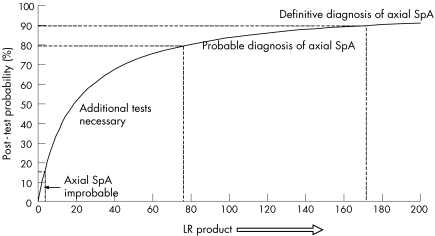

Making a diagnosis of ankylosing spondylitis in patients with chronic back pain can be difficult at an early stage—that is, before radiographic sacroiliitis is definitely present (also referred to as axial spondyloarthritis (SpA) at the preradiographic state). We recently proposed to diagnose patients at this early stage by probability estimations1 based on a pretest probability (ppre) of 5% in patients with chronic back pain.2 To facilitate the probability calculation in each patient, we subsequently3 proposed the use of likelihood ratios (LR).4 We suggested that the diagnosis could be considered definite if the post‐test probability (ppost) is ⩾90% (LR product ⩾171), probable if the post‐test probability is 80–90% (LR product 76–171) and unlikely if the post‐test probability is ⩽10–20% (LR product <2–4).1,3

Mainly because of the complicated mathematics, we previously3 concentrated on the use of positive likelihood ratios—that is, in case the parameter is present. However, when making a diagnosis in daily practice, a negative test result (absence of a certain parameter) sometimes helps to rule out a diagnosis. In axial SpA, a few parameters, if absent, clearly render the diagnosis less likely. These include negativity for human leucocyte antigen‐B27, a negative magnetic resonance image (showing no signs of inflammation), the absence of the inflammatory type of back pain, a normal C reactive protein level or erythrocyte sedimentation rate, no good response to non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs and, probably, a negative family history (discussed already by Rudwaleit et al1). On the other hand, other mostly clinical parameters should not be considered to be definitely absent if not present at disease onset, as these may occur later in the disease course and therefore are rather a function of disease duration. These include peripheral arthritis, enthesitis, dactylitis, acute anterior uveitis, psoriasis and inflammatory bowel disease. These parameters are helpful in increasing the disease probability if present, but should be ignored if absent at an early disease stage.

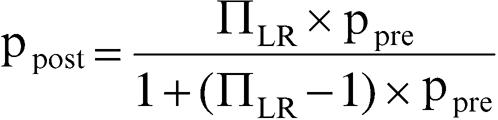

Table 1 shows the list of LR+ values for positive test results supplemented by LR− values for negative test results. The likelihood ratio product is calculated by multiplying the relevant LR+ and LR− values as derived from table 1, according to the presence or absence of particular features as appropriate. The final post‐test probability can be read from fig 1, which presents a probability curve showing the dependency of the post‐test probability on the LR product, again based on a pretest probability of 5%. The curve in fig 1 has been calculated using the formula

Table 1 Representative values of sensitivity and specificity for several tests relevant for axial spondyloarthritis as evaluated previously,1,3 along with the resulting LR+ and LR−*.

| Parameter | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | LR+ | LR− |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inflammatory type of back pain5,6 | 75 | 76 | 3.1 | 0.33 |

| Heel pain (enthesitis) | 37 | 89 | 3.4 | (0.71)† |

| Peripheral arthritis | 40 | 90 | 4.0 | (0.67)† |

| Dactylitis | 18 | 96 | 4.5 | (0.85)† |

| Iritis or anterior uveitis | 22 | 97 | 7.3 | (0.80)† |

| Psoriasis | 10 | 96 | 2.5 | (0.94)† |

| IBD | 4 | 99 | 4.0 | (0.97)† |

| Positive family history for axial SpA, reactive arthritis, psoriasis, IBD or anterior uveitis | 32 | 95 | 6.4 | 0.72 |

| Good response to NSAIDs | 77 | 85 | 5.1 | 0.27 |

| Raised acute‐phase reactants (CRP/ESR) | 50 | 80 | 2.5 | 0.63 |

| HLA‐B27‡ | 90 | 90 | 9.0 | 0.11 |

| Sacroiliitis shown by magnetic resonance imaging | 90 | 90 | 9.0 | 0.11 |

CRP, C‐reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; HLA, human leucocyte antigen; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; LR+, positive likelihood ratio; LR−, negative likelihood ratio; NSAID, non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs; SpA, spondyloarthritis.

*LR+ = sensitivity/(1 – specificity); LR− = (1 – sensitivity)/specificity.

†As enthesitis, dactylitis, uveitis, peripheral arthritis, psoriasis and IBD may not be present at disease onset but may develop later, it is recommended to ignore a negative test result of these tests in an early state of possible axial SpA. The LR− of parameters, which should be ignored, are shown in brackets.

‡The figures for sensitivity and specificity of HLA‐B27 refer to a European Caucasian population. In European Caucasian patients with psoriasis or IBD, a sensitivity of 50%, a specificity of 90%, an LR+ of 5.0 and an LR− of 0.56 for HLA‐B27 should be applied. In other ethnic populations, sensitivity and specificity of HLA‐B27 may be different, resulting in different LR+ and LR− (also discussed by Rudwaleit et al1).

Figure 1 Dependency of the post‐test probability of axial spondyloarthritis (SpA) on the resulting likelihood ratio (LR) product for an assumed pretest probability of 5% (according to Underwood and Dawes2). This probability curve is meant to be applied in patients with chronic back pain suspected to have axial SpA.

|

where ppost is the post‐test probability, ΠLR the product of likelihood ratios and ppre the pretest probability.

Thus, taking into account all positive and negative diagnostic test results as appropriate, the disease probability of axial SpA at the preradiographic stage in a patient with chronic back pain can now be easily assessed at the bedside with the help of table 1 and fig 1.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by a grant from the BMBF (Kompetenznetz Rheuma), FKZ 01GI9946.

References

- 1.Rudwaleit M, van der Heijde D, Khan M, Braun J, Sieper J. How to diagnose axial spondyloarthritis early? Ann Rheum Dis 200463535–543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Underwood M R, Dawes P. Inflammatory back pain in primary care. Br J Rheumatol 1995341074–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rudwaleit M, Khan M, Sieper J. The challenge of classification and diagnosis of early ankylosing spondylitis—do we need new criteria? Arthritis Rheum 2005521000–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grimes D A, Schulz K F. Refining clinical diagnosis with likelihood ratios. Lancet 20053651500–1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calin A, Porta J, Fries J F, Schurman D J. Clinical history as a screening test for ankylosing spondylitis. JAMA 19772372613–2614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rudwaleit M, Metter A, Listing J, Sieper J, Braun J. Inflammatory back pain in anyklosing spondylitis—a reassessment of the clinical history for application as classification and diagnostic criteria. Arthritis Rheum 200654569–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]