Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the long‐term safety and efficacy of etanercept in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

Methods

549 patients entered this 5‐year, open‐label extension study and received etanercept 25 mg twice weekly. All patients showed inadequate responses to disease‐modifying antirheumatic drugs before entry into the double‐blind studies. Safety assessments were carried out at regular intervals. Primary efficacy end points were the numbers of painful and swollen joints; secondary variables included American College of Rheumatology (ACR) response rate, Disease Activity Score and acute‐phase reactants. Efficacy was analysed using the last‐observation‐carried‐forward approach.

Results

Of the 549 patients enrolled in the open‐label trial, 467 (85%), 414 (75%) and 371 (68%) completed 1, 2 and 3 years, respectively; 363 (66%) remained in the study at the time of this analysis. A total exposure of 1498 patient‐years, including the double‐blind study, was accrued. In the open‐label trial, withdrawals for efficacy‐related and safety‐related reasons were 11% and 13%, respectively. Frequent adverse events included upper respiratory infections, flu syndrome, rash and injection‐site reactions. Rates of serious infections and malignancies remained unchanged over the course of the study; there were no reports of patients with central demyelinating disease or serious blood dyscrasias. After 3 years, ACR20, ACR50 and ACR70 response rates were 78%, 51% and 27%, respectively. The Disease Activity Score score was reduced to 3.0 at 3 months and 2.6 at 3 years from 5.1. A sustained improvement was found in Health Assessment Questionnaire scores throughout the 3‐year time period.

Conclusion

After 3 years of treatment, etanercept showed sustained efficacy and a favourable safety profile.

The introduction of biological antirheumatic treatments, such as etanercept, in the late 1990s, represents a qualitative advance in the practice of rheumatology. In several well‐controlled studies, etanercept versus placebo or methotrexate markedly reduced disease activity and rate of progression of joint damage, with limited toxicity.1,2,3,4,5,6 These studies, of 24 months duration, contributed to the establishment of the efficacy and safety profile of etanercept. To more fully assess the long‐term effects of treatment, studies of longer etanercept treatment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis are necessary.

Theoretical considerations in the long‐term use of etanercept include immunosuppression and its effect on the development of infections and malignant tumours. To deal with these concerns, long‐term data are being accumulated in this open‐label extension study, which was conducted at 58 sites in 12 European countries. Incidence rates for malignancy and infection may be compared with the background statistics available from large databases.

A summary of results based on 3‐year data in this ongoing study is presented in this report.

Patients and methods

Study design and patients

This is an ongoing, open‐label, multicentre study on the long‐term effects of etanercept in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis despite disease‐modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) treatment. The study started in 1998, after completion of two randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled studies, in which patients received either placebo or etanercept for up to 6 months (fig 1). In the open‐label study, which is expected to continue for up to 5 years, all patients receive etanercept 25 mg twice weekly. The ethics committee of each participating centre approved the study protocol and the consent form. Before entering the open‐label study, each patient gave written informed consent.

Figure 1 Flow chart of patients from the double‐blind studies to the long‐term open‐label study. BIW, twice weekly; ETN, etanercept; QW, once weekly.

To be included in the double‐blind trials, patients had to have failed at least one DMARD, have functional class I, II or III of the American Rheumatism Association criteria for rheumatoid arthritis, and meet the 1987 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria for rheumatoid arthritis. Active rheumatoid arthritis is defined by the presence of ⩾6 swollen joints, ⩾12 tender joints and one of the following criteria: Westergren erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of ⩾28 mm/h, serum C reactive protein (CRP) concentration of >20 mg/l, or morning stiffness for ⩾45 min. Onset of rheumatoid arthritis had to occur after age 16 years, and disease duration ⩽15 years.

Exclusion criteria for the double‐blind studies included relevant concurrent medical disease, including cancer, uncompensated congestive heart failure, active infection, and noticeable laboratory abnormalities. Other exclusion criteria included use of any investigational drug ⩽3 months before screening for the double‐blind studies, use of immunosuppressive agents, or previous administration of an anti‐tumour necrosis factor (TNF) agent other than etanercept. Women with childbearing potential were asked to use contraception during the study. The numbers of patients and etanercept treatment regimens for the two double‐blind studies are shown in fig 1.

