Abstract

Background

Intestinal inflammation is a common feature of spondyloarthropathy (SpA) and Crohn's disease. Inflammation is manifested clinically in Crohn's disease and subclinically in SpA. However, a fraction of patients with SpA develops overt Crohn's disease.

Aims

To investigate whether subclinical gut lesions in patients with SpA are associated with transcriptome changes comparable to those seen in Crohn's disease and to examine global gene expression in non‐inflamed colon biopsy specimens and screen patients for differentially expressed genes.

Methods

Macroarray analysis was used as an initial genomewide screen for selecting a comprehensive set of genes relevant to Crohn's disease and SpA. This led to the identification of 2625 expressed sequence tags that are differentially expressed in the colon of patients with Crohn's disease or SpA. These clones, with appropriate controls (6779 in total), were used to construct a glass‐based microarray, which was then used to analyse colon biopsy specimens from 15 patients with SpA, 11 patients with Crohn's disease and 10 controls.

Results

95 genes were identified as differentially expressed in patients with SpA having a history of subclinical chronic gut inflammation and also in patients with Crohn's disease. Principal component analysis of this filtered set of genes successfully distinguished colon biopsy specimens from the three groups studied. Patients with SpA having subclinical chronic gut inflammation cluster together and are more related to those with Crohn's disease.

Conclusion

The transcriptome in the intestine of patients with SpA differs from that of controls. Moreover, these gene changes are comparable to those seen in patients with Crohn's disease, confirming initial clinical observations. On the basis of these findings, new (genetic) markers for detection of early Crohn's disease in patients with SpA can be considered.

The clinical association between spondyloarthropathy (SpA) and Crohn's disease is shown by the concurrence of similar arthropathy and intestinal inflammation in patients with either disease, indicating a shared aetiology and pathogenesis. Depending on the imaging technique used, up to one third of patients with Crohn's disease have peripheral or sacroiliac joint abnormalities similar to those seen in various subgroups with SpA.1,2 In addition, 60% of patients with SpA who have no evidence of Crohn's disease exhibit endoscopic or histological signs of subclinical gut inflammation.3 In general, two types of inflammation are observed: acute inflammation as seen in infectious colitis and chronic inflammation resembling that seen in Crohn's disease.3 A striking parallel exists between the activity of inflammation at the joints and at the intestine. Moreover, long‐term evolution to Crohn's disease was observed in 13% of patients with SpA with initial chronic gut inflammation, supporting the concept of preclinical Crohn's disease in those patients.4 Since these clinical observations, several studies provided additional evidence for a joint–gut axis on the molecular and the genetic levels. The early immunological changes observed are up regulation of αEβ7 integrin on T cell lines from patients with SpA and an increase in lymphoid follicles and lamina propria mononuclear cells in intestinal biopsy specimens.5,6,7 Increased expression of αΕβ7 and the E‐cadherin–catenin complex was found in the gut mucosa from patients with Crohn's disease and in those with SpA.5,8 A specific subset of CD163 macrophages is augmented in both groups of patients, supporting the hypothesis of a recirculation of similar clones in the intestinal mucosa and synovium.9

Both Crohn's disease and SpA are complex genetic traits, because many genes are probably associated in the pathogenesis, and environmental factors have a substantial influence on the outcome of the disease. Evidence exists for a common genetic risk factor in the development of subclinical intestinal inflammation in first‐degree relatives of patients with ankylosing spondylitis, which is the prototype of SpA.10 Furthermore, we found that CARD15, which was the first gene identified for susceptibility to Crohn's disease, is associated with chronic subclinical inflammation in patients with SpA.11 In this regard, patients with SpA can serve as a unique model for detection of early genetic markers for Crohn's disease.

To determine whether the association between the two disorders occurs at the clinical and also at the transcriptome level, we compared global gene expression in non‐inflamed colon biopsy specimens from patients with SpA and those with Crohn's disease. We propose that it is possible to identify a set of genes that distinguish patients with Crohn's disease and those with SpA having a history of chronic gut inflammation from patients with SpA without chronic gut inflammation and from controls.

Participants and methods

Patients, tissue collection and histological classification

Colon biopsy specimens from patients with Crohn's disease and with SpA and from healthy controls were obtained during colonoscopy. All biopsy specimens were taken from the non‐inflamed sigmoid at 30 cm, immediately placed in RNA later (Ambion, Cambridgeshire, UK) and frozen at −80°C until the sample was processed. Three specimens were obtained from each of 34 patients diagnosed with Crohn's disease according to clinical, endoscopic and histological criteria and from 20 patients diagnosed with SpA according to the criteria of the European Spondylarthropathy Study Group.12 Sixteen patients without clinical manifestations of Crohn's disease or SpA, who were undergoing colonoscopy for colon cancer screening, were included as controls .

Histological classification of the ileum and colon in patients with SpA was carried out as in our previous studies.3,4,13,14,15 We distinguished three classes: patients with normal histology, those with acute inflammatory lesions, and those with chronic inflammatory lesions.16 In acute lesions, normal architecture was well preserved. Infiltration by neutrophils and eosinophils was seen, without a considerable increase in lymphocytes. Small superficial ulcers covered with fibrin and neutrophils overlying hyperplastic lymphoid follicles were occasionally observed. The lamina propria was oedematous and haemorrhagic, containing mainly polymorphonuclear cells. The pattern of inflammation was similar to that seen in acute self‐limiting bacterial enterocolitis. The principal features of chronic lesions were crypt distortion, atrophy of the villous surface of the mucosa, villous blunting and fusion, increased mixed cellularity, and the presence of basal lymphoid aggregates in the lamina propria. Although several biopsy specimens were obtained from each patient, a diagnosis of chronic inflammation was made even if only one specimen showed chronic lesions, regardless of acute or active inflammation in the other specimens.

