Abstract

Background

Osteoporotic hip fractures have been extensively studied in women, but they have been relatively ignored in men.

Objective

To study the mortality, morbidity, and impact on health related quality of life of male hip fractures.

Methods

100 consecutive men aged 50 years and over, with incident low trauma hip fracture, admitted to Royal Cornwall Hospital, UK during 1995–97, were studied. 100 controls were recruited from a nearby general practice. Mortality and morbidity, including health status assessed using the SF‐36, were evaluated over a 2 year follow up period.

Results

Survival after 2 years was 37% in fracture cases compared with 88% in controls (log rank test 62.6, df = 1, p = 0.0001). In the first year 45 patients died but only one control. By 2 years 58 patients but only 8 controls had died. Patients with hip fracture died from various causes, the most common being bronchopneumonia (21 cases), heart failure (9 cases), and ischaemic heart disease (8 cases). Factors associated with increased mortality after hip fracture included older age, residence before fracture in a nursing or residential home, presence of comorbid diseases, and poor functional activity before fracture. Patients with fracture were often disabled with poor quality of life. By 24 months 7 patients could not walk, 12 required residential accommodation, and the mean SF‐36 physical summary score was 1.7SD below the normal standards.

Conclusions

Low trauma hip fracture in men is associated with a significant increase in mortality and morbidity. Impaired function before fracture is a key determinant of mortality after fracture.

Keywords: disease outcomes, hip fracture, men, mortality, osteoporosis

Hip fracture is the major adverse clinical and public health consequence associated with osteoporosis. As populations are aging the incidence of hip fractures is increasing.1 The lifetime risk for sustaining hip fracture is estimated at 18% in women and 6% in men.2 Most research on risk factors and outcomes in hip fracture have been undertaken in women. Substantially less information is available for men, although a large number of factors have been suggested to influence male osteoporosis and hip fracture.3,4

In this study we aimed at characterising mortality, morbidity, and impairment in health related quality of life of men with low trauma hip fracture. We also looked at various predictors of mortality, including functional status and levels of residential care. We studied a consecutive series of men with hip fracture who were followed up prospectively for 2 years.

Patients and methods

Study design

A prospective case‐control study of male hip fractures was undertaken at the Royal Cornwall Hospital, the only referral centre for orthopaedic trauma in Cornwall. It had no upper age limit, patients and controls came from a well defined geographical area with a homogeneous, stable population, and one single observer made all the clinical observations. Subjects were recruited over a 14 month period to avoid seasonal bias. No subjects dropped out after consent and 100% of survivors were followed up. The study was approved by the local research ethics committee and informed written consent obtained.

Patients

Over 14 consecutive months (in 1995–97), 100 men aged ⩾50 years admitted consecutively to the Royal Cornwall Hospital with a low trauma hip fracture were studied. “Low trauma” was defined as falls from standing height or less. Patients with hip fractures after major trauma, patients not resident in Cornwall, and patients with active malignancy were excluded. Fracture cases were identified by daily review of inpatient admissions to the orthopaedic wards and medical admissions unit: 51 fractures involved the right hip, 48 the left with one bilateral; 55 affected the femoral neck, and 45 were intertrochanteric.

Controls

Simultaneously, “controls” were recruited from a local general practitioner register, comprising men aged ⩾50 years with no history of hip fracture. Subjects with other fractures were not excluded. When a “patient” was identified, an age matched control subject was invited in parallel to participate from a list of 2088 eligible men. If they refused, the next nearest age matched person was invited until a consenting participant was recruited; 185 people were approached to recruit 100 controls. The overall response rate (54%) fell with age (100% for those aged 50–60 years; 50% for those aged over 70 years); reduced response rate from elderly controls made age matching incomplete.

Study protocol

General assessment

Details were recorded of age, residence (own home, other's home, residential home, nursing home), comorbid conditions (dementia, Parkinson's disease, heart disease, arthritis, diabetes mellitus, stroke, gastrointestinal disorders), and functional ability measured using the Mediterranean Osteoporosis (MEDOS) Study questionnaire,5 which identifies risk factors 4 weeks before assessment.