Drugs

During the open‐label study, etanercept 25 mg was self‐administered subcutaneously twice weekly. Permitted concomitant drugs include non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs, corticosteroids (⩽10 mg/day prednisolone or equivalent), analgesics, and physical, herbal and homeopathic treatments. No intra‐articular corticosteroid injection was permitted for the first 3 months. Thereafter, the total allowed dose of corticosteroid injection did not exceed the equivalent dose of 40 mg prednisone in any 3‐month period. Treatment with a DMARD or cytotoxic drug was prohibited.

Clinical evaluation

After completion of the double‐blind studies, patients entering the open‐label study were evaluated clinically and variables including swollen and tender joint counts (66/68 counts),7 pain Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ), and patient and physician global assessments of disease activity were considered, at baseline, week 2, week 4 and monthly thereafter. ESR and CRP were assessed at baseline, week 2, week 4, and at 12‐week intervals, thereafter. Patients were evaluated by the same assessor whenever feasible throughout the study.

Safety evaluations, including physical examination, adverse experiences, vital signs, routine blood biochemistry and haematology analysis, were carried out at week 2, week 4, and monthly thereafter, for the first year of the open‐label study and every 3 months thereafter, for the remainder of the study.

An event was considered to be a treatment‐emergent adverse event (TEAE) if it occurred during the study or if the severity or frequency of a pre‐existing event increased during the study. A serious adverse event (SAE) was any event that resulted in death; was life threatening, required hospitalisation, or medical or surgical intervention; resulted in persistent or marked disability, cancer; or was a congenital defect. Infections were serious if they met the definition of an SAE.

The incidence of malignancies was compared with the National Cancer Institute's (NCI) Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)8 database. The age‐specific and sex‐specific incidence rates for cancer from the SEER database were applied to the exposure in this study.

Statistical analyses

In this open‐label study, the emphasis was on descriptive statistics and the primary objectives were safety parameters. The baseline used for safety parameters was the start of the open‐label study. Assessment of clinical efficacy of etanercept was a secondary objective. The main efficacy end points were numbers of painful and swollen joints. Efficacy parameters analysed with the last observation carried forward (LOCF) were based on patients who received at least one dose of etanercept, the intent‐to‐treat population. Baseline values for efficacy parameters were assessed before the start of etanercept treatment—that is, before the double‐blind trials for patients who received etanercept—and before the open‐label study for patients who received placebo during the double‐blind trials.

The power of this study was estimated as the probability of encountering ⩾1 adverse event given a true underlying incidence. With 549 patients, there is a 50% chance that an adverse event with a 0.13% incidence would be observed, an 80% chance for an adverse event with a 0.30% incidence and a 90% chance for one with a 0.44% incidence.

Results

Patient characteristics

Table 1 summarises the characteristics of the patients before treatment.

Table 1 Patient baseline characteristics before treatment.

| Total enrolled | 549 |

| Mean age (years) | 53 |

| Women (%) | 79 |

| Patients on prior NSAIDs (%) | 87 |

| Patients on prior corticosteroids (%) | 84 |

| Mean no of prior DMARDs | 3.3 |

| No of tender joints | 31.0 |

| No of swollen joints | 22.4 |

| RF+ (%) | 86.4 |

| Mean RA duration (years) | 7.4 |

DMARDs, disease‐modifying antirheumatic drugs; NSAIDs, non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; RF, rheumatoid factor.

Exposure

In total 549 adult patients with rheumatoid arthritis received etanercept 25 mg twice weekly. The minimum, maximum and median exposure was 8 days, 3.92 and 3.34 years, respectively. A total of 1396 patient‐years have been accrued in this open‐label study.

Safety and tolerability

Throughout the study, the two most common reasons for discontinuation from etanercept were adverse event and unsatisfactory response (table 2). As on the cut‐off date (31 August 2001), 363 patients continue to receive etanercept in this ongoing trial.