Patients with SpA who had chronic inflammation in the colon or ileum in previous examinations were termed patients with SpA with chronic gut inflammation.

RNA extraction

Total RNA was extracted from biopsy specimens using the Qiagen Rneasy Mini Kit (Westburg BV, Leusden, The Netherlands) with on‐column DNAse treatment (Qiagen). Needle homogenisation was carried out. Quality and concentration of RNA were checked on the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany).

Macroarray hybridisation and analysis

Colony filters containing 74 828 expressed sequence tag (EST) clones (Human UniGene collection 2, RZPD, Germany) were used as initial screen. Radioactively labelled probes were produced by incorporation of α.33P‐labelled deoxycytidine triphosphate during reverse transcription of 50 μg total RNA (MMLV, Promega, Leiden, The Netherlands), using oligodT as primer. 33P‐cDNA probes were purified on G‐50 spin columns (Amersham Biosciences, Roosendaal, The Netherlands). Hybridisation was carried out at 106 cpm/ml at 65°C for 20 h. Images were acquired after 6, 18 and 24 h of exposure, by using a Phosphorimager system (Amersham Biosciences). Spot definition and intensity measurement were carried out with Visualgrid (GPC Biotech AG, Munich, Germany). The raw expression data were processed with an in‐house algorithm based on MS Access. Spot intensities were corrected for the local background, followed by a quality control of spots to exclude those influenced by intense signals of adjacent spots. The detection limit for expression values above background was calculated on the basis of the variation in the local background intensity. Constitutive genes (those that show the lowest coefficient of variation over all arrays) were used for normalisation. Subsequently, quantitative measures of each clone (gene) were calculated by log2 transformation of the ratio of the mean spot intensity in samples from patients with Crohn's disease or with SpA to the mean spot intensity in samples from controls.

Microarray hybridisation, scanning and analysis

Construction of a focus microarray chip, probe labelling, hybridisation, washing and scanning were carried out at the MicroArray Facility of the Flanders Interuniversity Institute for Biotechnology (MAF, Leuven, Belgium). Clones selected from the macroarray screen were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from RZPD clones by using universal M13 primers. PCR fragments were purified on MultiScreen PCR plates (Millipore, Brussels, Belgium) and resuspended in 50% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at an average concentration of 100 ng/μl. The PCR products were arrayed in duplicate on Type VII silane‐coated slides with a Molecular Dynamics Generation III printer (Amersham Biosciences, Buckinghamshire, UK). Total RNA (5 μg) was amplified using a modified protocol of in vitro transcription, as described previously.17 In all, 5 μg of the amplified RNA was labelled with Cy3 or Cy5 as described at http:\\www.microarrays.be\service.htm. Arrays were scanned at 532 and 635 nm with a Generation III scanner (Amersham BioSciences). Images were analysed using ArrayVision (Imaging Research, Ontario, Canada). Each hybridisation was repeated in a dye swap experiment. Spot intensities were measured, corrected for local background, and those that exceeded the background by more than two standard deviation (SD) values were included. For each gene, ratios of red (Cy5) to green (Cy3) intensities (I) were calculated and normalised with a Lowess Fit of the log2 ratios (log2(ICy5/ICy3)) over the log2 total intensity (log2(ICy5×ICy3)).

For comparing the microarray datasets, a mixture of RNA from five patients with Crohn's disease, five patients with SpA and five controls was used as reference RNA. This reference sample provides a positive hybridisation signal at each probe element on the microarray, which is essential when calculating and comparing fluorescence ratios. The data were imported into GeneMaths XT (Applied Maths, St‐Martens‐Latem, Belgium). Weighted mean ratios and their corresponding errors (pixel SD) were calculated from the dye swap. Data were normalised over all arrays and missing values were imputed using the k‐nearest‐neighbour algorithm (20 neighbours). GeneMaths XT was used for all subsequent supervised and unsupervised analyses.

Statistics

All p values chosen for cut‐off are subjective.

Results

Design of the custom microarray

To provide a practical and cost‐effective tool for conducting a large number of hybridisations, a self‐designed focus microarray chip was constructed specifically for studying colonic gene expression in patients with SpA and with Crohn's disease. To accomplish this, a genomewide survey of gene expression in colon biopsy specimens from four patients with Crohn's disease, four patients with SpA and six controls was conducted using high‐density nylon arrays containing 74 828 cDNA sequences (table 1, macroarrays).

