Abstract

The usefulness of single-enzyme amplified-fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) analysis for the subtyping of Mycobacterium kansasii type I isolates was evaluated. This simplified technique classified 253 type I strains into 12 distinct clusters. The discriminating power of this technique was high, and the technique easily distinguished between the epidemiologically unrelated control strains and our clinical isolates. Overall, the technique was relatively rapid and technically simple, yet it gave reproducible and discriminatory results. This technique provides a powerful typing tool which may be helpful in solving many questions concerning the reservoirs, pathogenicities, and modes of transmission of these isolates.

Mycobacterium kansasii is the most common cause of pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial infection in the non-human immunodeficiency virus-infected population in many parts of the world (4, 6, 9, 12, 16, 19, 25). Of all nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases, the clinical course of M. kansasii lung disease most closely parallels that caused by M. tuberculosis infection (12, 36). Although it has seldom been recovered from soil (10, 22), M. kansasii has frequently been isolated from tap water and is thought to be acquired from the environment rather than by case-to-case transmission (8, 17, 18, 20, 24, 29, 31, 37).

The first typing method developed for M. kansasii was phage typing. Other features, especially catalase activity, have been used to type M. kansasii isolates. Isolates with high catalase activities were considered more virulent (23). Analysis of the 16S rRNA sequence (27), amplification of the 16S-23S rRNA spacer region (1), PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis of the hsp65 gene (7, 33), and detection of insertion sequence element IS1652 (38) showed that M. kansasii contains a subspecies genetically distinct from the typical M. kansasii isolates.

M. kansasii has been classified into five subspecies or types (types I to V) on the basis of PCR-RFLP analysis of the hsp65 gene (7, 33). These results have been confirmed by differences in the sequences of the 16S-23S rRNA spacer region (2) and by RFLP analysis with the major polymorphic tandem repeat probe (23). Recently, two new types (types VI and VII) have been described (26, 32). Of the seven types identified, M. kansasii type I is the most prevalent type from human sources worldwide. Moreover, large restriction fragment-pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (LRF-PFGE) (2, 14, 23), amplified-fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) analysis (23), and randomly amplified polymorphic DNA analysis (2) have produced polymorphic patterns within each type.

By use of these typing methods, minimal genetic polymorphism was noted among type I strains. These results gave the impression that type I shows substantial clonality (21). This apparent clonality may have resulted from the insufficient discriminatory powers of the techniques used. Solutions to questions about the reservoirs, pathogenicities, and modes of transmission of these isolates require more discriminating typing techniques in order to shed light on possible heterogeneity. In the present report we describe a simplified typing approach which may be a valuable addition to the existing genotyping fingerprinting methods available for M. kansasii.

Next to LRF-PFGE, whole-genome fingerprinting by the AFLP technique is one of the most promising methods for the typing of bacterial pathogens (13). The AFLP technique is based on the selective PCR amplification of restriction fragments from a digest of total genomic DNA and can be used for DNA of any origin or complexity. Fingerprints are produced without prior knowledge of the sequence and with a limited set of primers. In the classic AFLP analysis, the genomic DNA is digested with two restriction enzymes and two double-stranded oligonucleotide adapters are ligated to the restriction fragments. The adapter-tagged fragments are then subjected to PCR amplification with radioactively labeled primers, and the PCR products are analyzed by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (35). For the purpose of bacterial strain typing, major applications of AFLP analysis have been reported with the genera Aeromonas, Acinetobacter, Campylobacter, Legionella, Staphylococcus, and Streptococcus (for reviews, see references 3 and 28). Problems due to the use of radioactively labeled primers led to the development of fluorescently labeled primers, which permitted the detection of fragments in an automatic sequencer apparatus. While the fluorescent format has significant advantages, the cost of a DNA sequencer may be prohibitive for most laboratories. A number of modified AFLP analysis-based techniques have been described. One of these alternative procedures is based on the use of a single enzyme, a single adapter, a single unlabeled primer, and analysis by agarose gel electrophoresis (11, 34). This simplified AFLP method presents several advantages compared to the classic AFLP analysis. It allows the detection of RFLPs directly on agarose gels without the need to use labeled primers and the tedious analysis of complicated polyacrylamide gels.