Physical examination

Initial standardised clinical assessments of cases and controls included history and examination. Height and weight were recorded in 97 controls and 74 and 85 fracture cases, respectively, with missing observations due to frailty and comorbidities.

Risk factor questionnaires

Interviewer assisted questionnaires at entry collected personal details, mental score, concomitant diseases, drugs, and (for cases) details of the fracture and surrounding circumstances.

Health related quality of life

Health related quality of life was measured with the Short Form‐36 (SF‐36). Ill health, hearing, visual impairments, poor mental status, and comorbidities made it impossible to collect all data; missing data were obtained where possible from the next of kin or carer.

Bone mineral density (BMD) measurement

Bone mineral density was measured at the lumbar spine and proximal femur by dual energy x ray absorptiometry using Hologic QDR 1000 in cases within 1 week of fracture and in controls at their first visit.6

Follow up

Survivors were reviewed at 6, 12, and 24 months, recording the eight point functional ability questionnaire and SF‐36. Vital status and information about current residence was assessed by direct contact with the patient, relative, or carer at 12 and 24 months. Cause of death was obtained from death certificates and postmortem reports.

Statistical analysis

General

Data were analysed using SPSS version 7.5.1 and STATA version 4.0. Descriptive statistics described the frequency of adverse health factors in those with and without hip fracture. For categorical variables, percentages were calculated and significance estimated using Pearson χ2 tests. Odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals were calculated using STATA.

Adjustments

A reduced response rate in elderly controls compromised age matching and consequently all comparisons were age adjusted; additional adjustments were made for other variables, where applicable: BMD was adjusted for age, height, and weight; mortality was adjusted for age and body mass index (BMI).

Mortality

Survival was assessed using Kaplan‐Meier curves. A Cox proportional hazards model was used to determine factors linked with increased mortality. To explore the impact on mortality of the comorbid factors we derived a new variable comprising the number of new factors affected.

Results

Subjects were followed up for a mean of 661 days (1.8 years) (range 2–1128 days). Follow up was 100% in both groups. Overall, after 24 months follow up, 58 of the patients with fracture had died, 12 were in institutional care (8 in hospital/nursing home and 4 in residential homes) and 30 were in their own homes. By contrast, eight of the controls had died, 4 were in institutional care (2 in hospital/nursing home and 2 in residential care), and 88 were in their own homes.

Social circumstances

Immediately before admission 71 of the patients with fracture were living in their own or in another's home, 14 were in a residential home, and 15 in a nursing home (table 1).

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of cases and controls.

| Baseline characteristics | No | Cases | No | Controls | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 100 | 79.9 (9.4) | 100 | 75.1 (9.6) | <0.001 |

| Residence (n) | 100 | 100 | |||

| Own home | 71 | 96 | χ2 = 22.7, df = 2, p<0.000 | ||

| Residential home | 14 | 2 | |||

| Nursing home | 15 | 2 | |||

| Comorbidity, No (%) | 96 | 94 | |||

| None | 17 (18) | 40 (43) | χ2 = 22.4, df = 2, p<0.001 | ||

| <3 | 32 (33) | 36 (38) | |||

| ⩾3 | 47 (49) | 18 (19) | |||

| Physical component score, mean (SD) | |||||

| Baseline | 81 | 38.9 (11.8) | 100 | 46 (10) | <0.001 |

| Health assessment score, mean (SD) | |||||

| Baseline | 91 | 0.83 (0.85) | 99 | 0.27 (0.51) | <0.001 |

| Mental component score, mean (SD) | |||||

| Baseline | 81 | 50.1 (12.6) | 100 | 56.6 (8.1) | <0.001 |

General health

Patients with fracture weighed less (mean (SD) 67.8 (11.2) kg) than controls (77.7 (16.3) kg) and had a lower mean BMI (cases 23.4 (3.3) kg/m3; controls 26.7 (5.5) kg/m3). There was no difference in height. Mini‐mental score examination differed in cases (within 48 hours of fracture) and controls (at first visit); 48 cases and 84 controls scored 10; 15 cases and 3 controls scored ⩽5. Mental status could not be assessed in nine cases with dementia.

