Abstract

A Klebsiella pneumoniae strain resistant to third-generation cephalosporins was isolated in the eastern Netherlands. The strain was found to carry a novel extended-spectrum β-lactamase, namely, SHV-31. The combination of the two mutations by which SHV-31 differs from SHV-1, namely, L35Q and E240K, had previously only been described in association with one or more additional mutations.

The Netherlands is well known for its low antibiotic consumption (4) and low prevalence of multidrug resistance, including that caused by gram-negative bacteria producing extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) (3, 5, 13). The overall prevalence of ESBL-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates (TEM- and SHV-type ESBLs) was less than 1% in 1997 (13). In a study designed to determine the incidences of ESBL-producing vancomycin-resistant Enterococus faecium and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from 38 centers across the world during 2001 to 2002, the overall ESBL production rate for the combined Enterobacteriaceae isolates was lowest in The Netherlands, amounting to 2.0%, as against an average of 10.5% in other countries (1).

Among intensive care unit (ICU) isolates collected for a European multicenter study, the prevalence of ESBL-producing Klebsiella strains in three Dutch hospitals was as high as 16% (eight times higher than the general prevalence), but still far lower than the average prevalence in other European countries (7).

A K. pneumoniae strain, KPN15-NL, resistant to extended-spectrum cephalosporins, aminoglycosides, and fluoroquinolones, was isolated in August 2001 from a wound culture from an ICU trauma patient admitted to a tertiary-care 1,000-bed teaching hospital (18-bed ICU) situated in the easternmost part of The Netherlands. The strain was identified with biochemical tests by means of API ID32E (bioMérieux). The patient had never been hospitalized before. By the end of 2002, Klebsiella strains with the same antibiotic resistance profile and with the same randomly amplified polymorphic DNA and restriction fragment length polymorphism patterns were isolated from a total of 85 ICU patients, thus making KPN15-NL the index isolate of a large epidemic.

Susceptibility testing, carried out according to the latest CLSI (formerly NCCLS) guidelines (2), proved K. pneumoniae KPN15-NL to be resistant to extended-spectrum cephalosporins. The Kirby-Bauer test revealed features typical of an ESBL-producing strain, namely, resistance to ceftazidime, cefotaxime, and aztreonam, but susceptibility to cefepime, and reversal of these resistances by clavulanic acid. The isolate was also tested for its antimicrobial susceptibilities by broth microdilution. The resulting β-lactam MICs are reported in Table 1. The isolate also proved resistant to gentamicin (64 μg/ml), but not to amikacin (8 μg/ml), and resistant to fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin, >128 μg/ml, and levofloxacin, 128 μg/ml).

TABLE 1.

MICs for K. pneumoniae KPN-15-NL and E. coli XL10

| Antimicrobial(s) | MIC (μg/ml) for:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| KPN15-NL | E. coli XL10/vector | E. coli XL10/pSHV-31 | |

| Ampicillin | >128 | 2 | >128 |

| Amoxicillin | >128 | 16 | >128 |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid | 32 | 8 | 8 |

| Piperacillin | >128 | 1 | 64 |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | 16 | 1 | 4 |

| Cefoxitin | 16 | 1 | 1 |

| Ceftazidime | 128 | 0.12 | 32 |

| Ceftazidime-clavulanic acid | 8 | 0.12 | 4 |

| Cefotaxime | 8 | ≤0.06 | 4 |

| Cefepime | 1 | ≤0.06 | 0.5 |

| Aztreonam | >128 | 0.12 | >128 |

| Imipenem | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 |

| Ertapenem | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 |

The β-lactamase production was first confirmed by isoelectric focusing, performed in a precast polyacrylamide (5%) gel containing ampholines (pH range, 3.5 to 9.0) (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden) on a biophoresis apparatus (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The enzyme activity was revealed by overlaying the gel with a paper filter soaked in 250 μM nitrocefin (Oxoid, Basingstoke, Hampshire, England). When inhibition with clavulanic acid was tested, the gel was previously overlaid with a paper filter soaked in 2 μg/ml of clavulanic acid. The strain showed two bands, at pI 5.4 and 7.8; both bands were inhibited by clavulanic acid in the overlay test (data not shown).

The presence of blaTEM, blaSHV, blaCTX-M, and blaOXA resistance genes was checked by PCR using recombinant Taq polymerase (Amersham Biosciences) and specific oligonucleotide primers as follows: TEM-FW and TEM-REV, specific for blaTEM (8); SHV-FW and SHV-REV, specific for blaSHV (10); CTX-MU1 and CTX-MU2, specific for blaCTX-M (9); and OXA1F/R, OXA2F/R, and OXA10F/R, specific for blaOXA (12).

