Abstract

Background

Public health advisories have warned that the use of atypical antipsychotic medications increases the risk of death among elderly patients. We assessed the short-term mortality in a population-based cohort of elderly people in British Columbia who were prescribed conventional and atypical antipsychotic medications.

Methods

We used linked health care utilization data of all BC residents to identify a cohort of people aged 65 years and older who began taking antipsychotic medications between January 1996 and December 2004 and were free of cancer. We compared the 180-day all-cause mortality between residents taking conventional antipsychotic medications and those taking atypical antipsychotic medications.

Results

Of 37 241 elderly people in the study cohort, 12 882 were prescribed a conventional antipsychotic medication and 24 359 an atypical formulation. Within the first 180 days of use, 1822 patients (14.1%) in the conventional drug group died, compared with 2337 (9.6%) in the atypical drug group (mortality ratio 1.47, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.39–1.56). Multivariable adjustment resulted in a 180-day mortality ratio of 1.32 (1.23–1.42). In comparison with risperidone, haloperidol was associated with the greatest increase in mortality (mortality ratio 2.14, 95% CI 1.86–2.45) and loxapine the lowest (mortality ratio 1.29, 95% CI 1.19–1.40). The greatest increase in mortality occurred among people taking higher (above median) doses of conventional antipsychotic medications (mortality ratio 1.67, 95% CI 1.50–1.86) and during the first 40 days after the start of drug therapy (mortality ratio 1.60, 95% CI 1.42–1.80). Results were confirmed in propensity score analyses and instrumental variable estimation, minimizing residual confounding.

Interpretation

Among elderly patients, the risk of death associated with conventional antipsychotic medications is comparable to and possibly greater than the risk of death associated with atypical antipsychotic medications. Until further evidence is available, physicians should consider all antipsychotic medications to be equally risky in elderly patients.

Antipsychotic medications are disproportionately used in elderly populations and have been prescribed to over a quarter of US Medicare beneficiaries in nursing homes.1–3 Reasons for their use include dementia, delirium, psychosis, agitation and affective disorders, but much use is outside approved indications.4 In addition, there have been rapid shifts away from first-generation conventional agents (e.g., chlorpromazine, haloperidol and loxapine) to more actively marketed second-generation atypical agents (e.g., clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine and risperidone).5

In a public health advisory issued on June 15, 2005, Health Canada warned that, compared with placebo, atypical antipsychotic medications increased the risk of death by 60% in a pooled analysis of 17 short-term randomized controlled trials involving elderly patients with dementia.6 Health Canada requested that “all manufacturers of these drugs include a warning and description of this risk in the safety information sheet for each drug.” The advisory did not extend to conventional antipsychotic medications, although the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) noted that this is an important issue to study in the future.7,8

In the absence of data on the risk of death posed by conventional antipsychotic medications, there is mounting concern that clinicians may switch their elderly patients to these older agents,9 particularly since their replacement by the newer drugs occurred so rapidly and recently.5 On the basis of extrapolations mainly from younger populations, some have suggested that the conventional formulations could, in theory, pose risks equal to or greater than those associated with the newer, atypical drugs in elderly populations.10–13 A cohort study involving US Medicare patients eligible for state-funded low-income pharmacy assistance programs showed a 37% increase in the 180-day mortality associated with the use of conventional antipsychotic medications compared with atypical ones.14 However, patients enrolled in state-funded pharmacy assistance programs are not representative of the general elderly population, since on average they have lower incomes and higher morbidity and mortality.

We conducted a population-based cohort study involving all elderly people in British Columbia to compare the short-term mortality between those prescribed a conventional antipsychotic medication and those prescribed an atypical antipsychotic medication. We also examined whether the risk of death differed by dose or duration of drug use and by dementia status and residence in a nursing home.

