Abstract

CHK2 and p53 are frequently mutated in human cancers. CHK2 is known to phosphorylate and stabilize p53. CHK2 has also been implicated in DNA repair and apoptosis induction. However, whether p53 affects CHK2 activation and whether CHK2 activation modulates chemosensitivity are unclear. In this study, we found that in response to the DNA damage agent, irofulven, CHK2 activation, rather than its expression, is inversely correlated to p53 status. Irofulven inhibits DNA replication and induces chromosome aberrations (breaks and radials) and p53-dependent cell cycle arrest. Pretreatment of cells with the DNA polymerase inhibitor, aphidicolin, resulted in reduction of irofulven-induced CHK2 activation and foci formation, indicating that CHK2 activation by irofulven is replication-dependent. Furthermore, by using ovarian cancer cell lines expressing dominant-negative CHK2 and CHK2-knockout HCT116 cells, we found that CHK2 activation contributes to the control of S and G2/M cell cycle arrests, but not chemosensitivity to irofulven. Overall, this study demonstrates that in response to irofulven-induced DNA damage, the activation of CHK2 is dependent on DNA replication and related to p53 status. By controlling cell cycle arrest and DNA replication, p53 affects CHK2 activation. CHK2 activation contributes to cell cycle arrest, but not chemosensitivity.

Keywords: CHK2, p53, replication, chemosensitivity, cell cycle, irofulven

1. Introduction

In response to DNA damage, cells evoke signal transduction pathways to arrest at G1/S, S or G2/M phases, allowing time to deal with the insult [1, 2]. DNA damage activates ATM (ataxia telangiectasia-mutated) and/or ATR (ATM-Rad3-related) kinases, which in turn phosphorylate and activate downstream effector kinases, CHK1 and CHK2. ATM phosphorylates CHK2 on Thr68 leading to CHK2 kinase activation, while ATM and ATR phosphorylate CHK1 on Ser317 and Ser345 resulting in its activation. Activation of CHK1 and CHK2 regulates S phase by phosphorylating CDC25A, or the G2/M transition by phosphorylating CDC25C [2-4]. ATM and ATR phosphorylate p53 on Ser15; and CHK1 and CHK2 phosphorylate p53 on Ser20, leading to its accumulation and activation [2-4]. Activation of p53 initiates cell cycle arrest and DNA repair-related genes such as p21, GADD45 and 14-3-3δ, which leads to G1 and G2 arrest.

Tumor suppressors p53 and CHK2 are frequently mutated in human cancers [5, 6]. Besides their roles in cell cycle control, p53 and CHK2 are also involved in regulating DNA repair and apoptosis [5-7]. p53 promotes DNA repair or apoptosis by directly regulating the expression of genes such as p48, DR5, BAX, PUMA and NOXA [2, 8]. CHK2 (cds1) in fission yeast was shown to interact with RAD60, a protein required for recombinational repair, at stalled replication forks [9]. In mammalian cells, it was shown that CHK2 promotes homologous recombination (HR) and non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ) of DNA double-strand breaks through phosphorylation of BRCA1 on serine 988 [10-13].

CHK2 has also been implicated in apoptosis induction. However, there are conflicting studies. Some studies found that CHK2 is a negative regulator of mitotic catastrophe, and inhibition of CHK2 sensitized cells to chemotherapy-induced apoptosis [14, 15]. Other studies found that CHK2 is involved in apoptosis induction [16-23]. Additional studies indicated that CHK2 induces apoptosis by activating E2F1, which in turn up-regulates its target genes INK4a/ARF, Apaf-1, caspase-7, p73 and p53 [24-26].

While many studies have investigated how CHK2 activates and stabilizes p53 [6, 17, 27-29], the possible role of p53 in regulating CHK2 protein level or activity has not been well studied. An inverse correlation between p53 and CHK2 expression has been reported in tumor cell lines and tissue specimens [30, 31]. A recent report suggested that p53 negatively regulates CHK2 expression by modulating the function of transcription factor NF-Y [32].

Given the critical roles that CHK2 plays in cell cycle control, DNA repair and apoptosis, it is still unclear whether it can ultimately affect chemosensitivity. In this study, we investigated the possible role that p53 plays in CHK2 activation and whether CHK2 activation will affect chemosensitivity in response to the DNA damage agent, irofulven. Irofulven (6-hydroxymethylacylfulvene, NSC#: 683863) is a semi-synthetic analog of mushroom-derived illudin toxins. Preclinical studies and clinical trials have demonstrated that it is effective against several tumor cell types [33-41]. It was previously demonstrated that irofulven activates ATM and its targets, NBS1, SMC1, CHK2 and p53 [42]. Here, we found that CHK2 activation is DNA replication-dependent and related to p53 status. By controlling cell cycle arrest and DNA replication, p53 affects CHK2 activation. Furthermore, we demonstrated that CHK2 activation contributes to the control of S and G2/M cell cycle arrest, but not chemosensitivity, in response to irofulven-induced DNA damage.

2. Materials and Methods

Cell culture

All cell lines were maintained in various media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum in a 37°C incubator with 5% CO2 atmosphere. Ovarian cancer cell lines A2780 and CAOV3 were cultured in RPMI 1640. Colon cancer cell line HCT116 and its p53-knockout (HCT116 p53−/−) [43] and CHK2-knockout (HCT116 CHK2−/−) cells [44] (generously provided by Prof. Bert Vogelstein, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD) were cultured in McCoy's 5A medium.

Clonogenic survival assay

To determine chemosensitivity and 1xIC50 concentration, the clonogenic survival assay was performed on 60-mm cell culture dishes as described previously [42]. Cells were treated with different concentrations of irofulven for one hour followed by drug-free incubations for about 10 days. Colonies were stained with crystal violet and counted if 50 or more cells were present.

Western blotting

Western blot was performed as described previously [42]. The antibodies used included: monoclonal anti-actin (Sigma, St Louis, MO), polyclonal anti-phosphorylated CHK2 on Thr 68 and anti-CHK2 (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA), monoclonal anti-p53, polyclonal anti-p21, anti-cyclin E, A, and B1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), and monoclonal anti-HA (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN).

Propidium iodide staining and flow cytometry

Cells were harvested, washed once with cold PBS and fixed in 75% ethanol/PBS. After washing twice with PBS, cells were re-suspended in PBS containing 10 μg/ml propidium iodide, 20 μg/ml RNase A, 0.1% sodium citrate and 0.1% Triton X-100. Cells were analyzed by FACSCalibur with CellquestPro software (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). Cell cycle distributions were analyzed by ModFit v3.0 software (Verity, Topsham, ME).

Metaphase spread

Cells were treated with irofulven for one hour followed by 24 hours of drug-free incubation. Colcemid (400 ng/ml) (Biosciences, La Jolla, CA) was added to medium four hours before harvesting. After trypsinization, cells were washed with PBS. Cell pellets were re-suspended in 75 mM KCl and placed in a 37°C incubator for eight minutes. After centrifugation, cells were fixed using 3:1 absolute methanol to glacial acetic acid at 4°C for two hours and then washed twice with fixative. Cells were re-suspended in fixative and dropped onto slides. Slides were air-dried at room temperature and stained with 5% Gurr's Giemsa stain (Biomedical Specialties, Santa Monica, CA) for seven minutes. Slides were rinsed twice with distilled water and air-dried. The images were recorded with a Leica DMR microscope (Bannockburn, IL) and Applied Imaging digital system (San Jose, CA).

BrdU incorporation and flow cytometry

BrdU (10 μM) (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) was added to cell culture 20 minutes before adding irofulven. Cells were harvested at different time points, washed once with cold PBS, and fixed in 75% ethanol/PBS. Staining for BrdU and flow cytometry were performed as described previously [42].

Immunofluorescent staining

Cells were plated on cover-slips and treated with irofulven for one hour followed by 12 hours of drug-free incubation. Cells were fixed and stained with polyclonal antibody against phosphorylated CHK2 on Thr 68 (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA). After staining with Alexafluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), slides were mounted with Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) containing 5 ng/ml of DAPI. Staining images were captured by an Olympus Provis AX70 fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Melville, NY), and Spot digital camera and software (Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Height, MI).

