Abstract

Objective

To evaluate whether exercise treatment based on behavioural graded activity comprising booster sessions is a cost‐effective treatment for patients with osteoarthritis of the hip and/or knee compared with usual care.

Methods

An economic evaluation from a societal perspective was carried out alongside a randomised trial involving 200 patients with osteoarthritis of the hip and/or knee. Outcome measures were pain, physical functioning, self‐perceived change and quality of life, assessed at baseline, 13, 39 and 65 weeks. Costs were measured using cost diaries for the entire follow‐up period of 65 weeks. Cost and effect differences were estimated using multilevel analysis. Uncertainty around the cost‐effectiveness ratios was estimated by bootstrapping and graphically represented on cost‐effectiveness planes.

Results

97 patients received behavioural graded activity, and 103 patients received usual care. At 65 weeks, no differences were found between the two groups in improvement with respect to baseline on any of the outcome measures. The mean (95% confidence interval) difference in total costs between the groups was −€773 (−€2360 to €772)—that is, behavioural graded activity resulted in less cost but this difference was non‐significant. As effect differences were small, a large incremental cost‐effectiveness ratio of €51 385 per quality adjusted life year was found for graded activity versus usual care.

Conclusions

This study provides no evidence that behavioural graded activity is either more effective or less costly than usual care. Yielding similar results to usual care, behavioural graded activity seems an acceptable method for treating patients with osteoarthritis of the hip and/or knee.

Osteoarthritits of the hip and/or knee is a common joint disorder. The incidence in general practices in The Netherlands is 2.1/1000 per year for osteoarthritis of the hip and 3.6/1000 per year for the knee.1 Treatment is directed at pain relief and prevention of disability. A systematic review of several randomised trials showed that exercise treatment for irrecoverable chronic diseases such as osteoarthritis has a short‐term positive effect on pain and daily functioning.2 However, this effect seems to decline over time and finally disappear, resulting in a recurring need for treatment, increased disability, work absenteeism and healthcare use.2,3 Maintaining the short‐term benefits of exercise treatment is therefore important.

This study is a cluster randomised controlled trial that investigates whether behavioural graded activity—that is, a behavioural treatment integrating the concepts of operant conditioning with exercise treatment comprising booster sessions—consolidates the positive short‐term effects of usual exercise treatment. The clinical study showed a positive long‐term effect of behavioural graded activity.4 Contrary to previous findings, however, this positive effect is also found for usual exercise treatment, leading to insignificant effect differences between the treatment groups.

As treatment of osteoarthritis may lead to considerable costs, it is important that the clinical evaluation of a new treatment programme is accompanied by an economic evaluation. In this paper, we present a cost‐effectiveness analysis of the behavioural graded activity programme in comparison with usual exercise treatment.

Methods

Study design

An economic evaluation was conducted alongside a cluster randomised controlled trial comparing behavioural graded activity and usual care according to the Dutch Osteoarthritis guidelines of the Royal Dutch College for Physiotherapy. Effectiveness and cost effectiveness over 65 weeks were investigated. The study was approved by the medical ethical committee of the VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Study population

In all, 87 physiotherapists, willing and able to participate in the study, were recruited. Participating physiotherapeutic practices were randomly assigned to one of the two treatment programmes. As recruitment of patients through participating physiotherapists was slow, a second recruitment strategy was used—that is, patients responded to articles in local newspapers about the benefit of exercise treatment and the study performed. Patients recruited thus were referred to a participating physiotherapist. A description of the recruitment strategies and the influence on the study population is published elsewhere.5 Patients were included if they fulfilled the clinical criteria of the American College of Rheumatology for osteoarthritis of the hip or knee.6,7 All patients willing and eligible to participate gave their informed consent. In total, 200 patients were included. For more details on the trial, refer to Veenhof et al.4

Interventions

The behavioural graded activity group received a treatment integrating the concepts of operant conditioning with exercise treatment comprising booster sessions. Graded activity was directed at increasing the level of activity in a time‐contingent manner, with the goal of integrating these activities in the daily lives of patients.4,8,9 Treatment consisted of a 12‐week period with a maximum of 18 sessions, followed by 5 preset booster moments with a maximum of 7 sessions (in weeks 18, 25, 34, 42 and 55, respectively).