The present study describes the potential usefulness of a single-enzyme AFLP method for the differentiation of M. kansasii isolates at the subspecies level. The steps of the AFLP procedures used here are (i) digestion of the extracted DNA with a single enzyme with an average cutting frequency, (ii) ligation of an adapter to each end of the digestion fragments, (iii) selective PCR amplification of the adapter-tagged fragments with a single unlabeled adapter-specific primer that has an extension of one selective base at the 3′ end, and (iv) electrophoretic separation on an agarose gel and detection of the amplified fragments by ethidium bromide staining.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

A total of 255 M. kansasii strains were included in this study: 252 clinical isolates and 3 epidemiologically unrelated strains. The clinical strains were recovered from 240 patients: (i) 228 single patient isolates and (ii) 24 paired isolates collected from 12 patients at different intervals. These isolates were included to assess the reproducibilities of the AFLP patterns. All the clinical isolates were recovered from five public hospitals in the district of Bizkaia in Spain between 1995 and 2002. The epidemiologically unrelated strains included (i) type strain CECT 3030 (kindly provided by La Colección Española de Cultivo Tipo [CECT], Valencia, Spain), a subculture of type strain ATCC 12478; (ii) a strain of subspecies I (strain PI) kindly provided by Veronique Vincent (National Reference Center for Mycobacteria, Pasteur Institute, Paris, France); and (iii) a scotochromogenic mutant strain (strain BI), which was recovered from an old archived clinical isolate recovered from a patient with pulmonary infection in 1993. All clinical isolates were identified by conventional biochemical tests and by the AccuProbe test (Gen-Probe Inc.).

DNA extraction.

Whole-genome DNA was prepared by the standardized extraction method described previously (30). Some colonies from Löwenstein-Jensen medium were harvested, placed into 400 μl of Tris-EDTA (pH 8.0) buffer, and inactivated by heating at 80°C for 20 min. Lysozyme was added at a concentration of 1 mg/ml, and the tubes were incubated overnight at 37°C to digest the mycobacterial cell wall. After the addition of proteinase K (to 0.1 mg/ml) and sodium dodecyl sulfate (to 1%), the tubes were incubated at 65°C for 20 min. NaCl (0.6 M) and N-cetyl-N,N,N-trimethyl ammonium bromide were added, and the tubes were incubated again at 65°C for 10 min. Subsequent to extraction with chloroform-isoamyl alcohol, DNA was precipitated with isopropanol and washed with 70% cold ethanol. The extracted DNA was resolved in 50 μl of TE buffer (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]).

PCR-RFLP analysis of hsp65 gene.

PCR-RFLP analysis of the hsp65 gene was performed for all strains as described previously (7, 33). A 439-bp segment amplified by using primers Tb11 (5′-ACC AAC GAT GGT GTG TCC AT) and Tb12 (5′-CTT GTC GAA CCG CAT ACC CT) was digested with BstEII and HaeIII (Roche). Restriction fragments were then separated by electrophoresis on a 3% MS-8 agarose gel (Pronadisa) and visualized by staining with ethidium bromide and UV light.

AFLP analysis. (i) Preparation of tagged DNA fragments.

A 6-μl aliquot of DNA was digested for 90 to 120 min at 30°C with 20 U of the ApaI enzyme (Roche) in a final volume of 20 μl of the buffer provided with the enzyme. A 10-μl aliquot of digested DNA was used in a ligation reaction mixture containing 0.2 μg of the double-stranded adapter and 1 U of T4 DNA ligase (Roche) in a final volume of 20 μl of single-strength ligase buffer, and the mixture was held at 37°C for 90 to 120 min. To prepare the adapters, oligonucleotides Apa-1 and Apa-2 were mixed in equal molar amounts in 1× PCR buffer (Roche) and were allowed to anneal as the mixture cooled from 80 to 4°C (1°C each min) in a thermocycler. After ligation, the ligated DNA samples were diluted with distilled water to a final volume of 55 μl and were then heated to 65°C for 10 min to inactivate the T4 ligase. A 5-μl aliquot of the diluted sample was used as a template for PCR.

