Abstract

Huntingtin, the protein product of the Huntington's disease (HD) gene is known to interact with the tumor suppressor p53. It has recently been shown that activation of p53 upregulates the level of huntingtin, both in vitro and in vivo, while p53 deficiency in HD-transgenic flies and mice has been found to be beneficial. To explore further the involvement of p53 in HD pathogenesis, we generated mice homozygous for a mutant allele of Hdh (HdhQ140) and with zero, one, or two functional alleles of p53. p53 deficiency resulted in a reduction of mutant huntingtin expression in brain and testis, an increase in proenkephalin mRNA expression, and a significant increase in nuclear aggregate formation in the striatum. Because aggregation of mutant huntingtin is suggested to be a protective mechanism, both the increase in aggregate load and the restoration of proenkephalin expression suggest a functional rescue of HD phenotypes by p53 deficiency.

Keywords: aging, mouse model, polyglutamine, neurodegeneration, proenkephalin, transcription

INTRODUCTION

The sequence-specific transcription factor, p53, is a stress-induced regulator of cell function that has differing activities depending on p53 protein level, the inducing agent, and the cell type. p53 is also involved in lifespan regulation (Tyner et al., 2002; Maier et al., 2004), cell cycle control (Levine, 1997), DNA repair, and apoptosis (Vogelstein et al., 2000; Gomez-Lazaro et al., 2004). Because p53 is involved in cell death, it has the potential for playing a key role in the progression of degenerative diseases, and its role has been studied in some known disorders. In the neurodegenerative disorder Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA), the nor mal interaction between SMN protein and p53 is reduced in the presence of SMN1 gene mutations, and this results in enhanced disease severity (Young et al., 2002). Deletion of p53 in a mouse model of the polyglutamine repeat disorder spinocerebellar ataxia 1 (SCA1) has been found to rescue Purkinje cell pathology and slow disease progression (Shahbazian et al., 2001). Most recently, p53 has been found to affect the phenotype of experimental models of the neurodegenerative disorder, Huntington's disease (HD) (Bae et al., 2005). The connection between p53 and HD is particularly striking in light of the fact that mice nullizygous for p53 display variable expressivity of brain lesions very similar to those identified in Hdh-nullizygous mouse brain. Neurodegeneration of the basal ganglia comparable to that seen in Hdh−/− brain (Dragatsis et al., 2000) has been observed in approximately 25% of p53−/− mice (Amson et al., 2000).

HD is a progressive, autosomal dominant neurological disease that results from expansion of a polyglutamine (CAG) stretch located within the huntingtin protein (htt) encoded by the HD gene. Although htt exhibits widespread distribution in both the brain and peripheral tissues, the GABAergic medium spiny neurons of the striatum and the large pyramidal neurons in layers III, V, and VI of the cerebral cortex undergo preferential degeneration (Sharp et al., 1995; Ho et al., 2001; Sieradzan and Mann, 2001). The abundance of huntingtin protein does not appear to confer vulnerability on striatal neurons, but rather, the expression of mutant htt in corticostriatal neurons seems to render them destructive to the striatal neurons that they innervate (Fusco et al., 1999). Both prior and subsequent to neuronal death, the indirect pathway of basal ganglia output is affected most severely, resulting in an increase in involuntary movements associated with loss of proenkephalin expression. On a molecular level, intraneuronal inclusions that contain an amino-terminal fragment of mutant htt have been identified in the brains of both human HD patients and HD animal models (DiFiglia et al., 1997; Ho et al., 2001). Inclusion formation does not directly correlate with increased neuronal vulnerability, as striatal neurons have been shown to form fewer inclusions than cortical neurons (Meade et al., 2002). However, within the striatum, vulnerable neuronal subtypes do form more inclusions than unaffected neuronal subtypes, and they do so at an earlier age (Meade et al., 2002). The consequences of inclusion formation have been unclear, with earlier reports suggesting a pathological function of inclusions in HD progression (Hackam et al., 1999). However, other groups have found that aggregate inhibition is detrimental to the cell (Saudou et al., 1998) and that formation of aggregates can actually predict improved survival and lead to decreased levels of mutant htt elsewhere in neurons (Arrasate et al., 2004). Furthermore, the “shortstop” mouse model of HD, which expresses an N-terminal huntingtin fragment containing ∼120 CAG repeats, develops widespread inclusions, but displays no evidence of neuronal dysfunction or degeneration (Slow et al., 2005). Most recently, a compound was identified that increases inclusion formation in cellular models of HD, and concomitantly prevents huntingtin-mediated proteasome dysfunction (Bodner et al., 2006).

As described above, the involvement of p53 in the pathology of neurodegenerative diseases, including HD, has been established, and a deficiency in p53 can result in neurological deficits and apoptotic brain lesions similar to those identified in Hdh-nullizygous mouse brain (Amson et al., 2000; Dragatsis et al., 2000). Together, this suggested to us that p53 and Hdh might interact functionally, and that the modification of p53 status on an HD background might result in a change of HD phenotype. This hypothesis is supported by recent work in which the activation of p53 in cultured cells was found to induce huntingtin transcription, and γ-irradiation of mice was found to upregulate the level of wildtype htt protein in a p53-dependent manner (Feng et al., 2006). Therefore, we examined the genetic interaction between p53 and Hdh using tissues and mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) derived from a knock-in mouse model of HD expressing 140 glutamine repeats (Menalled et al., 2003) and with zero, one, or two functional copies of p53.

MATERIALS & METHODS

Animals

All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines described in Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals by the National Research Council and reviewed and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Virginia. The HdhQ140/Q140 mice were generated using homologous recombination in ES cells by Dr. Scott Zeitlin, and have been described previously (Menalled et al., 2003). Mice containing a floxed Hdh allele in the endogenous Hdh locus were generated using homologous recombination in ES cells by Dr. Scott Zeitlin, and have been described previously (Dragatsis et al., 2000). p53−/− mice (C57 Bl/6) were obtained from Taconic Laboratories (Hudson, NY).