Table 2 Percentage (number) of patients who withdrew (primary reasons).

| Reason for discontinuation | Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | >3 years* | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any reason | 15 (82) | 10 (53) | 8 (43) | 1 (8) | 34 (186) |

| Adverse events | 5 (30) | 4 (20) | 3 (19) | <1 (4) | 13 (73) |

| Unsatisfactory response | 5 (29) | 2 (11) | 3 (16) | <1 (2) | 11 (58) |

| Other non‐medical event | 1 (7) | 3 (14) | <1 (1) | <1 (1) | 4 (23) |

| Patient request | 1 (6) | 1 (6) | <1 (3) | <1 (1) | 3 (16) |

| Protocol violation | 2 (9) | <1 (2) | <1 (2) | 0 (0) | 2 (13) |

| Failed to return | <1 (1) | 0 (0) | <1 (2) | 0 (0) | <1 (3) |

*Till the cut‐off date (31 August 2001).

We found no predominant adverse events leading to discontinuation. The most common adverse events leading to discontinuation were pruritus (n = 4), and abscess, injection‐site reaction, rash, sepsis, pneumonia, myocardial infarction and pyogenic arthritis (n = 3 for each). The most frequently reported TEAEs included upper respiratory infection, accidental injury, injection‐site reaction and flu syndrome (table 3). We found no cases of demyelinating disease of the central nervous system.

Table 3 Most frequently reported treatment‐emergent adverse events.

| Adverse event | % of patients | Events per patient‐year* |

|---|---|---|

| Upper respiratory infection | 38 | 0.34 |

| Accidental injury | 26 | 0.14 |

| Injection‐site reaction | 26 | 0.43 |

| Flu syndrome | 21 | 0.11 |

| Infection | 19 | 0.10 |

| Rash | 17 | 0.09 |

| Abdominal pain | 16 | 0.09 |

| Pharyngitis | 15 | 0.08 |

| Back pain | 15 | 0.08 |

| Bronchitis | 15 | 0.10 |

| Headache | 14 | 0.10 |

| Rhinitis | 14 | 0.08 |

| Diarrhoea | 13 | 0.07 |

| Cough increased | 13 | 0.07 |

| Arthralgia | 11 | 0.06 |

| Hypertension | 11 | 0.05 |

| Urinary tract infection | 11 | 0.07 |

| Injection‐site haemorrhages | 10 | 0.35 |

*Open‐label exposure.

NCI grades (3 and 4) were used to identify patients with test results of potential clinical importance. The most common grade 3 and 4 laboratory abnormalities were increased alanine aminotransferase (n = 12), low lymphocytes (n = 10) and low albumin (n = 9). One patient had low platelet values (lowest value = 35×109/l) for three consecutive visits, but continued in the study. Another patient had increased alanine aminotransferase for two consecutive visits. This patient was withdrawn from the study because of a protocol violation, non‐compliance with study drugs. The remaining patients had transient grade 3 or 4 laboratory abnormalities. No persistent clinically relevant laboratory abnormalities were found. Five patients (0.9%) discontinued because of a laboratory abnormality that was not classified as grade 3 or 4.

Serious infections

Rates of serious infections requiring hospitalisation or requiring parenteral antibiotics remained unchanged over the extended course of the study (table 4). The most frequently reported serious infections were pneumonia, upper respiratory infection, abscess, bronchitis, gastroenteritis, septic arthritis, sepsis, peritonitis and wound infection.

Table 4 Serious infections.

| Years on etanercept | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | 0–1 (n = 549) | 1–2 (n = 468) | 2–>3 (n = 421) | Total (n = 549) |

| Patient‐years | 501 | 446 | 448 | 1396 |

| No of events | 37 | 26 | 26 | 89 |

| Infections per 100 patient‐years | 7.4 | 5.8 | 5.8 | 6.4 |

Of the 10 patients who died during or after discontinuation from the study, 7 had infection as a contributory factor to their deaths (table 5).

Table 5 Deaths: days on treatment and associated conditions.

| Relative days on open‐label treatment | Clinical profile at the time of death |

|---|---|

| 32 | Cardiorespiratory failure after recovery from peritonitis and sepsis* |

| 39 | Disseminated carcinoma, sepsis* |

| 53 | Agranulocytosis (due to thiamazole), sepsis with multiorgan failure* |

| 221 | Renal failure, cholecystitis, cholelithiasis* |

| 716 | Alcoholic hepatitis, pneumonia* |

| 950 | Sudden death, pneumonia* |

| 1007 | Car accident |

| 1131 | Acute heart failure |

| 1149 | Pulmonary embolism |

| 1154 | Cardiac arrest (chronic cardiomyopathy, possibly pulmonary embolism, bacteraemia without clinical symptoms of sepsis)* |

*Associated with infection.

