Abstract

Acid pH often triggers changes in gene expression. However, little is known about the identity of the gene products that sense fluctuations in extracytoplasmic pH. The Gram-negative pathogen Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium experiences a number of acidic environments both inside and outside animal hosts. Growth in mild acid (pH 5.8) promotes transcription of genes activated by the response regulator PmrA, but the signalling pathway(s) that mediates this response has thus far remained unexplored. Here we report that this activation requires both PmrA's cognate sensor kinase PmrB, which had been previously shown to respond to Fe3+ and Al3+, and PmrA's post-translational activator PmrD. Substitution of a conserved histidine or of either one of four conserved glutamic acid residues in the periplasmic domain of PmrB severely decreased or abolished the mild acid-promoted transcription of PmrA-activated genes. The PmrA/PmrB system controls lipopolysaccharide modifications mediating resistance to the antibiotic polymyxin B. Wild-type Salmonella grown at pH 5.8 were > 100 000-fold more resistant to polymyxin B than organisms grown at pH 7.7. Our results suggest that protonation of the PmrB periplasmic histidine and/or of the glutamic acid residues activate the PmrA protein, and that mild acid promotes cellular changes resulting in polymyxin B resistance.

Introduction

Free-living organisms often encounter wide variations in the pH of their surroundings. Thus, pH may act as a signal that triggers cellular responses designed to cope with a new environment. The Gram-negative bacterium Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, for example, experiences a number of acidic environments both inside and outside animal hosts. During infection of a mammalian host, Salmonella is exposed to severe acidity in the stomach (Rychlik and Barrow, 2005) and mild acidification in the endocytic vacuoles of intestinal epithelia and macrophages (Brumell and Grinstein, 2004). Moreover, Salmonella has been recovered from soil and water (Winfield and Groisman, 2003) where the pH can be significantly low. While growth in acidic conditions has been shown to promote changes in the gene expression profiles of several bacterial species (Tucker et al., 2002; McGowan et al., 2003; Weinrick et al., 2004; Leaphart et al., 2006), less is known about the identity of the molecule(s) that sense extracytoplasmic fluctuations in pH and the mechanisms by which such sensors promote changes in gene expression.

Previous studies have revealed that Salmonella responds to acidic challenges through an adaptive system called the acid tolerance response in which adaptation to mild acid conditions enables the organism to survive periods of severe acid stress (Foster and Hall, 1990; Foster, 1995). The acid tolerance response of Salmonella results in the synthesis of over 50 acid shock proteins (Bearson et al., 1998) that are likely to function primarily when variations in internal pH occur, i.e. when Salmonella experiences severe acidic conditions (pH ∼3) (Foster, 2004).

Growth of Salmonella in mild acid (pH 5.8) also promotes transcription of genes regulated by the response regulator PmrA (Soncini and Groisman, 1996). The expression of these genes has been shown to be dispensable for the acid tolerance response (Bearson et al., 1998) which suggests that there are still uncharacterized cellular function(s) that Salmonella needs to regulate in acidic environments. The PmrA protein and its cognate sensor kinase PmrB form a two-component regulatory system that is required for virulence in mice (Gunn et al., 2000), infection of chicken macrophages (Zhao et al., 2002), growth in soil (Chamnongpol et al., 2002), resistance to the cationic peptide antibiotic polymyxin B (Roland et al., 1993) and resistance to Fe3+- (Wosten et al., 2000) and Al3+-mediated killing (Nishino et al., 2006). The PmrA-regulated products characterized thus far mediate modifications to the various components of the lipopolysacharide (LPS) structure including the lipid A (Gunn et al., 1998; Trent et al., 2001; Zhou et al., 2001; Breazeale et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2004), the core region (Nishino et al., 2006) and the O-antigen (Delgado et al., 2006). While other PmrA-regulated genes have been identified (Marchal et al., 2004; Tamayo et al., 2005), their biochemical activities and the role(s) that they play in Salmonella's life remain unknown.

Besides mild acid pH, two other stimuli are known to promote expression of PmrA-activated genes: (i) submillimolar levels of extracellular Fe3+ or Al3+, which are directly sensed by the PmrB protein (Wosten et al., 2000), and (ii) low concentrations of extracellular Mg2+ (Soncini and Groisman, 1996) (Fig. 1). The low Mg2+ activation of the PmrA protein requires PhoQ, a protein that senses extracellular Mg2+ levels (Vescovi et al., 1996), PhoQ's cognate regulator PhoP, and the PhoP-activated protein PmrD (Kox et al., 2000; Kato and Groisman, 2004). PmrD binds to the phosphorylated form of PmrA protecting it from dephosphorylation by PmrB (Kato and Groisman, 2004). Here we show that PmrA's cognate sensor kinase PmrB is required for responding to external changes in pH through a mechanism that requires a histidine and several glutamic acid residues located in its periplasmic domain, as well as the post-translational activator PmrD protein.

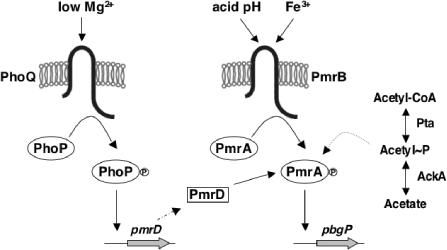

Fig. 1.

Model depicting the pathways leading to activation of the PmrA protein. Fe3+ and acid pH are sensed by the PmrB protein, which promotes phosphorylation of PmrA, resulting in transcription of PmrA-activated genes. The PhoQ protein senses extracellular Mg2+. In low Mg2+, PhoQ promotes phosphorylation of PhoP and transcription of pmrD. The PmrD protein binds to the phosphorylated form of PmrA protecting it from dephosphorylation by PmrB. Acetyl phosphate, which is synthesized by the enzymes phosphotransacetylase (Pta) and acetate kinase (AckA), activates PmrA in a strain deleted for the pmrB gene.