Generation of huntingtin reporter constructs

A mouse Hdh promoter fragment was obtained by digesting a targeting vector containing a 5′ genomic piece (4.5kb) of mouse Hdh sequence (previously described in (Zeitlin et al., 1995) with HindIII and AlwNI to yield a ∼1500bp fragment. The ends of the 1500-bp promoter fragment were filled in with Klenow, and then cloned into the SmaI site of the pGL3-Basic vector (Promega, Madison, WI), yielding pHdhluc. Orientation was verified by analytical restriction enzyme digest. The generation of the human pHDluc reporter construct has been described previously (Ryan and Scrable, 2004).

Assay of huntingtin promoter activity

p53+/+ and p53−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were prepared as described previously (Maier et al., 2004). MEFs were transiently transfected using Lipofectamine reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with the pHDluc or pHdhluc reporter construct, varying doses of p53 expression vector, and the pRL-TK vector (Promega, Madison, WI) to correct for transfection efficiency. Twenty-four hours following transfection, cells were treated with Dulbecco minimal essential medium (DMEM) (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 1% fetal calf serum for 24 hours, after which cells were lysed and assayed for luciferase activity using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System protocol (Promega, Madison, WI).

Analysis of huntingtin protein in transfected MEFs and in brain and peripheral tissues

p53+/+ and p53−/− MEFs were transiently transfected using Lipofectamine reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with varying doses of p53 expression vector. Twenty-four hours following transfection, cells were treated with DMEM (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 1% fetal calf serum for 24 hours, after which cells were serum deprived for 3 hours in the presence of 0.5μM adriamycin, 0.5μM Trichostatin A, and 5mM nicotinamide. Protein extracts were prepared with RIPA lysis buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors (Complete Mini protease inhibitor cocktail tablets, Roche, Indianapolis, IN). HdhQ140/Q140, HdhQ140/+, and Hdh+/+ animals were generated having zero, one or two p53 alleles. Tissues were dissected, and protein extracts were prepared with RIPA lysis buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). Western blots were generated using standard procedures. Monoclonal anti-huntingtin antibody 2166 (Chemicon, Temecula, CA) was used at a 1:1000 dilution to detect total huntingtin protein. Antigen-antibody complexes were further reacted with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (Jackson Immuno-Research Laboratories, West Grove, PA) and detected by chemiluminescence (SuperSignal Pico reagent, Pierce, Rockford, IL). The blots were stripped and re-reacted with monoclonal anti-GAPDH antibody (1:5000 dilution, Ambion, Austin, TX) or monoclonal anti-actin antibody (1:10000 dilution, MP Biomedicals Inc., Solon, OH) to normalize the signals. Signals were quantified by laser densitometry on a Molecular Dynamics (Sunnyvale, CA) instrument running ImageQuant software (GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA).

Immunohistochemistry

Whole brains were fresh frozen in methylbutane pre-chilled on dry ice, and mounted in OCT for cryosectioning. Brains were sectioned into 25μm slices, fixed for 15 minutes in 4% paraformaldehyde, washed three times in PBS containing 0.05% TritonX-100 (PBST), and blocked in PBST containing 10% heat-inactivated donkey serum for 30 minutes at room temperature. Monoclonal anti-huntingtin antibody mEM48 (#MAB5374, Chemicon, Temecula, CA) was used at a 1:100 dilution to detect aggregated huntingtin protein. Primary antibody was diluted in blocking solution, and sections were incubated overnight at 4°C. Sections were washed 3 times in PBST containing 1% heat-inactivated donkey serum, and incubated with donkey anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 568 secondary antibody (diluted 1:300, Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA) for 1 hour at room temperature. After 3 washes in PBST, sections were counterstained with DAPI, treated with Autofluorescence Eliminator Reagent per manufacturer's protocol (#2160, Chemicon, Temecula, CA), and mounted. Sections were visualized using a Zeiss Axiophot fluorescence microscope. Fluorescence images were captured using a Sony DSC-S7 digital camera and processed using Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems Inc., San Jose, CA).

Northern Blot Analysis

Brain tissue was harvested from animals of the desired genotypes, and whole-brain RNA extracted using Tri-Reagent (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, OH). Northern blotting and hybridizations were performed as described previously (Cronin et al., 2001).

