Abstract

The role of auditory circuitry is to decipher relevant information from acoustic signals. Acoustic parameters used by different insect species vary widely. All these auditory systems, however, share a common transducer: tympanal organs as well as the Drosophila flagellar ears use chordotonal organs as the auditory mechanoreceptors. We here describe the central neural projections of the Drosophila Johnston’s organ (JO). These neurons, which represent the antennal auditory organ, terminate in the antennomechanosensory center. To ensure correct identification of these terminals we made use of a β-galactosidase-expressing trans-gene that labels JO neurons specifically. Analysis of these projection pathways shows that parallel JO fibers display extensive contacts, including putative gap junctions. We find that the synaptic boutons show both chemical synaptic structures as well as putative gap junctions, indicating mixed synapses, and belong largely to the divergent type, with multiple small postsynaptic processes. The ultrastructure of JO fibers and synapses may indicate an ability to process temporally discretized acoustic information.

Indexing terms: auditory fibers, bouton, cholinergic neuron, chordotonal organ, gap junction, mechanosensation, septate junction, X-gal

Detailed physiological analyses of identified interneurons in insect auditory circuits has enlightened mechanisms for extracting diverse kinds of species-relevant information (Pollack, 1998, 2000; Stumpner and von Helversen, 2001; Stumpner, 2002; Hennig et al., 2004). Some insects show exquisite direction-sensitivity, perhaps epitomized by the parasitoid Dipteran Ormia ochracea (Robert et al., 1996, 1998), which finds its cricket hosts by localizing their calling songs. Tonotopic frequency discrimination, such as along the cochlea in higher vertebrates, can be found in the crista acoustica of many insects such as katydids (Oldfield, 1982; Oldfield et al., 1986; Stölting and Stumpner, 1998). Most insects perform discrimination of temporal patterns. For example, the courtship songs in the Drosophila species contain pulse songs that have species-specific interpulse intervals (IPI). These IPI differences and their modulation appear to provide species information for female choice of conspecific mates (Bennet-Clark and Ewing, 1969; Kyriacou and Hall, 1986, 1994; Hall, 1994; Ritchie et al., 1999). Temporal and directional aspects of cricket acoustic processing have been extensively studied (Pollack, 2000; Hedwig and Poulet, 2004; Tunstall and Pollack, 2005). In a more complicated courtship ritual, some katydids perform and decipher precisely timed duets (e.g., Tauber and Pener, 2000; Tauber, 2001). All these functions are achieved by acoustic processing and the parallels between insects and vertebrates suggest that insect auditory systems may provide useful models for vertebrate acoustic processing.

A fascinating feature of vertebrate ears is the production of spontaneous or induced otoacoustic emissions, a possible by-product of hair cell electromotility (Brownell et al., 1985) or of conformational changes in myosin (Manley and Gallo, 1997) or transduction channel molecules (Choe et al., 1998). Interestingly, distortion-product otoacoustic emissions have been reported from the tympanal organs (ears) of grasshoppers and noctuid moths (Coro and Kössl, 1998; Kössl and Boyan, 1998a,b). Even in the mosquito and in Drosophila, which use their antennae as flagellar auditory organs, spontaneous activity has been recorded that may be the equivalent of otoacoustic emissions (Göpfert and Robert, 2001a, 2003; Robert and Göpfert, 2002; Göpfert et al., 2005).

The presence of chordotonal auditory organs in a wide variety of segmental and anatomical locations in different insect species (Hoy, 1998; Yack, 2004) has led to the notion that any preexisting (presumably proprioceptive) chordotonal organ could be specialized for auditory function (Meier and Reichert, 1990; Yack and Fullard, 1990; Boyan, 1998; van Staaden and Römer, 1998; Prier and Boyan, 2000; Stumpner and von Helversen, 2001). This argues that the incredible variety of anatomical locations of ears could arise by relatively few changes in gene regulation to specialize one or another of the chordotonal organs for acoustic stimuli. Of course, chordotonal organs in each location project to a region in the CNS within or close to the body segment that carries them. Thus, an evolutionary change in ear location would require either activation of a new circuit for acoustic processing in that segment, or modification of a preexisting circuit. It is likely that at least a portion of the wide variation of behavioral responses has come about by a combination of these explanations.

While the idea that regulatory changes in preexisting developmental programs can effect such changes in ear location is plausible and compelling, the genetic program that executes these developmental changes is not well understood. If true, this idea has important implications for adaptations in the CNS that must coevolve for the processing of the auditory signals. Indeed, neurons from auditory organs in different segments project their axons to segmentally homologous locations in the CNS (Boyan, 1998; Prier and Boyan, 2000). Furthermore, Drosophila homeotic mutations of the Antennapedia gene, which transform the antenna into a leg, show projection patterns from this transformed antennal leg into the antennal regions of the brain (Stocker et al., 1976; Stocker, 1979; Stocker and Lawrence, 1981). The morphological transformations are most complete at the distal ends of the appendage, and it is not clear whether the abnormalities in the antennal regions in these mutants arise from transformation of the brain region, or simply as a secondary consequence of the fact that the complement and pattern of sensory neurons is altered in the periphery by the mutation. In any case, development of circuitry specialized for auditory processing may arise by activation of a similar evolutionarily conserved genetic program for CNS development.

To begin to understand genetic programs underlying the development of auditory circuits, we have sought to characterize the auditory system of a genetically tractable insect, Drosophila melanogaster. By studying mutations that disrupt auditory processing, we hope to elucidate the genetic control of Johnston’s organ (JO) development, its central projections, and the neural circuit responsible for auditory processing. To this end, we designed a genetic screen to identify mutations that disrupt a behavioral auditory response (Eberl et al., 1997). In this screen, 15 mutations were recovered. Using our electrophysiological recording preparation for hearing in this species, we found that two of these mutations (beethoven5P1 and 5D10) have peripheral defects (Eberl et al., 2000; see also Caldwell and Eberl, 2002). The two additional mutations (5G10, renamed pirouette, and 5N18) are associated with brain degeneration (Eberl et al., 1997). This leaves several mutations that could affect the JO neuronal projections to the CNS or other aspects of the neural circuit. Here we describe the ultrastructural morphology of the wildtype JO projections into the antenno-mechanosensory center (AMC) in the subesophageal ganglion of the brain. This will serve as a basis for future investigations into the effects of auditory behavior mutants in Drosophila, and into evolutionary mechanisms in acoustic processing.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Drosophila strains

Flies were maintained at 25°C on a cornmeal, yeast, agar medium. All experiments were performed on the y w; H{Lw2, w+mC}J21.17 strain, henceforth referred to as J21.17. This strain carries an insertion of the hobo enhancer trap transposable element (Smith et al., 1993) at polytene chromosome position 52A and shows very specific expression of the lacZ reporter gene in at least a subset of JO neurons (Sharma et al., 2002). For our studies, both male and female flies were used; however, because we saw no differences in the structures reported, we do not distinguish between the sexes in our presentation of individual figures.

