Abstract

Objective

To assess available management strategies in ankylosing spondylitis (AS) using a systematic approach, as a part of the development of evidence based recommendations for the management of AS.

Methods

A systematic search of Medline, Embase, CINAHL, PEDro, and the Cochrane Library was performed to identify relevant interventions for the management of AS. Evidence for each intervention was categorised by study type, and outcome data for efficacy, adverse effects, and cost effectiveness were abstracted. The effect size, rate ratio, number needed to treat, and incremental cost effectiveness ratio were calculated for each intervention where possible. Results from randomised controlled trials were pooled where appropriate.

Results

Both pharmacological and non‐pharmacological interventions considered to be of interest to clinicians involved in the management of AS were identified. Good evidence (level Ib) exists supporting the use of non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and coxibs for symptomatic treatment. Non‐pharmacological treatments are also supported for maintaining function in AS. The use of conventional antirheumatoid arthritis drugs is not well supported by high level research evidence. Tumour necrosis factor inhibitors (infliximab and etanercept) have level Ib evidence supporting large treatment effects for spinal pain and function in AS over at least 6 months. Level IV evidence supports surgical interventions in specific patients.

Conclusion

This extensive literature review forms the evidence base considered in the development of the new ASAS/EULAR recommendations for the management of AS.

Keywords: ankylosing spondylitis, evidence based medicine, systematic review

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is a chronic inflammatory rheumatic disease most commonly affecting the axial skeleton, which historically has been difficult to treat. Recent years have seen the introduction of exciting new therapeutic strategies, particularly the tumour necrosis factor inhibitors. Therefore it is important that clinicians are aware of the relative benefits and risks of the different treatments available to them, and have evidence based information about which strategies are the most efficacious in particular patient settings.

The ASsessment in AS (ASAS) International Working Group, in collaboration with the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR), recently developed evidence based recommendations for the management of AS1 to assist all health professionals involved in the care of patients with AS.

The recommendations were developed using information from two major sources: a systematic review of the literature, and expert opinion based on the research evidence and clinical expertise.1 This review details the literature search performed and the results presented to the expert committee for the purpose of developing recommendations for the management of AS.

Methods

A systematic search of the literature published between January 1966 and December 2004 was undertaken using Medline, Embase, CINHAL, PEDro, and Cochrane Library databases. The search included both a general search and an intervention‐specific search. The general search strategy consisted of two basic components: AS in whatever possible terms in the databases (Appendix 1) and types of research in the form of systematic review/meta‐analysis, randomised controlled trial (RCT)/controlled trial, uncontrolled trial, cohort study, case‐control study, cross sectional study, and economic evaluation (Appendix 2). The general search aimed at summarising the current available treatments from the literature for AS. The summary results of this search were reported to the ASAS/EULAR expert committee at the beginning of the recommendation development process.

After the expert group had generated 10 recommendation propositions, an intervention‐specific search was undertaken to identify evidence for each specific treatment. The search strategy included the terms for AS (Appendix 1) and any possible terms for the specific intervention. The results of the two searches were then combined and duplications excluded. Medical subject heading (MeSH) search was used for all databases and keyword search was used if the MeSH search was not available. All MeSH search terms were exploded. The reference lists of reviews or systematic reviews were examined and any additional studies meeting the inclusion/exclusion criteria were included.

The search in the Cochrane Library included a MeSH search of the Cochrane reviews, abstracts of Quality Assessed Systematic Reviews, the Cochrane Controlled Trial Register, NHS Economic Evaluation Databases, Health Technology Assessment Database, and NHS Economic Evaluation Bibliography Details Only. Abstracts of scientific meetings held in 2003 and 2004 and “online first” publications were also hand searched for relevant studies.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Only studies with clinical outcomes for AS were included. The main focus of interest was on systematic reviews, RCTs/controlled trials, uncontrolled trials/cohort studies, case‐control studies, cross sectional studies, and economic evaluations. Studies that included patients with AS in a larger cohort of different spondyloarthritides (for example, psoriatic arthritis) were excluded unless the results for patients with AS were reported separately. Studies of other seronegative spondyloarthritides or other inflammatory joint conditions, animal studies, non‐clinical outcome studies, narrative review articles, commentaries, and guidelines were also excluded.

Categorising evidence

Evidence was categorised according to study design using a hierarchy of evidence in descending order according to qualities2 (table 1), and the highest level of available evidence for each intervention was reviewed in detail. When very few high level studies were available, the next highest category was also reviewed. The most recent meta‐analysis of RCTs (level Ia) was reviewed for each intervention, and any RCTs published since the meta‐analysis was conducted were also considered.

Table 1 Evidence hierarchy and traditional strength of recommendation.

| Category of evidence | Strength of recommendation |

|---|---|

| Ia Meta‐analysis of randomised controlled trials | A Category I evidence |

| Ib Randomised controlled trial | |

| IIa Controlled study without randomisation | B Category II evidence or extrapolated from category I evidence |

| IIb Quasi‐experimental study | |

| III Non‐experimental descriptive studies, such as comparative, correlation, and case‐control studies | C Category III evidence or extrapolated from category I or II evidence |

| IV Expert committee reports or opinion or clinical experience of respected authorities, or both | D Category IV evidence or extrapolated from category II or III evidence |

Efficacy was assessed specifically for AS, and toxicity data were evaluated specifically for the intervention, irrespective of the musculoskeletal condition.

Estimation of effectiveness and cost effectiveness

Effect size (ES, mean change divided by the standard deviation of the change) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) compared with placebo or active control were calculated for two predetermined continuous outcomes: pain relief and improvement in function.3 The percentage of patients with an ASAS20 response to treatment, or with moderate to excellent (predefined as more than 50%) pain relief or moderate functional improvement (predefined as more than 20%) was calculated where possible, and the number needed to treat (NNT) was estimated for these dichotomous outcomes.4 The NNT is the number of patients who need to be treated with a given intervention in order to prevent one poor outcome, and is the inverse of the absolute risk reduction. Results from the latest systematic review were used if there was more than one systematic review for the same intervention. Statistical pooling was undertaken as appropriate5 when a systematic review was not available, or when more recent RCTs could be included. The NNT and 95% CI were reported only if statistically significant; otherwise “NS” (not significant) was used to avoid difficulty in interpreting the results.6 Relative risk (RR) was calculated for adverse effects.

When economic evaluation was available, study design, comparator, perspective, time horizon, discounting, total costs, and effectiveness were reviewed. The incremental cost effectiveness ratio was calculated. Quality of life years were used when available, otherwise disease‐specific outcomes such as pain relief and functional improvement were used.

Data were extracted by one investigator (JZ). A customised form was used for the data extraction.

Results

Treatment modalities and types of research evidence

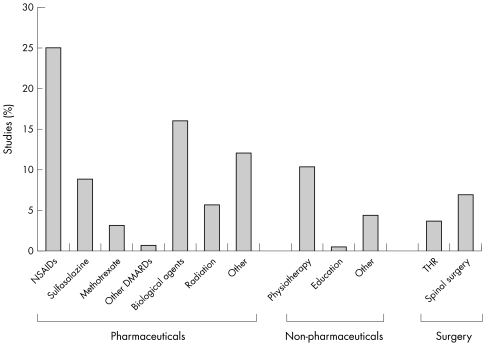

The general search yielded 4100 hits (Medline 2395, Embase 1581, CINAHL 73, PEDro 16, and Cochrane 35). After deleting duplications, non‐treatment studies, and studies of diseases other than AS, 458 hits remained. Of these, 318 were original studies and 140 were narrative reviews, commentaries, or editorials. Figure 1 shows the breakdown of interventions among the original 318 studies. Of these studies, 35 were RCTs, 7 were systematic reviews, and 4 were economic evaluations.

Figure 1 Interventions for AS from the general literature search.

The results from the intervention‐specific search were merged with the results from the general search. After deleting the duplications and articles irrelevant to the questions (for example, studies on radiation therapy), 317 studies remained for review. These included: 73 related to non‐pharmacological treatments; 55 associated with NSAIDs or coxibs; 61 in relation to conventional anti‐rheumatoid arthritis drugs; 8 for bisphosphonate treatment; 6 for thalidomide; 15 for corticosteroids (intravenous or intra‐articular); 64 for biological treatments; and 55 relevant to total hip replacement or spinal surgery.

The evidence for each intervention relevant to the ASAS/EULAR recommendations, as presented to the expert group, is discussed below.