RESULTS

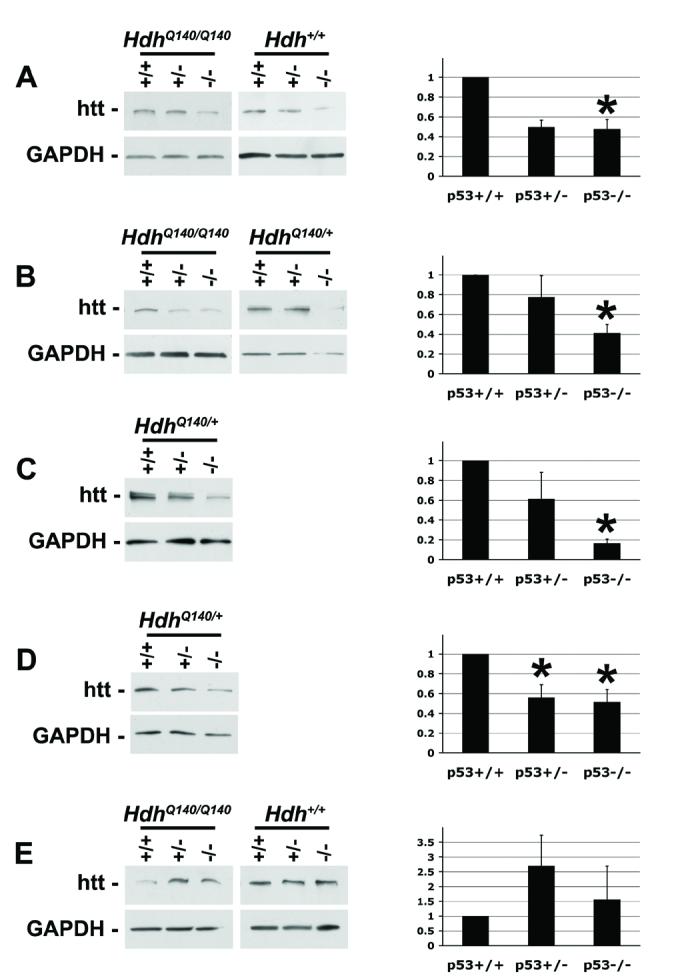

The level of huntingtin protein is lower in mice deficient in p53

The phenocopy of Hdh−/− brain lesions in a significant fraction of p53−/− mice suggested to us that p53 and htt might lie in a shared pathway that protects neuronal lifespan, and that loss of one or the other could lead to neurodegeneration. The fact that neurodegeneration is 100% penetrant in Hdh−/− mice but only ∼25% penetrant in p53−/− mice, furthermore, suggested that p53 lies upstream of htt in this pathway. According to this model, when loss of p53 results in loss of htt, neurodegeneration occurs. To determine if p53 controls the level of htt, we compared htt levels in mice with nor mal or expanded (Q140) alleles of Hdh having zero, one, or two functional p53 alleles. Testis, liver, and total brain tissues were harvested, and the cortex and the core region of the striatum were dissected from the total brain. The level of htt protein in each sample was determined using Western blot analysis. As shown in Fig.1, increasing the dose of p53 in vivo leads to a pronounced increase in the level of both mutant and wildtype htt protein in the total brain (Fig.1A), as well as in isolated cortex (Fig.1B) and striatum (Fig.1C), and the testis (Fig.1D). Testis and brain are reported to have the highest level of htt expression (Sharp et al., 1995), and the brain is the most affected tissue in HD. In liver, an unaffected tissue where htt expression is lower, this trend was not apparent (Fig.1E).

Fig.1.

The level of huntingtin protein is lower in mice deficient in p53

Western blot of htt protein in total brain (A), striatum (B), cortex (C), testis (D), and liver (E) dissected from animals ranging from 2 to 7 months of age. Blots were stripped and reprobed with anti-GAPDH or anti-actin antibody, and densitometry was performed. One representative western blot for each tissue is shown. Densitometry values derived from at least three independent experiments were averaged, and the results are graphed in the histograms in the right column. As the same dose-responsive trend was apparent in HdhQ140/Q140, HdhQ140/+, and Hdh+/+ animals, densitometry values were pooled within each p53 genotype; for example HdhQ140/Q140p53−/−, HdhQ140/+p53−/−, and Hdh+/+p53−/− were pooled under the p53−/− category in the histograms.

Error bars = SEM. * statistically different from p53+/+ at p<0.05

The absence of p53 cannot rescue Hdh−/− embryonic lethality

If p53 is an upstream regulator of htt, then loss of p53 should have no effect on the phenotype of mice deficient in Hdh. Mice deficient in Hdh display embryonic lethality (Duyao et al., 1995; Nasir et al., 1995; Zeitlin et al., 1995), and this trait is fully penetrant. To verify that loss of p53 could not rescue embryonic lethality of Hdh−/− embryos, we intercrossed animals heterozygous for Hdh and nullizygous for p53 and genotyped the progeny. Of the 29 progeny born to these crosses, 12 were Hdh+/+p53−/−, 17 were Hdh+/-p53−/−, and zero were Hdh−/−p53−/−.

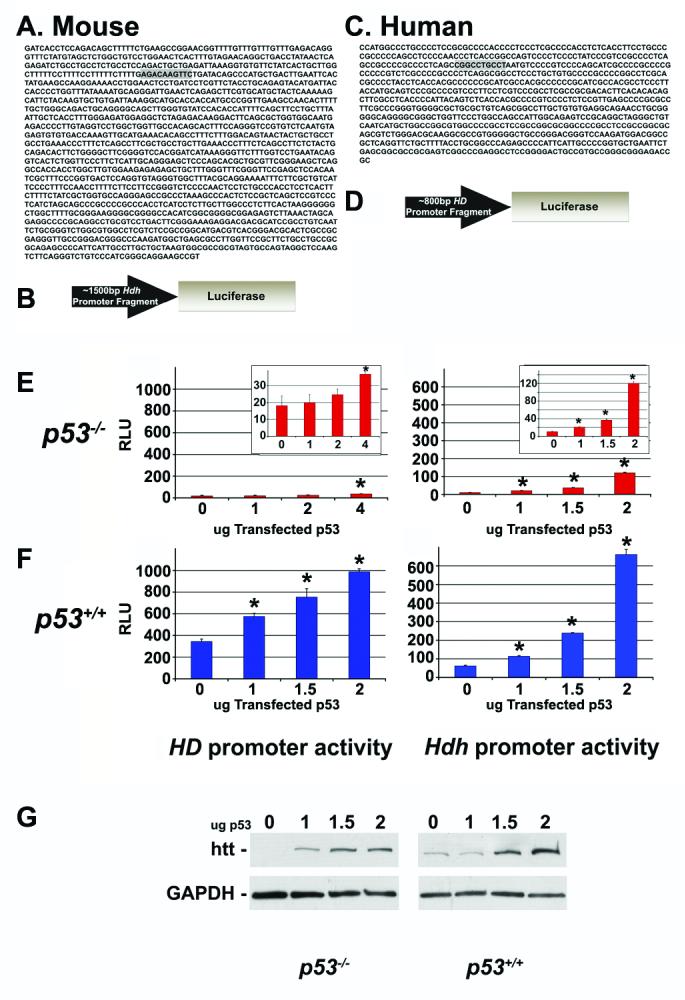

The murine and human huntingtin promoters contain putative p53 consensus sequences

