Abstract

The mechanisms involved in activation of the transcription factor NF-κB by genotoxic agents are not well understood. Previously, we provided evidence that a regulatory subunit of the IκB kinase (IKK) complex, NF-κB essential modulator (NEMO)/IKKγ, is a component of a nuclear signal that is generated after DNA damage to mediate NF-κB activation. Here, we found that etoposide (VP16) and camptothecin induced increases in intracellular free calcium levels at 60 min after stimulation of CEM T leukemic cells. Inhibition of calcium increases by calcium chelators, BAPTA-AM and EGTA-AM, abrogated NF-κB activation by these agents in several cell types examined. Conversely, thapsigargin and ionomycin attenuated the BAPTA-AM effects and promoted NF-κB activation by the genotoxic stimuli. Analyses of nuclear NEMO levels in VP16-treated cells suggested that calcium was required for nuclear export of NEMO. Inhibition of the nuclear exporter CRM1 by leptomycin B did not interfere with NEMO nuclear export. Similarly, deficiency of a plausible calcium-dependent nuclear export receptor, calreticulin, failed to prevent NF-κB activation by VP16. However, temperature inactivation of the Ran guanine nucleotide exchange factor RCC1 in the tsBN2 cell line harboring a temperature-sensitive mutant of RCC1 blocked NF-κB activation induced by genotoxic stimuli. Overexpression of Ran in this cell model showed that DNA damage stimuli induced formation of a complex between Ran and NEMO, suggesting that RCC1 regulated NF-κB activation through the modulation of RanGTP. Indeed, evidence for VP16-inducible interaction between Ran-GTP and NEMO could be obtained by means of glutathione S-transferase (GST) pull-down assays using GST fused to the Ran binding domain of RanBP2, which specifically interacts with the GTP-bound form of Ran. BAPTA-AM did not alter these interactions, suggesting that calcium is a necessary step beyond the formation of a Ran-GTP-NEMO complex in the nucleus. These results suggest that calcium has a unique role in genotoxic stress-induced NF-κB signaling by regulating nuclear export of NEMO subsequent to the formation of a nuclear export complex composed of Ran-GTP, NEMO, and presumably, an undefined nuclear export receptor.

The Rel/NF-κB family of transcription factors is regulated by a wide variety of extracellular stimuli, including growth factors, cytokines, and gentotoxic anticancer agents (2, 12, 34, 46). The prototypical p50:p65(RelA) heterodimer is expressed in most mammalian cell types examined but kept inactive through the association of its inhibitor protein, such as IκBα. The inactive NF-κB is primarily localized in the cytoplasm, and its activation involves its release from IκBα and translocation to the nucleus. The release of NF-κB from IκBα can be accomplished by different mechanisms, including the well-characterized “canonical” pathway (17, 28, 55). In this pathway, different signaling events lead to the activation of the cytoplasmic IκB kinase (IKK) complex, which mediates site-specific phosphorylation of IκBα. This phosphorylation induces the degradation of IκBα by the ubiquitin-proteasome system and the release of NF-κB for nuclear translocation. In the nucleus, NF-κB binds to cognate decameric κB elements and regulates the transcription of target genes involved in a wide spectrum of processes, including immune and inflammatory responses, proliferation, and apoptosis (2, 12, 81). NF-κB can also influence the development of the cancer phenotype by regulating cell survival, angiogenesis, and metastasis (1, 47).

NF-κB activation is also elicited by genotoxic anticancer agents that cause double-strand breaks in DNA, such as topoisomerase I and II inhibitors and ionizing radiation (IR) (19, 37, 41). NF-κB can induce antiapoptotic genes resulting in a chemo and radio resistance phenotype in cancer (3, 5, 20, 46). Thus, the understanding of the mechanisms important in the regulation of NF-κB activation may provide novel treatment modalities in preventing chemo and radio resistance in certain cancer settings (48). Like the canonical pathway, activation of NF-κB by many genotoxic agents also involves the activation of IKK and the release of NF-κB via IKK activation (40, 52). However, the genotoxic stress-induced pathway appears to involve a distinct series of upstream signaling steps. DNA-damaging agents induce the activation of the nuclear protein kinase ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM), and this appears to be critical for NF-κB activation by double-stranded break inducers (41, 42, 51, 69). Moreover, the nuclear localization of a regulatory subunit of the IKK complex, NF-κB essential modulator (NEMO)/IKKγ, also appears to be a critical event (41). This step of NEMO regulation appears independent of ATM and regulated by posttranslational modification by SUMO-1 (small ubiquitin-like modifier 1). A recent study also suggests that the p53 inducible death domain protein and the receptor-interacting protein 1 participate in regulation of NEMO sumoylation (44). Receptor-interacting protein 1 was also previously implicated in regulation of NF-κB activation via ATM (42). Nuclear NEMO associates with ATM and is further modified by site-specific phosphorylation and ubiquitination to promote export of ATM to the cytoplasm (91). In the cytoplasm, ATM appears to regulate IKK activity in a manner dependent on ELKS, an IKK regulatory subunit previously implicated in cytokine signaling (23). Finally, the p90rsk kinase may also participate in this pathway prior to IKK activation (65).

Multiple stimuli can elicit increases in calcium levels that mediate diverse molecular processes such as transcription, signal transduction, and apoptosis (6, 9, 11). Calcium can also play an important second messenger role for NF-κB activation. The stimulation of calcium-mediated signal transduction pathways regulates NF-κB activation in B cells (21), T cells (22), and neuronal cells (58). In B cells, antigen binding to the B-cell receptor induces the phospholipase C γ2-mediated increase in calcium essential for the protein kinase C β (PKC β) activity required for NF-κB activation (90). Calcium-dependent PKC β phosphorylation of the scaffolding protein CARMA1 then stimulates the IKK activity necessary for NF-κB translocation to the nucleus (79). Interestingly, IR also stimulates increases in intracellular calcium (85) and causes an early (5 min) and a transient increase in the inducible isoform of nitric oxide (NO) synthetase, a calcium/calmodulin-dependent enzyme in Chinese hamster ovary cells (50). This calcium-dependent generation of NO is important for the persistent cell stress signaling initiated by acute IR exposure (60).

In the present study, we examined the role of intracellular calcium in facilitating NF-κB activation by topoisomerase I and II inhibitors, camptothecin (CPT), and etoposide (VP16), respectively. We found that intracellular calcium chelators BAPTA-AM and EGTA-AM inhibited NF-κB activation induced by these genotoxic agents. The effect of BAPTA-AM was partly reversed by the addition of agents that increased intracellular calcium levels, such as thapsigargin and ionomycin. Time course analyses indicated that the critical time period where calcium imparted its NF-κB regulatory activity occurred between 60 and 90 min following CPT or VP16 treatment—the time frame associated with the transition of NEMO into and out of the nucleus. We describe below our molecular analyses that collectively suggest that calcium is critical for NEMO nuclear export via an RCC1-dependent, but CRM1- and calreticulin-independent, mechanism to mediate NF-κB activation in response to CPT and VP16. Thus, our study provides an initial insight into the role of calcium in regulating the NF-κB activation pathway induced by genotoxic stimuli.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and antibodies.

N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM) was acquired from Sigma (St. Louis, MO), while INDO-1, MG132, and cycloheximide were from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA). The antibodies to ATM and CHKII were purchased from Genetech (San Francisco, CA). The phospho-antibodies, ATM (pS1981) and IκBα, were from R& D Systems, Inc., (Minneapolis, MN) and Upstate Biotechnology (Charlottesville, VA), respectively, while the antibody to IκBα was from Santa Cruz (Santa Cruz, CA). The α-tubulin antibody was from Oncogene (San Diego, CA). The generation and culturing of the 1.3E2 murine pre-B cells has been described previously (41).

Cell culture and treatments.

The American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA) supplied the HEK293 and CEM cells. 1.3E2, Myc-NEMO-WT, SUMO-NEMO, and Ub-S85A-NEMO cells were generated previously (41, 91). BHK21 and tsBN2 cells were gifts from James Dahlberg (University of Wisconsin—Madison). The HEK293, BHK21, and tsBN2 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and penicillin/streptomycin (100 μg/ml). CEM cells were cultured in RPMI media with 10% fetal bovine serum and penicillin/streptomycin (100 μg/ml). Unless specified, supplements were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). The HEK293 cells were seeded at 6.5 × 105 cells/six-well dish approximately 18 h before treatment. The CEM cells were also seeded at 5 × 105 cells/ml approximately 18 h prior to treatment. The pH studies used Earle's salt solution (pH 7.2) supplemented with 10% bovine serum, NaHCO3, and l-glutamine. The different pHs were generated by using variations of NaHCO3 and HEPES (10 mM) buffering systems incubated at 37°C in ambient air or 10% CO2. A pH of 6.8 was acquired using HEPES and 10% CO2, a pH of 7.2 was acquired with HEPES/NaHCO3 and 10% CO2, a pH of 7.4 was acquired with NaHCO3 and 10% CO2, and a pH of 8.2 was acquired with NaHCO3 and ambient air incubations. The pH of the media was measured with a pH meter at the termination of the 2-h experiment and is the average of results from two determinations. Transient transfections of plasmid DNA in the HEK293 cells and tsBN2 cells were done according to the method described by Huang et al. (40).

EMSA.

The electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) analysis was done according to the method of Huang et al. (40). The same sample was divided into two separate samples for analysis with the NF-κB (double stranded, 5′-TCA ACA GAG GGG ACT TTC CGA GAG GCC-3′) and Oct-1 (double stranded, 5′-TGT CGA ATG CAA ATC ACT AGA A-3′) radiolabeled probes. Separation of the reaction was preformed on a 4% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel, which was then dried and analyzed with a PhosphorImager (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ).

Western blot analysis.

Western blot analysis was done according to the method of Huang et al. (40). The imaging analysis of Western blots was done by Image J software downloaded from the NIH imaging website.

Calcium analysis.

