Abstract

These Best Practice Guidelines on Publication Ethics describe Blackwell Publishing's position on the major ethical principles of academic publishing and review factors that may foster ethical behavior or create problems. The aims are to encourage discussion, to initiate changes where they are needed, and to provide practical guidance, in the form of Best Practice statements, to inform these changes. Blackwell Publishing recommends that editors adapt and adopt the suggestions outlined to best fit the needs of their own particular publishing environment.

Background

Academic publishing depends, to a great extent, on trust. Editors trust peer reviewers to provide fair assessments, authors trust editors to select appropriate peer reviewers, and readers put their trust in the peer-review process. Academic publishing also occurs in an environment of powerful intellectual, financial, and sometimes political interests that may collide or compete. Good decisions and strong editorial processes designed to manage these interests will foster a sustainable and efficient publishing system, which will benefit academic societies, journal editors, authors, research funders, readers, and publishers. Good publication practices do not develop by chance, and will become established only if they are actively promoted.

These Best Practice Guidelines on Publication Ethics have been written to offer journal editors a framework for developing and implementing their own publication ethics policies and systems. In some sectors, notably medicine, the debate about publication ethics is moving rapidly. In response, and at suitable intervals, we will update our guidance. The general principles of publication ethics are grouped and discussed under broad themes. Statements of principle are followed by factors that may affect them. The order of the sections does not imply a hierarchy of importance.

Transparency

Who funded the work?

Readers have a right to know who funded a research project or the publication of a document.

Research funders should be listed on all research papers.

Funding for any type of publication, for example, by a commercial company, charity or government department, should be stated within the publication. This applies to all types of papers (including, for example, research papers, review papers, letters, editorials, commentaries).

The role of the research funder, as well as the role of all parties contributing to the research and publication, in designing the research, recruiting investigators/authors, collecting the data, analyzing the data, preparing the manuscript or controlling publication decisions should be stated in the publication, unless this is obvious from the list of authors/contributors.

Other sources of support for publications should be clearly identified in the manuscript, usually in an acknowledgment. For example, these might include funding for Blackwell Publishing OnlineOpen (open access) publication, or funding for writing or editorial assistance.

See Box 1

Box 1. Best Practice: Transparency

Sources of funding for research or publication should always be disclosed. Editors should state this directly in their editorial policy. Authors should routinely include information about research funding in all papers they prepare for publication. Where a clinical trial registration number is available, this should be included.

Who did the work?

The list of authors should accurately reflect who did the work. All published work should be attributed to one or more authors.

Journal instructions for authors should explain the concepts of academic authorship, setting out which contributions do and do not qualify for authorship.

Journals should remind contributors about authorship guidelines [for example, the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria (1)] and should encourage their adherence by appropriately designed authorship declarations.

Listing individuals’ contributions to the research and publication process provides greater transparency than the traditional listing of authors and may discourage inappropriate authorship practices such as ‘ghost’ authors (individuals who qualify for authorship but are not listed) and ‘guest’ (or honorary) authors (individuals who are listed despite not qualifying for authorship, such as heads of department not directly involved with research).

Editors should ask for a declaration that all authors meet the journal's criteria for authorship and that nobody who meets these criteria has been omitted from the list.

Editors should ask for a declaration that the authors have acknowledged all significant contributions made to their publication by individuals who did not meet the journal's criteria for authorship. These might include, for example and depending on their contribution, author's editors, statisticians, medical writers, or translators.

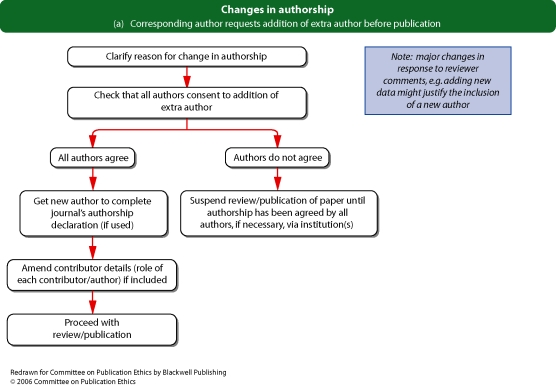

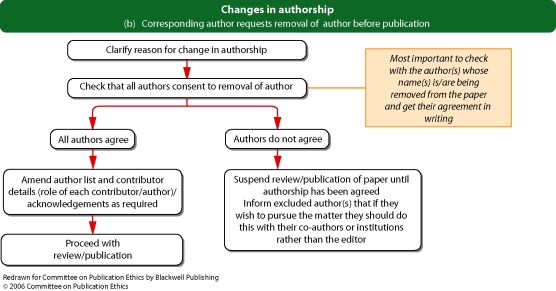

If an authorship dispute or discrepancy comes to light before publication (for example, changes to the list of authors are proposed after submission), editors should take care to explain the journal's authorship policy to the corresponding author and to establish that all authors agree to the change before proceeding with publication.

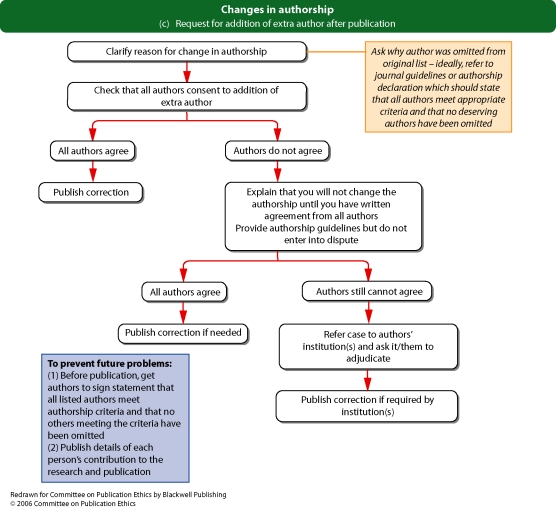

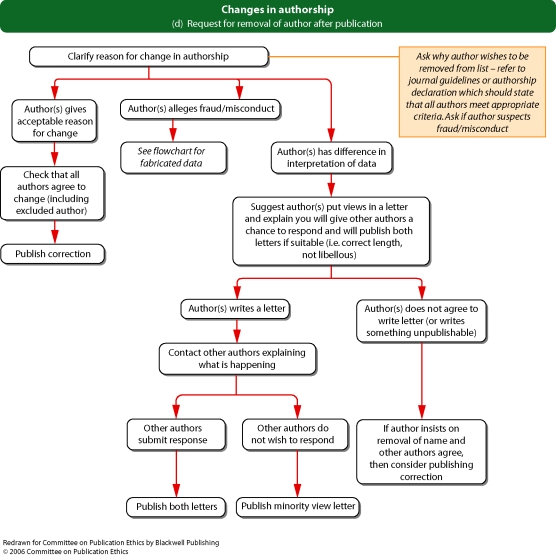

If an authorship dispute emerges after publication (for example, somebody contacts the editor claiming they should have been an author of a published paper, or requesting that their name be withdrawn from a paper), the editor should contact the corresponding author and, where possible, the other authors to establish the veracity of the case.

If authorship policies have been clearly set out and an explicit authorship declaration(s) has been received (stating that all authors meet agreed criteria and that nobody deserving authorship has been omitted), then genuine errors are unlikely – however, editors should consider publishing a correction in the case of such errors.