The usual care group received treatment according to the Dutch physiotherapy guideline for patients with osteoarthritis of hip and/or knee.10 This guideline consists of general recommendations, emphasising provision of information and advice, exercise treatment and encouragement of coping positively with the complaints. Treatment consisted of a 12‐week period with a maximum of 18 sessions and could be discontinued within this 12‐week period if, according to the physiotherapist, all treatment goals had been achieved.

Clinical outcome measures

Patients completed health questionnaires at baseline, 13, 39 and 65 weeks. The primary outcome measures were pain (Visual Analogue Scale and Western Ontario and McMaster Universities (WOMAC)), physical function (WOMAC) and self‐perceived change (Patient Global Assessment) according to the core set of outcome measures of clinical trials with patients with osteoarthritis defined by Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT) III.11,12,13 For the cost‐effectiveness analysis, health‐related quality of life (EuroQol‐5D) was also measured.14

Assessment of resource use

Patients provided data on the direct costs of osteoarthritis within and outside the healthcare sector and on the indirect costs of productivity loss. Patients recorded resource use per week in cost diaries, covering the periods 1–12, 13–24, 25–36, 37–38, 39–50, 51–62 and 63–65 weeks. Important resources used within the healthcare sector were physiotherapeutic treatment and osteoarthritis‐related hospitalisation. Resource use outside the healthcare sector included alternative treatment and informal care by friends or family members. Indirect costs of productivity loss were estimated by measuring absenteeism from paid and unpaid work.

Valuation of healthcare consumption; unit costs

The economic evaluation was conducted from a societal perspective. As the study was carried out between 2002 and 2004, 2003 prices were used. Owing to the short follow‐up period, no discounting was applied. Standard prices were used to value most resources considered (table 1).15,16 Prices of drugs were obtained from the Royal Dutch Society for Pharmacy.17 Absenteeism from paid work was valued with the friction cost method—that is, only absenteeism during a friction period needed to replace a person is taken into account.18 Production loss was valued using mean age‐specific and sex‐specific incomes of the Dutch population.15 Using the shadow price method, unpaid work was valued at the cost of the professional required if the unpaid workers were unavailable.15,19 The shadow price of voluntary work and informal care was assumed to be equal to the tariff for cleaning work.

Table 1 Costs per unit healthcare resource used in the economic evaluation of behavioural graded activity (year 2003).

| Healthcare resource (unit) | Cost per unit (€) |

|---|---|

| General practice consultation | |

| General practitioner (visit) | 20.20 |

| Physiotherapist (session) | 22.75 |

| Manual therapist (session) | 31.46 |

| Outpatient attendance | |

| Polyclinic care (visit) | 56.00 |

| Specialist care (visit) | 98.00 |

| Diagnostic procedures | |

| x Ray | 39.00 |

| MRI | 255.29 |

| CT scan | 98.00 |

| Hospital inpatient stay | |

| Hospital admission (day) | 337.00 |

| Replacement knee | 1962.42 |

| Replacement hip | 2061.68 |

| Other | |

| Absenteeism paid labour (h) | 34.98* |

| Absenteeism unpaid labour (h) | 8.30† |

| Professional home care (h) | 21.70 |

| Informal care (h) | 8.30† |

CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

*Average cost per hour according to the friction cost method. In the analysis, sex‐dependent and age‐dependent costs are used.

†Shadow price, being equal to the hour price for cleaning work.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out on an intention‐to‐treat principle. We imputed missing data for patients with an incomplete set of cost diaries using the expectation maximisation algorithm in SPSS V.12.0.1.20 This is an iterative optimisation method to estimate missing data given available data.