PCR products were purified using a QIAGEN microspin (QIAGEN GmbH, Hilden, Germany). We obtained products for blaTEM and for blaSHV. The entire coding regions were amplified. DNA sequencing of the amplicons obtained was performed on both strands and analyzed in an ABI PRISM 377 DNA sequencer. The TEM product proved to be a TEM-1 enzyme, which was consistent with the pI 5.4 isoelectric focus band. The SHV product showed two amino acid changes compared with SHV-1, namely, L35Q and E240K. Thus, KPN15-NL turned out to harbor a novel SHV enzyme, which has been termed SHV-31 by the Lahey Clinic (http://www.lahey.org/studies).

The SHV gene was cloned in the phagemid vector pPCR script Cam SK+ (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The entire SHV gene was amplified by PCR with the following primers: SHV-CF (5′ GGGGAATTCTTATTTGTCGC) and SHV-CR (5′ CAGAATTCGCTTAGCGTTGCCAGT). The primers extended beyond the coding sequence to give the polishing protocol some extra DNA.

The PCR product was ligated with the phagemid vector pPCR script Cam SK+. This cloning vector has a chloramphenicol resistance gene and a lac promoter for gene expression (also driving blaSHV-31 expression). The cloning site was SfiI. Ligated vectors were transformed in E. coli XL10 ultracompetent cells by the ligation kit polishing protocol (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Transformants were selected on LB agar plates with 30 μg/ml of chloramphenicol and 2 μg/ml of ceftazidime added and then checked by PCR and endonuclease digestion.

Upon isoelectric focusing, the E. coli XL10/pSHV-31 strain showed a band of pI 7.8, and its MICs for extended-spectrum cephalosporins paralleled those of K. pneumoniae KPN15-NL, differing sharply from those of E. coli XL10 for all β-lactams tested (ampicillin, >64-fold; ceftazidime, 256-fold; cefotaxime, >64-fold; cefepime, >8-fold; and aztreonam, >1,000-fold).

We also performed bacterial conjugation experiments using E. coli J53 AzR as the recipient strain and selecting with 100 μg/ml of sodium azide and 2 μg/ml of ceftazidime. After all attempts at conjugation had failed, including those involving electroporation, and in order to investigate where the SHV-31 gene of K. pneumoniae KPN15-NL was located, plasmid DNA was extracted from both K. pneumoniae KPN15-NL and E. coli XL10/pSHV-31.

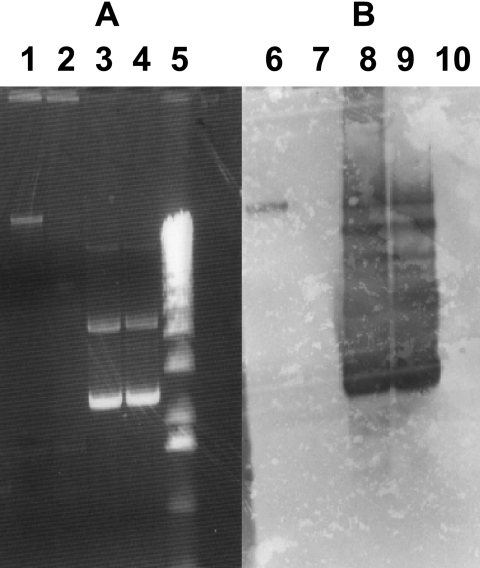

Plasmid extraction from KPN15-NL and XL10/pSHV-31 was performed by means of the alkaline lysis method. One-half of each plasmid sample was treated with plasmid-safe DNase (Epicenter Technologies) to remove contaminating chromosomal DNA. The plasmids were separated by electrophoresis in a 0.6% agarose gel. Plasmid profile gels were stained with ethidium bromide (Fig. 1A). Southern analysis was performed by standard methods (11) (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Analysis of localization of the blaSHV-31 gene. The figure shows an agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide (A) and a Southern blot (B). Lanes 1 and 6, plasmid DNA extracted from KPN15-NL; lanes 2 and 7, plasmid DNA extracted from KPN15-NL, treated with plasmid-safe DNase; lanes 3 and 8, DNA from a plasmid carrying the blaSHV-31 gene, extracted from the host strain E. coli XL10; lanes 4 and 9, DNA from a plasmid carrying the blaSHV-31 gene, extracted from the host strain E. coli XL10 and treated with plasmid-safe DNase; lanes 5 and 10, 1-kb marker (Invitrogen).

The blaSHV-31-specific probe was synthesized by using the SHV-31 primers and incorporating digoxigenin-11-dUTP (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) into the PCR product. The probe reacted only with the plasmid preparation not treated with plasmid-safe DNase, and therefore, we assume that the SHV-31 gene has a chromosomal localization.

The two amino acid mutations found in the SHV gene, namely, L35Q and E240K, have been found previously in other SHV genes either alone or as a pair. However, in the latter case, one or more further mutations were also reported.

