Abstract

Background

The purpose of the present study is to explore the relation between use of antidepressants and level of alcohol consumption among depressed and nondepressed men and women.

Methods

Random-digit dialling and computer-assisted telephone interviewing were used to survey a sample of 14 063 Canadian residents, aged 18–76 years. The survey included measures of quantity and frequency of drinking, the World Health Organization's Composite International Diagnostic Interview measure of depression, and a question as to whether respondents had used antidepressants during the past year.

Results

Overall, depressed respondents drank more alcohol than did nondepressed respondents. This was not true, however, for depressed men who used antidepressants; they consumed a mean of 414 drinks during the preceding year, versus 579 drinks for depressed men who did not use antidepressants and 436 for nondepressed men. For women, the positive relation between depression and heavier alcohol consumption held true regardless of their use of antidepressants: 264 drinks during the preceding year for depressed women who used antidepressants; 235, for depressed women who did not use antidepressants; and 179, for nondepressed women.

Interpretation

Results of this cross-sectional study are consistent with a possible beneficial effect of antidepressant use upon drinking by depressed men. Further research is needed, however, to assess whether this finding results from drug effects or some other factor, and to ascertain why the effect was found among men but not women.

A positive relation between depression and alcohol consumption has been found,1,2 although the relation does not necessarily apply to all patterns of alcohol consumption3 and may vary by sex.4–6 The association of heavy drinking with depression7 and the evidence that an at least temporarily depressed affect may result from recent, heavy alcohol consumption8 raises the concern that heavy drinking by depressed persons may counteract any beneficial effects of antidepressant medications.9 Moreover, alcohol– drug interactions are possible with some types of antidepressants.10 On the other hand, recent meta-analyses11,12 have suggested a possible beneficial effect of antidepressants on reducing drinking for patients who have combined depressive and substance use disorders, although some research has suggested a stronger effect for men than for women.13 Finally, research distinguishing 2 levels of severity of alcoholism14 has found that SSRIs have no effect or even a negative effect among patients with the more severe type (type B),15–18 but may have a beneficial effect on reducing drinking among those whose alcoholism is less severe (type A).16,17

The purpose of our study was to explore the relation between use of antidepressants and alcohol consumption among depressed and nondepressed men and women in the general population. Several different measures of alcohol consumption were included in the analyses because research has shown that the relation between alcohol consumption and health problems depends on how alcohol consumption is measured (e.g., number of drinks per occasion v. frequency of drinking).19

Methods

The GENACIS Canada survey was developed as part of a large international collaboration (Gender, Alcohol and Culture: an International Study) to investigate the influence of cultural variation on sex differences in alcohol use and related problems. Random-digit dialling was used with computer-assisted telephone interviewing to survey Canadian men and women 18–76 years of age from all 10 provinces, over a 12-month period (starting March 2005 in Quebec and January 2004 in other provinces) to compensate for seasonal variations in alcohol consumption.20 Telephone surveys have been found to be at least as effective as other survey research methods for assessing alcohol use and harms.21,22 They do exclude people who are homeless or living in institutions, those who do not speak English or French, and those who are too cognitively impaired to participate; the numbers in these subpopulations, however, are small. National telephone surveys also tend to underrepresent men, people who have never married and people with some postsecondary education, and overrepresent women, married people and those who obtained a university degree. Otherwise, this method results in a generally representative sample.23 The survey was conducted in English or French, according to the language preference of the respondent.

The telephone surveys, completed by 8055 women and 6012 men (a 53% response rate), took an average of 25 minutes apiece. This response rate is comparable to or better than those obtained in other recent national surveys; for example, the Canadian Addictions Survey,23 conducted by Statistics Canada during roughly the same period, obtained a response rate of 47%.

The interviewers recorded each respondent's sex, year of birth and highest level of education: less than high school; completed high school; some community or technical college; completed community or technical college; some university; completed Bachelor's degree; and postgraduate training (MA, PhD or other professional degree).

Depression was measured using the World Health Organization's Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) measure of depression,24 which has been used in previous Canadian surveys.3 To measure antidepressant use, respondents were asked whether they had taken “antidepressants such as Prozac, Paxil or Effexor” during the past 12 months.