X-gal staining

To stain for β-galactosidase activity, fly heads were removed in fixative (2.5% glutaraldehyde and 2% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, PB, pH 7.4). The head cuticle was opened dorsally and the proboscis was removed to facilitate penetration of solutions. The heads were fixed for 5 minutes, rinsed in PB, and stained in X-gal staining solution (6.85 mM Na2HPO4, 3.15 mM NaH2PO4, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 3.1 mM K3Fe(III)(CN)6, 3.1 mM K4Fe(II)(CN)6, 0.3% Triton X-100). After staining, heads were rinsed in PB and the brain and antennae were dissected and mounted for imaging on an Olympus BX51 compound microscopy fitted with an RT Spot-Slider digital camera (Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI).

Electron microscopy

For electron microscopy, heads were fixed and stained with X-gal as above. After staining the heads were further fixed overnight at 4°C in the same fixative as above, rinsed in PB, postfixed in 1% OsO4 for 1 hour, then dehydrated and processed for embedding in Epon 812. Ultrathin sections (75 nm) were stained with aqueous uranyl acetate and lead citrate and examined with a Hitachi 7000 electron microscope. Our observations are based on examination of 12 specimens.

RESULTS

X-gal labeling for electron microscopy

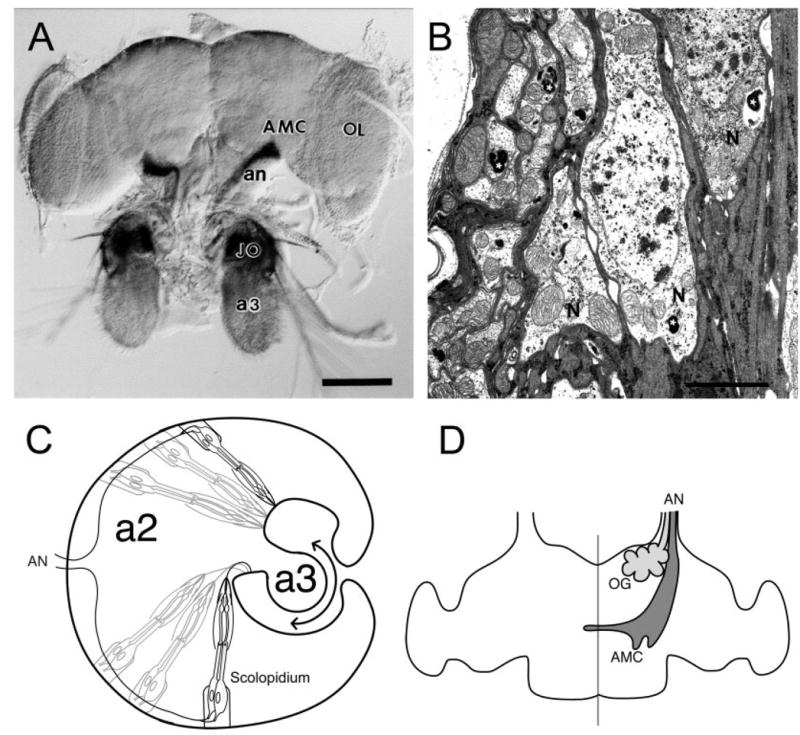

In the past, it has been difficult to perform ultrastructural studies on specific neurons in the Drosophila brain neuropil because it is often problematic to identify specific axon terminals unequivocally. To circumvent this problem, we made use of an enhancer trap strain, J21.17, which expresses β-galactosidase in JO neurons (Sharma et al., 2002; Fig. 1). This JO neuron expression is so specific that even if the tissue is greatly overstained, no other neurons in the brain are stained (data not shown). The blue X-gal reaction product is a precipitate in the cytoplasm of cells expressing the β-galactosidase reporter. Because this product is electron-dense, it can be detected at the EM level. Figure 1B shows an electron micrograph of JO neurons in the periphery showing the stain precipitate (white asterisks) in organelles in at least two of the three neuronal cell bodies. On the left side of the figure, stained organelles are also seen (white asterisks) in transverse sections of JO axons. In axons, the β-galactosidase enzyme is transported in membranous organelles, etc. This sequestered localization of the stain is useful because the identity of expressing terminals is unequivocal and, in addition, the synaptic structures remain unobscured.

Fig. 1.

Expression of J21.17 in the Drosophila auditory system. A: Frontal view of whole-mounted J21.17 brain, stained with X-gal. The antennae remain attached. The J21.17 enhancer trap strain shows strong staining with the β-galactosidase reporter in JO neurons (JO), located in the second antennal segment. The third antennal segment (a3) is unstained. Stained antennal nerve (an) projects to the antenno-mechanosensory center (AMC) of the brain. B: Electron micrograph of X-gal-stained a2, showing cell bodies of three JO neurons (N). Labeled cisterni in two of these neurons are indicated with white asterisks. Along the left-hand side of the figure cross-sectional profiles of several JO axons are seen; two examples of labeled organelles in these axons are indicated by white asterisks. In this and following figures, black asterisks are used to label selected JO fibers, while white asterisks are placed on stained organelles themselves. C: Diagram of the arrangement of JO scolopidia in a2. The apical end of each scolopidium is attached to the a2/a3 joint such that sound-induced oscillations of a3 (double-headed arrow) result in changes in scolopidial length. Mechanotransduction in the JO neurons results in action potentials along the JO axons, which join the antennal nerve (AN) as it approaches the head cavity. (Modified from Caldwell and Eberl, 2002). D: Drawing of antennal nerve (AN) projections into the brain. Projections from a3 primarily enter the olfactory glomeruli (OG) and are composed of small diameter fibers (light gray), while the JO neurons project to the antennomechanosensory center (AMC) via their larger diameter axons (dark gray). (Adapted from Stocker and Lawrence, 1981). OL, optic lobe. Scale bars =100 μm in A; 1.5 μm in B.

