. 2004. RBR1, a novel pH-regulated cell wall gene of Candida albicans, is repressed by RIM101 and activated by NRG1. Eukaryot. Cell 3:776-784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martchenko, M., A. M. Alarco, D. Harcus, and M. Whiteway. 2004. Superoxide dismutases in Candida albicans: transcriptional regulation and functional characterization of the hyphal-induced SOD5 gene. Mol. Biol. Cell 15:456-467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mastrangelo, P., and D. Westaway. 2001. Biology of the prion gene complex. Biochem. Cell Biol. 79:613-628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mayor, S., and H. Riezman. 2004. Sorting GPI-anchored proteins. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5:110-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McConville, M. J., and A. K. Menon. 2000. Recent developments in the cell biology and biochemistry of glycosylphosphatidylinositol lipids (review). Mol. Membr. Biol. 17:1-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morita, T., N. Tanaka, A. Hosomi, Y. Giga-Hama, and K. Takegawa. 2006. An alpha-amylase homologue, aah3, encodes a GPI-anchored membrane protein required for cell wall integrity and morphogenesis in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 70:1454-1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mukherjee, P. K., K. R. Seshan, S. D. Leidich, J. Chandra, G. T. Cole, and M. A. Ghannoum. 2001. Reintroduction of the PLB1 gene into Candida albicans restores virulence in vivo. Microbiology 147:2585-2597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nobile, C. J., D. R. Andes, J. E. Nett, F. J. Smith, F. Yue, Q. T. Phan, J. E. Edwards, S. G. Filler, and A. P. Mitchell. 2006. Critical role of Bcr1-dependent adhesins in C. albicans biofilm formation in vitro and in vivo. PLoS Pathog. 2:e63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nobile, C. J., V. M. Bruno, M. L. Richard, D. A. Davis, and A. P. Mitchell. 2003. Genetic control of chlamydospore formation in Candida albicans. Microbiology 149:3629-3637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nobile, C. J., and A. P. Mitchell. 2005. Regulation of cell-surface genes and biofilm formation by the C. albicans transcription factor Bcr1p. Curr. Biol. 15:1150-1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rauceo, J. M., R. De Armond, H. Otoo, P. C. Kahn, S. A. Klotz, N. K. Gaur, and P. N. Lipke. 2006. Threonine-rich repeats increase fibronectin binding in the Candida albicans adhesin Als5p. Eukaryot. Cell 5:1664-1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Richard, M., P. De Groot, O. Courtin, D. Poulain, F. Klis, and C. Gaillardin. 2002. GPI7 affects cell-wall protein anchorage in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Candida albicans. Microbiology 148:2125-2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Richard, M., S. Ibata-Ombetta, F. Dromer, F. Bordon-Pallier, T. Jouault, and C. Gaillardin. 2002. Complete glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchors are required in Candida albicans for full morphogenesis, virulence and resistance to macrophages. Mol. Microbiol. 44:841-853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ruiz-Herrera, J., A. I. Martinez, and R. Sentandreu. 2002. Determination of the stability of protein pools from the cell wall of fungi. Res. Microbiol. 153:373-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sharom, F. J., and M. T. Lehto. 2002. Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins: structure, function, and cleavage by phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C. Biochem. Cell Biol. 80:535-549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sheppard, D. C., M. R. Yeaman, W. H. Welch, Q. T. Phan, Y. Fu, A. S. Ibrahim, S. G. Filler, M. Zhang, A. J. Waring, and J. E. Edwards, Jr. 2004. Functional and structural diversity in the Als protein family of Candida albicans. J. Biol. Chem. 279:30480-30489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Siafakas, A. R., L. C. Wright, T. C. Sorrell, and J. T. Djordjevic. 2006. Lipid rafts in Cryptococcus neoformans concentrate the virulence determinants phospholipase B1 and Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase. Eukaryot. Cell 5:488-498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spellberg, B. J., A. S. Ibrahim, V. Avenissian, S. G. Filler, C. L. Myers, Y. Fu, and J. E. Edwards, Jr. 2005. The anti-Candida albicans vaccine composed of the recombinant N terminus of Als1p reduces fungal burden and improves survival in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised mice. Infect. Immun. 73:6191-6193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Spreghini, E., D. A. Davis, R. Subaran, M. Kim, and A. P. Mitchell. 2003. Roles of Candida albicans Dfg5p and Dcw1p cell surface proteins in growth and hypha formation. Eukaryot. Cell 2:746-755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Staab, J. F., S. D. Bradway, P. L. Fidel, and P. Sundstrom. 1999. Adhesive and mammalian transglutaminase substrate properties of Candida albicans Hwp1. Science 283:1535-1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sullivan, D., and D. Coleman. 1997. Candida dubliniensis: an emerging opportunistic pathogen. Curr. Top. Med. Mycol. 8:15-25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sundstrom, P. 2002. Adhesion in Candida spp. Cell. Microbiol. 4:461-469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Theiss, S., G. Ishdorj, A. Brenot, M. Kretschmar, C. Y. Lan, T. Nichterlein, J. Hacker, S. Nigam, N. Agabian, and G. A. Kohler. 2006. Inactivation of the phospholipase B gene PLB5 in wild-type Candida albicans reduces cell-associated phospholipase A(2) activity and attenuates virulence. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 296:405-420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thomas, J. R., R. A. Dwek, and T. W. Rademacher. 1990. Structure, biosynthesis, and function of glycosylphosphatidylinositols. Biochemistry 29:5413-5422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tiede, A., I. Bastisch, J. Schubert, P. Orlean, and R. E. Schmidt. 1999. Biosynthesis of glycosylphosphatidylinositols in mammals and unicellular microbes. Biol. Chem. 380:503-523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Verstrepen, K. J., A. Jansen, F. Lewitter, and G. R. Fink. 2005. Intragenic tandem repeats generate functional variability. Nat. Genet. 37:986-990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Verstrepen, K. J., T. B. Reynolds, and G. R. Fink. 2004. Origins of variation in the fungal cell surface. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2:533-540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Weig, M., L. Jansch, U. Gross, C. G. De Koster, F. M. Klis, and P. W. De Groot. 2004. Systematic identification in silico of covalently bound cell wall proteins and analysis of protein-polysaccharide linkages of the human pathogen Candida glabrata. Microbiology 150:3129-3144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang, N., A. L. Harrex, B. R. Holland, L. E. Fenton, R. D. Cannon, and J. Schmid. 2003. Sixty alleles of the ALS7 open reading frame in Candida albicans: ALS7 is a hypermutable contingency locus. Genome Res. 13:2005-2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhao, X., K. J. Daniels, S. H. Oh, C. B. Green, K. M. Yeater, D. R. Soll, and L. L. Hoyer. 2006. Candida albicans Als3p is required for wild-type biofilm formation on silicone elastomer surfaces. Microbiology 152:2287-2299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhao, X., S. H. Oh, G. Cheng, C. B. Green, J. A. Nuessen, K. Yeater, R. P. Leng, A. J. Brown, and L. L. Hoyer. 2004. ALS3 and ALS8 represent a single locus that encodes a Candida albicans adhesin; functional comparisons between Als3p and Als1p. Microbiology 150:2415-2428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhao, X., S. H. Oh, K. M. Yeater, and L. L. Hoyer. 2005. Analysis of the Candida albicans Als2p and Als4p adhesins suggests the potential for compensatory function within the Als family. Microbiology 151:1619-1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhao, X., C. Pujol, D. R. Soll, and L. L. Hoyer. 2003. Allelic variation in the contiguous loci encoding Candida albicans ALS5, ALS1 and ALS9. Microbiology 149:2947-2960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]