Of the 14 patients with a history of tuberculosis, none experienced tuberculosis reactivation. One case of suspected tuberculosis was reported in a patient in Spain with a history of occupational pneumoconiosis (Caplan's syndrome); this patient had a positive tuberculin test without evidence of mycobacterium.

Malignancies

Among the malignancies reported, no clustering around any specific type of cancer was observed. The most commonly reported tumour types were breast (n = 3) and lung (n = 2) carcinomas. We found one report of lymphoma in a 59‐year‐old patient with disease duration of 4.5 years and 323 days of etanercept treatment. The patient was diagnosed with Hodgkin's lymphoma 8 months after discontinuing etanercept treatment. Because malignancies develop over a long time, the exposure data captured in table 6 included those of the patients treated with etanercept in the double‐blind studies. The rates per patient‐year remained stable throughout the study. Compared with the SEER database, the number of cases observed is lower (n = 11) than the number of cases expected (n = 13), on the basis of etanercept exposure. Because the SEER database8 does not include non‐melanoma skin cancers, the two reports of basocellular skin cancers were excluded from the comparison.

Table 6 Incidence of malignancies.

| Years on etanercept | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | 0–1 (n = 549) | 1–2 (n = 479) | 2–>3 (n = 430) | Total (n = 549) |

| Patient‐years* | 516 | 455 | 527 | 1498 |

| No of events | 3 | 5 | 3 | 11 |

| Malignancies per 100 patient‐years | 0.6 | 1.1 | 0.6 | 0.7 |

*Includes double‐blind and open‐label exposure data for those patients who entered the extension trial.

Expected cases: 13 based on the National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database.

Efficacy

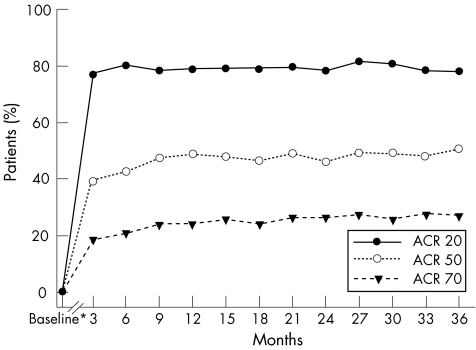

The percentage of patients meeting ACR20 criteria remained relatively stable throughout the trial, and was at 77.8% at month 36. Although not significant, the percentage of patients meeting ACR50 increased with time on etanercept, from 39.5% at month 3 to 50.6% at month 36. Similarly, the ACR70 rate was 18.6% at month 3 and 27.0% at month 36 (fig 2). The mean baseline Disease Activity Score score of 5.1 decreased to 3.0 at month 3 and continued to decrease thereafter (fig 3).

Figure 2 Percentage of patients with American College of Rheumatology (ACR)20, ACR50 and ACR70 response rates by study month. *Baseline of previous double‐blind studies.

Figure 3 Mean Disease Activity Score (DAS) and median Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) scores by study month. *Baseline of previous double‐blind studies.

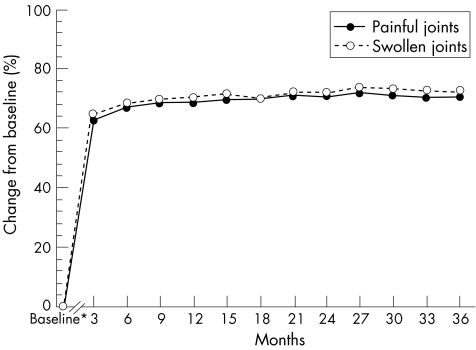

After 3 months of treatment, a substantial reduction in the numbers of painful and swollen joints was achieved, 11.6 (63%) and 8.0 (65%), respectively. At 3 years, the numbers were reduced to 8.9 (71%) and 6.2 (72%), respectively (fig 4).

Figure 4 Percentage change from baseline in the numbers of painful and swollen joints by study month. *Baseline of previous double‐blind studies.

