Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the efficacy of switching to etanercept treatment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis who already responded to infliximab, but presented side effects.

Methods

Charts of 553 patients with rheumatoid arthritis were retrospectively reviewed to select patients who responded to the treatment with infliximab and switched to etanercept because of occurrence of adverse effects. Clinical data were gathered during 24 weeks of etanercept treatment and for the same period of infliximab treatment before infliximab was stopped. Disease Activity Score computed on 44 joints (DAS‐44), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) 1st hour, Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) of pain, Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ), and C reactive protein (CRP) were assessed every 8 weeks.

Results

37 patients were analysed. Adverse events to infliximab were mostly infusion reactions. No statistically significant difference between infliximab, before withdrawal, and etanercept, after 24 weeks, was detected in terms of DAS‐44 (2.7 and 1.9, respectively), HAQ (0.75 and 0.75, respectively), ESR (21 and 14, respectively) and CRP (0.5 and 0.3, respectively). VAS pain decreased significantly after switching to etanercept treatment (40 and 24, respectively; p<0.05).

Conclusions

Our study shows that etanercept maintains the clinical benefit achieved by infliximab, and suggests that a second tumour necrosis factor (TNF) α inhibitor can be the favourable treatment for rheumatoid arthritis when the first TNFα blocker has been withdrawn because of adverse events.

Tumour necrosis factor (TNF) α blockade is a widely established strategy to treat rheumatoid arthritis. Although TNFα inhibitors share the same target, a different structure and/or mechanism of TNFα antagonism distinguishes each drug.1

A rising concern in treating rheumatoid arthritis is the management of patients who fail to respond to anti‐TNFα therapy. There is growing evidence that lack of efficacy of one TNFα blocking agent does not rule out a better clinical response to another anti‐TNFα.2,3,4,5,6,7,8 In previous studies, however, lack of efficacy was mostly the reason for stopping anti‐TNFα therapy and switching to another TNFα. There are few data8 on the clinical effects of shifting from one TNFα blocking agent to another when the previous drug, despite being effective, has been withdrawn because of the occurrence of adverse reactions—that is, wondering whether the clinical benefit achieved by using an anti‐TNFα drug can be maintained by another anti‐TNFα inhibitor. Our study explored this issue by assessing the clinical response of patients with rheumatoid arthritis who benefited from infliximab and switched to etanercept because of adverse events.

Patients and methods

Patients

Data records of 553 patients with rheumatoid arthritis, fulfilling the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 1987 revised criteria,9 and who have been successfully treated with infliximab, were retrospectively reviewed to select patients who responded to the treatment and switched to etanercept because of the occurrence of adverse events. Patients were identified as eligible for the study according to the following criteria: (1) a Disease Activity Score computed on 44 joints (DAS‐44) of <2.4 or improvement of DAS‐44 according to the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) response criteria10 at the time of switching; (2) infliximab should have been stopped after the period of drug induction, not before 14 weeks; and (3) switching to etanercept. The exclusion criterion was a lack of clinical response to infliximab.

Patients were treated with infliximab at the standard dosage of 3 mg/kg intravenously at 0, 2 and 8 weeks, and every 8 weeks thereafter in association with a disease‐modifying antirheumatic drug (methotrexate) as prescribed by their own rheumatologist. Etanercept was given at a dose of 25 mg twice weekly by subcutaneous injection without changing the current associated disease‐modifying antirheumatic drug.

Study design

This retrospective study was carried out in 12 rheumatology units, in Italy, that participated in A New Traffic Approach Regarding Energy Saving project, a nationwide registry of biological agents endorsed by the National Public Health Service. Ethics committees of all participating centres approved the study after the patients gave written informed consent. Clinical data were gathered during a period of 6 months (24 weeks) of etanercept treatment and for the same period of infliximab treatment before infliximab was stopped. EULAR and ACR response criteria11 were assessed every 8 weeks by evaluating DAS‐44, including Ritchie Articular Index (RAI), swollen joint count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR, mm/1st hour), C reactive protein (CRP, mg/dl) and patient global assessment, and by evaluating tender joint count, physician global assessment, patient Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) of pain and patient Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ).