See Flowcharts 1a–d (pp. 13–15) ‘Changes in authorship’ from Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE).

Box 2. Best Practice: Authorship and acknowledgment

The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) provides a definition of authorship that is applicable beyond the medical sector (1). Blackwell Publishing recommends that journal editors consider adopting the ICMJE authorship criteria as part of their editorial policy. The ICMJE authorship criteria state ‘authorship credit should be based on 1) substantial contributions to conception and design, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; 2) drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and 3) final approval of the version to be published. Authors should meet conditions 1, 2 and 3.’

Blackwell Publishing recommends that editors ask authors to submit a short description of all contributions to their manuscript. Each author's contribution should be described in brief. Authors of research papers should state whether they had complete access to the study data that support the publication. Contributors who do not qualify as authors should also be listed and their particular contribution described. This information should appear as an acknowledgment.

Sample authorship description/acknowledgment

Drs A, B and C designed and conducted the study, including patient recruitment, data collection, and data analysis. Dr A prepared the manuscript draft with important intellectual input from Drs B and C. All authors approved the final manuscript. [Insert name of organization] provided funding for the study, statistical support in analyzing the data with input from Drs A, B and C, and also provided funding for editorial support. Drs A, B and C had complete access to the study data. We would like to thank Dr D for her editorial support during preparation of this manuscript.

The Blackwell Publishing Exclusive License Form, the OnlineOpen Form, or the Copyright Assignment form, one of which must be submitted before publication in any Blackwell journal, requires the corresponding author to state that written authorization for publication of the article has been received by the corresponding author from all co-authors.

Box 3. Best Practice: Collecting authorship information

For research papers, authorship should be decided at the study launch. Policing authorship is beyond the responsibilities of an editor. Editors should demand transparent and complete descriptions of who has contributed to a paper.

Editors should employ appropriate systems to inform contributors about authorship criteria (if used) and/or to obtain accurate information about individuals’ contributions. Blackwell Publishing can advise Blackwell editors about how best to do this, and the Blackwell Publishing electronic submission system can be used to explain authorship criteria, and to collect and manage authorship information efficiently.

Editors should ask authors to submit, as part of their initial submission package, a statement that all individuals listed as authors meet the appropriate authorship criteria, that nobody who qualifies for authorship has been omitted from the list, and that contributors and their funding sources have been properly acknowledged, and that authors and contributors have approved the acknowledgment of their contribution.

Box 4. Best Practice: Attributing authorship to a group

The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) provides guidance for instances where a number of authors report on behalf of a larger group of investigators (1). This guidance is applicable outside the medical sector. Blackwell Publishing recommends that editors adopt the ICMJE policy. ICMJE guidance states: ‘When a large, multi-center group has conducted the work, the group should identify the individuals who accept direct responsibility for the manuscript. These individuals should fully meet the criteria for authorship defined above… When submitting a group author manuscript, the corresponding author should clearly indicate the preferred citation and should clearly identify all individual authors as well as the group name.’ The individual authors who accept direct responsibility for the manuscript should list the members of the larger authorship group in an appendix to their acknowledgments.

Has the work been published before?

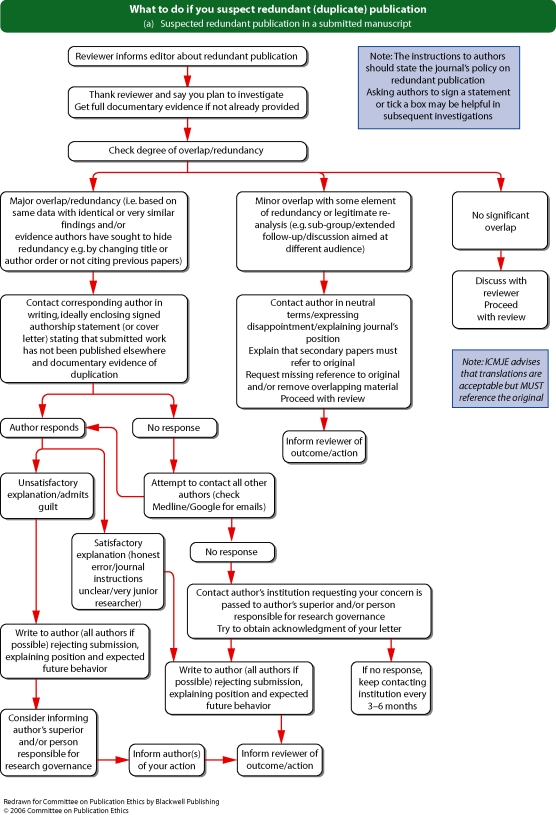

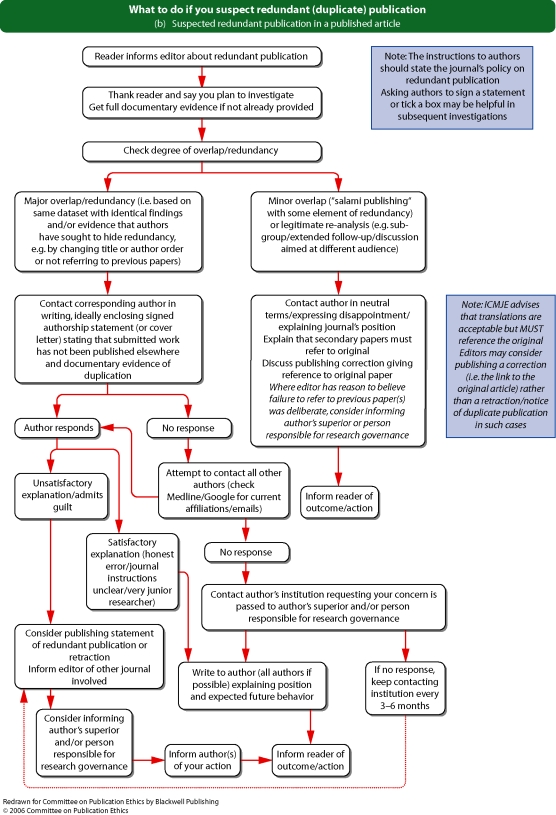

Most journals wish to consider only work that has not been published elsewhere. One reason for this is that the scientific literature can be skewed by redundant publication, with important consequences, for example, if results are inadvertently included more than once into meta-analyses. Both journal editors and readers have a right to know whether research has been published previously.

Journals should ask authors for a declaration that the submitted work and its essential substance have not previously been published and are not being considered for publication elsewhere.

If a primary research report is published and later found to be redundant (i.e. has been published before), the editor should contact the authors and consider publishing a notice of redundant publication.

Editors have a right to demand original work and to question authors about whether opinion pieces (for example, editorials, letters, non-systematic reviews) have been published before; journals should establish a policy about how much overlap is considered acceptable between such publications.

Journals that publish clinical trials should consider making registration a requirement before publication of such trials. Even if a journal does not make clinical trial registration compulsory for publication, editors should encourage clear identification of clinical trials and should have a policy about where such information is presented within the structure of the published article.

Papers that present new analyses or syntheses of data that have already been published (for example, sub-group analyses) should identify the primary data source, including reference to the clinical trial registration number if one is available and full reference to the related primary publications.

See Flowcharts 2a and b (pp. 16 and 17) ‘What to do if you suspect redundant (duplicate) publication’ from Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE).

Read Blackwell Publishing Copyright FAQs section 1.23 ‘What is the situation regarding dual publication?’ (2).