Stable transfection of dominant-negative CHK2

The HA-tagged dominant-negative CHK2 (CHK2 kinase-dead, CHK2.kd) cDNA was PCR-amplified from the pEF-BOS-CHK2.kd vector [45] (generously provided by Dr. Jann N. Sarkaria, Mayo Clinic and Foundation, Rochester, MN) and sub-cloned into the pCIneo vector (Promega, Madison, WI). The resulting plasmid was verified by DNA sequencing. The vector and HA-tagged CHK2.kd plasmids were subsequently transfected into the ovarian cancer cell line CAOV3. Stable cell lines harboring the vector and CHK2.kd were established by selecting in media containing G418 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

Immunoprecipitation and in vitro kinase assay

The in vitro kinase assay was performed as described previously [46]. Immunoprecipitation was performed with polyclonal antibody against CHK2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). The GST-CDC25C200-256 (generously provided by Dr. Jann N. Sarkaria, Mayo Clinic and Foundation, Rochester, MN) fusion proteins were expressed in bacteria and purified by affinity chromatography as described [45]. The purified GST-CDC25C200-256 fusion proteins were used as the substrate.

RDS assay

The radioresistant DNA synthesis (RDS) assay was performed as described previously [47]. Briefly, cells in the logarithmic phase of growth were pre-labeled by culturing in medium containing 10 nCi of [14C]-thymidine (PerkinElmer, Boston, MA) for 24 hours. The medium was then replaced with normal medium, and cells were incubated for another 24 hours. Cells were treated with irofulven for one hour and incubated in drug-free medium for three hours. Cells were then pulse-labeled with 2.5 μCi of [3H]-thymidine (PerkinElmer, Boston, MA) for 15 minutes. Cells were harvested, washed twice with PBS, and fixed in 70% methanol for 30 minutes. Cells were then transferred to Whatman filters (Whatman, Clifton, NJ) and washed sequentially with 70% and then 95% methanol. The filters were air-dried and the amount of radioactivity was quantified in a Wallac 1410 liquid scintillation counter (PerkinElmer, Downers Grove, IL). The resulting ratio of 3H to 14C counts per minute, corrected for channel crossover, was a measure of DNA synthesis.

Phosphorylated histone H3 staining and flow cytometry

Phospho-histone H3 staining was done as described previously [47]. Briefly, cells were treated with irofulven for one hour followed by one or three-hour of drug-free incubation. Cells were harvested and fixed in 70% ethanol. The fixed cells were washed twice with PBS and made permeable with 0.25% Triton X-100 in PBS on ice for 10 minutes. Cells were rinsed in 1% BSA/PBS and then stained with rabbit anti-phospho-S10 histone H3 antibody (Upstate, Charlottesville, VA) for two hours at room temperature. Cells were rinsed in 1% BSA/PBS and incubated with Alexafluor 488-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody for 30 minutes at room temperature. Cells were washed twice with PBS and suspended in PBS containing propidium iodide (0.25 μg/ml) and RNase A (20 μg/ml). Flow cytometry was performed on FACSCalibur with CellquestPro software (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). Thirty-thousand events were recorded for each sample. The percentage of mitotic cells was determined as those cells that were Alexafluor-positive and contained 4N DNA content.

3. Results

CHK2 activation induced by irofulven is related to p53 status

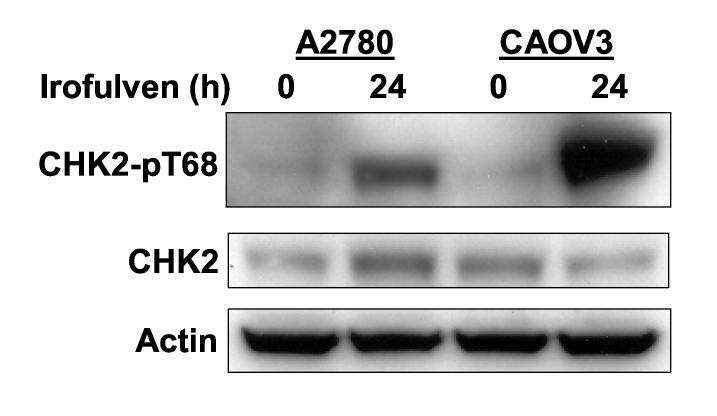

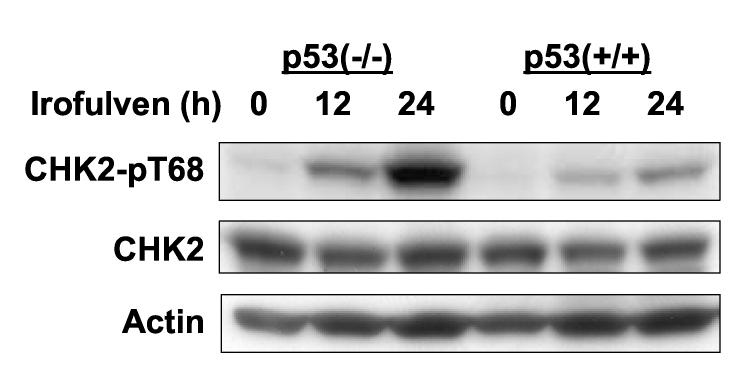

CHK2 is phosphorylated on Thr 68 in response to DNA damage, followed by oligomerization and auto-phosphorylation resulting in its activation [48-53]. CHK2 is known to phosphorylate and activate p53 [6, 17, 27-29]. Whether p53 will affect CHK2 activation in response to DNA damage is unclear. To investigate the roles that p53 might play in CHK2 activation, we determined CHK2 kinase activation by assessing Thr 68 phosphorylation using Western blot in p53-proficient and deficient cells after irofulven treatment. We found that CHK2 activation, rather than its expression, is inversely correlated to p53 status. Stronger CHK2 activation was observed in p53-mutated ovarian cancer cells (CAOV3) and p53-knockout colon cancer cells (HCT116 p53−/−) than in p53 wild-type ovarian cancer cells (A2780) and parental HCT116 (p53+/+) cells after irofulven treatment (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

CHK2 activation induced by irofulven is related to p53 status. A and B, Ovarian cancer cell lines A2780 (p53 wild-type) and CAOV3 (p53-mutated) (A) and colon cancer cell line HCT116 and its p53-knockout subline (p53−/−) (B) were treated with 1xIC50 concentrations of irofulven (0.8, 0.9 and 2.8 μM for A2780, CAOV3 and HCT116 cells, respectively) for one hour followed by 12 or 24 hours of drug-free incubations. CHK2 activation was determined by Western blot analysis with antibody recognizing Thr 68-phosphorylated CHK2 (CHK2-pT68). Blots for CHK2 and actin served as the loading control.

