Abstract

Context of case

In Portugal, the integration of care services is still in its infancy. Nevertheless, a home support service called SAD (Serviço de Apoio Domiciliário—Domiciliary Support Service), provided by non-profit institutions to the elderly population is believed to be a first approach to integrated care.

Purpose

The aim of this work is to describe and discuss the services provided by the institutions that participate in SAD and understand if this service is the first step in a change towards integrated care.

Data sources

The main data sources were documents provided by institutions like INE (Instituto Nacional de Estatística—National Institute of Statistics) and a questionnaire that was submitted to 75 institutions in order to capture: (a) demographic and structural data; (b) the type of information that the professionals need to fulfil their jobs and (c) the kind of relationship and constraints, if they exist, to better integration, between the institutions that provide SAD and the patients, the social and health systems, and other entities.

Conclusion and discussion

SAD seems to have been promoting a formal collaboration between several entities in the social and health systems. The information shared between these institutions has increased, but where cooperation in care service provision is concerned this seldom surpasses the social bounds because health care is still difficult to integrate.

Keywords: ageing, integrated care, Domiciliary Support Service, Portugal

Introduction

Portugal, as many other European countries, faces a growing elderly population, which increases the pressure on institutions and professionals to provide social and medical care in the most cost-effective way. The health and social care sectors in Portugal need a major reorganization effort and the concept of integrated care [1,2] emerges as a response to these challenges based on a coordinated work between independent institutions and professionals as a way to guarantee the continuity of care, improving health, quality of care and patient satisfaction, raising the efficiency and the effectiveness of social and health systems, and fostering patient's empowerment.

Integrated care may be defined as a well-planned and well-organized set of services and care processes, targeted at the multifaceted/multidimensional needs/problems of an individual client or group of persons with similar needs/problems. Integration is frequently seen as a cross-organizational integration of services, but tasks and services also have to be integrated within organizations. However, this type of integration is a more common management task, while integration across organizations and services is a relatively new issue for the professionals in the long-term care sector [3].

Integrated care can be conceived as client or consumer-driven care [2]. As such, it is not very different from innovations in industry, commercial services or other public sectors, such as education or public transport. In all these sectors, supply-driven management systems are gradually being replaced by integrated, demand/client-driven systems.

The integrated care approach is particularly relevant to patients with multiple and complex needs, such as the old and disabled, whose care in Portugal has been held to a great extent by social institutions [4] and encompasses complex interactions between different professionals and institutions.

In Portugal, like in most of the southern European Countries, the change in the paradigm is just starting and ‘care’, as it is understood in the northern European countries, is a relatively recent concept [5]. The investigation and practice of integrated care that has been gaining breadth in other European countries [6–8] is slowly getting to Portugal. The Programme of Integrated Support to the Elderly established in 1997 in Portugal (Programa de Apoio Integrado a Idosos—PAII) (Dispatch Collection no. 259/97 of 21st of August) has the following objectives:

ensuring the provision of care, including care of an urgent and permanent nature, trying to maintain the autonomy of the elderly in their own homes;

establishing the means to ensure the mobility of the elderly and their accessibility to appropriate benefits and services;

providing support to families taking care of dependent relatives;

promoting the training of professionals, volunteers, family members and other informal care providers;

setting measures to prevent isolation, exclusion and dependency and 6) to contribute to intergenerational solidarity as well as creating jobs [9]. On the other hand, the ‘national network of continued and integrated care’ (DL. 101/2006 of 06/06/2006) has been created recently.

In fact, the Portuguese healthcare system has a significant number of regulations, but few measures have been fully implemented. In terms of supply, there is a reasonable range of services and professionals to satisfy the needs of health and care services for the elderly. However, they are so dispersed and fragmented that accessibility and efficiency become compromised.

The health and care systems are facing several problems such as multiple entry points, inappropriate use of costly and scarce resources, waiting lists and a deficient transmission of information between institutions and professionals. Social and health institutions are among the most complex and interdependent institutions but they have remained separated for several reasons: different rules and jurisdictions, distinct budgets, different institutional and professional cultures and different approaches in the provision of care.

Nevertheless, a home support service called SAD [10] provided by non-profit institutions to the dependent population, is believed to be a first approach to integrated care. It aims at improving the quality of life of patients and their families and avoiding or delaying institutionalization, keeping the patients in their homes and in their usual social environment. The specific objectives of SAD include: satisfying patients basic needs, providing physical and social support to the individuals and their families, and collaborating in health care provision. Therefore, SAD planning, structuring and operating clearly offers many opportunities for integration between several care providers.