The calcium analysis used cells (5 × 105/ml) preloaded with INDO-1-AM (2 μM) at 25°C for 30 min in buffer A (25 mM HEPES, 5.4 mM KCl, 0.8 mM MgCl2, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 121 mM NaCl, 5.5 mM glucose, 6 mM NaHCO3, pH 7.3, and 0.5% fetal bovine serum). Cells were isolated and resuspended in buffer A. The cells were placed at room temperature for 20 min to allow de-esterfication of INDO-1-AM. The calcium analysis was carried out at 37°C with flow cytometry (FacsVantage with Diva options; Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Propidium iodide (1 μg/ml) was added to the sample to gate live and dead cells. A 325- to 360-nm wavelength excites the ratiometric INDO-1 fluorophore into emitting light at 405 nm when bound to calcium and at 520 nm when free of calcium (87). To estimate cytoplasmic calcium concentrations, a procedure according to Eastman was incorporated (24). Analysis using digitonin with INDO-1 loading suggested that the calcium ionophore was predominantly in the soluble fraction of the cells. A manganese-stimulated influx with ionomycin demonstrated that the majority of INDO-1-AM was processed to INDO-1 (45). Collectively, the control (dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO] and nontreatment) calcium estimations of 12 different experiments at 3 different time points (30, 60, and 180 min) had a mean of 102 nM ± 18 nM (standard deviation [SD]) and a medium of 106 nM. These values of calcium ranged from a minimum of 77 nM and a maximum at 129 nM. This is within the range of calcium estimated in the controls of nonstimulated cells in the literature (62, 67).

NEMO sumoylation analysis.

Cells resuspended at 2 × 106 cells/ml in fresh media ∼3 h prior to treatment were treated for 1 h with the indicated genotoxic agents. The isolated cells were pelleted (30 × 106 to 60 × 106/sample), washed once with 1× phosphate-buffered saline, then quickly frozen on dry ice, and stored at −70°C until use. Samples were thawed on ice before resuspension in immunoprecipitation (IP) buffer with 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate containing the following protease inhibitors: 8 μM iodoacetamide, 10 μM N-ethylmaleimide, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 2 μM leupeptin, 9.5 TIU/ml aprotinin, 10 mM sodium fluoride, 300 μM sodium orthovanadate. The samples were immediately boiled for 20 min to denature proteins, pelleted at 10,000 rpm for 10 min at room temperature, and diluted 1:10 in immunoprecipitation buffer containing protease inhibitors for a total of 5 ml of reaction mixture. The NEMO antibody (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) was added at 1.5 μg/ml, and samples were tumbled for 1 h at 4°C before the addition of protein G-Sepharose and further incubation overnight. The samples were then pelleted and washed four times in IP buffer. The samples were boiled in 2× sample buffer, run on a polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gel, and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride filter (Millipore, Bedford, MA). SUMO-1/GMP-1 (Zymed Laboratories, San Francisco CA) or NEMO antibodies were used for analysis.

Immunofluorescence analysis.

The staining of the 1.3E2 and Myc-NEMO-WT cells for nuclear localization NEMO was done according to the method of Wu et al. (91). The staining of the BHK21 and tsBN2 cells for p65 was performed similar to that previously described for mouse embryonic fibroblasts (39).

Immuno-pull-down analysis.

The Ran-GTP binding domain of AB1 (RanBP2) (7) was subcloned into a pGST vector to express the glutathione S-transferase (GST)-RanBP fusion protein in Escherichia coli. The carboxy terminus of AB1 not containing the Ran-GTP binding domain was also subcloned into a pGST vector as a negative control. This negative control showed a marked decrease in binding compared to the Ran-GTP binding domain (data not shown). The isolation and GST pull-down assay were done in a manner similar to previous studies (75). Briefly, cells treated for 90 min with VP16 were placed on ice, washed with phosphate-buffered saline, and lysed with buffer B (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.3, 120 mM potassium acetate, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1% Tween 20, and 100 mM of NEM) for 20 min. Dithiothreitol (200 mM) was then added, and the lysate was spun down at 13,000 rpm for 20 min at 4°C. The supernatant was applied at 4°C to a NAP-5 salt-exchange column equilibrated in buffer A (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.3, 120 mM NaCl, 10 mM magnesium acetate, 1 mM dithiothreitol, with phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and aprotinin). Equal concentrations of the eluate were then tumbled with GST-RanBP (7 μg/ml) for 1 h at 4°C after which glutathione beads were applied for 1 h. The beads were pelleted, washed four times in buffer B, and processed for Western blot analysis (see above).

Coimmunoprecipitation assay.

The coimmunoprecipitation studies with transiently expressed hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged Ran-WT and Ran-G19V plasmids in tsBN2 cells used a method described by Wu et al. (91).

Statistical analysis.

The statistical analysis was conducted with Sigma Plot 8.0 and Sigma Stat 3.0 software (SYSTAT Software, Inc., Richmond, CA).

RESULTS

BAPTA-AM blocks NF-κB activation in response to VP16 and CPT.

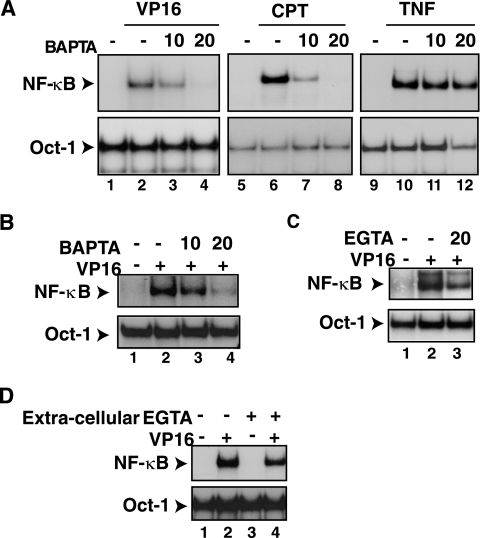

To test whether intracellular calcium is critical for NF-κB activation by genotoxic stimuli, HEK293 human embryonic kidney cells were exposed to the calcium chelator BAPTA-AM 30 min prior to the addition of CPT or VP16 for an additional 2 h. BAPTA-AM effectively blocked NF-κB activation (Fig. 1A, lanes 3, 4, 7, and 8) (P < 0.001) without interfering with its activation by tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) (Fig. 1A, lanes 11 and 12) (not significant [NS]). Western blot analyses indicated that both S32 and S36 phosphorylation induced by IKK and IκBα degradation were inhibited by BAPTA-AM treatment (data not shown). BAPTA-AM also blocked NF-κB activation by CPT, VP16, and IR (data not shown), but not by TNF-α, in CEM human T leukemic cells (Fig. 1B) (P < 0.001). BAPTA-AM similarly abrogated NF-κB activation by CPT, VP16, and IR, but not by lipopolysaccharide, in murine 70Z/3 pre-B cells (data not shown). Moreover, the use of a different intracellular calcium chelator in the same chemical family of BAPTA-AM, EGTA-AM (87), also inhibited the NF-κB activation with VP16 (Fig. 1C) (P < 0.01). In contrast, the removal of extracellular calcium with cell-impermeant EGTA had only a minor effect on NF-κB activation by genotoxin treatment in HEK293 cells (Fig. 1D) (P < 0.05). These results suggested that calcium might have a selective and conserved role in NF-κB activation by the genotoxic stress agents in different cell systems.

FIG. 1.

BAPTA-AM inhibits NF-κB activation by VP16 and CPT. (A) HEK293 cells were exposed to BAPTA-AM (μM) 30 min prior to addition of VP16 (10 μM, 2 h), CPT (10 μM, 2 h) or TNF-α (10 ng/ml, 15 min). Total cell extracts were prepared and analyzed by EMSA using an NF-κB probe (upper panels) or a Oct-1 probe (lower panels). The statistical analysis used analysis of variance for multiple comparisons and Tukey's test for multiple paired analysis. The gels represent results from one of three individual experiments. (B) A similar experiment as in panel A was performed using the CEM T leukemic cell line. (C) A similar experiment as in panel A was performed using the CEM T leukemic cell line with EGTA-AM treatment. (D) HEK293 cells were exposed to EGTA (3 mM) 30 min prior to the addition of VP16 and analyzed as in panel A.

VP16 and CPT induce increases in intracellular calcium levels.

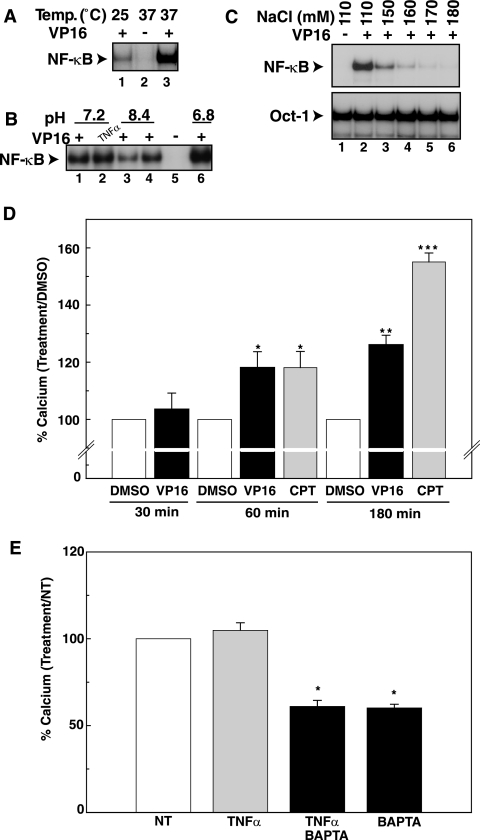

Since BAPTA-AM prevented NF-κB activation by DNA-damaging agents, we next examined whether VP16 and CPT caused increases in intracellular free calcium levels. Generally, calcium measurements are performed in a minimal buffer formulated to maintain the viability of cells in an ambient environment. However, we found that such buffer conditions used for intracellular calcium measurements were not permissive for optimal NF-κB activation in response to genotoxic agents. Cells treated with VP16 at room temperature (∼25°C) displayed reduced NF-κB activation compared to those treated at 37°C (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, the medium pHs of 6.8 and 8.3 increased and decreased, respectively, VP16-dependent activation of NF-κB compared to a normal pH of 7.2 (Fig. 2B). Graded increases in the NaCl concentrations from normal (∼110 mM) to hypertonic concentrations (∼170 mM) in the culture buffer progressively abolished VP16-induced NF-κB activation without interfering with Oct-1 activity (Fig. 2C) (P < 0.001). Surprisingly, an NaCl concentration as low as 130 mM NaCl could attenuate NF-κB activation in CEM T leukemic cells (data not shown). These preliminary studies suggested that NF-κB activation by these genotoxic agents could be highly susceptible to cell culture conditions. Thus, we used a buffer condition with an NaCl concentration (121 mM) in agreement with Bootman and Berridge (13), an incubation temperature of 37°C, and a pH of ∼7.3 for the calcium measurements below to ensure that conditions were conducive for NF-κB activation by genotoxic agents.

