Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the changes in anti‐cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies (anti‐CCP) and rheumatoid factor (RF) following etanercept treatment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

Methods

The study included 90 patients with rheumatoid arthritis who failed treatment with disease modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs). All patients were allowed to continue treatment with DMARDs; 52 of them received etanercept as a twice weekly 25 mg subcutaneous injection for three months, and the others did not. Serum samples were collected at baseline and one month intervals during the treatment course. The serum levels of anti‐CCP and RF were tested by enzyme linked immunosorbent assay and nephelometry, respectively.

Results

At baseline, 45 of the 52 etanercept treated patients (86.5%) and 32 of the 38 controls (84.2%) were positive for anti‐CCP. Tests for RF were positive in 78.9% and 84.2% of patients with or without etanercept treatment, respectively. The serum levels of anti‐CCP and RF decreased significantly after a three month etanercept treatment (p = 0.007 and p = 0.006, respectively). The average decrease from baseline calculated for each individual patient in the etanercept treated group was 31.3% for anti‐CCP and 36% for RF. The variation in anti‐CCP was positively correlated with the variation in disease activity, swollen and tender joint counts, RF, and C reactive protein.

Conclusions

Etanercept combined with DMARDs leads to a much greater decrease than DMARDs alone in the serum levels of anti‐CCP and RF in rheumatoid arthritis, compatible with a reduction in clinical disease activity.

Keywords: etanercept, cyclic citrullinated peptide, rheumatoid factor, rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis is a systemic autoimmune disease characterised by chronic joint inflammation that eventually results in bone destruction and severe disability. Disease modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) may retard disease progression.1 However, not all patients with rheumatoid arthritis can tolerate or respond to the traditional DMARDs.2 In recent years, advances in molecular technology have contributed to direct specific treatment aimed at relevant proinflammatory cytokines, such as tumour necrosis factor α (TNFα) and interleukin 1 (IL1). Etanercept, a soluble TNFα receptor fusion protein, can bind and neutralise extracellular TNFα. It has been shown to have marked clinical efficacy with minimal toxicity in rheumatoid arthritis patients who have an inadequate response to conventional DMARD treatment.3,4,5

The diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis depends primarily on the clinical manifestations of the disease, with only limited serological support. Rheumatoid factor (RF), the only serologic marker in routine use, is detectable only in ∼70% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis, and may be present in other diseases.6 Another diagnostic test for rheumatoid arthritis, the assay for anti‐cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies (anti‐CCP), has been developed in recent years. These antibodies are directed to proteins that contain the unusual amino acid citrulline, which is derived from the post‐translational modification of arginine by peptidylarginine deiminases.7 Anti‐CCP is useful in the preclinical and early diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis.8,9,10,11 It is also important for the prediction of disease severity and radiographic joint damage.12,13,14,15,16 The recently developed enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), used for detecting anti‐CCP, has a high specificity (89–96%) and reasonable sensitivity (65–88%) in the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis.17,18,19 The high disease specificity and frequent early presence of anti‐CCP suggest that this antibody plays an important role in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis.

It is evident that etanercept is effective in relieving the signs and symptoms and radiological outcome of patients with active rheumatoid arthritis.20,21 However, the changes in serum anti‐CCP levels during etanercept treatment have not been evaluated before. In the present study, therefore, we investigated whether this new biological agent, etanercept, has a significant impact on anti‐CCP antibodies as well as RF in rheumatoid patients who have an inadequate response to DMARDs. Complete clinical disease activity and serological indices were evaluated before and after treatment.

Methods

Patients

We studied 90 patients who had rheumatoid arthritis, as defined by American College of Rheumatology criteria.22 All candidates had failed treatment with methotrexate and another DMARD course (hydroxychloroquine, azathioprine, ciclosporine, sulfasalazine, or lefunomide), based on the British Society for Rheumatology guidelines for prescribing TNFα blockers in adult rheumatoid patients.23 No biological agents had been used in these patients, and DMARDs, corticosteroids (⩽10 mg of prednisolone), and non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) had to have been given at a stable dose for at least four weeks before and during the treatment course. After obtaining informed consent from the patients, we used an unbalanced design which involved a 4:3 random allocation procedure to obtain the most information about the new treatment. Thus all patients were then randomly assigned into two groups: 52 in the etanercept group (DMARDs with etanercept) and 38 in the control group (DMARDs without etanercept). Patients in the etanercept group received a subcutaneous injection of etanercept at a dose of 25 mg twice weekly for three months. The DMARDs received by these rheumatoid patients were similar between those with or without etanercept, and included methotrexate (89% v 92%), sulfasalazine (77% v 79%), hydroxychloroquine (58% v 53%), ciclosporine, leflunomide, and azathioprine (less than 10%). The clinical disease activity of the patients was evaluated before and after treatment by a trained nurse without knowledge of the treatment arm. The results were recorded with a 28 joint disease activity score (DAS28) which included the total number of tender and swollen joints, plus the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and the general health status.24 Serum samples were obtained from all patients at baseline and one month intervals during the treatment, and stored at −80°C until analysed.