The integration of care encompasses many aspects that must be planned and implemented at different levels. Integration may impact significantly on one or several organizations' structures, people, cultures, strategies, management and information systems, but some may remain unchanged. However, the effort must inevitably translate into one aspect, communication among parties, if results are to be achieved. Silber states that there is no quality health care without a proper management of information and its flow [11]. In a context of integration, the challenge begins earlier and materializes in formal and informal communication.

The paper unfolds as follows: first, we show how health and social care evolved through time, from an integrated approach to separated systems, describing the historical development of the Portuguese health care system and its financing and discussing the offering of social care in Portugal, namely SAD. Next, we present the data and discuss the results.

Context of case

The historical development and financing of the Portuguese health care system

Before the eighteenth century, health care was provided only to the poor by hospitals and religious charities (Misericórdias). The development of public health services started in 1901 with the start of a network of medical officers responsible for public health. In 1945, a public law established public maternity and child welfare services, as well as national programmes for tuberculosis, leprosy and mental health.

In 1946, a mandatory social health insurance system was created, Caixas de Previdência, which provided cover to the employed population and their dependants through social security and sickness funds. This system was financed by contributions of employees and employers and provided out-of-hospital curative services, free at the point of use.

The Democratic Revolution occurred on 1975 ending a long period of political dictatorship and a process of health services nationalization began, aiming to give the whole population access to healthcare, independent of their ability to pay. In 1979, the National Health Service (NHS) was created as a universal system, free at the point of use. In fact, until 1979 the Portuguese State had left the responsibility for paying for health care to the individual patient and his/her family. The care of the poor was the responsibility of charity hospitals and the Department of Social Welfare was responsible for the out-of-hospital care.

After 1974, district and central hospitals owned by the religious charities were taken over by the State, as well as 2000 medical units or health posts across the country, which previously operated under the social welfare system for the exclusive use of social welfare beneficiaries and their families. The public health services and the health services provided by social welfare were brought together, leaving the general social security system to provide cash benefits and other social services for namely the elderly and children.

The 1979, legislation established the right of all citizens to health protection, access to the NHS for all citizens, integrated health care including health promotion, disease surveillance and prevention and a tax-financed system of coverage in the form of the NHS [12].

Since then, a number of reforms have been carried out. In 2002 a framework for the implementation of public/private partnerships aiming at building, maintaining and operating the health facilities was created. A Decree established the obligation of NHS drugs prescription using the common international denomination, as well as the conditions under which prescribed brands can be substituted by generics. Around 40% of all NHS hospitals were transformed into public enterprises.

However, in the twenty-first century, the health care system in Portugal still faces many problems such as inadequate ambulatory services, long waiting lists, dissatisfaction of consumers and professionals, increasing expenditures with health and increasing demand for health care from vulnerable groups.

NHS is mainly financed by general taxes. A soft budget for total NHS expenditures is established within the annual national budget. However, actual health expenditures usually exceed the budget limits, requiring the approval of supplementary budgets.

The health subsystems account for around 5% of total health expenditure and are normally financed through employer and employee contributions. These contributions are often insufficient to cover the full costs of care, which are in a significant part shifted onto the NHS.

There are other complementary sources of financing such as the ‘voluntary health insurance’, which has been taken out by approximately 10% of the population, as well as the ‘mutual funds’, which cover around 7% of the population. The ‘mutual funds’ voluntary contributions are managed by non-profit organizations that provide limited cover for consultations, drugs and some inpatient care.

In recent years, there has been increasing use of co-payments in health care with the aim of making consumers more cost-aware, which have accounted for over 30% of total health expenditure over the last ten years.

The social care

In Portugal, there is an insufficient provision of community care services, including long term care and social services for the chronically ill, the elderly and other groups with special needs. In fact, the family has been assuming the first line of care, particularly in rural areas. Yet, the demographic pressures demand new solutions in what refers to the provision of social care.

Some social services are provided in each region through the Ministry of Social Security. However, IPSS (Instituições Particulares de Solidariedade Social), which are non-profit non-public institutions for social solidarity, and among them Misericórdias have been the main providers of these services, namely meals activities, laundry services and assistance obtaining medication or health care.

According to the Law no 119/83 of 25 of February (IPSS statutes): “these are non-profit and non-public institutions whose main purpose is to provide social support to necessitous persons but also to promote education and prevention of diseases”.