Non‐pharmacological treatment

Physiotherapy and exercise

The effect of physiotherapy has recently been reviewed in a Cochrane systematic review7 summarising the findings of six randomised or quasi‐randomised trials. Of the studies included, Kraag et al reported that an individual programme of therapeutic exercise combined with education and disease information significantly improved function at 4 months (ES 1.14, 95% CI 0.55 to 1.73) compared with no intervention.8 There was no significant effect on pain levels. After the 4 month trial, this improvement in function was maintained by minimal continuing treatment (1.5 mean visits from the physiotherapist between month 4 and month 8).9

Hidding et al compared group physical therapy and home exercises with home exercises alone, after an intensive training programme for both groups, and found that although pain and functioning improved significantly in both intervention groups, there was no significant difference between the groups for these two outcome measures.10 Patient global assessment of improvement and spinal mobility were seen to be statistically higher in the group physiotherapy arm (p<0.05). Cost effectiveness analysis of these patients11 showed that each centimetre of visual analogue scale improvement cost $292 over 1 year.

A third study compared intensive inpatient physiotherapy, hydrotherapy with home exercises, and home exercise alone, but did not specify pain or function as separate outcome variables.12 This study showed significant short term improvement in composite pain and stiffness in the inpatient treatment group at 6 weeks, but there was no difference between the three groups at 6 months. Comparison of an intensive group exercise programme with unsupervised home exercise13 found that neither pain nor function was significantly better in the group physiotherapy arm than in the home exercise arm. A home based exercise and education package was not shown to improve pain or function compared with controls over 6 months.14 However, a recent small RCT of home exercise not included in the Cochrane review showed significant improvements after 8 weeks in both pain (ES 1.99, 95% CI 1.30 to 2.67) and function (ES 0.80, 95% CI 0.23 to 1.38) in young patients with AS (mean age 28 years) who had previously been sedentary.15 It was not possible to pool the results of separate studies owing to differing interventions and outcome measures. The literature suggests that different types of exercise based intervention can impact on disease outcomes in AS, which might account for the lack of significant differences between treatment arms in the absence of a placebo/no treatment arm.

Specific physiotherapy interventions have been less well studied in AS. One randomised controlled trial comparing transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) with sham TENS treatment over 3 weeks reported a significant short term improvement in pain in the treatment arm16; however, when the data were reanalysed the ES of 0.92 did not reach statistical significance (95% CI −0.01 to 1.86, p = 0.05). Passive stretching has been shown in a controlled study to improve range of movement at the hip,17 but pain and function were not assessed. Pulsed magnetic fields may have an effect on pain, as shown in a small open study of seven patients with AS who were intolerant of non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).18 Level Ib evidence does not support the use of heat or whole‐body cryotherapy.19 A number of open studies (level IV evidence) have shown variable results for spa treatment.20,21,22,23 The only randomised controlled trial identified looked at the effect of a 3 week spa exercise programme followed by weekly group physiotherapy sessions, compared with group physiotherapy alone.24 Function was seen to be significantly improved in the spa groups at 4 and 12 weeks (p<0.01), but the effect of treatment on pain or function was not significantly different between the groups at the end of the 40 week study period. A cost effectiveness analysis of this cohort25 showed an incremental cost effectiveness ratio of €7465 to €18 575 for each quality of life year gained over the trial period.

Education

The effect of isolated education for AS is not clear. There has been one controlled study of self management courses for patients with AS,26 which showed early improvements in functioning in the treatment group after 3 weeks, but failed to show significant improvements in pain or function compared with controls at 6 months. Importantly, education brought considerable improvements in self efficacy and motivation. A small controlled trial of cognitive behavioural therapy targeting relaxation, modifying thoughts and feelings, and scheduling positive activities27 failed to show any significant improvements in pain (ES 0.53, 95% CI −0.07 to 1.13); however, there was a convincing improvement in anxiety (ES 1.11, 95% CI 0.48 to 1.75). Cost analysis of a patient education programme over 12 months suggests that indirect cost savings more than compensate for the costs of the programme through a reduction in work days lost.28 There are no clinical studies of the effect of participation in an AS self help group on disease parameters. Vocational rehabilitation is effective in returning patients with chronic rheumatic diseases to work,29 but studies do not distinguish between diseases.

Lifestyle modification

There is little available evidence to support lifestyle modification in AS. Stopping smoking may be of benefit; three cross sectional studies have shown a poorer functional outcome in patients with AS who smoke,30,31,32 but there have not been any interventional studies to support this observation. A low starch diet was effective in reducing pain in one case study,33 but the only open study available did not report pain or function as outcomes.34 A small case‐control study of dairy restriction in patients with arthritis showed that significantly more patients with SpA than those with RA (p<0.001) reported moderate or good subjective improvement.35

NSAIDs and coxibs

Eight randomised, placebo controlled trials were identified, all of which supported the use of NSAIDs or coxibs for pain in AS.36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43 Pooling of results was possible for four NSAID trials, three of which compared a conventional NSAID with a coxib in addition to the placebo arm.41,42,43 There is thus convincing level Ib evidence that NSAIDs improve spinal pain compared with placebo (ES 1.11, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.26), peripheral joint pain (ES 0.62, 95% CI 0.26 to 0.97, reported in only one study36), and function (ES 0.62, 95% CI 0.47 to 0.76) over a short time period (6 weeks). Coxibs are equally effective, the ES for spinal pain 1.05 (0.88 to 1.22) and for function 0.63 (0.47 to 0.80), also showing moderate to large effects in patients with AS compared with placebo. The effect of coxibs on peripheral arthritis has not been specifically investigated in AS; all studies have excluded patients with active peripheral synovitis. A post hoc analysis of etoricoxib in patients with AS with chronic peripheral arthritis compared with spinal disease alone suggests poorer spinal response rates in patients with arthritis.44 Most RCTs of NSAID treatment in AS compare different NSAID compounds, with no clear indication that any one preparation is more efficacious than the others.45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70

Safety concerns associated with NSAIDs and more recently with coxibs must, however, be considered. The recent EULAR recommendations for the management of hip osteoarthritis71 include an extensive review of the gastrointestinal (GI) toxicity of anti‐inflammatory agents; in short, NSAIDs cause an increased risk of GI bleeding,72,73,74,75,76,77 which is dose dependent,75 and can be reduced with gastroprotective agents such as misoprostol, double doses of H2 blockers, and proton pump inhibitors.78,79,80,81,82 Severe GI toxicity (peptic ulceration and bleeding) has been shown to be lower with coxibs,83 although there remains a considerable risk of GI symptoms including dyspepsia and diarrhoea.

Cardiovascular toxicity with coxibs and NSAIDs has become very topical, and what began initially as a safety signal with rofecoxib has now been seen with other coxib preparations and, most recently, with traditional NSAIDs. The most recent meta‐analysis of RCTs of rofecoxib84 calculated the relative risk for myocardial infarction with rofecoxib as 2.30 (95% CI 1.22 to 4.33) compared with placebo. Analysis of preliminary 3 year data from the Adenomatous Polyposis Prevention with Vioxx (APPROVe) study85 showed an increased risk of serious thromboembolic events, including myocardial infarction or stroke in the rofecoxib treated group after 18 months of chronic dosage (RR 1.92, 95% CI 1.19 to 3.11), and led to the removal of rofecoxib from the market. Preliminary results of one of two long term cancer prevention studies have subsequently shown celecoxib to be associated with a dose related increase in cardiovascular risk compared with placebo,86 and valdecoxib was associated with an increased risk (RR 3.7, 95% CI 1.0 to 13.5) of serious cardiovascular outcome in patients with a coronary artery bypass graft compared with placebo.87 In short, cardiovascular toxicity seems to be a class effect of the coxibs. This may well not be the end of the story, however; concerns were recently raised after preliminary data from the Alzheimer's Disease Anti‐Inflammatory Prevention Trial (ADAPT) suggested a 50% higher risk of myocardial infarction and stroke in naproxen treated patients compared with placebo (unpublished data). The subject of cardiovascular toxicity with traditional NSAIDs is evolving, and continuing research will hopefully clarify the increased risk which may be associated with NSAID use.

Simple analgesics

There is no disease‐specific evidence to support the use of paracetamol or other analgesics in AS. One small cross sectional study using mail‐out questionnaires found that in 15 patients with AS who took both simple analgesics and NSAIDs for their disease, 13 (87%) patients felt that simple analgesics were less effective than NSAIDs,88 but the question has not been assessed in a prospective manner.