Box 5. Best Practice: Redundant (multiple) publication

Journal instructions should clearly explain what is, and what is not, considered to be prior publication. Abstracts and posters at conferences, results presented at meetings (for example, to inform investigators or participants about findings), results databases (data without interpretation, discussion, context or conclusions in the form of tables and text to describe data/information where this is not easily presented in tabular form) are not considered by Blackwell Publishing to be prior publication.

Journals may choose to accept (i.e. consider ‘not redundant’) the re-publication of materials that have been accurately translated from an original publication in a different language. Journals that translate and publish material that has been published elsewhere should ensure that they have appropriate permission(s), should indicate clearly that the material has been translated and re-published, and should indicate clearly the original source of the material. Editors may request copies of related publications if they are concerned about overlap and possible redundancy. Re-publishing in the same language as primary publication with the aim of serving different audiences is more difficult to justify when primary publication is electronic and therefore easily accessible, but if editors feel that this is appropriate they should follow the same steps as for translation.

Editors should ensure that sub-group analyses, meta- and secondary analyses are clearly identified as analyses of data that have already been published, that they refer directly to the primary source, and that (if available) they include the clinical trial registration number from the primary publication.

The Blackwell Publishing Exclusive License Form, the OnlineOpen Form, or the Copyright Assignment form, one of which must be submitted before publication in any Blackwell journal, requires signature from the corresponding author to warrant that the article is an original work, has not been published before and is not being considered for publication elsewhere in its final form either in printed or electronic form.

Some questions and answers about duplicate publication

Q.‘I am considering joining two of my fellow journal editors in writing a joint editorial about plagiarism and academic disputes. It would be published simultaneously in three journals.’

A.This is appropriate multiple publication. Multiple publication helps convey the strength of the (important) message. Each editorial should refer to the others, as references and in a direct statement.

Q.‘We publish abstracts from specialist societies, then often get the full paper a few months later.’

A.This is not duplicate publication. Abstracts do not present full results/analysis.

Q.‘Our Chinese edition has translated papers from the main journal a few months after the original was published.’

A.This could be appropriate re-publication. Translated papers should make it clear (perhaps in their titles) that they are translated from a primary source, and they should refer directly to the primary source (in their abstract and their text, as a reference, and as a footnote).

Box 6. Best Practice: Registering clinical trials

Since 2005, some medical journals [notably those edited by members of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE)] have made registration in a publicly accessible trial register a requirement for publishing clinical trials (1). The World Health Organization (WHO), in May 2006, urged ‘research institutions and companies to register all medical studies that test treatments on human beings’ (3). ICMJE allowed authors a grace period for registration of new or ongoing trials; this grace period ended September 2005. WHO states that ‘all clinical trials should be registered at inception’, i.e. prospectively before patients/subjects are enrolled, using the complete 20 criteria described by its International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (http://www.who.int/ictrp/en/).

Blackwell Publishing recommends that editors of medical journals require that the clinical trials they consider for publication are registered in free, public clinical trial registries (for example, http://www.clinicaltrials.gov, http://clinicaltrials-dev.ifpma.org/, http://isrctn.org/) before publication. Editors may choose to allow authors submitting to their journals a grace period in which ongoing or completed trials can be registered. Editors should develop policies about trial registration that suit their own particular publishing environment, and should make their policies about trial registration clear to prospective authors. Even if editors decide that prospective registration is not made compulsory for their journal, journals should encourage clear trial identification and should have a policy for including the clinical trial registration number and name of the trial register within the publication, and perhaps should adapt their electronic submission process to collect this information.

Sample wording for statement in instructions for authors

[Insert journal name] requires that the clinical trials submitted for its consideration are registered in a publicly accessible database. Authors should include the name of the trial register and their clinical trial registration number at the end of their abstract. If you wish the editor[s] to consider an unregistered trial please explain briefly why the trial has not been registered.

