Abstract

Background

The efficacy and safety of anakinra, a recombinant human interleukin 1 (IL1) receptor antagonist used in rheumatoid arthritis, has been documented in five randomised controlled studies. However, long term post‐marketing efficacy data are lacking.

Objective

To evaluate the efficacy, safety, and drug survival of anakinra in clinical practice.

Methods

All patients with rheumatoid arthritis who started anakinra in six hospitals between May 2002 and February 2004 were included in a two year prospective, in part retrospective, cohort study. Efficacy was assessed using the 28 joint disease activity score (DAS28) and the EULAR response criteria. Safety was evaluated using the common toxicity criteria. Drug survival and prognostic factors were analysed using Kaplan–Meier and Cox proportional hazard analyses.

Results

After three months, 55% of the patients (n = 146) showed a response (43% moderate, 12% good). A subset of patients continuing anakinra after 18 months had a sustained clinical response compared with patients who switched to other disease modifying antirheumatic drug treatment (DAS28 improvement, 2.46 v 1.79). Drug survival was 78%, 54%, and 14% after three, six, and 24 months, respectively. The reason for discontinuation was lack of efficacy in 78% and adverse events in 22%. Except for higher drug survival in women (odds ratio = 0.51, 95% confidence interval, 0.27 to 0.97), no prognostic factors were found. Adverse events were reported 206 times in 111 patients, the most common being injection site reactions (36%). Serious adverse events occurred in 12% of the patients, with one classified as related.

Conclusions

The short term efficacy and safety profile of anakinra are comparable to those found in randomised clinical studies. However, the drug survival of anakinra after two years is low, mostly because of lack of efficacy.

Keywords: anakinra, rheumatoid arthritis, drug survival

Several new strategies have been developed in the last decade that specifically target cytokines such as tumour necrosis factor α (TNFα) and interleukin 1 (IL1) that are implicated in the inflammation found in rheumatoid arthritis. Anakinra is a recombinant non‐glycosylated form of the human IL1 receptor antagonist which competes for the IL1 receptor with IL1 and thereby prevents IL1 signalling.

Anakinra has been studied in rheumatoid arthritis in five randomised controlled trials.1,2,3,4,5,6 Although its efficacy has been consistently superior to placebo for periods of up to 48 weeks, ACR20% response percentages never exceeded 50%, compared with responses in the placebo group of up to 19%. In addition to this modest effect on disease activity, anakinra has also been shown to have a beneficial effect on radiological damage superior to placebo.4 The safety profile of anakinra is favourable, with adverse event rates comparable to placebo. Injection site reactions are an exception, as over 50% of the patients will develop such reactions, leading to cessation of anakinra in approximately 5%. In addition, while serious adverse event rates are similar to placebo, serious infections seem to occur more often in patients treated with anakinra.3

Although the proof of the principle of IL1 blockade with anakinra in rheumatoid arthritis has been established, no studies have compared this agent with other disease modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs). The combination of anakinra and methotrexate has been shown to be safe, but the use of an add‐on design prevented conclusions being drawn about differences in efficacy.5 A study comparing etanercept monotherapy with the combination of anakinra and etanercept yielded no clinical benefit but resulted in an increased rate of infectious adverse events.7 Interestingly, the publication of the latest large pragmatic trial included only safety data and did not report efficacy data, raising doubt about the efficacy of anakinra in rheumatoid arthritis.4,8 Finally, post‐marketing data on long term efficacy and safety are not yet available (up to May 2005).

We set out to evaluate the efficacy, safety, and drug survival of anakinra in clinical practice.

Methods

All patients with rheumatoid arthritis who started anakinra (100 mg subcutaneously daily) between May 2002 and February 2004 in six Dutch hospitals were included in a two year prospective, and in part retrospective, cohort study. Participating hospitals were one university medical centre, one hospital specialising in rheumatic diseases, and four general hospitals. The patients fulfilled the Dutch criteria for reimbursement of anakinra and anti‐TNF therapy: moderate or high disease activity (28 joint disease activity score (DAS28) >3.2) and treatment failure on methotrexate and one other DMARD. No exclusion criteria were used.

