Abstract

DGUOK [dG (deoxyguanosine) kinase] is one of the two mitochondrial deoxynucleoside salvage pathway enzymes involved in precursor synthesis for mtDNA (mitochondrial DNA) replication. DGUOK is responsible for the initial rate-limiting phosphorylation of the purine deoxynucleosides, using a nucleoside triphosphate as phosphate donor. Mutations in the DGUOK gene are associated with the hepato-specific and hepatocerebral forms of MDS (mtDNA depletion syndrome). We identified two missense mutations (N46S and L266R) in the DGUOK gene of a previously reported child, now 10 years old, who presented with an unusual revertant phenotype of liver MDS. The kinetic properties of normal and mutant DGUOK were studied in mitochondrial preparations from cultured skin fibroblasts, using an optimized methodology. The N46S/L266R DGUOK showed 14 and 10% residual activity as compared with controls with dG and deoxyadenosine as phosphate acceptors respectively. Similar apparent negative co-operativity in the binding of the phosphate acceptors to the wild-type enzyme was found for the mutant. In contrast, abnormal bimodal kinetics were shown with ATP as the phosphate donor, suggesting an impairment of the ATP binding mode at the phosphate donor site. No kinetic behaviours were found for two other patients with splicing defects or premature stop codon. The present study represents the first characterization of the enzymatic kinetic properties of normal and mutant DGUOK in organello and our optimized protocol allowed us to demonstrate a residual activity in skin fibroblast mitochondria from a patient with a revertant phenotype of MDS. The residual DGUOK activity may play a crucial role in the phenotype reversal.

Keywords: deoxyguanosine kinase, enzymatic assay, mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) depletion, revertant phenotype, skin fibroblast

Abbreviations: dA, deoxyadenosine; dCK, deoxycytidine kinase; dG, deoxyguanosine, DGUOK, dG kinase; mtDNA, mitochondrial DNA; MDS, mtDNA depletion syndrome; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; qPCR, quantitative PCR; RT, reverse transcriptase; TK2, thymidine kinase 2

INTRODUCTION

MDS [mtDNA (mitochondrial DNA) depletion syndrome] is a quantitative disorder characterized by a variable tissue-specific reduction in mtDNA copy number. Myopathic (OMIM 609560) and hepatocerebral (OMIM 251880) forms are the main clinical presentations. The onset usually occurs in infancy or early childhood, but may be delayed into childhood with prolonged survival [1]. MDS patients with liver as the most or only affected organ usually die of severe liver failure before 1 year of age [2–4]. We reported previously the first case of a progressive reversion of the clinical and molecular phenotype in a child (patient 1) with liver-restricted MDS [1]. MDS is an autosomal recessive disorder and five nuclear genes are known to be involved in the pathogenesis of MDS in infancy or childhood: DGUOK [dG (deoxyguanosine) kinase] [5], TK2 (thymidine kinase 2) [6] and SUCLA2 (succinate-CoA ligase, ADP-forming, beta subunit) [7] involved in the maintenance of the mitochondrial dNTP pool, POLG [polymerase (DNA directed), gamma] involved in mtDNA replication [8] and MPV17 controlling mtDNA maintenance [9]. In mammal cells and tissues, DGUOK and TK2 are the two rate-limiting enzymes involved in the first step of the mitochondrial salvage pathway of the purine and pyrimidine deoxyribonucleosides respectively. Mutations in the DGUOK gene have been identified in patients with hepatic or hepatocerebral forms of MDS [3–5,10]. For this reason, we decided to study this gene in order to identify possible molecular anomalies in patient 1.

The human DGUOK is localized to chromosome band 2p13 and spans nearly 32 kb with seven exons. For this gene, five alternative splice variants encoding four different protein isoforms have been described. Variant 1 represents the longest transcript (NM_0890916) and encodes the longest 277-amino-acid isoform. Human DGUOK (nucleoside triphosphate: deoxyguanosine 5′-phosphotransferase; EC 2.7.1.113) is a dimer of two identical subunits of 30 kDa. The three-dimensional structure of the human DGUOK monomer has been reported [11], providing an explanation for the substrate specificity of the enzyme. DGUOK selectively phosphorylates purine deoxynucleosides and their analogues, with the highest efficiency for dG, using ATP and UTP as the most efficient phosphate donors. DGUOK belongs to the family of deoxynucleoside kinases, which includes mammal dCK (deoxycytidine kinase) and TK2 and the Drosophila melanogaster deoxynucleoside kinase. The high sequence homology between DGUOK and cytosolic dCK (45%) [11] explains why dCK has an overlapping substrate specificity with DGUOK [12,13]. DGUOK activity measurements have been described in cell and tissue extracts, including human skin fibroblasts [12]. Kinetic parameters of the enzyme have been assessed with DGUOK purified from bovine liver [14,15] or brain [12] and with human recombinant DGUOK [16].

To date, ten different DGUOK mutations have been identified in 17 MDS families with one or more affected siblings [3–5,10,17,18]. A partial defect of DGUOK activity has been reported in the liver of one patient who presented with isolated liver failure and carried two compound heterozygous missense mutations [3]. Site-directed mutagenesis has been used to study the consequences of these two missense mutations on the activity of recombinant enzymes [19].

In the present study, two different missense mutations were identified in patient 1. To find out if these mutant enzymes could be involved in the mechanism responsible for the reversal of the MDS phenotype, we optimized the DGUOK activity assay for cultured skin fibroblast mitochondria. We determined the kinetic parameters of the wild-type and mutant enzymes in organello and showed that the DGUOK mutant enzymes from patient 1 have a markedly higher residual activity compared with the severe deficiency of two other patients with splicing defects or premature stop codon. DGUOK activity in mitochondria from skin fibroblasts correlated with the course of the disease and the type of mutations in DGUOK.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Case reports

Patient 1

This boy was born to unrelated French parents with no clinical relevant family history. The initial patient history until age 28 months was previously reported [2]. He presented with infantile cholestasis and progressive liver fibrosis due to mtDNA depletion (85% at 12 months of age). For this liver MDS without extrahepatic clinical involvement at age 28 months, a liver transplantation was initially discussed to correct the progressive liver failure in case of worsening. Surprisingly however, the patient displayed a spontaneous gradual improvement of his liver function with continuous increment of clotting factors since 32 months of age. At the age of 46 months, clinical, biochemical and molecular follow-up demonstrated an almost complete reversion of the MDS [1].