Anatomy of the antennal nerve

The structure and operation of the Drosophila JO has been described in detail by us and others (e.g., Uga and Kuwabara, 1965; Eberl, 1999; Göpfert and Robert, 2001b, 2002; Caldwell and Eberl, 2002; Jarman, 2002; Todi et al., 2004). Briefly, near-field acoustic stimulation results in rotation of the third antennal segment (a3) about its joint with the second segment (a2) (Fig. 1C). JO resides in a2, and comprises between 150 and 200 scolopidia, most of which contain two neurons, although perhaps 15% are triply innervated. Thus, on the order of 400 neurons are present in each JO. Axons of these neurons join those of the olfactory sensilla in the antennal nerve from a3, as it transits a2 en route to the brain. The focus of the current study is on the structure of the JO axons in the antennal nerve and their terminals in the AMC.

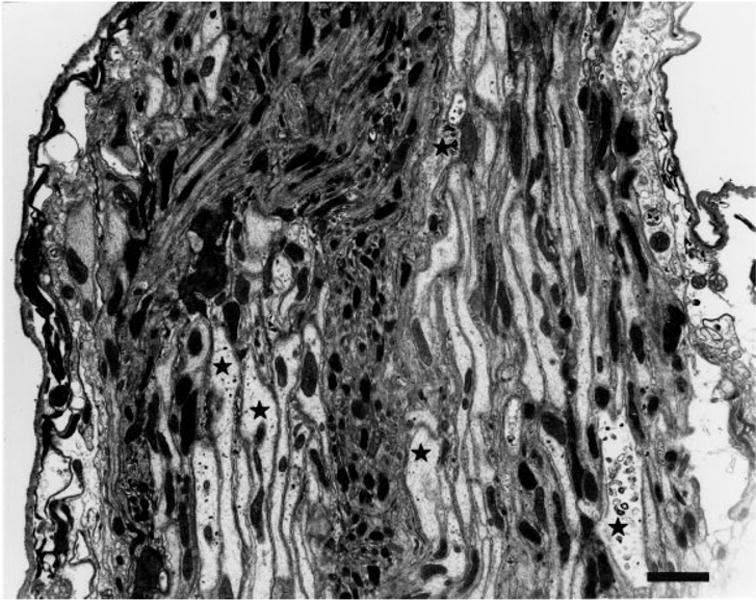

The Drosophila antennal nerve has previously been described in silver-stained sections (Power, 1946) as containing thin fibers and thick fibers, and this is confirmed by electron microscopy (this work and Stocker, 1979). The thin fibers, representing primarily olfactory neuron fibers from the third antennal segment, defasciculate from the nerve upon entry into the brain to innervate the olfactory glomeruli (Power, 1946; Strausfeld, 1976; Stocker, 1979, 1994). The large-diameter fibers, representing JO neurons, continue posteriorly through the brain to project in the antenno-mechanosensory center of the deuterocerebrum (Power, 1946; Strausfeld, 1976; Stocker, 1979; Stocker and Lawrence, 1981; Lienhard and Stocker, 1991) (Figure 1D). A section through the antennal nerve (Fig. 2) confirms the presence of two axon size classes. The large diameter fibers are on the order of 1–2 μm across and are identified as JO fibers because they are labeled with X-gal. Stocker (1979) described a typical arrangement of four fiber areas in the nerve and counted about 1,800 axons in the wildtype antennal nerve, with about 1,140 of them originating in a3 as determined by Wallerian degeneration. The remaining axons include both JO fibers and axons from bristle organs on a2. In general, the small-diameter fibers in the antennal nerve tend to be associated with one another on the opposite side of the nerve from thick fibers, but this modality-specific sequestered arrangement is not strict. This is consistent with the report of Stocker (1979). Indeed, Power (1946) and Strausfeld (1976) mention decussations of the JO axons within the antennal nerve. The small, unlabeled fibers are more electron-dense than the large fibers (Fig. 2). Within the large fibers, regularly spaced longitudinal microtubules are evident; presumably these are used for transporting organelles and other cargoes between the cell bodies and the synaptic terminals.

Fig. 2.

Electron micrograph of the sectioned antennal nerve. The antennal nerve consists of two types of fibers. These include large-diameter fibers (asterisks identify some of the X-gal-containing fibers) labeled with X-gal reaction product appearing as a dark precipitate (not easily portrayed in this low-magnification image) and small diameter fibers. Scale bar = 1 μm.

As the nerve passes through the anterior part of the brain, the JO fibers remain in close contact with each other (Fig. 3A). On approach to the AMC, many JO fibers begin to dissociate from one another, as seen in transverse sections (Fig. 3B), while others remain associated in small bundles (Fig. 3C). Many labeled membranous organelles are present in these axons at this level in the brain. Shanbhag et al. (1992) describe a peripheral glomerular structure formed by lateral axonal extensions of the Drosophila femoral chordotonal neurons. Despite extensive contacts between JO fibers, we see no evidence of such a glomerular structure along the antennal nerve in the mechanosensory track.

Fig. 3.

Fibers of the antennal nerve within the brain. A: Labeled fibers (asterisks) enter the brain as a bundle. The electron-dense X-gal reaction product (shown at higher magnification in Figs. 4–6) is enclosed in membranous organelles such as vacuoles, cisternae, and tubule-vesicular elements. B: Transverse section through large-diameter fibers (asterisks) in the AMC. C: Longitudinally sectioned JO axons (asterisks) carry solid X-gal reaction product. Distributed parallel microtubules follow along the labeled fibers. Scale bars =0.5 μm in A; 1 μm in B,C.