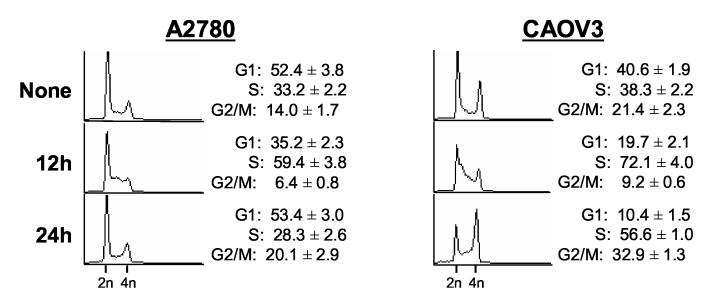

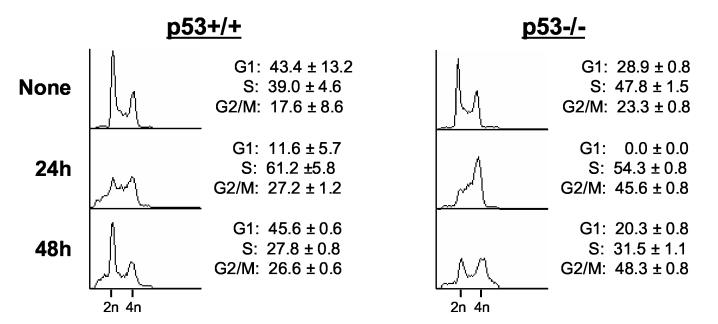

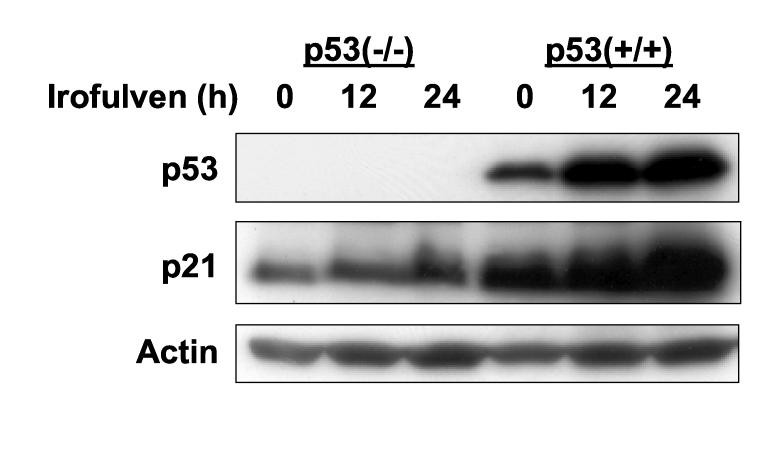

Irofulven induces p53-dependent cell cycle arrest

Since CHK2 activation is related to p53 status in response to irofulven-induced DNA damage, we hypothesized that CHK2 activation might be related to p53-dependent cell cycle arrest and DNA replication. We analyzed the cell cycle profiles in ovarian cancer cells A2780 (p53 wild-type) and CAOV3 (p53-mutated) using PI staining and FACS analysis. As shown in Fig. 2A, twelve hours after drug treatment, A2780 cells displayed loss of G1 and increase of S phase. By 24 hours, the G1 peak was restored and there was a slight increase in G2/M population. In CAOV3 cells, twelve hours after drug treatment, loss of G1 and an increase of S phase were observed. By 24 hours, S phase arrest and G2/M accumulation were observed (Fig. 2A).

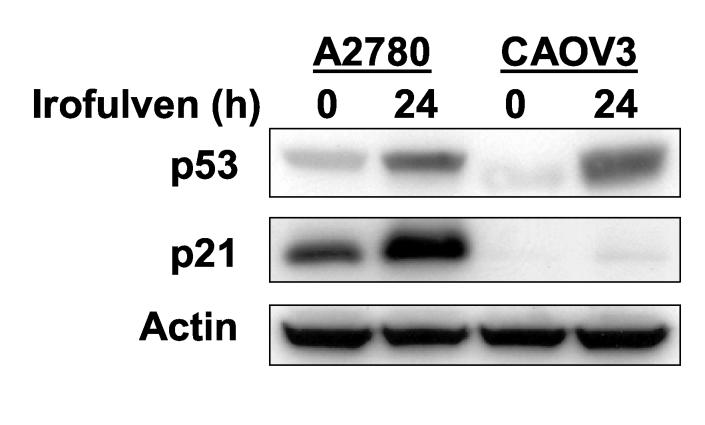

Fig. 2.

Irofulven induces p53-dependent cell cycle arrest. A through D, A2780, CAOV3, HCT116 p53+/+ and HCT116 p53−/− cells were treated with 2.8 μM of irofulven for one hour followed by 12, 24 or 48 hours of drug-free incubations. Cell cycle distributions were assessed by propidium iodide (PI) staining and FACS analysis (A and C). p53 accumulation and p21 induction were determined by Western blot analysis. Actin was blotted as the loading control (B and D).

Consistent with the p53-dependent cell cycle arrest observed by FACS analysis, p53 accumulation and p21 induction after irofulven treatment were observed in p53 wild-type A2780 cells. In p53-mutated CAOV3 cells, the accumulation of p53 protein was observed, but p21 induction was largely impaired (Fig. 2B). These data together indicated that irofulven induces p53-dependent cell cycle arrest.

To further confirm that irofulven induces p53-dependent cell cycle arrest, the cell cycle profiles of HCT116 p53+/+ and HCT 116 p53 −/− cells were analyzed. These cells grew relatively slower than A2780 and CAOV3 cells, therefore, we examined the cell cycle profiles at 24 and 48 hours after drug treatment. As shown in Fig. 2C, twenty-four hours after drug exposure, both HCT116 p53+/+ and HCT116 p53−/− cells displayed some S phase arrest; while HCT116 p53−/− cells showed complete loss of G1 and more accumulation of G2/M compared with parental HCT116 cells. Forty-eight hours after drug treatment, parental HCT116 cells were mainly arrested at G1 phase, while large populations of HCT116 p53−/− cells were arrested at G2/M phases (Fig. 2C). Corresponding to p53-dependent cell cycle arrest, p53 accumulation and p21 induction were observed in parental HCT116 cells, but not in p53-knockout cells after irofulven treatment (Fig. 2D). Taken together, these results demonstrated that irofulven induces p53-dependent cell cycle arrest; p53 wild-type cells mainly arrested at G1/S phases, while p53-mutated or p53-null cells arrested at S and G2/M phases.

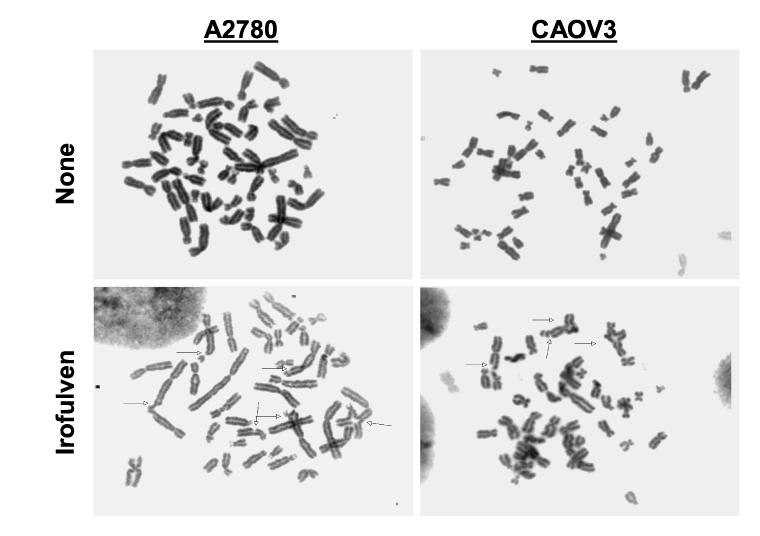

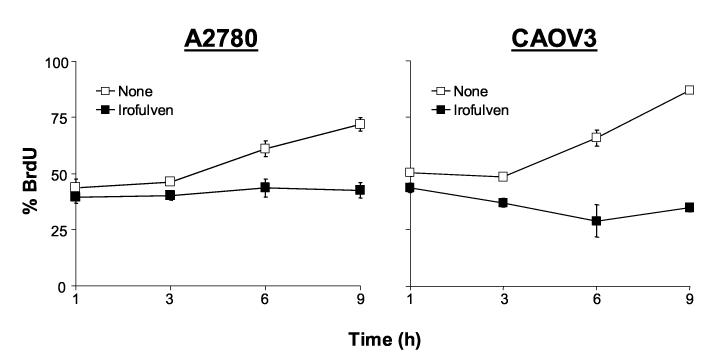

Irofulven induces chromosome aberrations and inhibits DNA synthesis

To further explore the mechanisms that cause p53-dependent cell cycle arrest and p53-related CHK2 activation, we assessed chromosome damage by metaphase spread experiment and DNA replication by BrdU incorporation and FACS analysis. Analysis of metaphase cells clearly indicated that irofulven induces chromosome breaks, triradials and quadriradials in A2780 and CAOV3 cells (Fig. 3A). Similarly, chromosome breaks and radials were also observed in HCT116 p53+/+ and HCT116 p53−/− cells after treatment (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Irofulven induces chromosome aberrations and inhibits DNA synthesis. A, A2780 and CAOV3 cells were treated with 1xIC50 concentrations of irofulven (0.8 and 0.9 μM, respectively) for one hour followed by 24 hours of drug-free incubations. Metaphase spread staining was performed. Arrows indicate chromosome breaks, triradials and quadriradials. B, A2780 and CAOV3 cells were treated with 1xIC50 concentrations of irofulven for one to nine hours. DNA synthesis rate was assessed by BrdU incorporation and FACS analysis. The mean and standard deviation of triplicate experiments were shown.

Consistent with the observed chromosome damage, DNA synthesis was completely inhibited in A2780 and CAOV3 cells in the presence of irofulven, as determined by BrdU incorporation and FACS analysis (Fig. 3B). Therefore, these data demonstrate that irofulven induces chromosome damage, stalled DNA replication and p53-dependent cell cycle arrest.