Table 1 Study population.

| Diagnosis | Sample | Sex | Age (years) | SpA | Gut histology | Clinical CD | CD location | Drug | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Macroarrays | Control | 1 | F | 59 | No | Normal | No | – | |

| 2 | F | 45 | No | Normal | No | – | |||

| 3 | F | 55 | No | Normal | No | – | |||

| 4 | M | 30 | No | Normal | No | – | |||

| 5 | F | 58 | No | Normal | No | – | |||

| 6 | M | 40 | No | Normal | No | – | |||

| CD | 7 | M | 21 | No | Chronic | Yes | IC | – | |

| 8 | F | 48 | No | Chronic | Yes | IC | 5‐ASA | ||

| 9 | F | 41 | Yes | Chronic | Yes | C | – | ||

| 10 | F | 23 | No | Chronic | Yes | C | AZA | ||

| SpA | 11 | M | 47 | Yes | Normal | No | – | ||

| 12 | F | 85 | Yes | Normal | No | – | |||

| 13 | F | 60 | Yes | Normal | No | – | |||

| 14 | F | 43 | Yes | Chronic | Yes | – | |||

| Microarrays | Control | 1 | M | 54 | No | Normal | No | – | |

| 2 | F | 64 | No | Normal | No | – | |||

| 3 | F | 72 | No | Normal | No | – | |||

| 4 | M | 51 | No | Normal | No | – | |||

| 5 | F | 21 | No | Normal | No | – | |||

| 6 | F | 68 | No | Normal | No | – | |||

| 7 | F | 32 | No | Normal | No | – | |||

| 8 | F | 73 | No | Normal | No | – | |||

| 9 | F | 66 | No | Normal | No | – | |||

| 10 | M | 76 | No | Normal | No | – | |||

| CD | 11 | F | 23 | No | Chronic | Yes | IC | 5‐ASA | |

| 12 | F | 39 | Yes | Chronic | Yes | C | – | ||

| 13 | M | 51 | No | Chronic | Yes | C | – | ||

| 14 | M | 43 | No | Chronic | Yes | I | – | ||

| 15 | M | 36 | No | Chronic | Yes | IC | – | ||

| 16 | F | 27 | No | Chronic | Yes | IC | – | ||

| 17 | F | 46 | Yes | Chronic | Yes | IC | AZA | ||

| 18 | F | 23 | No | Chronic | Yes | IC | – | ||

| 19 | M | 19 | No | Chronic | Yes | IC | – | ||

| 20 | F | 26 | No | Chronic | Yes | IC | – | ||

| 21 | F | 36 | No | Chronic | Yes | IC | – | ||

| SpA | 22 | M | 40 | AS periph | Acute | No | – | ||

| 23 | M | 29 | AS periph | Normal | No | NSAID | |||

| 24 | M | 42 | AS periph | Acute | No | – | |||

| 25 | M | 31 | AS periph | Acute | No | NSAID | |||

| 26 | M | 76 | USpA | Normal | No | Steroids | |||

| 27 | F | 28 | AS ax | Normal | No | NSAID | |||

| 28 | M | 58 | AS periph | Normal | No | – | |||

| 29 | M | 38 | AS ax | Normal | No | Sulfa | |||

| 30 | F | 49 | AS periph | Chronic | No | Sulfa | |||

| 31 | M | 49 | AS periph | Chronic | No | – | |||

| 32 | M | 45 | AS periph | Chronic | No | Sulfa | |||

| 33 | M | 29 | USpA | Acute | No | Sulfa+NSAID | |||

| 34 | M | 48 | AS periph | Normal | No | NSAID | |||

| 35 | F | 44 | AS periph | Chronic | Yes | IC | Sulfa+AZA | ||

| 36 | M | 36 | AS ax | Normal | No | Sulfa+NSAID |

5‐ASA, 5‐aminosalicylates; AS ax, ankylosing spondylitis with only axial involvement; AS periph, ankylosing spondylitis with peripheral involvement; AZA, azathioprine; C, colonic involvement only; CD, Crohn's disease; F, female; I, ileal involvement only; IC, ileocolonic; M, male; NSAID, non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drug; SpA, spondyloarthropathy; Sulfa, sulfasalazine; USpA, undifferentiated SpA.

Histology of patients with SpA is a historical classification.

Spots that showed aberrant morphology, encompassed variation in replicates or were impaired because of overshining (characteristic of radioactive signals) were filtered out and considered to be clones lost through experimental error. To select for clones that were differentially expressed in patients with Crohn's disease or with SpA, we arbitrarily selected for those that have a log2‐transformed mean ratio of <−0.6 or >+0.6 (1.5‐fold down regulated or up regulated). Genes that may be differentially expressed between groups (control v patients with Crohn's disease or control v those with SpA) were identified using a simple algorithm based on the t test (p<0.05) and F values (p<0.05) as selection criteria, provided that at least three consistent intensity values were present in each group. F values were chosen for selection because we believed that differences in variances within groups might be important. A total of 2652 clones were identified as “potentially differentially expressed”. These genes together with 4127 ESTs lost through experimental error—which may include, besides control ESTs, additional differentially expressed genes—were used to produce a glass‐based microarray platform. This allowed us to screen more patients in a more accurate and sensitive manner.

Clustering of unfiltered data

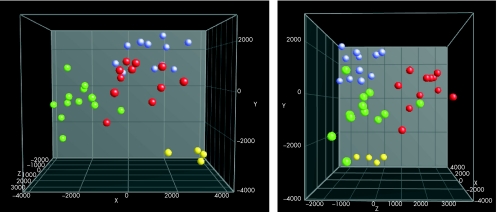

We hybridised independent cohorts of patients: 15 with SpA, 11 with Crohn's disease and 10 controls to the focus microarray (table 1, microarrays). Unsupervised clustering (without prior knowledge of groups) using all genes showed no clustering with respect to disease or phenotype (eg, type of intestinal inflammation). The inability to find discriminatory genes by using unfiltered data is not surprising, as we are analysing the steady‐state transcriptome in non‐inflamed tissue samples of complex inflammatory diseases. Subtle differences that exist in only a few genes are lost in the vast number of random variations. The problem of detecting differentially expressed genes can be overcome by carrying out supervised clustering. To this end, we divided the patients into four main groups: Crohn's disease, SpA and chronic gut inflammation, SpA without chronic gut inflammation, and controls. Discriminant analysis can reduce n‐dimensional data into a more visual two‐dimensional or three‐dimensional plot, with prior knowledge of groups (fig 1). With this approach, these groups became clearly separated, indicating that our full dataset contains genes that can differentiate between these disease states.