FIG. 2.

CPT and VP16 cause significant increases in steady-state calcium levels. (A) HEK293 cells were incubated either at 25°C or 37°C and exposed to VP16 (10 μM, 2 h) and analyzed by EMSA for NF-κB activation. +, present; −, absent. (B) HEK293 cells were incubated in buffers with different pHs as described in Materials and Methods and exposed to VP16 (10 μM) or TNF-α (10 ng/ml) for 2 h for EMSA of NF-κB activation. (C) HEK293 cells were incubated in different salt concentrations and exposed to VP16 (10 μM, 2 h) for EMSA of NF-κB activation. The results were analyzed according to Fig. 1A. (D) CEM cells were preloaded with INDO-1-AM and exposed to the DMSO vehicle control, VP16 (10 μM), or CPT (10 μM) for the indicated times. At the end of each time point, intracellular calcium levels were estimated according to the method described in Materials and Methods. The data from Table 1 are depicted as the percent increase over DMSO-vehicle calcium values at 30, 60, and 180 min with VP16 (10 μM) and/or CPT (10 μM) treatment. The bar graph analysis depicts the estimated steady-state calcium concentrations relative to the DMSO-vehicle values times 100. Each bar is the average ± SD of results from three independent experiments at each time depicted on the graph. (E) CEM cells were preloaded with INDO-1-AM and exposed to TNF-α (10 ng/ml) and other treatments for 15 min. The intracellular calcium levels were estimated as described in Materials and Methods. The data from Table 2 are depicted as the percent increase or decrease over NT calcium values at 15 min with TNF-α (10 ng/ml) and BAPTA-AM (20 μM) treatment. The bar graph analysis depicts the estimated steady-state calcium concentrations relative to the NT values times 100. Each bar is the average ± SD of results from three independent experiments.

To measure intracellular calcium increases, CEM cells were loaded with INDO-1-AM, and the calcium analysis was carried out at 37°C with flow cytometry. A 325- to 360-nm wavelength excites the ratiometric INDO-1 fluorophore into emitting light at 405 nm when bound to calcium and at 520 nm when free of calcium (87). To estimate cytoplasmic calcium concentrations, a procedure according to Eastman (24) was incorporated. Under these conditions, VP16 and CPT treatments demonstrated significant increases in calcium levels compared to the DMSO control at 60 min (P < 0.05) and 180 min (P < 0.05), but not at 30 min (Fig. 2D; Table 1). Thus, steady-state increases in intracellular calcium levels could be observed in these leukemic cells between 60 and 180 min after exposure to these DNA-damaging agents. TNF-α stimulation for 15 min did not increase intracellular calcium levels, consistent with the lack of free calcium for NF-κB activation in this pathway (Fig. 2E; Table 2). BAPTA-AM alone or TNF-α and BAPTA-AM cotreatment reduced calcium below the nontreated (NT) controls.

TABLE 1.

Topoisomerase inhibitors increase calcium levels in CEM cells over timea

| Stimulusb | Time (min) | Estimated [Ca2+] (nM)c | ANOVA [Ca2+] (P value)d | Multiple t test (P value)e |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | 30 | NS | NDf | |

| DMSO | 125 ± 4 | |||

| VP16 | 130 ± 3 | |||

| None | 60 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| DMSO | 82 ± 4 | |||

| VP16 | 96 ± 6 | |||

| CPT | 96 ± 4 | <0.05 | ||

| None | 180 | <0.001 | <0.05 | |

| NT | 97 ± 14 | |||

| DMSO | 105 ± 9 | NS | ||

| VP16 | 132 ± 9 | <0.05 | ||

| CPT | 158 ± 9 | <0.001 |

Cells loaded with INDO-1-AM were exposed to the topoisomerase inhibitors and analyzed by flow cytometry. The intracellular calcium levels were estimated as described in Materials and Methods.

DMSO is the vehicle control for VP16 (10 μM) and CPT (10 μM). The DMSO concentration for treated and vehicle-control determinants was 0.01%. NT indicates the no treatment control.

The estimated calcium concentration is the average of results from three individual experiments ± SD. Each experimental estimate of the calcium concentration was derived from the average of 10,000 events or cells.

The mean calcium concentrations (n = 3) of the different treatment groups were great enough to be statistically significant (P < 0.05) from multiple-comparison analysis of variance (ANOVA).

The individual calcium concentrations were statistically significant from the DMSO or NT values, as determined by Tukey's multiple paired analysis.

ND, not determined.

TABLE 2.

TNF-α treatment does not alter calcium levels in CEM cellsa

| Stimulusb | Estimated [Ca2+] (nM)c | ANOVA [Ca2+] (P value)d | Multiple t test (P value)e |

|---|---|---|---|

| NT | 55 ± 4 | <0.005 | |

| TNF-α | 58 ± 2 | NS | |

| TNF-α + BAPTA | 34 ± 1 | <0.001 | |

| BAPTA | 33 ± 1 | <0.001 |

Cells loaded with INDO-1-AM were exposed to TNF-α and analyzed by flow cytometry. The intracellular calcium levels were estimated as described in Materials and Methods.

NT indicates the no treatment control. TNF-α (10 ng/ml) was added for 15 min. BAPTA-AM (20 μM) was added 10 min prior to the start of the experiment.

The estimated calcium concentration is the average of results from three individual experiments ± SD. Each experimental estimate of the calcium concentration was derived from the average of 10,000 events or cells.

The mean calcium concentrations (n = 3) of the different treatment groups were great enough to be statistically significant (P < 0.01) from multiple-comparison analysis of variance (ANOVA).

The individual calcium concentrations were statistically significant from the NT values as determined by Tukey's multiple paired analysis.

The increase in intracellular calcium is necessary for optimal NF-κB activation.

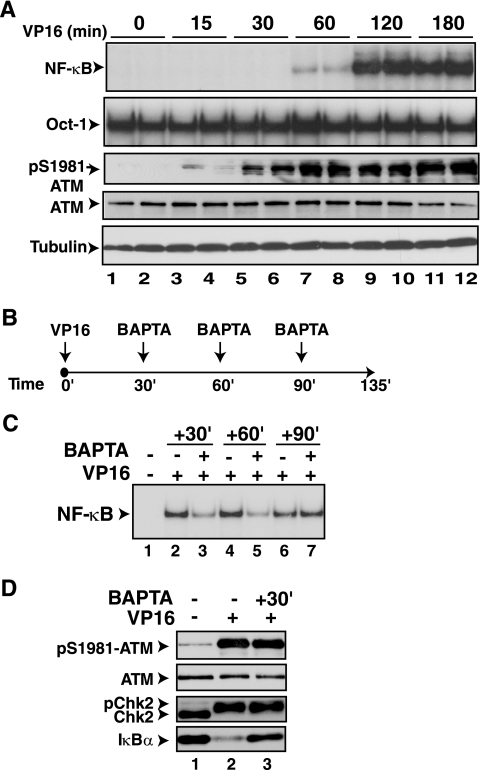

To determine whether the rise in free calcium levels around 60 min after exposure to VP16 is critical for NF-κB activation, we next compared the kinetics of NF-κB activation with that of ATM activation (4) in CEM and HEK293 cells. ATM activation, as measured by the level of phospho-S1981-ATM antibody reactivity (4), reached maximal levels within 15 min of VP16 exposure. In contrast, NF-κB activation as measured by the EMSA in both cell types could only be detectable around 60 min following VP16 exposure but required about 120 min to reach maximal activation (Fig. 3A) (others not shown). Thus, the rise in calcium observed in Fig. 2D appears to occur subsequent to ATM activation and prior to peak NF-κB activation.

FIG. 3.

BAPTA-AM exerts NF-κB inhibitory effects up to 60 min after VP16 exposure. (A) HEK293 cells were exposed to VP16 (10 μM) and processed at the indicated time points in duplicate. The proteins were analyzed by EMSA for NF-κB activation and by Western blot analysis with antibodies to pS1981-ATM, ATM, and α-tubulin. (B) Diagram depicting the treatment protocol used to apply BAPTA-AM after VP16 exposure. (C) HEK293 cells were exposed to VP16 (10 μM) and BAPTA-AM (30 μM) as depicted in panel C and analyzed by EMSA for NF-κB activation. The results were analyzed according to the method described for Fig. 1A. (D) HEK293 cells were exposed to BAPTA-AM (30 μM) 30 min after the addition of VP16 (10 μM) and processed for Western blot analyses with antibodies to pS1981-ATM, ATM, ChK2, and IκBα. The results were quantified by Image J software and analyzed according to the method described for Fig. 1A.

If the calcium rise between 60 and 120 min is critical for NF-κB activation by VP16 treatment, it should be possible to prevent NF-κB activation by adding BAPTA-AM at a point subsequent to ATM activation. To test this idea, we added BAPTA-AM at different times after VP16 addition, as depicted in Fig. 3B, to evaluate the time point at which this calcium chelator causes NF-κB inhibition. Addition of BAPTA-AM significantly reduced NF-κB activation compared to DMSO controls at 30 min (37% ± 7.0%, P < 0.001) and 60 min (47% ± 13%, P < 0.01) after VP16 addition (Fig. 3C). However, BAPTA-AM addition at 90 min after VP16 exposure failed to inhibit NF-κB activation. The inhibition of NF-κB activation with BAPTA-AM addition at 30 min after VP16 treatment did not inhibit ATM activation or the phosphorylation of a substrate of ATM, CHK2 (Fig. 3D) (NS). Thus, BAPTA-AM inhibited NF-κB activation up to 60 min after VP16 exposure subsequent to ATM activation. This time frame correlated with the calcium increase observed at 60 min.