Comorbid conditions

Comorbidities were identified in 79 cases and 54 controls (χ2 = 13.8; df = 1, p<0.001); 47 cases had two or more comorbid conditions compared with 18 controls (χ2 = 29.7, df = 7, p<0.0001) (table 1). Poor vision, Parkinson's disease, dementia, reduced mobility, and a history of falls were more commen in cases. No patients were receiving oral steroids in the 12 months before their fracture; there were no differences between cases and controls in the frequency of intake of any drugs that might be linked to developing osteoporosis.

Bone mineral density

Cases had significantly lower BMD at all sites than controls. T scores <−2.5 at the femoral neck were present in 48/58 (83%) fracture cases who had a scan compared with 39/100 (39%) controls. After adjusting for age, height, and weight, the risk of hip fracture was substantial per 0.1 mg/cm2 decrease in bone mass: for the lumbar spine odds ratio (OR) = 1.2 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.0 to 1.6); for the femoral neck OR = 2.0 (95% CI 1.3 to 3.1). These BMD findings have been reported previously.6

Morbidity

Residential status

Twelve months after fracture 55 patients were still alive; 35 were at home, and 20 in residential accommodation (6 in residential homes; 14 in nursing homes). All 35 patients at home 12 months after fracture had been living at home before fracture; 8 patients who had been at home before fracture were in residential care. The situation was similar 24 months after fracture, with 30 of the 42 surviving cases still at home. Most controls (93 and 88, respectively) continued to live in their own homes at 12 and 24 months.

Functional status

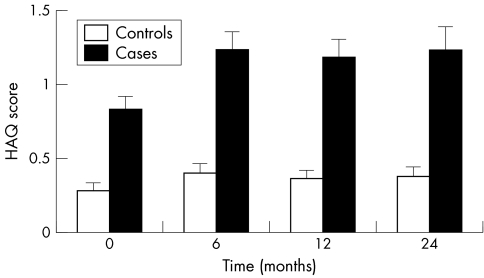

Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) scores were available for 91, 50, 47, and 35 patients and for 99, 97, 87, and 84 controls at baseline, 6, 12, and 24 months, respectively. The mean HAQ score in the hip fracture cases was 0.84 at baseline, and this rose to 1.2 in the 50 survivors at 6 months and stabilised at 1.2 in the fracture survivors at 12 and 24 months. In controls the mean HAQ score at first visit was 0.27 and increased slightly to 0.39 at 24 months (fig 1).

Figure 1 Change in health using the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) over 24 months.

Mobility

Details of mobility 12 months after fracture were available in 47 cases: 17 (36%) could walk independently; 7 (15%) could not walk. Data from 87 controls showed that 73 (84%) walked normally and only 1 (1%) could not walk. Details at 24 months after fracture were available from 35 cases: 12 (34%) could walk independently; 7 (20%) could not walk. Data from 84 controls showed 71 (85%) walked normally; none were unable to walk.

Health related quality of life

Eighty one patients completed the SF‐36 questionnaire within 48 hours of their fracture. Follow up scores at 6, 12, and 24 months were available for 51, 47, and 34 cases respectively. All controls completed the SF‐36 questionnaire at baseline and 97, 87, and 84 controls at 6, 12, and 24 months, respectively. Baseline SF‐36 scores in the cases, reflecting health status before fracture, were significantly worse than in controls for all domains except pain.

Composite physical and mental component scores showed that cases before fracture had worse overall health than controls. Mean physical scores before fracture in cases were more than 1SD below the standard US means. Mental scores before fracture, although less than in controls, were not abnormal by US standards. The immediate effect of fracture was seen on the physical but not on the mental component summary scores; after fracture, physical scores deteriorated steadily to more than 1.7SD below the US mean at 2 years. The fracture did not have an immediate effect on the mental scores, though 2 years after fracture there had been a significant decline in mental component scores (p<0.04).