Promoting research integrity

Research misconduct

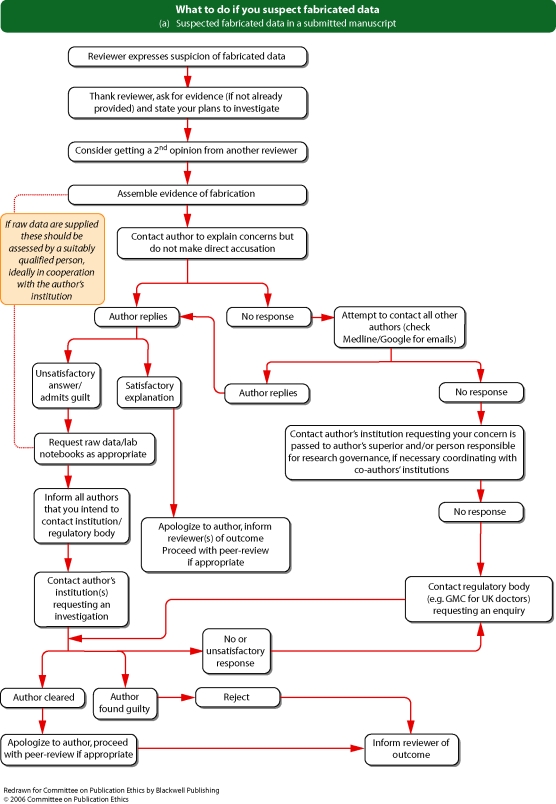

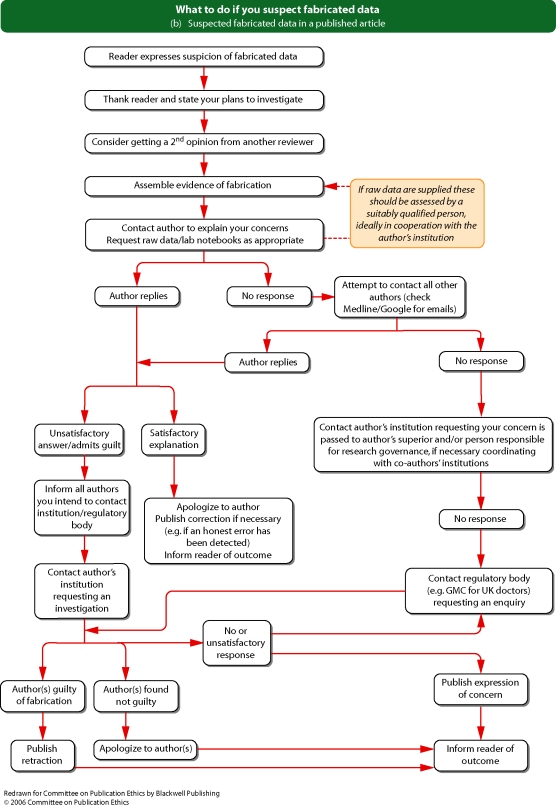

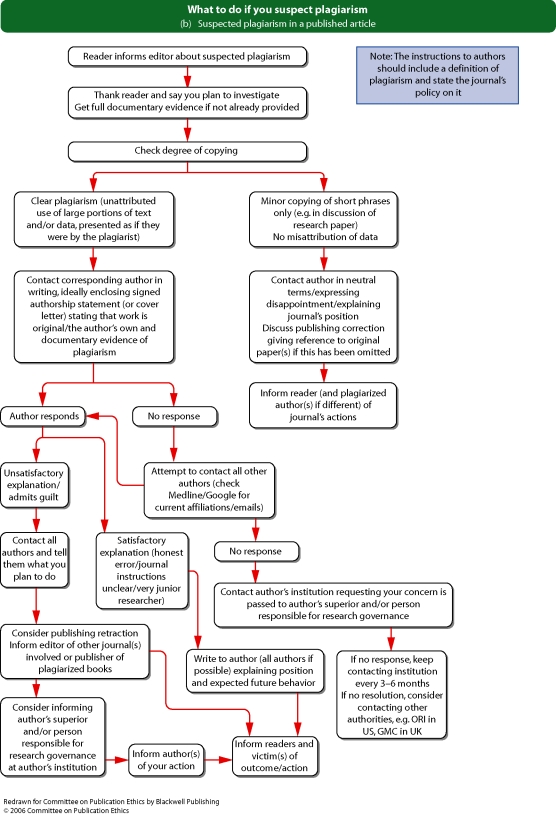

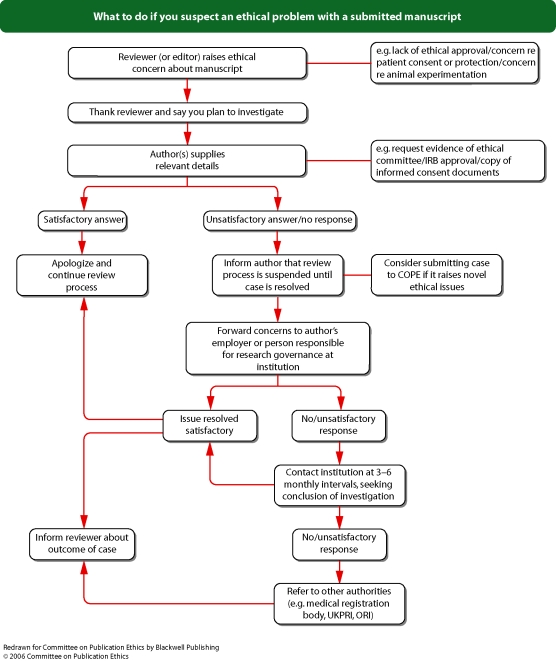

If editors suspect research misconduct (for example, data fabrication, falsification or plagiarism), they should attempt to ensure that this is properly investigated by the appropriate authorities.

Peer review sometimes reveals suspicion of misconduct. Editors should inform peer reviewers about this potential role.

If peer reviewers raise concerns of serious misconduct (for example, data fabrication, falsification, inappropriate image manipulation, or plagiarism), these should be taken seriously. However, authors have a right to respond to such allegations and for investigations to be carried out with appropriate speed and due diligence.

Journals are not usually in a position to investigate misconduct allegations themselves, but editors have a responsibility to alert appropriate bodies (for example, employers, funders, regulatory authorities) and encourage them to investigate.

Read more: The US Office of Research Integrity Managing Allegations of Scientific Misconduct: A Guidance Document for Editors (4). Committee on Publication Ethics Code of Conduct (5). UK Panel for Research Integrity in Health and Biomedical Sciences (6).

See Flowcharts 3a and b (pp. 18 and 19) ‘What to do if you suspect fabricated data’ and Flowcharts 4a and b (pp. 20 and 21) ‘What to do if you suspect plagiarism’ from Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE).

Protecting the rights of research participants/subjects

Editors should create publication policies that promote ethical and responsible research practices.

Journal instructions should include links to relevant frameworks such as the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki for clinical trials (7).

Editors should make clear the standards that they require. Authors’ national standards for research practices (in human and animal studies) may be appropriate.

Editors should seek assurances that studies have been approved by relevant bodies (for example, institutional review board, research ethics committee, data and safety monitoring board, regulatory authorities including those overseeing animal experiments).

Editors should encourage peer reviewers to consider ethical issues raised by the research they are reviewing. Editors should request additional information from authors if they feel this is required.

See Box 7.

Box 7. Best Practice: Protecting research subjects, patients and experimental animals

Policing the standards of human or animal research is beyond the responsibilities of an editor. Even so, medical journals can encourage authors to follow the highest standards and may consider requiring, for example, statements from authors that trials conformed to Good Clinical Practice [for example, US Food and Drug Administration Good Clinical Practice in FDA-Regulated Clinical Trials (8); UK Medicines Research Council Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice in Clinical Trials (9)] and/or the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki (7).

Journals should ask authors to state that the study they are submitting was approved by the relevant research ethics committee or institutional review board. If human participants were involved, manuscripts must be accompanied by a statement that the experiments were undertaken with the understanding and appropriate informed consent of each. If experimental animals were used, the materials and methods (experimental procedures) section must clearly indicate that appropriate measures were taken to minimize pain or discomfort, and details of animal care should be provided. Blackwell Publishing suggests that all these standards are defined by the lead investigator's national standards.

Editors should reserve the right to reject papers if there is doubt whether appropriate procedures have been followed. If a paper has been submitted from a country where there is no ethics committee, institutional review board, or similar review and approval, editors should use their own experience to judge whether the paper should be published. If the decision is made to publish a paper under these circumstances a short statement should be included to explain the situation.

Where individual human subjects or case studies are discussed (for example, as in medicine, psychology, criminology), journals should protect confidentiality and should not permit publication of items that might upset or harm participants/subjects, or breach confidentiality of, for example, the doctor–patient relationship.

Journals should have policies about publishing individual information and identifiable images from patients/human subjects. The best policy is to require explicit consent from any patients described in case studies or shown in photographs.

See Box 8.

Box 8. Best Practice: Respecting confidentiality

In the majority of cases, editors should only consider publishing information and images from individual participants/subjects or patients where the authors have obtained the individual's explicit consent. Exceptional cases may arise where gaining the individual's explicit consent is not possible but where publishing an individual's information or image can be demonstrated to have a genuine public health interest. In cases like this, before taking any action editors should seek and follow council from the journal owner, Blackwell Publishing and/or legal professionals.

In the case of technical images (for example, radiographs, micrographs) editors should ensure that all information that could identify the subject has been removed from the image.

Respecting cultures and heritage

Editors should exercise sensitivity when publishing images of objects that might have cultural significance or cause offence (for example, Australian aboriginal remains held in museums, religious texts, historical events). It may be acceptable to publish images of human remains (for example, Egyptian mummies, Roman remains) so long as these considerations are respected, despite the fact that for archeological specimens it is impossible to obtain consent from the individual or their descendants.

Informing readers about research and publication misconduct

Editors should inform readers if ethical breaches have occurred. Blackwell Publishing has published general advice on publishing retractions.

Journals should publish ‘retractions’ if work is proven to be fraudulent, or ‘expressions of concern’ if editors have well-founded suspicions of misconduct.

See Box 9.

Read Blackwell Publishing Copyright FAQs section 1.22 ‘What is the situation regarding retractions?’ (10).

Box 9. Best Practice: Errata, Retractions, Expressions of concern

Journals have a duty to publish corrections (errata) when errors could affect the interpretation of data or information, whatever the cause of the error (i.e. arising from author errors or from editorial mishaps). Likewise, journals should publish ‘retractions’ if work is proven to be fraudulent, or ‘expressions of concern’ if editors have well-founded suspicions of misconduct.

The title of the erratum, retraction, or expression of concern should include the words ‘Erratum’, ‘Retraction’, or ‘Expression of concern’.