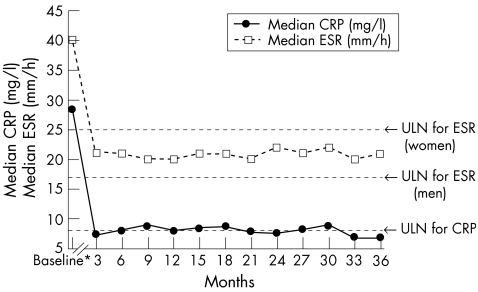

The mean baseline CRP and ESR concentrations were 43.4 mg/l and 44.3 mm/h, respectively. At month 3, they decreased to 17.5 mg/l and 26.2 mm/h, respectively, and at month 36, to 12.1 mg/l and 24.8 mm/h, respectively (fig 5).

Figure 5 Median C reactive protein (CRP) and median erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) by study month. *Baseline of previous double‐blind studies. ULN, upper limit of normal.

The baseline median HAQ score of 1.8 decreased to 1.1 at 3 months and was maintained thereafter; at month 36, the median HAQ score was 1.1, representing a 39% improvement from baseline (fig 3). The mean physician and patient global assessments of 6.6 and 6.7, respectively, at baseline decreased to 2.9 and 3.4, respectively, at month 3, with a small additional improvement by month 36. Patient pain scores improved from baseline by 50% at month 3 and by 49.2% at month 36.

Discussion

This multicentre, open‐label study confirmed that etanercept monotherapy provides a sustained favourable efficacy and safety profile. Retention rates were similar9 or higher10,11,12,13 than those seen in long‐term studies of etanercept and other rheumatoid arthritis treatments. Over the 3 years, patients showed no increase in TEAEs or SAEs, and there were no reports of tuberculosis recurrence. The incidence of malignancy was similar to that of the general population.

One limitation of this multicentre study is its open‐label design—that is, subjects and investigators are not blinded—which could introduce bias. However, it would be inappropriate to consider a placebo‐controlled study to evaluate the long‐term safety and efficacy of a treatment for rheumatoid arthritis. Open‐label studies with careful monitoring and with the option of comparing results between different time periods thus represent one important possibility of obtaining results that are of relevance to the clinical practice.

In our study, 66% of patients were receiving etanercept after 3 years. This retention rate is similar to the 63% observed in a similar long‐term study of North American patients with rheumatoid arthritis.9 Adherence rates for DMARD treatments are available only in published long‐term observational studies. In a 14‐year prospective observational study of 671 patients with rheumatoid arthritis attending an outpatient clinic,12 the approximate percentage of patients remaining on treatment was 55% for methotrexate, 40% for hydroxychloroquine, 39% for penicillamine, 39% for gold injection and 35% for auranofin at 3 years.12 Regardless of study design, patients receiving inadequate or unsatisfactory treatment would have a similar desire to discontinue. Therefore, despite the differences in the studies discussed here, the longer retention rates observed in our open‐label trial suggest that etanercept may be well tolerated or more efficacious than most DMARDs.

In previously reported double‐blind placebo‐controlled studies, the rate of infections with etanercept was not markedly different from that with placebo.2,3,6 Adverse events, including incidence of infection reported in this open‐label study, were comparable with those in the placebo arm of the preceding double‐blind study14 even after 3 years of continuous drug exposure. This safety profile is reassuring, because it has been assumed that long‐term inhibition of TNF would increase the risk of infection.15,16,17 However, the data need to be interpreted with some caution, because this long‐term extension study included patients from two randomised double‐blind trials with strict inclusion and exclusion criteria, which may differ from many clinical practice populations in terms of comorbidities and drugs.

The association between tuberculosis and other intracellular infections with various anti‐TNF treatments is another potential area of concern.18 Although patients with a history of tuberculosis were not excluded from this study, none of the 14 patients with a documented history of tuberculosis had any recurrence or exacerbation of infection during the trial. Tuberculosis was suspected in one patient from Spain who received etanercept treatment for more than 3 years.