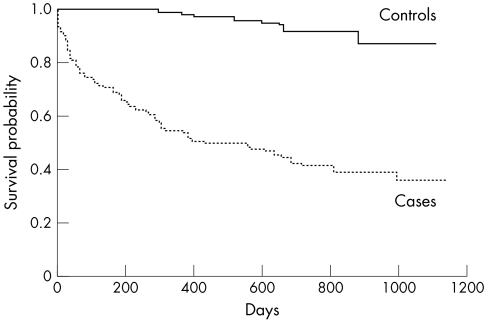

Mortality

Fifty eight patients with hip fracture died; early mortality (at 90 days) was 25%. More deaths occurred in the first (45) than the second year (13). Twelve survivors at 2 years were in care and 30 in their own home. At 2 years only 8 controls had died, 4 were in hospital, nursing home, or residential home and 88 were in their own home. The Kaplan‐Meier survival curves (fig 2) illustrate the excess of deaths in fracture cases compared with controls. This difference was most marked in the first 3 months after fracture. Overall survival among the cases was 37% compared with 88% in controls (log rank test 62.6, df = 1, p = 0.0001). In the first year of observation 45 patients died but only one of the controls. By the end of follow up 60 patients but only 10 controls had died. Patients with hip fracture died from various causes (table 2), including bronchopneumonia (21 cases), heart failure (9 cases), and ischaemic heart disease (8 cases). There was no evidence that bronchopneumonia or heart failure occurred at different times after fracture. Of 21 deaths due to bronchopneumonia, six occurred by 1 month, nine between 1 and 6 months, and six after 6 months.

Figure 2 Kaplan‐Meier survival curves among cases and controls. Overall survival among the cases was 37% compared with 88% in controls (log rank test 62.6, df = 1, p = 0.0001).

Table 2 Causes of death among cases and controls.

| Cause of death | Cases | Controls |

|---|---|---|

| (n = 60) | (n = 10) | |

| Bronchopneumonia | 21 | 4 |

| Heart failure | 9 | 0 |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 8 | 1 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 2 | 0 |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 4 | 0 |

| Malignancy | 5* | 1 |

| Old age/dementia | 2 | 1 |

| Infections | 4† | 0 |

| Others | 5‡ | 3§ |

*Prostate (three), stomach (one), unknown (one); †septicaemia after gangrene heel (one), gastrointestinal (GI) obstruction (one), gastric ulcer (one), pseudomembranous colitis (one); ‡small bowel ischaemia (two), GI bleed (one), Parkinson's disease (one), carbon monoxide poisoning (one); §respiratory arrest due to chronic obstructive airways disease (one), spinal cord compression (one), ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm (one).

Age greatly influenced mortality (log rank 24.8, df = 1, p = 0.0001). Survival was 100% when the hip fracture occurred in the 5th decade, only 50% in the 7th decade, and all but one patient aged > 90 years died.

Predictors of mortality

Overall predictors

Cox regression analysis (table 3) confirmed that mortality was significantly higher in hip fracture cases than in controls (hazards ratio (HR) = 9.3 (95% CI 4.8 to 16.3); p<0.0001). This excess mortality persisted after adjusting for age (HR (95% CI) 8.1 (4.1 to 16.0)) and body mass index (HR (95% CI) 7.8 (3.6 to 16.9)) After controlling for quality of life before fracture using the physical component domain of the SF‐36 or HAQ scores, fracture cases continued to show a six‐ to sevenfold excess mortality compared with controls (HR = 6.2–7.2). There were insufficient deaths by specific causes to examine reliably whether differences in status before fracture predicted specific types of death.

Table 3 Influence of hip fracture on mortality: cases versus controls.

| Hazards ratio | p Value | |

|---|---|---|

| (95% CI) | ||

| Presence of hip fracture | 9.3 (4.8 to 16.3) | 0.0001 |

| Adjusted for age | 8.1 (4.1 to 16.0) | 0.0001 |

| Adjusted for age and BMI | 7.8 (3.6 to 16.9) | 0.0001 |

| Adjusted for age and baseline functional capacity* | 6.7 (3.4 to 13.4) | 0.0001 |

| Adjusted for age and baseline physical component score† | 6.2 (3.1 to 12.4) | 0.0001 |

| Adjusted for age and baseline mental component score† | 7.2 (3.5 to 14.7) | 0.0001 |

BMI, body mass index.

*Health Assessment Score; *SF‐36.

Residence, comorbidity, and physical function

After adjusting for age using Cox regression analysis only institutional care at the time of hip fracture, the presence of a comorbidity, and poor physical function before fracture were significant predictors of mortality (table 4). The presence of one or more comorbid diseases at the time of fracture more than doubled the risk of dying (HR = 2.8). Mortality exceeded 70% when another disease was present but was <40% in the absence of a concomitant disease.