Measurement of anti‐CCP and RF

We used the commercially available second generation ELISA test for anti‐CCP (Diastat, Axis Shield Diagnostics, Dundee, UK). The assay was carried out according to the manufacturer's instructions. All assays were done in duplicate. The results of the anti‐CCP test were considered positive if the antibody level was greater than the cut off value (5 U/ml). RF was measured by laser nephelometry for the IgM isotype (Date Behring, Marburg, Germany), and a level >20 IU/ml was considered positive. For both assays, in those cases in which the antibody level was too high for the optical densities to fall on a standard curve for the original dilution, samples were further diluted until an acceptable range for detection could be read. Acute phase reactants were measured by ESR (mm/h) and C reactive protein (mg/dl) using standard laboratory methods. We also used the ELISA kit to test for anti‐CCP in samples from 30 normal human blood donors to verify the specificity.

Statistical analysis

Data were summarised as the median and range for continuous variables, and as proportions for categorical variables. Comparison of the variables in the control and etanercept treated groups was done using the Mann–Whitney U test (in view of the non‐normal distribution of the results). The changes from baseline to follow up of study variables among the control and etanercept treated groups (intragroup analysis) were measured with Wilcoxon's signed rank test. The correlation analysis was made using Spearman's test. Differences were considered statistically significantly where p<0.05. Statistical analyses were carried out using the SAS statistical package.

Results

Patients

The baseline demographic characteristics of the patients were similar between the two groups (table 1). The changes in the main clinical and laboratory indices before and after treatment in the two groups are summarised in tables 2 and 3. The baseline variables were not significantly different between the two groups.

Table 1 Disease related characteristics of 90 patients with rheumatoid arthritis with or without etanercept.

| Characteristic | Etanercept group (n = 52) | Control group (n = 38) | p Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 53 (20 to 80) | 52 (20 to 69) | 0.223 | |||

| Women (%) | 90 | 87 | ||||

| Duration of disease (years) | 9.5 (1 to 20) | 8 (1 to 21) | 0.882 | |||

| Methotrexate (mg) | 7.5 (0 to 20) | 7.5 (0 to 20) | 0.551 | |||

| DMARDs except methotrexate (n) | 1.5 (1 to 3) | 1 (1 to 3) | 0.954 |

Values are median (range).

DMARD, disease modifying antirheumatic drug.

Table 2 Changes in the main clinical features before and after treatment in the etanercept and control groups.

| Variable | Etanercept group (n = 52) | Control group (n = 38) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month 0 | Month 3 | p Value | Month 0 | Month 3 | p Value | |||||||

| DAS28 | 6.2 (3.0 to 9.1) | 3.2 (0.3 to 7.1) | <0.001* | 6.2 (3.1 to 8.4) | 5.9 (3.0 to 8.3) | 0.053 | ||||||

| Swollen joints | 6 (1 to 25) | 2 (0 to 11) | <0.001* | 7.5 (0 to 25) | 7 (0 to 27) | 0.548 | ||||||

| Tender joints | 9.5 (0 to 28) | 2 (0 to 18) | <0.001* | 12 (1 to 26) | 11 (1 to 28) | 0.667 | ||||||

Values are shown as median (range).

*Significant difference.

DAS28, 28 joint disease activity score.