It should be published on a numbered page (print and electronic) and should be listed in the journal's table of contents.

It should cite the original article.

It should enable the reader to identify and understand the correction in context with the errors made, or should explain why the article is being retracted, or should explain the editor's concerns about the contents of the article.

It should be linked electronically with the original electronic publication, wherever possible.

It should be in a form that enables indexing and abstracting services to identify and link errata, retractions, and expressions of concern to their original publications.

Editorial standards and processes

Peer-review systems

Editors have a responsibility for ensuring the peer-review process is fair and should aim to minimize bias.

The merits of different peer-review systems (for example, revealing peer reviewers’ identities to authors and/or attempting to mask authors’ identities from peer reviewers) have been the subject of considerable debate and study. Findings are contradictory and there is no clear evidence of the superiority of any one system over another. The benefits and feasibility of different systems probably vary between disciplines. Editors should choose a peer-review system that best suits their journal.

Journals should have clearly set-out policies to explain the type of peer review they use (for example, blinded, non-blinded, multiple reviewers) and to explain whether peer review varies between types of article. Systems differ between journals (one system, for example, would be to state that editorials and letters are not peer reviewed, and that research articles and review articles are always peer reviewed). Material that has not been peer reviewed should be clearly identified (for example, in a short description of different types of content in instructions for authors).

Editors should apply consistent standards in their peer-review processes.

If discussions between an author, editor, and peer reviewer have taken place in confidence, they should remain in confidence unless explicit consent has been given by all parties or there are exceptional circumstances (for example, when they might help substantiate claims of intellectual property theft during peer review –‘Peer reviewer conduct and intellectual property’, p. 12).

Editors or board members should never be involved in editorial decisions about their own work. Journals should have clearly set-out policies for handling submissions from members of their editorial board or employees. Some journals will not consider original research papers from editors or employees of the journal. Others have special procedures for ensuring fair peer review in these instances.

Journal editors, members of editorial boards and other editorial staff (including peer reviewers – see ‘Peer reviewer selection and performance’, p. 12) should withdraw from discussions about submissions where any circumstances might prevent them offering unbiased editorial decisions. See ‘Conflicts of interest’, p. 8.

- See Box 10.

Box 10. Best Practice: Publishing work from a journal's own staff

When making editorial decisions about peer reviewed articles where an editor is an author or is acknowledged as a contributor, journals should have mechanisms that ensure that the affected editors or staff members exclude themselves and are not involved in the publication decision. In these cases, a short statement explaining the process used to make the editorial decision should be included. When editors are presented with papers where their own interests may impair their ability to make an unbiased editorial decision, they should deputize decisions about the paper to a suitably qualified individual. See ‘Conflicts of interest’, p. 8. See Flowchart 5 (p. 22) ‘What to do if you suspect an ethical problem with a submitted manuscript’ from Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE).

Peer reviewer selection and performance

Editors have a responsibility to ensure a high standard of objective, unbiased, and timely peer review.

Editors should strive to establish and maintain a database of suitably qualified peer reviewers.

Editors should consider objectively monitoring the performance of peer reviewers/editorial board members and recording the quality and timeliness of their reviews. Editors should ignore rude, defamatory peer review. Peer reviewers who repeatedly produce poor quality, tardy, abusive or unconstructive reviews should not be used again.

Editors should encourage peer reviewers to identify if they have a conflict of interest with the material they are being asked to review, and editors should ask that peer reviewers decline invitations requesting peer review where any circumstances might prevent them producing fair peer review. See ‘Conflicts of interest’, p. 8.

If authors request that an individual (or individuals) does not peer review their paper, editors should use this information to inform their choice of peer reviewer.

Editors may choose to use peer reviewers suggested by authors, but should not consider suggestions made by authors as binding.

Editors should request that peer reviewers who delegate peer review to members of their staff inform the editor when this occurs.

See Box 11.

See ‘Peer reviewer conduct and intellectual property’, p. 12.

Read more: Ethics of Peer Review: A Guide for Manuscript Reviewers, from the US Office of Research Integrity (ORI) by Yale University (11).

Box 11. Best Practice: Timing of publication

Editors should aim to ensure timely peer review and publication for papers they receive, especially where, to the extent that this can be predicted, findings may have important implications. Authors should be aware that priority publication is most likely for papers that, as judged by the journal's editorial staff, may have important implications. The timing of publication may also be influenced by themed issues or if editors group submissions on a similar topic which, inevitably, prevents them from being published in the order that articles were accepted. Online publication prior to print publication (Blackwell Publishing OnlineEarly publication, or OnlineAccepted publication) can provide the fastest route to publication and, therefore, to placing research (and other) information in the public domain.

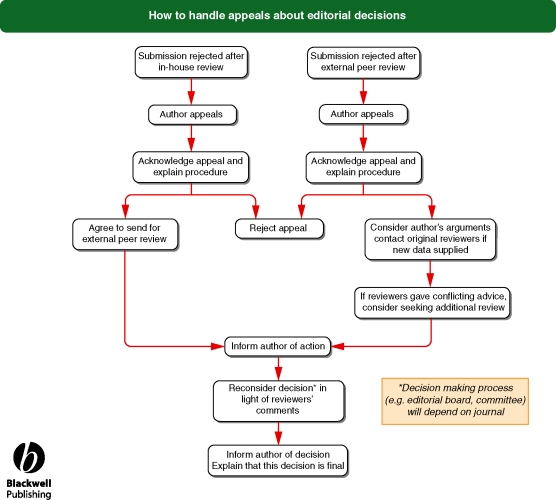

Appeals

Authors have a right to appeal editorial decisions.

Journals should establish a mechanism for authors to appeal peer review decisions. Explaining such a system clearly in the journal's instructions may benefit both authors and editors (for example, by discouraging repeated or unfounded appeals).

Editors should mediate all exchanges between authors and peer reviewers during the peer-review process (i.e. prior to publication). If agreement cannot be reached, editors should consider inviting comments from additional peer reviewer(s), if the editor feels that this would be helpful. Journals should consider stating in their guidelines that the editor's decision following such an appeal is final.

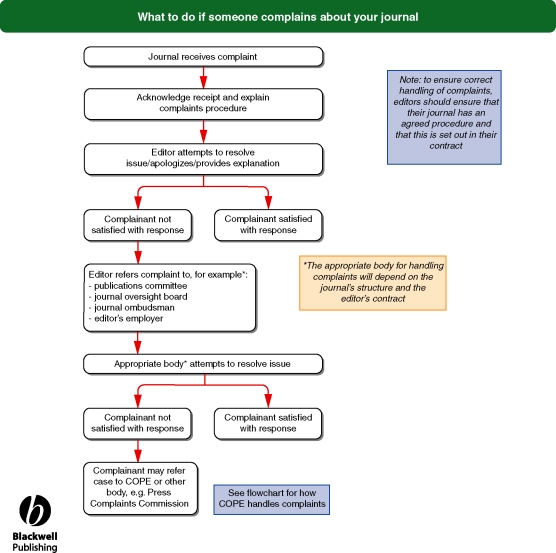

Journals should consider having a mechanism for authors (and others) to comment on aspects of the journal's management.

See Flowchart 6 (p. 23) ‘How to handle appeals’ and Flowchart 7 (p. 24) ‘What to do if someone complains about your journal’.