Methods

We conducted a cohort study involving all British Columbia residents aged 65 years or more who filled a first-recorded (index) prescription for an oral antipsychotic medication between Jan. 1, 1996, and Dec. 31, 2004. To ensure a uniform 1-year eligibility period before filling the index prescription, all study subjects were required to have used at least 1 medical service and have filled at least 1 prescription in the two 6-month intervals before the index date. They could not have used an antipsychotic medication in the year before the index date. We restricted the analysis to include only new users of antipsychotic medications to guard against selection bias among prevalent users from early symptom emergence, drug intolerance or treatment failure.15 Patients with a diagnosis of cancer at the index date were excluded to avoid residual confounding introduced by selective prescribing of conventional antipsychotic medications (chlorpromazine, haloperidol) as antiemetics in the most serious cancer cases, because these patients are also more likely to die within 180 days independent of drug use.

Patients were identified in linked administrative data from the BC Ministry of Health that contained information on all physician services (Medical Services Plan), hospital admissions with up to 25 diagnostic codes and all dispensings of prescription drugs, independent of payor, recorded by the province-wide PharmaNet database. We further linked vital status information from the BC Vital Statistics Agency, the provincial vital statistics bureau. Underreporting and misclassification of data appear to be minimal because of the electronic data entry of all drug dispensings and because hospital diagnoses showed good specificity and completeness.16 Linkage, performed with the use of a personal health number unique to every BC resident, is considered complete among patients using the provincial health care system. All traceable personal identifiers were removed to protect patient confidentiality. The Institutional Review Board of the Brigham and Women's Hospital approved this study, and data-use agreements with the BC Ministry of Health were in place.

Atypical antipsychotic agents17 included in the analyses were risperidone (74.7% of all atypical agents dispensed), quetiapine (14.9%), olanzapine (10.1%) and clozapine (0.3%). Other antipsychotic medications were considered to be conventional17 and included loxapine (69.4% of all conventional antipsychotic drugs dispensed), haloperidol (11.0%), chlorpromazine (7.4%), trifluoperazine (5.0%), thioridazine (3.1%), pimozide (2.4%), promazine (2.4%), perphenazine (1.5%), fluphenazine (0.2%), mesoridazine (0.1%) and thiothixene (< 0.1%). We converted daily doses to chlorpromazine-equivalent milligrams using the midpoints of recommended ranges in geriatric prescribing guidelines.18 We used the median daily dose in the population as a cutoff to assess the effect of higher and lower doses.

The study outcome was death from any cause, as recorded by the BC Vital Statistics Agency. A set of potential confounders was measured based on health care utilization data within 6 months before the initiation of index drug use (index date). These confounders included sociodemographic characteristics (age, sex, race, nursing home residence), generic markers of comorbidity that have shown good validity in predicting death19 (hospital admission for any reason, number of physician visits, number of distinct prescription drugs excluding antipsychotic medications listed earlier and Charlson Comorbidity Index score20), psychiatric morbidity (dementia, delirium, mood disorders, psychotic disorders and other psychiatric disorders), prior use of anticholinergic drugs and current use of anticholinergic drugs. We also identified the presence of conditions that are independent predictors of death and were related to antipsychotic drug use in earlier research, including arrhythmias (defined by the presence of a diagnosis of ventricular or other cardiac arrhythmia plus use of a group I–IV antiarrhythmia medication); diabetes (defined by the presence of a diabetes diagnosis plus use of antidiabetic medications); cerebrovascular disease (both cerebral hemorrhagic and ischemic events); congestive heart failure; acute myocardial infarction (MI); other evidence of ischemic heart disease, including angina (defined as the presence of a diagnosis of angina and nitroglycerin use), percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass graft surgery; and other cardiovascular conditions (valvular disease, aneurysm or peripheral vascular disease).

We performed 3 types of statistical analyses: multivariable Cox regression analysis, propensity score analysis and instrumental variable estimation.

For the multivariable Cox regression analysis, we computed distributions of sociodemographic, clinical and utilization characteristics among the users of conventional and atypical antipsychotic drugs and then calculated the mortality during the first 180 days after initiation of either drug class. We chose a period of 180 days on the basis of the duration of trials in the FDA's repeat analysis (the trials lasted from 4 to 26 weeks, with a modal duration of 10 weeks).6 We constructed unadjusted and multivariable (controlling for calendar year and all covariates listed earlier) Cox proportional hazard models to estimate mortality ratios within 180 days after the start of antipsychotic drug use without censoring, analogous to an intention-to-treat analysis in randomized trials. Models of mortality in the first 39 days, in 40–79 days and in 80–180 days of drug use were also constructed. Adjusted models were run separately in strata defined by dementia and nursing home status. We also investigated whether a dose–response relation existed in adjusted models by separating the conventional drug users into 2 groups: those taking the median daily dose or less and those taking more than the median daily dose.