Results

Mild acid pH induces transcription of PmrA-regulated genes

To examine the mild acid pH induction of PmrA-activated genes, we grew Salmonella cells harbouring chromosomal lacZYA transcriptional fusions to the PmrA-regulated genes pbgP, pmrC and ugd (Wosten and Groisman, 1999) in N-minimal media buffered at pH 5.8 or 7.7. This medium lacked Fe3+ or Al3+, the only known PmrB ligands (Wosten et al., 2000), and contained 10 mM MgCl2, which represses expression of PmrA-activated genes (Soncini and Groisman, 1996; Kox et al., 2000). All three genes were expressed when cells were grown in media buffered at pH 5.8 but not at pH 7.7 (Fig. 2A–C), in agreement with previous results (Soncini and Groisman, 1996). A similar induction of pbgP transcription was found when MES was used as the buffering agent in the media at pH 5.8 instead of Bis-Tris (data not shown), indicating that the mild acid effect on gene expression was not due to a particular buffering system.

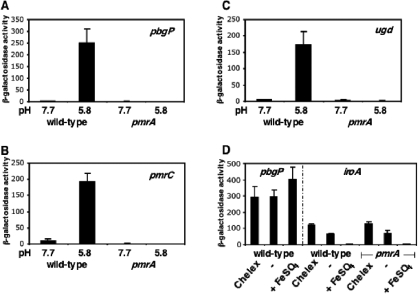

Fig. 2.

Mild acid pH promotes transcription of PmrA-regulated genes. A–C. β-Galactosidase activity (Miller units) expressed by strains harbouring chromosomal lac transcriptional fusions to the PmrA-activated pbgP (EG9241, EG9681) (A), pmrC (EG9279, EG9687) (B) and ugd (EG9524, EG9674) (C) genes. Strain numbers are indicated in parenthesis, with the first one corresponding to the pmrA+ and the second to the pmrA background. Expression was investigated in wild-type and pmrA backgrounds following growth in N-minimal medium pH 7.7 or 5.8 as described under Experimental procedures. Shown are the mean values and standard deviations of three independent experiments performed in duplicate. D. β-Galactosidase activity (Miller units) expressed by strains harbouring chromosomal lac transcriptional fusions to the PmrA-activated pbgP (EG9241) and iron-repressed iroA (EG12735, EG12737) genes. Cells were grown in Chelex-treated or untreated N-minimal medium pH 5.8. FeSO4 (100 μM) was added to the Chelex-treated medium where indicated. Shown are the mean values and standard deviations of three independent experiments performed in duplicate.

The transcriptional activation of PmrA-regulated genes taking place at pH 5.8 could be due to trace amounts of metals such as Fe3+, which is more soluble at acidic pH. To rule out this possibility, we treated the culture medium with Chelex 100 resin, an agent known to chelate polyvalent metal ions that does not affect Salmonella growth. We determined that Chelex 100 was effective at chelating iron because expression of the pmrA-independent iron-repressed iroA gene (Hall and Foster, 1996) was induced to higher levels in cultures treated with Chelex 100 (Fig. 2D). Expression of pbgP was still induced when Salmonella was grown in the Chelex-treated medium (Fig. 2D) or in media containing the specific Fe3+ chelator deferoxamine mesylate (data not shown) supporting the notion that mild acid pH is responsible for the observed induction.

We determined that the regulatory protein PmrA is required for the transcriptional activation in response to mild acid pH because there was no induction of the three investigated genes in a pmrA mutant (Fig. 2A–C). Moreover, a mutant expressing a derivative of the PmrA protein that cannot be phosphorylated due to substitution of the putative phosphorylation residue aspartate 51 by alanine (Kato and Groisman, 2004) completely failed to promote transcription of PmrA-activated genes in response to pH 5.8, in a similar fashion to the pmrA strain (A. Kato and E.A. Groisman, unpubl. results). From these results we conclude that Salmonella harbours a signalling pathway that responds to mild acid pH by activating the PmrA protein through phosphorylation.

The PmrB protein is necessary for the mild acid activation of PmrA

The PmrB protein is necessary for activation of the PmrA protein in low Mg2+ (Kox et al., 2000; Kato and Groisman, 2004) and in the presence of Fe3+ (Wosten et al., 2000), consistent with the notion that PmrB is the major phosphodonor for PmrA. We investigated whether PmrB was also required for the pH-dependent induction of pbgP, which was chosen as a prototypical PmrA-activated gene because the PmrA protein binds to the pbgP promoter in vitro (Wosten and Groisman, 1999) and in vivo (Shin and Groisman, 2005). Thus, we determined the β-galactosidase activity of isogenic pmrB strains harbouring a chromosomal pbgP–lac transcriptional fusion: expression was approximately sixfold lower in a pmrB mutant than in the pmrB+ strain following growth at pH 5.8 (Fig. 3), indicating that a functional pmrB gene is necessary for a normal response to mild acid pH.

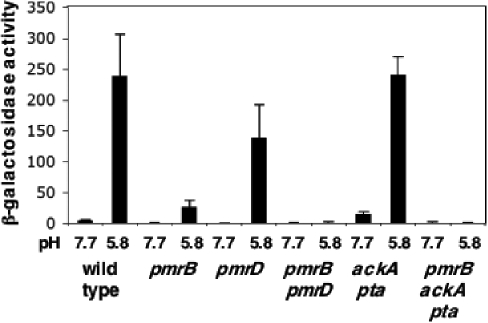

Fig. 3.

The PmrA-cognate sensor PmrB is required to activate the PmrA-regulated gene pbgP in response to mild acid pH. β-Galactosidase activity (Miller units) expressed by strains harbouring a chromosomal lac transcriptional fusion to the pbgP gene. Expression was investigated in wild-type (EG9241), pmrB (EG16704) and pmrD (EG11775) mutant, pmrB pmrD (EG12060) and ackA pta (EG16450) double mutant and the pmrB ackA pta triple mutant (EG16706) backgrounds. Cells were grown in N-minimal medium pH 7.7 or 5.8 as described under Experimental procedures. Shown are the mean values and standard deviations of three independent experiments performed in duplicate.

There was residual pbgP expression in the pmrB mutant induced with mild acid pH (Fig. 3), which was in contrast to the absence of pbgP transcription in the pmrA mutant (Fig. 2). This suggested that PmrA could become phosphorylated from another phosphodonor(s) when PmrB is not present. We considered the possibility of PmrA being phosphorylated from acetyl phosphate because acetyl phosphate has been shown to serve as phosphoryl donor to several response regulators when their cognate sensors are absent (see Wolfe, 2005 for a review). Consistent with this notion, pbgP transcription was abrogated in the pmrB mutant upon deletion of the pta and ackA genes (Fig. 3), which encode the two enzymes that are required for the production of acetyl phosphate (Wolfe, 2005) (Fig. 1). In contrast, a strain lacking the ability to synthesize acetyl phosphate but with a functional pmrB gene exhibited wild-type pbgP expression levels (Fig. 3), implying that under normal conditions (i.e. when a functional pmrB gene is present) acetyl phosphate does not contribute to PmrA phosphorylation.