(ii) PCR of tagged DNA.

Amplification reactions were performed in a final volume of 50 μl containing 5 μl of the tagged DNA, 10% glycerol (Sigma), 1.25 U of Taq polymerase (Roche), 250 μM (each) deoxynucleoside triphosphate (Promega), and a single primer at a concentration of 1 μM in 1× PCR buffer (1.5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.3]) provided by the manufacturer. Amplification was performed in a GeneAmp PCR System 2400 (Perkin-Elmer). After initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min, the reaction mixture was run through 33 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 60 s, annealing at 60°C for 60 s, and extension at 72°C for 150 s, followed by a final extension period at 72°C for 5 min. The oligonucleotides used in this study are listed in Table 1. The amplified fragments were separated by electrophoresis at 3.5 V/cm in a 2% (wt/vol) MS-8 agarose gel (Pronadisa) in 1× TBE buffer (90 mM Tris, 90 mM boric acid, 2 mM EDTA) and were stained with ethidium bromide (0.5 μg/ml). The gels were photographed under UV illumination. The DNA VIII molecular weight marker (Roche) was used.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotide sequences used in this studya

| Oligonucleotide | Sequenceb |

|---|---|

| Apa-1 | 5′-TCG TAG ACT GCG TAC AGG CC-3′ |

| Apa-2 | 5′-TGT ACG CAG TCT AC-3′ |

| Apa-A | 5′-GAC TGC GTA CAG GCC CA-3′ |

| Apa-C | 5′-GAC TGC GTA CAG GCC CC-3′ |

| Apa-G | 5′-GAC TGC GTA CAG GCC CG-3′ |

| Apa-T | 5′-GAC TGC GTA CAG GCC CT-3′ |

The oligonucleotides were described previously (15).

The selective base is underlined.

RESULTS

PCR-RFLP analysis.

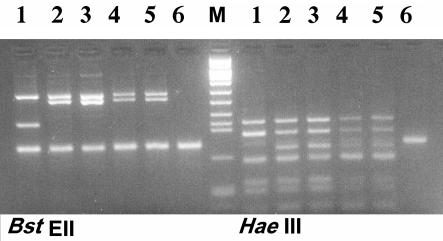

Hsp65 PCR-RFLP analysis generated two patterns among the 255 M. kansasii strains tested. A total of 250 clinical isolates and the 3 epidemiologically unrelated strains (the type strain and strains PI and BI) presented the type I pattern. Only two clinical isolates presented the type II pattern (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

PCR-RFLP analysis of the hsp65 gene after digestion with BstEII and HaeIII of representative strains. Lanes 1, type II; lanes 2 to 5, type I; lanes 6, negative controls; lane M, molecular size marker VIII.

AFLP analysis.

The initial studies were performed to develop optimal conditions for the performance of the AFLP analysis. In this part of the study, a small number of strains (including the epidemiologically unrelated control strains and some clinical strains isolated from different hospitals and at different times) were analyzed. Of the five primers used for PCR amplification, primers Apa-1 and Apa-G produced numerous bands that ran as a smear on the gel. However, the selective primers, primers Apa-A, Apa-C, and Apa-T, generated the best amplification patterns for ease of visual analysis and strain identification. These three primers were used thereafter in the following analysis.

The type II strains generated the same patterns with each of these three primers. These patterns were not generated by any of the type I strains. The patterns generated by type I strains were polymorphic.