Conflicts of interest

Editors, authors, and peer reviewers have a responsibility to disclose interests that might appear to affect their ability to present or review data objectively. These include relevant financial (for example, patent ownership, stock ownership, consultancies, speaker's fees), personal, political, intellectual, or religious interests.

‘Financial conflicts may be the easiest to identify but they may not be the most influential.’ Horton R. Lancet (12).

‘We want to try to have a policy that covers all conflicts of interest. Other sources of conflict are personal, political, academic, and religious, and we believe that these may be just as potent as financial conflicts.’ Smith R. BMJ (13).

Editors and board members should, whenever these are relevant to the content being considered or published, declare their interests and affiliations.

Editors should seek disclosure statements from all authors and peer reviewers and should clearly explain the types of conflicts of interest that should be disclosed. Authors’ conflicts of interest (or information describing the absence of conflicts of interest) should be published whenever these are directly or indirectly relevant to the content being published and whenever they are significant. For example, owning USD10 stock in a company that manufactures a product discussed in an article would not be significant, whereas consultancy fees of USD10,000 annually or the equivalent of 5% of an author's gross income from the previous year could be considered significant. Editors may consider not publishing details of authors’ interests when these interests have no relevance to the content being published. If there is doubt about whether conflicts are relevant or significant, it is prudent to disclose.

The existence of a conflict of interest (for example, employment with a research funder) should not prevent someone from being listed as an author if they qualify for authorship. Editors may prefer not to commission subjective articles (for example, editorials or non-systematic reviews) from authors with conflicts of interest. However, arguments can be made that such authors are often well informed and have interesting opinions. Strict policies preventing people with conflicts of interest from publishing opinion pieces may encourage authors to conceal relevant interests, and may therefore be counter-productive.

Readers will benefit from transparency, including knowing authors’ and contributors’ affiliations and interests. Editors should strive to maintain transparent policies and procedures regarding authorship and disclosure of conflicts of interest.

See ‘Transparency’, p. 1.

- See Box 12.

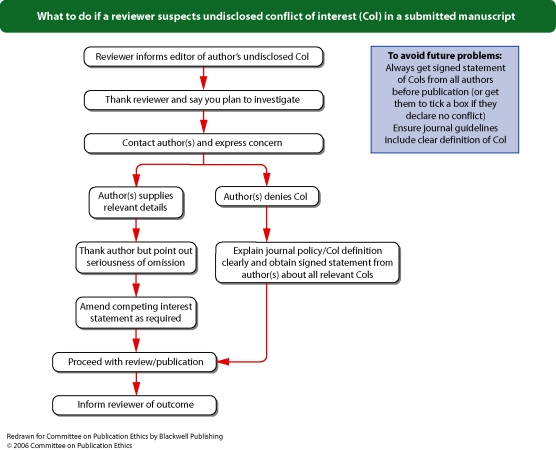

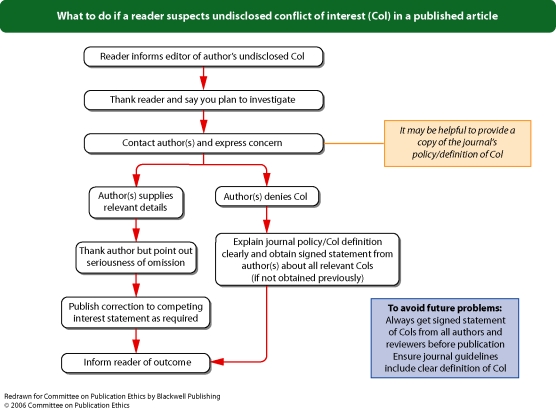

Box 12. Best Practice: Conflicts of interest

Editors should adopt a policy about conflicts of interest that best suits their particular publishing environment, and should describe this in their editorial policy. Editors should adapt their submission processes to encourage submission by authors of the required information. For example, Blackwell Publishing can configure a journal's online submission system to identify submissions without required information, and can return these submissions to authors with an explanation that their submission cannot be processed without completed information.Editors should require statements about conflicts of interest from authors. Editors should explain that these statements should provide information about financial (for example, patent ownership, stock ownership, consultancies, speaker's fees), personal, political, intellectual, or religious interests relevant to the area of research or discussion. Research or publication funding is considered separately (see ‘Who funded the work?’, p. 1).Editors should describe the detail that they require from conflict of interest statements, including the period that these statements should cover (3 years is suggested, but relevant conflicts of interest that are older should not be neglected). When describing financial information, the purpose of the funding received should be described by funding organization (for example, travel grant and speaker's fees received from [name of organization]). Editors could consider using bands (for example, per year, bands for financial disclosures of <USD10,000 and >USD10,000 or the equivalent of <5% and >5% of an author's gross income from the previous year) for authors to describe the level of relevant funding and from which organizations this has been received, or to describe the amount of relevant stocks and shares that they own (not including stocks and shares owned as part of a general, non-specific portfolio).Blackwell Publishing recommends that editors publish the minimum amount of information that will provide context and transparency for readers: the sources and types of funding received by the authors. Editors should always publish a statement to describe authors’ conflicts of interest or, alternatively, a statement that confirms the absence of conflicts of interest. If there is doubt about whether conflicts are relevant, it is prudent to disclose. Authors should routinely provide a statement of conflicts of interest (or lack thereof), whether or not a journal requests this statement.Sample wording[Name of individual] has received fees for serving as a speaker, a consultant and an advisory board member for [names of organizations], and has received research funding from [names of organization]. [Name of individual] is an employee of [name of organization]. [Name of individual] owns stocks and shares in [name of organization]. [Name of individual] owns patent [patent identification and brief description].It is good practice for journal editors, board members and staff (if involved with decisions about publication) to make and regularly update disclosures (either in the journal or via its website) about their relevant interests. See Flowchart 8 (p. 25) ‘What to do if a reviewer suspects undisclosed conflict of interest in a submitted manuscript’, Flowchart 9 (p. 26) ‘What to do if a reader suspects undisclosed conflict of interest in a published article’, and Flowchart 5 (p. 22) ‘What to do if you suspect an ethical problem with a submitted manuscript’ from Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE).

Editorial independence

Editorial independence should be respected. Journal owners (both learned societies and publishers) should not interfere with editorial decisions. The relationship between the editor and the journal owner and publisher should be set out in a formal contract and an appeal mechanism for disputes should be established.

Decisions by editors about whether to publish individual items submitted to a journal should not be influenced by pressure from the editor's employer, the journal owner or the publisher. Ideally, the principles of editorial independence should be set out in the editor's contract. Editors’ contracts at Blackwell Publishing describe the principles of editorial independence.

It is appropriate for journal owners/publishers to discuss general editorial processes and policies with journal editors (for example, whether or not a journal should publish a particular type of article), but they should not get involved in decisions made by the editor about individual articles.

See Box 13.

Read more: Relations between Editors and their Publishing or Sponsoring Societies from the Council of Science Editors (CSE) (14).

Box 13. Best Practice: Commercial issues

Blackwell Publishing does not allow its sales teams to become involved with the editorial decision making process.

The extent of the editorial information available to the sales team and the timing of its disclosure to them will be agreed for each journal with the relevant academic society partners and journal editors. Sales teams may only use this information after editorial decisions are finalized, to provide accurate and timely information to their

potential customers. The positions available for advertising in a journal (for example, within or adjacent to an article, or collected in ‘wells’ within the journal) will be agreed for each journal with the relevant academic society partners and journal editors. Whether it is permissible to sell reprints of OnlineEarly papers (i.e. papers published online prior to print publication) will be agreed for each journal with the relevant academic society partners and journal editors.