The PmrD protein is necessary for normal PmrA activation at pH 5.8

The PhoP-activated PmrD protein favours the phosphorylated state of the PmrA protein (Fig. 1) (Kato and Groisman, 2004). Thus, we tested the possibility of PmrD participating in the PmrA-dependent response to acidic conditions, and thus contributing to the pbgP transcription remaining in a pmrB mutant. Expression of the pbgP gene was abolished in a pmrB pmrD double mutant (Fig. 3) indicating that both genes are necessary to activate PmrA under acidic conditions. In contrast to the phenotype of the pta ackA double mutant, pbgP transcription was reduced in the pmrD mutant (Fig. 3). These results imply that the pmrD gene was being expressed even though the media contained 10 mM MgCl2, a concentration known to repress transcription of PhoP-activated genes (Soncini et al., 1996).

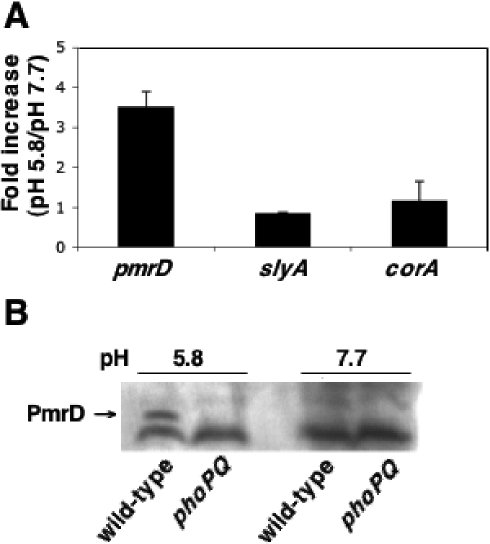

We examined transcription of the pmrD gene using RNA isolated from organisms grown at pH 5.8 or 7.7. Growth at pH 5.8 resulted in pmrD transcript levels that were ∼3.5-fold higher than in organisms grown at pH 7.7 (Fig. 4A). This acid pH-promoted increase appears to be specific to a subset of PhoP-activated genes (our unpublished results) that includes pmrD because expression of the PhoP-regulated slyA gene and the PhoP-independent corA gene was not affected by the pH of the medium (Fig. 4A). In agreement with the gene transcription data, Western blot analysis of crude extracts using anti-PmrD antibodies showed that the PmrD protein was produced in cells grown in N-minimal medium pH 5.8 and 10 mM MgCl2 but not in cells grown in the same medium buffered at pH 7.7 (Fig. 4B). The acid-promoted expression of the PmrD protein was phoPQ-dependent, which is in agreement with the fact that PhoP is the only known direct transcriptional activator of pmrD (Kox et al., 2000).

Fig. 4.

Expression of the pmrD gene is promoted under mild acid pH. A. RNA levels of transcripts corresponding to the PhoP-activated pmrD and slyA genes and to the PhoP-independent corA gene as determined by quantitative real-time PCR. Shown are the mean values and standard deviations of three independent experiments. B. Western blot analysis of crude bacterial extracts prepared from wild-type (14028s) or phoPQ (EG15598) cells grown in N-minimal medium at pH 5.8 or 7.7 as described under Experimental procedures. The upper band corresponds to PmrD. The lower band is a non-specific cross-reactive product that indicates equal protein loading across the lanes.

Conserved histidine and glutamic acid residues in the periplasmic domain of PmrB are required for signalling in response to mild acid pH

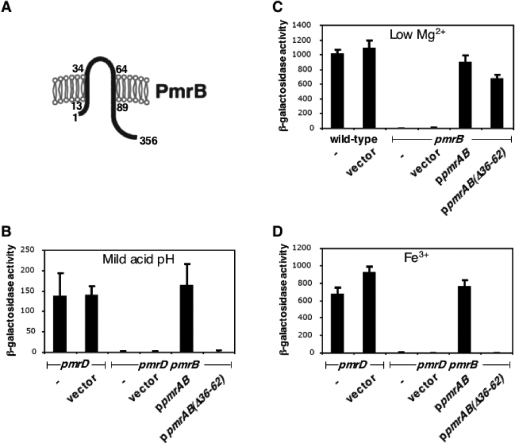

The results described above established that PmrB is required for activation of PmrA in response to mild acid pH. This could be because PmrB is directly involved in sensing extracytoplasmic pH in a way analogous to its sensing of Fe3+ and Al3+ (Wosten et al., 2000), or because PmrB plays an indirect role in its capacity of main (if not sole) phosphodonor for PmrA. In fact, PmrB is required for the activation of PmrA-regulated genes in response to the low Mg2+ signal, which is sensed by the PhoQ protein (Kato and Groisman, 2004) (Fig. 1). Thus, we reasoned that if PmrB senses extracytoplasmic pH directly, its periplasmic domain (Fig. 5A) was likely to be required for the response to this signal. To examine this hypothesis, we tested a Salmonella strain with a chromosomal pbgP–lac fusion, deleted for the chromosomal copy of the pmrB gene and harbouring a plasmid expressing a PmrB protein lacking its periplasmic domain for its ability to promote pbgP expression in response to different signals. There was no pbgP expression in cells grown at pH 5.8 (Fig. 5B) or in the presence of Fe3+ (Fig. 5D), which is in contrast to the normal activation in response to low Mg2+ (Fig. 5C). Together, these results argue in favour of the notion that PmrB senses extracellular pH besides its previously described ligands Fe3+ and Al3+ (Wosten et al., 2000).

Fig. 5.