Table 4 Influence of baseline characteristics on mortality after hip fracture.

| Baseline characteristics | Hazards ratio | Hazards ratio* | Significance† |

|---|---|---|---|

| (95% CI) | (95% CI) | ||

| Age (for each year increase in age) | 1.1 (1.0 to 1.1) | – | 0.000 |

| Age (>70 years) | 5.8 (1.8 to 18.4) | – | 0.003 |

| Body mass index (per kg/m2) | 0.98 (0.89 to 1.1) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.1) | NS |

| Marital status: single v married | 1.3 (0.8 to 2.1) | 1.2 (0.7 to 1.9) | NS |

| Presence of one or more comorbidity | 4.2 (1.5 to 11.7)‡ | 2.8 (1.0 to 7.7) | 0.05 |

| Fracture type: cervical v trochanteric | 1.3 (0.8 to 2.2) | 1.1 (0.7 to 1.9) | NS |

| Mental score: <8.0 v ⩾8 | 1.8 (1.0 to 3.2)§ | 1.5 (0.9 to 2.6) | NS |

| Residence: residential v own home | 2.1 (1.1 to 4.1)¶ | 1.7 (0.8 to 3.3) | NS |

| Residence: nursing v own home | 2.0 (1.1 to 3.9) | 2.1 (1.1 to 4.0) | 0.03 |

| Physical component score (per unit change) | 0.95 (0.93 to 0.98) | 0.95 (0.93 to 0.98) | 0.002 |

| Functional capacity (per unit change in HAQ) | 1.5 (1.1 to 2.1) | 1.6 (1.2 to 2.1) | 0.004 |

| Mental component score (per unit change) | 1.0 (0.98 to 1.0) | 1.0 (0.98 to 1.0) | NS |

*After adjusting for age; †both unadjusted and after adjusting for age; ‡p<0.005; §p<0.04; ¶p<0.03.

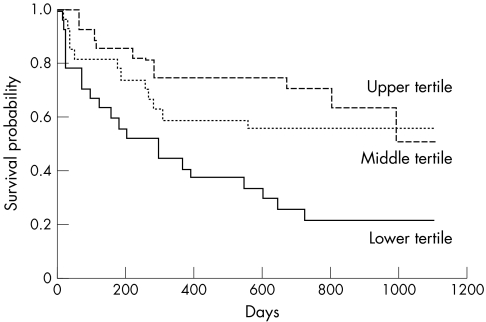

The initial physical component score from the SF‐36, available in 81 cases, was a highly significant predictor of mortality (log rank test 11.6, df = 2, p = 0.003): 21 (78%) cases in the lowest tertile had died by 2 years compared with 12 (44%) in the middle and 10 (37%) in the highest tertiles. Patients in the lowest tertile for physical component scores had high immediate mortality after fracture; only 21 (78%) surviving for 1 month and 6 (22%) for 2 years. No patients in the highest tertile died in the first 2 months after fracture; their 2 year survival was 70% (fig 3).

Figure 3 Kaplan‐Meier survival curves for cases stratified by initial physical component score of the SF‐36.

Stepwise multiple regression with age, functional capacity, and residence in the equation showed that age and functional capacity were good predictors of excess mortality, with hazards ratios of 1.1 and 1.5, respectively. After adding comorbidity to the regression equation, the only significant variable influencing mortality was age. On substituting a cut off point of 70 years for age into the regression equation, the significance of age on mortality was more apparent (HR = 4.6, 95% CI 1.4 to 15.0; p<0.01). In this analysis baseline functional capacity no longer retained significance (HR = 1.3, 95% CI 0.9 to 1.8, p = NS). Repeat analysis replacing functional capacity (HAQ) with the physical component score did not alter the results. Age and baseline physical component score were the only variables that significantly influenced mortality; age was dominant.

