Abstract

In science, theories lend coherence to vast amounts of descriptive information. However, current diagnostic approaches in psychopathology are primarily atheoretical, emphasizing description over etiological mechanisms. We describe the importance of Polyvagal Theory toward understanding the etiology of emotion dysregulation, a hallmark of psychopathology. When combined with theories of social reinforcement and motivation, Polyvagal Theory specifies etiological mechanisms through which distinct patterns of psychopathology emerge. In this paper, we summarize three studies evaluating autonomic nervous system functioning in children with conduct problems, ages 4-18. At all age ranges, these children exhibit attenuated sympathetic nervous system responses to reward, suggesting deficiencies in approach motivation. By middle school, this reward insensitivity is met with inadequate vagal modulation of cardiac output, suggesting additional deficiencies in emotion regulation. We propose a biosocial developmental model of conduct problems in which inherited impulsivity is amplified through social reinforcement of emotional lability. Implications for early intervention are discussed.

Keywords: Cardiac vagal control, Cardiac vagal tone, Respiratory sinus arrhythmia, Conduct disorder, Developmental psychopathology, Autonomic nervous system

Scientific observation can generate an overwhelming excess of descriptive information. This is exemplified in the work of Charles Darwin, who in five years aboard the H.M.S. Beagle compiled 20 field notebooks, 8 volumes of diaries, and a 6-part catalogue of species. These works were unparalleled in both scope and detail, and uncovered several anomalies that could not be explained by prevailing theories of the day. The most famous of these is Darwin’s observation of structural variation in the beaks of 13 finch species, and his subsequent recognition that each species was confined to a particular environmental niche of the Galápagos Islands.

The significance of Darwin’s descriptive work can hardly be overstated. Yet description alone does not constitute science. Rather, science ultimately seeks satisfactory explanations for observed events or phenomena (Popper, 1985). Such explanations constitute theories regarding the mechanisms through which observed events or conditions occur. In Darwin’s case, the theory of evolution based on natural selection is by far his greatest contribution to science, and remains among the most important explanatory insights ever advanced. Evolutionary theory lends coherence to a perplexingly vast degree of speciation that before had been inexplicable.

Despite the importance of theories as organizing constructs in science, it is not uncommon for scientific disciplines to become mired in controversies over descriptive convention. In a public lecture in May of 2002, the late Stephen Jay Gould noted that a preoccupation with the descriptive features of dinosaurs has diverted paleontologists from pursuing evolutionary mechanisms of phenotypic variation, even though questions concerning such mechanisms are of far greater significance. In psychiatry, the proliferation of syndromes in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, from 106 in 1952 (DSM-I)to 365 in 1994 (DSM-IV), suggests an analogous preoccupation with description over etiological mechanisms (Beauchaine, 2003; Beauchaine & Marsh, in press; Houts, 2002). In fact, an explicit objective of the American Psychiatric Association in constructing the DSM-IV (2000) was to compile criterion lists that were purposefully descriptive and atheoretical. This strategy was intended to move psychiatry away from psychoanalytically derived syndromes that were low in reliability, to empirically based syndromes that were replicable across raters and sites. Although successful in improving diagnostic reliability, the strictly descriptive approach places inordinate emphasis on the topography of behavior. In many cases, this results in arbitrary distinctions among seemingly different disorders that are in reality alternative manifestations of common genetic vulnerabilities (see Beauchaine & Marsh, in press, Krueger et al., 2002). Thus, without theories regarding the etiological mechanisms of psychopathology guiding classification, we are likely to fail in our efforts to ‘carve nature at its joints’. The result is a complex list of diagnostic classes with perplexing patterns of overlap, or comorbidity (see, e.g., Klein & Riso, 1993). Resolving these perplexities will not be accomplished by engaging in ever more description. What is needed are organizing theories that specify etiological mechanisms, both common and unique, through which patterns of psychopathology emerge.

With this discussion in mind, our main objective in writing this paper is to describe the organizing role of Polyvagal Theory (Porges, 1995, 1997, 1998, 2001, 2003) for our program of research on externalizing psychopathology in children and adolescents. Before proceeding, however, it is important to juxtapose the role of theory in the behavioral sciences with the role of theory in other scientific disciplines. In physics, for example, scientists have long sought a single Grand Unified Theory to account for the strong (atomic), weak (radioactive), and electromagnetic forces in nature. The emergence of such a theory is considered by many to be a prerequisite for a comprehensive understanding of the observed universe. In contrast, grand theories will probably never emerge for phenomena studied in most other scientific disciplines. This is because causal mechanisms operate at many levels of analysis, each of which requires its own theory to explain. Consider evolution by natural selection. Selection occurs at the phenotypic level, where individual differences affect the probability of survival for organisms in their environment of adaptation. At this level of analysis, the mechanism of selection is survival based on heritable variation in phenotypic traits, the foundation of evolutionary theory. Note, however, that this tells us nothing about mechanisms of heritability, which were described by Gregor Mendel and later applied to evolution well after Darwin proposed his theory of natural selection. Thus, a full understanding of evolution requires separate but interactive theories of natural selection, heritability, and other implicated processes such as molecular genetics, each of which operates at a different level of analysis.

The same is true for psychopathology, which is manifested in complex interactions between individuals and their environments over time. These behavioral patterns are both affected by and effected across multiple levels of analysis, including genotypic, endophenotypic, phenotypic, behavioral, and social. Given this, no single theory can be expected to account for any particular psychiatric disorder, much less psychopathology in general. Nevertheless, Polyvagal Theory has emerged as an important explanatory construct for a wide range of psychiatric conditions (Beauchaine, 2001). As we will demonstrate below, when used in conjunction with theories of social reinforcement and motivation, Polyvagal Theory furthers our understanding of the autonomic and central nervous system substrates of emotion regulation and emotional lability, and suggests possible intervention points for serious externalizing behavior.

Polyvagal Theory

We assume that most readers are familiar with Polyvagal Theory, and we therefore provide only a brief overview, focusing on aspects that are most central to our work. Readers who are unfamiliar with the theory are referred to Porges (1995, 1997, 1998, 2001, 2003, this volume) for more comprehensive accounts.

Polyvagal Theory specifies two distinct branches of the vagus, or tenth cranial nerve. These include a phylogenetically older branch originating in the dorsal motor nucleus (DMX), and a newer branch originating in the nucleus ambiguus (NA). The DMX and NA are located in the dorsal and ventral vagal complexes, respectively, adjacent neural structures in the medulla. Although both branches provide inhibitory input to the heart via the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS)1, they do so in the service of distinct evolutionary functions. The DMX branch, sometimes referred to as the vegetative vagus, is rooted in the primary survival strategy of primitive vertebrates, amphibians, and reptiles, which freeze when threatened. Accordingly, the vegetative vagus functions to suppress metabolic demands under condition of danger. In contrast, the NA branch, or smart vagus, is distinctly mammalian, and evolved in conjunction with the need to dynamically regulate substantially increased metabolic output. This includes modulation of fight/flight (F/F) responding in the service of social affiliative behaviors. After orienting to a conspecific, mammals must either engage in social affiliation, or initiate F/F responding. The former requires sustained attention, which is accompanied by vagally mediated heart rate deceleration (Suess, Porges, & Plude, 1994; Weber, van der Molen, & Molenaar, 1994). In contrast, fighting and fleeing are characterized by rage and panic, respectively, which are associated with near complete vagal withdrawal (George et al., 1989; Friedman & Thayer, 1998a, 1998b; see also Porges, 1995, 2001). This facilitates large increases in cardiac output by the sympathetic nervous system (SNS), which is no longer opposed by inhibitory vagal influences. Thus, the smart vagus inhibits acceleratory SNS input to the heart when sustained attention and/or social engagement are adaptive, and withdraws this inhibitory influence when fighting or fleeing are adaptive.