JO axon terminals in the AMC

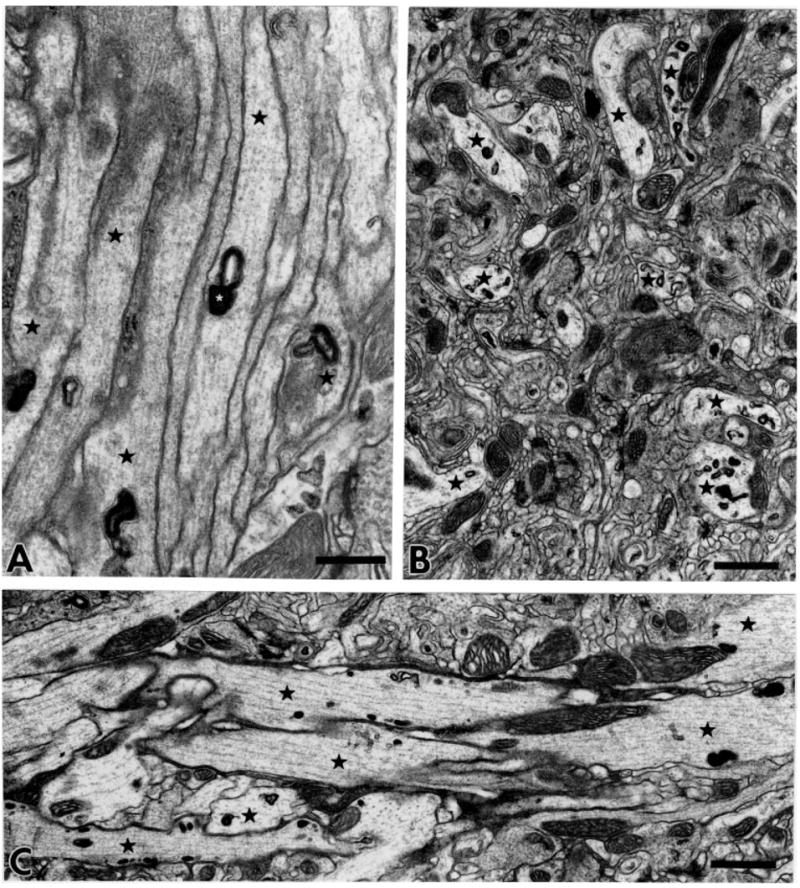

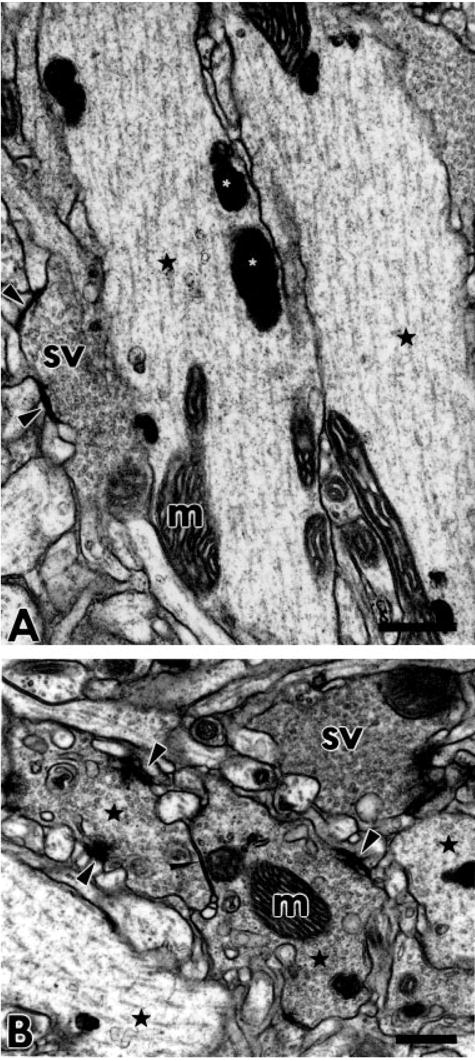

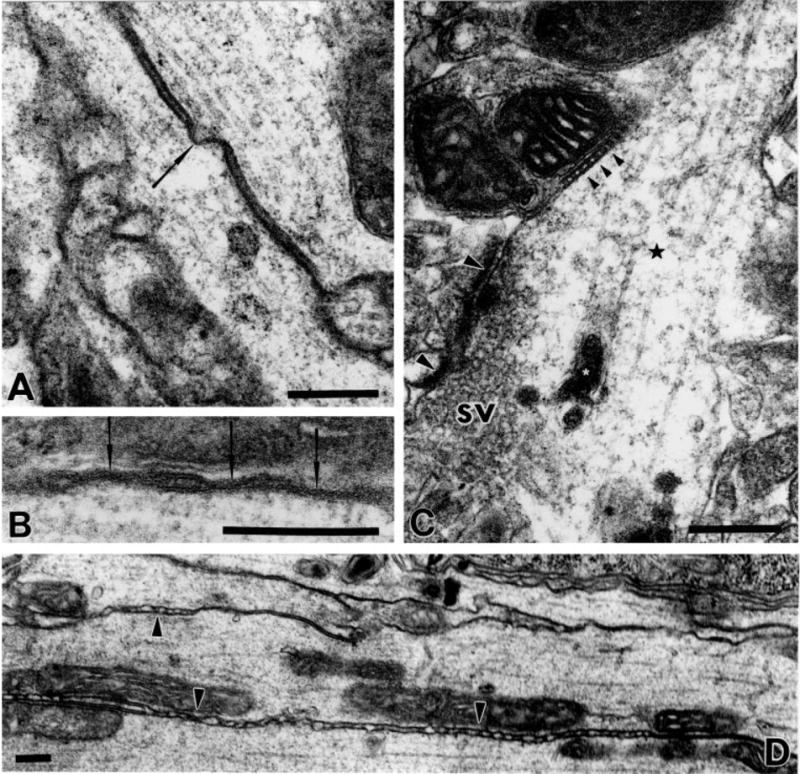

At high magnification, regularly spaced microtubules are seen in the JO fibers in the AMC (Fig. 4A). Boutons are located not only at the extreme termini of the axons; many appear en passant as side compartments along the length of the fiber. Large mitochondria are almost always present in the vicinity of the boutons, often filling a third or more of the bouton space. The boutons are densely packed with apparently homogeneous vesicles that are always small, spherical, and clear (Figs. 4B, 5). These vesicles are 35 ± 5 nm in diameter. This is consistent with the sizes of vesicles previously seen in other Drosophila cholinergic neurons such as the projection neurons that synapse onto the Kenyon cells of the mushroom body calyces (Yusuyama et al., 2002). It is common to see adjacent boutons connected with septate junctions and other types of cell contacts (Fig. 4B). Also at these boutons there are characteristic presynaptic densities and even T-shaped synaptic docking sites at the junctions with postsynaptic structures. The intercellular space between pre- and postsynaptic membranes, the synaptic cleft, at these sites is about 20 nm, which is characteristic for chemical synapses. In some cases there is evidence of gap junction-like contacts between pre- and postsynaptic structures (Figs. 5, 6A). These gaps are approximately 2–4 nm, as is characteristic of invertebrate gap junctions (Shimohigashi and Meinertzhagen, 1998; Blagburn et al., 1999). On this morphological basis we will refer to these contacts as gap junctions, with the caveat that data on electrical transmission are required to confirm that they actually function as electrical synapses.