Because p53 is a sequence-specific transcription factor, one mechanism by which p53 could modify htt protein level is by transactivating the huntingtin promoter. To identify potential p53 response elements in the huntingtin promoter, we analyzed the proximal 1500bp region of the murine Hdh promoter region using Promolign (Zhao et al., 2004). A half consensus sequence corresponding to the p53 response element was identified ∼1285bp upstream from translation start (Fig.2A; consensus sequence shaded in grey). Likewise, we analyzed the proximal 800bp region of the human HDpromoter region using Promolign, and a half consensus sequence corresponding to the p53 response element was identified ∼630bp upstream of translation start (Fig.2C; consensus sequence shaded in grey). We also found an additional half-consensus sequence ∼1200bp upstream of translation start (not shown).

Fig.2.

- Mouse Hdh proximal promoter region A half consensus sequence corresponding to the p53 response element (shaded in gray) is located ∼1285bp upstream from translation start.

- Hdhluc reporter gene A ∼1500bp fragment of murine Hdh promoter was cloned in front of the luciferase gene to generate a Hdh reporter gene. This promoter fragment contains the single half-response element for p53 highlighted in Fig.2A above.

- Human HD proximal promoter region A half consensus sequence corresponding to the p53 response element (shaded in gray) is located ∼630bp upstream of translation start.

- HDluc reporter gene An ∼800bp fragment of the human HD promoter was cloned in front of the luciferase gene to generate a HD reporter gene. This promoter fragment contains the single half-response element for p53 highlighted in Fig.2C above.

- The HDluc or Hdhluc reporter construct (left and right panel, respectively) was co-transfected into p53−/− MEFs with increasing doses of p53 expression vector. Promoter activation in response to varying doses of p53 was determined by assaying luciferase activity. Individual groups were analyzed by two-tailed Student's t-test. RLU = Relative Light Units; Error bars = SEM; * statistically different from 0ug at p<0.005

- The HDluc or Hdhluc reporter construct (left and right panel, respectively) was co-transfected into p53+/+ MEFs with increasing doses of p53 expression vector. Promoter activation in response to varying doses of p53 was determined by assaying luciferase activity. Individual groups were analyzed by two-tailed Student's t-test. RLU = Relative Light Units; Error bars = SEM; * statistically different from 0ug at p<0.005

- p53+/+ MEFs (left panel) and p53−/− MEFs (right panel) were transfected with 0, 1.0, 1.5, or 2.0ug of p53, and the level of huntingtin protein was determined using western blot analysis. Blots were stripped and reprobed with anti-GAPDH antibody.

p53 modulates HD promoter activity

To determine if the murine and human htt promoters are transactivated by p53, we generated reporter constructs in which luciferase is driven by the ∼1500bp Hdh promoter (Hdhluc; depicted in Fig.2B) or the ∼800bp HD promoter (HDluc; depicted in Fig.2D). These promoter fragments were chosen due to the availability of restriction enzyme sites, and because they contained the p53-consensus sequences that were of interest (shaded in gray in Fig.2A&2C). The HDluc and Hdhluc reporter constructs were co-transfected with increasing doses of p53 expression vector into p53+/+ and p53−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) and htt promoter activation was determined by assaying luciferase activity. As shown in Fig.2, the level of Hdhluc and HDluc activity in p53−/− MEFs is less then that in p53+/+ MEFs. Transfection of additional p53 into p53+/+ MEFs results in an enhancement of Hdhluc and HDluc activity (Fig.2F), while transfection of p53 into p53−/− MEFs increased activity to levels close to that seen in p53+/+MEFs (Fig.2E).

p53 modulates the level of huntingtin protein

To determine if modification of Hdh transactivation by p53 results in an alteration of htt protein level, we transfected p53+/+ and p53−/− MEFs with 0, 1.0, 1.5, or 2.0ug of p53, and determined the level of huntingtin protein using western blot analysis. As shown in Fig.2G, the level of htt protein in p53−/− MEFs is less then that in p53+/+MEFs. Transfection of additional p53 into p53+/+MEFs results in an increase in htt protein level, while transfection of p53 into p53−/− MEFs increases htt protein level to levels close to that seen in p53+/+MEFs.

HdhQ140/Q140p53−/− mice are viable and are born with a normal Mendelian distribution

The fact that p53 had the same effect on mutant and nor mal huntingtin protein levels meant that p53 could affect the phenotype of mice with mutant Hdh alleles in either the positive or the negative direction. In other neurodegenerative diseases, p53 has been shown to be beneficial (such as in SMA) or deleterious (such as in SCA1). To determine how p53 might contribute to HD pathogenesis, we compared the phenotype of mice with two normal Hdh alleles to that of mice in which one or both had been replaced by the mutant allele with an expanded polyglutamine tract containing 140 repeats (HdhQ140). This mouse model of HD recreates the human disease in an accurate and physiologically relevant way (Menalled et al., 2003). If the role of p53 were to promote HD pathogenesis, then deletion of p53 would rescue aspects of the HD phenotype. However, if p53 was protective and delayed the progression of HD pathogenesis, then deletion of p53 would exacerbate the HD phenotype. To distinguish between these possibilities, we performed two different crosses to generate HdhQ140/Q140 animals that were nullizygous for p53. In the first cross, we generated 24 progeny by intercrossing animals heterozygous for mutant Hdh and nullizygous for p53. We predicted that, if they followed a nor mal Mendelian distribution, 6 would be HdhQ140/Q140p53−/−. The actual distribution of progeny was 5 Hdh+/+p53>−/− pups, 14 HdhQ140/+p53−/− pups, and 5 HdhQ140/Q140p53−/− pups. In the second cross, we used p53−/− mice and mated animals heterozygous for mutant Hdh with animals homozygous for mutant Hdh. 49 progeny were born, of which 25 were HdhQ140/+p53−/− pups and 24 were HdhQ140/Q140p53−/− pups.