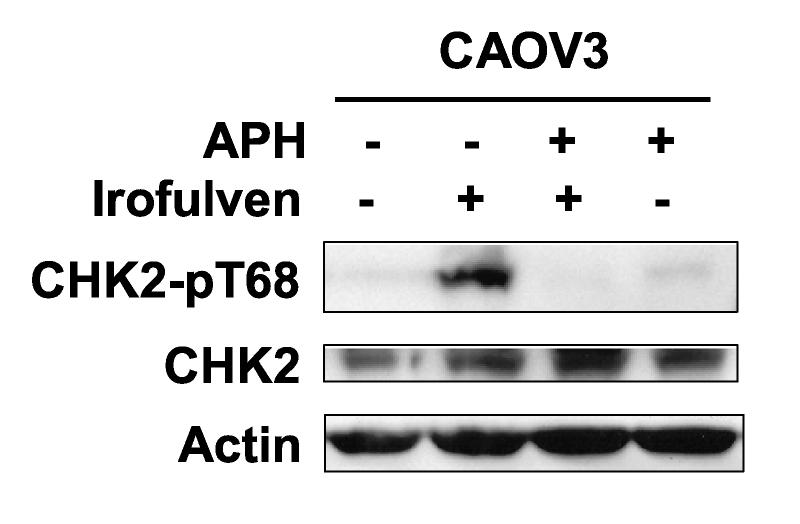

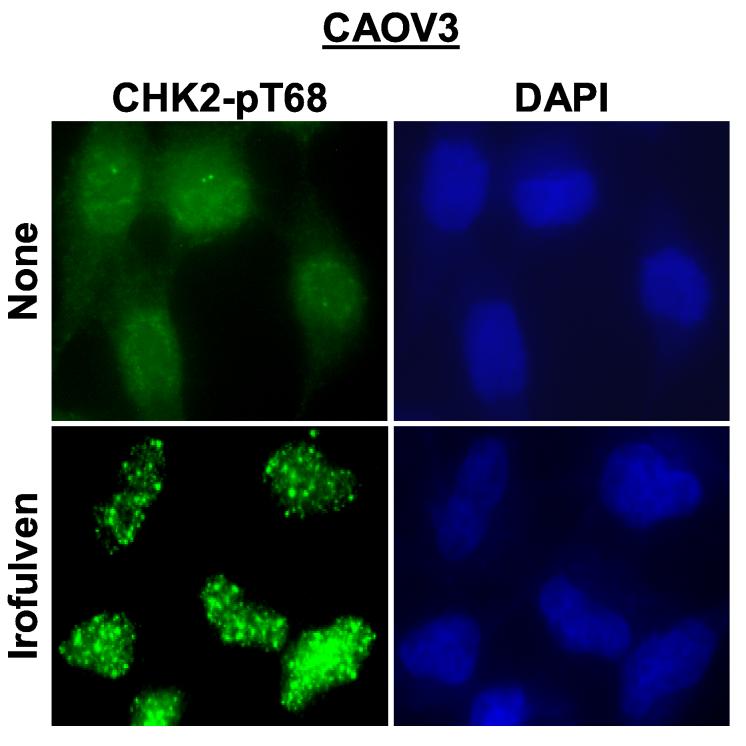

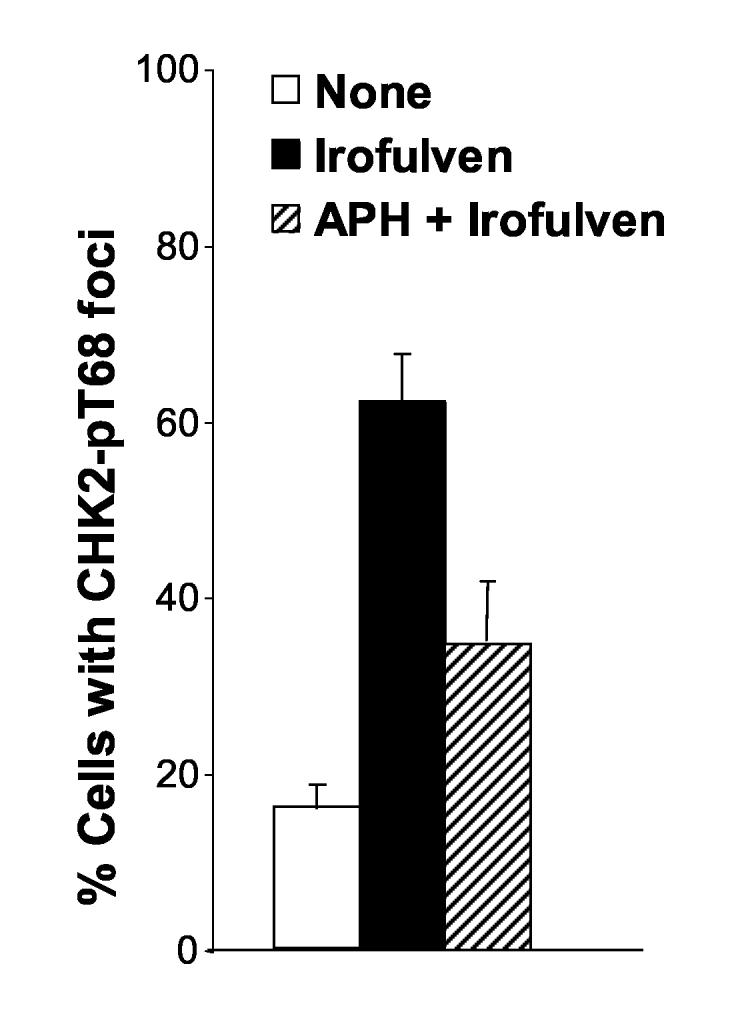

CHK2 activation induced by irofulven is DNA replication-dependent

We observed that irofulven induces chromosome aberrations, stalled DNA replication and p53-dependent cell cycle arrest; and CHK2 activation is related to p53 status. We hypothesized that CHK2 might be activated by stalled DNA replication, therefore, it might be replication-dependent and affected by p53-dependent cell cycle arrest. To test this, CAOV3 cells were pretreated with aphidicolin, a specific inhibitor of DNA polymerase α [54]. It was demonstrated that CHK2 activation by irofulven was indeed reduced by aphidicolin treatment (Fig. 4A). Similar reduction of CHK2 activation by aphidicolin was also observed in HCT116 p53−/− cells (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

CHK2 activation induced by irofulven is DNA replication-dependent. CAOV3 cells were pretreated with aphidicolin (APH, 1 μM, 2 h) before being treated with 0.9 μM of irofulven for one hour followed by 12 hours of incubation in medium containing APH. A, CHK2 activation was determined by Western blot analysis with antibody recognizing Thr 68-phosphorylated CHK2. Blots for CHK2 served as the loading control. B and C, CHK2 foci formation was assessed by immunofluorescent staining. Cells with five or more foci were counted as positive for staining. The percentage of cells with phosphorylated CHK2 foci was exhibited as the mean and standard deviation of triplicate counts of 100 cells.

Furthermore, we examined the foci formation of phosphorylated CHK2 on Thr 68 using immunofluorescent staining in CAOV3 cells after aphidicolin and irofulven treatment. The results demonstrated that phosphorylated CHK2 forms foci upon irofulven treatment (Fig. 4B), and CHK2 foci formation is reduced by aphidicolin treatment (Fig. 4C). Taken together, these results indicate that CHK2 activation induced by irofulven results from stalled DNA replication and is related to p53-mediated cell cycle arrest.