Fig. 4.

JO fibers in the AMC. A: Longitudinally sectioned JO axons (black asterisks) with a large number of regularly distributed microtubules. The electron-dense product of X-gal staining (white asterisks) and mitochondria (m) occur along the microtubules. One of the fibers has a compartment filled with small clear spherical synaptic vesicles (sv). Synaptic active zones, docking sites for synaptic vesicles, are indicated with black arrowheads. B: Three cross-sectioned JO synaptic boutons accumulate large numbers of small clear spherical vesicles (sv). Black asterisks indicate selected fibers identifiable as JO fibers based on X-gal reaction product content. While no X-gal product is visible in the bouton labeled with “sv,” we saw stained organelles in the axon contiguous with this bouton in neighboring sections. One of the boutons containing X-gal reaction product includes a large mitochondrion (m) and makes septate junctions with another bouton (narrow arrowhead). Wider arrowheads indicate active zones of synapses. Scale bars = 0.5 μm.

Fig. 5.

JO synaptic bouton with multiple divergent-type synaptic junctions. Synaptic junctions (arrowheads) are with multiple small postsynaptic structures. The bouton is packed full of small clear spherical vesicles and a large mitochondrion (m) is present. Between these chemical synapses we see putative gap junctions (arrow). An X-gal-labeled cisternum is indicated with a white asterisk. Scale bar = 0.25 μm.

Fig. 6.

Various types of cell contacts in the AMC. A: Putative gap junction (arrow) between two longitudinally sectioned JO axons. B: Higher-magnification view of putative gap junctions (arrows) between JO fibers, so-called because of the closely apposed membranes with gaps on the order of 2–4 μm. The X-gal-stained organelles in both axons have been cropped from this image in favor of presenting the high-magnification view. C: Clear spherical vesicles (sv) accumulated close to the active zones of chemical synapse with four postsynaptic structures (synaptic tetrad, at and between large arrowheads). A septate junction (small arrowheads) is seen nearby. White asterisks indicate X-gal-labeled organelles. D: Extensive irregular contact (arrowheads) between parallel JO fibers in the AMC. Scale bars = 0.25 μm.

The synaptic contacts appear to be largely of the divergent multiple-contact type, an arrangement commonly seen in insect central synapses (discussed by Meinertzhagen, 1996). Thus, each bouton makes contact with multiple postsynaptic compartments, each significantly smaller than the presynaptic structure. For example, the synaptic region highlighted in Figure 6C has at least four distinct postsynaptic structures, a synaptic tetrad. The bouton in Figure 5 is associated with several more dendritic processes, as are each of the boutons in Figure 4B. It is not possible to determine, without a systematic serial reconstruction, whether all the postsynaptic structures contacting a given bouton are dendrites of the same postsynaptic neuron or of many different postsynaptic neurons.

Besides the synaptic contacts of JO axon terminals, we see extensive irregular associations between the JO axons along their length (Fig. 6C). These contacts are characterized by frequent punctate adhesions of the two membranes. These adhesions occur at ~20–30 contacts per μm but the intercontact intervals are very irregular (see Fig. 6C). Regions of such contacts are also interspersed with segments of septate junctions, and putative gap junctions can also be seen between adjacent JO fibers. From our material it is unclear whether glia are present in these regions, nor whether there are close associations or contacts with glia.

DISCUSSION

While the basic developmental events and the transduction processes in the sensory cells are at least partially conserved between chordotonal organs and the vertebrate inner ear, the downstream circuitry is much less likely to be conserved (Eberl, 1999; Fritzsch et al., 2000; Jarman, 2002; Boekhoff-Falk, 2005). Within vertebrates, although the basic architecture of the auditory cortex is largely conserved, there are major differences in the detailed assembly and circuitry because of the diversity of acoustic signals, the species-specific relevance of different sounds, and the different types of behavior influenced by sounds. These variations extend even more widely when invertebrates are included in the comparison.

Topics in insect auditory processing have recently been reviewed (Pollack, 1998, 2000; Pollack and Imaizumi, 1999; Stumpner and von Helversen, 2001). Most vertebrate capabilities of auditory processing can also be found in insects. Some insects distinguish certain spatial and temporal aspects of acoustic signals with acuity that rivals vertebrate auditory systems. In Drosophila, females have been shown to behaviorally discriminate species-specific parameters of the courtship song (Kyriacou and Hall, 1986; Ritchie et al., 1999). How they accomplish the auditory processing for this behavior has not been previously studied at the circuit level.

The projections of Drosophila JO neurons have previously been described at the light microscope level. Studies as early as 1946 (Power), using Cajal’s silver staining technique, have recognized at least two distinct projection areas from antennal neurons, namely, the olfactory fibers projecting to the antennal glomeruli in the anterior region of the brain, and the JO fibers (these were erroneously called “long olfactory fibers” by Power) into the AMC in the deuterocerebrum. This has been confirmed and elaborated (Stocker and Lawrence, 1981) using cobalt backfills together with “Wallerian degeneration.” This organization in Drosophila is similar to that described for Musca domestica in Strausfeld’s systematic analysis (1976).

Axon fiber diameter is usually correlated with conductance velocity of action potentials, so these axons may mediate fast neuronal signals. To encode temporal discretization of acoustic signals, we may expect neuronal signals to be fast relative to olfactory signals. Our discovery of putative gap junctions between JO fibers may suggest a mechanism for synchronization of action potentials along the parallel fibers. This would also help to maintain highly discretized acoustic information as it flows to the AMC. The significance of this may be further speculated upon by considering that the IPI in Drosophila is very short, about 35 msec, which is equivalent to a pulse rate of 28 Hz (Wheeler et al., 1988; Tauber and Eberl, 2001). However, the antennal nerve encodes not only IPI, but the carrier frequency of the pulse, which can be 150–350 Hz (Wheeler et al., 1988). In addition, responses to sinusoidal stimuli up to 1 kHz can be encoded in the antennal nerve. Furthermore, it encodes this carrier frequency primarily at the second harmonic (i.e., twice the carrier frequency) (Eberl et al., 2000). Thus, temporal resolution is on the order of < 1 msec between spikes. At this high rate, some temporal variability or asynchrony between neurons in reporting the mechanoresponse to the originally synchronous stimulus to the axon terminals is likely to arise. Electrical coupling may not be adequate to spread an action potential from a firing axon to a nonfiring neighbor. However, it may be sufficient to advance or delay an also firing neighbor, much like a slight hyper- or depolarization could delay or advance an action potential (Fayyazuddin and Dickinson, 1996; Frye and Dickinson, 2004). The resulting synchronization could then ensure maximal summation at the axon terminals in the AMC, with sharp temporal distinction.

