Abstract

An investigation in a referral pediatric hospital has indicated that during a recent dengue outbreak in Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India, dengue in infancy constituted 20% of total dengue virus infections with low mortality rates in this hospital. In developing countries, strengthening of dengue management capabilities at hospitals can prevent dengue-related deaths in infants.

Dengue, the most significant mosquito-borne viral disease, affects humans of all age groups worldwide (TDR News, vol. 66, p. 10, 2001). In some parts of the world, it is mainly a pediatric public health problem. In Thailand, dengue in infancy (≤2 years of age) is a serious medical concern, constituting 7.7 and 2.9% (rates observed in two different hospitals) of dengue virus infections (5, 6). However, the case fatality rate is low due to early diagnosis and prompt treatment (6). Dengue in infancy has also been reported from India and Sri Lanka (1, 3).

In India, dengue epidemics have been reported in many parts of the country. The incidence was reported to be high among children ≥8 years of age, and some infants presented with severe forms of dengue (2). Due to lack of awareness of dengue in general, the present surveillance system in India is unlikely to generate reliable dengue epidemiological database information, which is essential for better clinical assessment and management.

Between September 2001 and January 2002, an epidemic of dengue occurred in Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India. Nearly 800 cases were reported to the health system. A total of 192 children (<15 years of age) with clinical dengue attending Kanchi Kamakoti Childs Trust Hospital (KKCTH) were investigated for confirmation of dengue. KKCTH is one of the major referral pediatric hospitals in Tamil Nadu. A descriptive study was undertaken in collaboration with the pediatricians of this hospital to evaluate the burden, severity, and outcome of dengue virus infections in 143 hospitalized children (0 to 15 years of age) for whom complete clinical data during hospitalization were available. Here, we report mainly the results obtained from the analysis of dengue virus infections in 34 infants (≤1 year of age).

Hemoglobin, hematocrit, platelet, and leukocyte counts were determined in most of the cases. Skiagram chest and liver function tests were done for some patients. The serum samples collected from these infants were analyzed for dengue virus-specific immunoglobulin M (IgM) and IgG antibodies by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using two commercial kits (PanBio, Brisbane, Australia, and Omega, Alloa, Scotland) alternatively, depending upon availability. Dengue virus infections were confirmed by clinical and laboratory criteria. Facilities were not available at this hospital to isolate the virus from acute-phase serum samples.

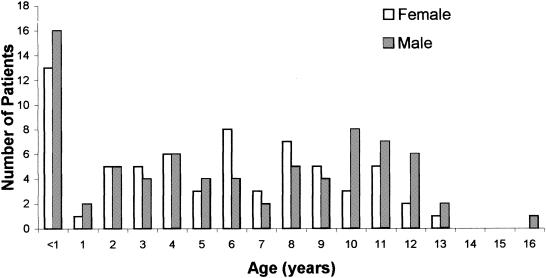

Dengue virus infection was diagnosed in 74.5% (143 of 192) of cases. Figure 1 shows the age, sex, and frequency distribution of cases of children with dengue virus infection. In this study, nearly 20% (29 of 143) of these cases were infections of infants <1 year of age. Ages ranged from 1 to 11 months; the mean age was 7 months. There was no report of mortality due to dengue in this hospital during the study period. Clinical features and laboratory findings determined for the study patients (infants [<1 year of age] and older children [>1 to 15 years of age]) are shown in Table 1. Almost all of the children had fever at the time of admission. While infants had high-grade fevers, most of the older children had intermittent fevers. Fever, hepatomegaly, and rashes were seen in 100, 93.1, and 55.2% of the infants, respectively. Edema of the lower extremities, retroorbital puffiness, and vomiting and convulsions were seen in 17.2, 27.6, and 24.1% of the infants, respectively (Table 1). The laboratory findings are given in Table 1. The mean hematocrit values were 31.1 and 36.03% for infants and older children. Nearly 50% of the study subjects had hematocrit values ranging from 30 to 40% (Table 1). In the present study, only 15% of infants and 21% of the 1- to 15-year-old group had hematocrit values of >40% and there were no significant differences between these two groups. However, hematocrit values of less than 30% were seen at a higher frequency among infants (infants = 35%; older children = 19.5%) and the difference was significant (Table 1). Although thrombocytopenia (average platelet count, <100,000/mm3) was demonstrated for the majority of the patients irrespective of age, the mean platelet count for the infants (56,900/mm3) was significantly less than that for the older children (Table 1). Nearly 51.1% of the infants had platelet counts of less than 80,000/mm3.