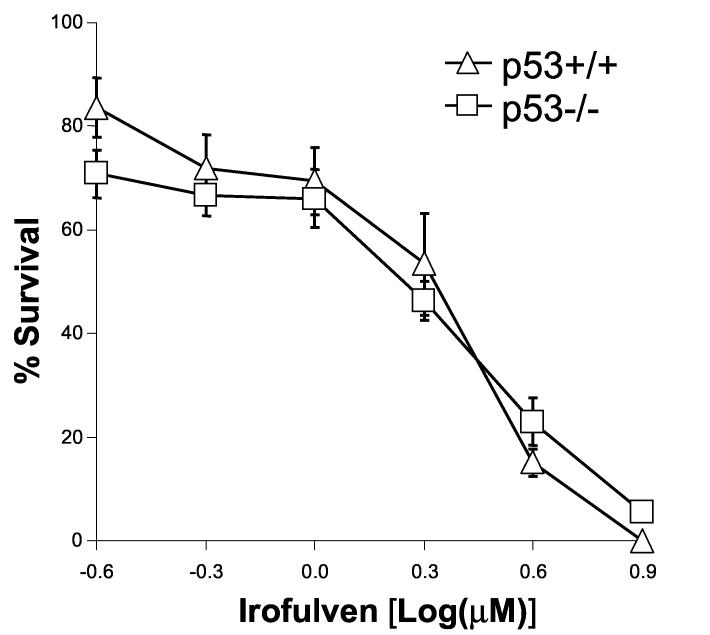

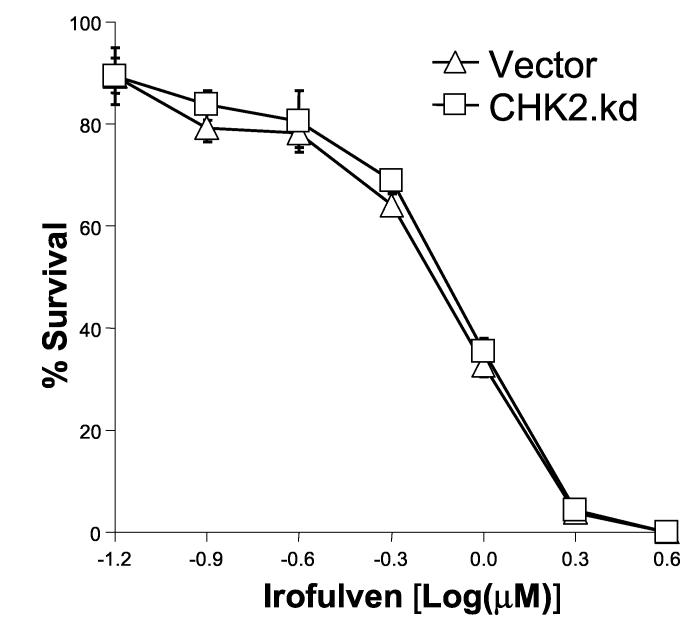

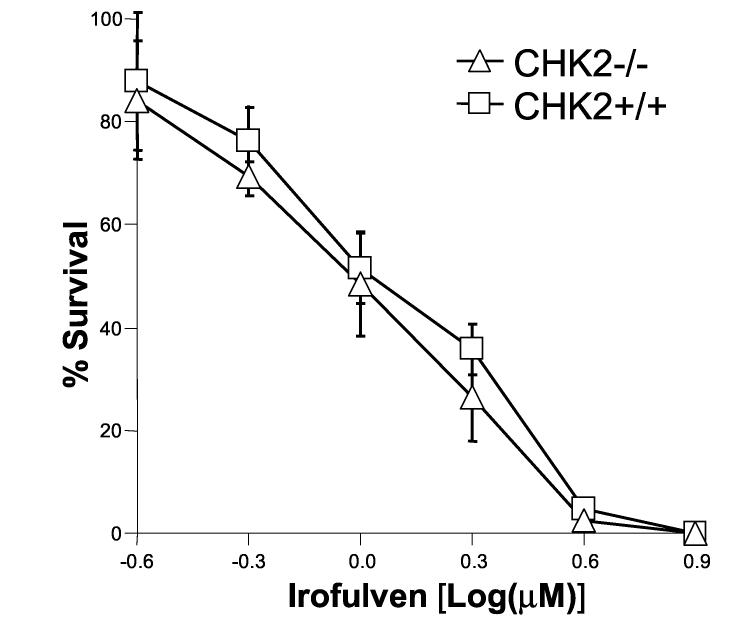

p53 or CHK2 activation does not contribute to chemosensitivity to irofulven

The activation and accumulation of p53 after irofulven treatment was observed (Fig. 2). Previous studies conducted in tumor cell lines with wild-type or mutant p53 suggested that the cytotoxicity induced by irofulven is independent of p53 status [55-57]. To confirm these results in an isogenic background, we performed clonogenic assay in HCT116 p53+/+ and p53−/− cells. The results indicated that p53 status does not affect chemosensitivity to irofulven (Fig. 5A).

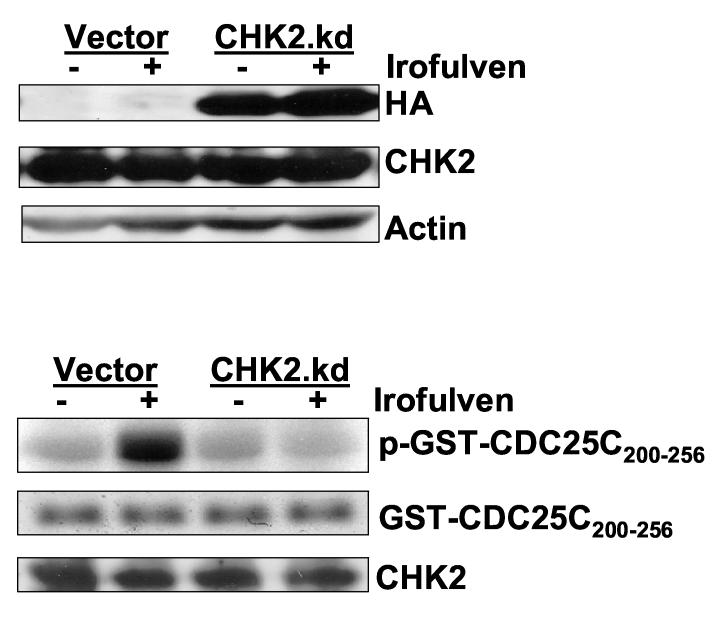

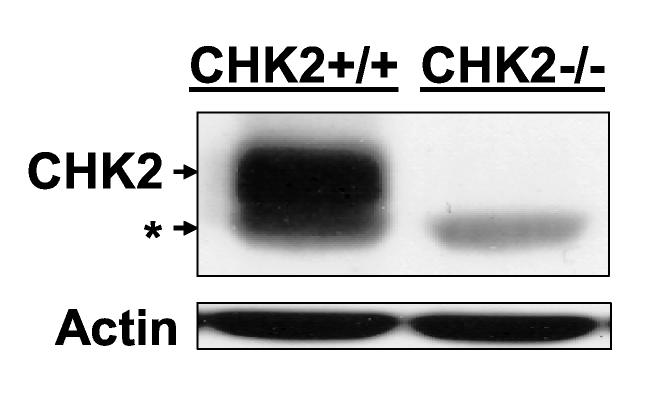

Fig. 5.

p53 or CHK2 activation does not contribute to chemosensitivity to irofulven. Cells were treated with irofulven for one hour followed by drug-free incubations. Irofulven-induced chemosensitivity was determined by clonogenic survival assay. The mean and standard deviation of triplicate experiments were presented. A, The clonogenic survival of HCT116 p53+/+ and p53−/− cells treated with irofulven. The p53 knock-out status of these cells was shown in Fig. 2D. B and C, Stable transfection of HA-tagged kinase-dead CHK2 (CHK2.kd) into CAOV3 cells. The vector and CHK2.kd-transfected CAOV3 cells were treated with 0.9 μM of irofulven for one hour followed by 24 hours of drug-free incubation. Western blot analyses were performed with antibodies against HA, CHK2 and actin (B). Immunoprecipitation and in vitro kinase assay were conducted with the antibody against CHK2 and with purified GST-CDC25C200-256 fusion protein as the substrate. The amounts of immunoprecipitated CHK2 and GST-CDC25C200-256 substrate in each reaction were verified by Western blot and Coommassie blue staining, respectively (C). D, The clonogenic survival of vector and CHK2.kd-transfected CAOV3 cells treated with irofulven. E, The CHK2 status in parental (HCT116 CHK2+/+) and CHK2-knockout (HCT116 CHK2−/−) cells was verified by Western blot analysis. The asterisk denotes a non-specific band. F, The clonogenic survival of HCT116 CHK2+/+ and CHK2−/− cells treated with irofulven.

Reports have been inconsistent regarding the role that CHK2 plays in apoptosis. To determine whether CHK2 activation modulates chemosensitivity to irofulven, we performed clonogenic survival assays in isogenic vector and dominant-negative CHK2-transfected CAOV3 cells, along with paired isogenic HCT116 CHK2+/+ and CHK2−/− cells.