Local and systemic corticosteroids

Intra‐articular steroid injections have been shown to be effective for sacroiliitis (level Ib evidence), with a small randomised placebo controlled trial showing an improvement in pain of 1.94 (95% CI 0.53 to 3.35).89 Periarticular corticosteroid injection around the sacroiliac joint has also been shown to be effective,90 responses persisting for at least 8 weeks (p = 0.02). There are no clinical studies on the efficacy of intra‐articular steroid on peripheral arthritis or enthesitis in AS. One observational study of 51 patients with early oligoarthritis (median disease duration 16 weeks) has shown that intra‐articular treatment is effective, improving disease activity as measured by the Health Assessment Questionnaire, swollen joint count, and patient's global pain and disease activity assessments91; however, by the end of the study no patient had been diagnosed with AS (26 remained undifferentiated oligoarthritis). There have been no clinical trials on the use of local corticosteroid injections for the enthesitis of AS.

Intravenous methylprednisolone has been described as useful in recalcitrant cases of severe, active AS (level IV evidence).92,93,94,95 No studies evaluating the effect of oral corticosteroid treatment in AS have been published.

Disease modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs)

Sulfasalazine

Sulfasalazine has inconclusive level Ia evidence for efficacy in AS. The most recent meta‐analysis96 reviewed 12 randomised controlled trials in active AS, and concluded that there is no evidence for a clinically relevant benefit on spinal symptoms or function, but sulfasalazine may have a role in peripheral joint disease associated with spondyloarthritis. When data from the individual trials were pooled, the effect on back pain (ES −2.38, 95% CI −5.78 to 1.03) or physical function (ES 0.20, 95% CI −0.77 to 1.18) with sulfasalazine compared with placebo was not significant. Two studies described combined groups of patients with spondyloarthritis without reporting results in AS separately. Dougados et al found a significant improvement in swollen joint count in patients treated with sulfasalazine (p = 0.002),97 and Clegg et al showed that improvements in patient global assessments were more marked in the subgroup of patients with peripheral joint involvement.98 In the only extended AS trial reviewed,99 patients treated with sulfasalazine over 3 years had significantly fewer episodes of peripheral joint symptoms than those receiving placebo (p<0.05). There is level IV evidence against an effect of sulfasalazine on enthesitis in spondyloarthritis.100 A pilot study of 5‐aminosalicylic acid (thought to be the active moiety in sulfasalazine) in AS showed improvements in investigator global assessment and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, but did not examine pain or function separately.101

Toxicity with sulfasalazine is common (RR for any adverse event 2.37, 95% CI 1.58 to 3.55)—usually gastrointestinal symptoms, mucocutaneous manifestations, hepatic enzyme abnormalities, and haematological abnormalities.

Methotrexate

One systematic review has been published on the use of methotrexate in AS.102 This reviewed two RCTs, one in 51 patients comparing methotrexate 7.5 mg orally a week in combination with naproxen 1000 mg orally daily with naproxen 1000 mg orally daily alone,103 and a second in 30 patients comparing methotrexate 10 mg orally a week with placebo.104 Outcome measures differed substantially between the two studies, and so pooling of results was not possible. The authors concluded that there was no evidence to support the use of methotrexate in AS. Since that publication, there has been one further RCT reporting methotrexate 7.5 mg orally a week compared with placebo in only 35 patients.105 The cohort had a much higher prevalence of peripheral arthritis than the previous two studies (60% v 12% and 30%). Although significant improvements in the Bath AS Disease Activity Index (BASDAI), spinal pain and the Bath AS Functional Index (BASFI) were seen in the treatment arm, there was no significant difference in effect compared with placebo. Pooling results103,105 gave an effect size for spinal pain of −0.05 (95% CI −0.48 to 0.38) and for function of 0.02 (95% CI −0.40 to 0.45), neither of which reached statistical significance. Roychowdhury et al are the only group to report separate outcomes for patients with peripheral joint involvement, subgroup analysis failing to show any improvement in disease activity with methotrexate in patients with peripheral arthritis, although numbers were small (n = 9).104 There has been one controlled trial, published in abstract form,106 reporting significant improvement in the number of swollen joints in patients with AS with peripheral arthritis with methotrexate 7.5 mg orally a week, NSAID, and physiotherapy (p<0.0001), but results of comparison with the control group of NSAID and physiotherapy alone were not given.

Five meta‐analyses of RCTs of methotrexate treatment102,107,108,109,110 included toxicity data. The most commonly reported side effects of methotrexate treatment at doses equivalent to those used in rheumatological practice include nausea (RR 2.12, 95% CI 1.50 to 2.98) and hepatic abnormalities (RR 4.12, 95% CI 2.22 to 7.63). Other common adverse events recognised at higher doses did not occur significantly more often with treatment than in controls. Ortiz reported a meta‐analysis of the use of folate and/or folinic acid in conjunction with low dose methotrexate treatment in rheumatoid arthritis, and concluded that folate is effective in preventing GI and mucocutaneous adverse events (RR 0.56, 95% CI 0.38 to 0.80),111 but there was no convincing evidence to support the use of folinic acid (RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.39 to 1.12). In patients with AS, an observational study of stopping treatment owing to drug toxicity112 found that 21% of patients had stopped methotrexate treatment by 12 months because of significant adverse events (n = 14).

Pamidronate

Intravenous pamidronate has been studied in open trials,113,114,115,116 with contradictory results. The best available evidence is level III117—a comparative RCT of 60 mg intravenous (IV) pamidronate against 10 mg IV pamidronate, which supports the use of higher dose bisphosphonate for function (ES 0.73, 95% CI 0.29 to 1.17) and for axial pain (p = 0.003, insufficient data given to calculate ES). The authors comment that the study was not powered to show any effect on peripheral arthritis. Further RCTs are needed to answer this question. The most commonly reported side effects of IV pamidronate are transient post‐infusional arthralgias and myalgias (in up to 78% of patients in observational studies114,117,118) and an acute phase response with lymphopenia and raised C reactive protein,119 which rarely lead to treatment discontinuation.

Thalidomide

Thalidomide is receiving increasing attention as a possible treatment for severe AS; to date there have been two open trials published showing significant improvement in axial pain and function,120,121 but effects on peripheral disease have not been reported. Toxicity is substantial, open studies showing consistent problems with drowsiness, dizziness, dry mouth, headache, constipation, and nausea (all >15% incidence rates) and high rates of treatment withdrawal due to side effects.

Other traditional DMARDs used in RA

There is little evidence to support the use of the DMARDs that are used in rheumatoid arthritis in AS. Single case studies support the use of ciclosporin122 and azathioprine.123 There are no studies of efficacy for hydroxychloroquine on musculoskeletal disease in AS, although one case study reports a good result in AS associated iridocyclitis.124 Auranofin treatment was not clinically effective in the only retrieved controlled trial,125 although the study was too small to reflect an effect on the subgroup of patients with peripheral joint disease. Intravenous cyclophosphamide may be effective in severe, active disease associated with peripheral arthritis,126,127 supported by level IV evidence. The only RCT of leflunomide in AS128 failed to show a significant effect on pain (ES 0.14, 95% CI −0.48 to 0.76) or function (ES −0.10, 95% CI −0.72 to 0.52), but was not powered to see any effect on peripheral arthritis, which had been suggested to respond to treatment in an earlier open study.129 Similarly, one RCT of d‐penicillamine in AS was retrieved,130 which found no effect of treatment on pain (level Ib), and case series of peripheral arthritis in AS have failed to show any benefit.131,132

Biological treatments

Tumour necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors

Six placebo RCTs of TNF inhibition in AS were found which examined pain and/or function as separate outcomes. For spinal pain, etanercept (pooled ES 2.25, 95% CI 1.92 to 2.59)133,134,135,136 and infliximab (ES 0.90, 95% CI 0.66 to 1.14)137,138 both gave large improvements, with a pooled ES for spinal pain of 1.36 (95% CI 1.16 to 1.55). Three of these studies reported a moderate effect of treatment on peripheral joint pain,133,135,137 with a pooled ES of 0.61 (95% CI 0.27 to 0.95). Significant effects (pooled ES 1.39, 95% CI 1.20 to 1.57) were also seen for improvement in function, as measured by the BASFI in all studies: for etanercept, the pooled ES was 2.11 (95% CI 1.81 to 2.41) and for infliximab ES was 0.93 (95% CI 0.69 to 1.17). The NNT to achieve an ASAS20 response with infliximab was 2.3 (95% CI 1.9 to 3.0), and for etanercept was 2.7 (95% CI 2.2 to 3.4). Pooling results for both etanercept and infliximab, the NNT with TNF blockers to achieve an ASAS20 response in patients with active disease was 2.6 (95% CI 2.2 to 3.0). To date there is only one AS open trial of adalimumab, the most recent TNF antagonist to become available for treatment in rheumatic diseases, but preliminary data show significant improvements in pain and function.139