FIG. 1.

Age- and sex-specific distribution of dengue virus-infected children in a hospital-registered sample.

TABLE 1.

Clinical features and laboratory findings for dengue virus-infected infants and older children in the 2001 to 2002 dengue epidemic in Chennai, India

| Feature or finding | No. of casesa

|

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infants | Children | ||

| Fever | 100 | 100 | NSb |

| Vomiting | 24 | 43 | 0.004 |

| Rash | 55.2 | 42.1 | 0.065 |

| Petechiae | 0 | 17.5 | 0.00003 |

| Hematemesis | 0 | 4.4 | 0.04 |

| Maleana | 3.4 | 2.6 | NS |

| Hematuria | 3.4 | 3.5 | NS |

| Epistaxis | 0 | 2.6 | NS |

| Edema | 17.2 | 11.4 | NS |

| Drowsiness | 20.7 | 12.3 | NS |

| Convulsions | 10.3 | 3.5 | NS |

| Restlessness | 3.4 | 10.5 | 0.02 |

| Retroorbital puffiness | 27.6 | 15.8 | 0.04 |

| Hepatomegaly | 93.1 | 83.3 | 0.029 |

| Hematocrit value ofc: | |||

| >40% | 15 | 21.7 | NS |

| 30-40% | 50 | 55 | NS |

| ≤30% | 35 | 19.5 | 0.01 |

| Platelet count | 56,900 | 84,400 | 0.0001 |

Values are percentages, except for mean platelet counts, which are, not numbers of cases, but numbers of platelets per millimeter cubed. Study patients were divided into two groups according to age: infants (n = 29; age, <1 year) and children (n = 114; age range, >1 to 15 years).

NS, not statistically significant.

Laboratory findings.

According to World Health Organization clinical criteria (7), dengue fever (DF), dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF), and dengue shock syndrome (DSS) were diagnosed in 82.8% (24 of 29), 3.4% (1 of 29), and 13.8% (4 of 29) of serologically confirmed cases of dengue in infants, respectively (Table 2). Both of the sexes were equally affected in the case of DF. All of the four infants with DSS were males, the youngest being 30 days old. While dengue-specific IgM responses were predominant in most (23 of 24) of the DF cases, the five infants with severe forms of dengue disease elicited IgG responses with or without IgM responses (Table 2), suggesting that the DF and DHF-DSS cases were due to primary and secondary dengue virus infections, respectively. The IgM antibody responses against dengue virus serotype 4 antigens seen with most of the serum samples indicated that dengue virus serotype 4 was the infecting virus in these patients.

TABLE 2.

DF, DHF, and DSS among infants and anti-dengue virus antibody responses

| Disease | Total no. (%) of reactive cases | Total no. of cases reactive with:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgM | IgG | IgM and IgG | ||

| DF | 24 (82.8) | 23 | 1 | |

| DHF | 1 (3.4) | 1 | ||

| DSS | 4 (13.8) | 2 | 2 | |

The incidence of dengue virus infections in infancy amounted to 20% of dengue virus infections in children attending a pediatric referral hospital during an outbreak of dengue in Chennai, India. In general, the clinical presentations and laboratory findings appeared to be the same in both of the groups, as observed by other researchers (6). However, in our study, certain features like convulsions, drowsiness, retro-orbital puffiness, and rash were observed frequently in infants; vomiting, restlessness, and abdominal pain were predominant in older children. The occurrence of convulsions in infants seen here may have been due to fever since these infants had high-grade fever, which may also have been responsible for the drowsiness. An incidence of convulsions in infants with dengue has been reported by others (5). Considering the nutritional status and possibilities of coinfections in the children, it may be difficult to elucidate signs and symptoms specific to dengue virus infections pertaining to childhood age groups.

Though thrombocytopenia was more pronounced in infants than in the older children, complications due to bleeding were less pronounced in infants. Similar observations were reported elsewhere (5). This may have been due to the early hospitalization and prompt treatment provided by KKCTH before the onset of complications. The mean white blood cell (WBC) counts were 5,500 cells/mm3 for infants and 6,750 cells/mm3 for older children. We were unable to demonstrate hemoconcentration values corresponding to dengue severity in the absence of preillness hematocrit values. Generation and standardization of hematocrit and WBC count values from normal children living in different parts of India are necessary, since anemia is highly prevalent throughout the country. Until such data are available, application of international standard hematocrit and WBC count values for diagnosis of dengue may not be of relevance in this part of the world.