Patients treated by the same physiotherapist formed clusters in the trial. Such clustered data require multilevel analysis, which we performed using MlwiN.21,22 The resulting cost and effect differences between treatment groups are corrected for dependence between patients treated by the same physiotherapist.

As cost data are typically skewed, confidence intervals (CI) for cost differences cannot be estimated with conventional methods that assume normality. We therefore applied the non‐parametric bootstrap method—that is, 1000 samples of the same size as the original dataset were sampled with replacement from the data.23,24,25 These resamples were used to estimate 95% confidence interval (CI).

For the cost‐effectiveness analysis, the difference in total cost between the two treatment groups was compared with the difference at 65 weeks relating to improvements in Visual Analogue Scale and WOMAC Scores, percentage improved according to Patient Global Assessment and percentage responders obtained from applying the OMERACT–Osteoarthritis Research Society International response criteria to the outcome measures of this trial.26 The ratings of Patient Global Assessment were assessed by patients on an 8‐point scale (1, vastly worsened; 8, completely recovered) and dichotomised as improved (“completely recovered” to “much improved”) versus not improved (“slightly improved” to “vastly worsened”). To compare the difference in total cost with the difference in quality‐of‐life years gained over 65 weeks, the scores on the EuroQol‐5D were translated into a utility using preferences of the UK general population.27 The utilities of patients at baseline, 13, 39 and 65 weeks were used as weights for the periods 0–13, 13–39 and 39–65 weeks in the trial, giving the total quality‐adjusted life years (QALYs).28,29 Uncertainty around the cost‐effectiveness ratios was estimated using the bias‐corrected and accelerated bootstrapping method (5000 replications) and presented in a cost‐effectiveness plane.24,30

Sensitivity analyses were carried out to study the effect of different imputation strategies. Firstly, we imputed zero costs if data were missing for the last half of the follow‐up period. Secondly, we imputed mean costs for missing data. Also, a complete case analysis was carried out, considering only the patients who completed all cost diaries. To investigate the effect of outliers, we performed an analysis in which 5% of patients with total costs >€11 000 were excluded. The threshold of €11 000 was chosen after inspection of the data of patients with extremely high costs of absenteeism from either paid or unpaid work.

Per‐protocol analyses were performed, both for the complete cases and for the dataset completed by expectation maximisation imputation, in which all patients with deviations from the treatment protocol were excluded. Deviations were defined as <6 sessions of physiotherapy within the first 12 weeks (both groups), or <2 booster sessions (graded activity group) after the first 12 weeks, or a total hip/knee replacement during the whole study period (both groups).

Results

Clinical outcomes

At baseline, no differences in clinical characteristics and in paid/unpaid work were found between the behavioural graded activity and the usual care group. Both groups showed beneficial effects in the long term. However, no differences in improvement between the two groups were found on any of the outcome measures (table 2). Full details on the clinical outcomes are presented in the clinical paper.4

Table 2 Mean cost (€) and effect differences between treatment groups and cost‐effectiveness ratios for all patients (missing data imputed).

| Effect measure | Behavioural graded activity—usual care | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cost difference* | Effect difference* | ICER (95% CI) | |

| QALYs (EuroQol; n = 87/92) | −1028 | −0.02 | 51385 (− 104674 to 1663872) |

| WOMAC pain (scale 0–20; n = 83/91) | −942 | 0.60 | −1575 (−103391 to 3854) |

| WOMAC physical (scale 0–68; n = 77/89) | −813 | −0.17 | 4701 (484 to 299159 |

| VAS pain now (scale 0–10; n = 84/91) | −952 | 0.27 | −3476 (−652950 to 869) |

| VAS pain past week (scale 0–10; n = 84/89) | −1016 | 0.13 | −7699 (−8101771 to −1865) |

| PGA (% improved; n = 83/87) | −1005 | 6.5 | −15462 (−4732743 to 9039)† |

| Responders OARSI criteria (%; n = 90/100) | −773 | 6.5 | −11886 (−1484690 to 697)† |

ICER, Incremental cost‐effectiveness ratio; OARSI, Osteoarthritis Research Society International; PGA, Patient Global Assessment Scale; QALY, quality‐adjusted life years; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale; WOMAC, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities.