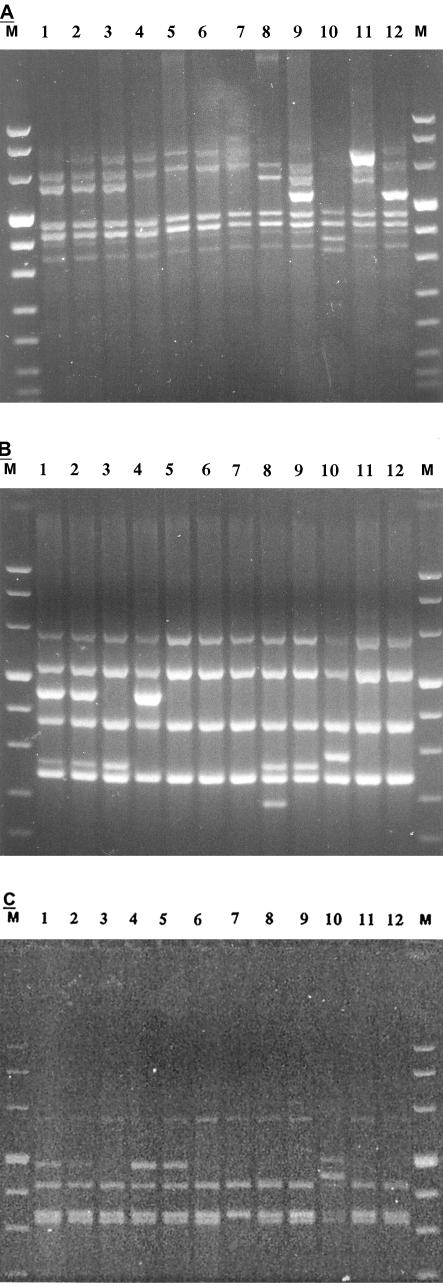

The patterns generated with primer Apa-A were composed of four to seven bands ranging in size between 340 and 850 bp (Fig. 2A). Primer Apa-A generated seven different patterns, which were numbered 1 through 7. Pattern 1 was the most prevalent one (n = 183), followed by pattern 2 (n = 65). Patterns 3 to 7 were unique, and each one was represented by only one strain: patterns 3 and 4 were each produced by only one clinical isolate, pattern 5 was produced by scotochromogenic strain BI, pattern 6 was produced by strain PI, and pattern 7 was produced by type strain CECT 3030.

FIG. 2.

AFLP banding patterns produced for 12 representative strains from clusters 111 to 762. The analysis was performed with three different selective primers: Apa-A (A), Apa-C (B), and Apa-T (C).Lanes M, molecular size markers VIII (Roche); lanes 1, cluster 111; lanes 2, cluster 112; lanes 3, cluster 122; lanes 4, cluster 211; lanes 5, cluster 221; lanes 6, cluster 222; lanes 7, cluster 223; lanes 8, cluster 332; lanes 9, cluster 422; lanes 10, cluster 544; lanes 11, cluster 652; lanes 12, cluster 762.

The patterns generated by primer Apa-C were composed of four to six bands ranging in size between 225 and 650 bp (Fig. 2B). Primer Apa-C generated six patterns, which were numbered 1 through 6. Pattern 2 was the most prevalent one (n = 186), followed by pattern 1 (n = 63). Patterns 3 to 6 were unique, and each one was represented by only one strain: pattern 3 was produced by only one clinical strain, pattern 4 was produced by strain BI, pattern 5 was produced by strain PI, and pattern 6 was produced by the type strain.

The patterns generated with primer Apa-T were composed of three to five bands ranging in size between 335 and 635 bp (Fig. 2C). Primer Apa-T generated only four patterns, which were numbered 1 through 4. Pattern 2 was the most prevalent (n = 179), followed by pattern 1 (n = 72). Pattern 3 was produced by only one clinical strain. Pattern 4 was produced by strain BI. Pattern 2 was produced by strain PI and by the type strain.

By using the patterns generated by the three primers for the clustering of type I strains, 12 clusters were identified. Throughout the text these clusters are indicated with a numeric notation corresponding to the patterns generated by these three primers. Each cluster is indicated with three digits (the first digit for the Apa-A pattern, the second one for the Apa-C pattern, and the third one for the Apa-T pattern). For example, cluster 221 means that strains of this clusters produced pattern 2 with primer Apa-A, pattern 2 with primer Apa-C, and pattern 1 with primer Apa-T. Figure 2A to C show the AFLP patterns for a representative strain of each cluster. Cluster 122 was the most prevalent (n = 121), followed by cluster 111 (n = 59) and cluster 222 (n = 51). Cluster 221 contained 12 strains, and cluster 112 contained only 3 strains. Clusters 211, 223, 332, and 422 each included only one clinical strain. Cluster 544 was formed by scotochromogenic strain (strain BI). Cluster 652 contained strain PI. Cluster 762 contained the type strain.