The government recognises the relevance of IPSS in the provision of social services to the population through the establishment of cooperation and financial agreements. In fact, the family support has been decreasing and the State considers the IPSS a strategic part in the care system.

Compared to the residential care provided by the public sector, the nursing homes run by Misericórdias and other non-profit institutions are usually of better quality and only request a nominal contribution from patients and their families. Nursing homes in the private sector are very expensive and the majority of the population cannot pay for them.

Home care is expanding in Portugal and in some regions infrastructures to deliver support to the elderly have been developed in partnership with municipalities, regional health administrations and non-profit institutions. Apparently, the establishment of social care networks is becoming a priority.

SAD is a social response that consists of the provision of individualized care in the patients' home when they cannot assure temporarily or permanently the satisfaction of their basic needs and their daily activities. SAD is a recent service, designed to give domiciliary support on the social sphere and collaborate on the provision of health care by IPSS to maintain people in their usual social environment, close to their families, neighbours and friends [10,13]. Its big impulse was between 1986 and 1995 with an average opening of 75 new facilities per year. In the second half of the 1990s, SAD spread all over the country, with an average opening of 122.3 new facilities per year.

SAD must provide the following services: hygiene and comfort in the home, nursing, transportation, meal delivery and laundry. However, it can also cover other needs such as buying essentials, accompanying to social activities and doing little repairs. The bodies involved in SAD are patients, IPSS, health centres, physicians, municipalities and other entities.

In the year 2000, SAD in Portugal was characterized as follows [14]:

a homogeneous distribution with the most populous regions having more than 100 institutions providing the service;

a covering rate around 2.64%; services required mostly by elderly over 74 years old, with a percentage of women of 57%;

93% of providers having agreements with Social Security;

6% of providers having rehabilitation services

5.7% of providers having night service.

The services available are identified in Table 1 [14].

Table 1.

Activities concerning SAD in the year 2000

| Service | Providers (%) |

|---|---|

| Transportation and delivering meals | 98 |

| Hygiene and comfort | 97 |

| Laundry | 95 |

| Tidy up and cleaning | 93 |

| Collaboration with health services | 78 |

| Accompanying to social activities, consultations… | 72 |

| Leisure activities | 62 |

| Shopping | 60 |

Case description: SAD in the district of Aveiro

The framework

The main purpose of this study is to analyze SAD in Portugal and specifically in the district of Aveiro and to understand if it is the first step towards integrated care. The analysis refers to the number and capacity of institutions that provide SAD, the type of services provided, demographic data, the kind of relation between all the parties and the cooperation and communication level.

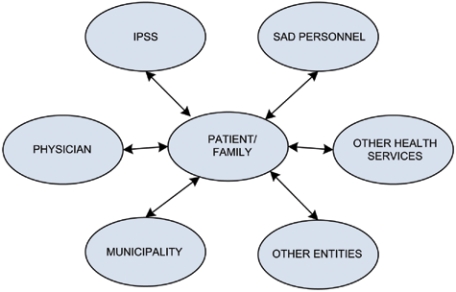

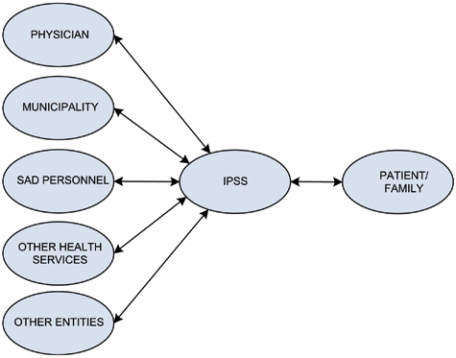

At present, the interactions between the parties committed to SAD are as described in Figure 1. In the future, it is expected that a model will emerge in which the IPSS acts as a link between the patient/families and the other parties, fostering the sharing of patient information and improving the quality in the provision of care (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

The actual interactions between the parties committed to SAD.

Figure 2.

The model that is expected to emerge in the near future.

Data source

The data on which this work is based came from the analysis of documents provided by institutions like INE and from a questionnaire submitted to 75 institutions to capture: (a) demographic and structural data; (b) the type of information that the professionals need to fulfil their jobs; and (c) the kind of relationship and constraints, if they exist, between the institutions that provide SAD and the patients, the social and health systems and the local authorities. The conditions in the District were thought to be appropriated to this study but the results have to be interpreted with caution concerning representativeness and cannot be generalized to the country.

The questionnaire was submitted to 75 institutions that provide SAD (63% of the total) previous to being piloted in two different institutions, in order to be adapted and ameliorated. Among the 75 institutions, 45 were surveyed by telephone and 30 by e-mail.