Those who reported that they had consumed alcohol in the past 12 months were asked their usual frequency of drinking, the number of drinks they usually drank on days that they consumed alcohol and the maximum consumed on a single occasion in the past year. Frequency and usual number of drinks were asked separately for wine, beer, spirits and premixed beverages (e.g., “coolers”) as well as for all beverages combined. Standard drink equivalents were provided for each beverage: a 5-ounce (150 mL) serving of wine (12% alcohol), 12 ounces (about 350 mL) of beer (5%), 1.5 ounces (45 mL) of liquor (40%) and 12 ounces of premixed drink (5% alcohol).

The measure for overall frequency of drinking was defined as the highest frequency reported, whether for overall drinking or for a specific beverage. Frequency categories were converted into days per year, as follows: less than once a month (6 d/yr), 1–2 days per week (78 d/yr), 1–3 days per month (24 d/yr), 3–4 days per week (182 d/yr), 5–6 days per week (286 d/yr) and every day (365 d/yr). Annual volumes of alcohol consumed were calculated by multiplying the frequency of drinking each beverage (in days per year) by the usual quantity of that beverage consumed (in drinks per day). Heavy episodic drinking was measured as the frequency of consuming 5 or more drinks in a single day in the past 12 months. Recent drinking was measured as the number of drinks consumed on each day of the week immediately before the survey.

The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT),25 a 10-item measure of hazardous drinking, and other questions on drinking pattern were used to define 4 categories of drinker: abstainer (did not drink in the past 12 mo), low-risk drinker (met Canadian low-risk drinking guidelines),26 hazardous drinker (AUDIT score ≥ 8)27 and moderate (neither a low-risk nor a hazardous) drinker.

Weighting was applied to the data to compensate for design effects (i.e., sampling within households) and some oversampling of smaller provinces that we did to allow regional comparisons. Separate analyses of variance (ANOVA) were used to predict each measure of alcohol consumption (frequency, usual quantity, etc.) based on the dichotomous independent variables of sex, whether the criteria for a diagnosis of major depression were met, and whether antidepressants were taken at any time during the preceding year. Age and education were included as covariates. Analyses were conducted separately for current drinkers (i.e., data from abstainers were excluded) and for all respondents (abstainers scored zero on all alcohol consumption measures). Similar results were found for analyses with and without abstainers; therefore, results are reported only for analyses of current drinkers. Because ANOVA results can be affected by weighting, all analyses were repeated without weighting; these produced essentially the same findings, with slightly stronger effects. (Full results for these analyses can be obtained from the corresponding author, K.G.)