During the following months, liver tests continued to improve [1]. At 10 years of age, the child is now clinically healthy without any treatment or special regimen, yet hepatic ultrasonography showed the same heterogeneous liver compared with the previous examinations. Kidney and cardiac function, and cerebral MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) showed no abnormalities. Clotting factors remained stable (II 64%, V 73%, VII 73%) as well as prothrombine time (70% of the normal value). The liver-specific enzyme, ALAT (alanine aminotransferase), remained slightly increased (104 units/l; normal: 10–65). Lactate level was normal after fasting and feeding (1.1 and 2.0 mmol/l respectively; normal <2.2). Lactate/pyruvate ratios were also normal (<12; normal <20). A second child, a boy, was born unaffected. Informed consent for the present study was obtained from the parents.

Patient 2

This boy presented with a typical form of hepatocerebral MDS. He was the second child of healthy young unrelated French parents without family history. A first child, a boy, died of a haemorrhagic syndrome of unknown aetiology at 10 days of age. At birth, the baby presented with sub-ictere, hypoglycaemia and lactic acidosis. At 2 months of age, he became hypotrophic and developed progressive axial hypotonia and roving eye movements. Visual evoked potentials were markedly abnormal. MRI did not show evident abnormality of the white matter. Electron microscopy of the liver revealed steatosis and an accumulation of abnormal pleomorphic mitochondria with abnormal cristae. Enzymatic measurements of the respiratory chain complexes revealed a specific severe defect of the activities of the complexes I, III and IV (5, 7 and 7% of the mean control values respectively) related to mtDNA depletion (85%) (‘other case’ in [2]). In contrast, complex II activity was at the upper limit of the normal range. Subsequently, liver function rapidly worsened. Neurological status deteriorated rapidly with major hypotonia and the patient died at 3 months of age. Informed parental consent was obtained for the present study.

Patient 3

The third child of consanguineous Moroccan parents presented immediately after birth with hypoglycaemia and lactic acidosis. Liver function tests revealed cholestasis and mild cytolysis. Neurological and cardiac functions were normal. At 1 month of age, there was a rapid evolution towards cytolysis, coagulopathy, fasting intolerance and severe lactic acidosis. Depletion of mtDNA in liver (80%) was demonstrated, associated with defects of mtDNA-related respiratory chain complexes (15, 20 and 30% of the mean control values for the complexes I, III and IV respectively). The patient died at 2 months of age of liver failure. Informed consent for the present study was obtained from the parents.

Cell cultures and mitochondria preparation

Fibroblasts from forearm skin explants obtained from patients, family members and controls were cultured in Ham's F10 medium supplemented with 12% (v/v) fetal calf serum, with penicillin, streptomycin and amphotericin B and 50 mg/l of uridine. Cells were routinely cultured in plastic flasks (T175) at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air. Cultures were checked for mycoplasma infection prior to all experiments.

Mitochondria-enriched preparations from cultured fibroblasts were obtained as described previously [20,21]. For liver, the method for preparation of mitochondria was adapted from Rustin et al. [22], using a homogenization buffer containing 40 mM KCl, 2 mM EGTA, 20 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.4) and 1 mg/ml of BSA. Mitochondria were washed once in their respective buffers and pelleted for 15 min at 11000 g. Pellets were resuspended in a minimal volume of buffer and kept in aliquots at −80 °C. Protein concentration was measured by the bicinchoninic acid method.

Enzymatic measurements

Enzymatic activities of the respiratory chain complexes were measured in liver homogenates and in mitochondria-enriched preparations from cultured fibroblasts as reported previously [21].

The DGUOK activity was measured radiochemically in mitochondria-enriched preparations from fibroblasts with a procedure based on that described by Ives and Wang [23], using 2′-[8-3H]dG or 2′-[8-3H]dA (deoxyadenosine) (MP Biomedicals) as substrates. Thawed mitochondria were lysed in 50 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.4), 3 mM DTT (dithiothreitol), 1.5 mM PMSF and 0.5% Nonidet P40 (2:1, v/v). The standard reaction mixture contained 75 mM Tris/HCl (pH 8), 5 mM/6 mM ATP/MgCl2, 0.25 mg/ml of BSA, 2 mM DTT and 50 μM 3H-labelled nucleoside (50 GBq/mmol) in a total volume of 50 μl. To exclude possible interference by cytosolic dCK, reactions were conducted in the presence of 2 mM dC (deoxycytidine). One unit is defined as the formation of 1 pmol of product (dAMP or dGMP) per hour per milligram of protein. Assays were initiated by addition of 2.5–7.5 μg of mitochondrial protein per assay and conducted at 37 °C during 16 h for the dA substrate and 18 h for the dG substrate. The amount of deoxyribonucleotides formed was determined by spotting aliquots of 40 μl on Whatman DE-81 anion-exchange papers (20 mm×25 mm) (Fisher Bioblock). The papers were then washed 1×15 min and 1×5 min in 1 mM ammonioformate (Carlo Erba Reagents). The papers were put in 1 ml of elution buffer (0.1 M HCl+0.4 M KCl); 4 ml of Ultima Gold Safe scintillation fluid (PerkinElmer) was added and the radioactive solutions were counted in a Tri-Carb scintillation counter (PerkinElmer). For the measurement of the phosphate acceptor constants, a wide concentration range of each deoxynucleoside was used (0.3–50 μM for dG and 0.6–50 μM for dA). For the measurement of phosphate donor constants, ATP/MgCl2 was varied (0.25/0.30 to 7.5/9 mM), while dG or dA was kept at 20 μM. For mitochondria-enriched preparations from liver, the same procedure was used with the following modifications: 1 mM/1.2 mM ATP/MgCl2 in the standard reaction mixture, 15 μg of protein per assay and assays were conducted during 6 h for the dA substrate and 4 h for the dG substrate. The data were analysed by the Sigma Plot 9.0 Enzyme Kinetic Module (Systat Software).

Molecular investigations

For mtDNA quantification, continuous real-time qPCR (quantitative PCR), with the fluorescent SYBR Green I double-strand DNA-specific dye, was used to determine the copy number for two mitochondrial genes [ND2 (NADH dehydrogenase 2) and 16 S] and a nuclear gene [ATPsynβ (ATP synthase β)], as described previously [24]. For each gene tested, a standard curve was generated using a serial dilution of the target gene standard PCR product. Controls and patients were included in the same run. The mean of the results obtained from the two different mtDNA probes was used to calculate the mtDNA/nuclear DNA ratio.

For DGUOK mutation analysis, the human chromosome 2 working draft sequence segment (accession number NT_025651) was used to sequence each of the seven exons and their intron/exon boundaries of the propositi and their parents as described by Mandel et al. [5].

