Abstract

Objective

To characterise temporal trends and factors associated with the prescription of disease modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) at the initial consultation in early rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Methods

Data from 2584 patients with early RA at 19 hospitals were extracted from the Swedish Rheumatoid Arthritis Register for the period 1997–2001. Disease characteristics and DMARD prescription at first consultation with the rheumatologist were investigated using cross tabulation and logistic regression.

Results

DMARD prescriptions, particularly for methotrexate, increased from 1997 to 2001 independently of patient characteristics. Stratification by hospital type showed that patients in district hospitals were less likely to be prescribed DMARDs than those in university hospitals (adjusted odds ratio (OR) = 0.53 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.40 to 0.69), p<0.001), independently of confounding factors. Association of the DAS28 with the likelihood of DMARD prescription was greater among patients attending district hospitals (OR = 1.65 (1.34 to 2.02), p<0.001) than those at university hospitals (OR = 1.23 (1.07 to 1.41), p = 0.003) and county hospitals (OR = 1.34 (1.01 to 1.63), p = 0.003). Interaction testing indicated that the difference was significant (p = 0.007).

Conclusions

Temporal trends in DMARD prescription indicate an increasingly aggressive approach to disease management among Swedish rheumatologists. However, the association of hospital type with DMARD prescription suggests that the adoption of research findings in clinical care varies considerably.

Keywords: early rheumatoid arthritis, disease modifying antirheumatic drug, temporal trends, register

Although research findings support early and aggressive intervention with disease modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA),1,2,3,4 the integration of these findings into daily clinical practice varies considerably, as reflected in rheumatologists' prescribing habits.5,6,7,8 In this study we use clinical data from the initial consultation of patients with early RA with rheumatologists to identify temporal trends and to characterise factors associated with the prescription of DMARD.

Patients and methods

Study population

Data were provided by the Swedish Rheumatoid Arthritis Register, a national quality register for early RA, containing clinical data from initial and follow up consultations. Patients over 15 years of age with RA according to the American College of Rheumatology criteria9 and disease duration of less than 1 year qualify as having early RA. Baseline assessments include name, age, sex, symptom onset, and rheumatoid factor (RF) status using local agglutination methods. Each patient is assigned a code number to enable data extraction without disclosing patient identity. Patients give informed consent before inclusion and are free to withdraw from participation in the register at any time. Ethical clearance for the study was obtained from the Karolinska Institute's Research Ethics Committee in Stockholm.

At the first consultation and follow up assessments, the American College of Rheumatology core set of outcomes are compiled and recorded.10 First consultation defined here includes test results, diagnosis, and prescription of treatment in the weeks immediately after the first visit to the clinic. Patients' pain and general health are quantified on a visual analogue scale (100 mm), and disability is measured by the Swedish version of the Stanford Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ).11 Rheumatologists record the following: physician's global assessment of disease activity using a Likert scale (none, low, medium, high, maximal); intended prescriptions for DMARDs, corticosteroids, non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and analgesics; C reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rates; and the 28 joint count Disease Activity Score for swelling and tenderness (DAS28).12 Disease activity as measured by the DAS2813 is calculated automatically in the database.

All patients with newly diagnosed RA (n = 2584—799 men, 1785 women) from 19 hospitals that contributed data to the Swedish RA Register for the entire 5 year period, 1997–2001, were analysed. Patients with suspected RA are referred from primary care to rheumatology specialist care. Of the 19 hospitals in this study, eight were university teaching hospitals, six were county, and five were district hospitals.

Statistical analysis

Cross tabulation was used to compare the following characteristics by sex for each of the 5 years: age group, RF, disability (HAQ), and disease duration. Mean values for the DAS28 were compared by sex and year using analysis of variance. The associations of DMARD prescription with age, sex, RF, disease duration, type of hospital attended, and the year of diagnosis were analysed using logistic regression. Prescription patterns for glucocorticosteroids (GCs) were also examined. Simultaneous adjustment was made for all these variables and for the DAS28. The material was then stratified by hospital type and analysed similarly. Logistic regression was used to investigate the interaction of hospital type and the DAS28 for the prescription of DMARDs, with adjustment being made for all confounding factors and for the main effects.