First, we established stable CAOV3 cell lines expressing the HA-tagged dominant-negative CHK2 (CHK2 kinase-dead, CHK2.kd) [45]. The HA-CHK2.kd expression was verified by Western blot analysis with antibodies against HA and CHK2 (Fig. 5B). The effect of CHK2.kd in blocking endogenous CHK2 kinase activity was verified by immunoprecipitation and in vitro kinase assay with GST-CDC25C fusion protein as the substrate. As shown in Fig. 5C, the CHK2 kinase activity induced by irofulven was blocked by CHK2.kd expression. However, when the clonogenic survival assay was carried out in the cell lines, the results indicated that CHK2 did not contribute to irofulven-induced chemosensitivity (Fig. 5D).

To further confirm these findings, the paired, isogenic colon cancer cell line HCT116 CHK2+/+ and its CHK2-knockout cell line HCT116 CHK2−/− [44] were used. The CHK2 knockout status was verified by Western blot analysis (Fig. 5E). Clonogenic survival assay was performed and the results again demonstrated that CHK2 does not contribute to the chemosensitivity to irofulven (Fig. 5F).

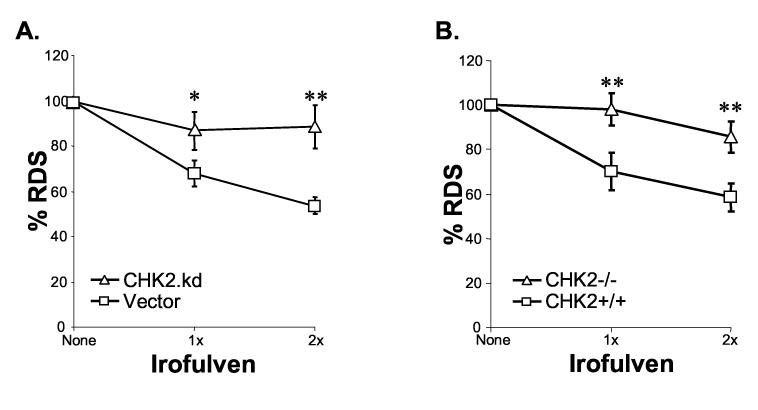

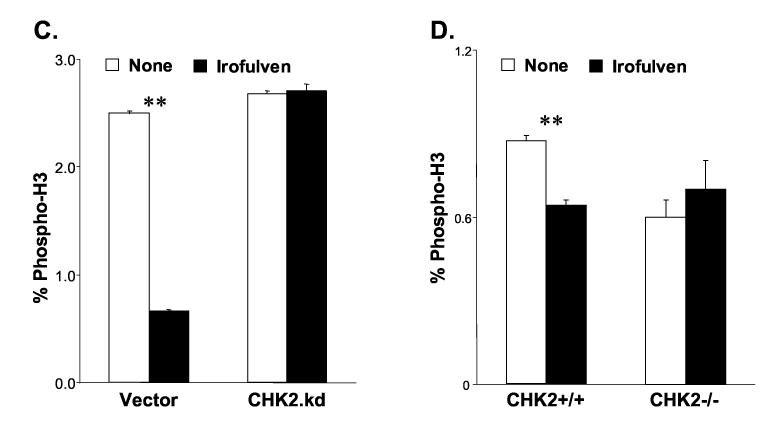

CHK2 activation contributes to the control of S and G2/M cell cycle arrest in response to irofulven-induced DNA damage

To explore the role that CHK2 activation plays in response to irofulven-induced DNA damage, we analyzed the alterations of cell cycle progression in CHK2.kd transfected cells and in CHK2-knockout cells. The radioresistant DNA synthesis (RDS) assay was performed to monitor the S phase checkpoint. The immunofluorescent staining for phospho-histone H3, a marker for mitosis, and FACS analysis were performed to assess the G2/M checkpoint.

The vector and CHK2.kd-transfected CAOV3 cells were treated with irofulven. The results of the RDS assay demonstrated that DNA synthesis was inhibited in vector-transfected CAOV3 cells after treatment compared with CHK2.kd-transfected cells (p<0.05 and p<0.01) (Fig. 6A). Similarly, when the DNA synthesis rate was assessed by RDS assay in isogenic HCT116 CHK2+/+ and CHK2−/− cells, more inhibition of DNA synthesis was observed in CHK2+/+ cells than in CHK2−/− cells after treatment (p<0.01) (Fig. 6B). These results indicate that CHK2 contributes to the control of S phase checkpoint in response to irofulven.

Fig. 6.

CHK2 activation contributes to the control of S and G2/M arrests after irofulven treatment. The statistical significance was analyzed by Student's t-test and marked as * (p<0.05) and ** (p<0.01). A and B, DNA synthesis was determined by RDS assay. The vector and CHK2.kd-transfected CAOV3 cells (A), and HCT116 CHK2+/+ and CHK2−/− cells (B) were treated with 1x or 2xIC50 concentration of irofulven for one hour followed by three hours of drug-free incubation. DNA synthesis rate was presented as the average and standard error of triplicate experiments. C and D, The mitotic population of cells was determined by immunofluorescent staining of phosphorylated histone H3 and flow cytometry. The vector and CHK2.kd-transfected CAOV3 cells (C), and HCT116 CHK2+/+ and CHK2−/− cells (D) were treated with 1xIC50 concentration of irofulven for one hour followed by one or three hours of drug-free incubation. The percentage of phospho-histone H3-positive cells was exhibited as the mean and standard deviation of triplicate experiments.

The results of FACS analysis of phospho-histone H3 staining demonstrated that one hour after treatment, phospho-histone H3-positive population decreased from 2.5% to 0.66% in vector-transfected CAOV3 cells (p<0.01); while in CHK2.kd-transfected CAOV3 cells, it was unchanged (Fig. 6C). When the phospho-histone H3-positive population was assessed in isogenic CHK2 knock-out cells three hours after treatment, it was decreased from 0.87% to 0.64% in CHK2+/+ cells (p<0.01); while in CHK2−/− cells, it was slightly increased from 0.6% to 0.7% (Fig. 6D). These results suggest that CHK2 controls the G2/M checkpoint in response to irofulven treatment.

Taken together, these results demonstrate that CHK2 contributes to the control of S and G2/M cell cycle arrests in response to irofulven-induced DNA damage.

4. Discussion

In this study, we found that CHK2 activation is replication-dependent and related to p53 status. p53 affects CHK2 activation by controlling cell cycle arrest and DNA replication in response to the anticancer agent, irofulven. CHK2 activation contributes to the control of cell cycle arrest, but not chemosensitivity.

Tumor suppressors p53 and CHK2 are frequently mutated in human cancers [5, 6]. Both p53 and CHK2 play important roles in cell cycle control, DNA repair and apoptosis [2, 5-26]. While many studies have investigated how CHK2 activates and stabilizes p53 [6, 17, 27-29], the possible role of p53 in regulating CHK2 protein level or activity has not been well studied. Studies conducted in tumor cell lines and tissue specimens have previously demonstrated an inverse correlation between p53 and CHK2 expression [30, 31]. However, in our previous and current studies, neither HCT116, HCT116 p53−/− nor p53 wild-type and mutant ovarian cancer cell lines demonstrated a dramatic inverse correlation of p53 and CHK2 protein levels after irofulven treatment [42]. Instead, we found that p53-deficient cells had enhanced CHK2 activation due to the loss of p53-regulated G1 arrest and stalled DNA replication in response to irofulven-induced DNA damage. In addition, we demonstrated that CHK2 activation contributes to the control of S and G2/M checkpoints. Therefore, enhanced CHK2 activation in p53-deficient cells serves as a mechanism to enforce cells arresting at S or G2/M phases in response to irofulven-induced DNA damage.

Previous studies conducted in tumor cell lines with wild-type or mutant p53 suggested that the cytotoxicity induced by irofulven is independent of p53 status [55-57]. In this study, the chemosensitivity to irofulven was compared in isogenic HCT116 p53+/+ and p53−/− cells. It was found that p53 status does not affect chemosensitivity to irofulven.