For the propensity score analysis, we developed Cox regression models adjusted for propensity scores21 for more efficient estimation.22,23 Propensity scores were derived from predicted probabilities estimated in logistic regression models of conventional versus atypical antipsychotic drug use. The final non-parsimonious propensity score model contained all covariates listed earlier and discriminated well between the type of drug used (c statistic = 0.78). Cox regression models of mortality were stratified across tenths of the propensity score.

Finally, we used instrumental variable analysis to provide estimates that would remain unbiased even if important confounding variables were unmeasured.24–26 An instrumental variable is an observable factor related to treatment choice but unrelated to patient characteristics and outcomes. As in other recent work,27 we used as the instrument the prescribing physician's preference for conventional versus atypical antipsychotic medication (as indicated by their most recent new prescription of antipsychotic drug). Using 2-stage linear regression for the instrumental variable estimation and additional adjustment for measured patient characteristics, we calculated the risk difference of 180-day mortality between patients using conventional and those using atypical antipsychotic medications. Linear regression to estimate risk difference is valid in large samples such as ours.28 Because patient-level observations were clustered in physician practices, we performed robust calculations of standard errors of the regression parameters to account for the within-physician correlation of outcomes (Stata statistical software, version 9, StataCorp LP, College Station, Tex.).

Results

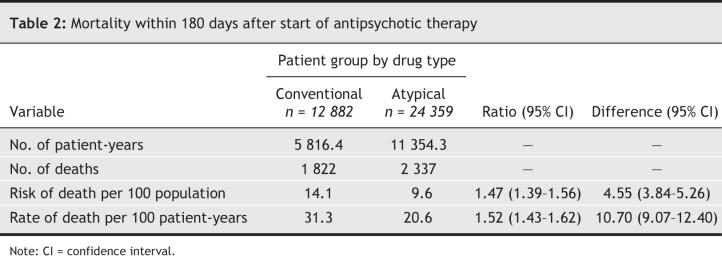

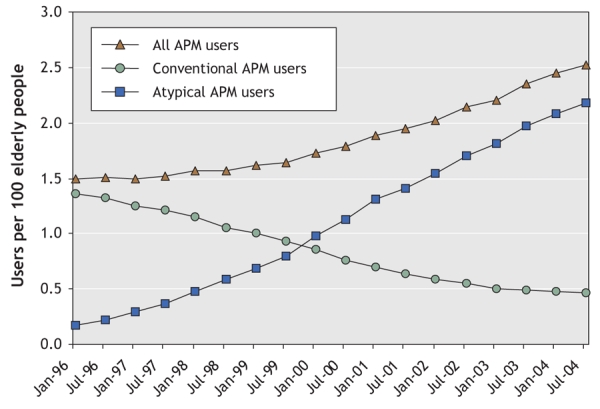

A total of 37 241 elderly people in British Columbia were included in the study cohort; of these, 12 882 were prescribed a conventional antipsychotic medication and 24 359 an atypical formulation. The use of antipsychotic drugs increased during the study period, from 1.5 per 100 seniors to 2.5 per 100 seniors (Fig. 1). The use of atypical antipsychotic medications increased particularly rapidly and exceeded the use of conventional formulations in January 2000. Subjects in the conventional drug group were slightly younger and less likely to be male than those in the atypical drug group (Table 1). Those in the conventional drug group were less likely than those in the atypical drug group to have cerebrovascular disease, diabetes, acute MI, other cardiovascular diseases, dementia, delirium, psychoses, mood disorders and other psychiatric disorders; however, they were more likely to have congestive heart failure and non-MI ischemic heart disease at baseline. Compared with the atypical drug users, the conventional drug users had lower rates of antidepressant use and use of other psychotropic medications, lower total number of drugs, and fewer hospital admissions and nursing home stays.