For analysis of the DGUOK transcript of patient 2, total RNA was isolated from cultured fibroblasts of the patient and a control as described earlier [25]. In a thin-walled tube, 20 pmol of oligo-dT anchor primer [from the 5′/3′-RACE (rapid amplification of cDNA ends) kit of Roche] was annealed with 1 μg of total RNA in a volume of 5 μl by incubation at 70 °C for 5 min, followed by a quick chill at 4 °C for 5 min and a hold on ice. To obtain single-stranded cDNA, reverse transcription of RNA was performed with the ImProm-II RT (reverse transcriptase) kit (Promega) in a volume of 20 μl, as recommended by the supplier. Subsequently, 5 μl of the single-stranded cDNA product was used to amplify DGUOK cDNA with the Thermo-Start PCR master mix from Abgene. The PCRs were performed in a volume of 50 μl with either 50 pmol of the exon 3 (forward) primer 5′-ACTGCCCAAAGTCTTGGAAAC or 50 pmol of the exon 4 (forward) primer 5′-TGGTTCCCTCAGTGACATCGA and 50 pmol of the exon 5–6 junction (reverse) primer 5′-GTGGAGCTTCGTTGTCTTGTG (nt 262–282, 474–494 and 694–714 of the DGUOK cDNA respectively; numbering according to [26]. After an initial denaturation step at 95 °C for 15 min, the samples were subjected to 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 55 °C for 30 s and polymerization at 72 °C for 30 s, and a final polymerization step at 72 °C for 7 min. PCR products were resolved by agarose gel electrophoresis and extracted from the gel with the QIAquick Gel Extraction kit (Qiagen). The gel-extracted products of the PCR with the exon 3 and exon 5–6 junction primers were re-amplified with the same primers. Products of the second PCR were purified with the QIAquick PCR Purification kit (Qiagen) and subjected to DNA sequencing, using the exon 3 primer.

RESULTS

Molecular investigations

DGUOK mutations and RT–PCR analysis

Patient 1 is a compound heterozygote for two missense mutations. The c.137A>G mutation in exon 1 changes a highly conserved asparagine to a serine (N46S) in the P-loop of the protein. The other mutation, c.797T>G in exon 6, changes a leucine to an arginine (L266R) in the C-terminal α-9 helical domain. The mother was carrier of the N46S mutation and the father of the L266R mutation (Supplementary Figure 1A at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/402/bj4020377add.htm). The younger unaffected brother was heterozygous for the N46S mutation. Testing of 100 control subjects did not identify any other carrier of these missense mutations.

Patient 2: the DGUOK gene of patient 2 harboured three new heterozygous base changes (Supplementary Figure 1B): (i) a G to T base change (c.4G>T) immediately downstream of the first ATG initiation codon. The second codon will be TCC instead of GCC, coding a serine instead of alanine (A2S). Alanine to serine is quite a conservative change. Considering that this change affects the N-terminal part of the import sequence, this change will have no major effect on the import of the protein into mitochondria (ExPASy proteomics tool Mitoprot; http://www.expasy.org/tools). Nevertheless, a G base change immediately after the start codon is likely to affect start codon recognition by the ribosome [27]. The ribosome may use the ATG codon further downstream as an alternative, (ii) a G to A base change at the consensus GT splice donor site of intron 1 (c.142+1G>A) and (iii) a G to A base change at the 3′-end of exon 4 (c.591G>A). This substitution does not change the amino acid but may induce splicing anomaly. Mutation analysis of the parent's DNA showed that the patient 2 inherited the A2S and the c.591G>A from his father and the c.142+1G >A from his mother.

To examine whether the G→A mutation at the 3′-end of exon 4 had an effect on intron 4 splicing, we amplified exons 3–5 from fibroblast cDNA of patient 2 and a control with primers corresponding to sequences of exon 3 and the exon 5–6 junction. Two different amplification products were revealed: an approx. 450 bp band of expected size in the control sample and an approx. 300 bp band in the patient sample (Supplementary Figure 2A at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/402/bj4020377add.htm). DNA sequencing of these amplification products demonstrated that the 450 bp fragment from the control sample corresponded to DGUOK exons 3–4–5, while the shorter one from the patient sample corresponded to DGUOK exon 3 directly linked to exon 5 (Supplementary Figure 2A). Thus it appears that the c.591G>A mutation in patient 2 causes skipping of exon 4. To further exclude the presence of a small amount of correctly processed mRNA, we tried to amplify exons 4–5 from the patient cDNA with a primer corresponding to sequences of exon 4 and the exon 5–6 junction primer. Although amplification of control cDNA yielded a DNA fragment with a size expected for the exon 4–5 fragment, the cDNA sample of the patient did not yield any product (Supplementary Figure 2B). Furthermore, these results also show that the transcript from the other allele with the c.142+1G>A is undetectable.

Patient 3 was homozygous for the previously reported 4 bp duplication in exon 6 (c.763_766dupGATT) [3], creating a premature stop codon resulting in a truncated 255-amino-acid non-functional protein [19]. Both parents are carriers of this duplication (Supplementary Figure 1C).

Quantification of mtDNA in fibroblast cultures

Levels of mtDNA were determined by qPCR in fibroblast cultures of the three patients and compared with the levels of three control cultures. Cells were collected at the same passage number. In exponentially growing fibroblast cultures, a relatively mild depletion of mtDNA was observed in the three patients. Residual mtDNA levels in the cultures of patients 1, 2 and 3 were 67, 48 and 65% of the mean for the three control cultures (mtDNA/nuclear DNA=100±12%; range: 77–108%) respectively.

DGUOK enzymatic measurements

To assess the pathogenicity of the DGUOK gene mutations in patient 1 compared with two other patients, we could not use liver directly as the specimen from patient 1 was no longer available. Consequently, we developed an enzymatic assay for mitochondria-enriched preparations from cultured fibroblasts, using a radiochemical analysis. Reaction progress curves showed that the assay was linear in controls for up to 20 h for dA and dG, in the range of 2.5–7.5 μg of mitochondrial protein per assay. Between 2.5 and 5 μg, and 5 and 7.5 μg of mitochondrial protein per assay, the same decrease in the specific activities (units/mg) was observed (12 and 13% with dA and dG respectively). Nonlinear reaction velocity versus amount of enzyme preparation per assay can result from a number of factors [28], such as the presence of contaminating inhibitors or instability of the enzyme under the assay conditions. All data are shown for an input of 5 μg of protein per assay. Reproducibility was 11% between days (n=12), using replicate lysed samples, frozen in small aliquots and assayed on different days over a period of 2 months. DGUOK activity was stable for at least 1 year at −80 °C.

As a second step, we measured the specific activities and we characterized the kinetic properties of the mutant enzymes compared with the wild-type enzyme with dG or dA as phosphate acceptors and ATP as phosphate donor.