In the adjusted model, all variables, except the DAS28, were modelled as a series of binary dummy variables. The DAS28 was modelled as a continuous measure, such that the odds ratio (OR) refers to the change in the probability of DMARD prescription for each one‐unit increase in the DAS28. Patients with at least one missing variable (n = 259) were excluded from this analysis. Univariate analysis was used to evaluate the potential confounding effect of the missing data. The unadjusted and adjusted ORs were calculated with the 95% confidence interval (CI). SPSS was used to analyse the data.14

Results

Patient characteristics

Patients' age, sex, DAS28, HAQ, RF serology, and mean disease duration (6 months) were similar for each of the 5 years and between hospital types. Median HAQ (range) was 1.00 (0–3) for women, 0.88 (0–3) for men and median age was 57 (16–88) years and 63 (18–89) years for women and men, respectively. Mean DAS28 (standard deviation) at inclusion was 5.13 (1.25) for women and 5.07 (1.33) for men.

DMARD prescription patterns

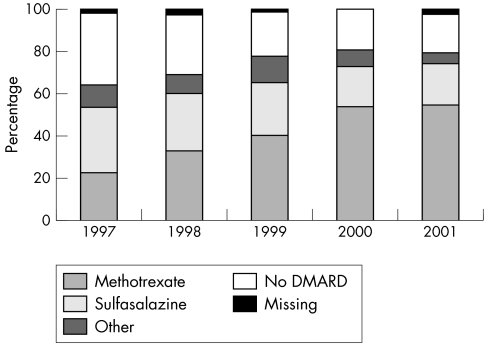

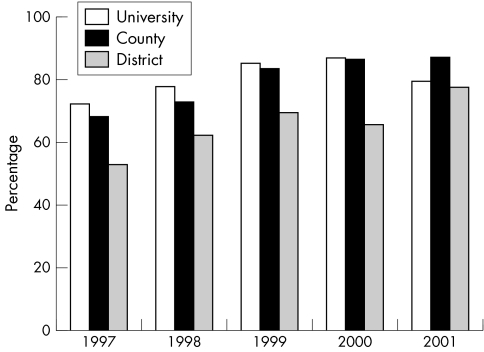

Overall, the proportion of patients prescribed DMARDs—in particular, methotrexate—at the first consultation increased between 1997 and 2001 (fig 1), producing an adjusted OR of 0.43, (95% CI 0.34 to 0.54), p<0.001, but with some variation by hospital type (fig 2). Combinations of DMARDs were prescribed to 31 patients.

Figure 1 Changing preferences in the type of DMARD prescribed at first consultation in early RA, 1997–2001.

Figure 2 Variation between hospital types in the proportion of patients with early RA to be prescribed a DMARD at first consultation, 1997–2001.

Differences in routines for the registration of methotrexate may have confounded these results. If patients were asked to wait for the start of treatment until chest x ray results were known, registration might have been delayed until the first follow up visit. Therefore, we chose to analyse the data again to include methotrexate registered for the first time at follow up. The proportion of patients receiving a DMARD was understandably higher than in the initial analysis, but the variation between district hospital type and university and county hospital types remained, independent of potential confounding factors (table 1). The linear trend for the DAS28 indicates that a higher score was more likely to elicit a DMARD prescription. When methotrexate was included at follow up, patients over 65 years were significantly less likely to receive a DMARD than patients in the 46–55 year age group, regardless of the DAS28 (table 1). No other patient characteristics were associated with DMARD prescription.