Another long‐term potential consequence of TNF inhibition is an increased risk of malignancy secondary to the possible role of TNF in tumorigenesis.19 In this long‐term study, the number of malignancies per patient‐year, including skin cancers, was reported to be 0.009. Although study designs differed, rates of malignancies were similar to those obtained from a long‐term follow‐up of 521 patients with rheumatoid arthritis at the Mayo Clinic (Rochester, Minnesota, USA) (0.018)20 and a controlled retrospective cohort study of 623 patients with rheumatoid arthritis in The Netherlands (0.012).21 Furthermore, in a register‐based study in Sweden on patients subject to treatment with TNF‐blocking agents in clinical practice, the standardised incidence ratio (observed/expected numbers of cancers) was 0.9 (95% CI 0.7 to 1.2).22

The number of observed cases (n = 11) of malignancy is fewer than that expected (n = 13) based on the age‐matched and sex‐matched general population from the NCI SEER8 database, a database of cancers (not including non‐melanoma skin cancers) that have been reported in North America. The SEER database was used to provide an approximation of the rate of malignancies in the general population worldwide. Although not specific for Europe, this database provides approximate rates of malignancy in the general population. The incidence of malignancy was relatively constant in each of the 3 years of treatment, with no unusual clustering of any particular cancer. The one reported case of lymphoma had a questionable relationship to etanercept: the patient had received almost 11 months of etanercept and developed Hodgkin's lymphoma 8 months after discontinuation. Overall, it seems that the malignancies among this patient population are representative of a chronic rheumatoid arthritis population.

Although the designs of the studies listed in table 7 were different, mortality was consistent. The rate of seven infection‐related deaths per 1498 patient‐years is comparable with infection‐related mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis from published sources and a large US registry (table 7).21,23,24,25

Table 7 Infection‐related mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

| Source | Year of publication | No of patients | Estimated exposure (patient‐years) | Estimated mortality per 100 patient‐years |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| This report (Europe) | 2006 | 549 | 1498* | 0.47 |

| Duthie et al (UK) | 1964 | 307 | 2240 | 0.49 |

| Prior et al (UK) | 1984 | 448 | 5018 | 0.64 |

| Wolfe et al (US)25 | 1994 | 3501 | 29 200 | 0.62 |

| van den Borne et al (The Netherlands)21 | 1998 | 415 | 2280 | 0.39 |

*Includes both double‐blind and open‐label etanercept exposure.

The extent to which the infections were associated with the fatal outcome is not clear because most patients had other comorbid conditions. Studies have shown that patients with rheumatoid arthritis have higher mortality than the general population.26 Gabriel et al27 reported that the risk of mortality is approximately 38% greater in patients with rheumatoid arthritis than in the general population. The risk was dramatically higher at 55% in women with rheumatoid arthritis than in the general population.27 Wolfe et al25 reported 4–13 times higher infection‐related mortality for patients with rheumatoid arthritis than for the general population. For pneumonia, the mortality was 3–6 times higher for patients with rheumatoid arthritis.25

Another concern in connection with anti‐TNF treatment is central demyelination. Although reports have described how TNF inhibitors could worsen demyelinating conditions,28 there were no reports of demyelinating disease of the central nervous system (eg, multiple sclerosis or optic neuritis) in this long‐term study. However, more long‐term etanercept exposure is required before a full assessment can be made.

The overall treatment response from any of the efficacy variables, including Disease Activity Score, was attained early and maintained throughout the 3‐year period. These results are in agreement with a North American long‐term open‐label study, which showed that the efficacy of etanercept is sustained and well tolerated.10 Both studies enrolled similar DMARD‐refractory patients, who were not allowed to receive other antirheumatic drugs during the trial. Consequently, the results achieved in this study do not reflect the potential additive effects of combination therapy.

Improvement in the signs and symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis occurred early and were sustained over the 3‐year period. An ACR20 response rate ⩾75% was achieved and maintained from 3 to 36 months. This was similar to US long‐term data, in which 73% and 76% of patients treated with etanercept achieved ACR20 response rate at 30 months10 and ∼48 months.29 ACR50 and ACR70 response rates of 39.5% and 18.6%, respectively, seen 3 months after the start of the open‐label extension, tended to increase over the 36 months. The ACR50 results are consistent with previously reported response rates in a double‐blind, controlled trial.5 ACR70 response rate at 3 months is higher than that observed after 3 months in other double‐blind trials. One possible explanation is that patients entering the open‐label trial were not etanercept‐naive; they had received 1–6 months of treatment during the double‐blind trial. Another potential factor is the open‐label design; patients have a more positive response when they know they are receiving active drugs.