The periplasmic domain of the PmrB protein is required for responding to mild acid pH. A. Predicted topology of the sensor kinase PmrB in the inner membrane. Numbers indicate amino acid positions. B–D. β-Galactosidase activity (Miller units) expressed by wild type (EG9241), pmrB (EG10065) and pmrD pmrB (EG12060) mutant strains harbouring a lac transcriptional fusion to pbgP and either the plasmid vector pUHE21lacIq, plasmid ppmrAB expressing the wild-type pmrAB genes or plasmid ppmrAB(Δ36-62) expressing the wild-type PmrA protein and a PmrB protein deleted for 26 of its 31 periplasmic domain residues. Cells were grown in N-minimal medium containing 10 mM MgCl2, pH 5.8 (B), 10 μM MgCl2, pH 7.7 (C) or 10 μM MgCl2, 100 μM FeSO4, pH 7.7 (D). The β-galactosidase activity in all strains grown under non-inducing conditions, i.e. N-minimal medium containing 10 mM MgCl2, pH 7.7, was undetectable. Shown are the mean values and standard deviations of three independent experiments performed in duplicate.

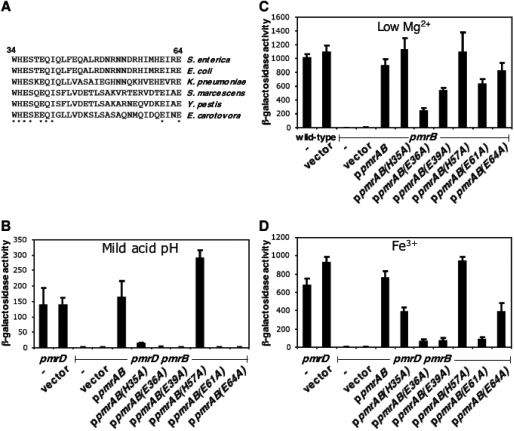

An alignment of the amino acid sequences corresponding to the putative periplasmic domain of the PmrB proteins from six enteric species revealed that nine residues are highly conserved (Fig. 6A). Interestingly, one of these conserved residues was a histidine at position 35. Because the pKa of free histidine is ∼6, the pH at which PmrA-activated genes are induced, we hypothesized that this residue might be required for pH sensing. To test this hypothesis, we constructed a plasmid that produced a PmrB protein containing a single histidine to alanine substitution at position 35. While this mutation severely diminished the ability of Salmonella to respond to mild acid pH, there still was some residual pbgP expression (Fig. 6B) suggesting that other residues might also be required for pH sensing. We considered the possibility that a second histidine at position 57 could be involved in sensing acid despite the fact that this residue was only partially conserved across species (Fig. 6A). However, the substitution of this residue by alanine had no effect on the response to mild acid pH (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

Conserved histidine and glutamic acid residues in the periplasmic domain of the PmrB protein are required for PmrA-mediated transcription in response to mild acid pH. A. Alignment of the amino acid sequences corresponding to the putative periplasmic domains of the PmrB proteins from Salmonella enterica, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Serratia marcescens, Yersinia pestis and Erwinia carotovora. Asterisks (*) denote residues conserved in all six species. B–D. β-Galactosidase activity (Miller units) expressed by wild-type (EG9241), pmrB (EG10065) and pmrD pmrB (EG12060) mutant strains harbouring a lac transcriptional fusion to pbgP and plasmid vector pUHE21lacIq, plasmid ppmrAB expressing the wild-type pmrAB genes, or plasmids in which the nucleotide sequence corresponding to periplasmic histidines and glutamates were mutated to alanine [ppmrAB(H35A), ppmrAB(E36A), ppmrAB(E39A), ppmrAB(H57A), ppmrAB(E61A), ppmrAB(E64A)]. Cells were grown in N-minimal medium containing 10 mM MgCl2, pH 5.8 (B), 10 μM MgCl2, pH 7.7 (C) or 10 μM MgCl2, 100 μM FeSO4, pH 7.7 (D). The β-galactosidase activity in all strains grown under non-inducing conditions, i.e. N-minimal medium containing 10 mM MgCl2, pH 7.7, was undetectable. Shown are the mean values and standard deviations of three independent experiments performed in duplicate.

Four of the nine conserved amino acids in the periplasmic domain of PmrB are glutamic acid residues, which also could be subjected to changes in protonation upon variations in the pH of their surroundings. Although the pKa of free glutamic acid is ∼4, which is well below the range of pH at which PmrA-activated genes are induced, the folding of a protein can dramatically change the pKa of its residues. For instance, the pKa of one of the glutamic acid residues of the regulatory protein TraM is ∼7.7 (Lu et al., 2006). Therefore, we hypothesized that one or more of the glutamates might be required for pH sensing. To test this hypothesis, we used plasmids that produced PmrB proteins containing single-amino-acid replacements in the conserved glutamic acid residues. When either one of the four conserved glutamates was substituted by alanine Salmonella could no longer respond to mild acid pH (Fig. 6B). Strains expressing the mutant PmrB proteins could express pbgP normally in response to the low Mg2+ signal (Fig. 6C) (Wosten et al., 2000), indicating that mutations in residues of the periplasmic domain of PmrB do not impair the enzymatic activity of the cytoplasmic domain of the PmrB protein. These results indicate that the periplasmic glutamates are required for responding to mild acid pH.

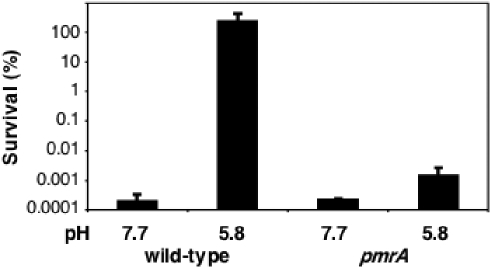

Mild acid pH induces resistance to the antimicrobial peptide polymyxin B

What role could the mild acid pH-dependent activation of PmrA-regulated genes play in Salmonella's lifestyle? Because the PmrA/PmrB system is required for resistance to the antimicrobial peptide polymyxin B (Roland et al., 1993), we hypothesized that mild acid pH could induce this resistance. In fact, the survival of wild-type cells to a challenge with polymyxin B was 100 000-fold higher when they were grown at pH 5.8 than when grown at pH 7.7 (Fig. 7). This resistance was PmrA-dependent because a strain deficient in the pmrA gene was approximately 100 000-fold more sensitive to polymyxin B than the wild-type strain when grown pH 5.8 (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Mild acid pH induces resistance to the antimicrobial peptide polymyxin B. Per cent survival of wild-type (14028s) and pmrA (EG7139) strains after incubation with polymyxin B (1.5 μg ml−1). Cells were grown in N-minimal medium, pH 7.7 or 5.8, containing 10 mM MgCl2, before incubation with polymyxin B. Shown are the mean values and standard deviations of three independent experiments performed in duplicate.

