Abstract

Questionnaires were mailed to veterinarians in western Canada to determine dog and cat deworming protocols and the association between perceived zoonotic risk and perceived prevalence of endoparasites and deworming protocols. Of the responding veterinarians (545), 13% and 39% recommended deworming protocols consistent with established guidelines for puppies and kittens, respectively. Mixed animal practitioners and high-perceived prevalence of Toxocara cati were associated with increased appropriate kitten deworming (P < 0.01 and P = 0.04, respectively). High-perceived zoonotic concern of Toxocara canis was associated with increased appropriate puppy deworming (P = 0.01). Sixty-eight percent of veterinarians noted an established hospital deworming protocol, although only 78% followed the protocol. Forty-four percent of veterinarians stated they discussed with all clients the zoonotic risk of animal-derived endoparasites, whereas the remainder discussed it only under particular circumstances or not at all. Most small animal deworming protocols recommended in western Canada begin too late to inhibit endoparasite shedding. Increased educational efforts directed at veterinarians are warranted.

Résumé

Protocoles de vermifugation chez les petits animaux, éducation des clients et perception de l’importance des parasites zoonotiques par les vétérinaires de l’ouest du Canada. Des questionnaires ont été postés à des vétérinaires de l’ouest du Canada afin d’établir des protocoles de vermifugation chez les chiens et les chats et de déterminer l’association entre le risque zoonotique perçu, la perception de la prévalence des endoparasites et les protocoles de vermifugation. Sur les 545 vétérinaires répondants, 13 % et 39 % ont respectivement recommandé des protocoles de vermifugation compatibles avec les normes établies pour les chiots et les chatons. Les vétérinaires de pratique mixte et une perception élevée de la prévalence de Toxocara cati étaient associés à une augmentation des pratiques appropriées de vermifugation (P < 0,01 et P = 0,04, respectivement). Une préoccupation zoonotique élevée de Toxocara canis était associée à une augmentation de protocoles appropriés de vermifugation des chiots (P = 0,01). Soixante-huit pour cent des vétérinaires inscrivaient un protocole de vermifugation établi par l’hôpital alors que seulement 78 % le suivaient. Quarante-quatre pour cent des vétérinaires mentionnaient qu’ils discutaient des risques zoonotiques reliés aux endoparasites des animaux avec leurs clients alors que les autres en discutaient uniquement lors de circonstances particulières ou pas du tout. La majorité mentionnait que les protocoles de vermifugation des petits animaux utilisés dans l’ouest du Canada commençaient trop tard pour éviter l’excrétion des endoparasites. De plus grands efforts d’éducation à l’intention des vétérinaires sont justifiés.

(Traduit par Docteur André Blouin)

Introduction

Endoparasites are commonly encountered in small animal veterinary medicine (1). Reports of endoparasite prevalence in domestic small animals range from 5% to 70% worldwide (1–7), with similar findings in Canada (8–12, unpublished data — Stull, 2003); differences in study location, year conducted, status of animal ownership, and methodology are responsible for the wide range in published endoparasite prevalence. Clinical signs in infected animals vary from none (13,14) to severe (fatal anemia, emaciation). The life cycles of endoparasites commonly encountered early in life, such as Toxocara canis (15,16), Toxocara cati (17), and Ancylostoma caninum (16) are well documented. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (18) recommends treatments at 2, 4, 6, and 8 wk of age for puppies and 3, 5, 7, and 9 wk of age for kittens to prevent establishment of T. canis, T. cati, and A. caninum infections. Given a relatively lower risk of acquisition of roundworms and hookworms in kittens than in puppies, 6 wk of age has been noted as an acceptable age for commencing deworming in kittens (19). Concurrent treatment of the bitch every 2 wk during the 8-week postwhelping period is important to eliminate reactivated larvae (20) and horizontal transmission from shedding neonates (21). Prophylactic treatment is recommended during the postwhelping/neonatal time period, since negative fecal examinations may be misleading. Regular treatment/screening for endoparasites is warranted, because repeated infection can occur throughout life (22). Similar neonate and adult deworming guidelines are endorsed by the Companion Animal Parasite Council (23).

In addition to the hazards endoparasites pose to the animal community, humans can be infected. Manifestations of these zoonotic diseases vary with the causative agent, but include visual (24), neurologic (25), dermatologic (26), respiratory (27), and enteric disorders (28), all of which have a dramatic impact on human health and the economy (29). Seroprevalence studies have documented substantial exposure to Toxocara in Canadians (30–32); however, as neither this disease nor its associated syndromes (visceral larval migrans — VLM, ocular larval migrans — OLM) are reportable by law, it is difficult to determine the true incidence in the population. Estimates suggest 10 000 cases of VLM and 700 cases of OLM occur each year in the United States (29). Several factors predispose humans to zoonotic transmission, including pica (25), dog ownership/contact (24,25,33), socio-economic status, and geographic location (34).

Despite the high prevalence of zoonotic endoparasites in domestic small animals, the significant public health risk they pose, and ease of parasite removal through appropriate deworming protocols, previous studies have indicated poor veterinary compliance in applying appropriate deworming protocols (35–37). Although some studies have examined small animal deworming protocols, veterinarian-perceived parasite prevalence (37), and perceived zoonotic risk (37,38), it is not entirely understood why poor deworming-compliance persists and how to correct it. Previous studies examining deworming protocols were limited geographically (37) and temporally (35,36), so it cannot be assumed that the findings from these studies are valid today in other locations. Furthermore, although studies have examined veterinarian-perceived risk and veterinarian-perceived prevalence of various endoparasites, none has determined their association with recommended deworming protocols. Attaining a better understanding of current deworming practices and potential risk factors for deviation from an appropriate protocol will enable targeted education of the veterinary community and aid in the identification of further areas of research.

