Abstract

Background

The rate of elective primary cesarean delivery continues to rise, owing in part to the widespread perception that the procedure is of little or no risk to healthy women.

Methods

Using the Canadian Institute for Health Information's Discharge Abstract Database, we carried out a retrospective population-based cohort study of all women in Canada (excluding Quebec and Manitoba) who delivered from April 1991 through March 2005. Healthy women who underwent a primary cesarean delivery for breech presentation constituted a surrogate “planned cesarean group” considered to have undergone low-risk elective cesarean delivery, for comparison with an otherwise similar group of women who had planned to deliver vaginally.

Results

The planned cesarean group comprised 46 766 women v. 2 292 420 in the planned vaginal delivery group; overall rates of severe morbidity for the entire 14-year period were 27.3 and 9.0, respectively, per 1000 deliveries. The planned cesarean group had increased postpartum risks of cardiac arrest (adjusted odds ratio [OR] 5.1, 95% confidence interval [CI] 4.1–6.3), wound hematoma (OR 5.1, 95% CI 4.6–5.5), hysterectomy (OR 3.2, 95% CI 2.2–4.8), major puerperal infection (OR 3.0, 95% CI 2.7–3.4), anesthetic complications (OR 2.3, 95% CI 2.0–2.6), venous thromboembolism (OR 2.2, 95% CI 1.5–3.2) and hemorrhage requiring hysterectomy (OR 2.1, 95% CI 1.2–3.8), and stayed in hospital longer (adjusted mean difference 1.47 d, 95% CI 1.46–1.49 d) than those in the planned vaginal delivery group, but a lower risk of hemorrhage requiring blood transfusion (OR 0.4, 95% CI 0.2–0.8). Absolute risk increases in severe maternal morbidity rates were low (e.g., for postpartum cardiac arrest, the increase with planned cesarean delivery was 1.6 per 1000 deliveries, 95% CI 1.2–2.1). The difference in the rate of in-hospital maternal death between the 2 groups was nonsignificant (p = 0.87).

Interpretation

Although the absolute difference is small, the risks of severe maternal morbidity associated with planned cesarean delivery are higher than those associated with planned vaginal delivery. These risks should be considered by women contemplating an elective cesarean delivery and by their physicians.

Cesarean delivery rates in industrialized countries continue to rise.1,2 The rates vary widely by country, health care facility and delivering physician, partly because of differing perceptions by health care providers as well as by pregnant women of its benefits and risks.3–7 The relative safety of cesarean delivery and its perceived advantages relative to vaginal delivery have resulted in a change in the perceived risk–benefit ratio, which has accelerated acceptance.1,4–12 Indeed, a belief has become widespread that the risks of cesarean delivery for healthy women are so low as to make it a reasonable elective option for childbirth.1,4,12–19

Historically, most cesarean deliveries took place because of or in association with obstetrical complications or medical illness. However, rates of elective primary cesarean deliveries with no clear medical or obstetrical indication are rising dramatically.1,5,6,15–20 There is, therefore, a pressing need to assess the risks of maternal complications and death associated with elective cesarean delivery carried out in healthy women. Allen and colleagues18 recently used the Nova Scotia Atlee Perinatal Database to compare outcomes of women whose cesarean deliveries were performed at term without labour and those with planned vaginal deliveries, but the relatively small sample size, the rarity of severe morbidity and absence of maternal deaths resulted in an incomplete picture. The main purpose of our study was to compare the risks of low-risk, elective cesarean delivery with those of planned vaginal delivery among healthy women at term.