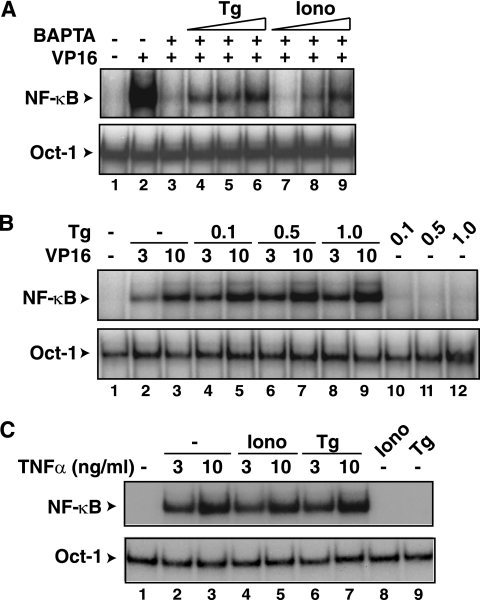

Calcium mobilizers can inhibit the effect of BAPTA-AM.

If increases in intracellular calcium are indeed critical for NF-κB activation by CPT and VP16, it may be possible to reverse the effects of BAPATA-AM by increasing the levels of intracellular calcium by calcium mobilizers, such as thapsigargin or ionomycin. Thapsigargin releases calcium by inhibiting the calcium ATPase pump responsible for maintaining the calcium stores in the endoplasmic reticulum (30, 84). The calcium ionophore ionomycin releases calcium from the extracellular media through the plasma membrane and intracellular stores (30, 70). When HEK293 cells were cotreated with BAPTA-AM and thapsigargin or ionomycin, the BAPTA-AM-dependent inhibition of NF-κB activation was partially reversed by both agents (Fig. 4A). Similarly, ionomycin also reversed the inhibitory effect of BAPTA-AM in CEM cells with CPT treatment (data not shown). Moreover, when HEK293 cells were treated with a suboptimal dose of VP16 (3 μM), thapsigargin was able to increase NF-κB activation in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4B). The thapsigargin-dependent enhancement of NF-κB activation was also observed at the higher concentration of VP16 of 10 μM. Thapsigargin or ionomycin did not affect NF-κB activation by TNF-α (Fig. 4C) nor did treatment alone with these calcium mobilizers activate NF-κB in this cell system (Fig. 4B and C). These observations further supported the role of intracellular calcium in promoting NF-κB activation by genotoxic agents.

FIG. 4.

Thapsigargin and ionomycin reverse the NF-κB inhibitory effects of BAPTA-AM. (A) HEK293 cells treated with VP16 (lane 2) for 2 h were cotreated with BAPTA-AM (30 μM) (lane 3) at 30 min in the absence (−) or presence (+) of increasing amounts of thapsigargin (Tg) at 0.1 μM (lane 4), 0.5 μM (lane 5), or 1.0 μM (lane 6) or ionomycin (Iono) at 0.1 μM (lane 7), 0.5 μM (lane 8), and 1.0 μM (lane 9). DMSO-treated cells (lane 1) were used as controls. The cells were processed for NF-κB activation and the Oct-1 loading control. (B) HEK293 cells were exposed to VP16 (3 or 10 μM) in the absence or presence of increasing amounts of thapsigargin (Tg, μM) for EMSA of NF-κB activation and an Oct-1 loading control. Cells exposed only to thapsigargin were also analyzed in parallel. (C) HEK293 cells were exposed to TNF-α (3 or 10 ng/ml) in the absence or presence of ionomycin (Iono, 1.0 μM) or thapsigargin (Tg, 0.1 μM) for EMSA of NF-κB activation and an Oct-1 loading control. Cells exposed only to ionomycin or thapsigargin were also analyzed in parallel.

Calcium is required for nuclear export of NEMO.

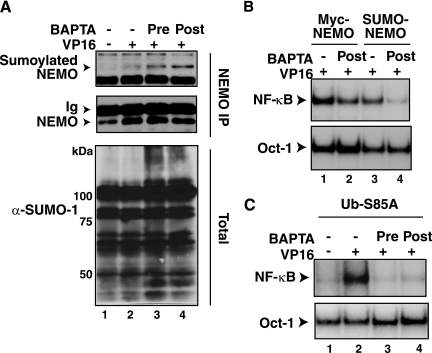

The SUMO-1 modification of NEMO is one of the early molecular events critical for the genotoxic stress-induced NF-κB activation, which occurs around 60 min after VP16 exposure (41, 56). Since this time frame partly overlapped with the rise in intracellular calcium and inhibition of NF-κB activation by BAPTA-AM (Fig. 2 and 3), we next analyzed whether BAPTA-AM treatment inhibited the SUMO-1 modification of NEMO. Total cell extracts prepared from CEM cells exposed to VP16 with or without BAPTA-AM treatment were immunoprecipitated with an anti-NEMO antibody and analyzed by Western blotting using an anti-SUMO-1 antibody. Inducible sumoylation of NEMO was detectable in the VP16 sample (Fig. 5A, lane 2). This sumoylation was not abrogated by BAPTA-AM treatment (lane 3 and 4). General sumoylated protein levels in total cell extracts appeared somewhat increased in the VP16- plus BAPTA-AM-treated samples (lane 3 and lower panel). Consistent with the lack of inhibition of sumoylation of NEMO by BAPTA-AM treatment, VP16-inducible NF-κB activation mediated by the SUMO-NEMO fusion protein expressed in the 1.3E2 NEMO-deficient pre-B cell line (41) was also inhibited by the calcium chelator (Fig. 5B) (P < 0.001). Moreover, NF-κB activation via a Ub-S85A-NEMO fusion protein that could bypass the necessity of ATM-dependent phosphorylation and ubiquitination of NEMO in response to VP16 exposure (91) was also sensitive to inhibition by BAPTA-AM (Fig. 5C) (P < 0.001). These observations suggested that calcium might be necessary for an event downstream of NEMO ubiquitination.

FIG. 5.

BAPTA-AM does not inhibit NEMO sumoylation induced by VP16 and inhibits NF-κB activation mediated by SUMO-NEMO and Ub-S85A-NEMO fusion proteins. (A) CEM cells were treated with VP16 (10 μM) for 1 h with (+) or without (−) BAPTA-AM (30 μM, 30 min) treatment or pretreatment (20 μM) and processed as described in Materials and Methods for NEMO immunoprecipitation and Western blot analysis with anti-SUMO-1 (α-SUMO-1) antibody and anti-NEMO for a control. Total cell extracts were also analyzed by anti-SUMO-1 antibody as an additional control. (B) 1.3E2 NEMO-deficient murine pre-B cells stably reconstituted with Myc-NEMO or SUMO-NEMO proteins were treated with VP16 (10 μM) for 2 h with or without BAPTA-AM (10 μM, 30 min) treatment or pretreatment (20 μM) for EMSA of NF-κB activation and an Oct-1 control. The results were analyzed according to the method described for Fig. 1A. (C) 1.3E2 cells stably reconstituted with Ub-S85A-NEMO protein were treated with VP16 (10 μM) for 2 h with or without BAPTA-AM (10 μM, 30′) treatment or pretreatment for EMSA of NF-κB activation and an Oct-1 control. The results were analyzed according to the method described for Fig. 1A.

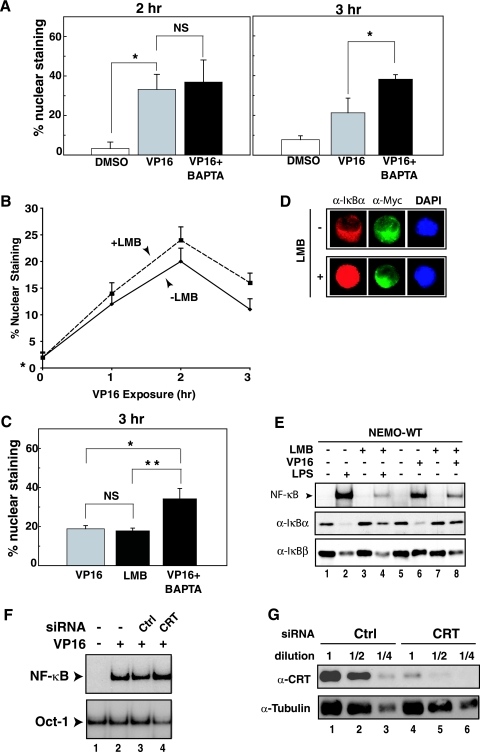

A known event immediately downstream of NEMO ubiquitination is its nuclear export. This is previously observed as a decline in the percentage of cells displaying nuclear staining of NEMO, which was transiently induced by VP16 exposure (91). To determine whether BAPTA-AM prevents the export of NEMO, the subcellular localization of NEMO was monitored in 1.3E2 cells stably reconstituted with Myc-NEMO protein as described previously (91). VP16-inducible increases in NEMO nuclear staining could be observed at up to 2 h when the cells were immobilized on a glass coverslip (Fig. 6A and B). When cells were immobilized in this way, NF-κB activation, as measured by p65 nuclear localization, peaked around 3 h after VP16 treatment, which was about 1 h later than when the same cells were grown in suspension cultures (Fig. 3A and B) (91). The reason for this delay of NF-κB activation of immobilized cells is unknown. Consistent with the lack of defect of sumoylation with BAPTA-AM treatment (Fig. 5A), nuclear accumulation of NEMO in response to VP16 exposure was also unperturbed by BAPTA-AM (Fig. 6A, 2 h). In contrast, at the 3-h time point, BAPTA-AM-treated cells showed more NEMO nuclear staining than the VP16-treated cells (Fig. 6A, 3 h) (P < 0.001). Thus, these results suggested that BAPTA-AM caused either direct or indirect interference on NEMO nuclear export induced by genotoxic stress conditions without preventing its earlier nuclear import process.

FIG. 6.