Specific activities: patients

Mitochondria of exponentially growing fibroblasts from patient 3 (c.763_766dupGATT) showed a very low activity with both dG and dA. Residual activity was 2.6 and 1% of the mean control value with dG and dA as the phosphate acceptors respectively (Table 1). Also for patient 2 with splice mutations, a severe decrease in the catalytic rate was observed: 2.7 and 1.2% of the mean control activity with dG and dA as the phosphate acceptors respectively (Table 1). In contrast, for patient 1 (N46S/L266R) the DGUOK residual activity was 14 and 10% of the mean control activity with dG and dA as the phosphate acceptors respectively (Table 1). DGUOK activity in mitochondria from liver of patients 2 and 3 was reduced by 98% compared with two normal controls. As mentioned earlier, liver samples were no longer available from patient 1.

Table 1. Specific activities of human wild-type and mutant DGUOK enzymes with the phosphate acceptors.

Samples containing 5 μg of mitochondrial protein were assayed under standard conditions (see the Subjects and methods section). The phosphate acceptor concentrations were 50 μM for both dG and dA. The ATP/MgCl2 concentration was fixed at 5 mM/6 mM. For patients and carriers, assays were performed on two different mitochondria-enriched preparations and mean values are shown with the range in parentheses. V is given in picomoles of dG or dA phosphorylated per hour per milligram of protein. Also shown is the percentage of the mean control value.

| V50 μM | ||

|---|---|---|

| dG | dA | |

| Controls (up to 1 year of age) | ||

| Mean | 769 | 2145 |

| Range (n) | 670–905 (6) | 1580–2825 (6) |

| Patients | ||

| Patient 1 (N46S, L266R) | 107 (105–110) (14%) | 214 (197–231) (10%) |

| Patient 2 (c.142+1G>A, c.591G>A) | 21 (16–27) (2.7%) | 26 (25–27) (1.2%) |

| Patient 3 (c.763_766dupGATT) | 20 (4–36) (2.6%) | 22 (17–27) (1%) |

| Controls (36–42 years of age) | ||

| Mean | 808 | 2035 |

| Range (n) | 655–975 (6) | 1546–2682 (6) |

| Carriers | ||

| Mother (N46S) | 495 (475–515) (61%) | 1201 (1128–1274) (59%) |

| Father (L266R) | 337 (314–361) (42%) | 834 (807–861) (41%) |

| Brother (N46S) | 361 (344–378) (45%) | 895 (864–926) (44%) |

| Mother (c.763_766dupGATT) | 355 (336–374) (44%) | 855 (817–893) (42%) |

Specific activities: carriers

The DGUOK activity was also determined for family members of patient 1. The activity levels of the mother, the father and the brother of patient 1 were all below the low end of the control range (61, 42 and 45% of the mean control value for dG, and 59, 41 and 44% of the mean control value for dA respectively). Similarly, the activity levels of the mother of patient 3 were 44 and 42% of the mean control values for dG and dA respectively (Table 1).

Kinetic properties

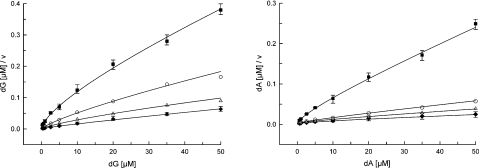

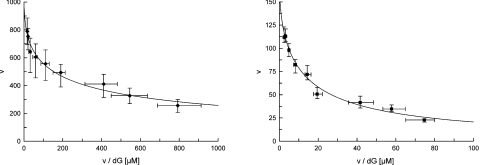

In control fibroblasts, the kinetic relationship between velocity and substrate concentration regarding the two deoxynucleoside substrates, dG and dA, was investigated and results were plotted according to the Hanes equation (s/v versus s), as well as the Eadie–Hofstee (v versus v/s) and Hill (log v/V–v versus log s) methods. Apparent Km (Km, app) and Vmax values were calculated with the Hanes equation (Figure 1). The phosphorylation of both dG and dA did not follow Michaelis–Menten kinetics but showed apparent negative co-operativity as indicated by non-linear Eadie–Hofstee plots (Figure 2) and the Hill constants n<1 (n=0.53 and 0.75 for dG and dA respectively) (Table 2). An apparent negative co-operativity was also found in mitochondria from two control livers (Hill constant mean: 0.52 and 0.70 for dG and dA respectively).

Figure 1. Kinetics of the purine deoxyribonucleoside phosphorylation by DGUOK in mitochondria from fibroblasts.

Hanes–Woolf plots of [dG]/v versus [dG] (left panel) and [dA]/v versus [dA] (right panel) for patient 1 (■), his parents [father (○) and mother (△)] and controls (◆). v, Reaction velocity. Samples containing 5 μg of mitochondrial protein were assayed under standard conditions (see the Subjects and methods section). The concentrations of dG and dA were varied from 0.3 to 50 μM and from 0.6 to 50 μM respectively, with ATP/MgCl2 fixed at 5 mM/6 mM. Velocities were expressed as picomoles of dG or dA phosphorylated per hour per milligram of protein. For wild-type DGUOK, the kinetic data are the means for three control lines within the age range of patients. For N46S/L266R mutant DGUOK (patient 1), the values are from three independent assays.

Figure 2. Negative co-operativity for the dG phosphorylation by DGUOK in mitochondria from fibroblasts.

Eadie–Hofstee plots of v versus v/[dG] with dG as the phosphate acceptor for the controls (◆) (left panel) and patient 1 (■) (right panel). v, Reaction velocity. Samples containing 5 μg of mitochondrial protein were assayed under standard conditions (see the Subjects and methods section). The concentrations of dG were varied from 0.3 to 50 μM with ATP/MgCl2 fixed at 5 mM/6 mM. Velocities were expressed as picomoles of dG phosphorylated per hour per milligram of protein. For wild-type DGUOK, the kinetic data are the means for three control lines within the age range of patients. For N46S/L266R mutant DGUOK (patient 1), the values are from three independent assays.

Table 2. Kinetic parameters of human wild-type and mutant DGUOK enzymes with the phosphate acceptors.