Acetylcholine is a primary excitatory neurotransmitter in insect CNS (Breer and Sattelle, 1987; Lee and O’Dowd, 1999), as opposed to glutamate as the primary excitatory transmitter in the vertebrate CNS. JO neurons have been described as cholinergic, on the basis of expression of a choline acetyltransferase (ChAT)-lacZ fusion gene (Kitamoto et al., 1995). Expression of ChAT protein, which is the most reliable marker for cholinergic neurons (Salvaterra and Vaughn, 1989), has been shown in the JO neurons of the antenna and in their central projection sites in the AMC (Yasuyama and Salvaterra, 1999). Cholinergic projection boutons in the mushroom body calyx were described as large synaptic boutons, 2–7 μm in diameter, bearing numerous small clear vesicles, and forming divergent contacts to numerous postsynaptic profiles (Yusuyama et al., 2002, 2003). These lines of evidence together support our inference that the small clear synaptic vesicles we describe in JO neuron terminals likely carry acetylcholine as the neurotransmitter.

The presence of both synaptic vesicles and putative gap junctions at the JO synapses indicate that these are mixed synapses, likely to mediate both chemical and electrical synaptic activity. Mixed synapses have been found frequently in insect neural circuits. Gap junctions, in addition to serving as electrical synapses, may also serve a role in the initial establishment of the synapse during development. Some developing synapses have been shown to require temporary gap junctions to establish chemical synapses (Lopresti et al., 1974; Kandler and Katz, 1998; Curtin et al., 2002), perhaps as a way to provide electrical connectivity to synchronize pre- and postsynaptic activity. In insect giant fiber escape circuits, electrical components predominate (Thomas and Wyman, 1984; Phelan et al., 1996, 1998; Sun and Wyman, 1996). Other circuits, such as the feedback from the haltere afferents to a wing motor neuron, display mixed chemical and electrical synapses (Fayyazuddin and Dickinson, 1996; Trimarchi and Murphey, 1997).

We are very interested in identifying the postsynaptic neurons in the AMC. Others have described descending neurons in the large Dipteran, Sarcophaga, that respond to antennal mechanosensory inputs resembling air currents during flight (Gronenberg and Strausfeld, 1990). These descending neurons also respond to moving visual stimuli, and are likely to integrate the motion cues from these two sensory modalities. Whether these neurons would respond to the types of vibratory stimuli experienced by the Drosophila antenna during courtship is unknown.

In conclusion, we have shown that the X-gal labeling technique at the EM level, combined with the genetic tools for Drosophila research, is a powerful tool to begin to describe and dissect neural circuits in the CNS. Our results indicate that there are anatomical features of the parallel JO fibers that could mediate synchronization of auditory signals along the antennal nerve. The JO neurons terminate in the AMC with putative mixed synapses that have extensive, divergent-type associations with numerous small postsynaptic structures. This study serves as the basis for ultrastructural examination of auditory behavior mutants in the AMC and as the beginning of a dissection of the auditory neural circuit in Drosophila.

Footnotes

Grant sponsor: Whitehall Foundation; Grant sponsor: National Institutes of Health; Grant number: DC04848 (to D.F.E.).

LITERATURE CITED

- Bennet-Clark HC, Ewing AW. Pulse interval as a critical parameter in the courtship song of Drosophila melanogaster. Anim Behav. 1969;17:755–759. [Google Scholar]

- Blagburn JM, Alexopoulos H, Davies JA, Bacon JP. Null mutation in shaking-B eliminates electrical, but not chemical, synapses in the Drosophila giant fiber system: a structural study. J Comp Neurol. 1999;404:449–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boekhoff-Falk G. Hearing in Drosophila: development of Johnston’s organ and emerging parallels to vertebrate ear development. Dev Dyn. 2005;232:550–558. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyan GS. Development of the insect auditory system. In: Hoy RR, Popper AN, Fay RR, editors. Comparative hearing: insects. New York: Springer; 1998. pp. 97–138. [Google Scholar]

- Breer H, Sattelle DB. Molecular properties and functions of insect acetylcholine receptors. J Insect Physiol. 1987;33:771–790. [Google Scholar]

- Brownell WE, Bader CR, Bertrand D, de Ribaupierre Y. Evoked mechanical responses of isolated cochlear outer hair cells. Science. 1985;227:194–196. doi: 10.1126/science.3966153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell JC, Eberl DF. Towards a molecular understanding of Drosophila hearing. J Neurobiol. 2002;53:172–189. doi: 10.1002/neu.10126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe Y, Magnasco MO, Hudspeth AJ. A model for amplification of hair-bundle motion by cyclical binding of Ca2+to mechanoelectrical-transduction channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:15321–15326. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coro F, Kössl M. Distortion-product otoacoustic emissions from the tympanic organ in two noctuid moths. J Comp Physiol A. 1998;183:525–531. [Google Scholar]