The disease activity was prospectively assessed at baseline and at three months in all patients and after 18 months in a subset of patients using the DAS28 and the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) response criteria 9. Lack of efficacy was defined as DAS28 decrease <1.2 at three months and judged by the treating rheumatologist thereafter. All other data was collected retrospectively by review of the patients' case records, including previous treatments and disease related data, adverse events, the use and change of concomitant drugs, and date treatment with anakinra stopped, and the reason for discontinuation. Safety was evaluated using the common toxicity criteria (CTC).10

Statistical analyses

All analyses (drug survival and efficacy) were based on intention to treat. Drug survival was analysed using Kaplan–Meier survival curves. Termination of treatment because of adverse events and lack of efficacy were taken as end points. For patients who were lost to follow up and for those who were still being treated with anakinra the observation time was censored. Prognostic factors for drug survival (age, sex, weight, rheumatoid factor, concomitant drug treatment, previous anti‐TNFα treatment) were analysed using the Cox proportional hazard model. Analyses employed SPSS statistical software, version 12.1 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Results

One hundred and fifty patients were eligible for evaluation, including 71 with at least 18 months of follow up. A total observation time of 103.5 patient‐years was obtained. In four patients who fulfilled inclusion criteria, no data could be retrieved and these patients were excluded. Baseline characteristics of the patients are shown in table 1. Concomitant drug treatment at baseline and during anakinra included DMARDs (53%; methotrexate 35%) and corticosteroids (46%).

Table 1 Baseline patient characteristics (n = 146).

| Age (years) | 58.2 (12.6) |

| Female (%) | 82 |

| Race, white (%) | 97.3 |

| Disease duration (years)* | 9 (3 to 12) |

| Rheumatoid factor (%) | 69.2 |

| Previous DMARDs * (n) | 4 (3 to 7) |

| Methotrexate dosage (mg/week) | 16.7 (6.1) |

| Previous anti‐TNFα treatment (%) | 38 |

| DAS28 | 6.34 (0.77) |

| VAS general health (mm) | 70.9 (14.1) |

| ESR (mm/hour) | 41.9 (21.1) |

| Swollen joints (n) | 10.8 (4.96) |

| Tender joints (n) | 14.2 (5.96) |

| Hb (mmol/l (mg/dl)) | 7.8 (0.73) (12.6 (1.2)) |

Values are mean (SD) unless stated otherwise.

*Median (25th to 75th centile).

DAS28, 28 joint disease activity score; DMARD, disease modifying antirheumatic drug; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; Hb, haemoglobin; TNF, tumour necrosis factor; VAS, visual analogue scale.

After three months 55% of all patients showed a response; 63 (43%) and 17 (12%) fulfilled criteria for moderate and good response, respectively. Comparable improvement percentages were seen in all individual indices of disease activity, including ESR. Concomitant drug treatment in the first three months was increased, not changed, or decreased in 7%, 85%, and 8% of the patients (corticosteroids), and in 11%, 88%, and 1% of the patients (DMARDs), respectively.

The disease activity after 18 months was measured in 42 of the 71 patients still in the study (eight of 15 still on anakinra, and 34 of 56 switched to other treatments). The DAS28 improvement compared with baseline and the EULAR response percentages were greater in the patients using anakinra than in those who switched to other DMARDs (12%) or anti‐TNFα (88%). The patients who continued to use anakinra did not have significant changes in concomitant DMARD or corticosteroid treatment.

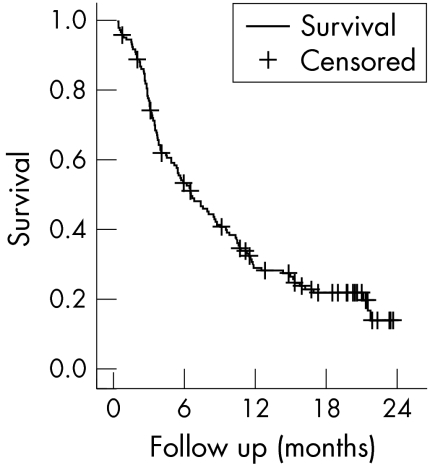

Drug survival was 78%, 54%, 32%, and 14% after three, six, 12, and 24 months, respectively (fig 1). Median drug survival was 209 days (95% confidence interval (CI), 150 to 268). Reasons for discontinuation were lack of efficacy in 78% and adverse events in 22%. Cox proportional hazard analysis revealed no factors associated with better drug survival except for female sex (odds ratio = 0.51 (95% CI, 0.27 to 0.97)). In particular, previous use of anti‐TNF (OR = 0.93 (0.60 to 1.45)) or the number of previous DMARDs (OR = 1.2 (0.83 to 1.51)) were not related to differences in drug survival.