Discussion

We have established that the sensor kinase PmrB is the primary sensor that activates the PmrA protein when Salmonella experiences mild acid pH, resulting in transcription of PmrA-activated genes (Fig. 1). That PmrB is likely to sense changes in pH directly is supported by three findings: (i) the mild acid pH-dependent activation of the PmrA-regulated gene pbgP was dramatically reduced in a strain lacking pmrB (Fig. 3), (ii) the periplasmic domain of PmrB was necessary for activation of pbgP under mild acid conditions (Fig. 5), and (iii) single amino acid substitutions in conserved histidine and glutamic acid residues located in the periplasmic domain of PmrB abolished its ability to stimulate pbgP transcription at pH 5.8 (Fig. 6). The periplasmic histidine and glutamates are conserved in the PmrB periplasmic domain of other enteric species, raising the possibility that the signalling pathway described in this article may be operating in other organisms in addition to S. enterica.

The requirement of periplasmic PmrB residues in the mild acid pH activation of PmrA-regulated genes suggests that this signalling pathway responds to changes in extracytoplasmic pH. Moreover, under the experimental conditions used in this study it is unlikely that the cytoplasmic pH varied significantly because: first, bacterial cells can maintain an internal pH of up to 2 units higher than the external pH (Foster, 2004); in fact, Slonczewski et al. (1981) determined that the intracellular pH in Escherichia coli cells was 7.4 even when the external pH was 5.5. Second, acid stress can become a severe challenge for bacterial cells when organic acids such as acetate or products of fermentation are present in the medium (Bearson et al., 1998); and in our experiments we used a non-fermentable sugar (glycerol) and inorganic acids which are not expected to cause such acid stress.

Structural changes driven by a relatively narrow variation in pH (1–2 units) have been reported for several cytosolic bacterial proteins (Tews et al., 2005; Lu et al., 2006). This is in contrast to the few membrane proteins (other than ion channels) that have been shown to respond to changes in extracellular pH of a similar magnitude. For example, the eukaryotic G-protein coupled receptor OGR1 is inactive at pH 7.8 and fully active at pH 6.8 suggesting that the pH sensing mechanism involves protonation of several extracytoplasmic histidines (Ludwig et al., 2003), which is in agreement with the pKa of free histidine of ∼6. In the case of PmrB, a normal response to mild acid pH requires not only a periplasmic histidine but also several glutamic acid residues. Therefore, regulation of PmrB activity may involve protonation of one or more of these amino acids. Even though protonation of the glutamic acid residues may seem unlikely given the fact that the pKa of free glutamic acid is ∼4, protein folding can change the pKa of its residues (Tanford and Roxby, 1972). Indeed, the pKa of one of the glutamic acid residues of the regulatory protein TraM is ∼7.7 in the folded protein (Lu et al., 2006). Therefore, it is plausible that protonation/deprotonation of one or more of the glutamic acids in the periplasmic domain of PmrB could occur at pH ∼5.8.

Integral membrane proteins that recognize signals in addition to extracytoplasmic pH, such as PmrB, have been identified both in prokaryotes and in eukaryotes. The CadC protein of E. coli, for example, is activated by exogenous lysine besides acid pH (Dell et al., 1994). Likewise, the human receptor OGR1 responds to both pH and sphingosylphosphorylcholine (Ludwig et al., 2003). The fact that the PmrB H35A and the E64A mutant proteins displayed partial activity in response to ferric iron but were severely impaired in their ability to respond to acid pH (compare Fig. 6B and D) supports the notion that these signals are sensed independently. Similarly, cadC mutants have been isolated that are impaired in the ability to sense only one of its two inducing signals (Dell et al., 1994). Furthermore, the ability to sense two different compounds has also recently been shown to be genetically distinguishable in the bacterial chemoreceptor Tcp (Iwama et al., 2006).

The PmrB protein plays the primary role in the pH-dependent activation of PmrA, but full activation also requires PmrD, the post-translational activator of the PmrA protein (Fig. 3). The levels of phosphorylated PmrA are determined by the balance of the autokinase + phosphotransferase activity of PmrB and PmrB's phosphatase activity towards phospho-PmrA. Thus, PmrD may be necessary to ensure that the amount of phosphorylated PmrA is such to promote transcription of its regulated genes. Consistent with its role in acid pH activation, expression of the pmrD gene was promoted in media of mild acid pH (Fig. 4). The mechanism(s) by which acid pH leads to an increase in the levels of the pmrD transcript, however, remains unclear. Although it has been suggested that the Salmonella PhoQ protein senses acid pH (Aranda et al., 1992) or responds to both pH and Mg2+ (Bearson et al., 1998), a direct role for PhoQ in responding to acid pH appears unlikely because not all PhoP-regulated genes are activated under these conditions, which is in contrast to low Mg2+ activating the whole PhoP regulon (see Groisman and Mouslim, 2006 for a review).

What role could the pH-dependent activation of PmrA-regulated genes play in Salmonella's lifestyle? Because several PmrA-activated gene products are responsible for remodelling the LPS structure and these modifications are required for resistance to certain antimicrobial peptides and toxic metals, one possibility is that acidic environments provide a means to induce the cell envelope changes resulting in resistance. Indeed, when grown at pH 5.8 wild-type Salmonella were 100 000-fold more resistant to polymyxin B than when grown at pH 7.7 (Fig. 7). This may be particularly important for Salmonella living in soil due to the fact that the antimicrobial peptide polymyxin B is produced by the soil bacterium Paenibacillus polymyxa (Paulus and Gray, 1964) and because the solubility of metals such as Fe3+ increases in acid pH. On the other hand, although mild acid (pH 6.0) per se, i.e. even in the presence of high Mg2+, promotes LPS modifications (Gibbons et al., 2005), the low pH signal may also act synergistically with the low Mg2+ signal in vivo because Mg2+ deprivation alone is not sufficient to provide all the LPS modifications seen in Salmonella when present inside macrophages (Gibbons et al., 2005). Finally, while a role for the PmrA-dependent LPS modifications in the previously described acid tolerance response is unlikely because survival to acid stress (pH ∼3) was not reduced in cells deficient in pmrA (data not shown and Bearson et al., 1998), some of the PmrA-regulated genes to which no function has been ascribed yet could mediate other cellular responses to acid pH.