- Curtin KD, Zhang Z, Wyman RJ. Gap junction proteins are not interchangeable in development of neural function in the Drosophila visual system. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:3379–3388. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.17.3379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberl DF. Feeling the vibes: chordotonal mechanisms in insect hearing. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1999;9:389–393. doi: 10.1016/S0959-4388(99)80058-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberl DF, Duyk GM, Perrimon N. A genetic screen for mutations that disrupt an auditory response in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:14837–14842. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberl DF, Hardy RW, Kernan M. Genetically similar transduction mechanisms for touch and hearing in Drosophila. J Neurosci. 2000;20:5981–5988. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-16-05981.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fayyazuddin A, Dickinson MH. Haltere afferents provide direct, electrotonic input to a steering motor neuron in the blowfly, Calliphora. J Neurosci. 1996;16:5225–5232. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-16-05225.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritzsch B, Beisel KW, Bermingham NA. Developmental evolutionary biology of the vertebrate ear: conserving mechanoelectric transduction and developmental pathways in diverging morphologies. Neuro-Report. 2000;11:R35–R44. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200011270-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye MA, Dickinson MH. Closing the loop between neurobiology and flight behavior in Drosophila. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2004;14:729–736. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Göpfert MC, Robert D. Active auditory mechanics in mosquitoes. Proc R Soc Lond B. 2001a;268:333–339. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2000.1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Göpfert MC, Robert D. Turning the key on Drosophila audition. Nature. 2001b;411:908. doi: 10.1038/35082144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Göpfert MC, Robert D. The mechanical basis of Drosophila audition. J Exp Biol. 2002;205:1199–1208. doi: 10.1242/jeb.205.9.1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Göpfert MC, Robert D. Motion generation by Drosophila mechanosensory neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:5514–5519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0737564100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Göpfert MC, Humphris ADL, Albert JT, Robert D, Hendrich O. Power gain exhibited by motile mechanosensory neurons in Drosophila ears. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:325–330. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405741102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gronenberg W, Strausfeld NJ. Descending neurons supplying the neck and flight motor of Diptera: physiological and anatomical characteristics. J Comp Neurol. 1990;302:973–991. doi: 10.1002/cne.903020420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JC. The mating of a fly. Science. 1994;264:1702–1714. doi: 10.1126/science.8209251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedwig B, Poulet JFA. Complex auditory behaviour emerges from simple reactive steering. Nature. 2004;430:781–785. doi: 10.1038/nature02787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennig RM, Franz A, Stumpner A. Processing of auditory information in insects. Microsc Res Tech. 2004;63:351–374. doi: 10.1002/jemt.20052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoy RR. Acute as a bug’s ear: an informal discussion of hearing in insects. In: Hoy RR, Popper AN, Fay RR, editors. Comparative hearing: insects. New York: Springer; 1998. pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Jarman AP. Studies of mechanosensation using the fly. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:1215–1218. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.10.1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandler K, Katz LC. Coordination of neuronal activity in developing visual cortex by gap junction-mediated biochemical communication. J Neurosci. 1998;18:1419–1427. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-04-01419.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamoto T, Ikeda K, Salvaterra PM. Regulation of choline acetyltransferase/lacZ fusion gene expression in putative cholinergic neurons of Drosophila melanogaster. J Neurobiol. 1995;28:70–81. doi: 10.1002/neu.480280107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kössl M, Boyan GS. Acoustic distortion products from the ear of a grasshopper. J Acoust Soc Am. 1998a;104:326–335. [Google Scholar]

- Kössl M, Boyan GS. Otoacoustic emissions from a nonvertebrate ear. Naturwiss. 1998b;85:124–127. doi: 10.1007/s001140050467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyriacou CP, Hall JC. Interspecific genetic control of courtship song production and reception in Drosophila. Science. 1986;232:494–497. doi: 10.1126/science.3083506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyriacou CP, Hall JC. Genetic and molecular analysis of Drosophila behavior. Adv Genet. 1994;31:139–186. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2660(08)60397-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D, O’Dowd DK. Fast excitatory synaptic transmission mediated by nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in Drosophila neurons. J Neurosci. 1999;19:5311–5321. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-13-05311.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lienhard MC, Stocker RF. The development of the sensory neuron pattern in the antennal disc of wild-type and mutant (lz3, ssa) Drosophila melanogaster. Development. 1991;112:1063–1075. doi: 10.1242/dev.112.4.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopresti V, Macagno ER, Levinthal C. Structure and development of neuronal connections in isogenic organisms: transient gap junctions between growing optic axons and lamina neuroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1974;71:1098–1102. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.4.1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manley GA, Gallo L. Otoacoustic emissions, hair cells, and myosin motors. J Acoust Soc Am. 1997;102:10997–11002. doi: 10.1121/1.419858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier T, Reichert H. Embryonic development and evolutionary origin of the orthopteran auditory system. J Neurobiol. 1990;21:592–610. doi: 10.1002/neu.480210407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinertzhagen IA. Ultrastructure and quantification of synapses in the insect nervous system. J Neurosci Methods. 1996;69:59–73. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0270(96)00021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield KP. Tonotopic organisation of auditory receptors in Tettigoniidae (Orthoptera: Ensifera) J Comp Physiol A. 1982;147:461–469. [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield BP, Kleindienst HU, Huber F. Physiology and tonotopic organization of auditory receptors in the cricket Gryllus bimaculatus DeGeer. J Comp Physiol A. 1986;159:457–464. doi: 10.1007/BF00604165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan P, Nakagawa M, Wilkin MB, Moffat KG, O’Kane CJ, Davies JA, Bacon JP. Mutations in shaking-B prevent electrical synapse formation in the Drosophila giant fiber system. J Neurosci. 1996;16:1101–1113. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-03-01101.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan P, Stebbings LA, Baines RA, Bacon JP, Davies JA, Ford C. Drosophila Shaking-B protein forms gap junctions in paired Xenopus oocytes. Nature. 1998;391:181–184. doi: 10.1038/34426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollack GS. Neural processing of acoustic signals. In: Hoy RR, Popper AN, Fay RR, editors. Comparative hearing: insects. New York: Springer; 1998. pp. 139–196. [Google Scholar]

- Pollack G. Who, what, where? Recognition and localization of acoustic signals by insects. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2000;10:763–767. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00161-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollack GS, Imaizumi K. Neural analysis of sound frequency in insects. BioEssays. 1999;21:295–303. [Google Scholar]

- Power ME. The antennal centers and their connections within the brain of Drosophila melanogaster. J Comp Neurol. 1946;85:485–517. doi: 10.1002/cne.900850307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prier KR, Boyan GS. Synaptic input from serial chordotonal organs onto segmentally homologous interneurons in the grasshopper Schistocerca gregaria. J Insect Physiol. 2000;46:297–312. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1910(99)00183-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie MG, Halsey EJ, Gleason JM. Drosophila song as a species-specific mating signal and the behavioural importance of Kyriacou & Hall cycles in D. melanogaster. Anim Behav. 1999;58:649–657. doi: 10.1006/anbe.1999.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert D, Göpfert MC. Novel schemes for hearing and orientation in insects. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2002;12:715–720. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(02)00378-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert D, Miles RN, Hoy RR. Directional hearing by mechanical coupling in the parasitoid fly Ormia ochracea. J Comp Physiol A. 1996;179:29–44. doi: 10.1007/BF00193432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert D, Miles RN, Hoy RR. Tympanal mechanics in the parasitoid fly Ormia ochracea: intertympanal coupling during mechanical vibration. J Comp Physiol A. 1998;183:443–452. [Google Scholar]