The objective of this study was to utilize questionnaires mailed to all small and mixed animal veterinarians in western Canada to determine current recommended small animal deworming protocols and to compare these protocols with established guidelines. Data were collected on veterinarian-perceived prevalence and veterinarian-perceived zoonotic concern of several endoparasites to determine if associations existed between recommended deworming protocols, client education, and veterinarian perceptions.

Materials and methods

In order to examine current recommended small animal deworming protocols and the association between veterinarian-perceived zoonotic risk, veterinarian-perceived prevalence of endoparasites, and deworming protocols, a questionnaire was mailed to all small and mixed animal veterinarians practicing in western Canada.

Selection of study sample

In January 2003, all practicing veterinarians coded in the Canadian Veterinary Medical Association (CVMA) database as small or mixed animal practitioners, residing in British Columbia (BC), Alberta (AB), Saskatchewan (SK), or Manitoba (MB), (n = 2145) were mailed a cover letter, questionnaire, and postage-paid return envelope. In these provinces all practicing veterinarians are automatically members of the CVMA. Questionnaires returned before August 2003 were eligible for inclusion in the study. No attempt was made to follow-up nonrespondents.

Survey questionnaire

The questionnaire consisted of 4 sections: 1) demographic information, 2) recommended deworming protocols, 3) client education, and 4) frequency of diagnosis and zoonotic concern of specific parasites. Demographic information was obtained through questions regarding number of years in practice, type of practitioner (small or mixed animal), number of veterinarians at their current clinic, and number of small animals they examined each week. Information pertaining to deworming protocols and client education was obtained by asking the following questions: 1) “what age do you routinely first see puppies/kittens”, “when do you recommend deworming puppies — place a check next to all ages” (week intervals were provided for ages 1–16 wk and month intervals were provided for 5–12 mo), or “never,” or “as needed based on fecal examination;” 2) “when do you recommend deworming adult dogs” (The same deworming questions were asked for kittens/cats); 3) “do you recommend routine deworming of nursing bitches/queens;” 4) “does your practice have an established deworming protocol;” 5) “is the protocol given in this survey that of the practice or your personal protocol,” and 6) “how often do you speak to your clients regarding the zoonotic potential of cat/dog worms (helminths).” Information regarding frequency of diagnosis and zoonotic concern of specific parasites was acquired by asking veterinarians, “in your experience, rank the frequency of diagnosis of the following parasites in young and adult cats and dogs (1-never, 5-very common) and your concern regarding each as a potential zoonotic hazard (1-no concern, 3-significant concern).” The following parasites were listed for ranking: T. canis, T. cati, A. caninum, Trichuris vulpis, Toxoplasma gondii, Giardia lamblia, Dipylidium caninum, and Echinococcus spp.

Data analysis

Data on recommended deworming protocol, client education, and demographics were divided into biologically relevant categories that, where possible, would provide relatively equal numbers in each group: recommended age of 1st deworming puppies (≤ 3 wk, > 3 wk, never); kittens (≤ 6 wk, > 6 wk, never); client education regarding zoonotic disease (with all clients, only with those clients at increased risk, only when prompted by the client, when worms are diagnosed, never); and demographics (practitioner type [small, mixed], number of years in practice [< 4, 4–6, 7–9, 10–15, 16–20, > 20], number of veterinarians in the practice [≤ 3, > 3], and number of small animals examined per week [≤ 35, 36–50, 51–75, > 75]). Age at 1st deworming was considered appropriate if complying with established guidelines (puppy ≤ 3 wk, kitten ≤ 6 wk). Pearson’s χ2 test for independence (39) and a χ2 test for trend were used as appropriate to sequentially evaluate the existence of an association between recommended age category at 1st deworming and demographic information, veterinarian-perceived parasite prevalence, and veterinarian-perceived parasite zoonotic concern. A χ2 test for trend was used to determine if perceived zoonotic concern or perceived prevalence of T. canis or T. cati was associated with recommended age of 1st deworming in puppies or kittens, respectively. Logistic regression was performed separately for puppies and kittens, using appropriate age of 1st deworming as a dichotomous outcome and T. canis/cati perceived prevalence, perceived zoonotic concern, and demographic variables determined to be of interest by univariate analysis as covariates. Veterinarian-perceived prevalence and veterinarian-perceived zoonotic risk data were summarized by calculating mean ranks and 95% confidence intervals for each parasite. Comparisons in veterinarian perceptions were made between small and mixed animal practitioners by using the Mann-Whitney test (40). All analyses were performed by using a statistical computer software program (SPSS version 12 for Windows; SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA) with P-values < 0.05 considered statistically significant for all analyses.

Results

Of the 2145 surveys mailed, 638 were returned, of which 545 (25% of all mailed surveys) met the study criteria (small/mixed animal veterinary practitioners in western Canada) and were completed to an extent suitable for analysis. The 4 provinces had different survey return proportions (AB: 26.3% [201/764], BC: 28.7%, [244/849], MB: 20.8% [52/250], SK: 14.5% [41/282]; P < 0.001). Seven respondents did not list the province in which they practiced.