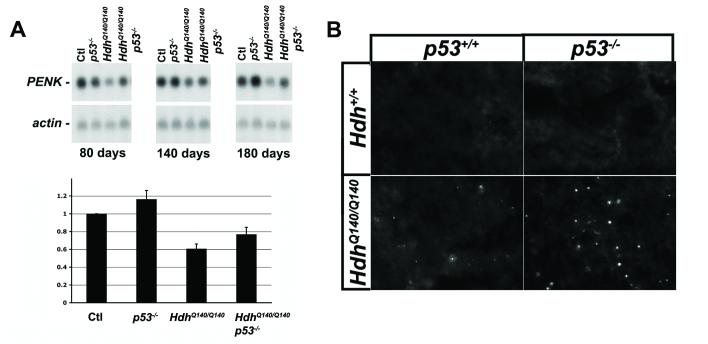

Loss of p53 partially rescues low proenkephalin mRNA levels in Hdh Q140/Q140 mice

If p53 promotes HD pathogenesis, we would predict that animals nullizygous for p53 would present with a less severe HD phenotype. To test this, we examined the levels of the messenger RNA encoding the neurotransmitter proenkephalin. Analysis has shown that proenkephalin mRNA levels are reduced even in early stage HD patients and presymptomatic carriers (Albin et al., 1991), and this reduction is also seen in many HD animal models (Albin et al., 1991; Menalled et al., 2000). To determine if altering p53 status would rescue the levels of proenkephalin mRNA in our model of HD, we performed northern blot analysis on brain tissue taken from control, p53−/−, HdhQ140/Q140, and HdhQ140/Q140p53−/− mice. As shown in Fig.3A, while the levels of proenkephalin mRNA in p53−/− brain and in control brain are not significantly different from each other, the level of proenkephalin mRNA in HdhQ140/Q140 brain is significantly lower at all ages examined. Deletion of p53, however, brings the level of proenkephalin mRNA back to levels close to that in control brain. Quantitation of mRNA levels (Fig. 3A histogram) indicates that proenkephalin mRNA levels in mice with mutant Hdh alleles are restored from 60% of control to 80% in the absence of p53. In this mouse model of HD, there has never been any evidence of neuronal loss in the striatum, especially at the age we are investigating (Menalled et al., 2003). In fact, neuronal loss is rarely seen in any of the knock-in mouse models of HD that have been generated (Hickey and Chesselet, 2003; Menalled, 2005). For this reason, the decrease in proenkephalin mRNA seen in the striatum of HdhQ140/Q140 mice is likely due to a decrease in proenkephalin transcription within HD neurons, rather than the death of HD neurons that express enkephalin (Menalled et al., 2000). In situ hybridization studies performed on brain tissue from patients with presymptomatic Huntington’s disease support this idea (Albin et al., 1991).

Fig.3.

- The level of proenkephalin mRNA was determined by northern blot in the total brain of male mice at 80 (left panel), 140 (middle panel), or 180 days (right panel) of age. Blots were stripped and reprobed for actin mRNA, and densitometry was performed. Striatum from at least six animals in each genotype (ranging in age from 80 to 180 days) were analyzed. Graphed in the histogram is the average ratio of proenkephalin to actin for each genotype.

- Whole brains of the indicated genotypes were fresh frozen, sectioned, and immunolabeled for aggregated huntingtin using monoclonal antibody EM48.

Loss of p53 increases aggregate formation HdhQ140/Q140 striatum

Another aspect of the HD phenotype that could be modified by deletion of p53 is the formation of intranuclear htt aggregates. To test this, we examined aggregate formation in the striata of 6-monthold male Hdh+/+p53 +/+, Hdh+/+p53−/−, HdhQ140/Q140p53+/+, and HdhQ140/Q140p53−/− mice. While the striatum from mice with normal Hdh alleles (Hdh+/+p53+/+ and Hdh+/+p53−/−; top two panels of Fig. 3B) did not contain any detectable inclusions, both striata from mice with mutant Hdh alleles contained numerous inclusions. However, there was also a dramatic difference between mice with or without p53. The striatum from the HdhQ140/Q140 mouse with p53 (Fig. 3B, bottom left panel) displayed moderate inclusion formation, while the striatum from the mutant mouse without p53 (Fig.3B, bottom right panel) had substantially more inclusions. Blood vessels are also stained by EM48 in brain sections from all genotypes analyzed. However, this background staining is identical and easily distinguishable on morphological grounds from the specific staining shown in Fig.3A, that is unique to brains from animals with expanded Hdh alleles.