- Salvaterra PM, Vaughn JE. Regulation of choline acetyltransferase. Int Rev Neurobiol. 1989;31:81–143. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7742(08)60278-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanbhag SR, Singh K, Singh RN. Ultrastructure of the femoral chordotonal organs and their novel synaptic organization in the legs of Drosophila melanogaster Meigen (Diptera: Drosophilidae) Int J Insect Morphol Embryol. 1992;21:311–322. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma Y, Cheung U, Larsen EW, Eberl DF. pPTGAL, a convenient Gal4 P-element vector for testing expression of enhancer fragments in Drosophila. Genesis. 2002;34:115–118. doi: 10.1002/gene.10127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimohigashi M, Meinertzhagen IA. The shaking B gene in Drosophila regulates the number of gap junctions between photoreceptor terminals in the lamina. J Neurobiol. 1998;35:105–117. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(199804)35:1<105::aid-neu9>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D, Wohlgemuth J, Calvi BR, Franklin I, Gelbart WM. hobo enhancer trapping mutagenesis in Drosophila reveals an insertion specificity different from P elements. Genetics. 1993;135:1063–1076. doi: 10.1093/genetics/135.4.1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocker RF. Fine structural comparison of the antennal nerve in the homeotic mutant Antennapedia with the wild-type antennal and second leg nerves of Drosophila melanogaster. J Morphol. 1979;160:209–222. doi: 10.1002/jmor.1051600207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocker RH. The organization of the chemosensory system in Drosophila melanogaster: a review. Cell Tissue Res. 1994;275:3–26. doi: 10.1007/BF00305372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocker RF, Lawrence PA. Sensory projections from normal and homoeotically transformed antennae in Drosophila. Dev Biol. 1981;82:224–237. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(81)90448-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocker RF, Edwards JS, Palka J, Schubiger G. Projection of sensory neurons from a homeotic mutant appendage, Antennapedia, in Drosophila melanogaster. Dev Biol. 1976;52:210–220. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(76)90241-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stölting H, Stumpner A. Tonotopic organization of auditory receptors of the bushcricket Pholidoptera griseoaptera (Tettigoniidae, Decticinae) Cell Tissue Res. 1998;294:377–386. doi: 10.1007/s004410051187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strausfeld NJ. Atlas of an insect brain. New York: Springer; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Stumpner A. A species-specific frequency filter through specific inhibition, not specific excitation. J Comp Physiol A. 2002;188:239–248. doi: 10.1007/s00359-002-0299-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stumpner A, von Helversen D. Evolution and function of auditory systems in insects. Naturwiss. 2001;88:159–170. doi: 10.1007/s001140100223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y-A, Wyman RJ. Passover eliminates gap junctional communication between neurons of the giant fiber system in Drosophila. J Neurobiol. 1996;30:340–348. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4695(199607)30:3<340::AID-NEU3>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tauber E. Bidirectional communication system in katydids: the effect on chorus structure. Behav Ecol. 2001;12:308–312. [Google Scholar]

- Tauber E, Eberl DF. Song production in auditory mutants of Drosophila: the role of sensory feedback. J Comp Physiol A. 2001;187:341–348. doi: 10.1007/s003590100206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tauber E, Pener MP. Song recognition in female bushcrickets Phaneroptera nana. J Exp Biol. 2000;203:597–603. doi: 10.1242/jeb.203.3.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JB, Wyman RJ. Mutations altering synaptic connectivity between identified neurons in Drosophila. J Neurosci. 1984;4:530–538. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.04-02-00530.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todi SV, Sharma Y, Eberl DF. Anatomical and molecular design of the Drosophila antenna as a flagellar auditory organ. Microsc Res Tech. 2004;63:388–399. doi: 10.1002/jemt.20053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trimarchi JR, Murphey RK. The shaking-B2 mutation disrupts electrical synapses in a flight circuit in adult Drosophila. J Neurosci. 1997;17:4700–4710. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-12-04700.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tunstall DN, Pollack GS. Temporal and directional processing by an identified interneuron, ON1, compared in cricket species that sing with different tempos. J Comp Physiol A. 2005;191:363–372. doi: 10.1007/s00359-004-0591-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uga S, Kuwabara M. On the fine structure of the chordotonal sensillum in antenna of Drosophila melanogaster. J Electron Microsc. 1965;14:173–181. [Google Scholar]

- van Staaden MJ, Römer H. Evolutionary transition from stretch to hearing organs in ancient grasshoppers. Nature. 1998;394:773–776. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler DA, Fields WL, Hall JC. Spectral analysis of Drosophila courtship songs: D. melanogaster, D. simulans, and their interspecific hybrid. Behav Genet. 1988;18:675–703. doi: 10.1007/BF01066850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yack JE. The structure and function of auditory chordotonal organs in insects. Microsc Res Tech. 2004;63:315–337. doi: 10.1002/jemt.20051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yack JE, Fullard JH. The mechanoreceptive origin of insect tympanal organs: a comparative study of similar nerves in tympanate and atympanate moths. J Comp Neurol. 1990;300:523–534. doi: 10.1002/cne.903000407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuyama K, Salvaterra PM. Localization of choline acetyltransferase-expressing neurons in Drosophila nervous system. Microsc Res Tech. 1999;45:65–79. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19990415)45:2<65::AID-JEMT2>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yusuyama K, Meinertzhagen IA, Schürmann F-W. Synaptic organization of the mushroom body calyx in Drosophila melanogaster. J Comp Neurol. 2002;445:211–226. doi: 10.1002/cne.10155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yusuyama K, Meinertzhagen IA, Schürmann F-W. Synaptic connections of cholinergic antennal lobe relay neurons innervating the lateral horn neuropil in the brain of Drosophila melanogaster. J Comp Neurol. 2003;466:299–315. doi: 10.1002/cne.10867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]