Demographics

Four hundred and thirty-eight different veterinary practices were represented. The number of responding veterinarians varied among provinces, practice type, years in practice, weekly small animal caseload, clinic size, and age at which kittens/puppies were typically first examined (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics of responding veterinarians (western Canada, 2003)

| Result

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Variable | Sample size | (Number [%] unless noted) |

| Province | 545 | |

| Alberta | 201 (36.9) | |

| British Columbia | 244 (44.8) | |

| Manitoba | 52 (9.5) | |

| Saskatchewan | 41 (7.5) | |

| Not stated | 7 (1.3) | |

| Practice type | 545 | |

| Small animal | 379 (69.5) | |

| Mixed animal | 162 (29.7) | |

| Not stated | 4 (0.8) | |

| Years in practice | 534 | 15.3 (9.7)a |

| Small animal caseload/wk | 501 | (35, 50, 75)b |

| Practice size (Number of veterinarians) | 503 | 2.8 (2.0)a |

| Age of puppy/kitten at first exam | 539 | |

| < 6 wk | 11 (2.0) | |

| 6–7 wk | 276 (51.2) | |

| > 7 wk | 252 (46.8) | |

Mean (s)

Quartiles

Deworming protocols and client education

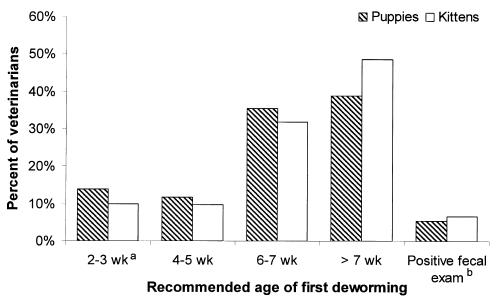

Veterinarian-recommended deworming protocols varied (Table 2). The majority (94.5%) of veterinarians, responding to questions regarding puppy deworming protocols, recommended prophylactically deworming puppies at least once between 1–16 wk of age (Figure 1); mean 6.1 wk [standard deviation (s) = 2.0]. The mean frequency of deworming puppies during the first 16 wk of life was 3.5 treatments (s = 1.7). Sixty-six (13.2%) of the respondents recommended both 1st deworming at ≤ 3 wk and ≥ 3 treatments during the first 16 wk of life.

Table 2.

Veterinarian-recommended deworming protocols for dogs and cats (western Canada, 2003)

| Dog

|

Cat

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age category | Sample size | Number (%) | Sample size | Number (%) |

| Young (1–16 wk of age) | 529 | 543 | ||

| Prophylactically ≥ once | 500 (94.5) | 507 (93.4) | ||

| Following positive fecal examination | 29 (5.5) | 36 (6.6) | ||

| Juvenile (5–12 mo of age) | 494 | 495 | ||

| Prophylactically ≥ once | 254 (51.4) | 248 (50.1) | ||

| Following positive fecal examination | 223 (45.1) | 227 (45.9) | ||

| Not recommended | 17 (3.5) | 20 (4.0) | ||

| Adult (> 12 mo of age) | 523 | 536 | ||

| Prophylactically ≥ once/y | 340 (65.0) | 350 (65.3) | ||

| Following positive fecal examination | 178 (34.0) | 182 (34.0) | ||

| Not recommended | 5 (1.0) | 4 (0.7) | ||

Figure 1.

Veterinarian-recommended age of first kitten/puppy deworming (n = 529; western Canada, 2003).

a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendation

b Recommend deworming only following a positive fecal examination

Similar trends were noted in recommended kitten deworming protocols (Table 2). The majority of respondents (93.4%) recommended prophylactically deworming kittens at least once (Figure 1); mean 6.6 wk (s = 2.0), with a mean frequency of 3.1 (s = 1.6) treatments during the first 16 wk of life. Nearly half of the respondents (48.3%; 245/507) recommended deworming kittens at ≤ 6 wk of age. One hundred and ninety-seven (38.9%) of the respondents recommended both 1st deworming at ≤ 6 wk and ≥ 3 treatments during the first 16 wk of life.

Veterinarians’ recommendations were similar for juvenile (5–12 mo) and adult (> 12 mo) cats and dogs (Table 2). Half of the responding veterinarians recommended prophylactically deworming juveniles during this 8-month period, with a frequency that ranged from 1 to 8 treatments (mean dog 2.2 [s = 1.7]; mean cat 2.0 [s = 1.3]). Results were similar for adult dogs and cats, with most veterinarians (dog: 65.0% [340/523]; cat 65.3% [350/536]) recommending prophylactic deworming with mean yearly frequencies of 2.0 (s = 1.0) and 2.5 (s = 1.3) in dogs and cats, respectively. Seventy-two percent (364/507) of the respondents recommended deworming nursing bitches/ queens. Most responding veterinarians (68.5%; 369/539) stated the clinic at which they worked had an established deworming protocol; however, only 78.3% of these claimed to follow the protocol.

Given identical clinic name, city, and province, 35% of the respondents (192/545) worked at the same clinic as at least 1 other respondent (19% [85/438] of the clinics were represented more than once). Of those respondents working at the same clinic as another respondent, 38% (73/192) stated they followed an established clinic-wide deworming program. Comparison of the protocols from these respondents (age of 1st deworming puppies) revealed only 36% (26/73) were in fact identical.