Table 3 Changes in the laboratory tests before and after treatment in the etanercept and control groups.

| Variable | Etanercept group (n = 52) | Control group (n = 38) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month 0 | Month 3 | p Value | Month 0 | Month 3 | p Value | |||||||

| Anti‐CCP (U/ml) | 60 (1 to 3099) | 49 (1 to 1438) | 0.007* | 118 (1 to 3098) | 101 (1 to 1200) | 0.648 | ||||||

| RF (IU/ml) | 87 (10 to 3170) | 64 (0 to 1440) | 0.006* | 95 (10 to 2580) | 76 (10 to 1290) | 0.091 | ||||||

| ESR (mm/h) | 43 (7 to 123) | 11 (1 to 77) | <0.001* | 39 (3 to 120) | 32 (1 to 124) | 0.355 | ||||||

| CRP (mg/dl) | 1.5 (0 to 11.5) | 0.1 (0 to 6.25) | <0.001* | 1.7 (0 to 8.39) | 1.1 (0 to 12.2) | 0.555 | ||||||

Values are median (range).

*Significant difference.

Anti‐CCP, anti‐cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies; CRP, C reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; RF, rheumatoid factor.

Clinical response

Patients treated with three months of etanercept and DMARDs achieved a more substantial clinical response than those treated with DMARDs alone at the end point, as defined by changes in DAS28 (table 2). The reduction of DAS28 in the etanercept group was significant, while there was a borderline decrease in the control group.

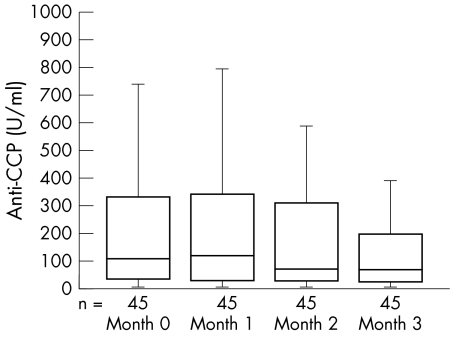

Anti‐CCP

In all, 86.5% and 84.2%, respectively, of those in the etanercept and control groups at baseline were positive for anti‐CCP. None of the 30 normal individuals were positive for anti‐CCP antibodies. The positive or negative characteristics of anti‐CCP remained essentially unaltered during the treatment with etanercept or DMARDs. A strong correlation between the levels of anti‐CCP and RF at baseline was observed (r = 0.291, p = 0.005). The serum level of anti‐CCP decreased significantly only in those patients who received a three month etanercept treatment (table 3). After the exclusion of the seven anti‐CCP negative patients in the etanercept group, the average decrease from baseline calculated for each individual patient was 31.3% for anti‐CCP, and the reduction was progressive throughout the etanercept treatment course (fig 1). The variation in anti‐CCP levels was positively correlated with the variation in DAS28 (r = 0.378, p<0.001), swollen joint count (r = 0.255, p = 0.015), tender joint count (r = 0.339, p = 0.001), RF (r = 0.406, p<0.001), and C reactive protein (r = 0.389, p<0.001), but not with the variation in ESR (r = 0.193, p = 0.069).

Figure 1 Changes of serum anti‐cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies (anti‐CCP) levels during the three month etanercept treatment in 45 anti‐CCP positive patients with rheumatoid arthritis. The lines in the boxes indicate median points; the edges of the boxes indicate the lower and upper quartile points.

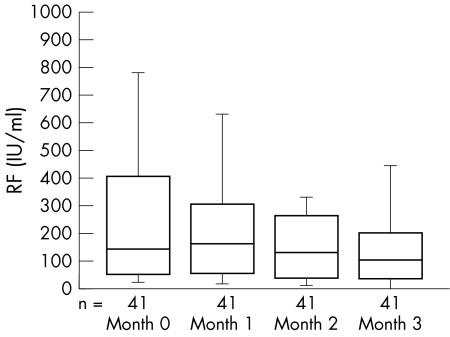

RF and acute phase reactants

At baseline, 41 of the 52 patients (78.9%) in the etanercept group and 32 of the 38 patients (84.2%) in the control group were positive for RF. Seven patients in the etanercept group and three in the control group with low levels of RF became negative during the treatment course. There was a significant decrease of RF in the group treated with etanercept (table 3), and the average decline from baseline was 36% for RF positive patients. The decrease in RF levels was also progressive throughout the course of the three month etanercept treatment (fig 2). The inflammatory markers ESR and C reactive protein decreased dramatically, beginning in the first month, and this decrease persisted throughout the etanercept treatment course.

Figure 2 Changes of serum rheumatoid factor (RF) levels during the three month etanercept treatment in 41 RF positive rheumatoid patients. The lines in the boxes indicate median points; the edges of the boxes indicate the lower and upper quartile points.