Data analysis and results

In the year 2000, the number of IPSS registered in Portugal with social purposes was around 3000 and the total number of IPSS's elderly patients was 136,639. The social protection to the elderly represented 31.8% of all of the IPSS's activities in 2000 and 33.8% in 1998 (Table 2).

Table 2.

IPSS's activities (INE, 2001)

| Year | Total | Family (%) | Old (%) | Disease (%) | Social exclusion (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 100.0 | 44.1 | 31.8 | 21.6 | 2.5 |

| 1999 | 100.0 | 44.4 | 31.1 | 21.7 | 3 |

| 1998 | 100.0 | 43.5 | 33.8 | 20 | 2.7 |

According to the Social Security there are 248 IPSSs in Aveiro and 48% of them provide SAD. The total capacity of these IPSSs is 3489 users. The elderly population is estimated to be 103,848 citizens [15], which means that the IPSSs in Aveiro can only provide services to 3, 4% of the elderly population in the region. Only 2, 7% make use of SAD, which corresponds to 80% of the capacity of the IPSSs. However, while some institutions in some municipalities have extra capacity, in others, all the resources are being used. Except for one municipality, we can say that the District doesn't seem to lack capacity with regard to the provision of this service.

The enquiries were conducted along with directors (45%), case workers (29%) and other professionals (26%). Concerning human resources, 1% of the institutions have less than 10 employees, 43% have between 10 and 30 employees, 22% have between 31 and 50 and 30% have more than 50.

The majority of the IPSSs (84%) provides SAD daily (including weekends), in comparison to 16% of the institutions that only offer this service on Mondays. SAD can be provided not only to the elderly but also to people with special needs: 100% of the IPSSs provide SAD to the elderly, 76% of the institutions provide SAD to everyone who needs this service (elderly, ill, disabled), 12% exclusively to the elderly, 8% to the elderly and the disabled and 4% to the elderly and the ill.

Usually it is the family who contacts the IPSS when there is an interest in SAD. The family is responsible for 46% of the contact with the IPSS, followed by health institutions (21%), the user (20%), the Social Security (8%) and neighbours (5%).

The main reason (74% of the cases) for appealing to SAD is the user's real need of this service, while a lower percentage (15%) of the cases want to benefit from other services offered by the IPSS (11% didn't answer this question).

With regard to the abilities of the professionals involved in SAD, 55% of the IPSSs require professionals with specific qualifications, while 45% of the cases don't. However, 76% of the IPSSs provide specific training, against 24% who don't.

The institutions involved in SAD, other than the IPSSs, are:

the Social Security, who maintains a formal partnership with the IPSSs and pays a contribution per patient;

some health institutions, but in only 25.6% of the cases is there a formal relationship;

the Municipalities (21.5%);

other entities (20%). In the case of these last two parties, the relations are strictly informal.

The communication between the professionals involved in SAD is considered easy for 61% of the interviewees, and 43% of the personnel classify the availability of information as good, 41% as regular, 10% as very good, 3% as bad and 3% as very bad.

The means of contact between the IPSSs and the patient or someone responsible for the patient are: exclusively the domiciliary visit made by the case worker (44%); only by telephone (1%); through domiciliary visits and telephone (55%).

The frequency of contact between the case worker and the patient can be summarized as follows: 33% have weekly contact with the patient; 33% whenever is necessary; 16% monthly; 15% twice a month; and 3% gave no response. On a daily basis, there is contact between SAD workers and the patient, and important information can be communicated to the case worker.

With regard to the type and quality of services, the interviewee's perceptions are resumed in Table 3. The percentage of institutions providing the different services seems to be in line with the results of previous national studies [13]. From our work, we can conclude that collaboration with the health services has to be reinforced.

Table 3.

Perceptions concerning the type and quality of services provided

| Type of services provided in SAD | Provide this kind of service (%) | Very bad (%) | Bad (%) | Neither good nor bad (%) | Good (%) | Very good (%) | No answers (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hygiene and comfort | 100 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 59 | 35 | 1 |

| Nursing | 35 | 20 | 9 | 14 | 26 | 7 | 24 |

| Physiotherapy | 8 | 34 | 7 | 9 | 8 | 5 | 37 |

| Tidy up and cleaning | 97 | 3 | 3 | 26 | 38 | 27 | 3 |

| Meals delivery | 100 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 49 | 46 | 1 |

| Doing the laundry | 94.6 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 49 | 41 | 1 |

| Accompanying to medical consultations | 73 | 7 | 5 | 30 | 34 | 15 | 9 |

| Buying essentials | 75.5 | 5 | 3 | 26 | 47 | 11 | 8 |

| Accompanying to social activities | 74.5 | 8 | 5 | 24 | 39 | 15 | 9 |

Physiotherapy and nursing support are provided in the health centres because most of the IPSSs do not have the necessary resources.