Figure 1 Kaplan–Meier survival analysis for treatment with anakinra.

In all, 206 adverse events were recorded in 111 patients (table 2). The most frequent related adverse events were injection site reactions (36% of the patients). The frequency of injection site reactions was significantly lower in patients who used concomitant prednisone (25% v 46%, p<0.01) but was not associated with concomitant use of DMARDs.

Table 2 Adverse events during anakinra treatment.

| Any adverse event | 111 (75%) |

| Total adverse events* | 206 |

| Mild | 187 |

| Severe | 19 |

| Infection | 1 |

| Death | 3 |

| Malignancy | 3 |

| Other | 12 |

| Common adverse events | |

| Injection site reaction | 53 (36%) |

| Joint pain | 18 (12%) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis exacerbation | 17 (11%) |

| Itching | 8 (5%) |

| Dyspnoea | 7 (5%) |

| Mild infections | 19 (13%) |

Data are n (%) unless otherwise stated.

*Number of adverse events.

Nineteen serious adverse events occurred in 17 patients (12%), with one classified as probably related: an episode of thrombocytopenia, which improved after cessation of anakinra but reoccurred after a rechallenge. This patient had experienced the same side effect on adalimumab. Three malignancies developed during treatment with anakinra: a pleural mesothelioma, a basal cell carcinoma of the skin, and a rectal carcinoma. Three patients died during anakinra treatment because of heart failure and obstructive pulmonary disease (both pre‐existent) and Staphylococcus aureus sepsis, respectively.

Discussion

The short term efficacy and overall safety profile of anakinra in our cohort are comparable with those found in controlled studies. However, long term drug survival is low and this is almost exclusively because of lack of efficacy.

One can speculate whether differences between short and long term clinical efficacy are caused by secondary inefficacy or whether initial improvements overestimate the disease modifying properties of anakinra—other factors could also have contributed to the early clinical response, including regression to the mean in disease activity variables, patients' and physicians' expectation bias, and change in concomitant drug treatment. The latter two do not seem to have played a significant role in the present study (corticosteroids and DMARDs were kept stable in the great majority of patients, and expectation bias would probably have resulted in differences between improvement in subjective variables such as VAS and joint counts and objective variables such as ESR).

Secondary inefficacy could have been caused by formation of neutralising antibodies against anakinra. Recently, a high incidence of antibody formation associated with secondary inefficacy was found in rheumatoid patients treated with infliximab.11,12 This is in contrast to earlier results from sponsor dependent controlled studies, where antibody formation was reported in low frequency, and a relation with efficacy was not seen.13 Although there are currently no data to support this hypothesis, a similar pattern might emerge for anakinra.1

Drug survival is not only a measure of efficacy and toxicity but is also determined by the availability of other treatments. The number of previous DMARDs and previous failure of anti‐TNFα treatment were, however, not associated with better efficacy, which is in line with data found by others.14,15 Thus, the presence or absence of other treatment options did not seem to influence drug survival. The patients who continue using anakinra seemed to have a sustained clinical benefit and did not seem to continue its use because of lack of other treatment options. Although data on disease activity were only available on a subset of patients, the improvement in patients still using anakinra was comparable with those switching to other treatments, mainly TNFα blocking agents.

The efficacy and drug survival of anakinra do not compare favourably with other antirheumatic drugs. Short term response percentages are not in the same range as those found after treatment with anti‐TNFα.16 The two year drug survival of anakinra is also substantially lower than for other DMARDs. For methotrexate, reported two year drug survival ranges from 60% to 85% and for TNFα blocking agents, drug survival reaches nearly 60% in our population,17 and even higher in other studies.18 We were not able to identify factors that are associated with better drug survival, except for the lower dropout rate in women.

Our data confirm the favourable safety profile of anakinra. No unusual number of malignancies was found and serious infections rates were lower than reported earlier (0.7% v 2%).5 Interestingly, concomitant use of corticosteroids was associated with fewer injection site reactions, although this was not reflected in higher drug survival. It should be noted, though, that a complete collection and classification of all adverse events is more challenging in a retrospective setting because of report bias, although this effect should have less influence on collection of serious adverse events. Also, longer exposure times may be needed to witness an increase in the development of malignancies.