Results

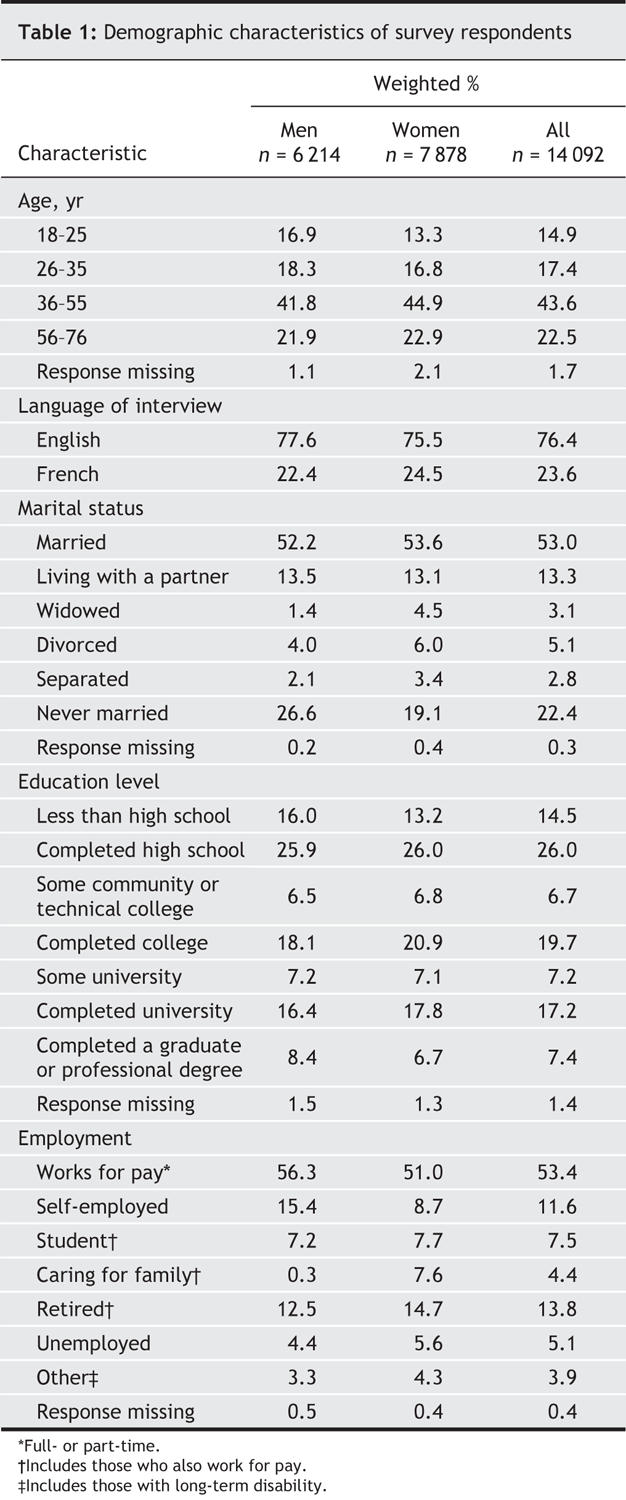

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of respondents (based on weighted data). The largest proportion of respondents was in the 36–55-year age group (mean age for men 42.7 yr, standard deviation [SD] 15.0 yr; mean for women 42.0 yr, SD 14.7 yr). Almost two-thirds were married or living with a partner; a further 19% of the women and 27% of the men never married. Respondents reflected a range of education levels. About 60% of the women and more than 70% of the men were employed or self-employed.