Discussion

This three month trial provides evidence for an obvious reduction in the disease activity and autoantibody production of rheumatoid patients in response to DMARDs combined with etanercept. These patients had longstanding rheumatoid arthritis (mean duration, 7.6 years), and all had been treated with methotrexate, the drug of first choice among the current DMARDs. The addition of etanercept provided more benefit without potentiating the toxic effects of DMARDs. Previous studies have shown that the regimen of etanercept plus methotrexate is more effective at reducing clinical activity and retarding radiographic progression than methotrexate alone in rheumatoid patients.4,25 Etanercept as monotherapy has also been shown to be superior to methotrexate in reducing disease activity and retarding radiographic destruction in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis.20,21 The clinical response to etanercept is rapid, generally occurring within two weeks, and nearly always within three months after the initiation of treatment.3,26 Our trial results showed that etanercept with DMARDs offered more advantages in terms of clinical symptoms and signs, inflammatory indices, and autoantibody levels than DMARDs alone.

With its high specificity, anti‐CCP plays an important role in the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis.17,18,19 The presence of anti‐CCP is associated with radiographic erosion and damage in rheumatoid arthritis.12,13,14,15,16 Infliximab, a chimeric anti‐TNFα monoclonal antibody, has been reported to reduce the anti‐CCP levels in rheumatoid patients who had a good clinical response after six months of infliximab treatment.27 However, other studies did not obtain the same findings at weeks 22 and 30 of infliximab treatment.28,29 Even the serological reduction of anti‐CCP during infliximab treatment (at week 30) could return to baseline with a longer duration of follow up (at weeks 54 and 78).30 It has been reported that a shorter disease duration (⩽12 months) predicts a greater reduction in anti‐CCP antibody levels with conventional treatment.31 The mean level of anti‐CCP has also been reported to decline during the three year follow up of DMARDs treatment in early onset rheumatoid arthritis (⩽12 months).15 In our three month study, only four and seven rheumatoid patients had a disease duration less than one year in the control and etanercept groups, respectively. The anti‐CCP variations were similar between patients with a disease duration longer than or shorter than one year in groups with or without etanercept. The effect of etanercept on anti‐CCP antibodies was not consistent with that of most previous studies of infliximab. Except for the difference between infliximab and etanercept, other factors such as the disease duration might play a role in the modulation of anti‐CCP production during anti‐TNFα treatment.

IgM‐RF is also an important predictor of radiographic damage in rheumatoid arthritis.32 Previous studies have reported that the levels of IgM‐RF antibodies could be reduced following infliximab treatment.27,28,29,30 In this trial, the progressive decrease of IgM‐RF levels in etanercept treated patients may have some prognostic importance. Acute phase reactants such as ESR and C reactive protein are very sensitive to change in disease activity. The levels of ESR and C reactive protein in the study decreased rapidly, beginning in the first month after the injection, and these reductions appeared to be sustained throughout the etanercept treatment. Similar results were observed with another TNFα blocker, infliximab.33

The mechanism of etanercept that blocks the production of these autoantibodies is still unknown. The pivotal role of TNFα in the inflammatory and proliferative processes of rheumatoid arthritis has been established. Except for the inhibition of TNFα activity, etanercept significantly reduces the number of peripheral blood mononuclear cells secreting IL1β, IL6, and interferon γ.34 High levels of IL13 in rheumatoid sera have also been modulated by etanercept.35 Etanercept is able to induce cell type specific apoptosis in the synovial monocyte/macrophage population and to decrease the number of these inflammatory cells in rheumatoid joints.36 These anti‐inflammatory effects may account for the reduction in acute phase reactants and autoantibody generation. However, more studies are needed to confirm and elucidate the role of etanercept in reducing these autoantibodies.

In this study, we showed a significant decrease in the levels of anti‐CCP and RF in the sera of rheumatoid patients after three months of etanercept treatment. While a reduction in the anti‐CCP level after infliximab treatment was not found to be concordant with previous studies, this is the first evidence of the downregulation of this specific antibody following etanercept treatment. The effect of etanercept on anti‐CCP and RF production may reflect an important therapeutic action of this agent. However, this study was limited to a three month observation and a relatively small group of patients. A longer follow up in a larger scale trial is necessary to further confirm the influence of etanercept on anti‐CCP and RF in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