In conclusion, the short term efficacy and overall safety profile of anakinra seen in clinical practice are comparable to those found in randomised clinical trials. However, the two year drug survival of this agent is low, mostly because of lack of efficacy. A subset of patients showed a sustained response comparable to that with TNFα blocking agents. When anakinra is used, corticosteroids may be added to decrease the chance of injection site reactions.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr Siewertsz van Reesema, I Nuver‐Zwart, M Janssen, J Stolk, E Knijff, and PLCM van Riel.

Abbreviations

ACR - American College of Rheumatology

CTC - common toxicity criteria

DAS28 - 28 joint disease activity score

DMARD - disease modifying antirheumatic drug

EULAR - European League Against Rheumatism

References

- 1.Campion G V, Lebsack M E, Lookabaugh J, Gordon G, Catalano M. Dose‐range and dose‐frequency study of recombinant human interleukin‐1 receptor antagonist in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1996391092–1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nuki G, Breshnihan B, Moraye B B, McCabe D. Long‐term safety and maintenance of clinical improvement following treatment with anakinra (recombinant human interleukin‐1 receptor antagonist) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2002462838–2846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fleischmann R M, Schechtsman J, Bennett R, Handel M L, Burmester G R, Tesser J.et al Anakinra, a recombinant human interleukin‐1 antagonist (r‐metHuIL‐1ra), in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 200348927–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schiff M H, DiVittorio G, Tesser J, Fleischmann R, Schechtman J, Hartman S.et al The safety of anakinra in high‐risk patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: six‐month observations of patients with comorbid conditions. Arthritis Rheum 2004501752–1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen S, Hurd E, Cush J, Schiff M, Weinblatt M E, Moreland L W.et al Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with anakinra, a recombinant human interleukin‐1 receptor antagonist, in combination with methotrexate: results of a twenty‐four‐week, multicenter, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 200246614–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen S B, Moreland L W, Cush J J, Greenwald M W, Block S, Shergy W J.et al A multicentre, double blind, randomised, placebo controlled trial of anakinra (Kineret), a recombinant interleukin 1 receptor antagonist, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with background methotrexate. Ann Rheum Dis 2004631062–1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gebovese M C, Cohen S B, Moreland L, Lium D, Robbins S, Newmark R.et al Combination therapy with etanercept and anakinra in the treatment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis who have been treated unsuccessfully with methotrexate. Arthritis Rheum 2004501412–1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burls A, Jobanputra P. The trials of anakinra. Lancet 2004364827–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Gestel A M, Prevoo M L L, van ‘t Hof M A, van Rijswijk M H, van de Putte L B A, van Riel P L C M. Development and validation of the European league against rheumatism response criteria for rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 19963934–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program Revised 23 March 1998. Common toxicity criteria, version 2.0. DCTD, NCI, NIH, DHHS, March 1998

- 11.Eriksson C, Engstrand S, Sundqvist K G, Rantapaa‐Dahlqvist S. Autoantibody formation in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with anti‐TNF‐alpha therapy. Ann Rheum Dis 200564403–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolbink G J, Voskuyl A, Lems W, de Groot E, Nurmohamed M T, Tak P P.et al Relationship between serum trough infliximab levels, pretreatment C reactive protein levels, and clinical response to infliximab treatment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 200564704–707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maini R N, Breedveld F C, Kalden J R, Smolen J S, Davis D, Macfarlane J D. Therapeutic efficacy of multiple intravenous infusions of anti‐tumor necrosis factor alpha monoclonal antibody combined with low‐dose weekly methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1998411552–1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buch M H, Bingham S J, Yohei S, McGonagle D, Bejarano V, White J.et al Lack of response to anakinra in rheumatoid arthritis following failure of tumor necrosis factor α (alfa) blockade. Arthritis Rheum 200450725–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Langer H E, Missler‐Karger B. Kineret: efficacy and safety in daily clinical practice: an interim analysis of the Kineret response assessment initiative (kreative) protocol. Int J Clin Pharmacol Res 200323119–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nancy J Olsen, C Michael Stein New Drugs for Rheumatoid Arthritis. N Engl J Med 20003502167–2179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flendrie M, Creemers M C, Welsing P M, den Broeder A A, van Riel P L. Drug‐survival during treatment with tumour necrosis factor blocking agents in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 200362(suppl 2)ii30–ii33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geborek P, Crnkic M, Petersson I F, Saxne T. South Swedish Arthritis Treatment Group. Etanercept, infliximab, and leflunomide in established rheumatoid arthritis: clinical experience using a structured follow up program in southern Sweden, Ann Rheum Dis 200261793–798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]