Samples containing 5 μg of mitochondrial protein were assayed under standard conditions (see the Subjects and methods section). The phosphate acceptor concentrations were varied from 0.3 to 50 μM and from 0.6 to 50 μM for dG and dA respectively. The ATP/MgCl2 concentration was fixed at 5 mM/6 mM. The three controls were within the age range of patients. For the patients, the values are from three different experiments. The apparent Km and Vmax values were calculated using the Hanes equation (s/v versus s). Km is given in μM and Vmax is given in picomoles of dG or dA phosphorylated per hour per milligram of protein. Also shown is the percentage of the mean control value.

| dG | dA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Km,app | Vmax/Km,app | Hill constant | Km,app | Vmax/Km,app | Hill constant | |

| Controls (n=3) | ||||||

| Mean | 1.8 | 437 | 0.53 | 6.8 | 337 | 0.75 |

| Range | (1.5–2.6) | (383–585) | (0.45–0.65) | (5.3–7.6) | (296–443) | (0.70–0.80) |

| Carriers | ||||||

| Mother (N46S) | 2.8 | 181 (41%) | 0.46 | 5.3 | 262 (78%) | 0.79 |

| Father (L266R) | 2.3 | 140 (32%) | 0.50 | 3.5 | 252 (75%) | 0.81 |

| Brother (N46S) | 1.9 | 204 (47%) | 0.59 | 4.1 | 233 (69%) | 0.74 |

| Mother (c.763_766dupGATT) | 1.6 | 222 (51%) | 0.59 | 4.8 | 184 (55%) | 0.75 |

| Patients | ||||||

| Patient 1 (N46S, L266R) | 3.4 | 39 (9%) | 0.61 | 2.6 | 83 (25%) | 0.68 |

| Patient 2 (c.142+1G>A, c.591G>A) | No kinetics | No kinetics | ||||

| Patient 3 (c.763_766dupGATT) | No kinetics | No kinetics | ||||

For patients 2 and 3, the fibroblast and liver samples showed no kinetic behaviours compared with the controls and no kinetic properties could be characterized. For the N46S/L266R mutant enzymes of patient 1, the Km,app values for both dG and dA were approx. 3 μM and in the same range as that of the controls (1.8 and 6.8 μM for dG and dA respectively) (Table 2). The mutant enzymes had 9% of the Vmax/Km, app value with dG and 25% with dA as compared with the wild-type DGUOK enzyme. Negative co-operativity was also found (Hill constants: 0.61 and 0.68 for dG and dA respectively). Negative co-operativity was furthermore observed for both dG and dA in all carriers (Table 2). The Vmax/Km,app values with dG or dA as the phosphate acceptors ranged from 32 to 51% with dG and from 55 to 78% of the mean control value with dA respectively.

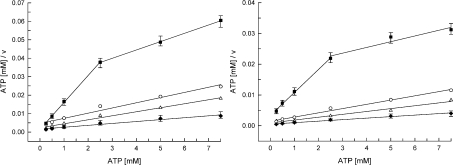

The mutant enzymes were also characterized with regard to the phosphate donor properties with ATP. The Km, app values for wild-type DGUOK were 1.5 and 0.95 mM when dG and dA were the phosphate acceptors respectively (Table 3). The values of Hill constants (0.80 and 0.77 with ATP/dG and ATP/dA respectively) indicate that wild-type DGUOK has a negative co-operativity with ATP as the substrate. Negative co-operativity was also shown for the carriers. In contrast, the N46S/L266R mutant enzymes (patient 1) exhibited two phases of the velocity curve when ATP/v values were plotted versus ATP/dA or ATP/dG concentrations compared with the controls or the carriers (Figure 3). A transition in the velocity curve is clearly observed at 2.5 mM ATP. Consequently, kinetic data showed bimodal plots using the Hanes equation. Apparent Km and Vmax values were calculated separately for the two distinct regions. At low concentrations, ATP appears to be a more efficient phosphate donor for dG and dA, having higher efficiencies (Vmax/Km,app) and lower Km, app values as compared with the situation at concentrations above the transition point (Table 3).

Table 3. Kinetic parameters of human wild-type and N46S/L266R DGUOK enzymes with the phosphate donor.

The values are determined with fixed concentrations of dG or dA (20 μM) and concentrations of ATP varied from 0.25 to 7.5 mM. The three controls were within the age range of patients. Conditions and analysis of data were as described in Table 2. Km is given in mM and Vmax is given in picomoles of dG or dA phosphorylated per hour per milligram of protein; Km1, Vmax1, n°1: (first value of Vmax/Km,app for the patient) data below 2.5 mM ATP; Km2, Vmax2, n°2: (second value of Vmax/Km,app for the patient) data above 2.5 mM ATP. Also shown is the percentage of the mean control value.

| ATP/dG | ATP/dA | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Km,app | Vmax | Vmax/Km,app | Hill constant | Km,app | Vmax | Vmax/Km,app | Hill constant | |

| Controls (n=3) | ||||||||

| Mean | 1.5 | 1030 | 687 | 0.80 | 0.95 | 2066 | 2175 | 0.77 |

| Range | (1.4–1.7) | (706–1196) | (474–848) | (0.70–0.89) | (0.9–1.1) | (1697–2527) | (1786–2808) | (0.69–0.83) |

| Carriers | ||||||||

| Mother (N46S) | 1.1 | 474 | 431 (63%) | 0.83 | 0.95 | 1072 | 1128 (52%) | 0.67 |

| Father (L266R) | 1.3 | 348 | 268 (39%) | 0.83 | 1.0 | 696 | 696 (32%) | 0.88 |

| Brother (N46S) | 1.25 | 410 | 328 (48%) | 0.81 | 1.1 | 879 | 799 (37%) | 0.68 |

| Mother (c.763_766dupGATT) | 1.7 | 483 | 284 (41%) | 0.78 | 0.8 | 826 | 1032 (47%) | 0.86 |

| Patient | ||||||||

| Patient 1 (N46S, L266R) | Km1=0.45 | Vmax1=67 | n°1=149 (22%) | − | Km1=0.45 | Vmax1=134 | n°1=298 (14%) | − |

| Km2=4.5 | Vmax2=193 | n°2=43 (6%) | − | Km2=9.4 | Vmax2=489 | n°2=52 (2.4%) | − | |

Figure 3. Kinetics of the phosphate transfer by DGUOK in mitochondria from fibroblasts.

Hanes–Woolf plots of [ATP]/v versus [ATP] with dG as the phosphate acceptor (left panel) and [ATP]/v versus [ATP] with dA as the phosphate acceptor (right panel) for patient 1 (■), his parents [father (○) and mother (△)] and controls (◆). v, Reaction velocity. For controls and carriers, the slope of the plot gives 1/Vmax, app. Samples containing 5 μg of mitochondrial protein were assayed under standard conditions (see the Subjects and methods section). The concentrations of ATP were varied from 0.25 to 7.5 mM, with dG or dA fixed at 20 μM. Velocities were expressed as in Figure 1. For wild-type DGUOK, the kinetic data are the means for three control lines within the age range of patients. For N46S/L266R mutant DGUOK (patient 1), the values are from three independent assays.