Although the above description has clear implications for psychopathology, two additional attributes of Polyvagal Theory must be considered before proceeding. First, functional organization of the mammalian autonomic nervous system (ANS) is assumed to be phylogenetically hierarchical, with response strategies to threat dictated by the newest neural structures initially, followed by the next newest structures when a given response strategy fails. Thus, if vagally mediated social affiliative behaviors are ineffective in coping with a stimulus, response strategies shift to F/F behaviors, mediated by the phylogenetically older SNS. If F/F responding also fails, immobilization behaviors are initiated, which are mediated by the vegetative vagus, the oldest available response system (Porges, 2001). Second, emotion regulation and social affiliation are considered emergent properties of the regulatory functions served by the smart vagus. Deployment of the newer vagal system suppresses the robust emotional reactions that characterize F/F responding, a prerequisite for the emergence of complex social behavior.

Hierarchical organization of the ANS, coupled with the modulating effects of the smart vagus on SNS-mediated F/F responding, suggests that functional deficiencies of the smart vagus should place individuals at risk for emotional lability, a hallmark of psychopathology (Beauchaine, 2001). Moreover, because F/F response tendencies evoke strong approach (anger) and avoidance (depression, anxiety) emotions, reduced cardiac vagal tone should be observed across a wide range of psychiatric conditions in which dysregulated emotion occurs. Consistent with this prediction, attenuated vagal tone has been observed among antisocial and parasuicidal children and adolescents (Beauchaine, Katkin, Strassberg, & Snarr, 2001; Crowell, Beauchaine, McCauley, & Smith, in press; Mezzacappa et al., 1997), trait hostile adults (Sloan et al., 1994), and depressed, anxious, and panic disordered groups (Lyonfields, Borkovec, & Thayer, 1995; Rechlin, Weis, Spitzer, & Kaschka, 1994; Thayer, Friedman, & Borkovec 1996; Yeragani et al., 1991, 1993; see also Rottenberg, Wilhelm, Gross, & Gotlib, 2003). Furthermore, excessive vagal reactivity to various challenges has been observed among children who are both temperamentally shy and angrily reactive (Donzella, Gunnar, Krueger, & Alwin, 2000; Schmidt, Fox, Schulkin, & Gold, 1999), and among patients with panic disorder (Yeragani et al., 1991). In contrast, vagal tone is positively associated with children’s social engagement (Fox & Field, 1989), with teacher reports of social competence (Eisenberg et al., 1995), and with expressions of empathy toward others in distress (Fabes, Eisenberg, & Eisenbud, 1993). These findings are consistent with the hypothesis that the ventral vagal complex evolved to facilitate social communication and emotion regulation. High vagal tone also appears to buffer children who witness marital conflict and hostility from associated risk of developing both internalizing and externalizing behavior patterns (El-Sheikh, Harger, & Whitson, 2001; Katz & Gottman, 1995, 1997).

The Role of Motivation

As the above discussion suggests, it is now well established that deficient vagal tone and excessive vagal reactivity mark a broad range of psychiatric disorders, and that the common feature among these conditions is dysregulated emotion. It is also well established that cardiac vagal tone marks individual differences in emotion regulation capabilities (for a review see Beauchaine, 2001). Polyvagal Theory provides a context for understanding emotion dysregulation as a failure of the phylogenetically newer vagal system, which results in deployment of SNS-mediated F/F response strategies in situations where they are not adaptive. Yet if we accept the premise that disruptions in vagal functioning potentiate F/F responding, and that this contributes to the development and maintenance of psychopathology, we are still left with the question of why some emotionally labile individuals respond more often with appetitive (including fight) behaviors, as in the case of externalizing disorders, while others respond more often with aversive (including flight) behaviors, as in the case of internalizing disorders. Consistent with Polyvagal Theory, we have argued that both fight and flight behaviors are mediated peripherally by the SNS, and that theories of appetitive and aversive motivation must be considered in order to account for the predominant response set (approach vs. avoidance) observed in different forms of psychopathology (Beauchaine, 2001, 2002; Beauchaine et al., 2001). Specifically, we have argued that an under-responsive central reward system, resulting in a chronically irritable mood state, coupled with deficient vagal modulation of emotion, leads to the sensation-seeking and aggressive behaviors characteristic of conduct disorder and delinquency. In contrast, an over-responsive central inhibition system, resulting in high trait anxiety, coupled with deficient vagal modulation of emotion, leads to the withdrawal behaviors characteristic of anxiety and panic disorders (Beauchaine, 2001, Beauchaine et al., 2001, Brenner, Beauchaine, & Sylvers, 2005).

This formulation relies heavily on Gray’s theory of motivation (Gray, 1970, 1987; Gray & McNaughton, 2000; McNaughton & Corr, 2004). Based on extensive animal and pharmacological work, Gray proposed a behavioral approach system (BAS) and a behavioral inhibition system (BIS). The BAS governs appetitive behaviors in response to reward, and is mediated by dopaminergic pathways including the ventral tegmental area and the nucleus accumbens of the ventral striatum. These neural structures are infused with dopamine following appetitive behaviors, resulting in post-consumatory pleasurable affective states (Nader, Bechara, & van der Kooy, 1997). Recent neuroimaging studies have revealed under-activity in the striatum and its frontal projections among externalizing children and adolescents, which appears to be partially normalized by methylphenidate administration (Bush et al., 1999; Vaidya et al., 1998). In turn, low central dopamine activity has been associated with trait irritability (Laakso et al., 2003), which may lead affected individuals to seek larger and larger rewards to achieve reinforcing levels of post-consumatory contentment. It is worth reemphasizing that consistent with Polyvagal Theory, we have asserted that BAS dysregulation is particularly problematic when coupled with insufficient vagal modulation of negative emotion, and that efficient emotion regulation serves to buffer children who are at risk for sensation seeking and aggression due to chronically low central dopamine activity.

In contrast to the BAS, the BIS inhibits prepotent behaviors when conflict arises due to competing motivational objectives. These competing objectives may represent approach-approach conflicts, avoidance-avoidance conflicts, or approach-avoidance conflicts. BIS activation induces anxiety, which facilitates behaviors aimed at resolving the divergent motivational goals (McNaughton & Corr, 2004). The BIS is mediated by a network of neural structures including the amygdala and the septo-hippocampal system. Although the BIS will not be discussed further in this paper due to space constraints, excessive BIS activity has been linked to heightened risk for internalizing disorders, whereas deficient BIS activity has been linked to behavioral disinhibition (Beauchaine, 2001).

In the sections to follow, we discuss three studies of externalizing behavior spanning preschool to adolescence, and describe how Polyvagal, motivational, and social reinforcement theories lend coherence to our findings. First, however, we provide a brief summary of the premises outlined in this paper thus far:

The smart vagus, originating in NA, evolved to dynamically regulate the considerable metabolic output of mammals.