Experimental procedures

Bacterial strains, plasmids and growth conditions

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. All S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strains are derived from wild-type 14028s and were constructed by phage P22-mediated transductions as described elsewhere (Davis et al., 1980). Bacteria were grown at 37°C in N-minimal media (Snavely et al., 1991) buffered in 50 mM Bis-Tris (or MES), pH 7.7 or 5.8, supplemented with 0.1% casamino acids, 38 mM glycerol and 10 μM or 10 mM MgCl2. When indicated, medium was treated overnight with Chelex 100 resin (Sigma) to chelate metal ions before using it for cell culture. Deferoxamine mesylate (Sigma) was used at a final concentration of 300 μM. FeSO4 was used at 100 μM. E. coli DH5α was used as the host for preparation of plasmid DNA. Ampicillin and kanamycin were used at 50 μg ml−1 and chloramphenicol was used at 20 μg ml−1.

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study.

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| S. enterica | ||

| 14028s | Wild type | ATCC |

| EG7139 | pmrA::CmR | Soncini and Groisman (1996) |

| EG9241 | pbgP::MudJ | Soncini et al. (1996) |

| EG9681 | pmrA::CmRpbgP::MudJ | Soncini and Groisman (1996) |

| EG9279 | pmrC::MudJ | Soncini and Groisman (1996) |

| EG9687 | pmrA::CmRpmrC::MudJ | Soncini and Groisman (1996) |

| EG9524 | ugd::MudJ | Vescovi et al. (1996) |

| EG9674 | pmrA::CmRugd::MudJ | Soncini and Groisman (1996) |

| EG12735 | iroA1::MudJ | Hall and Foster (1996) |

| EG12737 | pmrA::CmRiroA1::MudJ | S. Chamnongpol and E.A. Groisman (unpublished) |

| EG10065 | pmrB::CmRpbgP::MudJ | Kox et al. (2000) |

| EG11775 | pmrD::CmRpbgP::MudJ | Kox et al. (2000) |

| EG12060 | pmrB::CmRpmrD::CmRpbgP::MudJ | Kox et al. (2000) |

| EG15598 | ΔphoP/phoQ::CmR | Shin and Groisman (2005) |

| EG16443 | ΔackA/pta::CmR | This work |

| EG16450 | ΔackA/pta::CmRpbgP::MudJ | This work |

| EG16704 | ΔpmrB pbgP::MudJ | This work |

| EG16706 | ΔpmrBΔackA/pta::CmRpbgP::MudJ | This work |

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | F–supE44 ΔlacU169 (φ80 lacZΔM15) hsdR17 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 relA1 | Hanahan (1983) |

| Plasmids | ||

| pUHE21-2lacIq | reppMB1 ApRlacI q | Soncini et al. (1995) |

| pEG9102 | reppMB1 ApRlacI qpmrAB | Soncini and Groisman (1996) |

| pUHpmrAB(Δ36-62) | reppMB1 ApRlacI qpmrAB (Δ36-62) | Wosten et al. (2000) |

| pUHpmrAB(H35A) | reppMB1 ApRlacI qpmrAB (H35A) | This work |

| pUHpmrAB(E36A) | reppMB1 ApRlacI qpmrAB (E36A) | Wosten et al. (2000) |

| pUHpmrAB(E39A) | reppMB1 ApRlacI qpmrAB (E39A) | Wosten et al. (2000) |

| pUHpmrAB(H57A) | reppMB1 ApRlacI qpmrAB (H57A) | This work |

| pUHpmrAB(E61A) | reppMB1 ApRlacI qpmrAB (E61A) | Wosten et al. (2000) |

| pUHpmrAB(E64A) | reppMB1 ApRlacI qpmrAB (E64A) | Wosten et al. (2000) |

| pKD3 | repR6Kγ ApR FRT CmR FRT | Datsenko and Wanner (2000) |

| pKD46 | reppSC101ts ApR paraBADγβ exo | Datsenko and Wanner (2000) |

| pCP20 | reppSC101ts ApR CmRcl857 λPRflp | Cherepanov and Wackernagel (1995) |

Construction of chromosomal gene deletion mutants and plasmids

Strain EG16443, which has a deletion of both the ackA and pta genes, was constructed by the one-step gene inactivation method (Datsenko and Wanner, 2000) as follows: a CmR cassette was amplified using primers 5956 (5′-CTGACGTTTTTTTAGCCACGTATCATAAATAGGTACTTCCGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC-3′) and 5957 (5′-TTACTGCTGCTGCTGAGAAGCCTGGATCGCCGTCAGGGCGCATATGAATATCCTCCTTAG-3′) and pKD3 as template and recombined into the ackA pta region in strain 14028s. The structure of the generated mutant was verified by colony PCR as described elsewhere (Datsenko and Wanner, 2000).

Plasmids pUHpmrAB containing the H35A and H57A substitutions were constructed using the QuickChange II Site-directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene) with primers 7075 (5′-AGTACCTTCTGGTTATGGGCTGAAAGCACTGAGCA-3′) and 7076 (5′-TGCTCAGTGCTTTCAGCCCATAACCAGAAGGTACT-3′); 7077 (5′-AATCGCAACAACGATCGCGCTATCATGCACGAAAT-3′) and 7078 (5′-ATTTCGTGCATGATAGCGCGATCGTTGTTGCGATT-3′) respectively.

β-Galactosidase assays

Cells were grown overnight in N-minimal media, pH 7.7, and washed once in N-minimal media pH 7.7 or 5.8 before inoculation into media of the same pH. Activity was determined as described elsewhere (Miller, 1972) after 4 h of growth at 37°C.

Immunoblotting analysis

Cells were grown in 20 ml of N-minimal media, pH 7.7 or 5.8, to OD600∼0.5, washed with TBS twice, resuspended in 500 μl of TBS and opened by sonication. Whole-cell lysates were run on NuPAGE Bis-Tris gels (Invitrogen) with MES running buffer, transferred to PVDF membranes and analysed by immunoblotting with an anti-PmrD polyclonal antibody. Blots were developed by using anti-rabbit IgG horseradish peroxidase-linked antibodies (Amersham Biosciences) and Supersignal West Femto (Pierce).

