Abstract

Rheumatoid arthritis among elderly people is an increasingly important health concern. Despite several cross‐sectional studies, it has not been clearly established whether there are important clinical differences between elderly‐onset rheumatoid arthritis (EORA) and younger‐onset rheumatoid arthritis (YORA). The aim of this study was to compare disease activity and treatment in EORA and YORA, using the Consortium of Rheumatology Researchers of North America (CORRONA) registry, a database generated by rheumatologist investigators across the USA. From the CORRONA registry database of 9381 patients with rheumatoid arthritis, 2101 patients with disease onset after the age of 60 years (EORA) were matched, on the basis of disease duration, with 2101 patients with disease onset between the ages of 40 and 60 years (YORA). The primary outcome measures were the proportion of patients on methotrexate, multiple disease‐modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARD) and biological agents (etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab and kineret) in each group. Disease activity and severity differed slightly between the EORA and YORA groups: Disability Index of the Health Assessment Questionnaire: 0.30 v 0.35; tender joint count: 3.7 v 4.7; swollen joint count: 5.3 v 5.2; Disease Activity Score 28: 3.8 v 3.6; patient global assessment: 29.1 v 30.9; physician global assessment: 24.9 v 26.3; patient pain assessment: 31.4 v 34.9. Regarding treatment, the use of methotrexate use was slightly more common among patients with EORA (63.9%) than among those with YORA (59.6%), although the mean methotrexate dose among the YORA group was higher than that in the EORA group. The percentage of patients with EORA who were on multiple DMARD treatment (30.9%) or on biological agents (25%) was considerably lower than that of patients with YORA (40.5% and 33.1%, respectively; p<0.0001). Toxicity related to treatment was very minimal in both groups, whereas toxicities related to methotrexate were more common in the YORA group. Patients with EORA receive biological treatment and combination DMARD treatment less frequently than those with YORA, despite identical disease duration and comparable disease severity and activity.

Rheumatoid arthritis, the most common form of inflammatory arthritis, is a major cause of morbidity and disability. Disability is of particular concern among elderly people aged ⩾60 years, as it is a chronic disease and because its peak incidence is in the fourth and fifth decades of life.1

Rheumatoid arthritis in older people can represent disease initially arising after the age of 60 or it can be a continuation of disease that had started at an earlier age. The available data from the literature are inconsistent on whether elderly‐onset rheumatoid arthritis (EORA) has important clinical distinctions as compared with younger‐onset rheumatoid arthritis (YORA). The presence of comorbid conditions and uncertainty about the safety of treatment modalities in this population group can render therapeutic decision‐making potentially difficult for elderly patients with rheumatoid arthritis.2,3

Our study aimed to compare disease activity and the use of different treatment modalities in patients with EORA and YORA, by using data from the Consortium of Rheumatology Researchers of North America (CORRONA) database.

Methods

The CORRONA database includes patients with different rheumatological conditions seen by 192 rheumatologist investigators across the USA. From the 9381 patients with rheumatoid arthritis enrolled in the database as of September 2005, 2101 patients who had onset of disease after the age of 60 years (EORA) were matched, on the basis of their disease duration, with an equal number of patients with rheumatoid arthritis who had onset of disease between the ages of 40 and 60 years (YORA). Further analysis was carried out comparing the 1299 patients with EORA who had disease onset between the ages of 60 and 70 with those with YORA who had disease onset between the ages of 40 and 50; the 797 patients with EORA who had onset of disease after the age of 70 were compared with those with YORA who had onset of disease between the ages of 50 and 60.

The two groups were compared in various disease activity measures, including Disease Activity Score (DAS)28, Disability Index of the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ DI), tender joint count (TJC), swollen joint count (SJC), physician global assessment (PhGA), patient global assessment (PGA) and patient pain assessment (PPA; table 1). We queried the use of specific disease‐modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) and biological agents (etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab and kineret). Factors predicting the use of methotrexate, multiple DMARD and biological agents were analysed, and methotrexate dose distribution was estimated for each group. In addition, other elements that may have an effect on the choice of therapeutic agents, such as comorbidities and weight of the patient, were investigated.