Methods

The Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) began collecting information on all admissions to Canada's acute-care hospitals in the early 1980s. CIHI's Discharge Abstract Database has been widely used for perinatal surveillance and research.3,21,22 Data on all deliveries that took place from April 1, 1991 through March 31, 2005 were gathered for study except those occurring in the provinces of Quebec and Manitoba: complete information on these provinces was not contained in the database. The total number of in-hospital deliveries in the study provinces and territories (3 600 398) accounted for about 98% of all deliveries that took place in the study jurisdictions during the 14-year period. Data available from hospital discharge records included sex, age at and date of admission, home postal code, province of residence, date and status at discharge, principal diagnosis, up to 15 secondary diagnoses (coded according to the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9 CM] or the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision, Canada [ICD-10 CA]), and up to 10 diagnostic, therapeutic and surgical procedures (coded according to the Canadian Classification of Diagnostic, Therapeutic, and Surgical Procedures or the Canadian Classification of Health Interventions). All ICD-10 codes used were mapped from the appropriate ICD-9 codes.

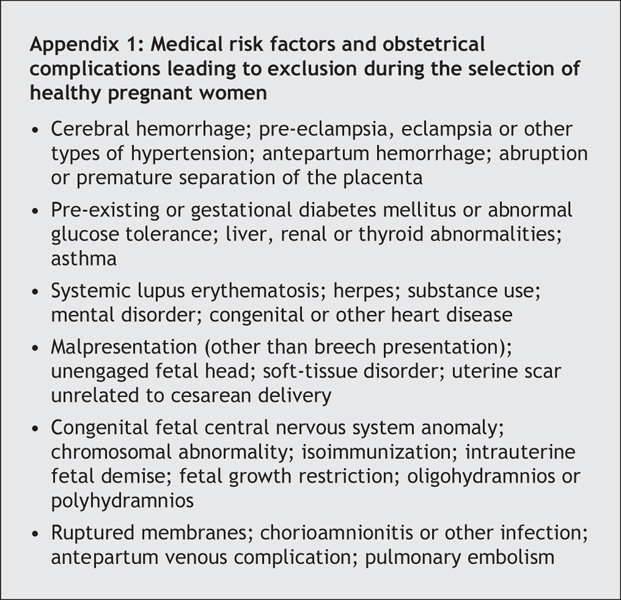

Using information on the index admission, we excluded women with a previous cesarean section, a multiple pregnancy, preterm labour (< 37 completed weeks) or any of the medical risk factors or obstetric complications listed in Appendix 1. The records of a total of 2 339 186 pregnant women remained for inclusion in the study, representing about 65.0% of all original hospital deliveries in the study provinces and territories during the period of investigation.