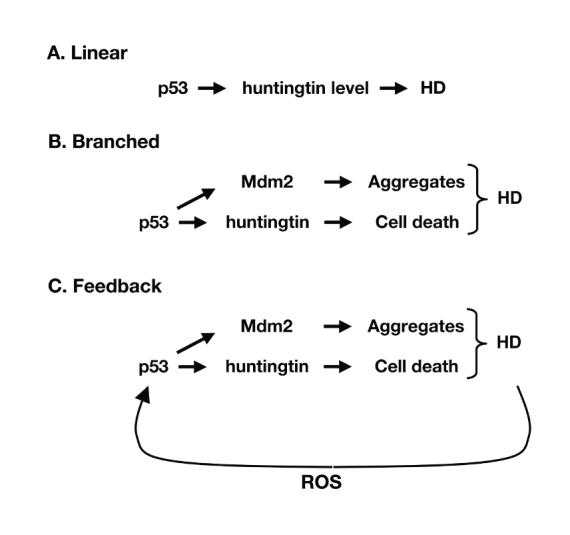

DISCUSSION

The present results indicate that p53 can transactivate the human and murine HD/Hdh promoters, and modify the level of wildtype and mutant htt protein, both in vivo and in vitro. Successive loss of p53 alleles results in a dose-dependent reduction in the level of mutant htt in areas most affected in HD. This reduction in mutant htt is accompanied by a parallel increase in proenkephalin mRNA expression in the brain, and a significant increase in nuclear aggregate formation in the striatum. Because aggregation of mutant htt has been suggested to be a protective mechanism whereby toxic soluble mutant htt is sequestered, both the increase in aggregate load and the restoration of enkephalin expression point to a functional rescue of these HD phenotypes by a deficiency in p53. These results suggest that p53 plays a role in the pathology of Huntington's disease, and that the normal function of p53 may actually promote the disease process. A model for the role of p53 in HD is presented in Fig. 4 and described in more detail below.

Fig.4.

- Linear model of interaction: p53 resides upstream of Hdh and modifies the HD phentoype through the regulation of huntingtin level.

- Branched model of interaction: p53 resides upstream of Hdh and modifies the HD phentoype both through the regulation of huntingtin level, and through the transcriptional regulation of additional genes, such as Mdm2.

- Feedback model of interaction: p53 resides upstream of Hdh, thereby regulating the HD phenotype, and mutant huntingtin modifies p53 activity, possibly through the regulation of p53 level.

The ability of p53 to modify Hdh promoter activity, thereby modulating the level of htt protein, suggests that p53 is upstream of htt, which can be depicted by a simple linear model (Fig.4A). This is supported by the inability of p53 deletion to rescue the lethality caused by complete loss of Hdh. This model of interaction between htt and p53 predicts that deletion of p53 would reduce levels of mutant htt, thereby alleviating the HD phenotype. The partial rescue of proenkephalin mRNA levels in HdhQ140/Q140 brain through the elimination of p53 supports this model of interaction, and suggests that loss of proenkephalin in patients with HD might be a direct effect of the mutant protein.

The normal distribution of p53-deficient progeny carrying mutant Hdh alleles demonstrates that removal of p53 has no deleterious effects on the phenotype of HdhQ140 embryos. Thus, p53 does not appear to play a protective role by suppressing potentially lethal effects of mutant Hdh alleles on viability. However, elimination of p53 does increase the number of EM48-positive aggregates in HdhQ140/Q140 striatum, suggesting that the normal p53 response might inhibit aggregate formation in HD. Because aggregation of mutant htt has been suggested to be a protective mechanism whereby toxic soluble mutant htt is sequestered, this increase in aggregate load would suggest that a deficiency in p53 might rescue the onset of behavioral aspects of HD arising from loss of function in those areas in which aggregate formation is especially prominent. For example, the onset or severity of motor deficits, such as chorea, might be significantly improved. However, it also demonstrates that a simple linear model in which p53 activity is upstream of htt cannot fully explain the p53-Hdh interaction. Instead, the role of p53 in HD pathogenesis must involve at least two pathways, one of which acts directly through htt and affects such things as proenkephalin expression and the other that acts through an as yet unidentified mediator of aggregate formation (Fig. 4B). In this branched model, additional targets of p53 activity are responsible for different aspects of HD phenotype. For example, the transactivation of a p53-target gene by p53 may dictate the degree of aggregate formation found in HD striatum.

To understand how the complex interaction between p53 and htt modulates the HD phenotype it is critical to consider what the disease process itself might do to the activity of p53. p53 is activated as a transcription factor in response to cellular stressors such as DNA damage and oncogenic transformation. Once active, p53 regulates the expression of genes that dictate whether a cell enters senescence, apoptosis, or is repaired and re-enters the cell cycle. Our results demonstrate that p53 can modify the level of htt through transactivation of the htt promoter, and this is supported by work done by Levine's group (Feng et al., 2006). This raises the question of whether htt itself can function as a stress response protein. Previous studies suggest that wildtype htt has an anti-apoptotic function, and that overexpression of htt confers protection against neurodegeneration (Zeitlin et al., 1995; Zhang et al., 2003). If, in fact, htt is upregulated by p53 in response to stress, this would have dire implications in terms of HD pathogenesis. In this paradigm, p53- mediated upregulation of htt promoter activity would lead to an increase in the level of mutant htt protein, which would then exacerbate the disease process. In this way, a normal cellular response to stress—namely, p53-mediated upregulation of the anti-apoptotic activity of wild-type htt—would increase cellular stress and dysfunction.

The ability of p53 to modulate Hdh level may also lead to alterations in the function of p53, itself. We have found that p53 protein levels are upregulated in HdhQ140/Q140 mice and MEFs (data not shown), and this is supported by recent work by Sawa's group (Bae et al., 2005). This suggests that, in addition to the affect of p53 on the level of htt, mutant htt might alter the activity of p53. Therefore, the branched model presented in Fig.4B may also not fully represent the interaction of htt and p53 in HD. Rather, we propose a model of HD pathogenesis in which a downstream effector of HD is capable of feedback on to p53 activity (Fig. 4C). This effector, for example, might be oxidative stress, which has been proposed as an initiating and underlying factor in HD pathogenesis, and is known to activate p53 and initiate p53-mediated apoptotic pathways. If mutant htt can alter the activity of p53, one would predict that cells expressing mutant htt might have numerous changes in their transcriptional profile. In fact, a number of transcriptional alterations have been identified by gene expression profile, RT-PCR, and Northern blot in response to mutant htt (Li et al., 1999; Cha, 2000; Luthi-Carter et al., 2000; Luthi-Carter et al., 2002; Sipione et al., 2002; Kotliarova et al., 2005; Zucker et al., 2005).