Figure 1 Discriminant analysis of all patients by using unfiltered data, shown in two directions. Four groups are clearly separated: Crohn's disease (green circles), SpA without chronic inflammation (blue circles), SpA with chronic inflammation (yellow circles) and controls (red circles).

Identification of genes whose differential regulation is common to both SpA with chronic gut inflammation and Crohn's disease

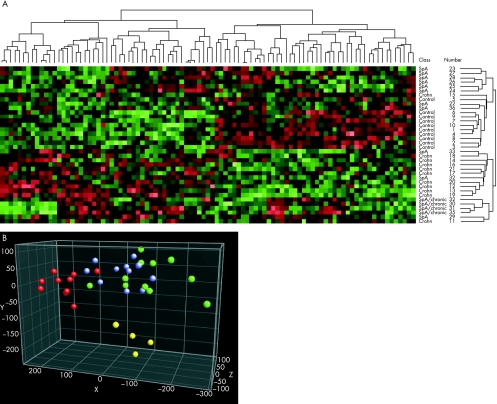

With an independent t test, we identified 123 genes that were expressed differentially between patients with Crohn's disease and controls (p<0.01). With this set, we were unable to distinguish patients with SpA from controls, although three of four of the patients with SpA with chronic gut inflammation clustered together, indicating the presence of changes similar to those observed in patients with Crohn's disease. Thus, it was logical to screen for genes modulated commonly in patients with Crohn's disease and controls on the one hand, and patients with SpA with chronic gut inflammation and controls on the other hand. To include a larger number of genes in this analysis, the level of significance was lowered from p<0.01 to p<0.05. This led to the identification of two sets of genes whose expression pattern differentiates patients with Crohn's disease from controls (p<0.05, n = 630) and those with SpA from controls (p<0.05, n = 464). The significance level for comparison of patients with SpA and controls was determined by analysis of variance, in which patients with SpA and chronic gut inflammation were defined as a distinct group. The set of 95 genes that were differentially expressed in patients with Crohn's disease and in those with SpA distinguished the three disease groups (fig 2A, table 2). In addition, patients with SpA and chronic gut inflammation clustered together and were more related to the cluster of patients with Crohn's disease than to the cluster of controls or patients with SpA, but remained a separate entity (fig 2A). Using this set of 95 genes, principal component analysis (another way of representing the data) clearly differentiates our patient groups (fig 2B). We attempted to identify the set of genes responsible for Crohn's disease that are also implicated in SpA in order to establish the genes that may render these people more susceptible to Crohn's disease.

Figure 2 (A) Complete linkage clustering based on a set of 95 genes whose expression is deviant in patients with Crohn's disease (Crohn) and in those with spondyloarthropathy (SpA) and chronic gut inflammation as compared with healthy controls. Two main clusters mark an SpA–control cluster and a Crohn's disease–SpA with chronic inflammation cluster. (B) Principal component analysis view with a set of 95 genes whose expression is deviant in patients with Crohn's disease and in those with SpA and chronic gut inflammation. Crohn's disease (green circles), SpA without chronic inflammation (blue circles), SpA with chronic inflammation (yellow circles) and controls (red circles).

Table 2 Ninety five ESTs that cluster patients with Crohn's disease and those with SpA and chronic gut inflammation.

| Accession | Unigene | Symbol | Gene description | Cytogenetic location | Expression in CD/SpA chronic | Marker | Score | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H81904 | Hs.14779 | ACAS2 | Acetyl‐coenzyme A synthetase 2 (ADP forming) | 20q11.22 | ↓ | |||

| AI758270 | ↓ | |||||||

| R20596 | Hs.101359 | C6orf32 | Chromosome 6 open reading frame 32 | 6p22.3–p21.32 | D6S2439 | LOD 2.6 | Barmada et al25 | |

| AI349525 | Hs.121692 | FLJ34790 | Hypothetical protein FLJ34790 | 17p13.1 | ↓ | |||

| AI445844 | Hs.444422 | PDK3 | Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase, 3 | Xq22 | ↓ | DXS1226‐DXS1214 | LOD 2.0 | van Heel et al26 |

| H56656 | Hs.282958 | FLJ13611 | 5q12.3 | ↓ | ||||

| N22829 | Hs.299055 | GDI2 | GDP dissociation inhibitor 2 | 10p15 | ↓ | |||

| AI274555 | Hs.170568 | TATDN1 | TatD DNase domain containing | 8q24.13 | D8S198 | NPL 2.47 | Vermeire et al27 | |

| H61436 | Hs.184668 | SNX24 | Sorting nexin 24 | 5q23.2 | ||||

| H15751 | Hs.30634 | PARP16 | Poly (ADP‐ribose) polymerase family, member 16 | 15q22.31 | ↓ | |||