Statistical analysis

Values are shown as medians with minimum and maximum range. For statistical analysis, the Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare medians. χ2 test was carried out to compare the frequency of categorical data. The significance level was set at p<0.05. No inferential analysis was performed for missing data.

Results

Patients

In all, 37 of 553 patients with rheumatoid arthritis were included in the analysis (table 1). The time elapsed after infliximab was stopped and before switching to etanercept ranged between 2 and 4 weeks. Follow‐up time points before switching are represented as −8, −16 and −24 weeks, and are matched to the same points after switching. It is noteworthy that the design of this study, whereby patients with rheumatoid arthritis with disease remission have been selected, can itself bias the results, and therefore clinical scores may achieve high rates.

Table 1 Demographic and disease characteristics of patients.

| Characteristics | n = 37 |

|---|---|

| Female (%) | 30 (81) |

| Mean (SD) age (years) | 49 (12) |

| Mean (SD) duration of RA (years) | 8.3 (6) |

| Rheumatoid factor positive (%) | 28 (75) |

| Prednisone dosage (mg/day) | 5–12.5 |

| Methotrexate dosage (mg/week) | 10–15 |

| Causes of infliximab discontinuation | |

| Infusion reactions | 35 |

| Poor compliance | 2 |

RA, rheumatoid arthritis.

Clinical efficacy

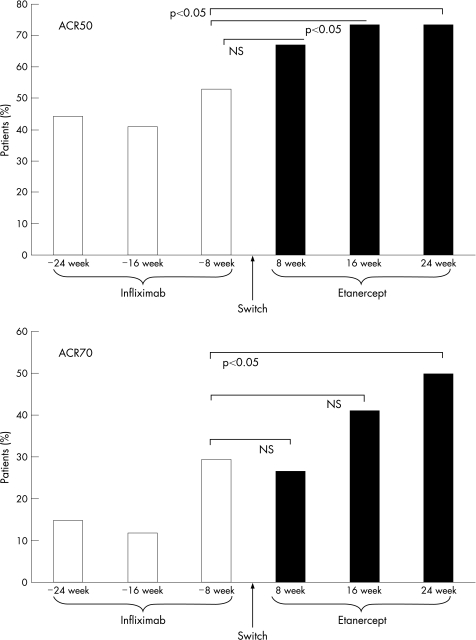

All patients taking infliximab had an improvement of DAS‐44 according to the EULAR response criteria at the time of switching, as defined by the inclusion criteria to the study. As fig 1 shows, the percentage of patients with improvement in ACR50 clinical response progressively increased during infliximab treatment and further augmented after switching to etanercept. The proportion of patients reaching the ACR50 clinical response after taking infliximab at “−8 weeks” was 53%, and although that of the same patients taking etanercept at both 16 and 24 weeks was 73%, the difference was significant (p<0.05). Likewise, the ACR70 criteria response showed a similar profile, and the percentage of patients reaching ACR70 response after “etanercept at 24 weeks” (50%) was significantly higher (p<0.05) than that of “infliximab at −8 weeks” (30%).

Figure 1 Percentage of patients reaching American College of Rheumatology (ACR)50 (upper panel) and ACR70 (lower panel) clinical response criteria during infliximab and etanercept treatment. Infliximab “−24, −16 and −8 weeks” refers to the time of retrospective analysis before drug withdrawal and switching. NS, not significant.