The reproducibilities of the AFLP patterns were assessed by including 24 paired strains collected from 12 patients at different intervals. The reproducibilities were also confirmed by repeated testing with independent DNA preparations. Typing of the control strains and many clinical strains was repeated more than five times. Similar patterns were repeatedly obtained from each strain. However, slight variations were observed in only faint large-molecular-size bands (larger than 900 bp), and to avoid confusion, these fragments were disregarded. The AFLP patterns were stable for the control strains and for many clinical strains after five successive subcultures over a period of 4 months.

DISCUSSION

In the present study the vast majority of the clinical isolates (250 of 252 isolates), collected in Bilbao, Spain, were of type I. This result is nearly similar to that reported by Alcaide et al. (2). In their study the 51 clinical isolates collected from Barcelona, Spain, were of type I. Type II was absent from the Spanish collection.

In our study, the enzyme ApaI was chosen for AFLP template preparation on the basis of the theoretical assumption that it cleaves the genomes of organisms with high G+C contents, such as M. kansasii (G+C content, 64%), at relatively high frequencies (5, 15).

While the number of patterns generated by a single primer was relatively low (seven patterns with primer Apa-A, six patterns with primer Apa-C, and four patterns with primer Apa-T), the discriminatory power of the technique was markedly augmented by using the patterns produced by the three primers for clustering, which produced 12 different clusters. Moreover, the described numeric notation gives a rough idea of strain-to-strain relatedness. For example, cluster 122 is comparatively more related to cluster 222 than to cluster 111 but is completely different from cluster 544. The reproducibility of the AFLP method was good throughout the entire investigation, and the patterns were stable after more than five successive subcultures over a period of 4 months.

In a previous study, Picardeau et al. (23) reported the use of a single-enzyme AFLP analysis with the enzyme PstI for the differentiation of strains within each one of the five types identified. The patterns for the type I strains were very similar or even identical, and only a few strains presented patterns different from those shared by most strains. In the same study and by using LRF-PFGE, the 24 strains of type I generated only four patterns with the enzyme DraI. Moreover, three strains (one of which was of type I) were untypeable by LRF-PFGE and yielded degraded DNA.

Similarly, Alcaide et al. (2) previously used LRF-PFGE to study the relatedness among M. kansasii type I strains. Minimal genetic polymorphism was noted among 111 strains, which were distributed among only five patterns representing minor differences.

The apparent clonality of M. kansasii type I seen in these studies may have resulted from the insufficient discriminatory powers of the techniques used.

Further studies should take into consideration the possible high degree of heterogeneity of M. kansasii type I isolates. The use of powerful typing techniques or a combination of techniques will bring to light this heterogeneity and will help investigators answer many questions about the natural reservoirs, the modes of transmission, and the possibility of human-to-human transmission of M. kansasii type I.

In conclusion, the present investigation has demonstrated the usefulness of the simplified single-enzyme AFLP technique as a reliable typing tool for the differentiation of M. kansasii type I isolates. Further studies are needed to validate its potential for the fingerprinting of other M. kansasii types, however. AFLP analysis demonstrated high levels of variation among type I isolates and is therefore a valuable addition to the existing available genotyping methods for the fingerprinting of M. kansasii.

Acknowledgments

We thank Veronique Vincent and Cristina Gutiérrez, National Reference Center for Mycobacteria, Pasteur Institute, for providing some of the strains used in this study and for scientific discussion.