The outbreak of the K. pneumoniae strain resistant to extended-spectrum cephalosporins mentioned in the present study started in August 2001 and by the end of 2002 had involved a total of 85 ICU patients. After that, the strain became hyperendemic in the center and is presently still a frequent cause of nosocomial infection in the affected hospital.

Outbreaks of K. pneumoniae producing ESBLs are very rare in The Netherlands. Gruteke et al. (5) previously reported an outbreak of multiresistant K. pneumoniae harboring SHV-5 in a Dutch 250-bed care facility between March 1997 and June 1999.

Recent data from The Netherlands clearly show the great diversity of ESBL genes in 34 nonduplicate Salmonella enterica strains isolated in 2001 and 2002 from poultry, poultry products, and human patients and seem to confirm that many of these genes appear to spread rapidly (6).

The occurrence of clinical outbreaks, the diversity of the genes involved and their rapid spread, the finding of novel enzymes, and the presence of ESBLs also in animals and in animal products all contribute to making ESBLs a matter of serious concern even in The Netherlands.

Protein structure accession number.

The GenBank accession number for the novel SHV enzyme termed SHV-31 is AY277255.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by grant 2005061894 (COFIN 2005) from the Italian Ministry of University and Research.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 18 December 2006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bouchillon, S. K., B. M. Johnson, D. J. Hoban, J. L. Johnson, M. J. Dowzicky, D. H. Wu, M. A. Visalli, and P. A. Bradford. 2004. Determining incidence of extended spectrum beta-lactamase producing Enterobacteriaceae, vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in 38 centres from 17 countries: the PEARLS study 2001-2002. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 24:119-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2005. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; 16th informational supplement. CLSI document M100-S16. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA.

- 3.European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System (EARSS). 2005. EARSS annual report 2004. Bilthoven, The Netherlands. http://www.earss.rivm.nl.

- 4.Goossens, H., M. Ferech, R. Vander Stichele, M. Elsevier, et al. 2005. Outpatient antibiotic use in Europe and association with resistance: a cross-national database study. Lancet 365:579-587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gruteke, P., W. Goessens, J. V. VanGils, P. Peerbooms, N. Lemmens-DenToom, M. Van Santen-Verhenvel, A. Van Belkum, and H. Verbrugh. 2003. Patterns of resistance associated with integrons, the extended-spectrum β-lactamase SHV-5 gene, and a multidrug efflux pump of Klebsiella pneumoniae causing a nosocomial outbreak. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:1161-1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hasman, H., D. Mevius, K. Veldman, I. Olesen, and F. M. Aarestrup. 2005. Beta-lactamases among extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-resistant Salmonella from poultry, poultry products and human patients in The Netherlands. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 56:115-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Livermore, D. M., and M. Yuan. 1996. Antibiotic resistance and production of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases amongst Klebsiella spp. from intensive care units in Europe. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 38:409-424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mabilat, C., and S. Goussard. 1993. PCR detection and identification of genes for extended-spectrum β-lactamases, p. 553-563. In D. H. Persing, T. F. Smith, F. C. Tenover, and T. J. White (ed.), Diagnostic molecular microbiology: principles and applications. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC.

- 9.Pagani, L., E. Dell'Amico, R. Migliavacca, M. M. D'Andrea, E. Giacobone, G. Amicosante, E. Romero, G. M. Rossolini. 2003. Multiple CTX-M-type extended-spectrum β-lactamases in nosocomial isolates of Enterobacteriaceae from a hospital in northern Italy. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:4264-4269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rasheed, J. K., C. Jay, B. Metchock, F. Berkowitz, L. Weigel, J. Grellin, C. Steward, B. Hill, A. A. Medeiros, and F. C. Tenover. 1997. Evolution of extended-spectrum β-lactam resistance (SHV-8) in a strain of Escherichia coli during multiple episodes of bacteremia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:647-653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 12.Steward, C. D., J. K. Rasheed, S. K. Hubert, J. W. Biddle, P. M. Raney, G. J. Anderson, P. P. Williams, L. L. Brittain, A. Oliver, J. E. McGowan, Jr., and F. C. Tenover. 2001. Characterization of clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae from 19 laboratories using the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards extended-spectrum β-lactamase detection methods. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2864-2872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stobberingh, E. E., J. Arends, J. A. Hoogkamp-Korstanje, W. H. Goessens, A. G. Buiting, M. R. Visser, Y. Ossenkopp, J. DeBets, R. J. Van-Kell, M. L. Van Ogtrop, L. J. Sabbe, G. P. Voorn, H. L. Winter, and J. H. Van Zeijl. 1999. Occurrence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBL) in Dutch hospitals. Infection 27:348-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]