All the interviewees considered the family the most relevant element in the system that support SAD, followed by the neighbours (53%), friends (26%) and volunteers (21%).

With respect to quality control and assessment mechanisms of SAD, 96% of the IPPSs apply questionnaires or have informal conversations with the patients to measure their satisfaction level and consequently the quality degree of the services provided. The person responsible for this quality control is a social worker or a director. Only 4% of the IPSSs included in this study do not make this type of evaluation.

Regarding the accessibility of financial resources to provide this service, 46% of the interviewees evaluate the situation as regular, 31% as good, 14% as bad, 4% as very good and 5% as very bad.

Discussion and conclusion

Portugal, as most countries, has a fast growing elderly population that demands a deep analysis on the adjustment of the care system that is at present very fragmented.

Socio-demographic trends demand new approaches in the provision of care such as the integrated care concept to promote the continuity of care and the reduction of inefficiencies and redundancies, which implies a change in the professionals' culture and a redesign of the care system itself.

SAD, a domiciliary service offered to frail and dependent persons, was believed to be a first approach to integration. However, in respect to SAD in Aveiro, the majority of the institutions that provide this service do not work in an integrated way. The integration of care exists only formally with the Social Security and rarely with some health centres. Even with respect to the communication between the professionals involved with SAD, which is considered to be easy and good, the use of communication technology is restricted to the use of telephone as well as computers, where some records on the patients are stored but not shared between institutions.

The care services provided are mainly of a social nature which is obviously the consequence of a lack of resources and competencies necessary to deliver health care. Only 8% of the institutions offer a physiotherapy service and in almost half of the cases, the service is evaluated as bad or very bad. Nursing is provided in 35% of the cases, but in 29% it is evaluated as bad or very bad by the professionals. The percentage of no answers is high, mirroring some difficulties in evaluating these kinds of services, provided by other entities. In 73% of the institutions, the patients have access to a service of being escorted to medical consultations.

The word integrated describes a characteristic of structures and processes. It implies that actors (members) and activities (functions) are relatively highly connected, interdependent and functioning to achieve common goals. Integration always implies the inclusion of certain actors and activities and the exclusion of others. Thus, it makes a distinction between the system and the environment [16].

The extension of these institution's boundaries is believed to be conditioned by a number of political, structural, individual, social and cultural aspects, which need to be identified and managed. The integrated care concept requires major efforts concerning communication between parties and the building of a shared vision between scientists, politicians and practitioners. These parties also need to recognize important interdependencies, learn how to work as a team, as well as mitigate some professional and institutional boundaries [17].

The health and social systems, although interdependent, are divided because they have different goals and rules, inter-sectoral boundaries and professional and cultural differences. As a consequence, the provision of care is fragmented, discontinuous and inefficient. Vulnerable individuals, like the elderly, require a mix of services delivered sequentially or simultaneously by multiple providers and receiving care at home, in the community and in institutional settings. That is why it is so important to find innovative ways to get around these gaps. However, there are several barriers to this effort that must be further investigated and surpassed.

Based on analyses performed on the various systems in EU member states in the context of the CARMEN Project [3], managers in these countries face many of the same obstacles:

insufficient public funding to provide sufficient services;

non-corresponding funding and legislative systems;

unequal access;

unbalanced systems;

system's complexity;

responsibility as a barrier to decision-making;

interface problems;

supply driven systems;

human resources;

non-responding cultures;

quality management and integration becoming an end in itself.

The analysis [3] also states that sometimes the obstacles are used merely as an excuse for non-collaboration.

Contributor Information

Silvina Santana, Department of Economics, Management and Industrial Engineering, University of Aveiro, Portugal.

Ana Dias, IEETA- Institute of Electronics Engineering and Telematics of Aveiro, Portugal.

Elisabete Souza, Department of Economics, Management and Industrial Engineering, University of Aveiro, Portugal.

Nelson Rocha, Department of Health Sciences, University of Aveiro/IEETA, Portugal.

Reviewers

Jenny Billings, Research Fellow, Centre for Health Services Studies, University of Kent, Canterbury, United Kingdom.