Editors, journal owners, and publishers should establish processes that minimize the risk of editorial decisions being influenced by commercial, academic, personal or political factors.

It is often impossible to completely insulate editorial decisions from issues that may influence them, such as commercial considerations. For example, editors will know which articles are likely to attract offprint or reprint sales, but they should judge all submissions on their scientific merit and minimize the influence of other factors. If journals publish advertisements, the sale of advertising must be handled separately from editorial processes.

Journals that publish special issues, supplements or sections (or similar material) funded by third-party organisations should establish policies for how these are handled. The funding organization (the supporter or sometimes sponsor) should not be allowed to influence the selection or editing of submissions, and all funded items should be clearly identified.

All funded material should meet the aims and purposes of the journal carrying the material.

See Box 14.

Box 14. Best Practice: Supplements and other funded publications

Journals may choose to publish supplements, special issues, sections, or similar materials that are funded by a third-party organization, for example, a company, society or charity (the supporter or sometimes sponsor). The content of funded items must align with the purpose of the journal. Journals should consider describing their policy for funded items, should always present readers with the name(s) of the organization(s) funding the publication, and should consider making statements at the beginning and at relevant points within the funded item, including:

Explicit declaration of conflicts of interest or absence thereof for all contributions, including those of both authors and editors (see ‘Conflicts of interest’, p. 8).

Explicit acknowledgment to any contributions (for example, editorial assistance) made by anyone other than named authors, including their affiliations (see ‘Who did the work?’, p. 2).

Description of the processes used to select, review and edit the content, especially the differences in this process, if there are any, from the journal's normal content selection and peer-review processes.

Details of the journal's affiliations and Editorial Board.

Blackwell Publishing recommends that journals appoint co-editors (including the individual who proposed the initial idea for the funded material and a second individual appointed by the journal) as standard procedure for all funded materials. This enables editorial decisions to be easily deputized as should be the case when one editor is an author or is acknowledged as a contributor to a particular article, or when one editor is presented with papers where their own interests may impair their ability to make an unbiased editorial decision. A short statement explaining the process used to make editorial decisions should be included.

Journals should not permit funding organizations to make decisions beyond those about which publications they choose to fund and the extent of the funding. Decisions about the selection of authors and about the selection and editing of contents to be presented in funded publications should be made by the editor (or co-editors) of the funded publication.

Blackwell Publishing reserves the right not to publish any funded publication that does not comply with the requirements defined for the journal to which the manuscript or supplement has been submitted.

Accuracy

Journal editors have a responsibility to ensure the accuracy of the material they publish.

Journals should encourage authors and readers to inform them if they discover errors in published work.

Editors should publish corrections if errors are discovered that could affect the interpretation of data or information presented in an article.

Corrections arising from errors within an article (by authors or journals) should be distinguishable from retractions and statements of concern relating to misconduct (see ‘Informing readers about research and publication misconduct’, p. 5).

Corrections should be included in indexing systems and linked to the original article wherever possible.

See Box 9.

Academic debate

Journals should encourage academic debate.

Journals should encourage correspondence commenting on published items and should always invite authors to respond to any correspondence before publication. However, authors do not have a right to veto unfavorable comments about their work and they may choose not to respond to criticisms.

Neither peer-reviewer comments nor published correspondence should contain personal attacks on the authors. Editors should encourage peer reviewers to criticize the work not the researcher and should edit (or reject) letters containing personal or offensive statements.

Responsible publication practices

Editors should pursue cases of suspected misconduct that become apparent during the peer-review and publication processes, to the extent and in the ways defined in this document in the ‘Promoting research integrity’ section (p. 4). Editors should first work with the authors, the journal owners and/or the journal publishers (at Blackwell Publishing this is via the Journal Publishing Manager), referring to information from the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE), the Council of Science Editors (CSE), or another appropriate body if further advice is needed.

In instances of confirmed misconduct, editors may consider imposing sanctions on the authors at fault for a period of time. Sanctions must be applied consistently. Before imposing sanctions, editors should formally define the conditions in which they will apply (and remove) sanctions, and the processes they will use to do this. Editors of Blackwell journals are encouraged to consult Blackwell Publishing if considering sanctions to ensure that the appropriate processes are applied.

A body such as the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) can provide editors with impartial advice from other editors about difficult cases, provide information about the prevalence of various types of misconduct and other ethical issues, and allow editors to learn from other journals’ experiences by reference to previous cases.

Read more: reported cases of publication misconduct and advice from COPE (15).

Journals should promote responsible publication practices in their instructions for authors.

Read more: Committee on Publication Ethics guidelines on publication practice (5); International Committee of Medical Journal Editors Uniform Requirements (1); Council of Science Editors (CSE) white paper (14); World Association of Medical Editors policy statements (16); Good Publication Practice for pharmaceutical companies (17); American Medical Writers Association Code of Ethics (18); European Medical Writers Association (EMWA) guidelines on the role of medical writers in the development of peer-reviewed publications (19); American Statistical Association (ASA) Comprehensive Ethical Guidelines for Statistical Practice (20); American Chemical Society (ACS) Ethical Guidelines (21); American Psychological Association Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct, Section 8 ‘Research and Publication’ (22); Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) (23); Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy (STARD) (24).

Blackwell Publishing has published general advice on misconduct and the available sanctions (including plagiarism, dealing with research misconduct, and irregularities within the content of an article, including dual publication, libel, slander and obscenity).

Read Blackwell Publishing Copyright FAQs, particularly sections 1.21 [plagiarism (25)], 1.23 [dual publication (2)], 1.24 [libel, slander and obscenity (26)].

See Flowchart 5 (p. 22) ‘What to do if you suspect an ethical problem with a submitted manuscript’ from Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE).

Ownership of ideas and expression

Plagiarism and copyright

Journal editors and readers have a right to expect that submitted work is the author's own, that it has not been plagiarized (i.e. taken from other authors without permission, if permission is required) and that copyright has not been breached (for example, if figures or tables are reproduced).

Many journals require authors to declare that the work reported is their own and that they are the copyright owner (or else have obtained the copyright owner's permission). This is enforced further by the Blackwell Publishing Exclusive License Form, the OnlineOpen Form, or the Copyright Assignment form, one of which must be submitted before publication in any Blackwell journal. This form requires signature from the corresponding author to warrant that the article is an original work, has not been published before and is not being considered for publication elsewhere in its final form either in printed or electronic form.

See ‘Transparency’ (p. 1) and ‘Promoting research integrity’ (p. 4).

Protecting intellectual property

Journal owners and authors have a right to protect their intellectual property.

Different systems are available to protect intellectual property and journals must choose whichever best suits their purpose and ethos. Some Blackwell journals require authors to relinquish their copyright, other Blackwell journals license content from authors, whereas others adopt an open-access model under creative commons licenses. Blackwell Publishing recommends adoption of a system that licenses content from authors, rather than more traditional systems that require copyright assignment/transfer by authors.

- See Box 15.