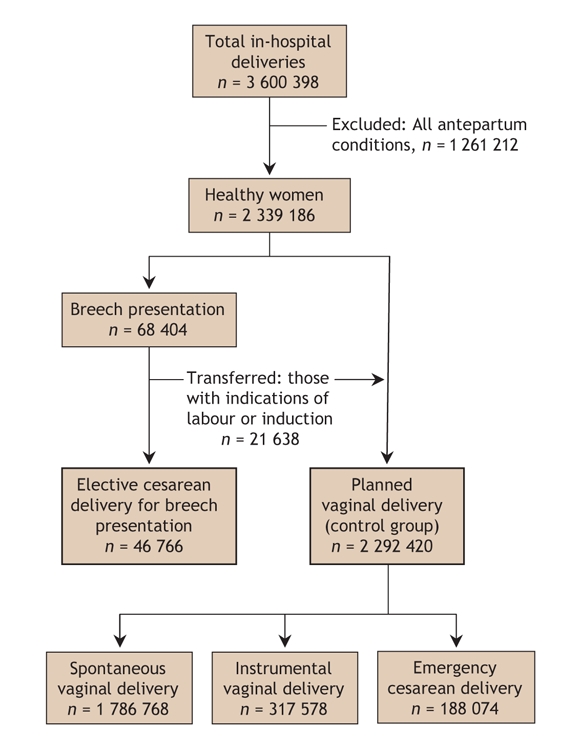

Because no code is available for an elective cesarean section performed “on demand” (i.e., upon maternal request) or without a medical or obstetrical indication, we used cesarean delivery for breech presentation as a surrogate for planned elective low-risk cesarean delivery. We attempted to select only elective primary cesarean deliveries for breech presentation without mention of external cephalic version (ICD-9 CM 652.2) among healthy women as defined above, to whom we refer here as the planned cesarean delivery group. Such elective, low-risk cesarean deliveries should occur in the absence of labour; the Discharge Abstract Database, however, contains no code for labour. We therefore used an algorithm based on the presence of specific ICD-9 CM codes, previously validated with medical charts,23,24 as our criterion to exclude women who experienced labour from this study group. Women with induced labour were also excluded (Fig. 1). The resultant study groups comprised 46 766 women who underwent a planned cesarean delivery for breech presentation and, as the reference group, 2 292 420 healthy women who had a planned vaginal delivery with labour that was either spontaneous or induced.

Fig. 1: Derivation of the comparison groups for the study.

Outcomes of interest included maternal mortality (in-hospital deaths only) and severe morbidity (intra-and postpartum). Severe maternal morbidity was defined as the presence of one or more of the following complications: hemorrhage requiring hysterectomy, hemorrhage requiring blood transfusion, any hysterectomy, uterine rupture, anesthetic complications (including those arising from the administration of a general or local anesthetic, analgesic or other sedation during labour and delivery), obstetric shock, cardiac arrest, acute renal failure, assisted ventilation or intubation, puerperal venous thromboembolism, major puerperal infection, in-hospital wound disruption and hematoma. Length of hospital stay for childbirth was calculated by subtracting the hospital admission date from the discharge date.

We first examined differences in the planned cesarean and planned vaginal delivery groups with respect to the following potential confounding variables: maternal age, year of delivery, province or territory of birth hospital, elderly primigravidity and grand multiparity. Rates of maternal mortality and severe morbidity were compared between the planned cesarean and planned vaginal delivery groups. Adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated via multivariate logistic regression to control for the confounding variables mentioned. Adjusted absolute risk differences (and 95% CIs) in outcome rates were calculated from the absolute outcome rate in the planned vaginal group and adjusted odds ratios in the planned cesarean group. Differences in lengths of hospital stay for childbirth were also examined with multiple linear regression after adjusting for confounding variables.

In the planned vaginal delivery group, labour (whether spontaneous or induced) could lead to any of 3 types of delivery: spontaneous vaginal, instrumental vaginal or unplanned cesarean delivery (Fig. 1). Although we examined outcomes in those 3 subgroups, we did not compare the risks of maternal outcomes between the planned cesarean group and the 3 subgroups of the planned vaginal delivery group because such comparisons are confounded by indication.25