NEMO nuclear export induced by VP16 treatment is blocked by BAPTA-AM. (A) 1.3E2 cells stably expressing Myc-NEMO were plated on a glass coverslip overnight and then exposed to VP16 (10 μM) for 2 or 3 h, with coexposure to BAPTA-AM (30 μM) given 30 min after VP16 exposure. Cells were fixed and stained with anti-Myc (α-Myc) antibody (9E10) as the primary antibody and fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled secondary anti-mouse antibody to examine nuclear localization of NEMO. 4′,6′-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining was used for nuclear staining. The bar graph represents the average ± SD of results from three independent experiments each at 2 h and 3 h for the percentage of cells displaying nuclear NEMO staining. Each experiment consisted of counting at least 300 individual cells from multiple areas on the slide. Analysis of variance determined that there was a statistically significant difference among the means of the different treatment groups (P < 0.01) at 2 h. The Tukey's multiple paired analysis determined that there was a statistically significant difference between the means of the DMSO-vehicle and VP16 (*, P < 0.05) but not VP16 and VP16 plus BAPTA (NS) at 2 h. Analysis of variance determined that there was a statistically significant difference among the means of the different treatment groups (P < 0.01) at 3 h. The Tukey's multiple paired analysis determined that there was a statistically significant difference between the means of the DMSO-vehicle and VP16 (*, P < 0.05) and VP16 and VP16 plus BAPTA (**, P = 0.01) at 3 h. (B) Similar analysis as in panel A was done at 1, 2, and 3 h after exposure to VP16 with or without LMB (20 ng/ml). (C) Similar analysis as in panel A was done at 3 h after exposure to VP16 with or without LMB (10 ng/ml) or with or without BAPTA (10 μM). Both agents were given 30 min after VP16 exposure. Analysis of variance determined that there was a statistically significant difference among the means of the different treatment groups (P < 0.01) at 3 h. The Tukey's multiple paired analysis determined that there was a statistically significant difference between the means of the DMSO-vehicle and VP16 (*, P < 0.05) and VP16 and VP16 plus BAPTA (**, P = 0.01) at 3 h. (B) Similar analysis as in panel A was done at 1, 2, and 3 h after exposure to VP16 with or without LMB (20 ng/ml). (C) Similar analysis as in panel A was done at 3 h after exposure to VP16 with or without LMB (10 ng/ml) or with or without BAPTA (10 μM). Both agents were given 30 min after VP16 exposure. Analysis of variance determined that there was a statistically significant difference among the means of the different treatment groups (P < 0.01). The Tukey's multiple paired analysis determined that there was a statistically significant difference between the means of the VP16 plus BAPTA and VP16 (*, P < 0.01) and also VP16 plus LMB (**, P < 0.01). However, VP16 and LMB were NS. (D) 1.3E2 cells stably expressing Myc-NEMO were left untreated or exposed to LMB, fixed, and stained with anti-IκBα, anti-Myc, and DAPI to examine the nuclear accumulation of IκBα with LMB treatment. (E) 1.3E2 cells stably expressing Myc-NEMO were left untreated or treated with LMB (20 ng/ml) for 30 min and then exposed to VP16 (10 μM, 2 h) or lipopolysaccharide (10 μg/ml, 30 min). Total cell extracts were then analyzed by EMSA for NF-κB activation and Western blotting with anti-IκBα and anti-IκBβ. (F) HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with siRNA specific to calreticulin (CRT) or control nonspecific siRNA 24 h prior to exposure to VP16 (10 μM, 2 h). Total cell extracts were then analyzed for NF-κB and Oct-1 activities by EMSA. (G) Serial dilutions of total cell extracts prepared from panel F were analyzed for the levels of calreticulin by Western blotting using anticalreticulin antibody. An antitubulin blot was also performed as a loading control.

Nuclear export of NEMO is independent of CRM1 or calreticulin.

Previous studies suggested a critical role for NEMO nuclear export in NF-κB activation by several genotoxic agents (91). However, the mechanism of this nuclear export remains uncharacterized. While we previously showed that activation of IKK by CPT and VP16 was not blocked by leptomycin B (LMB), an inhibitor of the nuclear export receptor CRM1 (41), we did not report the effect of LMB on nuclear export of NEMO. Thus, we tested whether LMB would modulate NEMO export in response to VP16 exposure. Consistent with the lack of IKK inhibition by LMB treatment (41), we failed to observe a marked inhibition of the decline in the percentage of cells displaying nuclear staining of NEMO compared to VP16 alone in a 3-h time course study (Fig. 6B). Because the 3-h time point showed a potential difference between the two conditions, we further focused on this time using BAPTA-AM as a control (Fig. 6C). There was no significant difference between the percentage of cells displaying nuclear staining of NEMO between the VP16 and VP16 plus LMB conditions. However, BAPTA-AM-treated cells showed a significantly higher NEMO staining than cells under these conditions (P < 0.01). In these experiments, LMB treatment caused nuclear accumulation of IκBα (Fig. 6D) and prevented its degradation after VP16 exposure (Fig. 6E, lane 8) as described previously (41). In contrast, IκBβ, which does not accumulate in the nucleus with LMB treatment (39, 83), became more susceptible to VP16-inducible degradation (Fig. 6E, compare lanes 6 and 8), possibly due to the lack of competition by IκBα in the cytoplasm for signal-induced degradation. These IκB protein analyses demonstrated that LMB was effectively inhibiting LMB activity under the experimental conditions employed. Thus, these results collectively indicated that NEMO nuclear export induced by genotoxic stress was likely mediated by a CRM1-independent export mechanism.

Since our results found a potential role for calcium in promoting NEMO nuclear export, we next analyzed the role of calreticulin, the only nuclear export receptor that is reported to depend on free calcium for its activity (35, 36). We reduced the expression of calreticulin by small interfering RNA (siRNA) in HEK293 cells. Even though we observed substantial silencing of calreticulin expression, as measured by Western blot analysis (Fig. 6G), NF-κB activation by VP16 was not inhibited (Fig. 6F). Since a small amount of calreticulin that was present in these knockdown cells could fully support NF-κB activation, we next examined NF-κB activation in fibroblasts derived from calreticulin knockout mice (59). However, we did not observe a decrease in NF-κB activation in these cells (data not shown). Thus, like CRM1 above, calreticulin also appeared to be nonessential for NF-κB activation by genotoxic stress conditions.

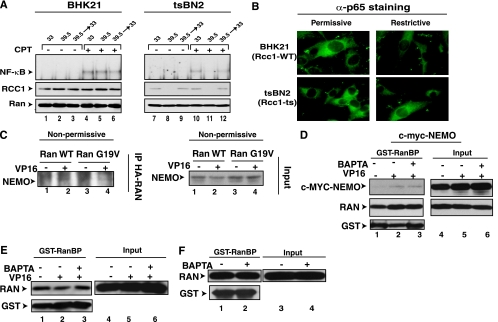

Calcium is required for a nuclear export event downstream of the assembly of the export complex containing Ran-GTP and NEMO.

Many known nuclear export processes are regulated by an energy gradient in the form of Ran-GTP with its greatly higher level in the nucleus than in the cytoplasm (74). The nuclear Ran guanine nucleotide exchange factor RCC1 maintains the high Ran-GTP levels in the nucleus (78). To gain insight into the role of Ran-GTP in promoting NF-κB activation in response to a genotoxic stress condition, we next examined the tsBN2 cell line that is derived from a baby hamster kidney cell line (BHK21) and harbors a temperature-sensitive mutant of RCC1 protein (18). When these cells were grown under the nonpermissive temperature of 39.5°C, RCC1 was degraded over the course of 3 h (Fig. 7A, lanes 8 and 11) (63). When these cells were then treated with CPT (at 33°C), NF-κB activation was inhibited (compare lanes 5 and 11). Returning the cells to the permissive temperature of 33°C for 6 h restored the RCC1 expression before CPT treatment restored NF-κB activation (lane 12). Even though p65 can be a nucleocytoplasmic shuttling protein (32, 38, 57, 82), incubation of tsBN2 cells in the nonpermissive condition for 3 h did not alter the cytoplasmic p65 localization (Fig. 7B). This demonstrated that the lack of NF-κB activation under the nonpermissive condition was not due to mislocalization of inactive p65 protein to the nucleus.

FIG. 7.

Calcium is required for a nuclear export event downstream of the assembly of the export complex containing Ran-GTP and NEMO. (A) BHK21 and tsBN2 cells were incubated at permissive (33°C) or nonpermissive (39.5°C) temperature for 3 h to cause RCC1 degradation and then exposed to CPT (10 μM, 2 h) at 33°C. Cells in lanes 3, 6, 9, and 12 were first incubated at nonpermissive temperature for 3 h and then returned to the permissive temperature for additional 6 h prior to CPT treatment as above. Total cell extracts were prepared for NF-κB EMSA and Western blotting with anti-RCC1 (α-RCC1) and anti-Ran antibodies. (B) Indicated cells grown at the nonpermissive temperature for 3 h or left in the permissive condition were fixed and stained with anti-p65 antibody. (C) tsBN2 cells were transfected with HA-Ran-WT or HA-Ran-G19V, and these transfected cells were incubated at the nonpermissive temperature for 4 h. Cell extracts were then isolated, and IP assays were performed using anti-HA antibody as described in Materials and Methods. (D) Myc-NEMO was transiently transfected into HEK293 cells, and the cells were left untreated or treated with VP16 for 90 min. BAPTA-AM (30 μM) was also applied 30 min after the addition of VP16. The cell extracts were prepared and the GST pull-down assays were performed using GST-RanBP as described in Materials and Methods. Lanes 1 to 3 show Western blot analysis of indicated proteins after GST pull-down, while lanes 4 to 6 show Western blot analysis of 5% of the input controls. (F) HEK293 cells were treated with BAPTA-AM (20 μM, 120 min). The GST-RanBP pull-down assays were performed as for panel D. (E) HEK293 cells were treated with VP16 (10 μM) for 90 min with BAPTA-AM (30 μM, 30 min). The GST-RanBP pull-down assays were done as described above.