RNA isolation, reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) and real-time PCR

Cells were grown in 10 ml of N-minimal media, pH 7.7 or 5.8, to OD600∼0.5. One millilitre of culture was used to prepare total RNA using the SV Total RNA Isolation System (Promega). cDNA was synthesized using TaqMan (Applied Biosystems) and random hexamers following the manufacturer's instructions. Quantification of transcripts was performed by real-time PCR using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) in an ABI 7000 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems). Two different sets of primers were used to detect the pmrD transcript (both gave similar results): 4491 (5′-GGTTAAGAAATCGCATTATGTCAAAA-3′) and 4492 (5′-CGAACCGCCGCTATCG-3′); 6528 (5′-TGGAATGGTTGGTTAAGAAATCG-3′) and 6529 (5′-CATGGCACGCCCTCTTTTT-3′). Primers 6496 (5′-AGCGATAGGCATTGAGCAGC-3′) and 6497 (5′-CAGGTTTGCCGCGAAATTAG-3′) were used to detect the slyA transcript and 6213 (5′-GCTGGAAGTCGAGGAGTCACA-3′) and 6214 (5′-TCGTCCGGTTCGACCAAA-3′) to quantify the corA transcript. Results were normalized to the levels of 16S ribosomal RNA which were estimated using primers 3032 (5′-CCAGCAGCCGCGGTAAT-3′) and 3034 (5′-TTTACGCCCAGTAATTCCGATT-3′). The amount of each PCR product was calculated from standard curves obtained from PCR with the same primers and serially diluted DNA.

Polymyxin B susceptibility assay

Assays were performed following a previously described protocol (Groisman et al., 1992) with a few modifications. Bacteria were grown overnight in N-minimal media, pH 7.7, containing 10 mM MgCl2, and washed once in N-minimal media pH 7.7 or 5.8 before inoculation (1:50 dilution) into 10 ml of media of the same pH. Cells were grown at 37°C with aeration to OD600∼0.6 and diluted 1:100 in LB broth. A 300 μg ml−1 stock solution of water-dissolved polymyxin B was diluted 1:100 in LB broth immediately before the assay. Fifty microlitres of diluted cells and 50 μl of diluted polymyxin B solution were mixed and placed in 96-well plates for 1 h at 37°C with shaking. A portion of each sample was serially diluted and plated on LB agar plates to determine the number of colony-forming units (cfu). Per cent survival was calculated as follows:

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Kato for insightful suggestions, J.W. Foster for critically reading the manuscript and for providing the iroA–lacZ strain, and members of the Groisman lab for comments on an earlier version of the manuscript. This work was supported, in part, by Grant AI42336 from the NIH to E.A.G., who is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