TNF blocker related toxicity is an important consideration. RCTs reflect some of the well recognised adverse effects of treatment, including a high incidence of injection site reactions with subcutaneous etanercept (pooled RR from trials in rheumatoid arthritis and AS was calculated at 3.12, 95% CI 2.50 to 3.90 compared with placebo) and development of antinuclear antibodies with intravenous infliximab (pooled RR 2.38, 95% CI 1.61 to 3.53). Other expected toxicities did not reach statistical significance in the RCTs pooled, but the nature of patient selection in such trials and the relatively low incidence of more serious adverse events make it difficult to extrapolate these results to everyday clinical practice. It is important to remember that treatment has been associated with increased risk of infection, both of common upper respiratory tract infections and of opportunistic infections140,141—in particular, tuberculosis.142,143 Screening for Mycobacterium tuberculosis has been shown to decrease the incidence of tuberculous disease associated with TNF blockers,144 and is now a standard prerequisite for TNF blocker treatment. Demyelinating disease,145 lupus‐like syndromes,146,147,148 and worsening of pre‐existent congestive heart failure149,150,151 have also been reported in case series, although precise incidences are not known.

Interleukin 1 inhibitors

The only other non‐TNF biological modifier to be studied in AS to date is the interleukin 1 inhibitor anakinra, again only in open label trials.152,153 Results are not consistent, with one study152 showing a significant improvement in pain (p = 0.04) and function (p = 0.02) and the second,153 failing to find any significant improvements with treatment.

Radiation

Local irradiation

Observational studies154,155,156 and one RCT157 were retrieved showing that local irradiation to the spine and sacroiliac joints in patients with AS is effective for pain relief for up to 12 months (level Ib evidence). Physical function was not assessed. There is a large body of evidence for the carcinogenicity of this treatment,158,159,160,161 particularly for leukaemia (RR 2.74, 95% CI 2.10 to 3.53) and other cancers of irradiated sites (RR 1.26, 95% CI 1.19 to 1.32) compared with patients with AS not treated with x rays.162,163

Intravenous radium‐224 chloride

Intravenous treatment with the radioactive isotope radium chloride (224Ra) is largely of historical interest, and not available today for the treatment of AS in most countries. It was used at high doses in the 1940s and 1950s for the treatment of various bone and joint diseases, including tuberculosis and AS. Such high doses have since been abandoned owing to unacceptable toxicity,164 but lower doses are currently in use since the reintroduction of intravenous 224Ra for AS in Germany in 2000.165224Ra has been shown to be effective for pain and spinal stiffness in AS in observational studies—most uncontrolled (best evidence level IIb).166,167,168,169,170,171,172 There has been no formal assessment of the effect of 224Ra on physical function. Owing to variable study reporting and different study outcome measures it was not possible to calculate pooled ES, but “response” rates reported by patients range from 40% to 90%. Toxicity remains a problem with lower dose treatment, with a significantly higher incidence of myeloid leukaemia and bone malignancies in treated patients compared with the normal population.173

Surgical interventions

Total hip arthroplasty

There were numerous prospective cohort studies of total hip replacement (THR) in AS, but RCTs were limited to comparisons between surgical techniques and therefore beyond the scope of this review. The largest case series to date reviewed 340 hips with a mean follow up of 14 years, and showed that 83% of patients reported good to excellent pain relief, and 52% good to excellent functional improvement after the procedure.174 Patients undergoing surgery were younger (mean age 40 years) than comparative cohorts undergoing THR for other indications such as osteoarthritis.175 Results from large databases of THR show that age and sex, independent of joint disease, predict revision.176 However, revision rates in the study group174 were not unduly high, with a 90% survival probability at 10 years, and 65% at 20 years. Joint revisions were also seen to perform well, with a 20 year survival of 61%. Most failures occurred within the first 7 years, and were most often due to prosthesis loosening. A high incidence of heterotopic bone formation and re‐ankylosis after THR has been reported in early studies of THR in AS177,178; however, rates are much lower in contemporary studies.179,180,181,182

Spinal surgery

Surgery for fixed kyphotic deformity causing major disability can give excellent functional results by restoring balance and horizontal vision and relieving intra‐abdominal pressure. It is not clear which of the three commonly performed procedures, opening wedge osteotomy, polysegmental wedge osteotomy, and closing wedge osteotomy, gives the best results for any specific indication.183 Correction ranges from 10° to 60° in different series.184,185,186,187,188,189,190,191,192,193,194 Rates of complications vary markedly between studies, opening wedge osteotomy being the only procedure reported to be associated with permanent neurological complications.184 Instrumentation failure has been commonly reported, in up to 33% of cases in one series.187 Surgery for other indications in AS is uncommon, and large series are lacking in the literature. A case review of operative compared with non‐operative treatment for spinal fracture with neurological deficit in AS did not show any differences in outcome between the groups. However, the length of hospital stay was shorter in the non‐operative group and hence costs were lower in that group.195 Operative results in small case series have shown high mortality (16–29%).196,197

Discussion

This systematic literature review identified available treatments effective for symptomatic control of spinal pain and physical function in AS. Both NSAIDs and coxibs have large effects on spinal pain and moderate benefit for physical function. TNF inhibitors are effective in patients with active disease, with large benefits seen in pain and function. Results with other traditional DMARDs are less encouraging, without convincing evidence of an effect on the spinal symptoms of AS, although there may be a role for sulfasalazine or methotrexate in the treatment of peripheral joint disease. Total hip arthroplasty is valuable in patients with significant hip disease, and spinal surgery can be useful in selected patients. Non‐pharmacological treatments are also supported by current research evidence for maintaining function in patients with AS.

It is less clear if any treatments modify disease progression; this literature review was designed to answer the question “what interventions have an effect on pain or function in AS” and as such was not directed at the effect of treatment on structural changes. Continuing studies of TNF inhibitors in AS over 2 and 3 years are now beginning to answer this important question.

As with any literature review, this study is limited by the unavoidable publication bias associated with clinical trials, where trials with positive results are more frequently published than negative studies. This may have resulted in an overestimation of true clinical efficacy. The variable quality of the reporting of clinical trials before the CONSORT statement for standardisation of the reporting of clinical trials198,199 was published also contributes potential bias—for example, when specific information could not be retrieved from the paper and the authors could not be contacted.

This review is a comprehensive summary of the current “best evidence” available for therapeutic interventions, both pharmacological and non‐pharmacological, for the management of AS, and formed the basis for the development of the ASAS/EULAR recommendations for management of AS.1

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support of EULAR, and the valuable assistance of the following people in the preparation of this manuscript: H Böhm, R Burgos‐Vargas, E Collantes, J Davis, B Dijkmans, P Géher, R Inman, MA Khan, T Kvien, M Leirisalo‐Repo, I Olivieri, K Pavelka, J Sieper, G Stucki, R Sturrock, S van der Linden, BJ van Royen, and D Wendling.