Table 1 Influence of patient and disease characteristics on DMARD prescription at the initial consultation together with the unadjusted and adjusted odd ratios.

| Characteristics | No (%) with DMARD | No (%) without DMARD | Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | Sig. (p) | OR (95% CI) | Sig. (p) | |||

| Type of hospital | ||||||

| University | 1038 (53.0) | 168 (45.5) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| County | 512 (26.1) | 82 (22.2) | 1.22 (0.94 to 1.60) | 0.141 | 1.05 (0.78 to 1.41) | 0.751 |

| District | 408 (20.8) | 119 (32.2) | 0.64 (0.50 to 0.82) | 0.000 | 0.53 (0.40 to 0.69) | 0.000 |

| DAS28 at inclusion Linear trend | 1958 (100.0) | 369 (100.0) | 1.28 (1.18 to 1.40) | 0.000 | 1.33 (1.21 to 1.46) | 0.000 |

| RF | ||||||

| Negative | 671 (34.3) | 130 (35.2) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Positive | 1287 (65.7) | 239 (64.8) | 1.06 (0.85 to 1.32) | 0.618 | 0.94 (0.74 to 1.21) | 0.641 |

| Disease duration (months) | ||||||

| 0–3 | 478 (24.4) | 90 (24.4) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 4–6 | 642 (32.8) | 120 (32.5) | 0.96 (0.73 to 1.27) | 0.767 | 1.08 (0.79 to 1.48) | 0.618 |

| 7–9 | 495 (25.3) | 91 (24.7) | 0.98 (0.73 to 1.32) | 0.909 | 1.14 (0.81 to 1.58) | 0.456 |

| 10–12 | 343 (17.6) | 68 (18.4) | 0.94 (0.68 to 1.30) | 0.723 | 1.06 (0.74 to 1.52) | 0.767 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 603 (30.8) | 120 (32.5) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Female | 1355 (69.2) | 249 (67.5) | 1.06 (0.85 to 1.32) | 0.629 | 0.98 (0.76 to 1.26) | 0.885 |

| Age group | ||||||

| 16–25 | 64 (3.3) | 15 (4.1) | 0.76 (0.42 to 1.35) | 0.345 | 0.70 (0.37 to 1.32) | 0.273 |

| 26–35 | 141 (7.2) | 29 (7.9) | 0.82 (0.53 to 1.27) | 0.378 | 0.76 (0.47 to 1.25) | 0.281 |

| 36–45 | 208 (10.6) | 29 (7.9) | 1.12 (0.73 to 1.71) | 0.606 | 1.13 (0.70 to 1.82) | 0.616 |

| 46–55 | 425 (21.7) | 67 (18.2) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 56–65 | 466 (23.8) | 76 (20.6) | 1.08 (0.78 to 1.51) | 0.636 | 0.88 (0.61 to 1.26) | 0.472 |

| 66–75 | 429 (21.9) | 98 (26.6) | 0.78 (0.57 to 1.06) | 0.112 | 0.59 (0.42 to 0.84) | 0.004 |

| 76–85 | 220 (11.2) | 51 (13.8) | 0.71 (0.49 to 1.02) | 0.065 | 0.61 (0.43 to 0.93) | 0.021 |

| 86–95 | 5 (0.3) | 4 (1.1) | 0.11 (0.03 to 0.46) | 0.003 | 0.10 (0.02 to 0.45) | 0.003 |

| Year of inclusion | ||||||

| 1997 | 359 (18.3) | 119 (32.2) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 1998 | 422 (21.6) | 92 (24.9) | 1.49 (1.12 to 1.99) | 0.006 | 1.60 (1.17 to 2.20) | 0.003 |

| 1999 | 393 (20.1) | 49 (13.3) | 2.46 (1.77 to 3.43) | 0.000 | 2.76 (1.91 to 3.99) | 0.000 |

| 2000 | 394 (20.1) | 54 (14.6) | 2.41 (1.74 to 3.35) | 0.000 | 2.58 (1.80 to 3.70) | 0.000 |

| 2001 | 390 (19.9) | 55 (14.9) | 2.60 (1.86 to 3.63) | 0.000 | 2.36 (1.65 to 3.38) | 0.000 |

| Total | 1958 (100.0) | 369 (100.0) | ||||

Patients without a DMARD at the initial consultation but prescribed methotrexate at follow up are included in the analysis. Results are adjusted for age, sex, disease duration, RF, hospital type, year of inclusion, and DAS28.