Forty-four percent (238/539) of respondents reported that they actively discussed with all clients the zoonotic risk of small animal-derived endoparasites. Few (9.8%) reported actively discussing the zoonotic risk with only those at greatest risk (households with children, young animals, and immunocompromised individuals), while 40.3% utilized passive discussions with their clients, including discussing “only when prompted by the client” and “when worms were diagnosed.” Three respondents (0.6%) reported never discussing the zoonotic risk of cat/dog helminths.

Veterinarian-perceived parasite prevalence and zoonotic concern

Median veterinarian-perceived prevalence significantly differed between small and mixed animal practitioners for several parasites (Tables 3 and 4). Within practitioner type (small or mixed), significant differences in perceived parasite prevalence were noted between age groups (young verses adult animals) and between parasites (Tables 3 and 4). Toxocara canis and T. cati were considered of greatest prevalence in young patients, while D. caninum was considered of greatest prevalence in adult patients. Ancylostoma caninum was infrequently diagnosed. Mean/median veterinarian-perceived zoonotic concern significantly differed between several of the parasites and type of practitioner (Table 5). Roundworms (T. canis and T. cati), Giardia, and T. gondii were considered to be of moderate-significant zoonotic concern.

Table 3.

Perceived prevalencea of specific endoparasites in young and adult dogs and cats by small animal veterinarians (western Canada, 2003)

| Young

|

Adult

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parasite | Sample size | Mean Rank | 95% CI | Sample size | Mean Rank | 95% CI |

| Toxocara canis | 353 | 3.6b | 3.5–3.8 | 335 | 2.2b | 2.1–2.3 |

| Toxocara cati | 354 | 3.3b | 3.2–3.4 | 331 | 2.1b | 2.1–2.2 |

| Dipylidium caninum | 340 | 2.4 | 2.3–2.5 | 330 | 2.7 | 2.6–2.9 |

| Giardia lamblia | 351 | 2.4b | 2.3–2.5 | 340 | 2.5b | 2.4–2.6 |

| Other roundworms | 288 | 2.1b | 2.0–2.2 | 260 | 1.6b | 1.5–1.7 |

| Ancylostoma caninum | 333 | 1.8 | 1.7–1.8 | 315 | 1.8 | 1.7–1.9 |

| Trichuris vulpis | 338 | 1.6 | 1.6–1.7 | 318 | 1.6 | 1.5–1.7 |

| Toxoplasma gondii | 342 | 1.4 | 1.4–1.5 | 324 | 1.5 | 1.4–1.5 |

| Echinococcus | 338 | 1.3 | 1.3–1.4 | 319 | 1.3b | 1.3–1.4 |

Table 4.

Perceived prevalencea of specific endoparasites in young and adult dogs and cats by mixed animal veterinarians (western Canada, 2003)

| Young

|

Adult

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parasite | Sample size | Mean Rank | 95% CI | Sample size | Mean Rank | 95% CI |

| Toxocara canis | 144 | 3.8b | 3.6–4.0 | 137 | 2.5b | 2.3–2.7 |

| Toxocara cati | 143 | 3.6b | 3.4–3.8 | 136 | 2.4b | 2.3–2.6 |

| Dipylidium caninum | 136 | 2.4 | 2.2–2.6 | 138 | 2.8 | 2.6–3.1 |

| Giardia lamblia | 140 | 2.2b | 2.0–2.3 | 135 | 2.2b | 2.1–2.4 |

| Other roundworms | 121 | 2.7b | 2.5–2.9 | 120 | 2.1b | 1.9–2.3 |

| Ancylostoma caninum | 131 | 1.9 | 1.7–2.1 | 130 | 1.9 | 1.8–2.1 |

| Trichuris vulpis | 136 | 1.8 | 1.7–2.0 | 131 | 1.7 | 1.6–1.8 |

| Toxoplasma gondii | 136 | 1.5 | 1.4–1.6 | 134 | 1.6 | 1.5–1.7 |

| Echinococcus | 135 | 1.5 | 1.3–1.6 | 133 | 1.8b | 1.6–2.0 |

Table 5.

Veterinarian-perceived zoonotic concern for selected endoparasites of dogs and cats (western Canada, 2003)

| Zoonotic concerna |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parasite | Sample size | Mean Rank | 95% CI |

| Toxocara canis | 492 | 2.3 | 2.2–2.4 |

| Giardia lamblia | 480 | 2.3 | 2.2–2.3 |

| Toxoplasma gondii | 477 | 2.2 | 2.2–2.3 |

| Toxocara cati | 485 | 2.2 | 2.2–2.3 |

| Echinococcus | 443 | 1.9 | 1.8–2.0 |

| Other roundworms | 382 | 1.8 | 1.7–1.9 |

| Ancylostoma caninum | 427 | 1.5 | 1.5–1.6 |

| Dipylidium caninumc | 129 | 1.5 | 1.4–1.6 |

| Dipylidium caninumb | 314 | 1.4 | 1.3–1.4 |

| Trichuris vulpisc | 128 | 1.4 | 1.3–1.5 |

| Trichuris vulpisb | 296 | 1.3 | 1.2–1.3 |

Perceived zoonotic concern: veterinarians ranked each parasite according to their “concern as a potential zoonotic hazard” from 1 (no concern) to 3 (significant concern)