Abbreviations

AS - ankylosing spondylitis

ASAS - ASsessment in AS

CI - confidence interval

DMARDs - disease modifying antirheumatic drugs

ES - effect size

GI - gastrointestinal

IV - intravenous

MeSH - medical subject heading

NNT - number needed to treat

NSAIDs - non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs

RCT - randomised controlled trial

RR - relative risk

THR - total hip replacement

TNF - tumour necrosis factor

APPENDIX 1 SEARCH STRATEGY FOR ANKYLOSING SPONDYLITIS

Database: Ovid MEDLINE(R) <1966 to December Week 4 2004>

Search Strategy:

1 exp ANKYLOSING SPONDYLITIS/ (7445)

2 spondyloarthr$.mp. (1620)

3 ankylosi$.mp. (8424)

4 syndesmophyt$.mp. (113)

5 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 (12302)

6 limit 5 to human (2433)

APPENDIX 2 SEARCH STRATEGY FOR TYPES OF EVIDENCE

Database: Ovid MEDLINE(R) <1966 to December Week 4 2004>

Search Strategy:

1 systematic review$.mp. (6835)

2 exp meta‐analysis/ (5713)

3 meta‐analysis$.mp. [mp = title, abstract, name of substance, mesh subject heading] (14204)

4 exp systematic review/ (0)

5 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 (19490)

6 limit 5 to human (18685)

7 cohort stud$.mp. or exp Cohort Studies/ (520224)

8 case control stud$.mp. or exp Case‐Control Studies/ (277571)

9 cross sectional stud$.mp. or exp Cross sectional Studies/ (60617)

10 risk ratio$.mp. or exp Odds Ratio/ (25051)

11 relative risk$.mp. (27401)

12 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 (811260)

13 limit 12 to human (796187)

14 exp “Costs and Cost Analysis”/ or exp Cost‐Benefit Analysis/ or economic evaluation.mp. or exp Economics, Medical/ (121450)

15 cost effectiveness analys$.mp. (2713)

16 cost utility analys$.mp. (473)

17 cost minimisation analys$.mp. (170)

18 cost benefit analys$.mp. (34956)

19 cost analys$.mp. (2319)

20 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 (122698)

21 limit 20 to human (87101)

22 exp Randomised Controlled Trials/ or randomised controlled trial$.mp.

or exp Clinical Trials/ or exp Random Allocation/ (208880)

23 exp Double‐Blind Method/ or double blind.mp. or exp Placebos/ (111321)

24 single blind.mp. or exp Single‐Blind Method/ (11613)

25 Comparative Study/ (1188913)

26 prospective stud$.mp. or exp Prospective Studies/ (200630)

27 follow up stud$.mp. or exp Follow‐Up Studies/ (301986)

28 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27 (1769477)

29 limit 28 to human (1342425)

30 6 or 13 or 21 or 29 (1697116)