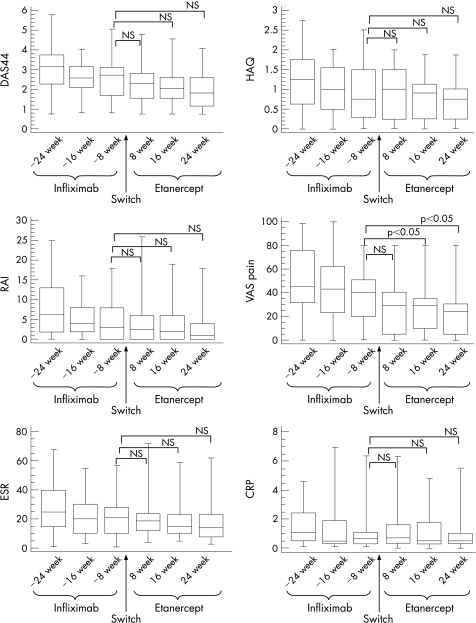

Figure 2 summarises median values with 25th and 75th centiles of DAS44, HAQ, RAI, VAS pain, ESR and CRP. Comparisons between the different etanercept time points and the last infliximab point before switching have been considered. DAS44 joints was 2.7 at “infliximab −8 weeks”, 2.3 at “etanercept 8 weeks”, 2 at “etanercept 16 weeks” and 1.8 at “etanercept 24 weeks”, without statistically significant differences. Similarly, the value of HAQ remained substantially unchanged after “infliximab at −8 weeks” (0.75), “etanercept at 8 weeks” (1), “etanercept at 16 weeks” (0.9) and “etanercept at 24 weeks” (0.75). Also, RAI did not show statistically significant differences when etanercept 8, 16 and 24 weeks were compared with “infliximab at −8 weeks” (2.5, 2, 1.5 and 3, respectively). VAS pain was significantly decreased at “etanercept 8 weeks” (29), at “etanercept 16 weeks” (29) and “etanercept 24 weeks” (24) in comparison to “infliximab at −8 weeks” (40, p<0.05). ESR values were comparable during etanercept treatment (19, 15 and 14 mm/h at 8, 16 and 24 weeks, respectively) and before switching at “infliximab −8 weeks” (21 mm/h). An analogous behaviour was detected for CRP, whose median levels ranged between 0.6 mg/dl at “infliximab −8 weeks” and 0.4 mg/dl at “etanercept 24 weeks”.

Figure 2 Disease Activity Score measured on 44 joints (DAS44), Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ), Ritchie Articular Index (RAI), patient Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) of pain, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR, mm/1st hour) and C reactive protein (CRP, mg/dl) during infliximab and etanercept treatment. Infliximab “−24, −16 and −8 weeks” refers to the time of retrospective analysis before drug withdrawal and switching. Box plots represent the median with 25th and 75th centiles and whiskers 10th and 90th centiles. NS, not significant.

Discussion

The availability of different anti‐TNFα blocking agents with distinct structure, dosing, pharmacokinetics and mechanisms of actions can influence the choice in the strategy of treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis failing to respond to one TNFα blocker can benefit by taking a different TNFα inhibitor. Evaluation of 31 patients with rheumatoid arthritis who received both etanercept and infliximab has shown that switching from etanercept to infliximab, and vice versa, can be effective when the first TNFα antagonist has failed.8 In another study, infliximab induced clinical benefit in 20 patients with rheumatoid arthritis refractory or intolerant to etanercept.6 Likewise, etanercept has been shown to be effective in 25 patients with rheumatoid arthritis who stopped infliximab because of lack of efficacy.5 Recently, switching from infliximab to etanercept has also been shown to be effective in spondyloarthropathies and psoriatic arthritis.2 This would imply that some unknown mechanisms of drug resistance can affect the efficacy of a given biological agent and, more importantly, that despite this resistance the inhibition of TNFα activity may be the strategy to sustain in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis.

Sometimes, an anti‐TNFα drug is withdrawn because of adverse effects despite its efficacy. In this case, it is less known whether switching to another TNFα blocker can still maintain the therapeutic efficacy. van Vollenhoven et al8 showed that etanercept gave similar clinical efficacy after infliximab was discontinued because of side effects in 11 patients with rheumatoid arthritis, and more recently Cohen et al12 provided evidence that 9 patients with rheumatoid arthritis still responded to another TNFα inhibitor after the first one was withdrawn because of intolerance.