Table 1 Characteristics of patients by various disease‐activity measures.

| Age at onset of RA | p Value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ⩾60 years | 40–60 years | ||||||

| Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | n | ||

| Age (years) | 73.7 | 7.3 | 2101 | 55.2 | 7.2 | 2101 | 0.000 |

| Weight (lbs) | 164.6 | 38.0 | 2031 | 182.3 | 44.6 | 2051 | 0.000 |

| Duration of RA (years) | 5.3 | 5.1 | 2101 | 5.3 | 5.1 | 2101 | 1.000 |

| Disability Index | 0.30 | 0.4 | 2041 | 0.35 | 0.4 | 2053 | 0.001 |

| DAS28 | 3.8 | 1.5 | 766 | 3.6 | 1.6 | 769 | 0.112 |

| TJS | 3.7 | 5.5 | 2065 | 4.7 | 6.1 | 2064 | 0.000 |

| SJS | 5.3 | 6.2 | 2064 | 5.2 | 6.1 | 2066 | 0.502 |

| PhGA | 24.9 | 20.9 | 2089 | 26.3 | 21.9 | 2084 | 0.032 |

| Patient VAS general | 29.1 | 25.7 | 1943 | 30.9 | 26.2 | 1986 | 0.030 |

| Patient VAS for pain | 31.4 | 26.0 | 1983 | 34.0 | 26.7 | 2022 | 0.001 |

DAS, Disease Activity Score; PhGA, physician global assessment; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; SJS, Swollen Joint Score; TJS, Tender Joint Score; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale.

Statistical methods

Analyses were carried out using SAS V.9.1. All analyses accounted for subject clustering by duration of disease. Odds ratios (ORs) were estimated using conditional logistic regression analyses. Estimates of differences in methotrexate dose were made using a random effects model with duration of disease as the random effect (thus clustering on duration of disease). ORs for risks of toxicities were estimated using random effects logistic regression with duration and patient (nested in the duration group) as random effects.

Results

Comorbidities were more common among the EORA group than among the YORA group: coronary artery disease: 8.9% v 3.7%; myocardial infarction: 5.9% v 3.0%; hypertension: 41.1% v 27.4%; stroke: 3.8% v 1.4%, respectively. Interestingly, patients with YORA were heavier than those with EORA (mean: 182.3 v 164.6 lbs, respectively). Scores for several measures, such as the HAQ DI, TJC, PGA and PPA, were higher among patients with YORA, whereas the DAS28 and SJC were comparable (table 2).

Table 2 Characteristics of patients by comorbidities.

| Age at onset of RA | p Value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ⩾60 years | 40–60 years | ||||||

| % | Freq | n | % | Freq | n | ||

| Sex (female) | 69.3 | 1440 | 2077 | 71.9 | 1506 | 2094 | 0.072 |

| Use of methotrexate | 63.9 | 1342 | 2101 | 59.6 | 1253 | 2101 | 0.005 |

| Use of biological agent | 25.0 | 525 | 2101 | 33.1 | 696 | 2101 | 0.000 |

| Use of >1 DMARD | 30.9 | 649 | 2101 | 40.5 | 851 | 2101 | 0.000 |

| Use of prednisone | 41.0 | 837 | 2039 | 37.64 | 778 | 2067 | 0.025 |

| Hx of peptic ulcer disease | 6.4 | 135 | 2101 | 5.6 | 118 | 2101 | 0.299 |

| Hx of CAD | 8.9 | 187 | 2101 | 3.7 | 77 | 2101 | 0.000 |

| Hx of GERD | 16.8 | 353 | 2101 | 16.7 | 352 | 2101 | 1.000 |

| Hx of MI | 5.9 | 125 | 2101 | 3.0 | 63 | 2101 | 0.000 |

| Hx of hypertension | 41.4 | 870 | 2101 | 27.4 | 575 | 2101 | 0.000 |

| Hx of stroke | 3.8 | 79 | 2101 | 1.4 | 30 | 2101 | 0.000 |

| Hx of CVD* | 14.4 | 303 | 2101 | 6.6 | 138 | 2101 | 0.000 |

CAD, coronary artery disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DMARD, disease‐modifying antirheumatic drug; Freq, frequency; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; Hx, history; MI, myocardial infarction; RA, rheumatoid arthritis.

*CAD, MI, stroke combined.

The use of methotrexate was more common in patients with EORA (63.9% v 59.6%; p<0.01). However, the percentage of patients with EORA who were on multiple DMARD treatment (30.9%) or on biological agents (25%) was markedly lower than those with YORA (40.5% and 33.1%, respectively; p<0.0001). The use of prednisone was slightly higher among patients with EORA (41%) than among those with YORA (37.64%; p<0.05; table 2).