| H87107 | Hs.216354 | RNF5 | Ring finger protein 5 | 6p21.3 | ↓ | D6S1281‐D6S1019 | LOD 2.3 | Rioux et al28 |

| AI680066 | ||||||||

| AI191504 | Hs.510373 | AK7 | Adenylate kinase 7 | 14q32.2 | ↓ | |||

| R17390 | Hs.80132 | SNX15 | Sorting nexin 15 | 11q12 | ||||

| AA812701 | Hs.343631 | LOC340178 | Hypothetical protein LOC340178 | 6q27 | ||||

| AA825971 | Hs.209561 | KIAA1715 | 2q31 | |||||

| AA291593 | Hs.3402 | SLC39A11 | Solute carrier family 39 (metal ion transporter) member 11 | 17q24.3–q25.1 | ||||

| Hs.118836 | MB | Myoglobin | 22q13.1 | D22S689 | LOD 1.5 | Barmada et al25 | ||

| AA420968 | Hs.98323 | C6orf112 | Chromosome 6 open reading frame 112 | 6q21 | ||||

| R08643 | Hs.350268 | IRF2BP2 | Interferon regulatory factor 2 binding protein 2 | 1q42.3 | ||||

| T83584 | Hs.115945 | MANBA | Mannosidase, βA, lysosomal | 4q22–q25 | D4S406 | NPL 2.17 | Vermeire et al27 | |

| AA481482 | Hs.67928 | ELF3 | E74‐like factor 3 (ets domain transcription factor, epithelial specific ) | 1q32.2 | ||||

| T78477 | Hs.206770 | ZNF297 | Zinc finger protein 297 | 6p21.3 | D6S121‐D6S1019 | LOD 2.3 | Rioux et al28 | |

| H27674 | Hs.238465 | DAB2IP | DAB2‐interacting protein | 9q33.1–q33.3 | ||||

| R13194 | Hs.32935 | BRF1 | BRF1 homologue, subunit of RNA polymerase III transcription initiation factor IIIB | 14q | ||||

| R98758 | Hs.380474 | FLJ32731 | Hypothetical protein FLJ32731 | 8p11.1 | ||||

| H96900 | Hs.356467 | MGC2747 | MGC2747 | 19p13.11 | ||||

| N62199 | Hs.375193 | KIF1B | Kinesin family member 1B | 1p36.2 | ↓ | D1S1597 | LOD 3.01 | Cho et al29 |

| R51052 | Hs.296169 | SPHAR | S‐phase response (cyclin‐related) | 1q42.11–q42.3 | ↓ | |||

| AI286348 | Hs.443728 | SH3RF2 | SH3 domain containing ring finger 2 | 5q32 | ||||

| R17478 | Hs.497159 | PIG13 | Proliferation‐inducing protein 13 | 1q25 | ||||

| AI916359 | Hs.205842 | ATP2C2 | Secretory pathway calcium ATPase 2 | 16q24.1 | ||||

| H19034 | Hs.5300 | BLCAP | Bladder cancer‐associated protein | 20q11.2–q12 | ||||

| N39050 | Hs.93825 | FLJ39784 fis | Homo sapiens cDNA FLJ39784 fis, clone SPLEN2002314 | |||||

| R13544 | Hs.7540 | FBXL3A | F‐box and leucine‐rich repeat protein 3A | 13q22 | ↓ | |||

| AI286163 | Hs.122428 | ↓ | ||||||

| R07321 | Hs.464137 | ACOX1 | Acyl‐coenzyme A oxidase 1, palmitoyl | 17q24–17q25 | ↓ | |||

| R12168 | Hs.96870 | STAU2 | Staufen, RNA‐binding protein, homologue 2 (Drosophila) | 8q13–q21.1 | ↓ | |||

| H85472 | Hs.75789 | NDRG1 | N‐myc downstream‐regulated gene 1 | 8q24.3 | ↓ | |||

| AA513663 | ↓ | |||||||

| R97820 | Hs.325568 | ZC3HAV1 | Zinc finger CCCH type, antiviral 1 | 7q34 | ↓ | |||

| N62837 | Hs.48647 | ILT7 | Leucocyte Ig‐like receptor, subfamily A (without TM domain), 4 | 19q13.4 | ↓ | |||

| AA019615 | Hs.145469 | UCHL5 | Ubiquitin carboxyl‐terminal hydrolase L5 | 1q32 | ↓ | |||

| AI809092 | ↓ | |||||||

| AA758064 | Hs.401400 | |||||||

| AI219353 | Hs.89387 | CASC2 | Cancer susceptibility candidate 2 | 10q26.11 | ↓ | |||

| AI698801 | Hs.202187 | |||||||

| R12632 | Hs.109706 | HN1 | Haematological and neurological expressed 1 | 17q25.1 | ||||

| AA468418 | ||||||||

| Hs.28777 | HIST1H2AC | Histone 1, H2ac | 6p21.3 | D6S2439 | LOD 2.6 | Barmada et al25 | ||

| H23734 | Hs.522584 | TMSB4X | Thymosin, β4, X linked | Xq21.3–q22 | ||||

| H75688 | Hs.197015 | SNX7 | Sorting nexin 7 | 1p21.3 | ||||

| N63669 | Hs.81541 | TRIO | Triple functional domain (PTPRF interacting) | 5p15.1–p14 | ||||