Significant difference (P < 0.05) in median rank between small and mixed animal practitioners (Mann-Whitney test): b = value for small animal practitioners; c = value for mixed animal practitioners

Associations between demographics, veterinarians’ perceptions, and deworming protocols

Univariate analysis revealed number of years in practice, small animal weekly caseload, and use of an established clinic-wide deworming protocol were independent of age of 1st deworming in kittens and puppies (Table 6). Puppy and kitten deworming protocols recommended by recent graduates (< 4 y) did not significantly differ from those of other veterinarians (χ2; P = 0.3 and P = 0.2, respectively). Type of practitioner and practice size were independent of age of 1st deworming in puppies, but they were associated with age of 1st deworming in kittens, with smaller clinics (≤ 3 veterinarians) and mixed animal practitioners associated with higher proportions of deworming ≤ 6 wk of age. Province was associated with age of 1st deworming in puppies, but not kittens.

Table 6.

Proportion of veterinarians whose recommendations followed established deworming guidelinesa, stratified by demographic variables (western Canada, 2003)

| Puppy

|

Kitten

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic variable | n | Deworming ≤ 3 wk (%)a | P-valueb | n | Deworming ≤ 6wk (%)a | P-valueb |

| Province | 0.02 | 0.09 | ||||

| Alberta | 182 | 10.4 | 182 | 42.3 | ||

| British Columbia | 229 | 19.2 | 230 | 54.3 | ||

| Manitoba | 47 | 6.4 | 48 | 43.8 | ||

| Saskatchewan | 39 | 10.3 | 40 | 45.0 | ||

| Practice type | 0.48 | 0.01 | ||||

| Small | 338 | 14.8 | 340 | 44.7 | ||

| Mixed | 161 | 12.4 | 162 | 56.8 | ||

| Years in practice | 0.42c | 0.58c | ||||

| < 4 | 54 | 9.3 | 54 | 40.7 | ||

| 4–6 | 73 | 16.4 | 75 | 52.0 | ||

| 7–9 | 44 | 11.4 | 44 | 50.0 | ||

| 10–15 | 100 | 13.0 | 104 | 46.2 | ||

| 16–20 | 85 | 16.5 | 83 | 49.4 | ||

| > 20 | 138 | 15.2 | 137 | 49.6 | ||

| Small animal caseload/wk | 0.90c | 0.43c | ||||

| ≤ 35 | 127 | 12.6 | 127 | 48.0 | ||

| 36–50 | 126 | 12.7 | 126 | 46.8 | ||

| 51–75 | 112 | 18.8 | 115 | 47.0 | ||

| > 75 | 95 | 10.5 | 94 | 54.3 | ||

| Practice size (# veterinarians) | 0.42 | 0.02 | ||||

| ≤ 3 | 340 | 15.3 | 345 | 52.2 | ||

| > 3 | 122 | 12.3 | 121 | 39.7 | ||

| Use established protocol | 0.33 | 0.41 | ||||

| Yes | 235 | 12.3 | 233 | 46.4 | ||

| No | 267 | 15.4 | 274 | 50.0 | ||

Veterinarian-perceived prevalence and veterianarian-perceived zoonotic risk of several parasites were significantly associated with recommended deworming protocols in dogs and cats (χ2 test for trend; P < 0.05). Increased perceived prevalence of T. canis in young animals was linearly associated with increased proportion of 1st deworming puppies ≤ 3 wk of age. This association did not remain significant in the multivariate model (adjusting for province, practitioner type, practice size, and zoonotic concern — Table 7). A similar trend was noted for perceived zoonotic risk of T. canis with puppy deworming, but remained significant when adjusting for these variables. Trends were also noted in perceived prevalence and zoonotic concern of T. cati in 1st deworming of kittens ≤ 6 wk of age. When adjusting for variables identified during univariate analysis, perceived prevalence of T. cati remained significant, while zoonotic concern was marginally significant (Table 8). The association between practitioner type and appropriate kitten deworming also remained significant in this model.

Table 7.

Multivariable logistic regression modeling appropriate recommended deworming protocols for puppies (outcome)a as a function of veterinarian-perceived Toxocara canis prevalence in young dogs, perceived zoonotic concern, practitioner type, number of veterinarians in the practice, and province; western Canada, 2003 (n = 407)

| Variableb | Odds Ratio (95% CI)c | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Practitioner type | ||

| Small Animal | Referent | |

| Mixed Animal | 0.8 (0.4, 1.7) | 0.64 |

| T. canis (z) | 1.9 (1.2, 3.1) | 0.01 |

| T. canis (p) | 1.3 (0.9, 1.8) | 0.09 |

| Province | 0.07 | |

| Alberta | Referent | |

| British Columbia | 2.1 (1.0, 4.2) | 0.04 |

| Manitoba | 0.5 (0.1, 2.4) | 0.41 |

| Saskatchewan | 0.7 (0.1, 3.3) | 0.65 |

| Practice size | 1.0 (0.9, 1.2) | 0.80 |

An event was characterized as recommending a deworming protocol in which puppies were first dewormed at ≤ 3 wk of age

Perceived prevalence (p) was ranked from 1 (never) to 5 (very common). Perceived zoonotic concern (z) was ranked from 1 (no concern) to 3 (significant concern)

Odds ratio for a one-unit increase in variables (perceived zoonotic concern, perceived prevalence, practice size) or relative to referent for categorical variables (province, practitioner type)

Table 8.