Predictors of the use of methotrexate, multiple DMARD and biological treatments were estimated using conditional logistic regression analysis. EORA, low HAQ DI, TJC, SJC and PGA correlated with use of methotrexate, whereas YORA, high HAQ DI, high DAS28, TJC, SJC, PhGA score, PGA score and use of prednisone correlated with biological usage. YORA, high HAQ DI, DAS28, TJC, SJC, PGA and use of prednisone correlated with use of multiple DMARDs. Among the comorbidities investigated in this study population, only history of hypertension was a negative predictor of the use of biological agents and multiple DMARDs. The presence of other comorbidities did not seem to have an influence on the choice of therapeutic agents.

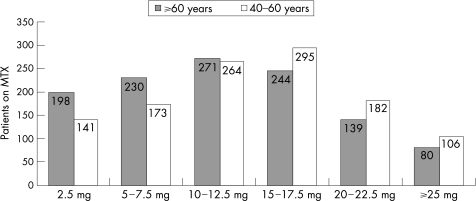

Although methotrexate was more commonly used by patients with EORA, the weekly methotrexate dose was considerably lower among them (mean = 11.96 mg, median = 11.25 mg) than in those with YORA (mean = 13.53 mg, median = 16.25 mg). Methotrexate dose also correlated with weight, TJC and use of prednisone. The distribution of methotrexate dose among patients with YORA and EORA is shown in fig 1.

Figure 1 Distribution of methotrexate (MTX) dose.

Although toxicities related to the use of biological treatments, including rash (n = 11), lung disease (n = 10), haematological disorder (n = 6), nausea (n = 3), diarrhoea (n = 2), congestive heart failure (n = 1) and drug‐induced lupus (n = 1), were similar between groups (p = 0.803), toxicities related to methotrexate were seen more commonly in the YORA group (p = 0.01). The most commonly observed MTX‐associated toxicities included liver disorder (n = 34), lung disease (n = 17), nausea (n = 15), haematological disorder (n = 15), alopecia (n = 7), dyspepsia (n = 7), rash (n = 4), diarrhoea (n = 4) and peptic ulcer (n = 1).

Discussion

Our study shows that despite comparable disease severity and activity and an identical disease duration, there were differences in treatment between patients with EORA and those with YORA. Specifically, patients with EORA were less likely to receive treatment with biological agents and with combination DMARD. As these treatments are sometimes considered to be “aggressive”, it may be inferred that patients with EORA are less likely to receive intensive treatment than those with YORA, despite comparable disease activity. Provider factors, such as concern for toxicity or less experience with intensive treatments in patients with EORA, may be the cause for such disparity. Because of the widespread consideration that drugs can have differential toxicity among older people, providers, not uncommonly, adopt a “start low, go slow” general approach to pharmacological treatments for them. Alternatively, patient‐related factors, such as fear of trying treatments with potentially marked side effects, may also be associated, as may pharmacoeconomical or psychosocial issues. Nevertheless, as the rheumatological community increasingly accepts the necessity of intensive treatment of rheumatoid arthritis to achieve minimal disease activity and optimise the outcomes, it will be important to extend this to all segments of the population, including older patients.

Controlling for disease duration is critical in comparisons of treatments, as it has been noted that longer disease duration is associated with reduced response to treatment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Patients with longer disease duration are also at greater risk for disability and treatment‐related complications. To exclude the effect of long disease duration, patients with EORA and YORA were matched according to their disease duration in this analysis.

Current management strategies in the elderly population may be based more on assumptions than on evidence. Some reports suggest that there is a tendency towards reduced efficacy and more toxicity with DMARD in older patients than in younger patients. However, the elderly population identified in those studies may have had longer disease duration.