| AI819016 | ↑ | |||||||

| AI831827 | Hs.211194 | ARFGEF2 | ADP‐ribosylation factor guanine nucleotide exchange factor 2 | 20q13.13 | ||||

| AI923299 | Hs.213456 | LOC158730 | Hypothetical LOC158730 | Xp21.1 | ↑ | |||

| AI286257 | Hs.124553 | ZNF263 | Zinc finger protein 263 | 16p13.3 | ||||

| AI863417 | Hs.208726 | RUNX1 | Runt‐related transcription factor 1 (acute myeloid leukaemia 1; aml1 oncogene) | 21q22.3 | ↑ | |||

| AI921132 | ||||||||

| AI274438 | ↑ | |||||||

| AI289775 | Hs.387091 | EST, weakly similar to 0412263A Ig G2 pFc' PIG Gm | ↑ | |||||

| AI345173 | ||||||||

| AI928384 | ||||||||

| AA490519 | Hs.16165 | CDNA clone IMAGE:5286005 | ||||||

| AI696951 | Hs.355460 | CDNA: FLJ21763 fis | ||||||

| AI339536 | Hs.348436 | Homo sapiens, clone IMAGE:5286812, mRNA | ||||||

| AI245190 | ||||||||

| AI261428 | Hs.145523 | |||||||

| AI809310 | Hs.210385 | HERC1 | Hect domain and RCC1 (CHC1)‐like domain 1 | 15q22 | ||||

| AI831536 | Hs.413608 | IL12RB2 | Interleukin 12 receptor, β2 | 1p31.3–p31.2 | ||||

| T79944 | ↑ | |||||||

| AA480677 | Hs.161954 | Homo sapiens, clone IMAGE:4865533 | ↑ | |||||

| AA009461 | Hs.172210 | MUF1 | MUF1 protein | 1p34.1 | ↑ | D1S197 | NPL 2.07 | Vermeire et al27 |

| R61783 | Hs.5097 | SYNGR2 | Synaptogyrin 2 | 17q25.3 | ↑ | |||

| AI282992 | Hs.2704 | GPX2 | Glutathione peroxidase 2 (gastrointestinal) | 14q24.1 | ↑ | |||

| W65310 | ||||||||

| AA588676 | Hs.162575 | PDLIM3 | PDZ and LIM domain 3 | 10q22.3–q23.2 | ||||

| AI811147 | ↑ | |||||||

| AI357718 | ||||||||

| N58523 | Hs.137274 | |||||||

| W74496 | ↑ | |||||||

| AI352320 | ↑ | |||||||

| AI280708 | Hs.7155 | LOC129607 | Thymidylate kinase family LPS‐inducible member | 2p25.2 | ||||

| AI815599 | Hs.90744 | PSMD11 | Proteasome (prosome, macropain) 26S subunit, non‐ATPase, 11 | 17q11.2 | ||||

| AI718161 | ||||||||

| N98921 | Hs.85844 | TPM3 | Tropomyosin 3 | 1q21.2 | D1S305 | NPL 2.97 | Vermeire et al27 | |

| AI367201 | Hs.127496 | HSPC135 | HSPC135 protein | 3q13.2 | ||||

| AA425545 | Hs.104613 | RP42 | RP42 homologue | 3q26.3 | ||||

| H44213 | Hs.374986 | Hypothetical gene supported by BC031266 | ||||||

| N58936 | Hs.339283 | NCOA7 | Nuclear receptor coactivator 7 | 6q22.32 | ||||

| N90208 | Hs.344478 | FLJ32440 | Hypothetical protein FLJ32440 | 8q24.13 | D8S198 | NPL 2.47 | Vermeire et al27 | |

| AA427403 | Hs.366 | IFITM1 | Interferon‐induced transmembrane protein 1 (9‐27) | 11p15.5 | ||||

| R25648 | Hs.23920 | PI4K2B | Phosphatidylinositol 4‐kinase type IIβ | 4p15.2 | ||||

| N93265 | Hs.75428 | SOD1 | Superoxide dismutase 1, soluble (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis 1 (adult)) | 21q22.11 | ||||

| H99865 | Hs.91954 | NR2F2 | Nuclear receptor subfamily 2, group F, member 2 | 15q26 | ||||

BRF1, butyrate response factor 1; CD, Crohn's disease; Zo1, zonula occludens‐1; DAB2, disabled homolog 2; Dlg, discs‐large protein; EST, expressed sequence tag; Ig, immunoglobulin; LIM, Lin‐11, ls1‐1, Mec‐3; LOD, logarithm of the ratio of the odds that two loci are linked; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; NPL, non‐parametric LOD score; PSD, postsynaptic density protein; SpA, spondyloarthritis.

Genes with aberrant expression in patients with Crohn's disease and in those with SpA and chronic gut inflammation (↓ down regulated and ↑ up regulated as compared with the controls and those with SpA; p<0.05).

Genetic markers are cited for genes that are located within or near (5 cM) one of the Crohn's disease locus, together with the score supporting linkage of the loci.

Genes within the Crohn's disease–SpA chronic cluster

Table 2 shows the genes whose expression is aberrant in Crohn's disease and in SpA with chronic gut inflammation. Among them, two genes had already been described in the context of Crohn's disease. Acyl‐coenzyme A oxidase 1 (ACOX1), which is the first enzyme of the fatty acid β‐oxidation pathway, donates electrons directly to molecular oxygen, thereby producing hydrogen peroxide. The enzymatic activity of ACOX1 was diminished in both inflamed and non‐inflamed areas in patients with Crohn's disease.18 Our observation of down regulation of the ACOXI transcript corroborates this report and indicates a fault at the level of transcription or mRNA stability.