References

- Aranda CMA, Swanson JA, Loomis WP, Miller SI. Salmonella typhimurium activates virulence gene transcription within acidified macrophage phagosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:10079–10083. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bearson BL, Wilson L, Foster JW. A low pH-inducible, PhoPQ-dependent acid tolerance response protects Salmonella typhimurium against inorganic acid stress. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2409–2417. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.9.2409-2417.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breazeale SD, Ribeiro AA, Raetz CRH. Origin of lipid A species modified with 4-amino-4-deoxy-l-arabinose in polymyxin-resistant mutants of Escherichia coli: an aminotransferase (ArnB) that generates UDP-4-amino-4-deoxy-l-arabinose. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:24731–24739. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304043200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brumell JH, Grinstein S. Salmonella redirects phagosomal maturation. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2004;7:78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamnongpol S, Dodson W, Cromie MJ, Harris ZL, Groisman EA. Fe(III)-mediated cellular toxicity. Mol Microbiol. 2002;45:711–719. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherepanov PP, Wackernagel W. Gene disruption in Escherichia coli– TcR and KmR cassettes with the option of Flp-catalyzed excision of the antibiotic-resistance determinant. Gene. 1995;158:9–14. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00193-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis RW, Bolstein D, Roth JR. Advanced Bacterial Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado MA, Mouslim C, Groisman EA. The PmrA/PmrB and RcsC/YojN/RcsB systems control expression of the Salmonella O-antigen chain length determinant. Mol Microbiol. 2006;60:39–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dell CL, Neely MN, Olson ER. Altered pH and lysine signaling mutants of cadC, a gene encoding a membrane-bound transcriptional activator of the Escherichia coli cadBA operon. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:7–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster JW. Low pH adaptation and the acid tolerance response of Salmonella typhimurium. Crit Rev Microbiol. 1995;21:215–237. doi: 10.3109/10408419509113541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster JW. Escherichia coli acid resistance: tales of an amateur acidophile. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:898–907. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster JW, Hall HK. Adaptive acidification tolerance response of Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:771–778. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.2.771-778.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons HS, Kalb SR, Cotter RJ, Raetz CRH. Role of Mg2+ and pH in the modification of Salmonella lipid A after endocytosis by macrophage tumour cells. Mol Microbiol. 2005;55:425–440. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groisman EA, Mouslim C. Sensing by bacterial regulatory systems in host and non-host environments. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4:705–709. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groisman EA, Heffron F, Solomon F. Molecular genetic analysis of the Escherichia coli phoP locus. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:486–491. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.2.486-491.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunn JS, Lim KB, Krueger J, Kim K, Guo L, Hackett M, Miller SI. PmrA-PmrB-regulated genes necessary for 4-aminoarabinose lipid A modification and polymyxin resistance. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:1171–1182. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunn JS, Ryan SS, Van Velkinburgh JC, Ernst RK, Miller SI. Genetic and functional analysis of a PmrA-PmrB-regulated locus necessary for lipopolysaccharide modification, antimicrobial peptide resistance, and oral virulence of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Infect Immun. 2000;68:6139–6146. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.11.6139-6146.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall HK, Foster JW. The role of Fur in the acid tolerance response of Salmonella typhimurium is physiologically and genetically separable from its role in iron acquisition. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5683–5691. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.19.5683-5691.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J Mol Biol. 1983;166:557–580. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwama T, Ito Y, Aoki H, Sakamoto H, Yamagata S, Kawai K, Kawagishi I. Differential recognition of citrate and metal-citrate complex by the bacterial chemoreceptor Tcp. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:17727–17735. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601038200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato A, Groisman EA. Connecting two-component regulatory systems by a protein that protects a response regulator from dephosphorylation by its cognate sensor. Gene Dev. 2004;18:2302–2313. doi: 10.1101/gad.1230804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kox LFF, Wosten MMSM, Groisman EA. A small protein that mediates the activation of a two-component system by another two-component system. EMBO J. 2000;19:1861–1872. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.8.1861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leaphart AB, Thompson DK, Huang K, Alm E, Wan XF, Arkin A, et al. Transcriptome profiling of Shewanella oneidensis gene expression following exposure to acidic and alkaline pH. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:1633–1642. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.4.1633-1642.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Hsu FF, Turk J, Groisman EA. The PmrA-regulated pmrC gene mediates phosphoethanolamine modification of lipid A and polymyxin resistance in Salmonella enterica. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:4124–4133. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.13.4124-4133.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J, Edwards RA, Wong JJW, Manchak J, Scott PG, Frost LS, Glover JN. Protonation-mediated structural flexibility in the F conjugation regulatory protein, TraM. EMBO J. 2006;25:2930–2939. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig MG, Vanek M, Guerini D, Gasser JA, Jones CE, Junker U, et al. Proton-sensing G-protein-coupled receptors. Nature. 2003;425:93–98. doi: 10.1038/nature01905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGowan CC, Necheva AS, Forsyth MH, Cover TL, Blaser MJ. Promoter analysis of Helicobacter pylori genes with enhanced expression at low pH. Mol Microbiol. 2003;48:1225–1239. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchal K, De Keersmaecker S, Monsieurs P, van Boxel N, Lemmens K, Thijs G, et al. In silico identification and experimental validation of PmrAB targets in Salmonella typhimurium by regulatory motif detection. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R9. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-2-r9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JH. Experiments in Molecular Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Nishino K, Hsu FF, Turk J, Cromie MJ, Wosten MM, Groisman EA. Identification of the lipopolysaccharide modifications controlled by the Salmonella PmrA/PmrB system mediating resistance to Fe(III) and Al(III) Mol Microbiol. 2006;61:645–654. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05273.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulus H, Gray E. The biosynthesis of polymyxin B by growing cultures of Bacillus polymyxa. J Biol Chem. 1964;239:865–871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roland KL, Martin LE, Esther CR, Spitznagel JK. Spontaneous PmrA mutants of Salmonella typhimurium LT2 define a new two-component regulatory system with a possible role in virulence. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:4154–4164. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.13.4154-4164.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rychlik I, Barrow PA. Salmonella stress management and its relevance to behaviour during intestinal colonization and infection. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2005;29:1021–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin D, Groisman EA. Signal-dependent binding of the response regulators PhoP and PmrA to their target promoters in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:4089–4094. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412741200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slonczewski JL, Rosen BP, Alger JR, Macnab RM. pH homeostasis in Escherichia coli: measurement by 31P nuclear magnetic resonance of methylphosphonate and phosphate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:6271–6275. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.10.6271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snavely MD, Gravina SA, Cheung TT, Miller CG, Maguire ME. Magnesium transport in Salmonella typhimurium– regulation of MgtA and MgtB expression. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:824–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soncini FC, Groisman EA. Two-component regulatory systems can interact to process multiple environmental signals. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6796–6801. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.23.6796-6801.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soncini FC, Vescovi EG, Groisman EA. Transcriptional autoregulation of the Salmonella typhimurium phoPQ operon. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4364–4371. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.15.4364-4371.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soncini FC, Vescovi EG, Solomon F, Groisman EA. Molecular basis of the magnesium deprivation response in Salmonella typhimurium: identification of PhoP-regulated genes. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5092–5099. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.17.5092-5099.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamayo R, Prouty AM, Gunn JS. Identification and functional analysis of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium PmrA-regulated genes. FEMS Immunol Med Mic. 2005;43:249–258. doi: 10.1016/j.femsim.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanford C, Roxby R. Interpretation of protein titration curves. Application to lysozyme. Biochemistry. 1972;11:2191–2198. doi: 10.1021/bi00761a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tews N, Findeisen F, Sinning I, Schultz A, Schultz JE, Linder JU. The structure of a pH-sensing mycobacterial adenylyl cyclase holoenzyme. Science. 2005;308:1020–1023. doi: 10.1126/science.1107642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trent MS, Ribeiro AA, Lin SH, Cotter RJ, Raetz CRH. An inner membrane enzyme in Salmonella and Escherichia coli that transfers 4-amino-4-deoxy-l-arabinose to lipid A – induction in polymyxin-resistant mutants and role of a novel lipid-linked donor. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:43122–43131. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106961200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker DL, Tucker N, Conway T. Gene expression profiling of the pH response in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:6551–6558. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.23.6551-6558.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vescovi EG, Soncini FC, Groisman EA. Mg2+ as an extracellular signal: environmental regulation of Salmonella virulence. Cell. 1996;84:165–174. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinrick B, Dunman PM, McAleese F, Murphy E, Projan SJ, Fang Y, Novick RP. Effect of mild acid on gene expression in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:8407–8423. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.24.8407-8423.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winfield MD, Groisman EA. Role of nonhost environments in the lifestyles of Salmonella and Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:3687–3694. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.7.3687-3694.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe AJ. The acetate switch. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2005;69:12–50. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.69.1.12-50.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wosten MMSM, Groisman EA. Molecular characterization of the PmrA regulon. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:27185–27190. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.38.27185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wosten MMSM, Kox LFF, Chamnongpol S, Soncini FC, Groisman EA. A signal transduction system that responds to extracellular iron. Cell. 2000;103:113–125. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00092-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao YX, Jansen R, Gaastra W, Arkesteijn G, van der Zeijst BAM, van Putten JPM. Identification of genes affecting Salmonella enterica serovar enteritidis infection of chicken macrophages. Infect Immun. 2002;70:5319–5321. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.9.5319-5321.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou ZM, Ribeiro AA, Lin SH, Cotter RJ, Miller SI, Raetz CRH. Lipid A modifications in polymyxin-resistant Salmonella typhimurium: PmrA-dependent 4-amino-4-deoxy-l-arabinose, and phosphoethanolamine incorporation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:43111–43121. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106960200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]