RCC1 regulates nuclear export by loading GTP to Ran to assemble an export complex composed of Ran-GTP, a specific export receptor and the cargo protein (29). To examine if DNA damage conditions could induce the formation of a similar nuclear transport complex containing NEMO, tsBN2 cells were first transiently transfected with HA-tagged wild-type Ran (HA-Ran-WT) and HA-Ran-G19V, a mutated Ran (G19V) with diminished GTPase activity, and then stimulated with VP16 at nonpermissive temperature, and coimmunoprecipitation experiments were performed with extracts derived from these treated cells. Exogenous Ran was transfected to increase the cellular levels of Ran-GTP. Ran-G19V was also employed, since the export function of microinjected Ran-G19V was previously shown to be insensitive to the decrease of RCC1 activities in the tsBN2 cells (54) and thus provides a means to further increase Ran-GTP levels at the nonpermissive condition. A small but reproducible amount of endogenous NEMO was coimmunoprecipitated using anti-HA antibody following VP16 treatment (Fig. 7C). These results suggested that VP16 treatment induced the formation of a complex between Ran and NEMO even in the absence of RCC1 activity. Although endogenous NEMO could be immunoprecipitated with HA-Ran proteins, it was unclear whether NEMO associated with Ran-GTP, a form of Ran that is necessary for nuclear export. A Ran-binding domain (RanBD) from the Ran binding protein 1 or 2 can be employed to assess Ran-GTP levels because the RanBD specifically binds to the GTP-bound form of Ran (7, 75). Moreover, buffers containing high levels (100 mM) of NEM can be used to maximally preserve cellular Ran-GTP levels in a GST pull-down assay, since the cytosolic Ran GTPase-activating protein and nuclear RCC1 activities, both of which are introduced by cell lysis, are blocked by high NEM levels (75). Using this GST pull-down assay, we found evidence that NEMO associated with Ran-GTP in a VP16-inducible manner (Fig. 7D). Significantly, this inducible interaction was not blocked by BAPTA-AM treatment (lane 3). Additionally, the GST pull-down assay demonstrated that BAPTA-AM with or without VP16 treatment did not alter the cellular levels of Ran-GTP (Fig. 7E and F). These results suggested that the inhibitory effect of BAPTA-AM on NEMO nuclear export is unlikely due to RCC1 inhibition but rather due to inhibition of a nuclear export step downstream of the formation of Ran-GTP with a putative NEMO nuclear exporter and NEMO following genotoxic stress induction.

DISCUSSION

Studies of the signaling pathways induced by immune and inflammatory cytokines have provided fundamental insights into the mechanisms of activation of the cytoplasmically localized inactive NF-κB complexes. The consensus has emerged from these studies where the “canonical” NF-κB activation pathway is induced by activation of cytoplasmic IKK complex and degradation of NF-κB-associated inhibitor proteins to release active NF-κB into the nucleus (17). NEMO plays an essential role in this canonical pathway. Similarly, a picture is also emerging in which certain genotoxic stress inducers mediate NF-κB signaling by triggering IKK activation (31, 42, 52, 61, 65, 69). NEMO also plays an essential role in activation of IKK and NF-κB by DNA-damaging agents (41, 44, 91). However, unlike the immune and inflammatory modulators, where NEMO remains in the cytoplasm and may be modified by unconventional K63-linked polyubiquitination (17), a small amount of free NEMO appears to leave the cytoplasm either constitutively (44) or in response to DNA damage stimuli to enter the nucleus in association with SUMO-1 modification (41, 91). In the nucleus, NEMO then undergoes a series of modifications to be ultimately exported to the cytoplasm to somehow stimulate IKK activation (91). Thus, one of the important questions to understand the NF-κB signal transduction pathway induced by nuclear DNA damage is: how is the transfer of the DNA damage signal from the nucleus to the cytoplasm regulated? In the present study, our results collectively suggest that nuclear export of NEMO, a component of the nuclear DNA damage signal, in response to genotoxic stress relies on a calcium-dependent process.

Previous studies have demonstrated that exposure of cells to IR can increase free calcium levels (85). In this case, the release of intracellular calcium stores from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) appeared necessary to induce an influx of extracellular calcium, which resulted in a transient increase in free calcium levels within minutes. This relatively rapid and transient increase in calcium levels was necessary for the increase in activity of the inducible form of calcium/calmodulin-dependent NO synthetase (50). However, calcium-stimulated changes in gene regulation generally occur over a period of hours (10). To our knowledge, even though recent studies suggested that calcium could be mobilized following cell stimulation with CPT (76) and VP16 (15), whether these agents could cause activation of a calcium-dependent transcription factor was unknown. Our calcium measurements using CEM cells demonstrated that the increases in intracellular calcium following CPT and VP16 exposure can occur with relatively slow kinetics, taking ∼60 min to reach significant levels (Fig. 2D; Table 1). While we found evidence that rapid calcium mobilization could occur transiently within 5 min after VP16 treatment of HEK293 cells (C. M. Berchtold, unpublished observations), our time course analyses using BAPTA-AM clearly demonstrated the critical role for a calcium-dependent process occurring between 60 and 90 min post-genotoxic stress induction to mediate NF-κB activation (Fig. 3). This time course of calcium requirement for the genotoxic stress-dependent NF-κB activation also contrasts with previous roles that were implicated in calcium-dependent NF-κB regulation. Previous studies showed that the calcium-dependent activation of NF-κB could be very rapid. For example, the activation of NF-κB with ionomycin and a phorbol ester occurs within minutes (∼15 min) of exposure in B cells through a calcium-mediated protein kinase C pathway (21, 79). Studies in neuronal cells also demonstrated a rapid calcium-induced NF-κB activation mediated by calmodulin-dependent kinase II within a similar time period (58). When we examined the role of PKC isoforms and calmodulin-dependent kinase II by means of chemical inhibitors, we failed to find evidence for their involvement in NF-κB activation by genotoxic stimuli (C. M. Berchtold, unpublished observations) (16). Our data are more consistent with a calcium-dependent process occurring between 60 and 90 min post-genotoxic stress induction (Fig. 3).

Is DNA damage per se required for calcium increases following exposure to the genotoxic agents? CPT and VP16 interact with the reaction intermediates between DNA topoisomerase I and II, respectively, leading to the generation of “cleavable complexes” in the nucleus (53). These lesions can generate DNA single- and double-strand breaks, thereby justifying their designation as “DNA damaging agents.” However, these agents can also induce other cell stresses in the form of oxidative stress (49), ceramide (77), and the ER stress protein response (72, 73). These different stress conditions can stimulate increases in intracellular calcium without the need for DNA damage (27). Moreover, the deregulation of calcium in isolated organelles such as mitochondria and ER can also occur with direct VP16 exposure (15). In the case of IR, oxidative stress induced by the ionization of water and macromolecules in cells, such as lipids and proteins (14), could be critical for calcium mobilization from the ER (85). While the magnitude of EGTA effect was modest in our studies (Fig. 1C), we cannot exclude the possibility that extracellular calcium could also be a critical source for intracellular calcium increases following CPT and VP16 exposure under certain conditions. For example, genotoxic agents could elicit a decrease in the ER calcium concentration, which could then signal for the influx of extracellular calcium (66). Finally, studies showed that cells containing a defective ATM were aberrant in the mobilization of calcium stimulated by serum (26). These studies suggested the possibility that an ATM-dependent mechanism could also contribute to the calcium increases induced by VP16 and CPT treatment. When we reduced the expression levels of ATM by means of specific siRNAs, we found a modest inhibitory effect on calcium mobilization in CEM cells (data not shown). We were unable to study the effect of chemical inhibitors against ATM (e.g., wortmannin) due to perturbation of the calcium measurement. Thus, we cannot currently exclude the potential involvement of ATM in regulating calcium release, and further in-depth analyses are required to determine the source and the mechanism of intracellular calcium increases induced by CPT and VP16. These studies will help sort out which exact cell stresses beyond DNA damage per se are necessary for activation of NF-κB by DNA-damaging agents.

Our molecular studies suggested that the step at which calcium imparts regulation on the NF-κB activation pathway induced by CPT and VP16 is likely at the NEMO export step. Ubiquitin appears to play a critical role in promoting NEMO nuclear export (91). A previous study suggested that monoubiquitination of the tumor suppressor p53 regulates its nuclear export (1). A ubiquitin-p53 fusion strategy was employed to demonstrate the role of monoubiquitination and inhibition by LMB, thus suggesting a role of CRM1 in mediating nuclear export of monoubiquitinated p53. Unlike the case with p53, our analyses indicated that nuclear export of NEMO induced by VP16 was insensitive to inhibition by LMB (Fig. 6B and C). This also contrasted with a previous study indicating that LMB can cause nuclear accumulation of NEMO in unstressed HeLa cells (89). To our knowledge, the only reported calcium-dependent nuclear export receptor is calreticulin (35, 36). However, our results indicated that calreticulin is not essential for NF-κB activation by VP16.

Our studies suggest that NEMO is complexed to Ran-GTP following a DNA damage stimulus and that BAPTA-AM does not appear to modulate these interactions (Fig. 7). Similarly, our molecular and biochemical analyses indicated that the upstream regulatory events invoked by genotoxic stress conditions, such as activation of ATM and NEMO sumoylation, are not mediated by calcium. Because Ran-GTP is normally coupled to an export receptor which, in turn, plays a prominent role in binding to the transporting cargo (29), we can infer from the VP16-inducible interaction between NEMO and Ran-GTP that a similar trimeric complex is probably assembled with a putative nuclear export receptor for NEMO, which is required for NEMO export and NF-κB activation. However, there is another regulatory step(s) described for the nuclear export of a protein subsequent to the formation of a Ran-GTP/nuclear export receptor/cargo trimeric complex but prior to the release of the cargo on the cytoplasmic surface of the nuclear pore complex. Nucleoporin proteins containing phenylalanine/glycine (FG) binding motifs line the inner surface of the nuclear pore (86). Interactions between different FG-containing nucleoporins and Ran-GTP-mediated cargos appear to differentially facilitate multiple export pathways through the nuclear pore (80). Interestingly, these FG-containing nucleoporins are in a native unfolded state which inherently makes the aqueous binding surface of these proteins highly susceptible to changes in temperature, pH, salts, and calcium (68, 88). Moreover, more global conformation changes of the nuclear pore complex can also occur with different calcium-metabolizing compounds (25). Therefore, a calcium-dependent step for nuclear export of NEMO may include any one of these known or unknown additional steps. Additionally, since BAPTA-AM did not perturb TNF-α-dependent NF-κB activation, we suggest that the calcium chelator is not a general inhibitor of nuclear export. BAPTA-AM did not apparently block the CRM1-dependent nuclear export of IκBα/NF-κB complexes required for TNFα-dependent NF-κB activation (38). Further studies are required to investigate this interesting mechanism.