Multivariable logistic regression modeling appropriate recommended deworming protocols for kittens (outcome)a as a function of veterinarian-perceived Toxocara cati prevalence in young cats, perceived zoonotic concern, practitioner type, number of veterinarians in the practice, and province; western Canada, 2003 (n = 399)

| Variableb | Odds Ratio (95% CI)c | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Practitioner type | ||

| Small Animal | Referent | |

| Mixed Animal | 2.1 (1.3, 3.4) | 0.002 |

| T. cati (z) | 1.4 (1.0, 1.9) | 0.06 |

| T. cati (p) | 1.2 (1.0, 1.5) | 0.04 |

| Province | 0.02 | |

| Alberta | Referent | |

| British Columbia | 2.1 (1.3, 3.5) | 0.004 |

| Manitoba | 1.1 (0.5, 2.4) | 0.75 |

| Saskatchewan | 1.0 (0.4, 2.2) | 0.91 |

| Practice size | 0.9 (0.8, 1.0) | 0.11 |

An event was characterized as recommending a deworming protocol in which kittens were first dewormed at ≤ 6 wk of age

Perceived prevalence (p) was ranked from 1 (never) to 5 (very common) in young cats. Perceived zoonotic concern (z) was ranked from 1 (no concern) to 3 (significant concern)

Odds ratio for a one-unit increase in variables (perceived zoonotic concern, perceived prevalence, practice size) or relative to referent for categorical variables (province, practitioner type)

Discussion

As compared with established puppy (2, 4, 6, and 8 wk of age) and kitten (3, 5, 7, 9 wk or 6, 9, 10 wk) deworming protocols (18,19), over 85% of the puppy and 60% to 90% (depending on acceptable age: ≤ 6 wk, ≤ 3 wk, respectively) of the kitten deworming protocols recommended by responding veterinarians were inappropriate. These proportions were similar to those in previous studies (36,37,41). The proportion of veterinarians prophylactically deworming (without a fecal examination) at least once during the first 16 wk of life was greatly increased, 93% to 95%, from previous studies, 33% (35) and 46% (36). Given the high proportion of congenitally infected puppies and false negative fecal examinations, prophylactic deworming is recommended for young animals (18,20,42). Toxocariasis may fail to be diagnosed due to low sensitivity of the fecal test (up to 50% in 1 study [43]), often due to low egg production, which is common in animals less than 4 wk of age (44).

Recommended deworming protocols for juvenile and adult dogs and cats are less well-defined, and include periodic prophylactic or fecal examination-based treatments and monthly prophylaxis (18). Nearly all surveyed veterinarians (97% to 99%) followed these guidelines. The simultaneous deworming of nursing bitches and queens, important in decreasing shedding of roundworms and hookworms, was recommended by a higher percentage of veterinarians (72%) than previously noted (15% to 64% [35,36]). Although the majority of veterinarians acknowledged the existence of an established clinic-wide deworming protocol at their practice, not all followed this protocol. Therefore, the education of veterinarians on appropriate deworming protocols must be performed at the level of the individual veterinarian.

Education is a crucial service veterinarians provide their clients. Although physicians could play a role in educating their clients on the zoonotic potential of helminths, studies indicate that they are even less involved and comfortable with the task than are veterinarians (37,38). Because many of the preventive measures important in the control of zoonotic helminth disease, including proper disposal of feces, washing hands after handling fecal material, and decreasing pica in children, occur outside the veterinary clinic, client education remains vital to the control of these diseases. Many responding veterinarians (46%) did not actively educate clients on the zoonotic risk of small animal-derived endoparasites, despite ranking several common small animal helminths as having a moderate to high perceived prevalence and posing moderate to significant zoonotic risk. These findings are similar to those previously reported (37,38).

Several endoparasites were perceived as moderately to highly prevalent. Results were similar to those of other studies (1,7,8,37), identifying a number of zoonotic helminths potentially occurring in the small animal population in western Canada with substantial frequency. Several endoparasites (roundworms, T. gondii, and Giardia) were identified as perceived by veterinarians to be of moderate-high zoonotic risk, as previously noted (37). The overall perception of zoonotic risk likely incorporated several factors not directly measured by the present study, including likelihood of transmission, prevalence, and severity of illness, and may indicate which parasites are most likely to be discussed in conversation with clients (37).

The present study suggests that changes in puppy deworming protocols are needed throughout western Canada, in all practice types and sizes. It is worrisome that despite previous studies on this topic (35–37,41) and well-established guidelines for appropriate helminth control in small animals (18,19), recent veterinary graduates (< 4 y) did not notably differ from other practitioners regarding deworming recommendations. Appropriate kitten deworming strategies are less clear, as different “adequate” protocols have been proposed. Regardless, most recommended kitten deworming practices in western Canada remain inadequate. This study identified perceived prevalence and perceived zoonotic potential of T. canis and T. cati as positively associated with appropriate recommended deworming practices in puppies and kittens. Because this was a cross-sectional study, it was impossible to determine if increased perception of prevalence, zoonotic risk, or both, resulted in improved deworming recommendations. However, targeted education to the veterinary community concerning true roundworm prevalence and zoonotic hazard may be useful in improving appropriate deworming practices.