Discussion

We found a six‐ to sevenfold increased risk of death in male hip fracture cases compared with population controls. Such excess mortality,7 which is particularly high in men,8 has been well described. Thirty four observational studies have reported mortality data in male hip fractures9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42; with few exceptions,12,25 most found that men had higher mortalities, including evaluations of mortality compared with age and sex matched controls10 and deaths in the general population.12 Mortality rates varied from 11%9 to 71%,20 with in‐hospital mortality between 2%12 and 37%.15 Such differences reflect variations in case selection and characteristics of the populations studied. The risk of death is greatest immediately after the fracture and decreases over time,7 with few deaths directly attributed to the hip fracture and most reflecting the chronic illnesses predisposing towards fracture.

Our data reflect these views: 45/60 deaths in our cases occurred during the first year after fracture; 38 were caused by pneumonia and heart disease. Although male hip fracture is a pre‐terminal event in some cases, there is good evidence that it also shortens life; Trombetti and colleagues calculated that after hip fracture male life expectancy is reduced by an average of 5.8 years.32 We found no deaths due to pulmonary thromboembolic disease; the local hospital policy, which used heparin to anticoagulate hip fracture cases, appears effective.

Most fracture survivors in our study had reduced function, poor quality of life, and increased dependency. An important impairment was inability to walk: 12 months after fracture only 17/47 (36%) of our patients walked independently; and at 24 months only 12/35 (34%) patients. We assessed function with the MEDOS questionnaire; we do not believe using a form developed in southern Europe was inappropriate in Cornwall. Our findings are slightly worse than walking ability after fracture reported in mixed sex series. For example, one early retrospective analysis of 360 patients with hip fractures reported that 22% were non‐ambulatory 12 months after fracture,43 and a recent retrospective study of 280 patients with hip fractures in Singapore44 found that 28% of those alive at 1 year could walk without aids.

The SF‐36 showed that before fracture our cases had significantly worse overall health than controls; mean physical component SF‐36 scores were more than 1SD below standard US mean levels. As we could not assess the SF‐36 in some of our fracture cases, and these patients had very poor health, excluding them will have enhanced the apparent health status of the fracture group as a whole. After fracture physical scores deteriorated steadily to more than 1.7SD below the US mean levels at 2 years. There was an associated decline in SF‐36 mental component scores. Comparable findings with the SF‐36 have been reported in several studies of male and female hip fracture cases,45,46,47 including the low baseline quality of life scores.48 The need for long term care shows the extent of dependency; in our cases 12 survivors required residential accommodation after 24 months. The high frequency of institutionalisation after fracture has been well described. Diamond and colleagues reported that 50% of men were institutionalised 12 months after fracture,24 though other series of men and women report slightly lower rates of institutionalisation,49 with large differences between centres.50 There is some evidence that management approaches, like care pathways, reduce the number of cases who become institutionalised.51

The strong points of our study include evaluating consecutive men with hip fracture from a single area of the UK, with prospectively collected complete follow up data. One limitation was incomplete response rates for participation in the control group, which reduced with increasing age, making our controls younger than fracture cases. Although adjustments were made when analysing mortality, if potential controls who declined to participate had poorer health, the excess mortality and poor outcomes of fracture cases might have been overestimated. A second limitation was that status before fracture was defined after fracture, when recall might have been impaired, with resultant misclassification. Finally, Cornwall is a rural area and evidence shows that hip fracture rates are lower in rural communities52; our findings may therefore not be completely generalisable.

In conclusion, we have shown that low trauma hip fracture in men results in a significant increase in mortality and morbidity. After 24 months, of 100 fracture cases, 58 were dead, 12 were in institutional care, and only 30 remained in their own homes. Age and impaired function before fracture were key determinants of mortality after fracture.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge support to the Royal Cornwall Hospital from the UK National Health Service (NHS) Research and Development Programme. We are also grateful to the ARC (http://www.arc.org.uk; accessed 27 September 2005) for supporting research activities in our units.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interests.