Abbreviations

CCP - cyclic citrullinated peptide

DAS28 - 28 joint disease activity score

DMARD - disease modifying antirheumatic drug

ELISA - enzyme linked immunosorbent assay

ESR - erythrocyte sedimentation rate

IL - interleukin

RA - rheumatoid arthritis

RF - rheumatoid factor

TNFα - tumour necrosis factor α

References

- 1.Fries J F, Williams C A, Morfeld D, Singh G, Sibley J. Reduction in long‐term disability in patients with rheumatoid arthritis by disease‐modifying antirheumatic drug‐based treatment strategies. Arthritis Rheum 199639616–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cash J M, Klippel J H. Second‐line drug therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 19943301368–1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moreland L W, Baumgartner S W, Schiff M H, Tindall E A, Fleischmann R M, Weaver A L.et al Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with a recombinant human tumor necrosis factor receptor (p75)‐Fc fusion protein. N Engl J Med 1997337141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weinblatt M E, Kremer J M, Bankhurst A D, Bulpitt K J, Fleischmann R M, Fox R I.et al A trial of etanercept, a recombinant tumor necrosis factor receptor:Fc fusion protein, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving methotrexate. N Engl J Med 1999340253–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moreland L W, Schiff M H, Baumgartner S W, Tindall E A, Fleischmann R M, Bulpitt K J.et al Etanercept therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 1999130478–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tighe H, Carson D A. Rheumatoid factor. In: Harris ED, Budd RC, Genovese MC, Firestein GS, Sergent JS, Sledge CB, Ruddy S, eds. Kelley's textbook of rheumatology. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders, 2005301–310.