Inhibition of F/F responding, a necessary component of effective metabolic regulation, facilitated the evolution of social affiliative behaviors.

When confronted with threat, mammals deploy vagally-mediated social affiliative strategies first, followed by SNS-mediated behaviors if their initial coping strategies fail.

When the phylogenetically newer vagal system is compromised, as in the case of many psychiatric disorders, emotional lability ensues, and an individual’s dominant response strategy shifts to F/F behaviors.

The predominant valence (approach vs. avoidance) of F/F responding is dictated by individual differences in BAS and BIS functioning. Predominance of the BAS, reflected in chronically deficient central dopamine activity, confers risk for sensation seeking and aggression, whereas predominance of the BIS confers risk for anxiety disorders and panic.

Strong emotion regulation serves to buffer children who are at risk for psychopathology due to functional deficiencies in either the BAS or the BIS.

In the past five years, we have completed a series of studies aimed at evaluating the combined polyvagal and motivational models for characterizing externalizing behavior patterns among children and adolescents. These studies have focused on three primary research questions: First, are vagal deficiencies observed in aggressive children and adolescents, as predicted by Polyvagal Theory? Second, if vagal deficiencies are observed among aggressive children and adolescents, when in development do group differences emerge? This question is important because several authors have suggested that emotion regulation is largely socialized (e.g., Calkins, 1997; Stifter & Fox, 1990; Shipman & Zeman, 2001). If this hypothesis is correct, identifying the point at which endophenotypic markers of emotion dysregulation emerge could have important implications for prevention and intervention (Beauchaine, 2003). Finally, are vagal deficiencies among aggressive children accompanied by concurrent BAS deficiencies, as predicted by motivational theory?

In each of the studies to be described, we have used respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA) and cardiac pre-ejection period (PEP) to index vagal activity and BAS activity, respectively, both at baseline and during conditions designed to elicit emotional reactivity and reward sensitivity. Consistent with established guidelines, RSA has been defined as the component of heart rate variability exceeding .15 Hz (see Berntson et al., 1997), whereas PEP has been defined as the time between the onset of left ventricular depolarization, measured as the onset of the Q wave from a standard electrogardiogram, and the ejection of blood into the aorta, measure as the onset of the B wave from an impedance cardiogram (Sherwood et al., 1990). RSA and PEP have been validated as indices of PNS and SNS influence on cardiac functioning, respectively, through pharmacologic blockade (Hayano et al., 1991; Sherwood, Allen, Obrist, & Langer, 1986). The assertion that PEP marks BAS activity during appetitive motivational states is based on both functional and phylogenetic considerations. Behavioral approach requires expenditures of energy, and the functional role of the SNS has traditionally been viewed as one of mobilizing resources to meet environmental demands. Moreover, increases in cardiac output required for behavioral approach are mediated in part by sympathetically induced changes in the contractile force of the left ventricle (Sherwood et al., 1986, 1990). Furthermore, infusions of DA agonists into the ventral tegmental area, the neural substrate of the BAS, result in sympathetically-mediated increases in blood pressure and cardiac output (van den Buuse, 1998). Finally, our previous work with children, adolescents, and adults has demonstrated shortened PEP in normal participants specifically during reward (Beauchaine et al., 2001; Beauchaine, 2003; Crowell, Beauchaine, Gatzke-Kopp, Sylvers, & Mead, 2004), but not during extinction or mood induction (Brenner et al., 2005).

Study 1: Adolescence

In our first study (Beauchaine, 2002; Beauchaine et al., 2001), we monitored both RSA and PEP while 17 adolescents with ADHD, 20 adolescents with aggressive conduct disorder (CD), and 22 control adolescents played a monetary incentive task, and while they watched a videotaped conflict between age- and race-matched peers. Participants were all males between the ages of 12 and 17, and were selected based on both Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach, 1991) and Adolescent Symptom Inventory (ASI; Gadow & Sprafkin, 1998) cutoffs. Those in the CD group were required to meet DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for conduct disorder on the ASI, and to obtain T-scores placing them at or above the 95th percentile on both the Delinquent Behavior and Aggressive Behavior subscales of the CBCL. Those in the ADHD group were required to meet DSM-IV criteria for the hyperactive/impulsive subtype of ADHD, to score at or above the 95th percentile on the CBCL Attention Problems scale, to score below the 70th percentile on the CBCL Delinquency scale, and to endorse no CD criteria. Control group participants were included if they failed to meet DSM-IV criteria for any disorder and their T-scores on all CBCL scales were below the 60th percentile.

During the task, initially described by Iaboni, Douglas, and Ditto (1997), large, single-digit odd numbers (i.e., 1, 3, 5, 7, or 9) were presented in random order on a monitor situated just above eye level. Participants were required to press the matching number on a 10-key pad mounted on a platform in front of them, and then press the enter key to initiate the next stimulus. The task therefore required only small movements of participants’ dominant hand. After 2 min of practice, the task was performed across six 2 min blocks, each separated by a 2.5 min rest period. The first three blocks were Reward trials in which signal tones and 3¢ incentives accompanied correct responses. Signal tones and incentives were omitted for incorrect responses, and numbers remained on the screen until the participant entered a correct response. The fourth block included 30 s of Reward and 90 s of Extinction during which incentives and signal tones were omitted. The fifth block was purely Reward, with signal tones and incentives reinstated. The sixth block included 90 s of Extinction followed by 30 s of Reward. Throughout all trials the amount of money earned was displayed in the upper right corner of the projection screen. Participants were told that they could earn more money the faster they played, that most people earn about $25, and that they needed to continue responding during periods of Extinction in order to advance to the next Reward block. For the present paper, only cardiac responses to reward are discussed.

After a 2.5 min rest period following the incentive task, participants were shown a 2 min video of two peers engaged in an argument that began with a minor disagreement and ended with one peer pushing the other. The argument progressed through four 30 s phases, including (a) two male adolescents sitting in a waiting room reading magazines; (b) one asking the other to relinquish his magazine, a request that was met with verbal resistance; (c) the antagonist repeatedly demanding the magazine in a threatening tone; and (d) the two standing face-to-face yelling at one another, with one pushing the other at the end.