Association of the DAS28 with the likelihood of a DMARD prescription appeared to be greater for patients in the district hospital stratum (OR = 1.65 (1.34 to 2.02), p<0.001) than in the university hospital (OR = 1.23 (1.07 to 1.41), p = 0.003) or county hospital strata (OR = 1.34 (1.01 to 1.63), p = 0.003). Whether association of the DAS28 with DMARD prescription differed between hospital types was tested using the interaction between the DAS28 and hospital type. Interaction of the DAS28 with district hospital type was found more likely to provide patients with a DMARD prescription than interaction between the DAS28 and university hospitals (adjusted OR = 1.37 (1.09 to 1.73), p = 0.007). There was no difference between university and county hospitals in this regard (adjusted OR = 1.01 (0.81 to 1.26), p = 0.938). The exclusion of patients with missing data did not significantly affect the results of the analysis.

Glucocorticosteroid prescription

GCs were prescribed to 37.9%, 43.3%, and 42.7% of patients in university, county, and district hospitals, respectively. Median dosages were 7.5 mg in university hospitals and 10 mg in both county and district hospitals with no change over the years. Most GCs were prescribed in combination with DMARDs. Patients in county hospitals were more likely than patients in university and district hospitals to be prescribed a GC (OR = 1.25 (1.03 to 1.51), p = 0.022). The prescription of GC monotherapy was not generally widespread (6.6% of patients in district hospitals); however, it was more likely in district hospitals (OR = 2.2 (1.42 to 3.41), p<0.001) than in university hospitals.

Discussion

Two main factors—the year of RA diagnosis and hospital type—were associated with the likelihood of being prescribed a DMARD. The increasing proportion of patients with early RA over time prescribed a DMARD at their first consultation appears to reflect changes in prescribing practice rather than any change in the characteristics of the patient population. Similar trends have been reported previously15; however, sulfasalazine use did not continue to rise in our population, and methotrexate alone accounted for the increase.

The patients in our study represent the majority of incident cases of early RA from the catchments of the participating hospitals, which are widely dispersed throughout Sweden. Not only are the age, sex, RF, and disease activity (DAS28) distributions of patients constant over the study period but also the associations of DMARD prescription with year were independent of all of these factors. Similarly, variation in prescribing practice between hospitals was independent of patient characteristics, so the lower rate of DMARD prescription in district hospitals is likely to reflect institutional differences in practice. The lack of association between RF status and DMARD prescription indicates again that institutional prescribing practice rather than disease characteristics influences which patients with early RA are prescribed DMARDs at their first consultation. Greater disease activity indicated by a higher DAS28 was more likely to elicit a DMARD prescription, but more so in district hospitals than in the other hospital types. Again, as we were able to adjust for other patient characteristics, these could not account for the variation in association of the DAS28 with DMARD prescription by hospital type. It is of note that the difference between district and university hospitals had almost disappeared by the end of the study period, indicating a more universal approach to DMARD prescription across hospital types.

In conclusion, the temporal trends in DMARD prescription indicate that rheumatologists in this study adopted an increasingly aggressive approach to the treatment of early RA from 1997 to 2001. The influence of hospital type on the prescription of DMARDs suggests that there is room for improvement in the management of early RA. The use of quality and surveillance arthritis registers may help to identify and define areas of unwarranted variation, which may be even more important when considering the increasing use of effective but expensive biological drugs.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the following centres and their Swedish RA Register representatives for allowing us to use their data: Yngve Adolfsson, Sunderby Hospital, Luleå; Ewa Berglin, Norrland's University Hospital, Umeå; Sven Tegmark, Gävle County Hospital; Jörgen Lysholm, Falu lasarett, Falun; Tommy Vingren, Karlstad's Central Hospital; Eva Baecklund, Akademiska Hospital, Uppsala; Birgitta Nordmark, Karolinska University Hospital, Solna; Ingiäld Hafström, Karolinska University Hospital, Huddinge; Göran Lindahl, Danderyd's Hospital, Stockholm; Göran Kvist, Centrallasarettet Borås; Lennart Bertilsson, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg; Monica Ahlmén, Sahlgreska University Hospital, Mölndal; Bengt Lindell, Kalmar County Hospital; Tore Saxne, University Hospital in Lund; Miriam Karlsson, Lasarettet Trelleborg; Annika Teleman, Spenshult, Oskarström; Catharina Keller, Helsingborg's Lasarett; Jan Theander, Kristianstad's Central Hospital; Christina Book, MAS University Hospital, Malmö.