Glutathione peroxidase 2 (gastrointestinal glutathione peroxidase) is one of the four types of selenium‐dependent glutathione peroxidases. Its exclusive expression in the gastrointestinal tract indicates that it functions as a barrier against the absorption of dietary hydroperoxides and protects against damage from endogenously formed hydroxyl peroxides. Its activity is increased in patients with ulcerative colitis in the active and in the remission stages.19 Patients with Crohn's disease have increased plasma levels of gastrointestinal glutathione peroxidase.20 We found that this gene is overexpressed in normal colon tissue in patients with Crohn's disease and in those with SpA and a history of chronic gut inflammation; thus, it can act as a marker expressed at non‐pathological sites in the intestine of patients with Crohn's disease and of those in SpA susceptible to Crohn's disease.

Discussion

Clinical study of intestinal abnormalities in patients with SpA has previously relied on cytokine profiles and immunological changes. In addition to analysing every protein, genomewide transcript profiles can be analysed by microarrays. Global gene expression analysis in non‐inflamed colon tissue was used to find genes that are differentially expressed in patients with Crohn's disease and in those with SpA and a history of chronic gut inflammation. Previous studies on gene expression in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) have focused on biopsy specimens of actively inflamed tissues.21,22,23 The use of samples from non‐inflamed areas from patients with Crohn's disease offers the possibility of identifying early markers for Crohn's disease, which would permit prediction of the evolution to Crohn's disease in patients with SpA. Moreover, changes in the expression of genes that are regulated during inflammation would be more prominent than the subtle changes in non‐inflammatory genes. It cannot be ruled out, however, that this procedure will also pick up genes whose differential expression is a consequence and not a cause of the disease. Additionally, looking at basal gene expression may enable us to consider genetic influences, as gene expression is highly heritable.24 Therefore, future studies on markers for Crohn's disease should concentrate primarily on genes that are located near one of the known loci for Crohn's disease (table 2). Genes located within a region linked to Crohn's disease or IBD in general (if multipoint linkage was carried out), or within 5 cM of the markers that are linked to Crohn's disease or IBD (in case of two‐point linkage), should be considered first. By using a model for early Crohn's disease when identifying Crohn's disease susceptibility genes, investigators can circumvent the heterogeneity of the disease, as only a small number of Crohn's disease genes will be implicated in patients with SpA.

Array analysis is a procedure for studying the expression of many genes in a limited number of samples. As the number of genes explored is usually large, this can lead to false‐positive results. Nevertheless, array analysis enables us to explore gene expression with different computational tools. To confirm the importance of a set of genes associated with a phenotype, complementary techniques such as quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR are mandatory. Thus, arrays are not simply a way to find single differentially regulated genes; they can be used to compare global gene expression in distinct groups.

We show that patients with SpA have an aberrant gene expression profile when compared with healthy controls, indicating that changes in gene expression in the colon of patients with SpA is a biologically relevant concept. We identified a set of genes that are differentially expressed in both patients with Crohn's disease and those with SpA who are at higher risk of developing Crohn's disease. On the basis of the expression of these 95 genes, patients with SpA having subclinical chronic gut inflammation cluster with patients with Crohn's disease, confirming the clinical association between the two inflammatory disorders. We suggest a number of candidate genes for mutation screening. We are currently verifying a selection of genes by quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR and exploring the association of genes that are differentially expressed in patients with Crohn's disease and in those with SpA with a history of chronic gut inflammation, to find early (genetic) markers for Crohn's disease in patients with SpA.

Abbreviations

ACOXI - Acyl‐coenzyme A oxidase 1

EST - expressed sequence tag

IBD - inflammatory bowel disease

PCR - polymerase chain reaction

SpA - spondyloarthropathy

Footnotes

Funding: This study was supported by a concerted action grant GOA2001/12051501 from Ghent University, Belgium; grants from the Flemish Society of Crohn and Ulcerative Colitis; the Flemish Society of Gastroenterology; and the Flanders Interuniversity Institute for Biotechnology (VIB).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: The regional ethics committee (project 2004/242) approved the study. All patients signed an informed consent form.