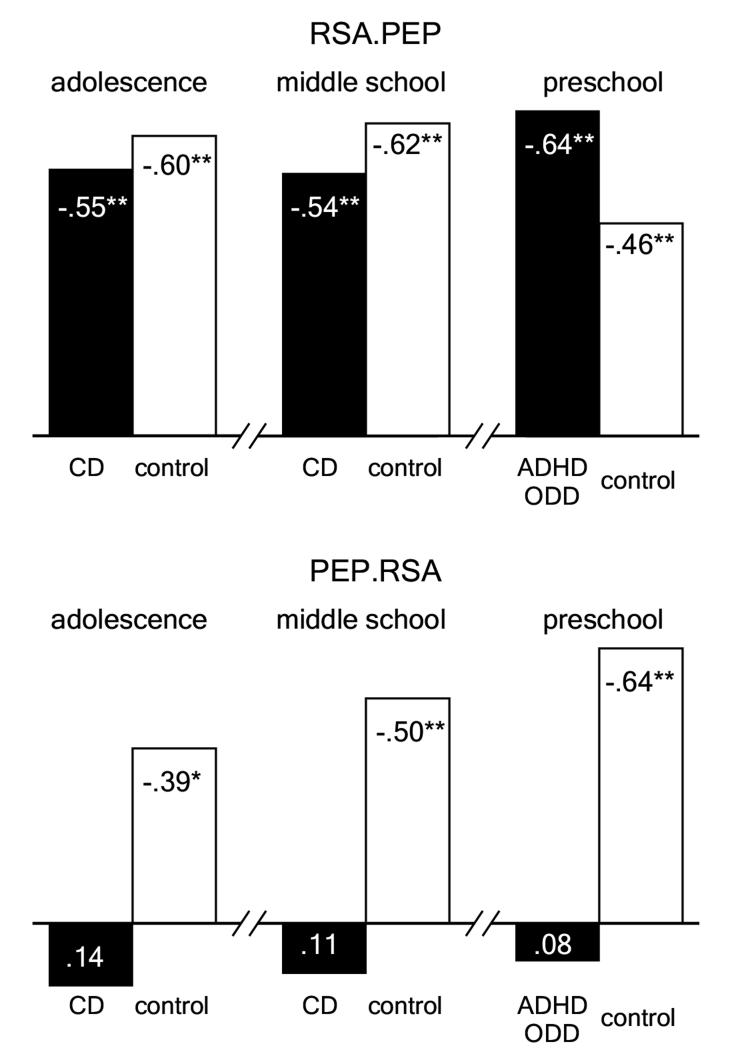

Several interesting findings emerged from this study. As expected, baseline RSA was significantly attenuated in the aggressive CD group compared with controls. Second, all groups exhibited decreasing RSA across the escalating videotaped conflict. Thus, as the vignettes became progressively more threatening, RSA declined, consistent with the hypothesized evolutionary function of vagal withdrawal in preparedness for F/F responding. Assuming that degree of vagal influence, and not degree of vagal withdrawal, is critical in reaching the threshold of F/F responding, the significantly lower vagal tone at baseline observed in the CD group may place CD participants closer to the threshold for F/F behaviors even in the presence of RSA reductions equivalent to those of the control group. Thus, normative reductions in RSA during threat may be more critical for CD participants as they act on an already compromised system. The CD group also exhibited lengthened PEPs at baseline and less PEP reactivity (shortening) during the monetary incentive task, indicating SNS-insensitivity to reward. Moreover, as depicted in Figure 1, partial correlation coefficients indicated that heart rate (HR) changes among CD participants were mediated exclusively by PNS withdrawal, with no independent SNS contribution. In contrast, HR changes among ADHD participants and controls were mediated by both autonomic branches.

Figure 1.

Partial correlations between changes in heart rate and changes in RSA and PEP during reward tasks. The top panels indicate the independent effects of RSA reactivity on heart rate, controlling for PEP reactivity. The bottom panels indicate the independent effects of PEP reactivity on heart rate, controlling for RSA reactivity. Negative correlations are indicated by bars rising above the x-axis because they represent positive chronotropic effects for both RSA and PEP. RSA = respiratory sinus arrhythmia; PEP = preejection period; CD = conduct disorder; ADHD = attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ODD = oppositional defiant disorder. *p<.05, **p ≤ .01.

Study 2: Middle Childhood

In our next study (Mead et al., 2004), we extended this paradigm to younger male children with aggressive ODD and/or CD (n = 23) and those with no psychiatric disorder (n = 17), ages 8-12. Selection criteria for both groups were similar to those used in Study 1. Participants engaged in the same monetary incentive task as that described above, which was followed by presentation of a 3 min film clip of “The Champ”, which depicts a young boy with his dying father. This clip has been used by a number of researchers to evoke feelings of sadness and empathy (e.g., Gross & Levenson, 1995). Our objective in including it was to assess potential differences in RSA reactivity between participants with ODD/CD and controls given the empirical relations linking vagal tone to empathy, as described in previous research (Fabes, Eisenberg, & Eisenbud, 1993).

Results from this study were remarkably consistent with those reported above for the adolescent sample. Baseline RSA was significantly attenuated in the aggressive ODD/CD group compared with controls. Moreover, both ODD/CD participants and controls exhibited decreasing RSA across the three minute film clip. Thus, as the young boy in the film clip became increasingly inconsolable while his father died, RSA reductions were observed in both groups. Once again, however, equivalent reductions in RSA may be more costly for ODD/CD participants given their baseline deficiencies. Although differences in PEP were not observed at baseline, the ODD/CD group again exhibited less PEP reactivity to the monetary incentive task, indicating SNS-insensitivity to reward. Also consistent with results from adolescents (see Figure 1), partial correlation coefficients indicated that HR changes during reward among ODD/CD participants were mediated exclusively by PNS withdrawal, with no independent SNS contribution. In comparison, HR changes among controls were mediated by both autonomic branches.

Study 3: Preschool

In a third study that we recently completed (Crowell et al., 2004), we used a modified reward task to examine RSA and PEP reactivity among preschoolers, ages 4-6. Participants included 20 control children (9 girls, 11 boys) and 18 children with both ADHD and oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) (7 girls, 11 boys). An ADHD/ODD group was recruited because few children in this age range meet criteria for CD, yet children with both ADHD and ODD are at considerable risk for developing more serious conduct problems in later childhood (Campbell, Shaw, & Gilliom, 2000). Thus, our objective was to determine whether attenuated RSA and/or attenuated PEP are present in at risk children before CD develops. Diagnostic status was ascertained using the CBCL (Achenbach, 1991) and the Child Symptom Inventory (Gadow & Sprafkin, 1997), with the same cutoffs for relevant disorders described under Study 1.

Patterns of cardiac activity were monitored during a 5 min baseline, after which children played Perfection®, a commercially available game designed for 4-7-year-olds that was used to elicit responses to reward. Children were required to place a number of shapes (e.g., half moons, rectangles) into corresponding holes before a spring-loaded platform ejected the pieces after 1 min. To increase the reward value of the game, children were shown a large container of toys valued at $10 each, and told that they could pick any toy they wanted if they completed the game on time. A modified reward task was required because the game used with older children and adolescents is too difficult for some preschool children. After the game, all children were given their chosen toy for “trying hard”.

Consistent with findings from our previous studies with older children and adolescents, attenuated PEPs were observed among ADHD/ODD preschoolers, both at baseline and during reward. Furthermore, as depicted in Figure 1, HR changes among ADHD/ODD children were mediated exclusively by the PNS, as was the case among both groups of older children with ODD/CD. In contrast to the older ODD/CD groups, however, no differences were observed between the ADHD/ODD participants and controls for RSA. One possible source of the discrepancy between preschoolers and older children is the differential sex distribution across studies, with girls being included only in the preschool sample. Because girls have exhibited higher baseline RSA in some studies (e.g., Fabes, Eisenberg, Karbon, Troyer, & Switzer, 1994), it was important to rule out the possibility that a sex effect or a group × sex interaction had washed out any group main effect. However, neither the sex effect nor the group × sex interaction were significant. Perhaps more importantly given the small sample, the effect size separating male and female participants on RSA was exceedingly small (d = .01). Thus, failure to find a group difference was probably not the result of a confounding sex effect.