References

- 1.Cummings S R, Melton L J. Epidemiology and outcomes of osteoporotic fractures. Lancet 20023591761–1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Melton L J, 3rd, Therneau T M, Larson D R. ong‐term trends in hip fracture prevalence: the influence of hip fracture incidence and survival. Osteoporos Int 1998868–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pande I, Francis R M. Osteoporosis in men. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 200115415–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaufman J M, Johnell O, Abadie E, Adami S, Audran M, Avouac B.et al Background for studies on the treatment of male osteoporosis: state of the art. Ann Rheum Dis 200059765–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dequeker J, Ranstam J, Valsson J, Sigurgevisson B, Allander E. The Mediterranean Osteoporosis (MEDOS) Study questionnaire. Clin Rheumatol 19911054–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pande I, O'Neill T W, Pritchard C, Scott D L, Woolf A D. Bone mineral density, hip axis length and risk of hip fracture in men: results from the Cornwall Hip Fracture Study. Osteoporos Int 200011866–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cummings S R, Melton L J. Epidemiology and outcomes of osteoporotic fractures. Lancet 20023591761–1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kanis J A, Johnell O, Oden A, De Laet C, Mellstrom D. Diagnosis of osteoporosis and fracture threshold in men. Calcif Tissue Int 200169218–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beals R K. Survival following hip fracture. Long follow‐up of 607 patients. J Chronic Dis 197225235–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colbert D S, O'Muircheartaigh I. Mortality after hip fracture and assessment of some contributory factors. Ir J Med Sci 197614544–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jensen J S, Tondevold E. Mortality after hip fractures. Acta Orthop Scand 197950161–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ceder L, Thorngren K G, Wallden B. Prognostic indicators and early home rehabilitation in elderly patients with hip fractures. Clin Orthop 1980152173–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jensen J S. Determining factors for the mortality following hip fractures. Injury 198415411–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Magaziner J, Simonsick E M, Kashner T M, Hebel J R, Kenzora J E. Predictors of functional recovery one year following hospital discharge for hip fracture: a prospective study. J Gerontol 199045M101–M107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Myers A H, Robinson E G, Van Natta M L, Michelson J D, Collins K, Baker S P. Hip fractures among the elderly: factors associated with in‐hospital mortality. Am J Epidemiol 19911341128–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fisher E S, Baron J A, Malenka D J, Barrett J A, Kniffin W D, Whaley F S.et al Hip fracture incidence and mortality in New England. Epidemiology 19912116–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thorngren K G, Ceder L, Svensson K. Predicting results of rehabilitation after hip fracture. A ten‐year follow‐up study. Clin Orthop 199328776–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sernbo I, Johnell O. Consequences of a hip fracture: a prospective study over 1 year. Osteoporos Int 19933148–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu‐Yao G L, Baron J A, Barrett J A, Fisher E S. Treatment and survival among elderly Americans with hip fractures: a population‐based study. Am J Public Health 1994841287–1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pitto R P. The mortality and social prognosis of hip fractures. A prospective multifactorial study. Int Orthop 199418109–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poor G, Atkinson E J, O'Fallon W M, Melton L J., 3rd eterminants of reduced survival following hip fractures in men. Clin Orthop 1995319260–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poor G, Atkinson E J, Lewallen D G, O'Fallon W M, Melton L J., 3rd ge‐related hip fractures in men: clinical spectrum and short‐term outcomes. Osteoporos Int 19955419–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nettleman M D, Alsip J, Schrader M, Schulte M. Predictors of mortality after acute hip fracture. J Gen Intern Med 199611765–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Diamond T H, Thornley S W, Sekel R, Smerdely P. Hip fracture in elderly men: prognostic factors and outcomes. Med J Aust 1997167412–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aharonoff G B, Koval K J, Skovron M L, Zuckerman J D. Hip fractures in the elderly: predictors of one year mortality. J Orthop Trauma 199711162–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stavrou Z P, Erginousakis D A, Loizides A A, Tzevelekos S A, Papagiannakos K J. Mortality and rehabilitation following hip fracture. A study of 202 elderly patients. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl 199727589–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wolinsky F D, Fitzgerald J F, Stump T E. The effect of hip fracture on mortality, hospitalization, and functional status: a prospective study. Am J Public Health 199787398–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Forsen L, Sogaard A J, Meyer H E, Edna T, Kopjar B. Survival after hip fracture: short‐ and long‐term excess mortality according to age and gender. Osteoporos Int 19991073–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Center J R, Nguyen T V, Schneider D, Sambrook P N, Eisman J A. Mortality after all major types of osteoporotic fracture in men and women: an observational study. Lancet 1999353878–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cree M, Soskolne C L, Belseck E, Hornig J, McElhaney J E, Brant R.et al Mortality and institutionalization following hip fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc 200048283–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chariyalertsak S, Suriyawongpisal P, Thakkinstain A. Mortality after hip fractures in Thailand. Int Orthop 200125294–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trombetti A, Herrmann F, Hoffmeyer P, Schurch M A, Bonjour J P, Rizzoli R. Survival and potential years of life lost after hip fracture in men and age‐matched women. Osteoporos Int 200213731–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fransen M, Woodward M, Norton R, Robinson E, Butler M, Campbell A J. Excess mortality or institutionalization after hip fracture: men are at greater risk than women. J Am Geriatr Soc 200250685–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Orces C H, Lee S, Bradshaw B. Sex and ethnic differences in hip fracture‐related mortality in Texas, 1990 through 1998. Tex Med 20029856–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kiebzak G M, Beinart G A, Perser K, Ambrose C G, Siff S J, Heggeness M H. Undertreatment of osteoporosis in men with hip fracture. Arch Intern Med 20021622217–2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lawrence V A, Hilsenbeck S G, Noveck H, Poses R M, Carson J L. Medical complications and outcomes after hip fracture repair. Arch Intern Med 20021622053–2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Der Klift M, Pols H A, Geleijnse J M, Van Der Kuip D A, Hofman A, De Laet C E. Bone mineral density and mortality in elderly men and women: the Rotterdam Study. Bone 200230643–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Olsson C, Petersson C, Nordquist A. Increased mortality after fracture of the surgical neck of the humerus: a case‐control study of 253 patients with a 12‐year follow‐up. Acta Orthop Scand 200374714–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wehren L E, Hawkes W G, Orwig D L, Hebel J R, Zimmerman S I, Magaziner J. Gender differences in mortality after hip fracture: the role of infection. J Bone Miner Res 2003182231–2237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roberts S E, Goldacre M J. Time trends and demography of mortality after fractured neck of femur in an English population, 1968–98: database study. BMJ 2003327771–775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kanis J A, Oden A, Johnell O, De Laet C, Jonsson B, Oglesby A K. The components of excess mortality after hip fracture. Bone 200332468–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kanis J A, Oden A, Johnell O, De Laet C, Jonsson B. Excess mortality after hospitalisation for vertebral fracture. Osteoporos Int 200415108–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miller C W. Survival and ambulation following hip fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Am 197860930–934. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wong M K, Arjandas, Ching L K, Lim S L, Lo N N. Osteoporotic hip fractures in Singapore—costs and patient's outcome. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2002313–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hall S E, Williams J A, Senior J A, Goldswain P R, Criddle R A. Hip fracture outcomes: quality of life and functional status in older adults living in the community. Aust N Z J Med 200030327–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Adachi J D, Loannidis G, Berger C, Joseph L, Papaioannou A, Pickard L.et al The influence of osteoporotic fractures on health‐related quality of life in community‐dwelling men and women across Canada. Osteoporos Int 200112903–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Peterson M G, Allegrante J P, Cornell C N, MacKenzie C R, Robbins L, Horton R.et al Measuring recovery after a hip fracture using the SF‐36 and Cummings scales. Osteoporos Int 200213296–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Randell A G, Nguyen T V, Bhalerao N, Silverman S L, Sambrook P N, Eisman J A. Deterioration in quality of life following hip fracture: a prospective study. Osteoporos Int 200011460–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cumming R G, Klineberg R, Katelaris A. Cohort study of risk of institutionalisation after hip fracture. Aust N Z J Public Health 199620579–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Parker M J, Lewis S J, Mountain J, Christie J, Currie C T. Hip fracture rehabilitation—a comparison of two centres. Injury 2002337–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.March L M, Cameron I D, Cumming R G, Chamberlain A C, Schwarz J M, Brnabic A J.et al Mortality and morbidity after hip fracture: can evidence based clinical pathways make a difference? J Rheumatol 2000272227–2231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sanders K M, Nicholson G C, Ugoni A M, Seeman E, Pasco J A, Kotowicz M A. Fracture rates lower in rural than urban communities: the Geelong Osteoporosis Study. J Epidemiol Community Health 200256466–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]