Fig. 1: Utilization trends of conventional and atypical antipsychotic medications (APMs) among 37 241 elderly people in British Columbia from January 1996 to December 2004.

Table 1

Within the first 180 days of use of antipsychotic medications, the risk of death in the conventional drug group was 14.1%, compared with 9.6% in the atypical drug group (Table 2), for an unadjusted mortality ratio of 1.47 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.39–1.56).

Table 2

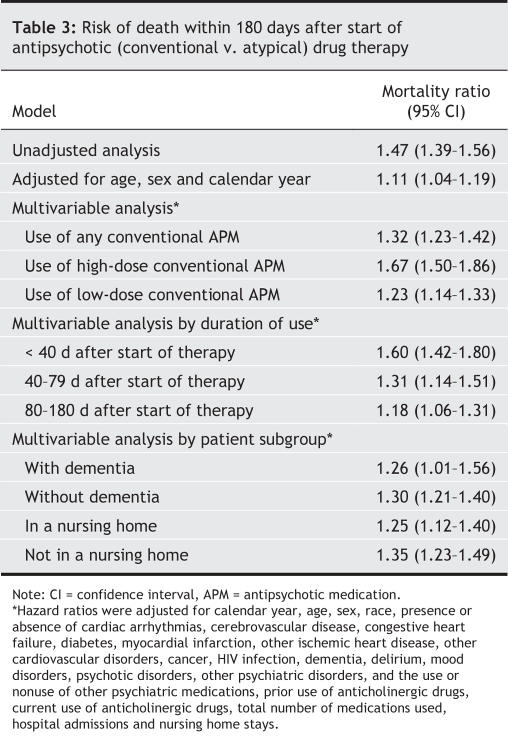

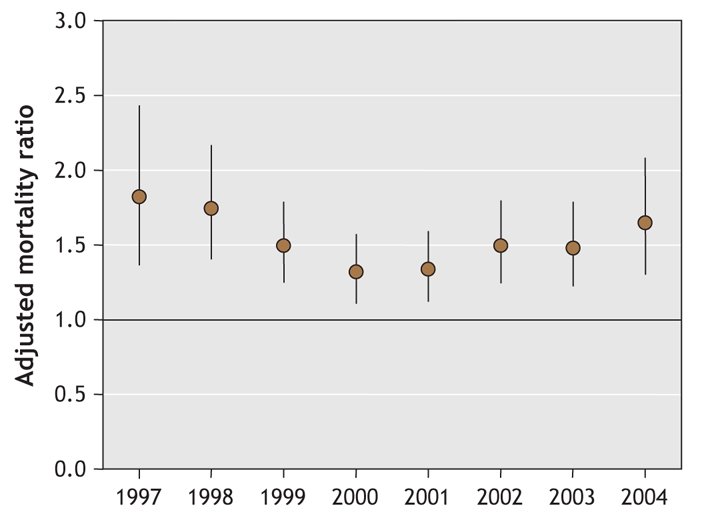

The adjusted mortality ratios comparing the risk of death between the conventional and atypical antipsychotic drug groups are shown in Table 3. Mortality within 180 days was meaningfully increased in the conventional drug group compared with the atypical drug group in multivariable models that controlled for a large number of potential confounders (mortality ratio 1.32). When comparing the most frequently prescribed antipsychotic drugs individually with risperidone, we found increased mortality ratios for haloperidol (2.14, 95% CI 1.86–2.45) and loxapine (1.29, 95% CI 1.19–1.40) but no difference for olanzepine (0.94, 95% CI 0.80–1.09). Yearly adjusted mortality ratios varied little, and in a nonsystematic way, from 1997 to 2004 (Fig. 2). The greatest increase in adjusted mortality risk for conventional versus atypical antipsychotic medications occurred with the use of higher (above median) conventional doses (mortality ratio 1.67) and during the first 40 days after start of therapy (mortality ratio 1.60). In analyses restricted by dementia status or residence in a nursing home, patients in the conventional antipsychotic drug group consistently had a greater 180-day mortality than did patients in the atypical drug group (Table 3). A multivariable analysis of the difference in mortality revealed an estimated increase of 3.5 deaths per 100 population (95% CI 2.7–4.3) in the conventional drug group.