Results

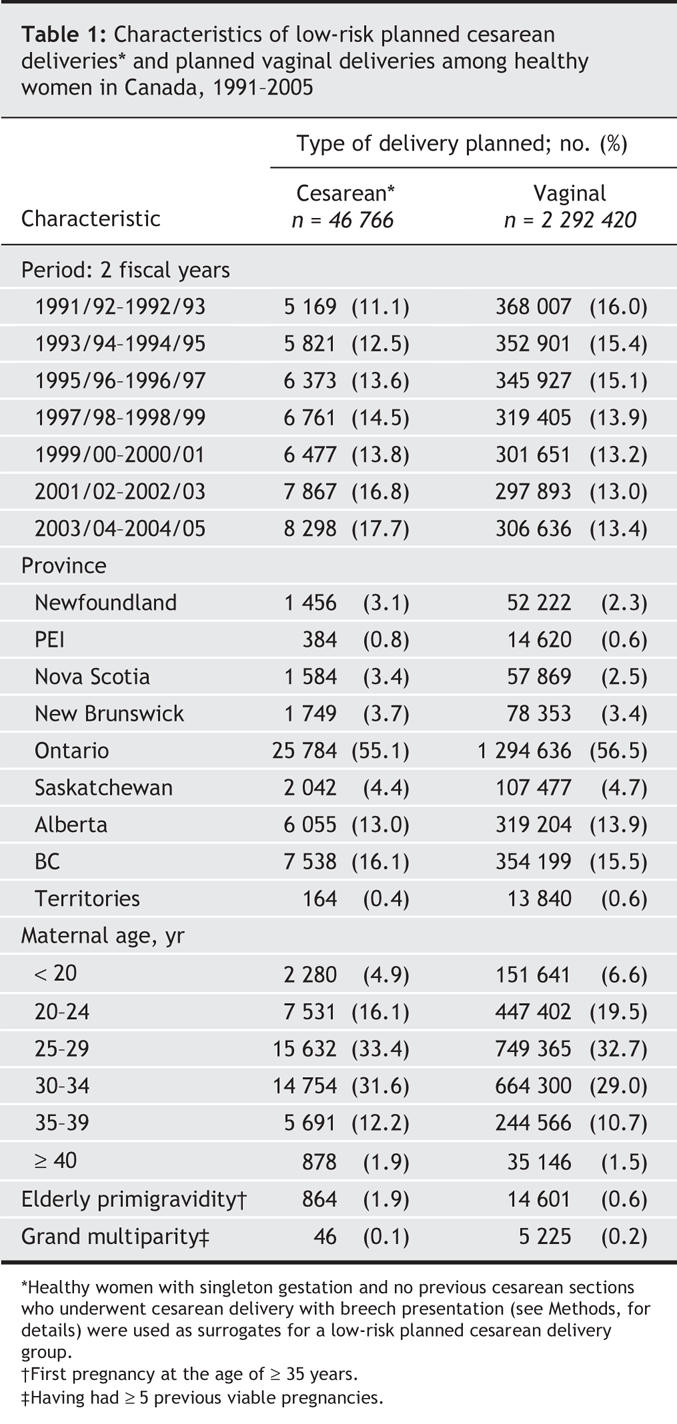

Considerable differences were observed between the planned cesarean and planned vaginal delivery groups, by time period, province or territory of delivery, maternal age, elderly primigravidity and grand multiparity (Table 1).

Table 1

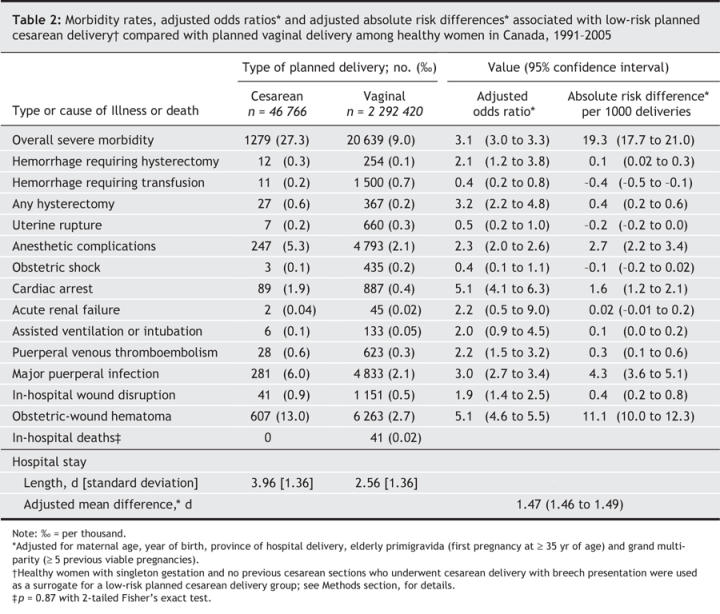

The overall severe maternal morbidity rate was 27.3 per 1000 deliveries (i.e., 27.3) for women in the planned cesarean delivery group, versus 9.0 among those in the planned vaginal delivery group (adjusted odds ratio 3.1; Table 2). The planned cesarean group had an increased risk of most of the complications listed in Table 2, although those for hemorrhage requiring transfusion (odds ratio 0.4, p = 0.005) and uterine rupture (odds ratio 0.5, p = 0.048) were lower than those risks in the planned vaginal delivery group, and that for obstetric shock was slightly lower but nonsignificant (odds ratio 0.4, p = 0.07). No mothers died in-hospital in the planned cesarean delivery group, whereas 41 women died in the planned vaginal delivery group (mortality rate 1.8 per 100 000 deliveries; p = 0.87). The planned low-risk cesarean group had a significantly longer duration of hospital stay (adjusted mean difference 1.47 d, p < 0.001; Table 2).