References

- 1.Davis P, Thomson A B, Lentle B C. Quantitative sacroiliac scintigraphy in patients with Crohn's disease. Arthritis Rheum 197821234–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scott W W, Jr, Fishman E K, Kuhlman J E, Caskey C I, O'Brien J J, Walia G S.et al Computed tomography evaluation of the sacroiliac joints in Crohn disease. Radiologic/clinical correlation. Skeletal Radiol 199019207–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mielants H, Veys E M, Cuvelier C, De Vos M, Goemaere S, De Clercq L.et al The evolution of spondyloarthropathies in relation to gut histology. II. Histological aspects. J Rheumatol 1995222273–2278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Vos M, Mielants H, Cuvelier C, Elewaut A, Veys E. Long‐term evolution of gut inflammation in patients with spondyloarthropathy. Gastroenterology 19961101696–1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Demetter P, Baeten D, De Keyser F, De Vos M, Van Damme N, Verbruggen G.et al Subclinical gut inflammation in spondyloarthropathy patients is associated with upregulation of the E‐cadherin/catenin complex. Ann Rheum Dis 200059211–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elewaut D, De Keyser F, Van Den Bosch F, Lazarovits A I, De Vos M, Cuvelier C.et al Enrichment of T cells carrying beta7 integrins in inflamed synovial tissue from patients with early spondyloarthropathy, compared to rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 1998251932–1937. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Demetter P, Van Huysse J A, De Keyser F, Van Damme N, Verbruggen G, Mielants H.et al Increase in lymphoid follicles and leukocyte adhesion molecules emphasizes a role for the gut in spondyloarthropathy pathogenesis. J Pathol 2002198517–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elewaut D, De Keyser F, Cuvelier C, Lazarovits A I, Mielants H, Verbruggen G.et al Distinctive activated cellular subsets in colon from patients with Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol 199833743–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baeten D, Demetter P, Cuvelier C A, Kruithof E, Van Damme N, De Vos M.et al Macrophages expressing the scavenger receptor CD163: a link between immune alterations of the gut and synovial inflammation in spondyloarthropathy. J Pathol 2002196343–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bjarnason I, Helgason K O, Geirsson A J, Sigthorsson G, Reynisdottir I, Gudbjartsson D.et al Subclinical intestinal inflammation and sacroiliac changes in relatives of patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Gastroenterology 20031251598–1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laukens D, Peeters H, Marichal D, Vander Cruyssen B, Mielants H, Elewaut D.et alCARD15 gene polymorphisms in patients with spondyloarthropathies identify a specific phenotype previously related to Crohn's disease. Ann Rheum Dis 200464930–935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dougados M, van der Linden S, Juhlin R, Huitfeldt B, Amor B, Calin A.et al The European Spondylarthropathy Study Group preliminary criteria for the classification of spondylarthropathy. Arthritis Rheum 1991341218–1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mielants H, Veys E M, De Vos M, Cuvelier C, Goemaere S, De Clercq L.et al The evolution of spondyloarthropathies in relation to gut histology. I. Clinical aspects. J Rheumatol 1995222266–2272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mielants H, Veys E M, Cuvelier C, De Vos M, Goemaere S, De Clercq L.et al The evolution of spondyloarthropathies in relation to gut histology. III. Relation between gut and joint. J Rheumatol 1995222279–2284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Vos M. Ileocolonoscopy in seronegative spondylarthropathy. Gastroenterology 198996339–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cuvelier C, Barbatis C, Mielants H, De Vos M, Roels H, Veys E. Histopathology of intestinal inflammation related to reactive arthritis. Gut 198728394–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Puská L G, Zvara A, Hackler L, Jr, Van Hummelen P. RNA amplification results in reproducible microarray data with slight ratio bias. Biotechniques 2002321330–4, 1336, 1338, 1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aimone‐Gastin I, Cable S, Keller J M, Bigard M A, Champigneulle B, Gaucher P.et al Studies on peroxisomes of colonic mucosa in Crohn's disease. Dig Dis Sci 1994392177–2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beno I, Staruchova M, Volkovova K. Ulcerative colitis: activity of antioxidant enzymes of the colonic mucosa. Presse Med 1997261474–1477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tuzun A, Erdil A, Inal V, Aydin A, Bagci S, Yesilova Z.et al Oxidative stress and antioxidant capacity in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Biochem 200235569–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lawrance I C, Fiocchi C, Chakravarti S. Ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease: distinctive gene expression profiles and novel susceptibility candidate genes. Hum Mol Genet 200110445–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dooley T P, Curto E V, Reddy S P, Davis R L, Lambert G W, Wilborn T W.et al Regulation of gene expression in inflammatory bowel disease and correlation with IBD drugs: screening by DNA microarrays. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2004101–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Costello C M, Mah N, Hasler R, Rosenstiel P, Waetzig G H, Hahn A.et al Dissection of the inflammatory bowel disease transcriptome using genome‐wide cDNA microarrays. PLoS Med 20052e199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morley M, Molony C M, Weber T M, Devlin J L, Ewens K G, Spielman R S.et al Genetic analysis of genome‐wide variation in human gene expression. Nature 2004430743–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barmada M M, Brant S R, Nicolae D L, Achkar J P, Panhuysen C I, Bayless T M.et al A genome scan in 260 inflammatory bowel disease‐affected relative pairs. Inflamm Bowel Dis 200410513–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Heel D A, Fisher S A, Kirby A, Daly M J, Rioux J D, Lewis C M. Inflammatory bowel disease susceptibility loci defined by genome scan meta‐analysis of 1952 affected relative pairs. Hum Mol Genet 200413763–70 Epub 2004 Feb 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vermeire S, Rutgeerts P, Van Steen K, Joossens S, Claessens G, Pierik M.et al Genome wide scan in a Flemish inflammatory bowel disease population: support for the IBD4 locus, population heterogeneity, and epistasis. Gut 200453980–986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rioux J D, Silverberg M S, Daly M J, Steinhart A H, McLeod R S, Griffiths A M.et al Genomewide search in Canadian families with inflammatory bowel disease reveals two novel susceptibility loci. Am J Hum Genet 2000661863–70 Epub 2000 Apr 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cho J H, Nicolae D L, Ramos R, Fields C T, Rabenau K, Corradino S.et al Linkage and linkage disequilibrium in chromosome band 1p36 in American Chaldeans with inflammatory bowel disease. Hum Mol Genet 200091425–1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]