The overall response proportion to our questionnaire was 25%. Due to the low response proportion, our results may not be valid. It is expected that veterinarians with an interest, concern, or both, for zoonotic disease deworming protocols may have been more likely to respond to the survey than those who were not interested or concerned. Veterinarians who are interested in deworming protocols may be better educated in this field, biasing the current study toward more appropriate deworming protocols, education practices, and higher perceptions of parasite zoonotic risk/prevalence than actually exist. Therefore, the true level of veterinarian knowledge concerning small animal-derived zoonoses may be worse than this study reports.

Although we attempted to word survey questions clearly, it is possible that respondents may have misunderstood questions. An example of such a misunderstanding may have occurred if veterinarians responded to the question “when do you recommend deworming puppies” with the age that they routinely first examine puppies and are able to discuss deworming protocols. In this instance, the distinction between a veterinarian’s recommendation and daily practice may have been missed. Additional sources of error in this study included unanswered survey questions (left blank) for which direction of the possible error, toward or away from the null, is unclear. There was a concern that numerous responses from the same large clinic might bias the results. However, despite a large percentage of clinics with several respondents, few individuals followed the same protocol as other veterinarians from that clinic, likely having little effect on the results.

Early, prophylactic deworming protocols and client education targeted at the risks and prevention of small animal-derived zoonotic disease are critical components in controlling endoparasite zoonoses. Because most animals are not brought to a veterinarian until ≥ 6 wk of age (as documented in this study), it is important to reach out to clients who have pregnant or newly born animals at home, and provide early prophylactic treatment for endoparasites. Although puppies and kittens may not routinely reach the veterinarian’s care until late in the deworming schedule, veterinarians should recommend appropriate deworming schedules in order to decrease the likelihood of zoonotic disease. Veterinarians should consider measures such as posting deworming recommendations on clinic Web sites and conducting educational outreach to established and prospective breeders to reach animals prior to their 1st routine examination. This study, in accordance with previous studies (35–37,41), documented suboptimal client education and recommended deworming protocols in the veterinary community. Targeted education to the veterinary community concerning roundworm prevalence and zoonotic potential may be useful in improving appropriate deworming practices. Further research into the association of these perceptions and their result on deworming protocols is warranted. CVJ

Footnotes

Dr. Stull’s current address is Public Health Veterinarian, Department of Health and Human Services/Bureau of Disease Control, 29 Hazen Drive, Concord, New Hampshire 03301-6504, USA.

This study was funded in part by Bayer Pharmaceuticals.

References

- 1.Blagburn BL, Lindsay DS, Vaughan JL, et al. Prevalence of canine parasites based on fecal flotation. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet. 1996;18:483–509. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anene BM, Nnaji TO, Chime AB. Intestinal parasitic infections of dogs in the Nsukka area of Enugu State, Nigeria. Prev Vet Med. 1996;27:89–94. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martinez I, Vazquez O, Romero R, Gutierrez EM, Amancio O. The prevalence of Toxocara cati in domestic cats in Mexico City. Vet Parasitol. 2003;114:43–49. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4017(03)00038-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jordan HE, Mullins ST, Stebbins ME. Endoparasitism in dogs: 21,583 cases (1981–1990) J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1993;203:547–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Minnaar WN, Krecek RC, Fourie LJ. Helminths in dogs from a peri-urban resource-limited community in Free State Province, South Africa. Vet Parasitol. 2002;107:343–349. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4017(02)00155-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nolan TJ, Smith G. Time series analysis of endoparasitic infections in cats and dogs presented to a veterinary teaching hospital. Vet Parasitol. 1995;59:87–96. doi: 10.1016/0304-4017(94)00742-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bugg RJ, Robertson ID, Elliot AD, Thompson RCA. Gastrointestinal parasites of urban dogs in Perth, Western Australia. Vet J. 1999;157:295–301. doi: 10.1053/tvjl.1998.0327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pomroy WE. A survey of helminth parasites of cats from Saskatoon. Can Vet J. 1999;40:339–340. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Unruh DHA, King JE, Eaton RDP, Allen JR. Parasites of dogs from Indian settlements in northwestern Canada: A survey with public health implications. Can J Comp Med. 1973;37:25–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malloy WF, Embil JA. Prevalence of Toxocara spp. and other parasites in dogs and cats in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Can J Comp Med. 1978;42:29–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghadirian E, Viens P, Strykowski H, Dubreuil F. Epidemiology of toxocariasis in the Montreal area. Can J Public Health. 1976;67:495–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Desrochers F, Curtis MA. The occurrence of gastrointestinal helminths in dogs from Kuujjuaq (Fort Chimo), Quebec, Canada. Can J Public Health. 1987;78:403–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hackett T, Lappin MR. Prevalence of enteric pathogens in dogs of north-central Colorado. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2003;39:52–56. doi: 10.5326/0390052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hill SL, Cheney JM, Taton-Allen GF, Reif JS, Bruns C, Lappin MR. Prevalence of enteric zoonotic organisms in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2000;216:687–692. doi: 10.2460/javma.2000.216.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sprent JF. Observations on the development of Toxocara canis (Werner, 1782) in the dog. Parasitology. 1958;48:184–209. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000021168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burke MT, Roberson EL. Prenatal and lactational transmission of Toxocara canis and Ancylostoma caninum: Experimental infection of the bitch before pregnancy. Int J Parasitol. 1985;15:71–75. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(85)90104-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Swerczek TW, Nielsen SW, Helmboldt CF. Transmammary passage of Toxocara cati in the cat. Am J Vet Res. 1971;32:89–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [homepage on the Internet] Guidelines for veterinarians: Prevention of zoonotic transmission of ascarids and hookworms of dogs and cats. Available from http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dpd/parasites/ascaris/prevention.htm Last accessed July 16, 2006.