Our results suggest that a complex interaction exists between htt and p53, in which p53 modifies htt level, and downstream effectors of mutant htt may feedback on p53. Because p53 is such an integral molecule that is involved in numerous processes, alterations in p53 activity would have drastic repercussions at both the cellular and organismal level. Clearly, more work needs to be done to determine how the function of wildtype htt is affected by p53, and identify the p53-regulated processes that are altered in Huntington's disease pathogenesis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank W. Gluba and B. Bernier for excellent technical support, and E. Clabough for assistance with immunohistochemical procedures. This work was supported by the National Research Service Award predoctoral fellowship NS046197 (A.B.R.) and the Hereditary Disease Foundation (H.S.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Albin RL, Qin Y, Young AB, Penney JB, Chesselet MF. Preproenkephalin messenger RNA-containing neurons in striatum of patients with symptomatic and presymptomatic Huntington's disease: an in situ hybridization study. Ann Neurol. 1991;30:542–549. doi: 10.1002/ana.410300406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amson R, Lassalle JM, Halley H, Prieur S, Lethrosne F, Roperch JP, Israeli D, Gendron MC, Duyckaerts C, Checler F, Dausset J, Cohen D, Oren M, Telerman A. Behavioral alterations associated with apoptosis and down-regulation of presenilin 1 in the brains of p53-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:5346–5350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.10.5346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrasate M, Mitra S, Schweitzer ES, Segal MR, Finkbeiner S. Inclusion body formation reduces levels of mutant huntingtin and the risk of neuronal death. Nature. 2004;431:805–810. doi: 10.1038/nature02998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae BI, Xu H, Igarashi S, Fujimuro M, Agrawal N, Taya Y, Hayward SD, Moran TH, Montell C, Ross CA, Snyder SH, Sawa A. p53 Mediates Cellular Dysfunction and Behavioral Abnormalities in Huntington's Disease. Neuron. 2005;47:29–41. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodner RA, Outeiro TF, Altmann S, Maxwell MM, Cho SH, Hyman BT, McLean PJ, Young AB, Housman DE, Kazantsev AG. From the Cover: Pharmacological promotion of inclusion formation: A therapeutic approach for Huntington's and Parkinson's diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:4246–4251. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511256103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha JH. Transcriptional dysregulation in Huntington's disease. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:387–392. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01609-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronin CA, Gluba W, Scrable H. The lac operator-repressor system is functional in the mouse. Genes Dev. 2001;15:1506–1517. doi: 10.1101/gad.892001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFiglia M, Sapp E, Chase KO, Davies SW, Bates GP, Vonsattel JP, Aronin N. Aggregation of huntingtin in neuronal intranuclear inclusions and dystrophic neurites in brain. Science. 1997;277:1990–1993. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5334.1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragatsis I, Levine MS, Zeitlin S. Inactivation of Hdh in the brain and testis results in progressive neurodegeneration and sterility in mice. Nat Genet. 2000;26:300–306. doi: 10.1038/81593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duyao MP, Auerbach AB, Ryan A, Persichetti F, Barnes GT, McNeil SM, Ge P, Vonsattel JP, Gusella JF, Joyner AL, et al. Inactivation of the mouse Huntington's disease gene homolog Hdh. Science. 1995;269:407–410. doi: 10.1126/science.7618107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Z, Jin S, Zupnick A, Hoh J, de Stanchina E, Lowe S, Prives C, Levine AJ. p53 tumor suppressor protein regulates the levels of huntingtin gene expression. Oncogene. 2006;25:1–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusco FR, Chen Q, Lamoreaux WJ, Figueredo-Cardenas G, Jiao Y, Coffman JA, Surmeier DJ, Honig MG, Carlock LR, Reiner A. Cellular localization of huntingtin in striatal and cortical neurons in rats: lack of correlation with neuronal vulnerability in Huntington's disease. J Neurosci. 1999;19:1189–1202. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-04-01189.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Lazaro M, Fernandez-Gomez FJ, Jordan J. p53: twenty five years understanding the mechanism of genome protection. J Physiol Biochem. 2004;60:287–307. doi: 10.1007/BF03167075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackam AS, Singaraja R, Zhang T, Gan L, Hayden MR. In vitro evidence for both the nucleus and cytoplasm as subcellular sites of pathogenesis in Huntington's disease. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:25–33. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickey MA, Chesselet MF. Apoptosis in Huntington's disease. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2003;27:255–265. doi: 10.1016/S0278-5846(03)00021-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho LW, Carmichael J, Swartz J, Wyttenbach A, Rankin J, Rubinsztein DC. The molecular biology of Huntington's disease. Psychol Med. 2001;31:3–14. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799002871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotliarova S, Jana NR, Sakamoto N, Kurosawa M, Miyazaki H, Nekooki M, Doi H, Machida Y, Wong HK, Suzuki T, Uchikawa C, Kotliarov Y, Uchida K, Nagao Y, Nagaoka U, Tamaoka A, Oyanagi K, Oyama F, Nukina N. Decreased expression of hypothalamic neuropeptides in Huntington disease transgenic mice with expanded polyglutamine-EGFP fluorescent aggregates. J Neurochem. 2005;93:641–653. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine AJ. p53, the cellular gatekeeper for growth and division. Cell. 1997;88:323–331. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81871-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li SH, Cheng AL, Li H, Li XJ. Cellular defects and altered gene expression in PC12 cells stably expressing mutant huntingtin. J Neurosci. 1999;19:5159–5172. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-13-05159.