DISCUSSION

We identified the nuclear gene involved in the liver-restricted MDS of patient 1, a 10-year-old who presented with a favourable course of the disease. The patient had two missense mutations (N46S/L266R) in his DGUOK gene. DGUOK mutations were initially reported in the hepatocerebral form of mtDNA depletion [5,10] but can cause also isolated liver disease [3]. To date, the DGUOK mutations reported in patients with liver or hepatocerebral MDS result either in a premature stop codon and truncation of the DGUOK protein [3–5,10,17] or in amino acid substitutions [3,4]. In patient 2 with the hepatocerebral form of MDS, we identified the first splice mutations in DGUOK leading to an absence of correctly processed DGUOK transcript. For patient 3, who died at 2 months of age, the isolated hepatic form was related to a 4 bp duplication in exon 6 resulting in a premature stop codon at amino acid 255 [3]. A recombinant enzyme, generated with the same C-terminal 22-amino-acid truncation, was inactive and deletions of the C-terminal 11 or 18 amino acids resulted also in inactive enzymes, suggesting that the C-terminal α-9 α-helical domain of DGUOK plays a critical role in catalysis [19].

In contrast, patient 1 with the reversal form of MDS had two missense mutations, one of them (N46S) yet unreported. Residue Asn46 is one of the four highly conserved residues (positions 44–47) in the P-loop of the protein family of deoxynucleoside kinases. The P-loop is essential for the binding of the phosphates of ATP by the residues Ala48, Lys51 and Ser52. Interactions of the triphosphate part of ATP involve also the LID region (Arg206 and Arg208) and the Arg142 residue present in the loop preceding helix α5. Using Swiss-Pdb Viewer (http://www.expasy.ch/spdbv) [29] to visualize the three-dimensional structures of mutant enzymes compared with the wild-type model [11], it appears that the N46S mutation induces a drastic change in the close interactions with amino acid 46. In the Ser46 protein, the interactions with five residues disappear, four of them (the conserved Tyr218, Glu220, Gln221 and Gly224) belonging to the helix α8 and one residue (the conserved Pro196) belonging to the helix α7 (Supplementary Figure 3A at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/402/bj4020377add.htm). This predicted change probably impairs the phosphate bonds between ATP and both the P-loop and the LID region and, consequently, causes destabilization of the DGUOK–ATP complex essential for an optimum catalytic transfer of a phosphate group to dG or dA. The other mutation, L266R, was reported in another patient recently [4]. The mutation affects a residue in the C-terminal α-9 α-helical domain, which is not conserved throughout the family of deoxynucleoside kinases [11]. Substitution of the aliphatic residue leucine for the basic residue arginine introduces abnormal and tight interactions between the C-terminal α-9 domain and both the β4 and β5 helices via the two conserved residues Tyr191 and Leu192, and the non-conserved residues Gln193, Val249 and Leu250 (Supplementary Figure 3B). Such interactions are likely to alter not only the proper folding of the C-terminal domain but also the conformation of domains close to the C-terminus.

In order to evaluate the consequences of these two missense mutations on the catalytic activity, an enzymatic assay was developed for mitochondria-enriched preparations from cultured fibroblasts. This assay was optimized for a detailed characterization of the kinetic parameters of the enzyme: the Km, app values for the phosphate acceptors (dG and dA) and for the phosphate donor (ATP), the efficiency (Vmax/Km, app) and the Hill constants. In normal mitochondria, the reaction kinetics of DGUOK do not follow the Michaelis–Menten model but show apparent negative co-operativity with the phosphate acceptors (dG or dA) and donor (ATP) as indicated by non-linear Eadie–Hofstee plots and Hill constants below unity. Such a mechanism was previously reported for the phosphorylation of dC and dT (deoxythymidine) by human dCK [30] and TK2 [31] respectively. For purified DGUOK from beef liver mitochondria, a random bi-kinetic mechanism has been reported with the formation of a dead-end complex but without clear information about co-operativity [15]. In organello, negative co-operativity would tend to limit the initial velocity of the dimeric enzyme with increasing substrate concentrations and would contribute together with the feedback inhibition of the end-products [15] to regulate the purine dNTP pool. In mitochondria from control fibroblasts, the Km, app values with dG and dA were 1.8 and 6.8 μM respectively, but the Vmax was 3-fold higher with dA reducing the efficiency of dA phosphorylation by only 23%. The Km, app value for dG was in the same range as the values reported for the purified bovine enzyme (4.7–7.6 μM) [12,14] and human recombinant enzyme (4 μM) [16,19]. In contrast, the Km, app value for dA was lower compared with those reported previously (60 and 467 μM for purified bovine and human recombinant enzyme respectively). In our mitochondria-enriched preparations from fibroblasts, the product of dA phosphorylation is in part dIMP (deoxyinosine monophosphate), the deamination occurring at the nucleoside level by a contaminating adenosine deaminase activity (results not shown). As DGUOK phosphorylates also dI (deoxyinosine) with an efficiency higher than for dG or dA [12,16], the Km value and efficiency for dA we measured in fibroblast mitochondria may reflect in part the phosphorylation rate of the enzyme for dI. This may explain why the efficiency for dG was not severalfold higher than for dA as described for the purified bovine and human recombinant enzyme (12-fold) [12,16].

The N46S/L266R enzymes showed a decreased catalytic rate with dG and dA (14 and 10% of the mean control activity with dG and dA respectively) but results indicated no alteration of substrate binding capacity as revealed by the Km, app values and no change in apparent negative co-operativity with dG and dA as substrates. Indeed, the predicted N46S/L266R DGUOK three-dimensional structure models do not affect the main residues involved in the active site, especially Arg118 and Asp147 [11]. We cannot conclude that catalytic efficiency (Vmax/Km, app) for dG or dA phosphorylation is reduced as Vmax is also dependent on amounts of the mutant DGUOK protein. In contrast, the velocity was reduced by more than 97% in the patients 2 and 3 with the splice mutations and the GATT duplication respectively, and kinetic behaviours were absent. Phosphorylation of dG and dA over the long incubation time by even a low level of contaminating cytosolic dCK may explain these residual activities despite the presence of excess dC (2 mM), which is not only the more efficient substrate for dCK but also a strong inhibitor of the purine phosphorylation carried out by dCK [13,32].