Abbreviations

CI - confidence interval

DAS28 - 28 joint count Disease Activity Score

DMARD - disease modifying antirheumatic drug

GCs - glucocorticosteroids

HAQ - Health Assessment Questionnaire

OR - odds ratio

RA - rheumatoid arthritis

RF - rheumatoid factor

Footnotes

A full list of the contributing centres is given in the Acknowledgements.

Financial support was provided by the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare, and The Swedish Medical Research Council.

Competing interests: None.

References

- 1.Stenger A A, Van Leeuwen M A, Houtman P M, Bruyn G A, Speerstra F, Barendsen B C.et al Early effective suppression of inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis reduces radiographic progression. Br J Rheumatol 1998371157–1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Egsmose C, Lund B, Borg G, Petterson H, Berg E, Brodin U.et al Patients with rheumatoid arthritis benefit from early 2nd line therapy: 5 year follow‐up of a prospective double blind placebo controlled study. J Rheumatol 1995122208–2213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van der Heijde D M, Jacobs J W, Bijlsma J W, Heurkens A H, van Booma‐Frankfort, van der Veen M J.et al The effectiveness of early treatment with “second‐line” antirheumatic drugs: a randomised controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 1996124699–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mottonen T, Hannonen P, Korpela M, Nissila M, Kautiainen H, Ilonen J.et al Delay to institution of therapy and induction of remission using single‐drug or combination‐disease‐modifying antirheumatic drug therapy in early rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 200246894–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Criswell L A, Henke C J. What explains the variation among rheumatologists in their use of prednisolone and second line agents for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis? J Rheumatol 199522829–835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saraux A, Berthelot J M, Chales G, Le H C, Thorel J, Hoang S.et al Second‐line drugs used in recent‐onset rheumatoid arthritis in Brittany (France). Joint Bone Spine 20026937–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Albers J M C, Paimela L, Kurki P, Eberhardt K B, Emery P, van ‘t Hof M A.et al Treatment strategy, disease activity, and outcome in four cohorts of patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 200160453–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galindo‐Rodriguez G, Avina‐Zubieta J A, Fitzgerald A, LeClerq S A, Russell A S, Suarez‐Almazor M E. Variations and trends in the prescription of initial second line therapy for patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 199724633–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arnett F C, Edworthy S M, Bloch D A, McShane D J, Fries J F, Cooper N S.et al The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 198831315–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Felson D T, Anderson J J, Boers M, Bombardier C, Chernoff M, Fried B.et al The American College of Rheumatology preliminary core set of disease activity measures for rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials. The Committee on Outcome Measures in Rheumatoid Arthritis Clinical Trials. Arthritis Rheum 199336729–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ekdahl C, Eberhardt K, Andersson S I, Svensson B. Assessing disability in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Use of the Swedish version of the Stanford Health Assessment Questionnaire. Scand J Rheumatol 198817263–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prevoo M L, van Riel P L, van't Hof M A, van Rijswijk M H, van Leeuwen M A, Kuper H H.et al Validity and reliability of joint indices. A longitudinal study in patients with recent onset rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol 199332589–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prevoo M L, van't Hof M A, Kuper H H, van Leeuwen M A, van de Putte L B, van Riel P L. Modified disease activity scores that include twenty‐eight‐joint counts. Development and validation in a prospective longitudinal study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 19953844–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Norusis M J.SPSS user's guide. Chicago: SPSS Inc, 1998

- 15.Aletaha D, Eberl G, Nell V P, Machold K P, Smolen J S. Practical progress in realisation of early diagnosis and treatment of patients with suspected rheumatoid arthritis: results from two matched questionnaires within three years. Ann Rheum Dis 200261630–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]