Table 3

Fig. 2: Yearly adjusted mortality ratios comparing the risk of death between the conventional and atypical antipsychotic drug groups, from 1997 to 2004. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Our confirmatory analyses using propensity score adjustments yielded no substantive changes relative to the traditional multivariable Cox regression analyses. For example, the mortality ratio comparing the risk of death within 180 days between the conventional and atypical antipsychotic drug groups after propensity score adjustment was 1.39 (95% CI 1.30–1.49).

In the instrumental variable analyses, use of conventional antipsychotic medications continued to be associated with an increased risk of death within 180 days compared with use of atypical formulations. In these analyses, the adjusted risk difference of 4.2 per 100 (95% CI 1.2–7.3) meant that, for every 100 patients prescribed a conventional antipsychotic drug instead of an atypical drug, there were about 4 additional deaths. The adjusted estimates in the instrumental variable analyses did not differ from the traditional multivariable estimates (p = 0.62). Our instrument was strongly associated with the actual treatment choice (odds ratio 6.1, 95% CI 5.8–6.4).

Sensitivity analyses to rule out possible bias from residual confounding29 revealed that very large relative risks of 5 or more linking a hypothetical confounder to both conventional antipsychotic drug use and mortality would be needed to fully explain the observed increased mortality associated with conventional antipsychotic drug use if no such increase existed.

Interpretation

In our study involving 37 241 elderly residents in British Columbia who began taking antipsychotic therapy during the study period, patients prescribed a conventional agent had a 32% greater, dose-dependent risk of death within 180 days than did those given an atypical agent. To place this magnitude of risk in perspective, all measured health conditions except congestive heart failure and HIV infection conferred smaller adjusted mortality rate ratios in our analyses.

Our results are remarkably close to the increased 180-day mortality associated with conventional antipsychotic drug use observed among US Medicare patients eligible for state-funded low-income pharmacy assistance programs (risk ratio 1.37, 95% CI 1.27–1.49).14 This association was confirmed shortly afterward in a meta-analysis of randomized trials.30 Compared with placebo, the conventional agent haloperidol increased the risk of short-term death by 107% — an estimate higher than that for atypical antipsychotic drugs and remarkably close to the increased risk of 60%–70% associated with atypical drugs versus placebo30 plus the 35% increase in risk associated with conventional drugs observed in our study.

Nonrandomized studies using health care utilization data are particularly scrutinized for their limited control of confounders and their potential for misclassifying diagnoses.31 Confounding would occur if patients who were frail and at increased risk of death were more likely to be prescribed a conventional antipsychotic medication than an atypical formulation. We therefore controlled for calendar year and sociodemographic, clinical and health care utilization factors likely to be independent predictors of death using traditional multivariable analyses as well as propensity score and instrumental variable analysis techniques. Our ability to adjust fully for those factors was limited by their measurement in our database. Random misclassification of confounders leads to incomplete adjustment of confounding bias.32 Model prediction of mortality based on measured covariates in the atypical and conventional antipsychotic user groups indicated nondifferential assessment of patient characteristics. Despite our attempts to control for confounding by indication, it is possible that physicians prescribed haloperidol more frequently than a newer, atypical antipsychotic medication for acute agitation in patients who were more likely to die. It is also possible that patients using atypical antipsychotic medications were physically and cognitively more impaired.

We restricted our study population to new users of antipsychotic medications to control for indications and to ensure that the chronology of use was aligned in both groups and that patient characteristics were measured before drug use and thus not influenced by any treatment effects.15 We further analyzed data as intention-to-treat because of the known potential for drug intolerance or treatment failure that may lead to informative censoring. Such intention-to-treat analyses will likely bias results toward the null.13 During the study period (i.e., before the FDA health advisory7 was posted in 2005), recommendations were published to avoid the prescription of conventional antipsychotic medications to frail elderly patients,4,10–13,33 and any residual confounding may have therefore led to an underestimation of mortality associated with the use of conventional agents.