Table 2

Absolute increases in severe maternal morbidity rates with planned cesarean delivery were low (Table 2). For example, the adjusted absolute risk differences (per 1000 deliveries) were 19.3 for overall severe morbidity, 1.6 for cardiac arrest, 2.7 for anesthetic complications and 4.3 for major puerperal infection.

Among women in the planned vaginal delivery group, those who had a spontaneous vaginal delivery (77.9%) or an instrumental vaginal delivery (13.9%) were less likely to suffer death or serious morbidity, compared with those who delivered by emergency cesarean (8.2%). Women undergoing emergency cesarean delivery had the highest in-hospital maternal mortality rate (9.7 per 100 000 deliveries) and maternal morbidity rates, particularly for cardiac arrest (2.6 per 1000 [2.6]), uterine rupture (2.3), hemorrhage requiring hysterectomy (0.8), hemorrhage requiring transfusion (0.6) and obstetric shock (0.4).

Interpretation

As maternal death has become increasingly rare in Canada and other industrialized countries,4,24,26–29 it is increasingly important to study severe maternal morbidity. We have shown that planned cesarean deliveries are associated with significantly increased risks of specific severe postpartum complications (e.g., hemorrhage requiring hysterectomy, cardiac arrest, venous thromboembolism, major infection) relative to planned vaginal deliveries. Such severe morbidity requires particular clinical attention.4,9–12

The strengths of our study included its population-based provenance, large sample size and detailed information on medical and obstetric conditions. Exclusion criteria based on details of medical and obstetric diagnoses and interventions allowed us to select a group of healthy pregnant women similar to those who might be recruited into a randomized controlled trial.13,30 Data from all selected healthy women were analyzed according to the “intention to treat” principle (planned cesarean delivery group v. planned vaginal delivery group). Our large sample size permitted analysis of rare events such as hysterectomy, cardiac arrest and venous thromboembolism. Healthy women with singleton breech presentation at term who underwent a primary cesarean section should be a reasonably representative surrogate group for women electing cesarean delivery by choice, and thereby help to reduce the confounding by indication that would severely bias a comparison of all cesarean versus vaginal deliveries.13,18,19,24 Although breech presentation carries risks for the infant, for the mother this condition is effectively risk-neutral in terms of the severe maternal morbidity of interest. Thus, the indication for elective cesarean delivery (i.e., breech presentation) would not confound the relationship between cesarean delivery and serious maternal outcomes.

In the United Kingdom, the Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Deaths has shown a significantly higher risk of maternal death associated with cesarean section. However, the Confidential Enquiry recognizes that such findings are clouded by an inability to distinguish deaths associated with underlying maternal diseases from those attributable to the obstetric procedure.27,31 Although the difference we observed in in-hospital maternal deaths between women undergoing planned cesarean versus planned vaginal delivery was not significant, the increased risk of severe morbidity in the planned cesarean group was consistent with previous reports and should better reflect the excess risk due to the procedure itself rather than the clinical indications that led to the procedure.

In general, major puerperal infection is the most common complication of cesarean delivery. The frequency of such infections was increased in association with extended length of labour, rupture of membranes and diabetes mellitus.11,17,32 Our data showed that with planned cesarean delivery, the risk of major infection in women was about 3 times that with planned vaginal delivery. Other factors such as maternal obesity may have confounded this association;33–35 unfortunately, we had no access to height or weight data in this population. Increased risks of other postoperative complications, including those of obstetric wound disruption and hematoma, should be taken into consideration in the evaluation of the risks and benefits of low-risk elective cesarean delivery.