Implications and Links to Polyvagal Theory

As outlined above, these studies were conducted in order to address three primary questions. The first was to determine whether vagal deficiencies are observed in aggressive children and adolescents, as predicted by Polyvagal Theory. Consistent with previous research (Mezzacappa et al., 1997; Pine et al., 1998), both middle school and adolescent males with aggressive ODD/CD exhibited attenuated RSA at baseline, and while watching both sad and threatening film clips. These findings add to a large and growing literature linking reduced parasympathetic cardiac control to aggression, and to dysregulated emotion more generally (e.g., Beauchaine, 2001; Gottman & Katz, 2002).

Second, we sought to determine when in development group differences in RSA emerge. Notably, preschool children at risk for conduct problems by virtue of concurrent diagnoses of ADHD and ODD did not exhibit reduced vagal tone or excessive vagal reactivity. Thus, reductions in vagal tone observed among older children with aggressive ODD/CD appear to develop sometime between the preschool and the middle school years. Given findings suggesting that (a) emotion regulation and vagal tone are largely socialized within families (Calkins, 1997; Stifter & Fox, 1990; Shipman & Zeman, 2001), and (b) emotion regulation and vagal tone buffer children from developing internalizing and externalizing behaviors in adverse environments (Gottman & Katz, 2002; Katz & Gottman, 1997, 1998), elucidating the processes through which emotional lability and attenuated RSA emerge in young children with conduct problems should become a high priority. We return to this issue below, where we present a biosocial developmental model of emotion dysregulation in aggressive children.

Finally, we wanted to determine whether vagal deficiencies among aggressive children were accompanied by concurrent BAS deficiencies, as predicted by motivational theory. At all ages considered, children with aggressive ODD/CD, and children at risk for developing aggressive CD, exhibited attenuated SNS-linked cardiac activity at baseline, and showed PEP non-reactivity to incentives. Moreover, HR changes observed while participants responded for reward were mediated exclusively by PNS withdrawal, with no independent SNS contribution. We have argued elsewhere that SNS-linked cardiac insensitivity to reward serves as a peripheral index of low central dopamine activity in the striatum and its prefrontal projections, the neurological substrate of the BAS, and of many impulsive and sensation seeking behaviors (Beauchaine, 2002; Beauchaine et al., 2001; Brenner et al., 2005). Our findings suggest that these motivational deficiencies are in place before reductions in vagal tone emerge.

Placed in the context of Polyvagal Theory, children with aggressive ODD/CD appear to be in double jeopardy. First, they exhibit both sympathetic underarousal at baseline and sympathetic insensitivity to reward at a very early age, marking a general disinhibitory tendency.. Second, this disinhibition is met with PNS deficiencies that contribute to increased emotional lability (see also Boyce et al., 2001). In all likelihood, this places them at risk for a host of psychopathological conditions covering the entire externalizing spectrum. Chronically reduced central dopamine activity, theorized to be reflected in lengthened PEP values at rest, has been linked to numerous disinhibitory conditions, including ADHD, conduct problems, alcohol abuse, and substance dependencies (e.g., Bush et al., 1999; De Witte, Pinto, Ansseau, & Verbanck, 2003; Durston et al., 2003; Laine, Ahonen, Rasanen, & Tiihonen, 2001; Vaidya, et al., 1998). According to Polyvagal Theory, SNS-mediated response strategies predominate when emotion regulatory functions served by the PNS via the smart vagus fail. Sometime after the preschool years, a period long recognized as important for the acquisition of effective emotion regulation and executive control (see Blair, 2002), vagal deficiencies and associated emotional lability emerge among aggressive ODD/CD children. This is likely to represent a failure in development for affected individuals, who do not acquire the self regulatory, executive functioning, and attentional capabilities that are developing normally in their peers. Polyvagal Theory suggests that difficulties in these areas, each of which is marked by attenuated vagal tone (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 1995; Hansen, Johnsen, & Thayer, 2003; Suess et al., 1994), follow failure of the smart vagus to inhibit prepotent behaviors when attentional allocation is adaptive. Ineffective vagal modulation of emotion, mediated by the PNS, and compromised reward sensitivity, mediated by the SNS, leave aggressive CD children with no viable response mechanism to inhibit labile and impulsive behaviors.

A Biosocial Developmental Model

Several authors have noted that the preschool years represent a critical period during which developing noradrenergic, serotonergic, and dopaminergic systems that govern behavioral control are vulnerable to potential long-term changes in functioning (e.g., Bremner, & Vermetten, 2001; Pine et al., 1996; Schwarz, & Perry, 1994). These systems may therefore be malleable in very young children, and altered in response to environmental influences, conferring additional risk for psychopathology in cases of environmental stress and challenge, or protection against the development of psychopathology in cases of environmental enrichment. For example, attenuated electrodermal responding, which marks both serotonergic and noradrenergic dysregulation (see Beauchaine, 2001), is a robust autonomic marker of impulsivity in children and adolescents (e.g., Beauchaine et al., 2001; Delameter & Lahey, 1983). Raine et al. (2001)reported that an enriched preschool environment, including child social skills training, extensive parental involvement, thorough instruction of teachers in behavioral management, and weekly counseling sessions for parents, conferred a 61% increase in electrodermal activity on children 6-8 years later, compared with controls who were assigned randomly to a no treatment condition. Thus, although impulsivity is highly heritable (Swanson & Castellanos, 2002), these data suggest that long-term changes in biological systems implicated in impulsive behavior can be effected through multifaceted environmental interventions in the preschool years. Early intervention may therefore be essential if dysregulated trajectories in responding within these systems are to be prevented and/or altered.

The biobehavioral systems underlying emotion regulation may be even more responsive to environmental input in very young children. As noted above, several authors have suggested that emotion regulation skills are largely socialized within families (e.g., Calkins, 1997; Stifter & Fox, 1990; Shipman & Zeman, 2001). Moreover, considerable evidence suggests that the emotional lability characteristic of aggression is shaped by coercive exchanges with parents that begin in the first five years of life (Campbell, Pierce, Moore, Marakovitz, & Newby, 1996; Cole & Zahn-Waxler, 1992; Patterson, Capaldi, & Bank, 1991). In such exchanges, parents and children escalate conflict by matching and oftentimes exceeding one another’s arousal levels (Snyder, Edwards, McGraw, Kilgore, & Holton, 1994; Snyder, Schrepferman, & St. Peter, 1997). Because this escalation often terminates aversive interactions, heightened autonomic arousal and emotional lability are negatively reinforced, increasing in frequency and intensity over time. This is troublesome given that the acquisition of self-regulatory strategies is an important developmental challenge for preschool children, and given that dyadic interactions with parents are the primary source of such socialization (Maccoby, 1992).

We have hypothesized that learned deficiencies in emotion regulation that are shaped within families through coercive processes amplify inherited impulsivity to produce CD in children who already have ADHD. In comparison, the socialization of strong emotion regulation skills may buffer at-risk children with ADHD from developing CD. These hypotheses are consistent with findings reported by Patterson, DeGarmo, and Knutson (2000) demonstrating that ADHD leads to CD only when accompanied by coercive parenting, and by behavior genetics research indicating that comorbidity of ADHD and CD is accounted for primarily by shared environmental factors (Burt, Krueger, McGue, & Iacono, 2001). Thus, when emotional and autonomic lability are shaped in children with ADHD through repeated exposure to negative reinforcement of negative affect, the development of CD is encouraged. This implies that autonomic markers of emotional lability including RSA will be responsive to psychosocial interventions that target coercive interaction patterns and promote social competence. Indeed, behavior genetics research indicates significant environmental influences on RSA (Sneider, Boomsma, van Doornan, & DeGeus, 1997). Psychosocial interventions may therefore be essential for preventing the development of ADHD to CD in children who are vulnerable due to inherited impulsivity. Moreover, for interventions to be effective, familial negative reinforcement of autonomic arousal and emotional lability must be addressed.