When ATP was used as a limiting phosphate donor, patient 1 mutant enzymes showed abnormal kinetics. The two distinct regions of the velocity curve separated by an obvious transition indicate the presence of two different kinetic behaviours, one for the lower ATP concentrations and the other for the higher ones. At the low concentration range, a severely decreased catalytic rate (Vmax1 reduced by more than 90%) was observed rather than an alteration of substrate binding capacity as revealed by the Km, app values. With increasing ATP concentrations, the mutant undergoes an increase in apparent. Km for ATP (3–10-fold the control values with dG and dA respectively), with the transition to higher Km, app being accompanied by a shift to greater maximum velocity (Vmax2 only 5-fold reduced compared with the control Vmax). Biphasic velocity curves have been described in preparations containing two enzymes (or two forms of the same enzyme) catalysing the same reaction [28]. We have to keep in mind that three different mutant dimers of the enzyme theoretically co-exist (N46S/N46S, L266R/L266R and N46S/L266R) in mitochondria of patient 1, if some of them are not degraded. In such a system, the observed velocity would be the sum of the velocities contributed by each mutant dimer. In addition to the conformational change of the P-loop predicted in the mutant Ser46, the stability of the P-loop three-dimensional structure may be compromised by the unusual interactions of the C-terminal domain and the β4 and β5 helices predicted in the mutant Arg266. As a result, the two mutations may both contribute to the impairment of the binding mode of ATP at the phosphate donor site, decreasing both the intrinsic affinity of the phosphate donor site and the rate of the phosphate transfer.

We demonstrated a low DGUOK enzyme activity in the fibroblasts of a patient who displayed a spontaneous improvement of his liver MDS. The mtDNA content of his exponentially growing fibroblasts was only partially decreased. It is well established that during S-phase when both the cytosolic de novo synthesis of deoxynucleotides and the dCK are high, the import of purine deoxynucleotides sustains mtDNA synthesis in DGUOK-deficient cells [33]. In liver of patient 1, the DGUOK mutations caused a severe mtDNA depletion (85 and 80% at 12 and 21 months of age respectively) responsible for an extensive liver fibrosis [2]. Although we assume that mutant DGUOK showed also residual activity in liver, this was apparently not enough to supply sufficient mitochondrial purine deoxynucleotides for normal mtDNA replication. Unfortunately, no liver samples were available from the patient to assess liver DGUOK activity directly. On the other hand, the absence of brain dysfunction in patient 1 argues for a residual DGUOK activity compatible with a normal neurological development. In the neonatal period, liver and brain are tissues relying mostly on oxidative phosphorylation for ATP production. mtDNA replication is highly dependent on DGUOK without the compensatory effect of both cytosolic de novo dNTP synthesis, which is limited in post-mitotic tissues, and dCK activity, which is known to be very low in these tissues [34].

We hypothesize that the residual DGUOK activity accounts for the highly unusual phenotypic reversal. At 32 months of age, the patient displayed a spontaneous gradual improvement of his liver function with no extrahepatic manifestations. It appears that after the neonatal period, the mtDNA needs were lowered and the DGUOK activity became less critical. Even a low DGUOK activity may prevent further disease development and allow regeneration of the damaged liver. Moreover, the special regimen since 3 months of age, including daily fractional meals and enteral nutrition during the night supplemented with medium chain triacylglycerols, was probably effective to limit the liver energy requirements. In the literature, only one heterozygous patient (R142K/E227K) had a documented residual DGUOK activity in liver (27% as compared with control individuals) [3]. As he underwent liver transplantation at the age of 17 months, the natural course of his liver MDS is unknown.

Alternatively, the reversion of the phenotype may be explained by a somatic nuclear mosaicism confined to liver. Reversion by mosaicism may occur, early in development, in one somatic cell, either from a de novo mutation that could rescue the mutant allele or by creating a normal allele from a mutant by gene conversion [35]. In these cases, the DGUOK activity would be higher in liver than in fibroblasts. To test this hypothesis, a liver biopsy is needed. Such a mosaicism could promote a functioning cell pool and may prevent liver failure mainly from accelerated cell regeneration. Whatever the molecular mechanism of a hypothetic reversion event, reversion clusters with normal hepatocytes on light microscopy and fully restored function co-exist in the patient's liver with some areas of residual fibrosis [1].

The optimized protocol of DGUOK activity measurement we developed for mitochondria from fibroblasts (and liver) allowed us to get a deeper understanding of the kinetic properties of the DGUOK enzyme and to evaluate the kinetic behaviour of mutant enzymes in organello. Experimental kinetic results obtained in organello reflect the enzymatic function of DGUOK, which depends on specific conditions of processing, folding and monomeric interactions. In the N46S/L266R mutant, even though the kinetic properties of each mutant enzyme cannot be resolved by this experimental approach, the characterization of a residual DGUOK activity in organello provides a general view of the mechanism leading to a reduced purine deoxynucleotide pool through the salvage pathway.

Online data

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Professor Guibaud, and Dr Till and Dr Guffon for sending us the patient 2 and 3 samples respectively. The paper is dedicated to Mrs J. Mousson.