In mammalian cells, CHK2 was shown to promote DNA double-strand break repair via homologous recombination (HR) and non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ) by phosphorylating BRCA1 on serine 988 [10-13]. The CHK2 phosphorylation and nuclear foci formation observed in this study suggest that CHK2 was activated and recruited to the DNA damage sites, mediating the DNA repair process. CHK2 has also been implicated in regulating apoptosis [14-26]. However, there are some variations in the results reported. Some studies found that CHK2 is a negative regulator of mitotic catastrophe, and inhibition of CHK2 sensitizes cells to chemotherapy-induced apoptosis [14, 15]. One report suggested that CHK2 does not affect neuronal cell death induced by topoisomerase I or II inhibitors [20]. Other studies found that CHK2 is involved in apoptosis induction, however there is disagreement with regards to whether it is dependent or independent of p53 [16-23]. Given the diverse roles of CHK2 in DNA repair and apoptosis induction, whether CHK2 activation ultimately contributes to chemosensitivity was not evaluated in these studies. Here, we found that the loss or inhibition of CHK2 is not sufficient to render cancer cells more susceptible to irofulven treatment. CHK2 activation only contributes to the control of cell cycle arrests at S and G2/M phases in response to irofulven-induced DNA damage.

Recent reports have indicated that ATM and CHK2 are specifically activated by drug (calicheamicin) or radiation-induced DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs), and the level of activation directly correlates to the number of DNA DSBs [58, 59]. Our previous studies demonstrated that irofulven activates ATM and its targets, NBS1, SMC1, CHK2 and p53 [42]. In this study, we found that irofulven induces chromosome aberrations (breaks and radials), inhibits DNA replication and activates CHK2 in a replication-dependent manner. These data suggest that irofulven causes stalled DNA replication and the generation of DNA DSBs. Further studies are needed to elucidate the mechanisms that lead to stalled DNA replication, and whether proteins that are critical for the HR repair of DNA DSBs will modulate irofulven-induced chemosensitivity.

In summary, this study demonstrated that irofulven-induced CHK2 activation is replication-dependent and related to p53 status. p53 affects CHK2 activation by controlling cell cycle arrest and DNA replication. CHK2 activation contributes to the control of S and G2/M cell cycle arrests, but not chemosensitivity. Further characterization of irofulven-induced DNA damage and elucidation of the DNA damage signaling and repair pathways will allow a better understanding of the mechanisms of action involved with irofulven and improved application of this drug in the clinic.

5. Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Bert Vogelstein and Fred Bunz (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD) for generously providing colon cancer cell line HCT116 and its isogenic p53-knockout (HCT116 p53−/−) and CHK2-knockout (HCT116 CHK2−/−) cells; and thank Jann N. Sarkaria (Mayo Clinic and Foundation, Rochester, MN) for generously providing the HACHK2.kd and GST-CDC25C200-256 plasmids. We also thank Emily Van Laar for helpful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by NIH grant R03CA107979 (to W.W.).

Footnotes

This work was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (R03CA107979 to W.W.).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