In this multicentre retrospective study, we exclusively assessed this issue by evaluating 37 patients with rheumatoid arthritis responding to infliximab, which is the largest cohort studied in the literature to our knowledge, who stopped the treatment because of the occurrence of adverse reactions and began treatment with etanercept. The end point of the study was to assess if etanercept was capable of maintaining the clinical benefit achieved by infliximab. Records of patients with rheumatoid arthritis were reviewed after the period of induction with infliximab treatment and all patients were responsive to infliximab as assessed by DAS‐44 and ACR clinical responses. Data were recorded over the same interval of treatment of 6 months both with infliximab and etanercept. Etanercept was capable of maintaining the clinical benefit achieved by infliximab, and no significant differences in terms of biological indices and clinical outcomes were detected between the best response to infliximab treatment, before withdrawal and etanercept treatment.

The weakness of this study is its retrospective design, and although it cannot be considered a comparison between drugs, it has shown that the efficacy reached by infliximab can be sustained by a second TNFα blocker—namely, etanercept. A further speculation arising from this study is that occurrence of side effects to the first TNFα blocking agent does not predict adverse events to a different anti‐TNFα. Taken together, these data suggest that TNFα targeting strategy can be the favourable treatment to follow in rheumatoid arthritis even when the first TNFα inhibitor has caused the occurrence of adverse events.

Abbreviations

ACR - American College of Rheumatology

CRP - C reactive protein

DAS‐44 - Disease Activity Score computed on 44 joints

ESR - erythrocyte sedimentation rate

EULAR - European League Against Rheumatism

HAQ - Health Assessment Questionnaire

RAI - Ritchie Articular Index

TNF - tumour necrosis factor

VAS - Visual Analogue Scale

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Mpofu S, Fatima F, Moots R J. Anti‐TNF‐alpha therapies: they are all the same (aren't they?). Rheumatology (Oxford) 200544271–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Delaunay C, Farrenq V, Marini‐Portugal A, Cohen J D, Chevalier X, Claudepierre P. Infliximab to etanercept switch in patients with spondyloarthropathies and psoriatic arthritis: preliminary data. J Rheumatol 2005322183–2185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brocq O, Plubel Y, Breuil V, Grisot C, Flory P, Mousnier A.et al Etanercept–infliximab switch in rheumatoid arthritis 14 out of 131 patients treated with anti TNFalpha. Presse Med 2002311836–1839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wick M C, Ernestam S, Lindblad S, Bratt J, Klareskog L, van Vollenhoven R F. Adalimumab (Humira) restores clinical response in patients with secondary loss of efficacy from infliximab (Remicade) or etanercept (Enbrel): results from the STURE registry at Karolinska University Hospital. Scand J Rheumatol 200534353–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haraoui B, Keystone E C, Thorne J C, Pope J E, Chen I, Asare C G.et al Clinical outcomes of patients with rheumatoid arthritis after switching from infliximab to etanercept. J Rheumatol 2004312356–2359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hansen K E, Hildebrand J P, Genovese M C, Cush J J, Patel S, Cooley D A.et al The efficacy of switching from etanercept to infliximab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2004311098–1102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ang H T, Helfgott S. Do the clinical responses and complications following etanercept or infliximab therapy predict similar outcomes with the other tumor necrosis factor‐alpha antagonists in patients with rheumatoid arthritis? J Rheumatol 2003302315–2318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Vollenhoven R, Harju A, Brannemark S, Klareskog L. Treatment with infliximab (Remicade) when etanercept (Enbrel) has failed or vice versa: data from the STURE registry showing that switching tumour necrosis factor alpha blockers can make sense. Ann Rheum Dis 2003621195–1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arnett F C, Edworthy S M, Bloch D A, McShane D J, Fries J F, Cooper N S.et al The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 198831315–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Gestel A M, Prevoo M L, van't Hof M A, van Rijswijk M H, van de Putte L B, van Riel P L. Development and validation of the European League Against Rheumatism response criteria for rheumatoid arthritis. Comparison with the preliminary American College of Rheumatology and the World Health Organization/International League Against Rheumatism Criteria. Arthritis Rheum 19963934–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Felson D T, Anderson J J, Boers M, Bombardier C, Furst D, Goldsmith C.et al American College of Rheumatology. Preliminary definition of improvement in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 199538727–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen G, Courvoisier N, Cohen J D, Zaltni S, Sany J, Combe B. The efficiency of switching from infliximab to etanercept and vice‐versa in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 200523795–800. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]