*Cost and effect difference corrected for clustering within the factor physiotherapist.

†Incremental cost per patient improved/responder.

Resource use

Ten patients never returned any cost diary and were excluded from the evaluation. These patients did not differ from the remaining 190 patients with respect to baseline characteristics and effect of treatment on primary outcome measures. The remaining 190 patients returned 84% of the cost diaries. Only 64% of the patients completed all diaries. For these patients, table 3 lists the use of healthcare resources and absenteeism from paid and unpaid work. Note that the remainder of the paper focuses on the expectation maximisation imputed data.

Table 3 Reported healthcare use for patients with complete cost data over 65 weeks by treatment group.

| Behavioural graded activity (n = 56) | Usual care (n = 66) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | n | |

| Healthcare sector | ||||

| General practice consultation | ||||

| General practitioner (visits) | 1.4 (2.2) | 27 | 1.5 (2.7) | 35 |

| Physiotherapist (sessions) | 18.0 (16.7) | 53 | 20.2 (14.6) | 66 |

| Other allied healthcare (sessions) | 0.5 (1.8) | 12 | 0.2 (1.1) | 10 |

| Outpatient attendance | ||||

| Polyclinic care (visits) | 0.2 (1.6) | 2 | 0.2 (0.9) | 4 |

| Specialist care (visits) | 0.6 (1.6) | 12 | 1.4 (2.6) | 28 |

| Diagnostic procedures | ||||

| x Ray (n) | 0.6 (1.3) | 22 | 0.9 (1.4) | 33 |

| MRI (n) | 0.1 (0.3) | 4 | 0.1 (0.4) | 6 |

| Other (n) | 0.1 (0.4) | 5 | 0.2 (0.6) | 11 |

| Hospital inpatient stay | ||||

| Hospital admissions (days) | 0.1 (0.9) | 2 | 1.1 (3.0) | 12 |

| Replacement knee (n) | 0.02 (0.1) | 1 | — | 0 |

| Replacement hip (n) | — | 0 | 0.2 (0.4) | 9 |

| Outside healthcare sector | ||||

| Complementary or alternative therapist (sessions) | 0.5 (3.0) | 4 | 0.3 (1.6) | 4 |

| Absenteeism paid labour (h) | 2.6 (17.4) | 3 | 5.4 (19.9) | 11 |

| Absenteeism unpaid labour (h) | 59.1 (156.1) | 15 | 49.5 (112.0) | 32 |

| Informal care (h) | 32.7 (79.0) | 13 | 18.9 (45.7) | 20 |

| Housekeeper (h) | 19.4 (57.3) | 10 | 15.2 (60.3) | 10 |

MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

The last column (n) indicates the number of patients with resource use.

Behavioural graded activity was associated with less medical–specialist care, hospitalisation, hip replacements and absenteeism from paid work compared with usual care, but with more informal care and help in housekeeping. The differences were small and not statistically significant. One interesting detail in table 3 is the small number of patients with work absenteeism in the behavioural graded activity group.

Costs

Table 4 shows the mean (standard deviation (SD)) costs for the two groups. Compared with the usual care group, we observed lower direct healthcare costs and higher costs outside the healthcare sector in the behavioural graded activity group. Total direct costs were similar. From the direct healthcare costs, a substantial part was attributable to hospitalisation. In the usual care group, these costs doubled those in the graded activity group, but this difference was not significant. Indirect costs in the graded activity group were roughly half those in the usual care group. This difference, caused by differences in work absenteeism, was not significant. The difference in total costs was −€773 (95% CI −€2360 to €772), €2530 (SD €4888) for behavioural graded activity and €3341 (SD €5055) for usual care. This difference was not significant.