References

- 1.Ducluzeau P.-H., Lachaux A., Bouvier R., Duborjal H., Stepien G., Bozon D., Mousson de Camaret B. Progressive reversion of clinical and molecular phenotype in a child with liver mitochondrial DNA depletion. J. Hepatol. 2002;36:698–703. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ducluzeau P.-H., Lachaux A., Bouvier R., Streichenberger N., Stepien G., Mousson B. Depletion of mitochondrial DNA associated with infantile cholestasis and progressive liver fibrosis. J. Hepatol. 1999;30:149–155. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(99)80019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salviati L., Sacconi S., Mancuso M., Otaegui D., Camaño P., Marina A., Rabinowitz S., Shiffman R., Thompson K., Wilson C. M., et al. Mitochondrial DNA depletion and dGK gene mutations. Ann. Neurol. 2002;52:311–317. doi: 10.1002/ana.10284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Slama A., Giurgea I., Debrey D., Bridoux D., de Lonlay P., Levy P., Chretien D., Brivet M., Legrand A., Rustin P., et al. Deoxyguanosine kinase mutations and combined deficiencies of the mitochondrial respiratory chain in patients with hepatic involvement. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2005;86:462–465. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mandel H., Szargel R., Labay V., Elpeleg O., Saada A., Shalata A., Anbinder Y., Berkowitz D., Hartman C., Barak M., et al. The deoxyguanosine kinase gene is mutated in individuals with depleted hepatocerebral mitochondrial DNA. Nat. Genet. 2001;29:337–341. doi: 10.1038/ng746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saada A., Shaag A., Mandel H., Nevo Y., Eriksson S., Elpeleg O. Mutant mitochondrial thymidine kinase in mitochondrial DNA depletion myopathy. Nat. Genet. 2001;29:342–344. doi: 10.1038/ng751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elpeleg O., Miller C., Hershkovitz E., Bitner-Glindzicz M., Bondi-Rubinstein G., Rahman S., Pagnamenta A., Eshhar S., Saada A. Deficiency of the ADP-forming succinyl-CoA synthase activity is associated with encephalomyopathy and mitochondrial DNA depletion. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2005;76:1081–1086. doi: 10.1086/430843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naviaux R. K., Nguyen K. V. POLG mutations associated with Alpers' syndrome and mitochondrial DNA depletion. Ann. Neurol. 2004;55:706–712. doi: 10.1002/ana.20079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spinazzola A., Viscomi C., Fernandez-Vizarra E., Carrara F., D'Adamo P., Calvo S., Marsano R. M., Donnini C., Weiher H., Strisciuglio P., et al. MPV17 encodes an inner mitochondrial membrane protein and is mutated in infantile hepatic mitochondrial DNA depletion. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:570–575. doi: 10.1038/ng1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taanman J.-W., Chatib I., Muntau A. C., Jaksch M., Cohen N., Mandel H. A novel mutation in the deoxyguanosine kinase gene causing depletion of mitochondrial DNA. Ann. Neurol. 2002;52:237–239. doi: 10.1002/ana.10247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johansson K., Ramaswamy S., Ljungcrantz C., Knecht W., Piškur J., Munch-Petersen B., Eriksson S., Eklund H. Structural basis for substrate specificities of cellular deoxyribonucleoside kinases. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2001;8:616–620. doi: 10.1038/89661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang L., Karlsson A., Arner E. S. J., Eriksson S. Substrate specifity of mitochondrial 2′-deoxyguanosine kinase. Efficient phosphorylation of 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:22847–22852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arnér E. S. J., Eriksson S. Mammalian deoxyribonucleoside kinases. Pharm. Ther. 1995;67:155–186. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(95)00015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park I., Ives D. H. Properties of a highly purified mitochondrial deoxyguanosine kinase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1988;266:51–60. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(88)90235-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park I., Ives D. H. Kinetic mechanism and end-product regulation of deoxyguanosine kinase from beef liver mitochondria. J. Biochem. 1995;117:1058–1061. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herrström Sjöberg A., Wang L., Eriksson S. Substrate specificity of human recombinant mitochondrial deoxyguanosine kinase with cytostatic and antiviral purine and pyrimine analogs. Mol. Pharmacol. 1998;53:270–273. doi: 10.1124/mol.53.2.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Labarthe F., Dobbelaere D., Devisme L., de Muret A., Jardel C., Taanman J.-W., Gottrand F., Lombes A. Clinical, biochemical and morphological features of hepatocerebral syndrome with mitochondrial DNA depletion due to deoxyguanosine kinase deficiency. J. Hepatol. 2005;43:333–341. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tadiboyina V. T., Rupar A., Atkison P., Feigenbaum A., Kronick J., Wang J., Hegele R. A. Novel mutation in DGUOK in hepatocerebral mitochondrial DNA depletion syndrome associated with cystathioninuria. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2005;135:289–291. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang L., Eriksson S. Mitochondrial deoxyguanosine kinase mutations and mitochondrial DNA depletion syndrome. FEBS Lett. 2003;554:319–322. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01181-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Procaccio V., Mousson B., Beugnot R., Duborjal H., Feillet F., Putet G., Pignot-Paintrand I., Lombes A., De Coo R., Smeets H., et al. Nuclear DNA origin of mitochondrial complex I deficiency in fatal infantile lactic acidosis evidenced by transnuclear complementation of cultured fibroblasts. J. Clin. Invest. 1999;104:83–92. doi: 10.1172/JCI6184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bourges I., Ramus C., Mousson de Camaret B., Beugnot R., Remacle C., Cardol P., Hofhaus G., Issartel J.-P. Structural organization of mitochondrial human complex I: role of the ND4 and ND5 mitochondria-encoded subunits and interaction with the prohibitin. Biochem. J. 2004;383:491–499. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rustin P., Chretien D., Bourgeron T., Gérard B., Rötig A., Saudubray J.-M., Munnich A. Biochemical and molecular investigations in respiratory chain deficiencies. Clin. Chim. Acta. 1994;228:35–51. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(94)90055-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ives D. H., Wang S. M. Deoxycytidine kinase from calf thymus. Methods Enzymol. 1978;51:337–345. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(78)51045-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chabi B., Mousson de Camaret B., Duborjal H., Issartel J.-P., Stepien G. Quantification of mitochondrial DNA deletion, depletion and overreplication: application to diagnosis. Clin. Chem. 2003;49:1309–1317. doi: 10.1373/49.8.1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taanman J.-W., Bodnar A. G., Cooper J. M., Morris A. A. M., Clayton P. T., Leonard J. V., Schapira A. H. V. Molecular mechanisms in mitochondrial DNA depletion syndrome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1997;6:935–942. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.6.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johansson M., Karlsson A. Cloning and expression of human deoxyguanosine kinase cDNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996;93:7258–7262. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.14.7258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kozak M. Recognition of AUG and alternative initiator codons is augmented by G in position +4 but is not generally affected by the nucleotides in positions +5 and +6. EMBO J. 1997;16:2482–2492. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.9.2482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Segel I. H. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1975. Enzyme Kinetics, Behavior and Analysis of Rapid Equilibrium and Steady-state Enzyme Systems. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guex N., Peitsch M. C. Swiss-Model and the Swiss-Pdb Viewer: an environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis. 1997;18:2714–2723. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150181505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ives D. H., Durham J. P. Deoxycytidine kinase. III. Kinetics and allosteric regulation of the calf thymus enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 1970;245:2285–2294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Munch-Petersen B., Cloos L., Tyrsted G., Eriksson S. Diverging substrate specificity of pure human thymidine kinases 1 and 2 against antiviral dideoxynucleosides. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:9032–9038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bohman C., Eriksson S. Deoxycytidine kinase from human leukemic spleen: preparation and characterization of the homogeneous enzyme. Biochemistry. 1988;27:4258–4265. doi: 10.1021/bi00412a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taanman J.-W., Muddle J. R., Muntau A. C. Mitochondrial DNA depletion can be prevented by dGMP and dAMP supplementation in a resting culture of deoxyguanosine kinase-deficient fibroblasts. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2003;12:1839–1845. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eriksson S., Munch-Petersen B., Johansson K., Eklund H. Structure and function of cellular deoxyribonucleoside kinases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2002;59:1327–1346. doi: 10.1007/s00018-002-8511-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pasmooij A. M. G., Pas H. H., Deviaene F. C. L., Nijenhuis M., Jonkman M. F. Multiple correcting COL17A1 mutations in patients with revertant mosaicism of epidermolysis bullosa. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2005;77:727–740. doi: 10.1086/497344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.