Surprisingly, our data revealed an interesting paradox: planned cesarean delivery was associated with an increased risk of hemorrhage requiring hysterectomy, whereas hemorrhage requiring blood transfusion was more commonly associated with a planned vaginal delivery. Although this paradox might reflect inherent uterine pathology (which is more prevalent in women with breech presentation), such pathology is rare. In our view, the most likely explanation is that the surgical procedure of cesarean delivery increases the likelihood of proceeding to hysterectomy in the face of postpartum hemorrhage, and correspondingly lowers the risk of uterine hemorrhage requiring transfusion.35

Several limitations were inherent to this retrospective cohort study. First, although we endeavoured to select women without labour for the low-risk elective cesarean group by using a validated and published algorithm,23,24 we estimate that 16%–17% of these women might have experienced labour that was not recorded in this database (as estimated by applying this algorithm to the Nova Scotia Atlee Perinatal Database, which contains explicit information on labour).18 Some of these women would have planned cesarean delivery and entered labour before the scheduled cesarean, and then undergone emergency cesarean delivery — a reflection of the real-world situation around planned cesarean delivery. However, some may have been planning a vaginal delivery but underwent emergency cesarean section for obstetric indications that are not coded by the medical records abstractor. Such misclassification of subjects may have biased the results against the planned cesarean delivery group. Second, several important factors (e.g., parity, height, prepregnancy weight and weight gain in pregnancy) that may influence the success of a planned vaginal delivery and the occurrence of complications were unavailable in our database. Finally, our restriction to low-risk women and those without pregnancy complications may have favoured the planned vaginal group somewhat. Ideally, the planned vaginal group should have included women with pregnancy complications if the complication arose after the onset of labour.

A growing number of women request delivery by elective cesarean delivery without an accepted medical indication.20,25 In the absence of high-quality population-based information, physicians are uncertain how to respond or counsel appropriately.36 The occurrence of adverse maternal outcomes in earlier studies may have been due to the clinical indications for cesarean delivery rather than to the procedure itself.26–29,31,33 The best way to avoid confounding by indication would be a randomized controlled trial to evaluate the relative risks and benefits of planned elective cesarean versus planned vaginal delivery — although such a design would certainly raise ethical concerns. One large and potentially relevant randomized clinical trial, the Term Breech Trial,13 found no significant differences in serious maternal complications between policies of planned cesarean delivery and planned vaginal delivery for breech presentation. That study was not large enough to identify differences in the rates of severe morbidity, however. Furthermore, the manipulations of assisted breech delivery and variations in standards of care from centre to participating centre might have had a tendency to bias the results in favour of the cesarean delivery group,37 and would not be generalizable to the majority of deliveries, which take place without breech presentation.

In the absence of adequate and pertinent randomized trials, we must rely on evidence from large observational studies with rigorous attempts to minimize confounding by clinical indications. This article describes an attempt to provide such evidence. Our results suggested that severe maternal morbidity associated with either form of delivery is relatively rare. Nevertheless, compared with planned vaginal delivery at term, elective low-risk cesarean delivery poses higher risks of severe maternal morbidity. Pregnant women and physicians should be aware of these potential risks when contemplating an elective cesarean delivery, and their decisions should be based on the risks and benefits for mother and infant alike.

@ See related article page 475

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the contributions of Leanne Dahlgren (University of British Columbia), William Fraser (University of Montreal), Ling Huang (Public Health Agency of Canada), Robert A. Kinch (McGill University) and Jocelyn Rouleau (Public Health Agency of Canada) to this report.

Appendix 1.

Footnotes

Ethics Board Review: The data used for this study is a denominalized version prepared under strict confidentiality guidelines by the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI), and accessible at the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). Individual consent was not obtained from the patients whose data are contained in the database, and approval from an ethics review board is required by neither CIHI nor PHAC.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Shiliang Liu carried out the study design, statistical analysis and data interpretation, and drafted the manuscript. Robert M. Liston initiated and directed the project, and participated in the interpretation of the data. K.S. Joseph and Maureen Heaman contributed to the study design, data analysis and interpretation, and provided substantial feedback on earlier versions of the manuscript. Reg Sauve and Michael S. Kramer oversaw the study and contributed to the study design, data interpretation and manuscript revision. All authors read, revised and approved the final version for publication.