This work was supported by research project grant 01/0143-FIS from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid, Spain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abed, Y., C. Bollet, and P. De Micco. 1995. Identification and strain differentiation of Mycobacterium species on the basis of DNA 16S-23S spacer region polymorphism. Res. Microbiol. 146:405-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alcaide, F., I. Richter, C. Bernasconi, B. Springer, C. Hagenau, R. S. Röbbecke, E. Tortoli, R. Martín, E. C. Böttger, and A. Telenti. 1997. Heterogeneity and clonality among isolates of Mycobacterium kansasii: implications for epidemiological and pathological studies. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:1959-1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blears, M. J., S. A. de Grandis, H. Lee, and J. T. Trevors. 1998. Amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP): a review of the procedure and its applications. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biot. 21:99-114. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bloch, K. C., L. Zwerling, M. J. Pletcher, J. A. Hahn, J. L. Gerberding, S. M. Ostroff, D. J. Vugia, and A. L. Reingold. 1998. Incidence and clinical implication of isolation of Mycobacterium kansasii: results of a 5-year, population-based study. Ann. Intern. Med. 129:698-704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clark-Curtiss, J. E. 1990. Genome structure of mycobacteria, p. 77-96. In J. McFadden (ed.), Molecular biology of mycobacteria. Surrey University Press, London, United Kingdom.