Finally, we used instrumental variable analysis, which by design can control for unmeasured patient characteristics, and which confirmed our results. Like other statistical approaches, the validity of instrumental variable estimation relies on assumptions. First, the instrument must be related to the actual exposure, which we could demonstrate in our study. Second, an instrument must not be correlated with patient risk factors conditional on measured and adjusted covariates. We found that large imbalances of risk factors among the actual treatment groups (Table 1) were substantially reduced in the instrumental variable analysis (data not shown). Although we have shown earlier how methods for instrumental variable estimation perform when using health care utilization databases to study the safety of prescription drug use,34 this does not rule out that some residual confounding persisted.

Non-differential exposure misclassification (e.g., not consuming filled prescriptions or switching classes of antipsychotic medication) and any rare misclassification of British Columbia mortality information would bias results toward the null; differential misclassification (e.g., worse adherence with conventional antipsychotic medication, as has been found35) again may lead to an underestimation of mortality associated with conventional agents. An alternative interpretation untestable in our data is that health care providers may have managed the indication using harsher co-interventions (e.g., physical restraint, sedatives) when conventional therapy failed.

Potential mechanisms through which conventional antipsychotic medications might increase short-term mortality are unknown. In the FDA analysis on which its public health advisory was based, heart-related events (heart failure, sudden death) and infections (mostly pneumonia) accounted for most deaths.6 Anticholinergic properties (affecting blood pressure and heart rate), Q–T prolongation (causing conduction delays) and extrapyramidal symptoms (causing swallowing problems) are at least as common and probably more common with conventional than with atypical antipsychotic agents and should be investigated as potential underlying causes.4,10–13

Together with earlier findings, the results from our study strongly suggest that Health Canada and the FDA should include conventional antipsychotic medications in their public health advisories, which currently warn only of the increased risk of death associated with the use of atypical antipsychotic medications in elderly patients with dementia.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the DEcIDE research network by a contract from the Agency for Health Care Quality and Research to the Brigham and Women's Hospital DEcIDE Research Center (HHSA 29020050016I). Sebastian Schneeweiss was further supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (RO1-AG021950).

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: All authors substantially contributed to the conception, design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting and revising the article for important intellectual content, and gave approval of the final version.

Competing interests: None declared.

Correspondence to: Dr. Sebastian Schneeweiss, Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women's Hospital, 1620 Tremont St., Boston MA 021205, USA; fax 617 232-8602; schneeweiss@post.harvard.edu

REFERENCES

- 1.Colenda CC, Mickus MA, Marcus SC, et al. Comparison of adult and geriatric psychiatric practice patterns: findings from the American Psychiatric Association's Practice Research Network. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2002;10:609-17. [PubMed]

- 2.Giron MS, Forsell Y, Bernsten C, et al. Psychotropic drug use in elderly people with and without dementia. Internal J Geriatr Psychiatry 2001;16:900-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Briesacher BA, Limcangco R, Simoni-Wastila L, et al. The quality of antipsychotic drug prescribing in nursing homes. Arch Intern Med 2005;165:1280-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Alexopoulos GS, Streim J, Carpenter D, et al. Using antipsychotic agents in older patients: Expert Consensus Panel for Using Antipsychotic Drugs in Older Patients. J Clin Psychiatry 2004;65(Suppl 2):5-99. [PubMed]

- 5.Dewa CS, Remington G, Herrmann N, et al. How much are atypical antipsychotic agents being used, and do they reach the populations who need them? A Canadian experience. Clin Ther 2002;24:1466-76. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Health Canada advises consumers about important safety information on atypical antipsychotic drugs and dementia [advisory]. Ottawa: Health Canada; 2005 June 15. Available: www.hc-sc.gc.ca/ahc-asc/media/advisories-avis/2005/2005_63_e.html (accessed 2007 Jan 10).

- 7.Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Deaths with antipsychotics in elderly patients with behavioral disturbances [FDA public health advisory]. Rockville (MD): US Food and Drug Administration; 2005 Apr 11. Available: www.fda.gov/cder/drug/advisory/antipsychotics.htm (accessed 2007 Jan 10).

- 8.Kuehn BM. FDA warns antipsychotic drugs may be risky for elderly. JAMA 2005;293:2462. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Strong C. Antipsychotic use in elderly patients with dementia prompts new FDA warning. Neuropsychiatry Rev 2005;6:1-17.