Box 15. Best Practice: Protecting intellectual property

Blackwell Publishing is legally required to have explicit authority to publish any article. The societies we partner with decide which copyright arrangement they require from the options we provide, a brief and abridged description of which is provided in the bullets below. Blackwell Publishing recommends the Exclusive License Form (ELF) system (for a sample form visit http://www.blackwellpublishing.com/pdf/IJCP_ELF.pdf).- The Blackwell Publishing Exclusive License Form (ELF). This form of copyright agreement, among other things, enables the owners of intellectual property (be they authors or named organisations) to retain copyright in their journal articles; Blackwell Publishing or the journal owner retains the commercial publishing and journal compilation rights.

- The Blackwell Publishing OnlineOpen Exclusive License Form (OOF). While allowing articles to be published and made freely available for all to access online, this form of copyright agreement (among other things and like the ELF) enables the owners of intellectual property (be they authors or named organizations) to retain copyright in their journal articles; the OOF adheres to Creative Commons 2.5 and Blackwell Publishing or the journal owner retains the commercial publishing and journal compilation rights.

- The Copyright Assignment Form (CAF) is also still in use.

Read more: Blackwell Publishing Copyright FAQs (27).

Peer reviewer conduct and intellectual property

Authors are entitled to expect that peer reviewers or other individuals privy to the work an author submits to a journal will not steal their research ideas or plagiarize their work.

Journal guidelines to peer reviewers should be explicit about the roles and responsibilities of peer reviewers, in particular the need to treat submitted material in confidence until it has been published.

Journals should ask peer reviewers to destroy submitted manuscripts after they have reviewed them.

Editors should expect allegations of theft or plagiarism to be substantiated, and should treat allegations of theft or plagiarism seriously.

Editors should protect peer reviewers from authors and, even if peer reviewer identities are revealed, should discourage authors from contacting peer reviewers directly, especially if misconduct is suspected.

See ‘Promoting research integrity’, p. 4.

Read more: Ethics of Peer Review: A Guide for Manuscript Reviewers, from the US Office of Research Integrity (ORI) by Yale University (11).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Committee on Publication Ethics for the use of its flowcharts, and the panel of 25 reviewers who reviewed this document during its development. Lise Baltzer (Blackwell Publishing Asia), Caroline Black (Blackwell Publishing Ltd) and Allen Stevens (Blackwell Publishing Ltd) provided advice and input during development of these guidelines.

Appendix. Flowcharts

Flowchart 1a from Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE)

Flowchart 1b and c from Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE)

Flowchart 1d from Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE)

Flowchart 2a from Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE)

Flowchart 2b from Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE)

Flowchart 3a from Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE)

Flowchart 3b from Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE)

Flowchart 4a from Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE)

Flowchart 4b from Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE)

Flowchart 5 from Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE)

Flowchart 6 from Blackwell Publishing

Flowchart 7 from Blackwell Publishing

Flowchart 8 from Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE)

Flowchart 9 from Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE)

References

- 1.International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Uniform Requirements for Manuscripts Submitted to Biomedical Journals: Writing and Editing for Biomedical Publication. 2006. http://www.ICMJE.org (accessed 23 October.

- 2.Blackwell Publishing. Copyright FAQs Section 1.23 ‘What is the Situation Regarding Dual Publication?’. 2006. http://www.blackwellpublishing.com/bauthor/faqs_copyright.asp#1.23 (accessed 23 October)

- 3.World Health Organization. The World Health Organization Announces New Standards for Registration of All Human Medical Research. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2006/pr25/en/index.html (accessed 23 October 2006)

- 4.Office of Research Integrity. Managing Allegations of Scientific Misconduct: A Guidance Document for Editors. http://ori.dhhs.gov/documents/masm_2000.pdf (accessed 23 October 2006) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Committee on Publication Ethics. Guidelines on Good Publication and Code of Conduct. http://www.publicationethics.org.uk/guidelines (accessed 23 October 2006)

- 6.UK Panel for Research Integrity in Health and Biomedical Sciences. http://www.ukrio.org.uk/home/index.cfm (accessed 23 October 2006)

- 7.World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. http://www.wma.net/e/policy/b3.htm (accessed 23 October 2006) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.US Food and Drug Administration. Good Clinical Practice in FDA-regulated Clinical Trials. http://www.fda.gov/oc/gcp/default.htm (accessed 23 October 2006)

- 9.Medicines Research Council. Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice in Clinical Trials. 2006. http://www.mrc.ac.uk/Utilities/Documentrecord/index.htm?d=MRC002416 (accessed 24 October.

- 10.Blackwell Publishing. Copyright FAQs Section 1.22 ‘What is the Situation Regarding Retractions?’. http://www.blackwellpublishing.com/bauthor/faqs_copyright.asp#1.22 (accessed 23 October 2006)

- 11.Office of Research Integrity/Yale University. Ethics of Peer Review: A Guide for Manuscript Reviewers. http://ori.hhs.gov/education/products/yale/ (accessed 23 October 2006)

- 12.Horton R. Conflicts of interest in clinical research: opprobrium or obsession? Lancet. 1997;349:1112–3. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)22016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith R. Conflict of interest and the BMJ. BMJ. 1994;308:4–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6920.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Council of Science Editors. White Paper on Promoting Integrity in Scientific Journal Publications. http://www.councilscienceeditors.org/editorial_policies/whitepaper/2-5_relations.cfm (accessed 24 October 2006)

- 15.Committee on Publication Ethics. Cases. http://www.publicationethics.org.uk/cases (accessed 24 October 2006)

- 16.World Association of Medical Editors. WAME Policy Statements. http://www.wame.org/wamestmt.htm (accessed 24 October 2006)

- 17.Good Publication Practice for Pharmaceutical Companies. http://www.gpp-guidelines.org/ (accessed 24 October 2006.

- 18.American Medical Writers Association. Code of Ethics. http://www.amwa.org/default.asp?Mode=DirectoryDisplay223 (accessed 24 October 2006)

- 19.European Medical Writers Association Guidelines on the Role of Medical Writers in the Development of Peer-reviewed Publications. http://www.emwa.org/Mum/EMWAguidelines.pdf (accessed 24 October 2006)

- 20.American Statistical Association. Ethical Guidelines for Statistical Practice. http://www.amstat.org/profession/index.cfm?fuseaction=ethicalstatistics (accessed 24 October 2006)

- 21.American Chemical Society. Ethical Guidelines. http://pubs.acs.org/instruct/ethic.html (accessed 24 October 2006)

- 22.American Psychological Association. Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct, Section 8 ‘Research and Publication’. http://www.apa.org/ethics/code2002.html#8 (accessed 24 October 2006)

- 23.Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) http://www.consort-statement.org/ (accessed 24 October 2006)

- 24.Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy (STARD) http://www.consort-statement.org/stardstatement.htm (accessed 24 October 2006) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Blackwell Publishing. Copyright FAQs, Section 1.21 ‘What is the Situation Regarding Plagiarism?’. http://www.blackwellpublishing.com/bauthor/faqs_copyright.asp#1.23 (accessed 24 October 2006)

- 26.Blackwell Publishing. Copyright FAQs, Section 1.24 ‘Can You Provide Advice Regarding Libel, Slander and Obscenity?’. http://www.blackwellpublishing.com/bauthor/faqs_copyright.asp#1.23 (accessed 24 October 2006)

- 27.Blackwell Publishing. Copyright FAQs. http://www.blackwellpublishing.com/bauthor/faq_main.asp (accessed 17 November 2006)