Table 1

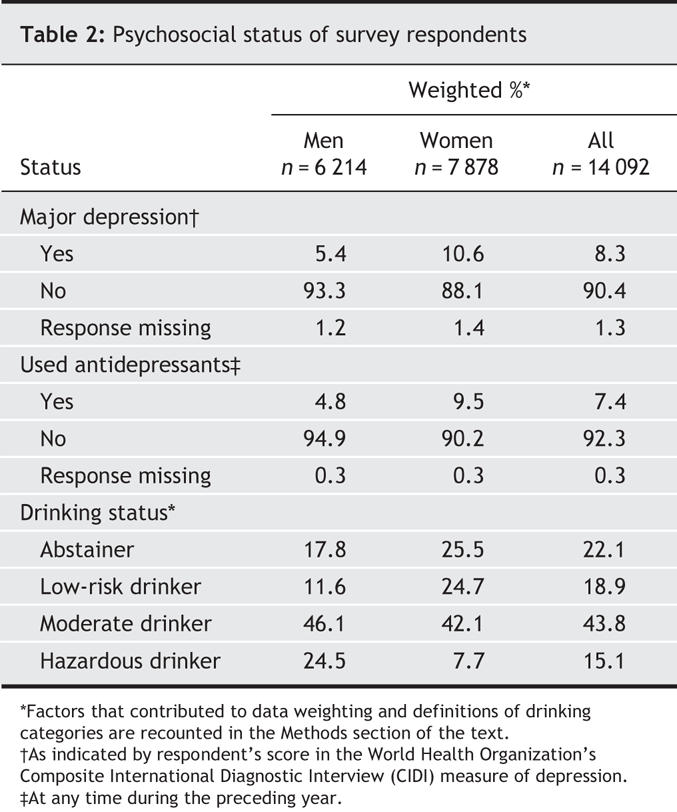

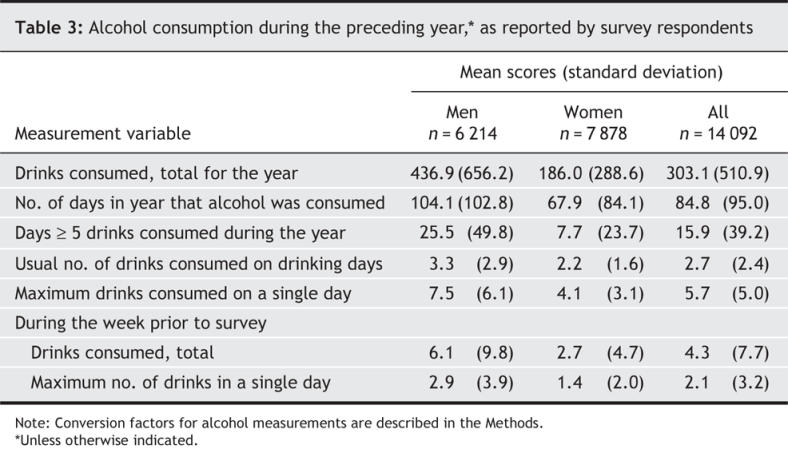

Women were more likely than men to meet the criteria for major depression and to report use of antidepressants (Table 2). Substantially higher use of antidepressants was reported by depressed respondents than by nondepressed respondents (30.7% v. 3.2% for men; 36.6% v. 6.2% for women). Within drinking categories, women were more likely than men to be abstainers or low-risk drinkers, whereas men were more likely to meet criteria for hazardous drinking. Within drinking categories, proportions of respondents who met the criteria for major depression were 5.3% of male and 9.2% of female abstainers; 4.2% and 8.4%, respectively, of low-risk drinkers; 4.5% and 10.9% of moderate drinkers; and 8.1% and 21.7% of hazardous drinkers. The proportions who used antidepressants were 6.8% of male and 9.1% of female abstainers; 4.6% and 9.2% of low-risk drinkers; 3.8% and 9.2% of moderate drinkers; and 5.4% and 13.6% of hazardous drinkers. Among current drinkers, men consumed more alcohol than did women, for all measures of alcohol consumption (Table 2 and Table 3).

Table 2

Table 3

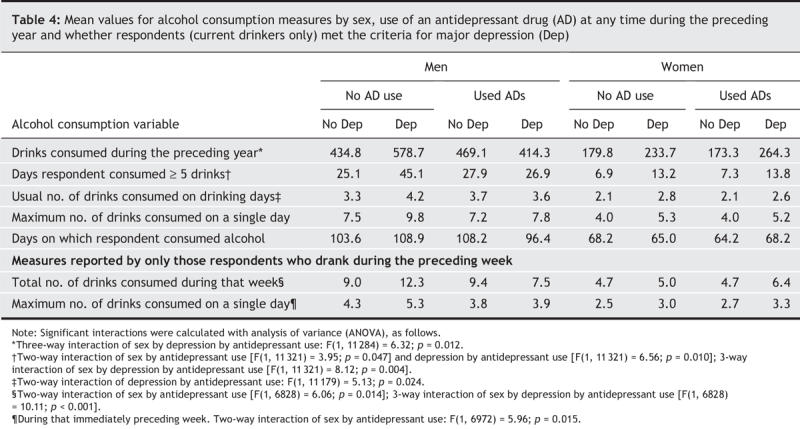

Table 4 shows the average (mean) alcohol consumption for groups defined by sex, use of antidepressants and whether the respondent met diagnostic criteria for major depression. In addition to significant sex differences identified by analyses of variance for all alcohol consumption measures, depressed respondents were found to consume more alcohol than nondepressed respondents when alcohol was measured as total number of drinks consumed in the past year, frequency of consuming 5 or more drinks on an occasion, usual number of drinks on drinking occasions and maximum number of drinks on an occasion in the past year, but not for number of drinking days in the past year or for the 2 measures of the past week's drinking. However, these main effects relating depression and alcohol use need to be interpreted in the context of the significant interactions with sex and use of antidepressants evident in Table 4.

Table 4

Significant 3-way interactions of sex by presence of depression by use of antidepressants were found for 3 measures of alcohol consumption: total number of drinks consumed in the past year, frequency of drinking 5 or more drinks per occasion in the past year and total number of drinks consumed in the past week. There were also several significant 2-way interactions involving sex of respondent, use of antidepressants and depression. As shown by the mean scores on the alcohol consumption measures in Table 4, the 3-way and 2-way interactions reflected the same general pattern: Specifically, for men who did not use antidepressants, being depressed was associated with heavier alcohol consumption; whereas for depressed men who reported using antidepressants during the past 12 months, consumption of alcohol was about the same as that of nondepressed men. For women, however, heavier alcohol use (except for drinking frequency) was associated with depression, regardless of whether the respondent used antidepressants.