- 19.Schantz PM. Zoonotic ascarids and hookworms: The role for veterinarians in preventing human disease. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet. 2003;24:47–52. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Misra SC. Experimental prenatal infection of Toxocara canis in dogs and effective chemotherapeutic measures. Indian J Anim Sci. 1972;42:608–612. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lloyd S, Amerasinghe PH, Soulsby EJL. Periparturient immunosuppression in the bitch and its influence on infection with Toxocara canis. J Small Anim Pract. 1983;24:237–247. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maizels RM, Meghji M. Repeated patent infection of adult dogs with Toxocara canis. J Helminthol. 1984;58:327–333. doi: 10.1017/s0022149x00025219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Companion Animal Parasite Council (CAPC) [homepage on the Internet]. Available from http://www.capcvet.org Last accessed July 16, 2006.

- 24.Schantz PM, Weis PE, Pollard ZF, White MC. Risk factors for toxocaral ocular larva migrans. A case control study. Am J Public Health. 1980;70:1269–1272. doi: 10.2105/ajph.70.12.1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marmor M, Glickman L, Shofer F, et al. Toxocara canis infection of children: Epidemiologic and neuropsychologic findings. Am J Public Health. 1987;77:554–559. doi: 10.2105/ajph.77.5.554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Malgor R, Oku Y, Gallardo R, Yarzabal I. High prevalence of Ancylostoma spp. infection in dogs, associated with endemic focus of human cutaneous larva migrans, in Tacuarembo, Uruguay. Parasite. 1996;3:131–134. doi: 10.1051/parasite/1996032131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buijs J, Borsboom G, Renting M, et al. Relationship between allergic manifestations and Toxocara seropositivity: A cross-sectional study among elementary school children. Eur Respir J. 1997;10:1467–1475. doi: 10.1183/09031936.97.10071467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khoshoo V, Schantz P, Craver R, Stern GM, Loukas A, Prociv P. Dog hookworm: A cause of eosinophilic enterocolitis in humans. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1994;19:448–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stehr-Green JK, Schantz PM. The impact of zoonotic diseases transmitted by pets on human health and the economy. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 1987;17:1–15. doi: 10.1016/s0195-5616(87)50601-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Embil JA, Tanner CE, Pereira LH, Staudt M, Morrison EG, Gualazzi DA. Seroepidemiologic survey of Toxocara canis infection in urban and rural children. Public Health. 1988;102:129–133. doi: 10.1016/s0033-3506(88)80039-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tanner CE, Staudt M, Adamowski R, Lussier M, Bertrand S, Prichard RK. Seroepidemiological study for five different zoonotic parasites in Northern Quebec. Can J Public Health. 1987;78:262–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Croll NA, Gyorkos TW. Parasitic disease in humans: The extent in Canada. CMAJ. 1979;120:310–312. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wolfe A, Wright IP. Human toxocariasis and direct contact with dogs. Vet Rec. 2003;152:419–422. doi: 10.1136/vr.152.14.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Glickman LT, Schantz PM. Epidemiology and pathogenesis of zoonotic toxocariasis. Epidemiol Rev. 1981;3:230–250. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kornblatt AN, Schantz PM. Veterinary and public health considerations in canine roundworm control: A survey of practising veterinarians. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1980;177:1212–1215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harvey JB, Roberts JM, Schantz PM. Survey of veterinarians’ recommendations for treatment and control of intestinal parasites in dogs: public health implications. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1991;199:702–707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gauthier JL, Richardson DJ. Knowledge and attitudes about zoonotic helminths: A survey of Connecticut pediatricians and veterinarians. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet. 2002;24:4–9. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grant S, Olsen CW. Preventing zoonotic diseases in immunocompromised persons: The role of physicians and veterinarians. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5:159–163. doi: 10.3201/eid0501.990121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pearson K. On the criterion that a given system of deviations from the probable in the case of correlated system of variables is such that it can be reasonably supposed to have arisen from random sampling. Philosophical Magazine. 1900;50:157–172. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mann HB, Whitney DR. On a test of whether one of two random variables is stochastically larger than the other. Ann Math Stat. 1947;18:50–60. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Overgaauw PAM. Effect of a government educational campaign in the Netherlands on awareness of Toxocara and toxocarosis. Prev Vet Med. 1996;28:165–174. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stehr-Green JK, Murray G, Schantz PM, Wahlquist SP. Intestinal parasites in pet store puppies in Atlanta. Am J Public Health. 1987;77:345–346. doi: 10.2105/ajph.77.3.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lillis W. Helminth survey of dogs and cats in New Jersey. J Parasitol. 1967;53:1082–1084. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Parsons JC. Ascarid infections of cats and dogs. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 1987;17:1307–1339. doi: 10.1016/s0195-5616(87)50004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]