6. References

- 1.Sherr CJ. The Pezcoller lecture: cancer cell cycles revisited. Cancer Res. 2000;60(14):3689–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou BB, Elledge SJ. The DNA damage response: putting checkpoints in perspective. Nature. 2000;408(6811):433–9. doi: 10.1038/35044005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abraham RT. Cell cycle checkpoint signaling through the ATM and ATR kinases. Genes Dev. 2001;15(17):2177–96. doi: 10.1101/gad.914401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shiloh Y. ATM and related protein kinases: safeguarding genome integrity. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3(3):155–68. doi: 10.1038/nrc1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levine AJ. p53, the cellular gatekeeper for growth and division. Cell. 1997;88(3):323–31. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81871-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bartek J, Lukas J. Chk1 and Chk2 kinases in checkpoint control and cancer. Cancer Cell. 2003;3(5):421–9. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00110-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cory S, Adams JM. The Bcl2 family: regulators of the cellular life-or-death switch. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2(9):647–56. doi: 10.1038/nrc883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vousden KH, Lu X. Live or let die: the cell's response to p53. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2(8):594–604. doi: 10.1038/nrc864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boddy MN, Shanahan P, McDonald WH, Lopez-Girona A, Noguchi E, Yates IJ, Russell P. Replication checkpoint kinase Cds1 regulates recombinational repair protein Rad60. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(16):5939–46. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.16.5939-5946.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang J, Willers H, Feng Z, Ghosh JC, Kim S, Weaver DT, Chung JH, Powell SN, Xia F. Chk2 phosphorylation of BRCA1 regulates DNA double-strand break repair. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24(2):708–18. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.2.708-718.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee JS, Collins KM, Brown AL, Lee CH, Chung JH. hCds1-mediated phosphorylation of BRCA1 regulates the DNA damage response. Nature. 2000;404(6774):201–4. doi: 10.1038/35004614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang HC, Chou WC, Shieh SY, Shen CY. Ataxia Telangiectasia Mutated and Checkpoint Kinase 2 Regulate BRCA1 to Promote the Fidelity of DNA End-Joining. Cancer Res. 2006;66(3):1391–400. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhuang J, Zhang J, Willers H, Wang H, Chung JH, van Gent DC, Hallahan DE, Powell SN, Xia F. Checkpoint Kinase 2-Mediated Phosphorylation of BRCA1 Regulates the Fidelity of Nonhomologous End-Joining. Cancer Res. 2006;66(3):1401–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Castedo M, Perfettini JL, Roumier T, Yakushijin K, Horne D, Medema R, Kroemer G. The cell cycle checkpoint kinase Chk2 is a negative regulator of mitotic catastrophe. Oncogene. 2004;23(25):4353–61. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Castedo M, Perfettini JL, Roumier T, Valent A, Raslova H, Yakushijin K, Horne D, Feunteun J, Lenoir G, Medema R, Vainchenker W, Kroemer G. Mitotic catastrophe constitutes a special case of apoptosis whose suppression entails aneuploidy. Oncogene. 2004;23(25):4362–70. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang S, Kuo C, Bisi JE, Kim MK. PML-dependent apoptosis after DNA damage is regulated by the checkpoint kinase hCds1/Chk2. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4(11):865–70. doi: 10.1038/ncb869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takai H, Naka K, Okada Y, Watanabe M, Harada N, Saito S, Anderson CW, Appella E, Nakanishi M, Suzuki H, Nagashima K, Sawa H, Ikeda K, Motoyama N. Chk2-deficient mice exhibit radioresistance and defective p53-mediated transcription. Embo J. 2002;21(19):5195–205. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirao A, Cheung A, Duncan G, Girard PM, Elia AJ, Wakeham A, Okada H, Sarkissian T, Wong JA, Sakai T, De Stanchina E, Bristow RG, Suda T, Lowe SW, Jeggo PA, Elledge SJ, Mak TW. Chk2 is a tumor suppressor that regulates apoptosis in both an ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM)-dependent and an ATM-independent manner. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22(18):6521–32. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.18.6521-6532.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jack MT, Woo RA, Hirao A, Cheung A, Mak TW, Lee PW. Chk2 is dispensable for p53-mediated G1 arrest but is required for a latent p53-mediated apoptotic response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(15):9825–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152053599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keramaris E, Hirao A, Slack RS, Mak TW, Park DS. ATM can regulate p53 and neuronal death independent of Chk2 in response to DNA damage. J Biol Chem. 2003 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304049200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brodsky MH, Weinert BT, Tsang G, Rong YS, McGinnis NM, Golic KG, Rio DC, Rubin GM. Drosophila melanogaster MNK/Chk2 and p53 regulate multiple DNA repair and apoptotic pathways following DNA damage. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24(3):1219–31. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.3.1219-1231.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu J, Xin S, Du W. Drosophila Chk2 is required for DNA damage-mediated cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. FEBS Lett. 2001;508(3):394–8. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)03103-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peters M, DeLuca C, Hirao A, Stambolic V, Potter J, Zhou L, Liepa J, Snow B, Arya S, Wong J, Bouchard D, Binari R, Manoukian AS, Mak TW. Chk2 regulates irradiation-induced, p53-mediated apoptosis in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(17):11305–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172382899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stevens C, Smith L, La Thangue NB. Chk2 activates E2F-1 in response to DNA damage. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5(5):401–9. doi: 10.1038/ncb974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stiewe T, Putzer BM. Role of the p53-homologue p73 in E2F1-induced apoptosis. Nat Genet. 2000;26(4):464–9. doi: 10.1038/82617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moroni MC, Hickman ES, Denchi EL, Caprara G, Colli E, Cecconi F, Muller H, Helin K. Apaf-1 is a transcriptional target for E2F and p53. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3(6):552–8. doi: 10.1038/35078527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chehab NH, Malikzay A, Appel M, Halazonetis TD. Chk2/hCds1 functions as a DNA damage checkpoint in G(1) by stabilizing p53. Genes Dev. 2000;14(3):278–88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shieh SY, Ahn J, Tamai K, Taya Y, Prives C. The human homologs of checkpoint kinases Chk1 and Cds1 (Chk2) phosphorylate p53 at multiple DNA damage-inducible sites. Genes Dev. 2000;14(3):289–300. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hirao A, Kong YY, Matsuoka S, Wakeham A, Ruland J, Yoshida H, Liu D, Elledge SJ, Mak TW. DNA damage-induced activation of p53 by the checkpoint kinase Chk2. Science. 2000;287(5459):1824–7. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5459.1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tominaga K, Morisaki H, Kaneko Y, Fujimoto A, Tanaka T, Ohtsubo M, Hirai M, Okayama H, Ikeda K, Nakanishi M. Role of human Cds1 (Chk2) kinase in DNA damage checkpoint and its regulation by p53. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(44):31463–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.44.31463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shigeishi H, Yokozaki H, Oue N, Kuniyasu H, Kondo T, Ishikawa T, Yasui W. Increased expression of CHK2 in human gastric carcinomas harboring p53 mutations. Int J Cancer. 2002;99(1):58–62. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matsui T, Katsuno Y, Inoue T, Fujita F, Joh T, Niida H, Murakami H, Itoh M, Nakanishi M. Negative Regulation of Chk2 Expression by p53 Is Dependent on the CCAAT-binding Transcription Factor NF-Y. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(24):25093–100. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403232200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.MacDonald JR, Muscoplat CC, Dexter DL, Mangold GL, Chen SF, Kelner MJ, McMorris TC, Von Hoff DD. Preclinical antitumor activity of 6-hydroxymethylacylfulvene, a semisynthetic derivative of the mushroom toxin illudin S. Cancer Res. 1997;57(2):279–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sato Y, Kashimoto S, MacDonald JR, Nakano K. In vivo antitumour efficacy of MGI-114 (6-hydroxymethylacylfulvene, HMAF) in various human tumour xenograft models including several lung and gastric tumours. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37(11):1419–28. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Friedman HS, Keir ST, Houghton PJ, Lawless AA, Bigner DD, Waters SJ. Activity of irofulven (6-hydroxymethylacylfulvene) in the treatment of glioblastoma multiforme-derived xenografts in athymic mice. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2001;48(5):413–6. doi: 10.1007/s002800100358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hidalgo M, Izbicka E, Eckhardt SG, MacDonald JR, Cerna C, Gomez L, Rowinsky EK, Weitman SD, Von Hoff DD. Antitumor activity of MGI 114 (6-hydroxymethylacylfulvene, HMAF), a semisynthetic derivative of illudin S, against adult and pediatric human tumor colony-forming units. Anticancer Drugs. 1999;10(9):837–44. doi: 10.1097/00001813-199910000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Britten CD, Hilsenbeck SG, Eckhardt SG, Marty J, Mangold G, MacDonald JR, Rowinsky EK, Von Hoff DD, Weitman S. Enhanced antitumor activity of 6-hydroxymethylacylfulvene in combination with irinotecan and 5-fluorouracil in the HT29 human colon tumor xenograft model. Cancer Res. 1999;59(5):1049–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Murgo A, Cannon DJ, Blatner G, Cheson BD. Clinical trials referral resource. Clinical trials of MGI-114. Oncology (Huntingt) 1999;13(2):233, 237–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kelner MJ, McMorris TC, Rojas RJ, Trani NA, Velasco TR, Estes LA, Suthipinijtham P. Enhanced antitumor activity of irofulven in combination with antimitotic agents. Invest New Drugs. 2002;20(3):271–9. doi: 10.1023/a:1016201807796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Senzer N, Arsenau J, Richards D, Berman B, MacDonald JR, Smith S. Irofulven demonstrates clinical activity against metastatic hormone-refractory prostate cancer in a phase 2 single-agent trial. Am J Clin Oncol. 2005;28(1):36–42. doi: 10.1097/01.coc.0000139019.17349.ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Woo MH, Peterson JK, Billups C, Liang H, Bjornsti MA, Houghton PJ. Enhanced antitumor activity of irofulven in combination with irinotecan in pediatric solid tumor xenograft models. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2005;55(5):411–9. doi: 10.1007/s00280-004-0902-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang J, Wiltshire T, Wang Y, Mikell C, Burks J, Cunningham C, Van Laar ES, Waters SJ, Reed E, Wang W. ATM-dependent CHK2 Activation Induced by Anticancer Agent, Irofulven. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(38):39584–92. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400015200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bunz F, Dutriaux A, Lengauer C, Waldman T, Zhou S, Brown JP, Sedivy JM, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Requirement for p53 and p21 to sustain G2 arrest after DNA damage. Science. 1998;282(5393):1497–501. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5393.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jallepalli PV, Lengauer C, Vogelstein B, Bunz F. The Chk2 tumor suppressor is not required for p53 responses in human cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2003 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M213159200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Busby EC, Leistritz DF, Abraham RT, Karnitz LM, Sarkaria JN. The radiosensitizing agent 7-hydroxystaurosporine (UCN-01) inhibits the DNA damage checkpoint kinase hChk1. Cancer Res. 2000;60(8):2108–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang W, Waters SJ, MacDonald JR, Roth C, Shentu S, Freeman J, Von Hoff DD, Miller AR. Irofulven (6-hydroxymethylacylfulvene, MGI 114)-induced apoptosis in human pancreatic cancer cells is mediated by ERK and JNK kinases. Anticancer Res. 2002;22(2A):559–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xu B, Kim S, Kastan MB. Involvement of Brca1 in S-phase and G(2)-phase checkpoints after ionizing irradiation. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21(10):3445–50. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.10.3445-3450.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Matsuoka S, Rotman G, Ogawa A, Shiloh Y, Tamai K, Elledge SJ. Ataxia telangiectasia-mutated phosphorylates Chk2 in vivo and in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(19):10389–94. doi: 10.1073/pnas.190030497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Melchionna R, Chen XB, Blasina A, McGowan CH. Threonine 68 is required for radiation-induced phosphorylation and activation of Cds1. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2(10):762–5. doi: 10.1038/35036406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ahn JY, Schwarz JK, Piwnica-Worms H, Canman CE. Threonine 68 phosphorylation by ataxia telangiectasia mutated is required for efficient activation of Chk2 in response to ionizing radiation. Cancer Res. 2000;60(21):5934–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee CH, Chung JH. The hCds1 (Chk2)-FHA domain is essential for a chain of phosphorylation events on hCds1 that is induced by ionizing radiation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(32):30537–41. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104414200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xu X, Tsvetkov LM, Stern DF. Chk2 activation and phosphorylation-dependent oligomerization. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22(12):4419–32. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.12.4419-4432.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ward IM, Wu X, Chen J. Threonine 68 of Chk2 is phosphorylated at sites of DNA strand breaks. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(51):47755–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100587200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huberman JA. New views of the biochemistry of eucaryotic DNA replication revealed by aphidicolin, an unusual inhibitor of DNA polymerase alpha. Cell. 1981;23(3):647–8. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90426-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Izbicka E, Davidson K, Lawrence R, Cote R, MacDonald JR, Von Hoff DD. Cytotoxic effects of MGI 114 are independent of tumor p53 or p21 expression. Anticancer Res. 1999;19(2A):1299–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Poindessous V, Koeppel F, Raymond E, Comisso M, Waters SJ, Larsen AK. Marked activity of irofulven toward human carcinoma cells: comparison with cisplatin and ecteinascidin. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9(7):2817–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Serova M, Calvo F, Lokiec F, Koeppel F, Poindessous V, Larsen AK, Laar ES, Waters SJ, Cvitkovic E, Raymond E. Characterizations of irofulven cytotoxicity in combination with cisplatin and oxaliplatin in human colon, breast, and ovarian cancer cells. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2006;57(4):491–9. doi: 10.1007/s00280-005-0063-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ismail IH, Nystrom S, Nygren J, Hammarsten O. Activation of ataxia telangiectasia mutated by DNA strand break-inducing agents correlates closely with the number of DNA double strand breaks. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(6):4649–55. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411588200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Buscemi G, Perego P, Carenini N, Nakanishi M, Chessa L, Chen J, Khanna K, Delia D. Activation of ATM and Chk2 kinases in relation to the amount of DNA strand breaks. Oncogene. 2004;23(46):7691–700. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]