Table 4 Mean (SD) costs (€) over 65 weeks by treatment group for all patients (missing data imputed).

| Behavioural graded activity* (n = 90) | Usual care* (n = 100) | Difference (95% CI)† | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Healthcare sector | |||

| Primary care costs | 462 (354) | 519 (327) | −57 (−142 to 35) |

| General practitioner | 28 (41) | 33 (50) | −5 (−18 to 9) |

| Allied healthcare | 433 (341) | 486 (318) | −53 (−144 to 36) |

| Secondary care costs | 463 (1095) | 813 (1761) | − 350 (−742 to 83) |

| Polyclinic care | 13 (144) | 8 (41) | 5 (−13 to 24) |

| Specialist care | 71 (82) | 127 (244) | −55 (−114 to 3) |

| Diagnostic procedures | 73 (138) | 76 (141) | −3 (−36 to 31) |

| Hospitalisation | 306 (999) | 603 (1522) | −297 (−666 to 74) |

| Drugs costs | 41 (92) | 57 (128) | −16 (−50 to 18) |

| Professional home care costs | 67 (314) | 178 (650) | −110 (−254 to 34) |

| Direct healthcare costs | 1033 (1334) | 1567 (2160) | −534 (−2261 to 672) |

| Outside healthcare sector | |||

| Complementary or alternative treatment | 48 (174) | 30 (136) | 18 (−27 to 63) |

| Informal care | 212 (542) | 135 (318) | 77 (−51 to 200) |

| Housekeeper | 524 (1416) | 290 (1133) | 230 (−130 to 598) |

| Direct costs outside healthcare sector | 783 (1641) | 455 (1282) | 330 (−80 to 723) |

| Total direct costs | 1816 (2628) | 2022 (2671) | −205 (−958 to 516) |

| Absenteeism paid labour | 462 (2991) | 1041 (3705) | −578 (−1596 to 334) |

| Absenteeism unpaid labour | 251 (873) | 278 (734) | −15 (−442 to 447) |

| Indirect costs | 714 (3208) | 1319 (4888) | −600 (−1763 to 493) |

| Total costs | 2530 (4888) | 3341 (5055) | −773 (−2360 to 772) |

*Raw estimates.

†Difference corrected for clustering within the factor physiotherapist with 95% CI obtained from a non‐parametric bootstrap method with 1000 replications.

Cost effectiveness

Table 5 shows the total costs and effects at 65 weeks for the different outcome measures. Table 2 shows the differences in total costs and effects, the incremental cost‐effectiveness ratios and their 95% CIs.

Table 5 Mean costs (€) and effects by treatment group for all patients (missing data imputed).

| Effect measure | Behavioural graded activity | Usual care | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Costs | Effects | Costs | Effects | |

| QALYs (EuroQol; n = 87/92) | 2375 | 0.71 | 3440 | 0.73 |

| WOMAC pain (scale 0–20; n = 83/91) | 2418 | 3.67* | 3400 | 3.14* |

| WOMAC physical (scale 0–68; n = 77/89) | 2284 | 7.03* | 3169 | 7.29* |

| VAS pain now (scale 0–10; n = 84/91) | 2410 | 0.85* | 3400 | 0.57* |

| VAS pain past week (scale 0–10; n = 84/89) | 2410 | 1.92* | 3458 | 1.79* |

| PGA (% improved; n = 83/87) | 2435 | 54 | 3483 | 48 |

| Responders OARSI criteria (%; n = 90/100) | 2530 | 46 | 3341 | 42 |

OARSI, Osteoarthritis Research Society International; PGA, Patient Global Assessment Scale; QALY, quality‐adjusted life years; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale; WOMAC, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities.