- 10.Chan YC, Pariser SF, Neufeld G. Atypical antipsychotics in older adults. Pharmacotherapy 1999;19:811-22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Tariot PN. The older patient: the ongoing challenge of efficacy and tolerability. J Clin Psychiatry 1999;60(Suppl. 23):29-33. [PubMed]

- 12.Maixner SM, Mellow AM, Tandon R. The efficacy, safety, and tolerability of antipsychotics in the elderly. J Clin Psychiatry 1999;60(Suppl 8):29-41. [PubMed]

- 13.Lawlor B. Behavioral and psychological symptoms in dementia: the role of atypical antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry 2004;65(Suppl 11):5-10. [PubMed]

- 14.Wang PS, Schneeweiss S, Avorn J, et al. Risk of death in elderly users of conventional vs. atypical antipsychotic medications. N Engl J Med 2005;353:2335-41. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Ray W. Evaluating medication effects outside of clinical trials: new-user designs. Am J Epidemiol 2003;158:915-20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Williams JI, Young W. Inventory of studies on the accuracy of Canadian health administrative databases [pub no 96-03-TR]. Toronto: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences; 1996.

- 17.Katzung BG. Basic and clinical pharmacology. 9th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2003.

- 18.Salzman C, editor. Clinical geriatric psychopharmacology. 4th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2004.

- 19.Schneeweiss S, Seeger J, Maclure M, et al. Performance of comorbidity scores to control for confounding in epidemiologic studies using claims data. Am J Epidemiol 2001;154:854-64. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Romano PS, Roos LL, Jollis JG. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative data: differing perspectives. J Clin Epidemiol 1993;46:1075-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 1983;70:41-55.

- 22.Braitman LE, Rosenbaum PR. Rare outcomes, common treatments: analytic strategies using propensity scores. Ann Intern Med 2002;137:693-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Cepeda MS, Boston R, Farrar JT, et al. Comparison of logistic regression versus propensity score when the number of events is low and there are multiple confounders. Am J Epidemiol 2003;158:280-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Bowden RJ, Turkington DA. Instrumental variables. Cambridge (UK): Cambridge University Press; 1984.

- 25.Angrist JD, Imbens GW, Rubin DB. Identification of causal effects using instrumental variables. J Am Stat Soc 1996;91:444-55.

- 26.McClellan M, McNeil BJ, Newhouse JP. Does more intensive treatment of acute myocardial infarction in the elderly reduce mortality? Analysis using instrumental variables. JAMA 1994;272:859-66. [PubMed]

- 27.Brookhart MA, Wang PS, Solomon DH, et al. Evaluating short-term drug effects using physician-specific prescribing preferences as an instrumental variable. Epidemiol 2006;17:268-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Spiegelman D, Herzmark E. Easy SAS calculations for risk or prevalence ratios and differences. Am J Epidemiol 2005;162:199-200. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Schneeweiss S. Sensitivity analysis and external adjustment for unmeasured confounders in epidemiologic database studies of therapeutics. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2006;15:291-303. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Schneider LS, Dagerman KS, Insel P. Risk of death with atypical antipsychotic drug treatment for dementia: meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. JAMA 2005;294:1934-43. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Schneeweiss S, Avorn J. A review of uses of health care utilization databases for epidemiologic research on therapeutics. J Clin Epidemiol 2005;58:323-37. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Greenland S, Robins J. Confounding and misclassification. Am J Epidemiol 1985;122:495-506. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Barak Y, Shamir E, Weizman R. Would a switch from typical antipsychotics to risperidone be beneficial for elderly schizophrenic patients? A naturalistic, long-term, retrospective, comparative study. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2002;22:115-20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Schneeweiss S, Solomon DH, Wang PS, et al. Simultaneous assessment of short-term gastrointestinal benefits and cardiovascular risks of selective COX-2 inhibitors and non-selective NSAIDs: an instrumental variable analysis. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:3390-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Dolder CR, Lacro JP, Dunn LB, et al. Antipsychotic medication adherence: Is there a difference between typical and atypical agents? Am J Psychiatry 2002;159:103-8. [DOI] [PubMed]