Leonor Cardoso, PhD, Teacher of Work and Organizational Psychology Faculty of Psychology and Education Sciences University of Coimbra, Portugal.

One anonymous reviewer.

References

- 1.Gröne O, Barbero M. Trends in integrated care—reflections on conceptual issues [Online] 2002 Available from: URL: http://www.euro.who.int/document/ihb/Trendicreflconissue.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kodner D, Spreeuwenberg C. Integrated care: meaning, logic, applications, and implications—a discussion paper. International Journal of Integrated Care [serial online] 2002 Nov 14;2 doi: 10.5334/ijic.67. Available from: URL: www.ijic.org. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nies H. Integrated care: concepts and background. In: Integrating Services for Older People: a resource book for managers [Online] EHMA Online Publications 2004. 2004:18–32. Available from: URL: http://www.ehma.org/_fileupload/Publications/IntegratingServicesfoOlderPeopleAResourceBookforManagers.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hespanha P. Entre o Estado e o Mercado: as fragilidades das instituições de protecção social em Portugal. [Between Government and the Market: the fragilities of social protection institutions in Portugal]. Coimbra: Quarteto Editora; 2000. [in Portuguese] [Google Scholar]

- 5.SeniorWatch. European SeniorWatch Observatory and Inventory: a market study about the specific IST needs of older and disabled people to guide industry, RTD and policy: WP 4 Country Reports-Portugal [Online] 2002. May, Available from: URL: http://www.empirica.biz/swa/

- 6.Alaszewski A, Billings J, Baldock J, Coxon K, Twigg J. Providing integrated health and social care for older persons in the United Kingdom. Centre for Health Services Studies, University of Kent Canterbury; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leichsenring K. Providing integrated health and social care for older persons—a European overview [Online] European Centre for Social Welfare Policy and Research; 2003. Jun, Available from: URL: http://www.imsersomayores.csic.es/documentos/documentos/procare-providingeurope-01.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raak AV, Mur-Veeman I, Hardy B, Steenbergen M, Paulus A. Integrated care in Europe: description and comparison of integrated care in six EU countries. Maarssen (NL): Elsevier gezondheidszorg; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ministério da Saúde [Ministry of Health] National Health Programme for the elderlyPrograma nacional para a saúde das pessoas idosas. Despacho Ministerial de 08-06-2004; 2004. [in Portuguese]

- 10.Bonfim C, Veiga S. Serviços de apoio domiciliário. [Domiciliary Support Services]. Lisboa: Direcção Geral da Acção Social, Núcleo de Documentação Técnica e Divulgação; 1996 [in Portuguese]; [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silber D. The case for e-Health. Presented at the European Commission's first high-level conference on e-Health, May 22/23 2003 [Online] Maastricht (NL): European institute of Public Administration; 2003. Available from: URL: http://europa.eu.int/information_society/eeurope/ehealth/conference/2003/doc/the_case_for_eHealth.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bentes M, Dias C, Sakellarides C, Bankauskaite V. Health care systems in transition: Portugal [Online] Copenhagen: European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2004. Available from: URL: http://www.euro.who.int/document/e82937.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bonfim C. População idosa, análise e perspectivas: a problemática dos cuidados intra familiares. [Old population, analysis and perspectives: the problems of intra family care]. Lisboa: Direcção Geral da Acção Social, Núcleo de Documentação Técnica e Divulgação; 1996. [in Portuguese] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacob L. Os serviços para idosos em Portugal. [The services for the elderly in Portugal]. Lisboa: ISCTE; 2004. Msc dissertation. [in Portuguese] [Google Scholar]

- 15.INE AND II Assembleia Mundial sobre o Envelhecimento [World-Wide Assemby on ageing] O envelhecimento em Portugal: situação demográfica e sócio-económica recente das pessoas idosas. 2002. Available from: URL: http://alea-estp.ine.pt/html/actual/pdf/actualidades_29.pdf [in Portuguese]

- 16.Pieper R. In: Integrating Services for Older People: a resource book for managers [Online] EHMA Online Publications, 2004; 2004. Integrated Organisational Structures; pp. 33–54. Available from: URL: http://www.ehma.org/_fileupload/Publications/IntegratingServicesfoOlderPeopleAResourceBookforManagers.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dias A. A mudança do paradigma e a adopção de TIC em instituições prestadoras de cuidados. [The change of paradigm and the ICT adoption process in care provision institutions]. Aveiro: Univerity of Aveiro; 2005. Msc Dissertation. [in Portuguese] [Google Scholar]