While it was not the focus of the current study, unexpectedly, the results shown in Fig. 2A to C revealed that a specific extracellular milieu could impart dramatic effects on NF-κB activation in response to genotoxic stress agents. These observations suggest the possibility that NF-κB activation by certain DNA-damaging agents could be highly susceptible to subtle changes in the cellular microenvironment. Coupled with the notion that NF-κB can modulate survival and drug resistance of tumor cells (3, 5, 20, 46), the results suggest a novel possibility that specific variations in tumor microenvironments could selectively attenuate or augment the NF-κB response to DNA-damaging anticancer agents. Changes in pH, intracellular and extracellular calcium, osmolarity, and temperature appear to modulate NF-κB activation by DNA-damaging agents. Interestingly, some of these changes can be observed with neoplastic transformation, within tumor microenvironments in various cancer types, and during radiation therapy and chemotherapy (8, 33, 43, 64, 71, 92). Therefore, understanding the mechanisms responsible for enhancement (e.g., low pH, higher temperature) and the decrease (e.g., high osmolarity) of NF-κB activation may provide novel strategies to prevent NF-κB activation and to increase the efficacy of anticancer therapy.

Acknowledgments

We thank James Dahlberg for tsBN2 and BHK21 cell lines and discussions regarding nuclear export receptors. We also thank M. Michalak for providing the calreticulin knockout and matched mouse embryonic fibroblast lines. We also thank Kathy Schell of the UW Flow Cytometry Laboratory for help with flow analyses and the members of the Miyamoto Laboratory for their helpful discussions.