References

- 1.Zochling J, van der Heijde D, Burgos‐Vargas R, Collantes E, Davis J, Dijkmans B.et al ASAS/EULAR recommendations for the management of ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 200665442–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shekelle P G, Woolf S H, Eccles M, Grimshaw J. Clinical guidelines: developing guidelines. BMJ 1999318593–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hedges L V. Fitting continuous models to effect size data. J Educat Stat 19827245–270. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cook R J, Sackett D L. The number needed to treat: a clinically useful measure of treatment effect. BMJ 1995310452–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whitehead A, Whitehead J. A general parametric approach to the meta‐analysis of randomized clinical trials. Stat Med 1991101665–1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Altman D G. Confidence intervals for the number needed to treat. BMJ 19983171309–1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dagfinrud H, Kvien T K, Hagen K. Physiotherapy interventions for ankylosing spondylitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004(4)CD002822. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Kraag G, Stokes B, Groh J, Helewa A, Goldsmith C. The effects of comprehensive home physiotherapy and supervision on patients with ankylosing spondylitis—a randomized controlled trial. J Rheumatol 199017228–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kraag G, Stokes B, Groh J, Helewa A, Goldsmith C H. The effects of comprehensive home physiotherapy and supervision on patients with ankylosing spondylitis—an 8‐month followup. J Rheumatol 199421261–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hidding A, van der Linden S, Boers M, Gielen X, de Witte L, Kester A.et al Is group physical therapy superior to individualized therapy in ankylosing spondylitis? A randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Care Res 19936117–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bakker C, Hidding A, van der Linden S, Van Doorslaer E. Cost effectiveness of group physical therapy compared to individualized therapy for ankylosing spondylitis. A randomized controlled trial. J Rheumatol 199421264–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Helliwell P S, Abbott C A, Chamberlain M A. A randomised trial of three different physiotherapy regimes in ankylosing spondylitis. Physiotherapy 19968285–90. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Analay Y, Ozcan E, Karan A, Diracoglu D, Aydin R. The effectiveness of intensive group exercise on patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Rehabil 200317631–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sweeney S, Taylor G, Calin A. The effect of a home based exercise intervention package on outcome in ankylosing spondylitis: a randomized controlled trial. J Rheumatol 200229763–766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lim H ‐ J, Moon Y ‐ I, Lee M S. Effects of home‐based daily exercise therapy on joint mobility, daily activity, pain, and depression in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatol Int 200525225–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gemignani G, Olivieri I, Ruju G, Pasero G. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation in ankylosing spondylitis: a double‐blind study. Arthritis Rheum 199134788–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bulstrode S J, Barefoot J, Harrison R A, Clarke A K. The role of passive stretching in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis. Br J Rheumatol 19872640–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trotta F, Bassoli J, Manicardi S. Effect of pulsed magnetic fields on the pain of seronegative spondyloarthritis. Bioelectrochem Bioenerg 198514183–186. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Samborski W, Sobieska M, Mackiewicz T, Stratz T, Mennet M, Muller W. Can thermal therapy of ankylosing spondylitis induce an activation of the disease? Z Rheumatol 199251127–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zielke V A, Just L, Schubert M, Tautenhahn B. Objective evaluation of complex balneotherapy based on radon in ankylosing spondylitis and rheumatoid arthritis (summary index of functions). Z Physiother 197325113–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hashkes P J. Beneficial effect of climatic therapy on inflammatory arthritis at Tiberias Hot Springs. Scand J Rheumatol 200231172–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Metzger D, Swingmann C, Protz W, Jackel W H. The whole body cold therapy as analgesic treatment in patients with rheumatic diseases. Rehabilitation 20003993–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tishler M, Brostovski Y, Yaron M. Effect of spa therapy in Tiberias on patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Rheumatol 19951421–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Tubergen A, Landewe R, van der Heijde D, Hidding A, Wolter N, Asscher M.et al Combined spa‐exercise therapy is effective in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 200145430–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Tubergen A, Boonen A, Landewe R, Rutten‐van Molken M, van der Heijde D, Hidding A.et al Cost effectiveness of combined spa‐exercise therapy in ankylosing spondylitis: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 200247459–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barlow J H, Barefoot J. Group education for people with arthritis. Pt Educat Counsel 199627257–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Basler H D, Rehfisch H P. Cognitive‐behavioral therapy in patients with ankylosing spondylitis in a German self‐help organization. J Psychosom Res 199135345–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krauth C, Rieger J, Bonisch A, Ehlebracht‐Konig I. Costs and benefits of an education program for patients with ankylosing spondylitis as part of an inpatient rehabilitation programs‐study design and first results. Z Rheumatol 200362II14–II16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Buck P D M, Schoones J W, Allaire S H, Vliet Vlieland T P M. Vocational rehabilitation in patients with chronic rheumatic diseases: a systematic literature review. Semin Arthritis Rheum 200232196–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Averns H L, Oxtoby J, Taylor H G, Jones P W, Dziedzic K, Dawes P T. Smoking and outcome in ankylosing spondylitis. Scand J Rheumatol 199625138–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Doran M F, Brophy S, MacKay K, Taylor G, Calin A. Predictors of longterm outcome in ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol 200330316–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ward M M. Predictors of the progression of functional disability in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol 2002291420–1425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ebringer A, Wilson C. The use of a low starch diet in the treatment of patients suffering from ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Rheumatol 19961562–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ebringer A, Baines M, Childerstone M, Ghuloom M, Ptaszynska T. Etiopathogenesis of ankylosing spondylitis and the cross‐tolerance hypothesis. Adv Inflamm Res 19859101–128. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Appelboom T, Durez P. Effect of milk product deprivation on spondyloarthropathy. Ann Rheum Dis 199453481–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dougados M, Nguyen M, Caporal R, Legeais J, Bouxin‐Sauzet A, Pellegri‐Guegnault B.et al Ximoprofen in ankylosing spondylitis. A double blind placebo controlled dose ranging study. Scand J Rheumatol 199423243–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dougados M, Caporal R, Doury P, Thiesce A, Pattin S, Laffez B.et al A double blind crossover placebo controlled trial of ximoprofen in ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol 1989161167–1169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jajic I, Nekora A, Chadri H A. Pirprofen, indomethacin and placebo in ankylosing spondylitis. Double‐blind comparison. Nouv Presse Med 1982112491–2493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Calcraft B, Tildesley G, Evans K T, Gravelle H, Hole D, Lloyd K N. Azapropazone in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis: a controlled clinical trial. Rheumatol Rehabil 19741323–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sturrock R D, Hart F D. Double‐blind cross‐over comparison of indomethacin, flurbiprofen, and placebo in ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 197433129–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dougados M, Gueguen A, Nakache J P, Velicitat P, Veys E M, Zeidler H.et al Ankylosing spondylitis: what is the optimum duration of a clinical study? A one year versus a 6 weeks non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drug trial. Rheumatology (Oxford) 199938235–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dougados M, Behier J M, Jolchine I, Calin A, van der Heijde D, Olivieri I.et al Efficacy of celecoxib, a cyclooxygenase 2‐specific inhibitor, in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis: a six‐week controlled study with comparison against placebo and against a conventional nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug. Arthritis Rheum 200144180–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van der Heijde D, Baraf H S B, Ramos‐Remus C, Calin A, Weaver A L, Schiff M.et al Evaluation of the efficacy of etoricoxib in ankylosing spondylitis: results of a 52‐week randomized controlled study. Arthritis Rheum 2005521205–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gossec L, van der Heijde D, Melian A, Krupa D A, James M K, Cavanaugh P F.et al Efficacy of cyclo‐oxygenase‐2 inhibition by etoricoxib and naproxen on the axial manifestations of ankylosing spondylitis in the presence of peripheral arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2005641563–1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ansell B M, Major G, Liyanage S P, Gumpel J M, Seifert M H, Mathews J A.et al A comparative study of Butacote and Naprosyn in ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 197837436–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Astorga G. Double‐blind, parallel clinical trial of tenoxicam (Ro 12‐0068) versus piroxicam in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Eur J Rheum Inflamm 1987970–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Batlle‐Gualda E, Figueroa M, Ivorra J, Raber A. The efficacy and tolerability of aceclofenac in the treatment of patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a multicenter controlled clinical trial. Aceclofenac Indomethacin Study Group. J Rheumatol 1996231200–1206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bernstein R M, Calin H J, Ollier S, Calin A. A comparison of the efficacy and tolerability of lornoxicam and indomethacin in ankylosing spondylitis. Eur J Rheum Inflamm 1992126–13. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bird H A, Rhind V M, Pickup M E, Wright V. A comparative study of benoxaprofen and indomethacin in ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol 19806139–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Calin A, Grahame R. Double‐bind cross‐over tiral of flurbiprofen and phenylbutazone in ankylosing spondylitis. BMJ 19744496–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carcassi C, La Nasa G, Perpignano G. A 12‐week double‐blind study of the efficacy, safety and tolerance of pirazolac b.i.d. compared with indomethacin t.i.d. in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Drugs Exptl Clin Res 19901629–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Charlot J, Villiaumey J. A comparative study of benoxaprofen and ketoprofen in ankylosing spondylitis. Eur J Rheum Inflamm 19825277–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Doury P, Roux H. Isoxicam vs ketoprofen in ankylosing spondylitis. Br J Clin Pharmacol 198622(suppl 2)157–60S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Franssen M J, Gribnau F W, van de Putte L B. A comparison of diflunisal and phenylbutazone in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Rheumatol 19865210–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Harkness A J, Burry H C, Grahame R. A trial of feprazone in ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatol Rehabil 197716158–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jessop J D. Double‐blind study of ketoprofen and phenylbutazone in ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatol Rehabil 1976(suppl)37–42. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Khan M A. Diclofenac in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis: review of worldwide clinical experience and report of a double‐blind comparison with indomethacin. Semin Arthritis Rheum 19851580–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lomen P L, Turner L F, Lamborn K R, Brinn E L, Sattler L P. Flurbiprofen in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis. A comparison with phenylbutazone. Am J Med 198680120–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Myklebust G. Comparison of naproxen and piroxicam in rheumatoid arthritis and Bechterew's syndrome. A double‐blind parallel multicenter study. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 19861061485–1487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nahir A M, Scharf Y. A comparative study of diclofenac and sulindac in ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatol Rehabil 198019193–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nissila M, Kajander A. Proquazone (Biarison) and indomethacin (Indocid) in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis. Two comparative, clinical, double‐blind studies. Scand J Rheumatol 19782136–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Palferman T G, Webley M. A comparative study of nabumetone and indomethacin in ankylosing spondylitis. Eur J Rheum Inflamm 19911123–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pasero G, Ruju G, Marcolongo R, Senesi M, Serni U, Mannoni A.et al Aceclofenac versus naproxen in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis: a double‐blind, controlled study. Curr Ther Res 199455833–842. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Renier J C, Fournier M, Loyau G, Roux H. Ankylosing spondylitis. Comparative trial of two non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory agents: pirprofen and ketoprofen, Nouv Presse Med 1982112494–2496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schattenkirchner M, Kruger K. NSAIDs in ankylosing spondylitis. The importance of tolerability during long‐term treatment. Therapiewoche 199242438–449. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schwarzer A C, Cohen M, Arnold M H, Kelly D, McNaught P, Brooks P M. Tenoxicam compared with diclofenac in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Curr Med Res Opin 199011648–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Simpson M R, Simpson N R, Scott B O, Beatty D C. A controlled study of flufenamic acid in ankylosing spondylitis. A preliminary report. Ann Phys Med 1966(suppl)126–128. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 68.Stollenwerk R, von Criegern T, Gierend M, Schilling F. Therapy of ankylosing spondylitis. Short‐term use of piroxicam suppositories or indomethacin suppositories and retard capsules. Fortschr Med 1985103561–565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Villa Alcazar L F, de Buergo M, Rico L H, Montull F E. Aceclofenac is as safe and effective as tenoxicam in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis: a 3 month multicenter comparative trial. Spanish Study Group on Aceclofenac in Ankylosing Spondylitis. J Rheumatol 1996231194–1199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wasner C, Britton M C, Kraines R G, Kaye R L, Bobrove A M, Fries J F. Nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory agents in rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis. JAMA 19812462168–2172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang W, Doherty M, Arden N, Bannwarth B, Bijlsma J, Gunther K P.et al EULAR evidence based recommendations for the management of hip osteoarthritis: report of a task force of the EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis 200564669–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bollini P, Garcia Rodriguez L A, Perez G S, Walker A M. The impact of research quality and study design on epidemiologic estimates of the effect of nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs on upper gastrointestinal tract disease. Arch Intern Med 19921521289–1295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gabriel S E, Jaakkimainen L, Bombardier C. Risk for serious gastrointestinal complications related to use of nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs. A meta‐analysis. Ann Intern Med 1991115787–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Garcia Rodriguez L A. Variability in risk of gastrointestinal complications with different nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs. Am J Med 199810430–4S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lewis S C, Langman M J, Laporte J R, Matthews J N, Rawlins M D, Wiholm B E. Dose‐response relationships between individual nonaspirin nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NANSAIDs) and serious upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a meta‐analysis based on individual patient data. Br J Clin Pharmacol 200254320–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ofman J J, MacLean C H, Straus W L, Morton S C, Berger M L, Roth E A.et al A metaanalysis of severe upper gastrointestinal complications of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. J Rheumatol 200229804–812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tramer M R, Moore R A, Reynolds D J, McQuay H J. Quantitative estimation of rare adverse events which follow a biological progression: a new model applied to chronic NSAID use. Pain 200085169–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Capurso L, Koch M. Prevention of NSAID‐induced gastric lesions: H2 antagonists or misoprostol? A meta‐analysis of controlled clinical studies. Clin Ter 1991139179–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Koch M, Dezi A, Ferrario F, Capurso I. Prevention of nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drug‐induced gastrointestinal mucosal injury. A meta‐analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Arch Intern Med 19961562321–2332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Leandro G, Pilotto A, Franceschi M, Bertin T, Lichino E, Di Mario F. Prevention of acute NSAID‐related gastroduodenal damage: a meta‐analysis of controlled clinical trials. Dig Dis Sci 2001461924–1936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rostom A, Wells G, Tugwell P, Welch V, Dube C, McGowan J. The prevention of chronic NSAID induced upper gastrointestinal toxicity: a Cochrane collaboration metaanalysis of randomized controlled trials. J Rheumatol 2000272203–2214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shield M J. Diclofenac/misoprostol: novel findings and their clinical potential. J Rheumatol 19982531–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Deeks J J, Smith L A, Bradley M D. Efficacy, tolerability, and upper gastrointestinal safety of celecoxib for treatment of osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: systematic review of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2002325619–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Juni P, Nartey L, Reichenbach S, Sterchi R, Dieppe P A, Egger M. Risk of cardiovascular events and rofecoxib: cumulative meta‐analysis. Lancet 20043642021–2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bresalier R S, Sandler R S, Quan H, Bolognese J A, Oxenius B, Horgan K.et al Cardiovascular events associated with rofecoxib in a colorectal adenoma chemoprevention trial. N Engl J Med 20053521092–1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Solomon S D, McMurray J J V, Pfeffer M A, Wittes J, Fowler R, Finn P.et al Cardiovascular risk associated with celecoxib in a clinical trial for colorectal adenoma prevention. N Engl J Med 20053521071–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nussmeier N A, Whelton A A, Brown M T, Langford R M, Hoeft A, Parlow J L.et al Complications of the COX‐2 inhibitors parecoxib and valdecoxib after cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med 20053521081–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Pal B. Use of simple analgesics in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis. Br J Rheumatol 198726207–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Maugars Y, Mathis C, Berthelot J M, Charlier C, Prost A. Assessment of the efficacy of sacroiliac corticosteroid injections in spondylarthropathies: a double‐blind study. Br J Rheumatol 199635767–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Luukkainen R, Nissila M, Asikainen E, Sanila M, Lehtinen K, Alanaatu A.et al Periarticular corticosteroid treatment of the sacroiliac joint in patients with seronegative spondylarthropathy. Clin Exp Rheumatol 19991788–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Green M, Marzo‐Ortega H, Wakefield R J, Astin P, Proudman S, Conaghan P G.et al Predictors of outcome in patients with oligoarthritis: results of a protocol of intraarticular corticosteroids to all clinically active joints. Arthritis Rheum 2001441177–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ejstrup L, Peters N D. Intravenous methylprednisolone pulse therapy in ankylosing spondylitis. Dan Med Bull 198532231–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mintz G, Enriquez R D, Mercado U, Robles E J, Jimenez F J, Gutierrez G. Intravenous methylprednisolone pulse therapy in severe ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum 198124734–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Richter M B, Woo P, Panayi G S, Trull A, Unger A, Shepherd P. The effects of intravenous pulse methylprednisolone on immunological and inflammatory processes in ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 19835351–59. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Peters N D, Ejstrup L. Intravenous methylprednisolone pulse therapy in ankylosing spondylitis. Scand J Rheumatol 199221134–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Chen J, Liu C. Sulfasalazine for ankylosing spondylitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005(2)CD004800. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 97.Dougados M, van der Linden S, Leirisalo‐Repo M, Huitfeldt B, Juhlin R, Veys E.et al Sulfasalazine in the treatment of spondylarthropathy. A randomized, multicenter, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study. Arthritis Rheum 199538618–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Clegg D O, Reda D J, Abdellatif M. Comparison of sulfasalazine and placebo for the treatment of axial and peripheral articular manifestations of the seronegative spondylarthropathies: a Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative study. Arthritis Rheum 1999422325–2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kirwan J, Edwards A, Huitfeldt B, Thompson P, Currey H. The course of established ankylosing spondylitis and the effects of sulphasalazine over 3 years. Br J Rheumatol 199332729–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lehtinen A, Leirisalo‐Repo M, Taavitsainen M. Persistence of enthesopathic changes in patients with spondyloarthropathy during a 6‐month follow‐up. Clin Exp Rheumatol 199513733–736. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Dekker‐Saeys B J, Dijkmans B A, Tytgat G N. Treatment of spondyloarthropathy with 5‐aminosalicylic acid (mesalazine): an open trial. J Rheumatol 200027723–726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Chen J, Liu C. Methotrexate for ankylosing spondylitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004(3)CD004524. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 103.Altan L, Bingol U, Karakoc Y, Aydiner S, Yurtkuran M, Yurtkuran M. Clinical investigation of methotrexate in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis. Scand J Rheumatol 200130255–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Roychowdhury B, Bintley‐Bagot S, Bulgen D Y, Thompson R N, Tunn E J, Moots R J. Is methotrexate effective in ankylosing spondylitis? Rheumatology (Oxford) 2002411330–1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Gonzalez‐Lopez L, Garcia‐Gonzalez A, Vazquez‐Del‐Mercado M, Munoz‐Valle J F, Gamez‐Nava J I. Efficacy of methotrexate in ankylosing spondylitis: a randomized, double blind, placebo controlled trial. J Rheumatol 2004311568–1574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Pišev K, Æirkoviæ M, Glišiæ B, Popoviæ R, Stefanoviæ D. Efficacy of low dose methotrexate (MTX) in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis (AS) with arthritis [abstract]. J Rheumatol 20012859 [Google Scholar]