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthi-Carter R, Hanson SA, Strand AD, Bergstrom DA, Chun W, Peters NL, Woods AM, Chan EY, Kooperberg C, Krainc D, Young AB, Tapscott SJ, Olson JM. Dysregulation of gene expression in the R6/2 model of polyglutamine disease: parallel changes in muscle and brain. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:1911–1926. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.17.1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthi-Carter R, Strand A, Peters NL, Solano SM, Hollingsworth ZR, Menon AS, Frey AS, Spektor BS, Penney EB, Schilling G, Ross CA, Borchelt DR, Tapscott SJ, Young AB, Cha JH, Olson JM. Decreased expression of striatal signaling genes in a mouse model of Huntington's disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:1259–1271. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.9.1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier B, Gluba W, Bernier B, Turner T, Mohammad K, Guise T, Sutherland A, Thorner M, Scrable H. Modulation of mammalian life span by the short isoform of p53. Genes Dev. 2004;18:306–319. doi: 10.1101/gad.1162404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meade CA, Deng YP, Fusco FR, Del Mar N, Hersch S, Goldowitz D, Reiner A. Cellular localization and development of neuronal intranuclear inclusions in striatal and cortical neurons in R6/2 transgenic mice. J Comp Neurol. 2002;449:241–269. doi: 10.1002/cne.10295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menalled L, Zanjani H, MacKenzie L, Koppel A, Carpenter E, Zeitlin S, Chesselet MF. Decrease in striatal enkephalin mRNA in mouse models of Huntington's disease. Exp Neurol. 2000;162:328–342. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menalled LB. Knock-in mouse models of Huntington's disease. NeuroRx. 2005;2:465–470. doi: 10.1602/neurorx.2.3.465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menalled LB, Sison JD, Dragatsis I, Zeitlin S, Chesselet MF. Time course of early motor and neuropathological anomalies in a knock-in mouse model of Huntington's disease with 140 CAG repeats. J Comp Neurol. 2003;465:11–26. doi: 10.1002/cne.10776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasir J, Floresco SB, O'Kusky JR, Diewert VM, Richman JM, Zeisler J, Borowski A, Marth JD, Phillips AG, Hayden MR. Targeted disruption of the Huntington's disease gene results in embryonic lethality and behavioral and morphological changes in heterozygotes. Cell. 1995;81:811–823. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90542-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan A, Scrable H. Visualization of the dynamics of gene expression in the living mouse. Mol Imaging. 2004;3:33–42. doi: 10.1162/15353500200403193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saudou F, Finkbeiner S, Devys D, Greenberg ME. Huntingtin acts in the nucleus to induce apoptosis but death does not correlate with the formation of intranuclear inclusions. Cell. 1998;95:55–66. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81782-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahbazian MD, Orr HT, Zoghbi HY. Reduction of Purkinje cell pathology in SCA1 transgenic mice by p53 deletion. Neurobiol Dis. 2001;8:974–981. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2001.0444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp AH, Loev SJ, Schilling G, Li SH, Li XJ, Bao J, Wagster MV, Kotzuk JA, Steiner JP, Lo A, et al. Widespread expression of Huntington's disease gene (IT15) protein product. Neuron. 1995;14:1065–1074. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90345-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieradzan KA, Mann DM. The selective vulnerability of nerve cells in Huntington's disease. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2001;27:1–21. doi: 10.1046/j.0305-1846.2001.00299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sipione S, Rigamonti D, Valenza M, Zuccato C, Conti L, Pritchard J, Kooperberg C, Olson JM, Cattaneo E. Early transcriptional profiles in huntingtin-inducible striatal cells by microarray analyses. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:1953–1965. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.17.1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slow EJ, Graham RK, Osmand AP, Devon RS, Lu G, Deng Y, Pearson J, Vaid K, Bissada N, Wetzel R, Leavitt BR, Hayden MR. Absence of behavioral abnormalities and neurodegeneration in vivo despite widespread neuronal huntingtin inclusions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:11402–11407. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503634102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyner SD, Venkatachalam S, Choi J, Jones S, Ghebranious N, Igelmann H, Lu X, Soron G, Cooper B, Brayton C, Hee Park S, Thompson T, Karsenty G, Bradley A, Donehower LA. p53 mutant mice that display early ageing-associated phenotypes. Nature. 2002;415:45–53. doi: 10.1038/415045a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogelstein B, Lane D, Levine AJ. Surfing the p53 network. Nature. 2000;408:307–310. doi: 10.1038/35042675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young PJ, Day PM, Zhou J, Androphy EJ, Morris GE, Lorson CL. A direct interaction between the survival motor neuron protein and p53 and its relationship to spinal muscular atrophy. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:2852–2859. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108769200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeitlin S, Liu JP, Chapman DL, Papaioannou VE, Efstratiadis A. Increased apoptosis and early embryonic lethality in mice nullizygous for the Huntington's disease gene homologue. Nat Genet. 1995;11:155–163. doi: 10.1038/ng1095-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Li M, Drozda M, Chen M, Ren S, Mejia Sanchez RO, Leavitt BR, Cattaneo E, Ferrante RJ, Hayden MR, Friedlander RM. Depletion of wild-type huntingtin in mouse models of neurologic diseases. J Neurochem. 2003;87:101–106. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao T, Chang LW, McLeod HL, Stormo GD. PromoLign: a database for upstream region analysis and SNPs. Hum Mutat. 2004;23:534–539. doi: 10.1002/humu.20049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker B, Luthi-Carter R, Kama JA, Dunah AW, Stern EA, Fox JH, Standaert DG, Young AB, Augood SJ. Transcriptional dysregulation in striatal projection- and interneurons in a mouse model of Huntington's disease: neuronal selectivity and potential neuroprotective role of HAP1. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:179–189. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]