*A positive sign indicates improvement compared with baseline.

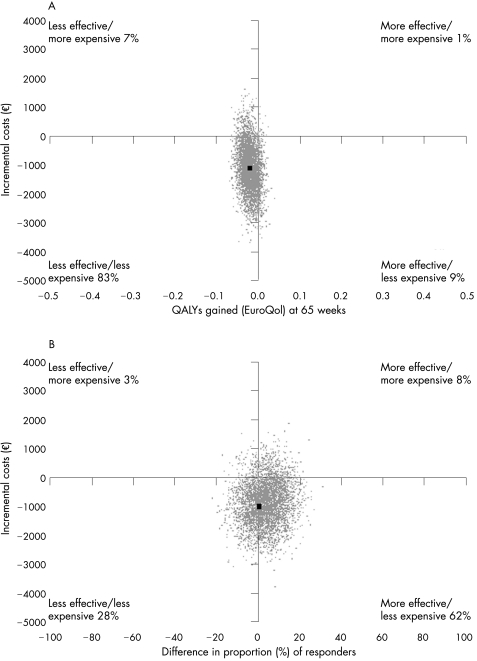

Considering the scale of the outcome measures, the effect differences were close to zero. Therefore, large cost‐effectiveness ratios with large CIs were found. The incremental cost‐effectiveness ratio for QALYs gained was €51 385 per QALY. The difference in QALYs over 65 weeks being negative, this incremental cost‐effectiveness ratio means that implementing graded behavioural activity yields €51 385 per QALY that is lost by not giving usual care. Figure 1A shows the cost‐effectiveness plane for QALYs gained. In all, 92% of the cost‐effect pairs lie below the x axis, the area where behavioural graded activity is associated with lower costs.

Figure 1 (A) Cost‐effectiveness plane for quality‐adjusted life years (QALYs) gained at 65 weeks for behavioural graded activity versus usual care. (B) Cost‐effectiveness plane for the difference, at 65 weeks, in the proportion of responders according to the Outcome Measures in Rheumatology–Osteoarthritis Research Society International response criteria for behavioural graded activity versus usual care.

The cost‐effectiveness ratio for responders according to the OMERACT–Osteoarthritis Research Society International criteria was −€11 886 per responder, meaning that implementing behavioural graded activity yields €11 886 per additional treatment responder due to behavioural graded activity. Figure 1B shows the corresponding cost‐effectiveness plane. For 90% of the cost–effect pairs, the costs of behavioural graded activity are lower.

Sensitivity analysis

Uncorrected cost differences were similar to cost differences corrected for clustering of patient data. The uncorrected difference in total costs was −€811 (95% CI −€2106 to €946). When excluding 11 patients with total costs exceeding €11 000, from the analysis, we found a difference in total cost of −€740 (95% CI −€1447 to €72). Considering only patients with complete follow‐up resulted in a difference in total costs of −€1096 (95% CI −€3105 to € 819). When zero costs were imputed for missing cost diaries in the last half of the follow‐up period, the difference in total costs was −€889 (95% CI −€2601 to €857). Imputation of mean costs for missing cost diaries resulted in a difference of −€627 (95% CI (−€1846 to €824).

Per‐protocol analysis

About 20 patients from the graded activity group and 10 from the usual care group were excluded from the per‐protocol analysis. Mean difference in total costs between the groups was −€987 (95% CI −€2777 to €786). For patients with complete follow‐up on cost data, this difference was −€1057 (95% CI −€3308 to €834; n = 45/60).

Discussion

Differences in direct and indirect costs between the behavioural graded activity and usual care group were not statistically significant. However, with the exception of direct costs outside the healthcare sector, costs in the behavioural graded activity group were consistently lower than in the usual care group. This was particularly true for the indirect costs of absenteeism. This cannot be explained by a difference in the number of patients with paid work at baseline in the two groups (28% v 29%), nor by the higher hospitalisation rate in the usual care group (ie, no significant relationship between hospitalisation and work absenteeism was found). Possibly, the behavioural component of the graded activity programme leads to less avoidance behaviour, so that patients are less inclined to refrain from working.