This study was carried out under the auspices of the Canadian Perinatal Surveillance System. Contributing members of the Maternal Health Study Group include Tom F. Baskett, Sharon Bartholomew, Susie Dzakpasu, Catherine McCourt, Hajnal Molnar-Szakács, Patricia O'Campo, Louise Pelletier, ID Rusen, Shi Wu Wen and David Young.

We are grateful to the Canadian Institute for Health Information for providing us access to the Discharge Abstract Database; Dr. Victoria Allen (Dalhousie University) for her feedback on our exclusion criteria for healthy pregnant women; and John Fahey (Reproductive Care Program of Nova Scotia) for his validation analysis of our “having labour” algorithm. Michael Kramer and Maureen Heaman are career scientists of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). K.S. Joseph is supported by the Peter Lougheed/ CIHR New Investigator award from the CIHR.

Competing interests: None declared.

Correspondence to: Dr. Shiliang Liu, Health Surveillance and Epidemiology Division, Centre for Health Promotion, Public Health Agency of Canada, Jean Mance Building, 200 Eglantine Driveway, AL 1910D, Ottawa ON K1A 0K9; fax 613 941-9927; Shiliang_Liu@phac-aspc.gc.ca

REFERENCES

- 1.National Institutes of Health state-of-the science conference statement: cesarean delivery on maternal request March 27–29, 2006. Obstet Gynecol 2006;107:1386-97. [PubMed]

- 2.Canadian Institute for Health Information. Health indicators, 2005. Available: http://dsp-psd.pwgsc.gc.ca/Collection/H115-16-2005E.pdf (accessed 2006 Nov 20).

- 3.Health Canada. Canadian perinatal health report 2003. Ottawa: Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada; 2003. Available: www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/publicat/cphr-rspc03/pdf/cphr-rspc03_e.pdf (accessed 2006 Nov 20).

- 4.Women's Health Care Physicians, Task Force on Cesarean Delivery Rates. Evaluation of cesarean delivery. Washington: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2000.

- 5.Scott JR. Cesarean delivery on request: Where do we go from here? Obstet Gynecol 2006;107:1222-3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Meikle SF, Steiner CA, Zhang J, et al. A national estimate of the elective primary cesarean delivery rate. Obstet Gynecol 2005;105:751-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Harper V, Hall M. Trends in cesarean section. Curr Probl Obstet Gynecol 1991;1:156-65.

- 8.Stephenson PA, Bakoula C, Hemminiki E, et al. Patterns of use of obstetrical interventions in 12 countries. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 1993;7:45-54. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Hillian EM. Postoperative morbidity following cesarean delivery. J Adv Nurs 1995;22:1035-42. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Petitti DB. Maternal mortality and morbidity in cesarean section. Clin Obstet Gynecol 1985;28:763-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Glazener CM, Abdalla M, Stroud P, et al. Postnatal maternal morbidity: extent, causes, prevention and treatment. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1995;102:282-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Nielsen TF, Hökegård KH. Postoperative cesarean section morbidity: a prospective study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1983;146:911-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Hannah ME, Hannah WJ, Hewson SA, et al; Term Breech Trial Collaborative Group. Planned cesarean section versus planned vaginal birth for breech presentation at term: a randomised multicentre trial. Lancet 2000;356:1375-83. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Webster J. Post-cesarean wound infection: a review of the risk factors. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 1988;28:201-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Parrish KM, Holt VL, Easterling TR, et al. Effect of changes in maternal age, parity, and birth weight distribution on primary cesarean delivery rates. JAMA 1994;271:443-7. [PubMed]