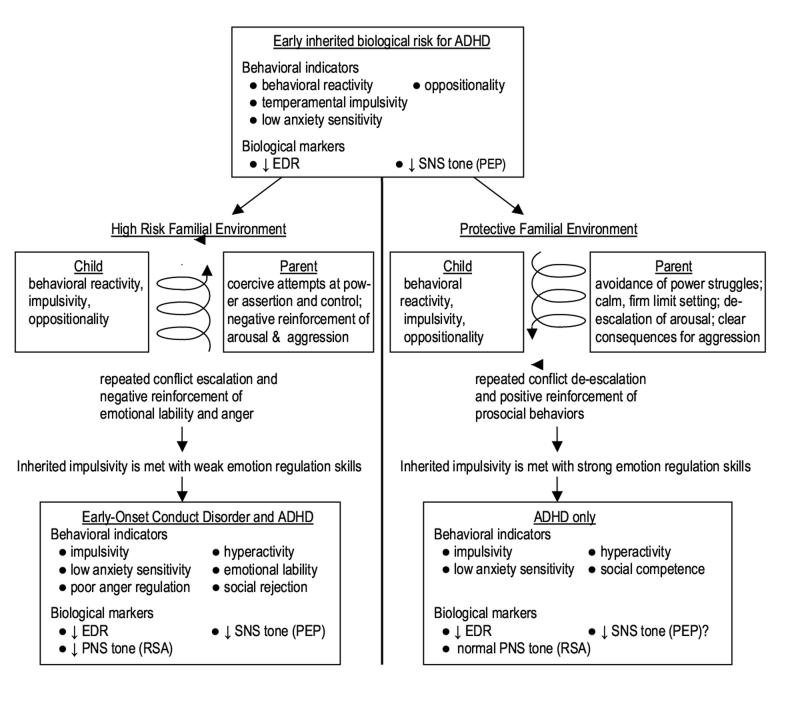

The biosocial developmental model implied by the above discussion is summarized in Figure 2. The right side of the model depicts a protective familial environment in which strong emotion regulation skills are socialized through de-escalation of arousal, positive reinforcement of prosocial behaviors, and clear consequences for aggression. Impulsive children following this pathway are protected from aggressive CD through the development of effective vagal modulation of emotion. In contrast, the left side of the model depicts a high risk familial environment in which emotional lability is socialized through negative reinforcement of arousal and aggression. Impulsive children following this pathway are at risk for aggressive conduct disorder and delinquency through the development of poor vagal modulation of emotion.

Figure 2.

Hypothesized relations between inherited biological risk for ADHD and environmental-familial risk for CD. Note that inherited impulsivity renders ADHD children at particularly high risk for future CD in the context of coercive family environments, where emotional lability is repeatedly reinforced.

Because the preschool years represent a sensitive period for the acquisition of emotion regulation and executive control (see Blair, 2002), early intervention aimed at altering coercive family processes that promote emotional lability may be may be especially important in attenuating risk for CD. It is well known that the most effective interventions for conduct problems are those that include parent training aimed at altering coercive reinforcement contingencies (Brestan & Eyberg, 1998), and that such interventions are far more effective when initiated with younger as opposed to older children (e.g., Ruma, Burke, & Thompson, 1996). Polyvagal Theory suggests a neurobiological mechanism for these findings. Children who habitually respond to social interactions with emotional lability due to histories of coercive reinforcement contingencies may never have developed adequate executive control over their emotional response patterns, reflected in deficient vagal modulation of SNS-mediated responding, which is also compromised. Newer instantiations of Polyvagal Theory (Porges, 2001) emphasize the importance of higher-order executive control over the phylogenetically newer vagal system, and specify connections between the NA and prefrontal cortex through the amygdala. It is therefore not surprising that the development of executive functions and emotion regulation are inextricably intertwined.

Conclusion

It has now been a decade since Porges (1995) first advanced Polyvagal Theory. In that time, the theory has lent coherence to a wide range of clinical observations among a diverse array of psychiatric conditions spanning both the internalizing and externalizing spectra. The theory has provided unique insights into the role of emotion dysregulation in psychopathology, and into the development of aberrant patterns of autonomic nervous system functioning in numerous clinical syndromes that before were considered unrelated. Furthermore, the theory has generated a host of descriptive insights that otherwise would not have been pursued. Our work with externalizing children and adolescents provides one such example. It is our hope that Polyvagal Theory will continue to advance our understanding of psychopathology and its development in the decade to come.

Footnotes

Both vagal branches also innervate other target organs that are not the focus of this paper. Interested readers are referred to Porges (1995, 1998, 2001) for further details.

Work on this chapter was supported by Grants F31 MH12209 and R01 MH63699 to Theodore P. Beauchaine from the National Institute of Mental Health. We express our thanks to Sharon Brenner, Jane Chipman-Chacon, Sheila Crowell, Penny Marsh, and Patrick Sylvers for their helpful contributions to this work.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the child behavior checklist/4-18 and 1991 profile. University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; Burlington, VT: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Author; Washington, DC: 1952. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Author; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Author; Washington, DC: 2000. text revision. [Google Scholar]

- Beauchaine TP. Vagal tone, development, and Gray’s motivational theory: Toward an integrated model of autonomic nervous system functioning in psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:183–214. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401002012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchaine TP. Autonomic substrates of heart rate reactivity in adolescent males with conduct disorder and/or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. In: Shohov SP, editor. Advances in Psychology Research. Vol. 18. Nova Science Publishers; New York: 2002. pp. 83–95. [Google Scholar]

- Beauchaine TP. Taxometrics and developmental psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. 2003;15:501–527. doi: 10.1017/s0954579403000270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchaine TP, Katkin ES, Strassberg Z, Snarr J. Disinhibitory psychopathology in male adolescents: Discriminating conduct disorder from attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder through concurrent assessment of multiple autonomic states. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:610–624. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.4.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchaine TP, Marsh P. Taxometric methods: Enhancing early detection and prevention of psychopathology by identifying latent vulnerability traits. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen D, editors. Developmental Psychopathology. 2nd Ed. Wiley; Hoboken, NJ: in press. [Google Scholar]