In the usual care group, a higher hospitalisation rate was observed. This cannot be explained by baseline differences between the groups. Although this raises the question of whether behavioural graded activity reduces the need for surgery, we believe that the observed difference is most likely due to chance.

Interestingly, the two groups are associated with similar costs for allied healthcare. Apparently, the graded activity protocol, prescribing more treatment sessions than the usual care programme, did not result in more treatment sessions.

Total costs were lower in the behavioural graded activity group. However, the difference in total costs (−€773) was surrounded by large confidence bounds (95% CI −€2360 to €772) and may thus be coincidental.

The effect differences between the two treatment groups on any of the outcome measures were extremely small, and the sign of these differences seems of no importance. As such, it is hard to interpret the cost‐effectiveness ratios and it seems more reasonable to base conclusions on cost differences rather than on cost effectiveness.

The results of this cost‐effectiveness study are possibly confounded by the two different strategies that were used to recruit patients. Veenhof et al5 concluded that the different strategies lead to different baseline characteristics, but the treatment effect after adjustment for these characteristics was similar for all outcome measures. In addition, Veenhof et al4 showed that baseline characteristics in the two treatment groups were similar, and the difference in treatment effect did not change after adjusting for baseline characteristics. As such, we conclude that it is unlikely that our cost‐effectiveness results are confounded by having used two different recruitment strategies.

Earlier publications on the cost effectiveness of different types of exercise treatment for osteoarthritis of the hip and/or knee are not available. In a study by Van Baar,3 exercise treatment in combination with advice and drugs was compared with advice and drugs only. As this study focuses on treatment modules other than our study, it is hard to compare the results.

In conclusion, this study provides no evidence that behavioural graded activity for patients with osteoarthritis of the hip and/or knee is either more effective or less costly than usual care. Yielding similar results, behavioural graded activity seems an acceptable method for treating patients with osteoarthritis of the hip and/or knee.

Acknowledgements

We thank the physiotherapists and patients for participating in this study.

Abbreviations

OMERACT - Outcome Measures in Rheumatology

QALY - quality adjusted life year

WOMAC - Western Ontario and McMaster Universities

Footnotes

Funding: This study was supported by a grant from the Dutch Health Care Insurance Board.

Competing interests: None.

References

- 1.Miedema H. Reuma‐onderzoek meerdere echelons (Rome): basisrapport. (Rheumatism‐research on different levels of the health care system: basis report), NIPG‐publication 93.099. Leiden: NIPG‐TNO 1994

- 2.Fransen M, McConnell S, Bell M. Exercise for osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 20033CD004286 Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Baar M. Effectiveness of exercise therapy in osteoarthritis of hip or knee. Dissertation. 1998

- 4.Veenhof C, Köke A J A, Dekker J, Oostendorp R A, Bijlsma J W J, van Tulder M W.et al Effectiveness of behavioral graded activity in patients with osteoarthritis of hip and/or knee: a randomized clinical trial. Arthritis Rheum 20065925–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Veenhof C, Dekker J, Bijlsma J W, van den Ende C H. Influence of various recruitment strategies on the study population and outcome of a randomized controlled trial involving patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. Arthritis Rheum 200553375–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Altman R, Asch E, Bloch D, Bole G, Borenstein D, Brandt K.et al Development of criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis. Classification of osteoarthritis of the knee. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee of the American Rheumatism Association. Arthritis Rheum 1986291039–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Altman R, Alarcon G, Appelrouth D, Bloch D, Borenstein D, Brandt K.et al The American College of Rheumatology criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis of the hip. Arthritis Rheum 199134505–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fordyce W E, Fowler R S., Jr Lehmann JF, Delateur BJ, Sand PL, Trieschmann RB. Operant conditioning in the treatment of chronic pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 197354399–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lindstrom I, Ohlund C, Eek C, Wallin L, Peterson L E, Fordyce W E.et al The effect of graded activity on patients with subacute low back pain: a randomized prospective clinical study with an operant‐conditioning behavioral approach. Phys Ther 199272279–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vogels E M H M, Hendriks H J M, Van Baar M E, Dekker J, Hopman‐Rock M, Oostendorp R A. Clinical practice guidelines for physical therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. Amersfoort: KNGF 2001