- 7.Vossenaar E R, Radstake T R, van der Heijden A, van Mansum M A, Dieteren C, de Rooij D J.et al Expression and activity of citrullinating peptidylarginine deiminase enzymes in monocytes and macrophages. Ann Rheum Dis 200463373–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jansen A L, van der Horst‐Bruinsma I, van Schaardenburg D, van de Stadt R J, de Koning M H, Dijkmans B A. Rheumatoid factor and antibodies to cyclic citrullinated Peptide differentiate rheumatoid arthritis from undifferentiated polyarthritis in patients with early arthritis. J Rheumatol 2002292074–2076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rantapaa‐Dahlqvist S, de Jong B A, Berglin E, Hallmans G, Wadell G, Stenlund H.et al Antibodies against cyclic citrullinated peptide and IgA rheumatoid factor predict the development of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2003482741–2749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nielen M M, van Schaardenburg D, Reesink H W, van de Stadt R J, van der Horst‐Bruinsma I E, de Koning M H.et al Specific autoantibodies precede the symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis: a study of serial measurements in blood donors. Arthritis Rheum 200450380–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raza K, Breese M, Nightingale P, Kumar K, Potter T, Carruthers D M.et al Predictive value of antibodies to citrullinated peptide in patients with very early inflammatory arthritis. J Rheumatol 200532231–238. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kroot E J, de Jong B A, van Leeuwen M A, Swinkels H, van den Hoogen F H, van't Hof M.et al The prognostic value of anti‐cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody in patients with recent‐onset rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2000431831–1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meyer O, Labarre C, Dougados M, Goupille P, Cantagrel A, Dubois A.et al Anticitrullinated protein/peptide antibody assays in early rheumatoid arthritis for predicting five‐year radiographic damage. Ann Rheum Dis 200362120–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jansen L M, van Schaardenburg D, van der Horst‐Bruinsma I, van der Stadt R J, de Koning M H, Dijkmans B A. The predictive value of anti‐cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies in early arthritis. J Rheumatol 2003301691–1695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kastbom A, Strandberg G, Lindroos A, Skogh T. Anti‐CCP antibody test predicts the disease course during 3 years in early rheumatoid arthritis (the Swedish TIRA project). Ann Rheum Dis 2004631085–1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forslind K, Ahlmen M, Eberhardt K, Hafstrom I, Svensson B. Prediction of radiological outcome in early rheumatoid arthritis in clinical practice: role of antibodies to citrullinated peptides (anti‐CCP). Ann Rheum Dis 2004631090–1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suzuki K, Sawada T, Murakami A, Matsui T, Tohma S, Nakazono K.et al High diagnostic performance of ELISA detection of antibodies to citrullinated antigens in rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol 200332197–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee D M, Schur P H. Clinical utility of the anti‐CCP assay in patients with rheumatic diseases. Ann Rheum Dis 200362870–874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dubucquoi S, Solau‐Gervais E, Lefranc D, Marguerie L, Sibilia J, Goetz J.et al Evaluation of anti‐citrullinated filaggrin antibodies as hallmarks for the diagnosis of rheumatic diseases. Ann Rheum Dis 200463415–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bathon J M, Martin R W, Fleischmann R M, Tesser J R, Schiff M H, Keystone E C.et al A comparison of etanercept and methotrexate in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 20003431586–1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Genovese M C, Bathon J M, Martin R W, Fleischmann R M, Tesser J R, Schiff M H.et al Etanercept versus methotrexate in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: two‐year radiographic and clinical outcomes. Arthritis Rheum 2002461443–1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arnett F C, Edworthy S M, Bloch D A, McShane D J, Fries J F, Cooper N S.et al The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 198831315–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ledingham J, Deighton C. British Society for Rheumatology Standards, Guidelines and Audit Working Group. Update on the British Society for Rheumatology guidelines for prescribing TNFalpha blockers in adults with rheumatoid arthritis (update of previous guidelines of April 2001). Rheumatology (Oxford) 200544157–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prevoo M L, van't Hof M A, Kuper H H, van Leeuwen M A, van de Putte L B, van Riel P L. Modified disease activity scores that include twenty‐eight‐joint counts. Development and validation in a prospective longitudinal study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 19953844–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klareskog L, van der Heijde D, de Jager J P, Gough A, Kalden J, Malaise M.et al Therapeutic effect of the combination of etanercept and methotrexate compared with each treatment alone in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: double‐blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2004363675–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keystone E C, Schiff M H, Kremer J M, Kafka S, Lovy M, DeVries T.et al Once‐weekly administration of 50 mg etanercept in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: results of a multicenter, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 200450353–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alessandri C, Bombardieri M, Papa N, Cinquini M, Magrini L, Tincani A.et al Decrease of anti‐cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies and rheumatoid factor following anti‐TNFalpha therapy (infliximab) in rheumatoid arthritis is associated with clinical improvement. Ann Rheum Dis 2004631218–1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Rycke L, Verhelst X, Kruithof E, Van den Bosch F, Hoffman I E, Veys E M.et al Rheumatoid factor, but not anti‐cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies, is modulated by infliximab treatment in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 200564299–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Caramaschi P, Biasi D, Tonolli E, Pieropan S, Martinelli N, Carletto A.et al Antibodies against cyclic citrullinated peptides in patients affected by rheumatoid arthritis before and after infliximab treatment. Rheumatol Int. Published Online First: 23 February 2005, doi: 10. 1007/s00296‐004‐0571‐9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Bobbio‐Pallavicini F, Alpini C, Caporali R, Avalle S, Bugatti S, Montecucco C. Autoantibody profile in rheumatoid arthritis during long‐term infliximab treatment. Arthritis Res Ther 20046R264–R272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mikuls T R, O'Dell J R, Stoner J A, Parrish L A, Arend W P, Norris J M.et al Association of rheumatoid arthritis treatment response and disease duration with declines in serum levels of IgM rheumatoid factor and anti‐cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody. Arthritis Rheum 2004503776–3782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bukhari M, Lunt M, Harrison B J, Scott D G, Symmons D P, Silman A J. Rheumatoid factor is the major predictor of increasing severity of radiographic erosions in rheumatoid arthritis: results from the Norfolk Arthritis Register Study, a large inception cohort. Arthritis Rheum 200246906–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kavanaugh A, St Clair E W, McCune W J, Braakman T, Lipsky P. Chimeric anti‐tumor necrosis factor‐alpha monoclonal antibody treatment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving methotrexate therapy. J Rheumatol 200027841–850. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schotte H, Schluter B, Willeke P, Mickholz E, Schorat M A, Domschke W.et al Long‐term treatment with etanercept significantly reduces the number of proinflammatory cytokine‐secreting peripheral blood mononuclear cells in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 200443960–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tokayer A, Carsons S E, Chokshi B, Santiago‐Schwarz F. High levels of interleukin 13 in rheumatoid arthritis sera are modulated by tumor necrosis factor antagonist therapy: association with dendritic cell growth activity. J Rheumatol 200229454–461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Catrina A I, Trollmo C, af Klint E, Engstrom M, Lampa J, Hermansson Y.et al Evidence that anti‐tumor necrosis factor therapy with both etanercept and infliximab induces apoptosis in macrophages, but not lymphocytes, in rheumatoid arthritis joints: extended report. Arthritis Rheum 20055261–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]