- Berntson GG, Bigger TJ, Eckberg DL, Grossman P, Kaufmann PG, Malik M, Nagaraja HN, Porges SW, Saul JP, Stone PH, van der Molen MW. Heart rate variability: Origins, methods, and interpretive caveats. Psychophysiology. 1997;34:623–648. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1997.tb02140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair C. School readiness: Integrating cognition and emotion in a neurobiological conceptualization of child functioning at school entry. American Psychologist. 2002;57:111–127. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.57.2.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce WT, Quas J, Alkon A, Smider NA, Essex MJ, Kupfer DJ. Autonomic reactivity and psychopathology in middle childhood. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;179:144–150. doi: 10.1192/bjp.179.2.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner JD, Vermetten E. Stress and development: Behavioral and biological consequences. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:473–489. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401003042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner SL, Beauchaine TP, Sylvers PD. A comparison of psychophysiological and self-report measures of behavioral approach and behavioral inhibition. Psychophysiology. 2005;42:108–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2005.00261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brestan EV, Eyberg SM. Effective psychosocial treatments of conduct-disordered children and adolescents: 29 years, 82 studies, and 5,272 kids. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1998;27:180–189. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2702_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt SA, Krueger RF, McGue M, Iacono WG. Sources of Covariation among attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, and conduct disorder: The importance of shared environment. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:516–525. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.110.4.516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush G, Frazier JA, Rauch SL, Seidman LJ, Whalen PJ, Jenike MA, Rosen BR, Biederman J. Anterior cingulate cortex dysfunction in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder revealed by fMRI and the counting Stroop. Biological Psychiatry. 1999;45:1542–1552. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00083-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD. Cardiac vagal tone indices of temperamental reactivity and behavioral regulation in young children. Developmental Psychobiology. 1997;31:125–135. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2302(199709)31:2<125::aid-dev5>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB, Pierce EW, Moore G, Marakovitz S, Newby K. Boys’ externalizing problems at elementary school: Pathways from early behavior problems, maternal control, and family stress. Development and Psychopathology. 1996;8:836–851. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB, Shaw DS, Gilliom M. Early externalizing behavior problems: Toddlers and preschoolers at risk for later maladjustment. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12:467–488. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400003114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, ZahnWaxler C. Emotional dysregulation in disruptive behavior disorders. In: Cicchetti D, Toth SL, editors. Developmental perspectives on depression: Vol. 4. Rochester symposium on developmental psychopathology. University of Rochester Press; Rochester, NY: 1992. pp. 173–209. [Google Scholar]

- Crowell S, Beauchaine TP, Gatzke-Kopp L, Sylvers P, Mead H. Autonomic correlates of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and oppositional defiant disorder in preschool children. 2004. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowell S, Beauchaine TP, McCauley E, Smith C. Autonomic and serotonergic correlates of parasuicidal behavior in adolescents. Development and Psychopathology. doi: 10.1017/s0954579405050522. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delameter AM, Lahey BB. Psychophysiological correlates of conduct problems and anxiety in hyperactive and learning-disabled children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1983;11:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00912180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Witte Ph., Pinto E, Ansseau M, Verbanck P. Alcohol and withdrawal: From animal research to clinical issues. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2003;27:189–197. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(03)00030-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donzella B, Gunnar MR, Krueger WK, Alwin J. Cortisol and vagal tone responses to competitive challenge in preschoolers: Associations with temperament. Developmental Psychobiology. 2000;37:209–220. doi: 10.1002/1098-2302(2000)37:4<209::aid-dev1>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durston S, Tottenham NT, Thomas KM, Davidson MC, Eigsti I-M, Yang Y, Ulug AM, Casey BJ. Differential patterns of striatal activation in young children with and without ADHD. Biological Psychiatry. 2003;53:871–878. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01904-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Murphy B, Maszk P, Smith M, Karbon M. The role of emotionality and regulation in children’s social functioning: A longitudinal study. Child Development. 1995;66:1360–1384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M, Harger J, Whitson SM. Exposure to interparental conflict and children’s adjustment and physical health: The moderating role of vagal tone. Child Development. 2001;72:1617–1636. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabes RA, Eisenberg N, Eisenbud L. Behavioral and physiological correlates of children’s reactions to others in distress. Developmental Psychology. 1993;29:655–663. [Google Scholar]

- Fabes RA, Eisenberg N, Karbon N, Troyer D, Switzer G. The relations of children’s emotion regulation to their vicarious emotional responses and comforting behaviors. Child Development. 1994;65:1678–1693. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox NA, Field TM. Individual differences in preschool entry behavior. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 1989;10:527–540. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman BH, Thayer JF. Autonomic balance revisited: Panic anxiety and heart rate variability. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1998a;44:133–151. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(97)00202-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman BH, Thayer JF. Anxiety and autonomic flexibility: A cardiovascular approach. Biological Psychology. 1998b;47:243–263. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0511(97)00027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadow KD, Sprafkin J. Child Symptom Inventory 4 norms manual. Checkmate Plus; Stony Brook, New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Gadow KD, Sprafkin J. Adolescent Symptom Inventory 4 norms manual. Checkmate Plus; Stony Brook, New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- George DT, Nutt DJ, Walker WV, Porges SW, Adinoff B, Linnoila M. Lactate and hyperventilation substantially attenuate vagal tone in normal volunteers: A possible mechanism of panic provocation? Archives of General Psychiatry. 1989;46:153–156. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810020055009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM, Katz LF. Children’s emotional reactions to stressful parent-child interactions: The link between emotion regulation and vagal tone. Marriage and the Family Review. 2002;34:265–283. [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA. The psychophysiological basis of introversion-extroversion. Behavior Research and Therapy. 1970;8:249–266. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(70)90069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA. The psychology of fear and stress. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA, McNaughton N. The neuropsychology of anxiety. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, Levenson RW. Emotion elicitation using films. Cognition & Emotion. 1995;9:87–108. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen AL, Johnsen BH, Thayer JF. Vagal influence on working memory and attention. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2003;48:263–274. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8760(03)00073-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayano J, Sakakibara Y, Yamada A, Yamada M, Mukai S, Fujinami T, Yokoyama K, Watanabe Y, Takata K. Accuracy of assessment of cardiac vagal tone by heart rate variability in normal subjects. American Journal of Cardiology. 1991;67:199–204. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(91)90445-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houts AC. Discovery, invention, and the expansion of the modern Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. In: Beutler LE, Malik ML, editors. Rethinking the DSM. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2002. pp. 17–65. [Google Scholar]

- Iaboni F, Douglas V, Ditto B. Psychophysiological response of ADHD children to reward and extinction. Psychophysiology. 1997;34:116–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1997.tb02422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz LF, Gottman JM. Vagal tone protects children from marital conflict. Development & Psychopathology. 1995;7:83–92. [Google Scholar]

- Katz LF, Gottman JM. Buffering children from marital conflict and dissolution. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1997;26:157–171. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2602_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein DN, Riso LP. Psychiatric disorders: Problems of boundaries and comorbidity. In: Costello CG, editor. Basic issues in psychopathology. Guilford Press; New York: 1993. pp. 19–66. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Hicks BM, Patrick CJ, Carlson SR, Iacono WG, McGue M. Etiologic connections among substance dependence, antisocial behavior, and personality: Modeling the externalizing spectrum. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:411–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laakso A, Wallius E, Kajander J, Bergman J, Eskola O, Solin O, Ilonen T, Salokangas RKR, Syvälahti E, Hietala J. Personality traits and striatal dopamine synthesis capacity in healthy subjects. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:904–910. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.5.904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laine T, Ahonen A, Rasanen P, Tiihonen J. Dopamine transporter density and novelty seeking among alcoholics. Journal of Addictive Disease. 2001;20:95–100. doi: 10.1300/j069v20n04_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyonfields JD, Borkovec TD, Thayer JF. Vagal tone in generalized anxiety disorder and the effects of aversive imagery and worrisome thinking. Behavior Therapy. 1995;26:457–466. [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby EE. The role of parents in the socialization of children. Developmental Psychology. 1992;28:1006–1017. [Google Scholar]