- 11.Bellamy N, Buchanan W W, Goldsmith C H, Campbell J, Stitt L W. Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol 1988151833–1840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bellamy N, Kirwan J, Boers M, Brooks P, Strand V, Tugwell P.et al Recommendations for a core set of outcome measures for future phase III clinical trials in knee, hip, and hand osteoarthritis. Consensus development at OMERACT III. J Rheumatol 199724799–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heijden GJMGvd Shoulder disorder treatment: Efficacy of ultrasoundtherapy and electrotherapy. 1996

- 14.The EuroQol Group EuroQol‐‐a new facility for the measurement of health‐related quality of life. The EuroQol Group. Health Policy 199016199–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oostenbrink J B, Koopmanschap M A, Van Rutten F F H.Handleiding voor kostenonderzoek. Methoden en richtlijnprijzen voor economische evaluaties in de gezondheidszorg. (Handbook for cost studies, methods and guidelines for economic evaluations in health care). The Hague: Health Care Insurance Council, 2000

- 16.Oostenbrink J B, Koopmanschap M A, Rutten F F. Standardisation of costs: the Dutch Manual for Costing in economic evaluations. Pharmacoeconomics 200220443–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Royal Dutch Society for pharmacy Z‐index. G‐standaard. The Hague, The Netherlands: Z‐index, 2002

- 18.Koopmanschap M A, Rutten F F. A practical guide for calculating indirect costs of disease. Pharmacoeconomics 199610460–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Busschbach J J, Brouwer W B, van der D A, Passchier J, Rutten F F. An outline for a cost‐effectiveness analysis of a drug for patients with Alzheimer's disease. Pharmacoeconomics 19981321–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oostenbrink J B, Al M J. The analysis of incomplete cost data due to dropout. Health Econ 200514763–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manca A, Rice N, Sculpher M J, Briggs A H. Assessing generalisability by location in trial‐based cost‐effectiveness analysis: the use of multilevel models. Health Econ 200514471–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.UK Beam Trial Team United Kingdom back pain exercise and manipulation (UK BEAM) randomised trial: effectiveness of physical treatments for back pain in primary care. BMJ 20043291377–1380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barber J A, Thompson S G. Analysis of cost data in randomized trials: an application of the non‐parametric bootstrap. Stat Med 2000193219–3236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Briggs A H, Wonderling D E, Mooney C Z. Pulling cost‐effectiveness analysis up by its bootstraps: a non‐parametric approach to confidence interval estimation. Health Econ 19976327–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thompson S G, Barber J A. How should cost data in pragmatic randomised trials be analysed? BMJ 20003201197–1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pham T, van der H D, Altman R D, Anderson J J, Bellamy N, Hochberg M.et al OMERACT‐OARSI initiative: Osteoarthritis Research Society International set of responder criteria for osteoarthritis clinical trials revisited. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 200412389–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dolan P. Modeling valuations for EuroQol health states. Med Care 1997351095–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matthews J N, Altman D G, Campbell M J, Royston P. Analysis of serial measurements in medical research. BMJ 1990300230–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Richardson G, Manca A. Calculation of quality adjusted life years in the published literature: a review of methodology and transparency. Health Econ 2004131203–1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Briggs A, Fenn P. Confidence intervals or surfaces? Uncertainty on the cost‐effectiveness plane. Health Econ 19987723–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]