This work was supported by R01-CA77474 and R01-CA81065 from NIH and a Shaw Scientist Award from the Greater Milwaukee Foundation to S.M. Z.-H.W. is also funded by a special Fellowship from the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 30 October 2006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aggarwal, B. B. 2003. Signalling pathways of the TNFα superfamily: a double-edged sword. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3:745-756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akira, S., and K. Takeda. 2004. Toll-like receptor signalling. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4:499-511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amundson, S. A., M. Bittner, and A. J. Fornace. 2003. Functional genomics as a window on radiation stress signaling. Oncogene 22:5828-5833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bakkenist, C. J., and M. B. Kastan. 2003. DNA damage activates ATM through intermolecular autophosphorylation and dimer dissociation. Nature 421:499-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baldwin, A. S. 2001. Control of oncogenesis and cancer therapy resistance by the transcription factor NF-κB. J. Clin. Investig. 107:241-246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barrett, D. M., S. M. Black, H. Todor, R. K. Schmidt-Ullrich, K. S. Dawson, and R. B. Mikkelsen. 2005. Inhibition of protein-tyrosine phosphatases by mild oxidative stresses is dependent on S-nitrosylation. J. Biol. Chem. 280:14453-14461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beddow, A. L., S. A. Richards, N. R. Orem, and I. G. Macara. 1995. The Ran/TC4 GTPase-binding domain: identification by expression cloning and characterization of a conserved sequence motif. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:3328-3332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berridge, M. J. 1995. Calcium signalling and cell proliferation. Bioessays 17:491-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berridge, M. J. 1993. Inositol trisphosphate and calcium signalling. Nature 361:315-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berridge, M. J., M. D. Bootman, and H. L. Roderick. 2003. Calcium signalling: dynamics, homeostasis and remodelling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4:517-529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berridge, M. J., P. Lipp, and M. D. Bootman. 2000. The versatility and universality of calcium signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 1:11-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonizzi, G., and M. Karin. 2004. The two NF-κB activation pathways and their role in innate and adaptive immunity. Trends Immunol. 25:280-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bootman, M. D., and M. J. Berridge. 1996. Subcellular calcium signals underlying waves and graded responses in HeLa cells. Curr. Biol. 6:855-865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Breen, A. P., and J. A. Murphy. 1995. Reactions of oxyl radicals with DNA. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 18:1033-1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chandra, D., G. Choy, X. D. Deng, B. Bhatia, P. Daniel, and D. G. Tang. 2004. Association of active caspase 8 with the mitochondrial membrane during apoptosis: potential roles in cleaving BAP31 and caspase 3 and mediating mitochondrion-endoplasmic reticulum cross talk in etoposide-induced cell death. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:6592-6607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang, P. Y., and S. Miyamoto. 2006. NF-κB dimer exchange promotes a p21(waf1/cip1) superinduction response in human T leukemic cells. Mol. Cancer Res. 4:101-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen, Z. J. J. 2005. Ubiquitin signalling in the NF-κB pathway. Nat. Cell Biol. 7:758-765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheng, Y., J. E. Dahlberg, and E. Lund. 1995. Diverse effects of the guanine nucleotide exchange factor RCC1 on RNA transport. Science 267:1807-1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Criswell, T., K. Leskov, S. Miyamoto, G. B. Luo, and D. A. Boothman. 2003. Transcription factors activated in mammalian cells after clinically relevant doses of ionizing radiation. Oncogene 22:5813-5827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cusack, J. C., R. Liu, and A. S. Baldwin. 2000. Inducible chemoresistance to 7-ethyl-10 [4-(1-piperidino)-1-piperidino] carbonyloxycamptothecin (CPT-11) in colorectal cancer cells and a xenograft model is overcome by inhibition of NF-κB activation. Cancer Res. 60:2323-2330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dolmetsch, R. E., R. S. Lewis, C. C. Goodnow, and J. I. Healy. 1997. Differential activation of transcription factors induced by calcium response amplitude and duration. Nature 386:855-858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dolmetsch, R. E., K. Xu, and R. S. Lewis. 1998. Calcium oscillations increase the efficiency and specificity of gene expression. Nature 392:933-936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ducut Sigala, J. L., V. Bottero, D. B. Young, A. Shevchenko, F. Mercurio, and I. M. Verma. 2004. Activation of transcription factor NF-κB requires ELKS, an IκB kinase regulatory subunit. Science 304:1963-1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eastman, A. 1995. Assays for DNA fragmentation, endonucleases, and intracellular pH and calcium associated with apoptosis. Methods Cell Biol. 46:41-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Erickson, E. S., O. L. Mooren, D. Moore, J. R. Krogmeier, and R. C. Dunn. 2006. The role of nuclear envelope calcium in modifying nuclear pore complex structure. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 84:309-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Famulski, K. S., R. S. Al-Hijailan, K. Dobler, M. Pienkowska, F. Al-Mohanna, and M. C. Paterson. 2003. Aberrant sensing of extracellular calcium by cultured ataxia telangiectasia fibroblasts. Oncogene 22:471-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferri, K. F., and G. Kroemer. 2001. Organelle-specific initiation of cell death pathways. Nat. Cell Biol. 3:E255-E63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ghosh, S., and M. Karin. 2002. Missing pieces in the NF-κB puzzle. Cell 109:S81-S96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gorlich, D., and U. Kutay. 1999. Transport between the cell nucleus and the cytoplasm. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 15:607-660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guse, A. H., E. Roth, and F. Emmrich. 1993. Intracellular calcium pools in Jurkat T-lymphocytes. Biochem. J. 291:447-451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Habraken, Y., B. Piret, and J. Piette. 2001. S phase dependence and involvement of NF-κB activating kinase to NF-κB activation by camptothecin. Biochem. Pharmacol. 62:603-616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harhaj, E. W., and S. C. Sun. 1999. Regulation of RelA subcellular localization by a putative nuclear export signal and p50. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:7088-7095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harris, A. L. 2002. Hypoxia-a key regulatory factor in tumour growth. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2:38-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hayden, M. S., and S. Ghosh. 2004. Signaling to NF-κB. Genes Dev. 18:2195-2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holaska, J. M., B. E. Black, D. C. Love, J. A. Hanover, J. Leszyk, and B. M. Paschal. 2001. Calreticulin is a receptor for nuclear export. J. Cell Biol. 152:127-140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holaska, J. M., B. E. Black, F. Rastinejad, and B. M. Paschal. 2002. Calcium-dependent nuclear export mediated by calreticulin. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:6286-6297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang, T. T., S. L. Feinberg, S. Suryanarayanan, and S. Miyamoto. 2002. The zinc finger domain of NEMO is selectively required for NF-κB activation by UV radiation and topoisomerase inhibitors. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:5813-5825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang, T. T., N. Kudo, M. Yoshida, and S. Miyamoto. 2000. A nuclear export signal in the N-terminal regulatory domain of IκBα controls cytoplasmic localization of inactive NF-κB/IκBα complexes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:1014-1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang, T. T., and S. Miyamoto. 2001. Postrepression activation of NF-κB requires the amino-terminal nuclear export signal specific to IκBα. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:4737-4747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang, T. T., S. M. Wuerzberger-Davis, B. J. Seufzer, S. D. Shumway, T. Kurama, D. A. Boothman, and S. Miyamoto. 2000. NF-κB activation by camptothecin. A linkage between nuclear DNA damage and cytoplasmic signaling events. J. Biol. Chem. 275:9501-9509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang, T. T., S. M. Wuerzberger-Davis, Z. H. Wu, and S. Miyamoto. 2003. Sequential modification of NEMO/IKKγ by SUMO-1 and ubiquitin mediates NF-κB activation by genotoxic stress. Cell 115:565-576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hur, G. M., J. Lewis, Q. F. Yang, Y. Lin, H. Nakano, S. Nedospasov, and Z. G. Liu. 2003. The death domain kinase RIP has an essential role in DNA damage-induced NF-κB activation. Genes Dev. 17:873-882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Izumi, H., T. Torigoe, H. Ishiguchi, H. Uramoto, Y. Yoshida, M. Tanabe, T. Ise, T. Murakami, T. Yoshida, M. Nomoto, and K. Kohno. 2003. Cellular pH regulators: potentially promising molecular targets for cancer chemotherapy. Cancer Treat. Rev. 29:541-549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Janssens, S., A. Tinel, S. Lippens, and J. Tschopp. 2005. PIDD mediates NF-κB activation in response to DNA damage. Cell 123:1079-1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kao, J. P. 1994. Practical aspects of measuring calcium with fluorescent indicators. Methods Cell Biol. 40:155-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Karin, M., Y. Cao, F. R. Greten, and Z. W. Li. 2002. NF-κB in cancer: from innocent bystander to major culprit. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2:301-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Karin, M., and A. Lin. 2002. NF-κB at the crossroads of life and death. Nat. Immunol. 3:221-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Karin, M., Y. Yamamoto, and Q. M. Wang. 2004. The IKK/NF-κB system: a treasure trove for drug development. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 3:17-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kurosu, T., T. Fukuda, T. Miki, and O. Miura. 2003. BCL6 overexpression prevents increase in reactive oxygen species and inhibits apoptosis induced by chemotherapeutic reagents in B-cell lymphoma cells. Oncogene 22:4459-4468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Leach, J. K., S. M. Black, R. K. Schmidt-Ullrich, and R. B. Mikkelsen. 2002. Activation of constitutive nitric-oxide synthase activity is an early signaling event induced by ionizing radiation. J. Biol. Chem. 277:15400-15506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li, N. X., S. Banin, H. H. Quyang, G. C. Li, G. Courtois, Y. Shiloh, M. Karin, and G. Rotman. 2001. ATM is required for IκB kinase (IKK) activation in response to DNA double strand breaks. J. Biol. Chem. 276:8898-8903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li, N. X., and M. Karin. 1998. Ionizing radiation and short wavelength uv activate NF-κB through two distinct mechanisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:13012-13017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li, T. K., and L. F. Liu. 2001. Tumor cell death induced by topoisomerase-targeting drugs. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 41:53-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lounsbury, K. M., S. A. Richards, K. L. Carey, and I. G. Macara. 1996. Mutations within the Ran/TC4 GTPase. Effects on regulatory factor interactions and subcellular localization. J. Biol. Chem. 271:32834-32841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Luo, J. L., H. Kamata, and M. Karin. 2005. IKK/NF-κB signaling: balancing life and death-a new approach to cancer therapy. J. Clin. Investig. 115:2625-2632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mabb, A. M., S. M. Wuerzberger-Davis, and S. Miyamoto. 2006. PIASy mediates NEMO sumoylation and NF-κB activation in response to genotoxic stress. Nat. Cell Biol. 8:986-993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Malek, S., Y. Chen, T. Huxford, and G. Ghosh. 2001. I kBb but not IkBa, functions as a classical cytoplasmic inhibitor of NF-κB dimers by masking both NF-κB nuclear localization sequences in resting cells. J. Biol. Chem. 276:45225-45235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Meffert, M. K., J. M. Chang, B. J. Wiltgen, M. S. Fanselow, and D. Baltimore. 2003. NF-κB functions in synaptic signaling and behavior. Nat. Neurosci. 6:1072-1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mesaeli, N., K. Nakamura, E. Zvaritch, P. Dickie, E. Dziak, K. H. Krause, M. Opas, D. H. MacLennan, and M. Michalak. 1999. Calreticulin is essential for cardiac development. J. Cell Biol. 144:857-868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mikkelsen, R. B., and P. Wardman. 2003. Biological chemistry of reactive oxygen and nitrogen and radiation-induced signal transduction mechanisms. Oncogene 22:5734-5754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Miyamoto, S., T. T. Huang, S. Wuerzberger-Davis, W. G. Bornmann, J. J. Pink, C. Tagliarino, T. J. Kinsella, and D. A. Boothman. 2000. Cellular and molecular responses to topoisomerase I poisons. Exploiting synergy for improved radiotherapy. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 922:274-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nam, J. H., S. S. Yoon, T. J. Kim, D. Y. Uhm, and S. J. Kim. 2003. Slow and persistent increase of calcium in response to ligation of surface IgM in WEHI231 cells. FEBS Lett. 535:113-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nishitani, H., M. Ohtsubo, K. Yamashita, H. Iida, J. Pines, H. Yasudo, Y. Shibata, T. Hunter, and T. Nishimoto. 1991. Loss of RCC1, a nuclear DNA-binding protein, uncouples the completion of DNA replication from the activation of cdc2 protein kinase and mitosis. EMBO J. 10:1555-1564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Orive, G., S. J. Reshkin, S. Harguindey, and J. L. Pedraz. 2003. Hydrogen ion dynamics and the Na+/H+ exchanger in cancer angiogenesis and antiangiogenesis. Br. J. Cancer 89:1395-1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Panta, G. R., S. Kaur, L. G. Cavin, M. L. Cortes, F. Mercurio, L. Lothstein, T. W. Sweatman, M. Israel, and M. Arsura. 2004. ATM and the catalytic subunit of DNA-dependent protein kinase activate NF-κB through a common MEK extracellular signal-regulated kinase/p90(rsk) signaling pathway in response to distinct forms of DNA damage. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:1823-1835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Parekh, A. B., and J. W. Putney. 2005. Store-operated calcium channels. Physiol. Rev. 85:757-810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Patterson, R. L., D. B. van Rossum, D. L. Ford, K. J. Hurt, S. S. Bae, P. G. Suh, T. Kurosaki, S. H. Snyder, and D. L. Gill. 2002. Phospholipase Cγ is required for agonist-induced calcium entry. Cell 111:529-541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Paulillo, S. M., M. A. Powers, K. S. Ullman, and B. Fahrenkrog. 2006. Changes in nucleoporin domain topology in response to chemical effectors. J. Mol. Biol. 363:39-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Piret, B., S. Schoonbroodt, and J. Piette. 1999. The ATM protein is required for sustained activation of NF-κB following DNA damage. Oncogene 18:2261-2271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pozzan, T., D. P. Lew, C. B. Wollheim, and R. Y. Tsien. 1983. Is cytosolic ionized calcium regulating neutrophil activation? Science 221:1413-1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Quinlan, D. C., J. R. Parnes, R. Shalom, T. Q. Garvey III, K. J. Isselbacher, and J. Hochstadt. 1976. Sodium-stimulated amino acid uptake into isolated membrane vesicles from Balb/c 3T3 cells transformed by simian virus 40. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 73:1631-1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Reddy, R. K., J. Lu, and A. S. Lee. 1999. The endoplasmic reticulum chaperone glycoprotein GRP94 with calcium-binding and antiapoptotic properties is a novel proteolytic target of calpain during etoposide-induced apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 274:28476-28483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Reddy, R. K., C. Mao, P. Baumeister, R. C. Austin, R. J. Kaufman, and A. S. Lee. 2003. Endoplasmic reticulum chaperone protein GRP78 protects cells from apoptosis induced by topoisomerase inhibitors: role of ATP binding site in suppression of caspase-7 activation. J. Biol. Chem. 278:20915-20924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Richards, S. A., K. L. Carey, and I. G. Macara. 1997. Requirement of guanosine triphosphate-bound ran for signal-mediated nuclear protein export. Science 276:1842-1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Schwoebel, E. D., T. H. Ho, and M. S. Moore. 2002. The mechanism of inhibition of Ran-dependent nuclear transport by cellular ATP depletion. J. Cell Biol. 157:963-974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sedarous, M., E. Keramaris, M. O'Hare, E. Melloni, R. S. Slack, J. S. Elce, P. A. Greer, and D. S. Park. 2003. Calpains mediate p53 activation and neuronal death evoked by DNA damage. J. Biol. Chem. 278:26031-26038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Senchenkov, A., D. A. Litvak, and M. C. Cabot. 2001. Targeting ceramide metabolism-a strategy for overcoming drug resistance. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 93:347-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Smith, A. E., B. M. Slepchenko, J. C. Schaff, L. M. Loew, and I. G. Macara. 2002. Systems analysis of Ran transport. Science 295:488-491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sommer, K., B. C. Guo, J. L. Pomerantz, A. D. Bandaranayake, M. E. Moreno-Garcia, Y. L. Ovechkina, and D. J. Rawlings. 2005. Phosphorylation of the CARMA1 linker controls NF-κB activation. Immunity 23:561-574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Strawn, L. A., T. Shen, N. Shulga, D. S. Goldfarb, and S. R. Wente. 2004. Minimal nuclear pore complexes define FG repeat domains essential for transport. Nat. Cell Biol. 6:197-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sun, L. J., and Z. J. Chen. 2004. The novel functions of ubiquitination in signaling. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 16:119-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tam, W. F., L. H. Lee, L. Davis, and R. Sen. 2000. Cytoplasmic sequestration of Rel proteins by IκBα requires CRM1-dependent nuclear export. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:2269-2284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tam, W. F., and R. J. Sen. 2001. IκB family members function by different mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 276:7701-7704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Thastrup, O., P. J. Cullen, B. K. Drobak, M. R. Hanley, and A. P. Dawson. 1990. Thapsigargin, a tumor promoter, discharges intracellular calcium stores by specific inhibition of the endoplasmic reticulum calcium-ATPase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:2466-2470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Todd, D. G., and R. B. Mikkelsen. 1994. Ionizing radiation induces a transient increase in cytosolic free calcium. Cancer Res. 54:5224-5230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tran, E. J., and S. R. Wente. 2006. Dynamic nuclear pore complexes: life on the edge. Cell 125:1041-1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tsien, R. Y. 1980. New calcium indicators and buffers with high selectivity against magnesium and protons: design, synthesis, and properties of prototype structures. Biochemistry 9:2396-2404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Uversky, V. N. 2002. What does it mean to be natively unfolded? Eur. J. Biochem. 269:2-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Verma, U. N., Y. Yamamoto, S. Prajapati, and R. B. Gaynor. 2004. Nuclear role of IκB kinaseγ/NF-κB essential modulator (IKKγ/NEMO) in NF-κB-dependent gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 279:3509-3515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Weil, R., and A. Israel. 2004. T-cell-receptor- and B-cell-receptor-mediated activation of NF-κB in lymphocytes. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 16:374-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]