- McNaughton N, Corr PJ. A two-dimensional neuropsychology of defense: fear/anxiety and defensive distance. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2004;28:285–305. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mead HK, Beauchaine TP, Brenner SL, Crowell S, Gatzke-Kopp L, Marsh P. Autonomic response patterns to reward and negative mood induction among children with conduct disorder, depression, and both psychiatric conditions; annual meeting of the Society for Psychophysiological Research; Santa Fe, NM. 2004; Poster presented at the. [Google Scholar]

- Mezzacappa E, Tremblay RE, Kindlon D, Saul JP, Arseneault L, Seguin J, Pihl RO, Earls F. Anxiety, antisocial behavior, and heart rate regulation in adolescent males. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1997;38:457–469. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nader K, Bechara A, van der Kooy D. Neurobiological constraints on behavioral models of motivation. Annual Review of Psychology. 1997;48:85–114. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Capaldi D, Bank L, Pepler D. An early starter model for predicting delinquency. In: Rubin KH, editor. The development and treatment of childhood aggression. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1991. pp. 139–168. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, DeGarmo DS, Knutson N. Hyperactive and antisocial behaviors: Comorbid or two points in the same process? Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12:91–106. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400001061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pine DS, Wasserman G, Coplan J, Fried J, Huang Y, Kassir S, Greenhill L, Shaffer D, Parsons B. Platelet serotonin 2A (5-HT2A) receptor characteristics and parenting factors for boys at risk for delinquency: A preliminary report. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1996;153:538–544. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.4.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pine DS, Wasserman GA, Miller L, Coplan JD, Bagiella E, Kovelenku P, Myers MM, Sloan RP. Heart period variability and psychopathology in urban boys at risk for delinquency. Psychophysiology. 1998;35:521–529. doi: 10.1017/s0048577298970846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popper KR, Miller D. Popper selections. Princeton University Press; Princeton, NJ: 1985. The aim of science; pp. 162–170. Original work published in 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Porges SW. Orienting in a defensive world: Mammalian modifications of our evolutionary heritage. A polyvagal theory. Psychophysiology. 1995;32:301–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1995.tb01213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porges SW. Emotion: An evolutionary by-product of the neural regulation of the autonomic nervous system. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1997;807:62–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb51913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porges SW. Love: An emergent property of the mammalian autonomic nervous system. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1998;23:837–861. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(98)00057-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porges SW. The polyvagal theory: Phylogenetic substrates of a social nervous system. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2001;42:123–146. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8760(01)00162-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porges SW. Social engagement and attachment: A phylogenetic perspective. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2003;1008:31–47. doi: 10.1196/annals.1301.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raine A, Venables PH, Dalais C, Mellingen K, Reynolds C, Mednick SA. Early educational and health enrichment at age 3-5 years is associated with increased autonomic and central nervous system arousal and orienting at age 11 years: Evidence from the Mauritius Child Health Project. Psychophysiology. 2001;38:254–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rechlin T, Weis M, Spitzer A, Kaschka WP. Are affective disorders associated with alterations of heart rate variability? Journal of Affective Disorders. 1994;32:271–275. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(94)90091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottenberg J, Wilhelm FH, Gross JJ, Gotlib IH. Vagal rebound during resolution of tearful crying among depressed and nondepressed individuals. Psychophysiology. 2003;40:1–6. doi: 10.1111/1469-8986.00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruma PR, Burke RV, Thompson RW. Group parent training: Is it effective for children of all ages? Behavior Therapy. 1996;27:159–169. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt LA, Fox NA, Schulkin J, Gold PW. Behavioral and psychophysiological correlates of self-presentations in temperamentally shy children. Developmental Psychobiology. 1999;35:119–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz ED, Perry BD. The post-traumatic response in children and adolescents. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 1994;17:311–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sneider H, Boomsma DI, vanDoornen LJP, DeGeus EJC. Heritability of respiratory sinus arrhythmia: Dependency on task and respiration rate. Psychophysiology. 1997;34:317–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1997.tb02402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherwood A, Allen MT, Fahrenbert J, Kelsey RM, Lovallo WR, van Doornen LJP. Committee report: Methodological guidelines for impedance cardiography. Psychophysiology. 1990;27:1–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1990.tb02171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherwood A, Allen MT, Obrist PA, Langer AW. Evaluation of beta-adrenergic influences on cardiovascular and metabolic adjustments to physical and psychological stress. Psychophysiology. 1986;23:89–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1986.tb00602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipman KL, Zeman J. Socialization of children’s emotion regulation in mother-child dyads: A developmental psychopathology perspective. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:317–336. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401002073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan RP, Shapiro PA, Bigger JT, Bagiella M, Steinman RC, Gorman JM. Cardiac autonomic control and hostility in healthy subjects. American Journal of Cardiology. 1994;74:298–300. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(94)90382-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder J, Edwards P, McGraw K, Kilgore K, Holton A. Escalation and reinforcement in mother-child conflict: Social processes associated with the development of physical aggression. Development and Psychopathology. 1994;6:305–321. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder J, Schrepferman L, St. Peter C. Origins of antisocial behavior: Negative reinforcement and affect dysregulation of behavior as socialization mechanisms in family interaction. Behavior Modification. 1997;21:187–215. doi: 10.1177/01454455970212004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stifter CA, Fox NA. Infant reactivity: Physiological correlates of newborn and 5-month temperament. Developmental Psychology. 1990;26:582–588. [Google Scholar]

- Suess PA, Porges SW, Plude DJ. Cardiac vagal tone and sustained attention in school-age children. Psychophysiology. 1994;31:17–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1994.tb01020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson JM, Castellanos FX. Biological bases of ADHD—neuroanatomy, genetics, and pathophysiology. In: Jensen PS, Cooper JR, editors. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Civic Research Institute; Kingston, NJ: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Thayer JF, Friedman BH, Borkovec TD. Autonomic characteristics of generalized anxiety disorder and worry. Biological Psychiatry. 1996;39:255–266. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00136-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaidya CJ, Austin G, Kirkorian G, Ridlehuber HW, Desmond JE, Glover GH, Gabrieli JDE. Selective effects of methylphenidate in attention deficit hyperactivity disorders: A functional magnetic resonance study. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1998;95:14494–14499. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Buuse M. Role of the mesolymbic dopamine system in cardiovascular homeostasis: Stimulation of the ventral tegmental area modulates the effect of vasopressin in conscious rats. Clinical Experimental Pharmacology and Physiology. 1998;25:661–668. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1998.tb02273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber EJM, van der Molen MW, Molenaar PCM. Heart rate and sustained attention during childhood: Age changes in anticipatory heart rate, primary bradycardia, and respiratory sinus arrhythmia. Psychophysiology. 1994;31:164–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1994.tb01036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeragani VK, Pohl R, Balon R, Ramesh C, Glitz D, Weinberg P, Merlos B. Effect of imipramine treatment on heart rate variability measures. Biological Psychiatry. 1992;26:27–32. doi: 10.1159/000118892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeragani VK, Pohl R, Berger R, Balon R, Ramesh C, Glitz D, Srinivasan K, Weinberg P. Decreased heart rate variability in panic disorder patients: a study of power-spectral analysis of heart rate. Psychiatry Research. 1993;46:89–103. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(93)90011-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]