Interpretation

Although depressed respondents drank more overall than did nondepressed respondents, depressed men who used antidepressants drank roughly the same amount as nondepressed men and less than depressed men who did not use antidepressants. This finding is consistent with conclusions from previous research13,17,28 that antidepressants may reduce both depressive symptoms and desire for alcohol. Alternatively, the effect may be due to the patient being cautioned about alcohol consumption by his physician at the time that antidepressants were prescribed, consistent with research29 that has shown that advice from a physician can help reduce drinking.

The same pattern was not found for women. Depressed women drank more than nondepressed women, whether they used antidepressants or not. Possibly, the pharmacological effects of antidepressants differ by sex.13 Alternatively, women may be less likely than men to be cautioned by the prescribing physician about drinking, consistent with research30 that has found that primary care physicians are more likely to counsel men than women about hazardous drinking. Even if women and men were cautioned equally, however, research has also found a more consistent effect of physicians on reducing alcohol consumption among problem-drinking male than female patients.31

Our study had several limitations. Respondents were asked about any use of antidepressants over the preceding year; thus, we could not determine the extent of overlap in the use of antidepressants and alcohol, nor the temporal sequence of heavier drinking, depression and use of antidepressants. The survey did not ask about the dosage or type of antidepressant used, and the examples provided, which were of the most commonly used name brands (i.e., Prozac, Paxil or Effexor), did not include all types of antidepressants. This may have resulted in some underreporting of the use of antidepressants that were not listed as examples. Finally, findings related to use of antidepressants by respondents who did not meet diagnostic criteria for depression are difficult to interpret because this use could be associated with a variety of indicators.

These results from a general population sample are consistent with previous clinical research which has suggested that use of antidepressants is associated with lower alcohol consumption among depressed men. That this association was not found for women points to the importance of taking sex into consideration. Further research is needed to address whether the sex differences found in the present study result from the differing nature of depression among men and women, sex differences in responding to antidepressants, or possibly some aspect of the clinical process between the patient and the prescribing physician.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this research was provided through an operations grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Kathryn Graham, primary investigator; Andrée Demers, co–primary investigator; and coinvestigators Louise Nadeau, Jürgen Rehm, Sylvia Kairouz, Colleen Ann Dell, Christiane Poulin, Anne George and Samantha Wells).

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Kathryn Graham is the principal investigator on the larger project, and (along with coinvestigators) was responsible for the overall conception and design of the study. For this paper, she directed the analyses and wrote the first draft of the paper. Agnes Massak conducted the literature search and analyses. Both authors contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript and approved the final version for publication.

We are grateful to Sharon Bernards for her role in data collection and database managment, Samantha Wells for editorial suggestions, and the staff at the Institute for Social Research at York University and Jolicoeur for their assistance in implementing the survey.

This research was conducted as part of the GENACIS project, a collaborative multinational project led by Sharon Wilsnack and affiliated with the Kettil Bruun Society for Social and Epidemiological Research on Alcohol.

Competing interests: None declared.

Correspondence to: Dr. Kathryn Graham, Head, Social Factors and Prevention Interventions, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, 100 Collip Circle, Suite 200, London ON N6G 4X8; fax 519 858-5199; kgraham@uwo.ca