- 16.Hannah ME. Planned elective cesarean section: A reasonable choice for some women? CMAJ 2004;170(5):813-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Surgery and patient choice: the ethics of decision making [ACoG Committee Opinion No. 289]. Obstet Gynecol 2003;102:1101-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Allen VM, O'Connell CM, Liston RM, et al. Maternal morbidity associated with cesarean delivery without labour compared with spontaneous onset of labour at term. Obstet Gynecol 2003;102:477-82. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Heimstad R, Dahloe R, Laache I, et al. Fear of childbirth and history of abuse: implications for pregnancy and delivery. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2006;85:435-40. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Declercq E, Menacker F, MacDorman M. Rise in “no indicated risk” primary caesareans in the United States, 1991–2001: cross sectional analysis. BMJ 2005;330:71-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Wen SW, Liu S, Marcoux S, et al. Uses and limitations of routine hospital admission/ separation records for perinatal surveillance. Chronic Dis Can 1997;18:113-9. [PubMed]

- 22.Liu S, Rusen ID, Joseph KS, et al.; Maternal Health Study Group of the Canadian Perinatal Surveillance System. Recent trends in cesarean delivery rates and indications for caesarean delivery in Canada. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2004;26:735-42. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Gregory KD, Korst LM, Gornbein JA, et al. Using administrative data to identify indications for elective primary cesarean delivery. Health Serv Res 2002;37:1387-401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Henry OA, Gregory KD, Hobel CJ, et al. Using the ICD-9 coding system to identify indications for both primary and repeat cesarean sections. Am J Public Health 1995;85:1143-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Visco AG. Possible pathways for planned vaginal and planned cesarean deliveries. In: NIH State-of-the-Science Conference: Cesarean delivery on maternal request. 2006 Mar 27–29. Bethesda (MD): National Institutes of Health; 2006. p.19-21. Available: http://consensus.nih.gov/2006/CesareanProgramAbstractComplete.pdf (accessed 2006 Nov 20).

- 26.Health Canada. Special report on maternal mortality and severe morbidity in Canada. Enhanced surveillance: the path to prevention. Ottawa: Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada; 2004. Available: www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/rhs-ssg/srmm-rsmm/pdf/mat_mortality_e.pdf (accessed 2006 Nov 20).

- 27.Wen SW, Huang L, Liston R, et al; Maternal Health Study Group of the Canadian Perinatal Surveillance System. Severe maternal morbidity in Canada, 1991–2001. CMAJ 2005;173(7):759-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Liu S, Heaman M, Joseph KS, et al.; Maternal Health Study Group of the Canadian Perinatal Surveillance System. Risk of maternal postpartum readmission associated with mode of delivery. Obstet Gynecol 2005;105:836-42. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.The Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths; Lewis G, editor. Why mothers die 1997–1999: the confidential enquiries into maternal deaths in the United Kingdom. London (UK): RCOG Press; 2001. Available: www.cemd.org.uk/publications.htm (accessed 2007 Jan 5).

- 30.Gilbert WM, Hicks SM, Boe NM, et al. Vaginal versus cesarean delivery for breech presentation in California: a population-based study. Obstet Gynecol 2003; 102: 911-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Lewis G, ed. Why mothers die 2000–2002. The sixth report of confidential enquiries into maternal death in the United Kingdom. London (UK): RCOG Press; 2004. Available: www.cemd.org.uk/publications.htm (accessed 2007 Jan 5).

- 32.Couto RC, Pedrosa TMG, Nogueira JM, et al. Post-discharge surveillance and infection rates in obstetric patients. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 1998;61:227-31. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Joseph KS, Young DC, Dodds L, et al. Changes in maternal characteristics and obstetric practice and recent increases in primary cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol 2003;102:791-800. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Lydon-Rochelle M, Holt VI, Martin DP, et al. Association between method of delivery and maternal rehospitalization. JAMA 2000;283:2411-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Joseph KS, Rouleau J, Kramer MS, et al. Investigation of an increase in postpartum hemorrhage in Canada. Presented at the 19th Annual Meeting of the Society for Pediatric and Perinatal Epidemiologic Research, June 20–21, 2006, Seattle.

- 36.Fernandes JR. Elective cesarean section [letter]. CMAJ 2004;171(1):13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Glezerman M. Five years to the term breech trial: the rise and fall of a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006;194:20-5. [DOI] [PubMed]