In general, dengue in infancy is due to primary infections, which are less likely to develop into severe forms than secondary infections. However, investigations from India indicate that severe dengue virus infections do occur in infancy (1). It was reported of the Delhi epidemic that 9% of the infected infants presented clinical features of DHF, the youngest of the infants being 3 months of age (1), and that none had DSS. Studies from Thailand have also shown a lower incidence of DSS in infancy (5). In our investigation, the proportion of infants with DSS was higher than that of children with DHF. It is postulated that severe forms of dengue are attributable to the circulation of antibodies to two or more dengue virus serotypes. The severe manifestations seen in infants in this analysis suggest that the infants might have acquired antibodies to two dengue virus serotypes by (i) passive transfer of maternal antibodies and (ii) sequential exposure to primary infections at an early age. Establishment of evidence for sequential exposure of these infants to two serotypes of dengue virus would confirm this explanation. However, one cannot ignore the role of viral virulence in the disease mechanism.

The Chennai dengue epidemic was characterized as a DF epidemic with fewer complications. As a result of the early preparedness of the hospital for dengue management, there was no record of mortality due to dengue (even for infants) in the hospital during the study period. The Delhi epidemic demonstrated a high occurrence of DHF-DSS resulting in 6% mortality (the cases of the patients who died belonged to grade IV DHF-DSS) (1), which may have been due to delay in recognition and treatment. However, the reports from Thailand indicated that dengue virus infections during infancy were believed to have been due to primary infection (5, 6), which can be fatal, leading to 5.9% of dengue-related deaths among these infants (5) The occurrence of fatal primary dengue virus infections in adults has been recorded in Brazil (4).

We conclude from our analysis that mild to severe forms of dengue virus infections can occur in infancy in this region. Dengue virus infections should not be ruled out based only on the criterion of very young age since there are difficulties in the diagnosis of dengue virus infections in this group, whose members are very young, fragile, and sensitive and cannot express themselves. The clinical signs, symptoms, and laboratory findings observed here were similar to those of reports from other regions (1, 5, 6) and not specific to different age groups. Hematocrit and WBC count values useful for diagnosis of dengue in Indian population need to be derived and standardized.

In the dengue epidemic reported here, infants (≤1 year of age) constituted 20% of hospitalized and confirmed dengue virus infections at KKCTH, Chennai, India. A disproportionately high percentage of infants suffered in this epidemic, whose proportion of cases is higher than that in Thailand, where they have categorized children up to 2 years of age as infants (5). Dengue virus infections in infancy may pose a serious public health problem in India, considering the quantum of the vulnerable infant population, the proportion of dengue virus infections among hospitalized infants, and the wide scattering of dengue-prone areas. The mortality rate is low in the present epidemic. However, the scenario might change in impending epidemics. In view of the less-developed immune mechanisms leading to vulnerability of infants to higher mortality rates, it would be ideal to gear up pediatric hospitals for dengue management capabilities.

Acknowledgments

We thank T. Balaji of the Centre for Research in Medical Entomology, Madurai, India, and Srija of KKCTH, Chennai, India, for technical assistance. We also thank the staff and patients of KKCTH, Chennai, India, for their kind cooperation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aggarwal, A., J. Chandra, S. Aneja, A. K. Patwari, and A. K. Dutta. 1998. An epidemic of dengue hemorrhagic fever and dengue shock syndrome in children in Delhi. Indian Pediatr. 35:727-732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kabra, S. K., Y. Jain, R. M. Pandey, Madhulika, T. Singhal, P. Tripathi, S. Broor, P. Seth, and V. Seth. 1999. Dengue haemorrhagic fever in children in the 1996 Delhi epidemic. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 93:294-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lucas, G. N., and G. F. Mendis. 2001. Dengue haemorrhagic fever in infancy. Sri Lanka J. Child. Health 30:96-97. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nogueira, R. M. R., M. P. Miagostovitch, R. V. Cubha, S. M. O. Zagne, F. P. Gomes, A. F. Nicol, J. C. O. Coelho, and H. G. Schatzmayr. 1999. Fatal primary dengue infections in Brazil. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 93:418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pancharoen, C., and U. Thisyakorn. 2001. Dengue virus infection during infancy. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 95:307-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Witayathawornwong, P. 2001. Dengue hemorrhagic fever in infancy at Petchabun Hospital, Thailand. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 32:481-487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. 1998. Dengue haemorrhagic fever: diagnosis, treatment, prevention, and control, 2nd edition, p. 12-23. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.