- 107.Davies H. Methotrexate as a steroid sparing agent for asthma in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004(2)CD000391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 108.Suarez‐Almazor M, Belseck E, Shea B, Wells G, Tugwell P. Methotrexate for treating rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004(2)CD000957. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 109.Takken T. Methotrexate for treating juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004(4)CD003129. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 110.Alfadhli A, McDonald J, Feagan B. Methotrexate for induction of remission in refractory Crohn's disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004(1)CD003459. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 111.Ortiz Z. Folic acid and folinic acid for reducing side effects in patients receiving methotrexate for rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1999(4)CD000951. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 112.Ward M M, Kuzis S. Medication toxicity among patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum 200247234–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Maksymowych W P, Jhangri G S, LeClercq S, Skeith K J, Yan A, Russell A S. An open study of pamidronate in the treatment of refractory ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol 199825714–717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Maksymowych W P, Lambert R, Jhangri G S, LeClercq S, Chiu P, Wong B.et al Clinical and radiological amelioration of refractory peripheral spondyloarthritis by pulse intravenous pamidronate therapy. J Rheumatol 200128144–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Haibel H, Brandt J, Rudwaleit M, Soerensen H, Sieper J, Braun J. Treatment of active ankylosing spondylitis with pamidronate. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2003421018–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Cairns A P, Wright S A, Taggart A J, Coward S M, Wright G D. An open study of pulse pamidronate treatment in severe ankylosing spondylitis, and its effect on biochemical markers of bone turnover. Ann Rheum Dis 200564338–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Maksymowych W P, Jhangri G S, Fitzgerald A A, LeClercq S, Chiu P, Yan A.et al A six‐month randomized, controlled, double‐blind, dose‐response comparison of intravenous pamidronate (60 mg versus 10 mg) in the treatment of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug‐refractory ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum 200246766–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Maksymowych W P, Jhangri G S, LeClercq S, Skeith K, Yan A, Russell A S. An open study of pamidronate in the treatment of refractory ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol 199825714–717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Adami S, Bhalla A K, Dorizzi R, Montesanti F, Rosini S, Salvagno G.et al The acute‐phase response after bisphosphonate administration. Calcif Tiss Int 198741326–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Wei J C, Chan T W, Lin H, Huang F, Chou C. Thalidomide for severe refractory ankylosing spondylitis: a 6‐month open‐label trial. J Rheumatol 2003302627–2631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Huang F, Gu J, Zhao W, Zhu J, Zhang J, Yu D T Y. One‐year open‐label trial of thalidomide in ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Care Res 20024715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Geher P, Gomor B. Repeated cyclosporine therapy of peripheral arthritis associated with ankylosing spondylitis. Med Sci Monitor 20017105–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Durez P, Horsmans Y. Dramatic response after an intravenous loading dose of azathioprine in one case of severe and refractory ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 200039182–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Giordano M. Long‐term prophylaxis of recurring spondylitic iridocyclitis with antimalarials and non‐steroidal antiphlogistics. Z Rheumatol 198241105–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Grasedyck K, Schattenkirchner M, Bandilla K. The treatment of ankylosing spondylitis with auranofin (Ridaura). Z Rheumatol 19904998–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Sadowska‐Wroblewska M, Garwolinska H, Maczynska‐Rusiniak B. A trial of cyclophosphamide in ankylosing spondylitis with involvement of peripheral joints and high disease activity. Scand J Rheumatol 198615259–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Fricke R, Petersen D. Treatment of ankylosing spondylitis with cyclophosphamide and azathioprine. Verh Dtsch Ges Rheumatol 19691189–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Van Denderen J C, van der Paardt M, Nurmohamed M T, de Ryck Y M M A, Dijkmans B A C, van der Horst‐Bruinsma I E. Double blind, randomised, placebo‐controlled study of leflunomide in the treatment of active ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 2005641761–1764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Haibel H, Rudwaleit M, Braun J, Sieper J. Six months open label trial of leflunomide in active ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 200564124–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Steven M M, Morrison M, Sturrock R D. Penicillamine in ankylosing spondylitis: a double blind placebo controlled trial. J Rheumatol 198512735–737. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Bird H A, Dixon A S. Failure of D‐penicillamine to affect peripheral joint involvement in ankylosing spondylitis or HLA B27‐associated arthropathy. Ann Rheum Dis 197736289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Jaffe I A. Penicillamine in seronegative polyarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 197736593–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Gorman J D, Sack K E, Davis J C., Jr Treatment of ankylosing spondylitis by inhibition of tumor necrosis factor alpha. N Engl J Med 20023461349–1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Davis J C, Jr, van der Heijde D, Braun J, Dougados M, Cush J, Clegg D O.et al Recombinant human tumor necrosis factor receptor (etanercept) for treating ankylosing spondylitis: a randomized, controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2003483230–3236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Brandt J, Khariouzov A, Listing J, Haibel H, Sorensen H, Grassnickel L.et al Six‐month results of a double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial of etanercept treatment in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum 2003481667–1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Calin A, Dijkmans B A, Emery P, Hakala M, Kalden J, Leirisalo‐Repo M.et al Outcomes of a multicentre randomised clinical trial of etanercept to treat ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 2004631594–1600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Braun J, Brandt J, Listing J, Zink A, Alten R, Golder W.et al Treatment of active ankylosing spondylitis with infliximab: a randomised controlled multicentre trial. Lancet 20023591187–1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.van der Heijde D, Dijkmans B, Geusens P, Sieper J, DeWoody K, Williamson P.et al Efficacy and safety of infliximab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Results of a randomized controlled trial (ASSERT). Arthritis Rheum 200552582–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Haibel H, Brandt H C, Rudwaleit M, Listing J, Braun J, Kupper H.et al Efficacy and safety of adalimumab in the treatment of active ankylosing spondylitis: preliminary results of an open‐label, 20‐week trial [abstract]. Arthritis Rheum 200450S217 [Google Scholar]