One of the challenges encountered when designing a long‐term study is accounting for missing data points or discontinuations before the end of the study. We chose to use the LOCF to capture the early responders who discontinued for reasons other than lack of efficacy. An analysis including only the patients completing 3 years could introduce bias because these patients were more likely to be treatment responders. In our study, ACR response rates derived using a completers analysis were higher than the rates derived using an LOCF analysis; percentages of ACR20, ACR50 and ACR70 responders were 85.9%, 59.1% and 31.8%, respectively, at 3 years.

Similar sustained responses were seen with the quality‐of‐life measures on disability functions; the mean percentage change from baseline for the HAQ score was improved by 40.7% at 3 months and maintained for 3 years. These results are clinically relevant because patients with rheumatoid arthritis experience varying degrees of physical impairment, fatigue, reactive depression and weight loss.30

In conclusion, etanercept shows a favourable safety and efficacy profile for >3 years of treatment, and continues to provide significant clinical benefit in the patient population evaluated in this study. Etanercept represents a long‐term treatment option in clinical practice.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Wyeth Research, Collegeville. We thank Pamela Yeh, PharmD, Donna Simcoe, MS, and Ruth Pereira, PhD, for assistance with the preparation of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

ACR - American College of Rheumatology

CRP - C reactive protein

ESR - erythrocyte sedimentation rate

HAQ - Health Assessment Questionnaire

LOCF - last observation carried forward

NCI - National Cancer Institute

SAE - serious adverse event

SEER - Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results

TEAE - treatment‐emergent adverse event

TNF - tumour necrosis factor

Footnotes

Competing interests: LK has received research grants and has been consultant and speaker on symposia arranged by Wyeth, Schering Plough, Abbott, Bristol Myers Squibb and Amgen. VR‐V has participated in clinical trials sponsored by Abbott, Schering Plough, Wyeth, and has given lectures paid by Schering Plough and Wyeth. MD has been paid by Wyeth for running educational programmes, and has received grants from Wyeth for conducting research. MG is a paid participating investigator and has given lectures for Wyeth Research. JW is an employee of Wyeth Research.

References

- 1.Bathon J M, Martin R W, Fleischmann R M, Tesser J R, Schiff M H, Keystone E C.et al A comparison of etanercept and methotrexate in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis [comment] [erratum appears in N Engl J Med 2001;344:240]. N Engl J Med 20003431586–1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weinblatt M E, Kremer J M, Bankhurst A D, Bulpitt K J, Fleischmann R M, Fox R I.et al A trial of etanercept, a recombinant tumor necrosis factor receptor:Fc fusion protein, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving methotrexate. N Engl J Med 1999340253–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moreland L W, Schiff M H, Baumgartner S W, Tindall E A, Fleischmann R M, Bulpitt K J.et al Etanercept therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 1999130478–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Genovese M C, Bathon J M, Martin R W, Fleischmann R M, Tesser J R, Schiff M H.et al Etanercept versus methotrexate in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: two‐year radiographic and clinical outcomes. Arthritis Rheum 2002461443–1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klareskog L, van der Heijde D, de Jager J P, Gough A, Kalden J, Malaise M.et al Therapeutic effect of the combination of etanercept and methotrexate compared with each treatment alone in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 2004363675–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moreland L W, Baumgartner S W, Schiff M H, Tindall E A, Fleischmann R M, Weaver A L.et al Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with a recombinant human tumor necrosis factor receptor (p75)‐Fc fusion protein [comment]. N Engl J Med 1997337141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Felson D T, Anderson J J, Boers M, Bombardier C, Chernoff M, Fried B.et al The American College of Rheumatology preliminary core set of disease activity measures for rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials. The Committee on Outcome Measures in Rheumatoid Arthritis Clinical Trials. Arthritis Rheum 199336729–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program Public‐Use Data (1973–1999) [11 Registries, 1992–1999)]. National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, Cancer Statistics Branch, released April 2002, based on the November 2001 submission