- 6.Corbett, E. L., M. Hay, G. J. Churchyard, P. Herselman, T. Clayton, B. G. Williams, R. Hayes, D. Mulder, and K. M. De Cock. 1999. Mycobacterium kansasii and M. scrofulaceum isolates from HIV-negative South African gold miners: incidence, clinical significance and radiology. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 3:501-507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Devallois, A., K. S. Goh, and N. Rastogi. 1997. Rapid identification of mycobacteria to species level by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of the hsp65 gene and proposition of an algorithm to differentiate 34 mycobacterial species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:2969-2973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engel, H. W. B., and L. G. Berwald. 1980. The occurrence of Mycobacterium kansasii in tapwater. Tubercle 61:21-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evans, S. A., A. Colville, A. J. Evans, A. J. Crisp, and I. D. A. Jonhnston. 1996. Pulmonary Mycobacterium kansasii infection: comparison of the clinical features, treatment and outcome with pulmonary tuberculosis. Thorax 51:1248-1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Falkinham, J. O., III. 1996. Epidemiology of infection by nontuberculous mycobacteria. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 9:177-215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gibson, J. R., E. Slater, J. Xerry, D. S. Tompkins, and R. J. Owen. 1998. Use of an amplified-fragment length polymorphism technique to fingerprint and differentiate isolates of Helicobacter pylori. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:2580-2585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Griffith, D. E. 2002. Management of disease due to Mycobacterium kansasii. Clin. Chest Med. 23:613-621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huys, G., L. Rigouts, K. Chemlal, F. Portaels, and J. Swings. 2000. Evaluation of amplified fragment length polymorphism analysis for inter- and intraspecific differentiation of Mycobacterium bovis, M. tuberculosis, and M. ulcerans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:3675-3680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iinuma, Y., S. Ichiyama, Y. Hasegawa, K. Shimokata, S. Kawahara, and T. Matsushima. 1997. Large-restriction-fragment analysis of Mycobacterium kansasii genomic DNA and its application in molecular typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:596-599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Janssen, P., R. Coopman, G. Huys, J. Swings, M. Bleeker, P. Vos, M. Zabeau, and K. Kersters. 1996. Evaluation of the DNA fingerprinting method AFLP as a new tool in bacterial taxonomy. Microbiology 142:1881-1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaustová, J., M. Chmelík, D. Ettlová, V. Hudec, H. Lazarová, and S. Richtrová. 1995. Disease due to Mycobacterium kansasii in the Czech Republic: 1984-1989. Tubercle Lung Dis. 76:205-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaustová, J., Ž. Olšovský, M. Kubín, O. Zatloukal, M. Pelikán, and V. Hradil. 1981. Endemic occurrence of Mycobacterium kansasii in water-supply systems. J. Hyg. Epidemiol. Microbiol. Immunol. 25:24-30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kubica, G. P., A. J. Kaufmann, and W. E. Dye. 1970. The isolation of high-catalase Mycobacterium kansasii from tap water. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 101:430-431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lillo, M., S. Orengo, P. Cenoch, and R. L. Harris. 1990. Pulmonary and disseminated infection due to Mycobacterium kansasii: a decade of experience. Rev. Infect. Dis. 12:760-767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maniar, A. C., and L. R. Vanbuckenhout. 1976. Mycobacterium kansasii from an environmental source. Can. J. Public Health 67:59-61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McGarvey, J., and L. E. Bermudez. 2002. Pathogenesis of nontuberculous mycobacteria infections. Clin. Chest Med. 23:569-583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oriani, D. S., and M. A. Sagardoy. 2002. Nontuberculous mycobacteria in soils of La Pampa province (Argentina). Rev. Argent. Microbiol. 34:132-137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Picardeau, M., G. Prod'Hom, L. Raskine, M. P. LePennec, and V. Vincent. 1997. Genotypic characterization of five subspecies of Mycobacterium kansasii. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:25-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Powell, B. L., and J. E. Steadham. 1981. Improved technique for isolation of Mycobacterium kansasii from water. J. Clin. Microbiol. 13:969-975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reparas, J. 1999. Enfermedad por Mycobacterium kansasii. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 17:85-90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richter, E., S. Niemann, S. R. Gerdes, and S. Hoffner. 1999. Identification of Mycobacterium kansasii by using a DNA probe (AccuProbe) and molecular techniques. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:964-970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ross, B., K. Jackson, M. Yang, A. Sievers, and B. Dwyer. 1992. Identification of genetically distinct subspecies of Mycobacterium kansasii. J. Clin. Microbiol. 30:2930-2933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Savelkoul, P. H. M., H. J. M. Aarts, J. De Haas, L. Dijkshoorn, B. Duim, M. Otsen, J. L. W. Rademaker, L. Schouls, and J. A. Lenstra. 1999. Amplified-fragment length polymorphism analysis: the state of an art. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:3083-3091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Šlosárek, M., M. Kubín, and J. Pokorný. 1994. Water as a possible factor of transmission in mycobacterial infections. Cent. Eur. J. Public Health 2:103-105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soolingen, D. V., P. E. W. de Hass, and K. Kermer. 2001. Restriction fragment length polymorphism typing of mycobacteria. Methods Mol. Med. 54:165-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steadham, J. E. 1980. High-catalase strains of Mycobacterium kansasii isolated from water in Texas. J. Clin. Microbiol. 11:496-498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taillard, C., G. Greub, R. Weber, G. E. Pfyffer, T. Bodmer, S. Zimmerli, R. Frei, S. Bassetti, P. Rohner, J.-C. Piffaretti, E. Bernasconi, J. Bille, A. Telenti, and G. Prod'hom. 2003. Clinical implications of Mycobacterium kansasii species heterogeneity: Swiss national survey. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:1240-1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Telenti, A., F. Marches, M. Balz, F. Bally, E. C. Böttger, and T. Bodmer. 1993. Rapid identification of mycobacteria to species level by polymerase chain reaction and restriction enzyme analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:175-178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Valsangiacomo, C., F. Baggi, V. Gaia, T. Balmelli, R. A. Peduzzi, and J.-C. Piffaretti. 1995. Use of amplified fragment length polymorphism in molecular typing of Legionella pneumophila and application to epidemiological studies. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:1716-1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vos, P., R. Hogers, M. Bleeker, M. Reijans, T. V. de Lee, M. Hornes, A. Frijters, J. Pot, J. Peleman, M. Kuiper, and M. Zabeau. 1995. AFLP: a new technique for DNA fingerprinting. Nucleic Acids Res. 23:4407-4414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wallace, R. J., J. Glassroth, D. E. Griffith, K. N. Oliver, J. L. Cook, and F. Gordin. 1997. Diagnosis and treatment of disease caused by nontuberculous mycobacteria. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 156:S1-S25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wright, E. P., C. H. Collins, and M. D. Yates. 1985. Mycobacterium xenopi and Mycobacterium kansasii in a hospital water supply. J. Hosp. Infect. 6:175-178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang, M., B. C. Ross, and B. Dwyer. 1993. Identification of an insertion sequence-like element in a subspecies of Mycobacterium kansasii. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:2074-2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]