- 140.Lee J ‐ H, Slifman N R, Gershon S K, Edwards E T, Schwieterman W D, Siegel J N.et al Life‐threatening histoplasmosis complicating immunotherapy with tumor necrosis factor a antagonists infliximab and etanercept. Arthritis Rheum 2002462565–2570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Slifman N R, Gershon S K, Lee J – H, Edwards E T, Braun M M. Listeria monocytogenes infection as a complication of treatment with tumor necrosis factor a‐neutralizing agents. Arthritis Rheum 200348319–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Keystone E C. Safety issues related to emerging therapies for rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 200422S148–S150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Baeten D, Kruithof E, Van den Bosch F, Van den Bossche N, Herssens A, Mielants H.et al Systematic safety follow up in a cohort of 107 patients with spondyloarthropathy treated with infliximab: a new perspective on the role of host defence in the pathogenesis of the disease? Ann Rheum Dis 200362829–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Gomez‐Reino J J, Carmona L, Valverde V R, Mola E M, Montero M D, BIOBADASER Group Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors may predispose to significant increase in tuberculosis risk: a multicenter active‐surveillance report. Arthritis Rheum 2003482122–2127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Mohan N, Edwards E T, Cupps T R, Oliverio P J, Sandberg G, Crayton H.et al Demyelination occurring during anti‐tumor necrosis factor a therapy for inflammatory arthritides. Arthritis Rheum 2001442862–2869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Ferraccioli G F, Assaloni R, Perin A, Shakoor N, Block J A, Mohan A K.et al Drug‐induced systemic lupus erythematosus and TNF‐a blockers (multiple letters). Lancet 2002360645–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Shakoor N, Michalska M, Harris C A, Block J A. Drug‐induced systemic lupus erythematosus associated with etanercept therapy. Lancet 2002359579–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Cairns A P, Duncan M K J, Hinder A E, Taggart A J. New onset systemic lupus erythematosus in a patient receiving etanercept for rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2002611031–1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Chung E S, Packer M, Lo K H, Fasanmade A A, Willerson J T, Anti‐TNF Therapy Against Congestive Heart Failure Investigators Randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, pilot trial of infliximab, a chimeric monoclonal antibody to tumor necrosis factor‐alpha, in patients with moderate‐to‐severe heart failure: results of the anti‐TNF Therapy Against Congestive Heart Failure (ATTACH) trial. Circulation 20031073133–3140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Coletta A P, Clark A L, Banarjee P, Cleland J G. Clinical trials update: RENEWAL (RENAISSANCE and RECOVER) and ATTACH. Eur J Heart Failure 20024559–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Wolfe F, Michaud M S. Congestive heart failure in rheumatoid arthritis: rates, predictors and the effect of anti‐TNF therapy. Am J Med 2004116311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Tan A L, Marzo‐Ortega H, O'Connor P, Fraser A, Emery P, McGonagle D. Efficacy of anakinra in active ankylosing spondylitis: A clinical and magnetic resonance imaging study. Ann Rheum Dis 2004631041–1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Haibel H, Rudwaleit M, Listing J, Sieper J. Open label trial of anakinra in active ankylosing spondylitis over 24 weeks. Ann Rheum Dis 200564296–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Schuler B, Dihlmann W. Results of x‐ray treatment in ankylosing spondylitis. Verh Dtsch Ges Rheumatol 19691124–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Wilkinson M, Bywaters E G. Clinical features and course of ankylosing spondylitis; as seen in a follow‐up of 222 hospital referred cases. Ann Rheum Dis 195817209–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Fulton J S. Ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Radiol 196112132–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Desmarais M H L. Radiotherapy in arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 19531225–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Brown W M C, Doll R. Mortality from cancer and other causes after radiotherapy for ankylosing spondylitis. BMJ 1965ii1327–1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Weiss H A, Darby S C, Fearn T, Doll R. Leukemia mortality after X‐ray treatment for ankylosing spondylitis. Radiat Res 19951421–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Weiss H A, Darby S C, Doll R. Cancer mortality following X‐ray treatment for ankylosing spondylitis. Int J Cancer 199459327–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Kaprove R E, Little A H, Graham D C, Rosen P S. Ankylosing spondylitis: survival in men with and without radiotherapy. Arthritis Rheum 19802357–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Weiss H A, Darby S C, Fearn T, Doll R. Leukemia mortality after X‐ray treatment for ankylosing spondylitis. Radiat Res 19951421–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Weiss H A, Darby S C, Doll R. Cancer mortality following X‐ray treatment for ankylosing spondylitis. Int J Cancer 199459327–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Nekolla E A, Kellerer A M, Kuse‐Isingschulte M, Eder E, Spiess H. Malignancies in patients treated with high doses of radium‐224. Radiation Res 1999152(suppl)S3–S7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Kommission Pharmakotherapie Position of the German Society of Rheumatology on therapy of ankylosing spondylitis (AS) with radium chloride (224SpondylAT). Z Rheumatol 20016084–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Koch W. Indications and results of radium 224 (thorium X) therapy of ankylosing spondylitis. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb 1978116608–616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Schmitt E. Long‐term study on the therapeutic effect of radium 224 in Bechterew's disease. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb 1978116621–624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Schmitt E, Ruckbeil C, Wick R R. Long‐term clinical investigation of patients with ankylosing spondylitis treated with 224Ra. Health Physics 198344(suppl 1)197–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Knop J, Stritzke P, Heller M, Redeker S, Crone‐Munzebrock W. Results of radium 224 therapy in ankylosing spondylitis (Strumpell‐Marie‐Bechterew disease). Z Rheumatol 198241272–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Redeker S, Crone‐Munzebrock W, Weh L, Montz R. Scintigraphic, radiologic and clinical results after radium 224 therapy in 53 patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Beitr Orthop Traumatol 198229218–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Biskop M, Arnold W, Weber C, Reinwald A K, Reinwald H. Can radium 224 (thorium X) effect the progression of Bechterew's disease? Beitr Orthop Traumatol 198330374–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Seyfarth H. Experience with treatment of ankylosing spondylitis in the GDR: radium‐224 therapy. Akt Rheumatol 19871226–29. [Google Scholar]