REFERENCES

- 1.Rodgers B, Korten AE, Jorm AF, et al. Risk factors for depression and anxiety in abstainers, moderate drinkers and heavy drinkers. Addiction 2000;95:1833-45. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Lipton R. The relationship between alcohol, stress, and depression in Mexican American and Non-Hispanic Whites. Behav Med 1997;23:101-11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Patten SB, Charney DA. Alcohol consumption and major depression in the Canadian population. Can J Psychiatry 1998;43:502-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Gilman SE, Abraham HD. A longitudinal study of the order of onset of alcohol dependence and major depression. Drug Alcohol Depend 2001;63:277-86. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Grant BF, Harford TC. Comorbidity between DSM-IV alcohol use disorders and major depression: results of a national survey. Drug Alcohol Depend 1995;39:197-206. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Hartka E, Johnstone B, Leino EV, et al. A meta-analysis of depressive symptomatology over time. Br J Addict 1991;86:1283-98. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Caldwell TM, Rodgers B, Jorm AF, et al. Patterns of association between alcohol consumption and symptoms of depression and anxiety in young adults. Addiction 2002;97:583-94. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Virkkunen M, Linnoila M. Serotonin in early-onset alcoholism. Recent Dev Alcohol 1997;13:173-91. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Ramsey SE, Engler PA, Stein MD. Alcohol use among depressed patients: the need for assessment and intervention. Prof Psychol Res Pract 2005;36:203-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Weathermon R, Crabb DW. Alcohol and medication interactions. Alcohol Res Health 1999;23:40-54. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Torrens M, Fonseca F, Mateu G, et al. Efficacy of antidepressants in substance use disorders with and without comorbid depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend 2005;78:1-22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Nunes EV, Levin FR. Treatment of depression in patients with alcohol or other drug dependence, a meta-analysis. JAMA 2004;291:1887-96. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Naranjo CA, Knoke DM. The role of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in reducing alcohol consumption. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62(Suppl 20):18-25. [PubMed]

- 14.Babor TF, Hofmann M, DelBoca FK, et al. Types of alcoholics, I. Evidence for an empirically derived typology based on indicators of vulnerability and severity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992;49:599-608. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Kranzler HR, Burleson JA, Brown J, et al. Fluoxetine treatment seems to reduce the beneficial effects of cognitive-behavioral therapy in Type B alcoholics. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1996;20:1534-41. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Dundon W, Lynch KG, Pettinati HM, et al. Treatment outcomes in Type A and B alcohol dependence 6 months after serontonergic pharmacotherapy. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2004;28:1065-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Pettinati HM, Volpicelli JR, Kranzler HR, et al. Sertraline treatment for alcohol dependence: interactive effects of medication and alcoholic subtype. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2000;24:1041-9. [PubMed]

- 18.Chick J, Aschauer H, Hornik K; Investigators Group. Efficacy of fluvoxamine in preventing relapse in alcohol dependence: a one-year, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicentre study with analysis by typology. Drug Alcohol Depend 2004;74:61-70. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Rehm J, Room R, Monteiro M, et al. Alcohol use. In: Ezzati M, Lopez AD, Rodgers A, Murray CJL (eds.). Comparative quantification of health risks: global and regional burden of disease attributable to selected major risk factors. Geneva: WHO; 2004. p. 959-110.

- 20.Cho YI, Johnson TP, Fendrich M. Monthly variations in self-reports of alcohol consumption. J Stud Alcohol 2001;62:268-72. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.McAuliffe WE, Geller S, LaBrie R, et al. Are telephone surveys suitable for studying substance abuse? Cost, administration, coverage and response rate issues. J Drug Issues 1998;28:455-82.

- 22.Midanik LT., Greenfield TK, Rogers JD. Reports of alcohol-related harm: telephone versus face-to-face interviews. J Stud Alcohol 2001;62:74-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Adlaf EM, Rehm J. Survey design and methodology. In: Adlaf EM, Begin P, Sawka E, editors. Canadian Addiction Survey (CAS). Detailed Report. Ottawa: Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse. 2005. p. 11-19.

- 24.Wittchen H-U, Robins LN, Cottler LB, et al. Cross-cultural feasibility, reliability and sources of variance of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). Br J Psychiatry 1991;159:645-53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, et al. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption–II. Addiction 1993;88:791-804. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Bondy SJ, Rehm J, Ashley MJ, et al. Low-risk drinking guidelines: the scientific evidence. Can J Public Health 1999;90:264-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, et al. AUDIT: The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: guidelines for use in primary care. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001.

- 28.Rosenwasser AM. Alcohol, antidepressants, and circadian rhythms. Human and animal models. Alcohol Res Health 2001;25:126-35. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC. Alcohol screening and brief intervention: dissemination strategies for medical practice and public health. Addiction 2000;95:677-86. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Roeloffs CA, Fink A, Unutzer J, et al. Problematic substance use, depressive symptoms, and gender in primary care. Psychiatr Serv 2001;52:1251-3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Kahan M, Wilson L, Becker L. Effectiveness of physician-based interventions with problem drinkers: a review. CMAJ 1995;152:851-9. [PMC free article] [PubMed]