- 9.Genovese M C, Bathon J M, Fleischmann R M, Moreland L W, Martin R W, Whitmore J B.et al Longterm safety, efficacy, and radiographic outcome with etanercept treatment in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2005321232–1242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moreland L W, Cohen S B, Baumgartner S W, Tindall E A, Bulpitt K, Martin R.et al Long‐term safety and efficacy of etanercept in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2001281238–1244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morand E F, McCloud P I, Littlejohn G O. Continuation of long term treatment with hydroxychloroquine in systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 1992511318–1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolfe F, Hawley D J, Cathey M A. Termination of slow acting antirheumatic therapy in rheumatoid arthritis: a 14‐year prospective evaluation of 1017 consecutive starts. J Rheumatol 199017994–1002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalden J R, Schattenkirchner M, Sorensen H, Emery P, Deighton C, Rozman B.et al The efficacy and safety of leflunomide in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: a five‐year followup study. Arthritis Rheum 2003481513–1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klareskog L, Wajdula J, Pedersen R. A long‐term open‐label trial of the safety and efficacy of etanercept (25 mg twice weekly) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (interim analysis) [abstract]. Ann Rheum Dis 200161FRI0050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Havell E A. Evidence that tumor necrosis factor has an important role in antibacterial resistance. J Immunol 19891432894–2899. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flynn J L, Goldstein M M, Chan J, Triebold K J, Pfeffer K, Lowenstein C J.et al Tumor necrosis factor‐alpha is required in the protective immune response against Mycobacterium tuberculosis in mice. Immunity 19952561–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laichalk L L, Kunkel S L, Strieter R M, Danforth J M, Bailie M B, Standiford T J. Tumor necrosis factor mediates lung antibacterial host defense in murine Klebsiella pneumonia. Infect Immun 1996645211–5218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gershon S, Wise R P, Niu M, Siegel J. Postlicensure reports of infection during use of etanercept and infliximab. Arthritis Rheum 2000432857 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aggarwal B B. Signalling pathways of the TNF superfamily: a double‐edged sword. Nat Rev Immunol 20033745–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katusic S, Beard C M, Kurland L T, Weis J W, Bergstralh E. Occurrence of malignant neoplasms in the Rochester, Minnesota, rheumatoid arthritis cohort. Am J Med 19857850–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van den Borne B E, Landewe R B, Houkes I, Schild F, van der Heyden P C, Hazes J M.et al No increased risk of malignancies and mortality in cyclosporin A‐treated patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1998411930–1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Askling J, Fored C M, Brandt L, Baecklund E, Bertilsson L, Feltelius N.et al Risks of solid cancers in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and after treatment with tumour necrosis factor antagonists. Ann Rheum Dis 2005641421–1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duthie J R, Brown P E, Truelove L H, Baragar F D, Lawrie A J. Course and prognosis in rheumatoid arthritis: a further report. Ann Rheum Dis 196423193–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prior P, Symmons D P, Scott D L, Brown R, Hawkins C F. Cause of death in rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol 19842392–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolfe F, Mitchell D M, Sibley J T, Fries J F, Bloch D A, Williams C A.et al The mortality of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 199437481–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doran M F, Gabriel S E. Infections in rheumatoid arthritis—a new phenomenon? J Rheumatol 2001281942–1943. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gabriel S E, Crowson C S, O'Fallon W M. Mortality in rheumatoid arthritis: have we made an impact in 4 decades? [see comments]. J Rheumatol 1999262529–2533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mohan N, Edwards E T, Cupps T R, Oliverio P J, Sandberg G, Crayton H.et al Demyelination occurring during anti‐tumor necrosis factor alpha therapy for inflammatory arthritides. Arthritis Rheum 2001442862–2869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Genovese M, Martin R, Fleischmann R, Keystone E, Bathon J, Finck B.et al Etanercept (Enbrel) in early erosive rheumatoid arthritis (ERA trial): observations at 3 years [abstract]. Arthritis Rheum 200144(Suppl)S78 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kosinski M, Kujawski S C, Martin R, Wanke L A, Buatti M C, Ware J E., Jret al Health‐related quality of life in early rheumatoid arthritis: impact of disease and treatment response.Am J Manage Care 20028231–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]