Relatively limited data are available on treatment of patients with EORA. Observational studies on the use of DMARDs on elderly patients with rheumatoid arthritis showed no significant difference between the older and the younger patients with regard to efficacy, side effects and discontinuation of DMARDs.4,5,6 On the other hand, a tendency towards reduced efficacy and toxicity of DMARDs has been reported in older patients in some reports.7,8 Some authors have suggested a greater prevalence of methotrexate intolerance among elderly people.9

Tumour necrosis factor α blockers have been used in elderly people, but data regarding the efficacy and toxicity of these agents in this population are limited. In a reanalysis of a clinical trial, etanercept was found to have comparable safety and efficacy among elderly patients with rheumatoid arthritis.10

Despite the well‐documented side effects of long‐term steroid treatment, the use of oral prednisone has been reported to be quite common in the elderly population. Some authors suggest that palliative care with oral prednisone treatment should be started earlier in the elderly patients with rheumatoid arthritis because of the higher risk of permanent loss of independence in this group.11 However, even with low‐dose prednisone, the risk of side effects may outweigh the clinical benefit with long‐term use.12,13,14

In this study, patients with EORA received biological treatment and combination DMARD treatment less frequently than those with YORA. Although the percentage of patients who were on methotrexate was higher in the EORA group, the mean dose of methotrexate in the EORA group was considerably lower than that in the YORA group and the use of prednisone was greater in the EORA group than in the YORA group. Importantly, the toxicities due to methotrexate and biological agents were minimal in both groups. The rate of toxicity was comparable between groups of patients who were on biological agents, whereas toxicities related to methotrexate were higher in the YORA group. This may have been because the patients with YORA were on higher doses of methotrexate. The difference in methotrexate dosage and the frequency of biological use in the elderly population may also reflect factors such as reduced clinical activity, lower weight or an increased rate of comorbidities. The slightly lower doses of methotrexate and less frequent use of biological agents may simply imply good clinical practice and adjustment by the clinician to the patient's status.

As various intensive treatment paradigms with traditional DMARDs and biological agents such as tumour necrosis factor inhibitors become used more widely among elderly patients with rheumatoid arthritis, longer‐term data regarding their safety and efficacy specifically in this population will emerge. Greater efforts to include elderly patients in clinical research of diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis will be crucial. Data from these sources will help clinicians optimise the care of older patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

Abbreviations

CORRONA - Consortium of Rheumatology Researchers of North America

DAS - Disease Activity Score

DMARD - disease‐modifying antirheumatic drug

EORA - elderly‐onset rheumatoid arthritis

HAQ DI - Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index

PGA - patient global assessment

PhGA - physician global assessment

PPA - patient pain assessment

SJC - swollen joint count

TJC - tender joint count

YORA - younger‐onset rheumatoid arthritis

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Kerr L D. Inflammatory arthropathy: a review of rheumatoid arthritis in older patients. Geriatrics 20045932–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Schaardenburg D, Breedweld F C. Elderly‐onset rheumatoid arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 199423367–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kavanaugh A F. Rheumatoid arthritis in the elderly: is it a different disease? Am J Med 199710340S–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pincus T, Marcum S B, Callahan L F, Adams R F, Barber J, Barth W F.et al Long term drug therapy for rheumatoid arthritis in seven rheumatology private practices. Second line drugs and prednisone. J Rheumatol 1992191885–1894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Capell H A, Porter D R, Madhok R, Hunter J A. Second line (disease modifying) treatment in rheumatoid arthritis: which drug for which patient? Ann Rheum Dis 199352423–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dahl S L, Samuelson C O, Williams J, Ward J R, Karg M. Second line antirheumatic drugs in the elderly with rheumatoid arthritis: a post hoc analysis of three controlled trials. Pharmacotherapy 19901079–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deal C L, Meenan R D, Goldenberg D L, Anderson J J, Sack B, Pastan R S.et al The clinical features of elderly‐onset rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 198528987–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferraccioli G F, Cavelieri F, Mercadanti M, Conti G, Viviano P, Ambanelli U.et al Clinical features, scintiscan characteristics and X‐ray progression of late onset rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 19842157–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drosos A. Methotrexate intolerance in elderly patients with rheumatoid arthritis: what are the alternatives? Drugs Aging 200320723–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glennas A, Kvien T K, Andrup O, Karstensen B, Munthe G. Recent onset arthritis in the elderly: a five year longitudinal observational study. J Rheumatol 200027101–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kerr L D. Inflammatory arthritis in the elderly. Mount Sinai J Med 20037023–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Healey L A, Sheets P K. The relation of polymyalgia rheumatica to rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 198815750–752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lockie L M, Gomez E, Smith D M. Low dose adrenocorticosteroids in the management of elderly patients with rheumatoid arthrtitis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 198312373–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Schaardenburg D, Valkema R, Dijkmans B A, Papapoulos S, Zwinderman A H, Han K H.et al Prednisone for elderly‐onset rheumatoid arthritis: efficacy and bone mass at one year. Arthritis Rheum 199336S269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]