Abstract

The pilot qualitative study presented in this article explored women's perceptions of the doula support they received in the perinatal period, with the aim of describing details of their experiences. Study participants were 12 women who had hospital births with the support of a certified doula. In-depth interviews were conducted postpartum with all 12 participants. Interview topics included specific categories and aspects of doula support and whether participants would use and/or recommend doulas in the future. Transcripts were analyzed using content analysis. Emerging themes included support for husbands, tailored approaches, reassurance and encouragement, fulfillment of the women's desire for support from an experienced woman, and praise for the doula. The findings suggest that the doulas were beneficial in multiple areas for their clients.

Keywords: doula, labor and birth support, birth experience

The Greek word “doula” has changed in scope since its introduction in Dana Raphael's book, The Tender Gift: Breastfeeding (Raphael, 1973). The term was originally used to describe a woman who provides postpartum care. The word “doula” has now expanded to encompass a woman dedicated to providing physical, emotional, informational, and advocacy support to women during the pre-, peri-, and postnatal periods (Kayne, Greulich, & Albers, 2001; Klaus, M., Kennell, & Klaus, P., 2002). The use of doulas is gaining popularity throughout North America. However, few investigations have examined how childbearing women view the care provided by their doulas.

In a Maternity Center Association survey of a national sample of 1,583 women, 79 (5%) reported having a doula, defined as a trained labor assistant present at their birth (Declercq, Sakala, Corry, Applebaum, & Risher, 2002). Results also indicated that doulas were rated highest in terms of quality of supportive care during labor when compared to midwives, family members or friends, husbands/partners, doctors, and nursing staff.

The positive impact of labor support by doulas on obstetrical outcomes has been reported in a number of studies (Hodnett, Gates, Hofmeyr, & Sakala, 2004), but a comprehensive examination of women's overall experiences with doula support has received less attention (Campero et al., 1998). The purpose of the current pilot qualitative study was to investigate the experiences of childbearing women who received doula support during the perinatal period.

METHODS

Data Collection

Women who were eligible for participation in the study were between the ages of 18 and 50 years old, had had a hospital birth, would be 6 to 20 weeks postpartum at the time of the interview, and could speak and read English. Participants also had to have been accompanied by a certified doula at their most recent birth. Although the numerous doula-certifying agencies differ, certification generally requires didactic coursework, attendance at births, and documentation of the support provided. It is important to note that certification does not signify standardization of education or experience. Additionally, the study focus was on the women's experience of doula care, and information about individual doula experience was not collected.

Recruitment took place through the assistance of certified doulas in the Puget Sound area of Washington State. The primary researcher attended meetings of two doula organizations to explain the study and provide study information forms to more than 40 doulas to give to their clients. Doulas also had the option of contacting clients by e-mail or telephone to explain the study and, then, mailing the client a self-addressed, stamped envelope with the study information. Participating doulas received a script to use in describing the study to prospective participants.

Women who agreed to be contacted provided contact information and returned it to the investigator in a self-addressed, stamped envelope. Upon receipt of the form, the investigator contacted the prospective subject to screen for eligibility, answered any general questions, and scheduled an interview. Subjects received a $10 cash incentive on completion of the interview. Interviews, which averaged 60 minutes, were conducted with 12 women in their homes between 7 and 16 weeks postpartum. Interview topics included four categories of doula support (physical, emotional, informational, and advocacy), specific aspects of support, and future use and recommendation of doulas. Transcripts were analyzed using content analysis.

Participant Demographic Characteristics

Thirteen women were contacted and volunteered to participate in the study. One woman was excluded because her most recent birth was a home birth, leaving a sample of 12 women. The average age was 33.4 years old, with a range from 30 to 37 years old. In general, the participants were Euro-American, upper-middle class, well educated, and partnered. The reported ethnic background of eight women was white; two women were Asian or Pacific Islander, and two were mixed ethnicity. The average income was $72,363 per family, with a range from below $30,000 to above $91,000. All had completed some postsecondary education, differing only in the type of degree they received, with a range from associate degree to graduate degree. All participants reported having a male partner, and 11 were married. The women themselves paid for the doula services. A consultant for Pacific Association for Labor Support stated that the study's sample of self-pay clientele is representative of Washington State, as doula services are not customarily covered by a third-party payer (S. Capestany, personal communication, April 2003).

Participant Pregnancy and Birth Outcomes

Pregnancy and birth outcomes were similar for the participants. Eleven women were primiparous and one woman was multiparous. All 11 of the primiparous women attended childbirth education classes. Ten of the births were vaginal, and two were cesarean. The gestational age of the newborn averaged 40.29 weeks, with a range from 38 to 42 weeks.

The number and composition of birth companions varied considerably. Eleven of the 12 women reported having their partners present; six women reported having a family member(s) present; two women reported having a friend(s) present; all had nurses present; and 11 reported having doula(s) present (one doula was not present at a cesarean birth). Six women reported that their providers were present during labor, and 11 had physicians present during birth. One participant had a midwife present for both labor and birth.

Complications and/or interventions were varied, mainly in the use of epidural anesthesia/analgesic, the use of oxytocin, and labor duration. Half of the sample (six) gave birth in one hospital, two gave birth in another hospital, and the remaining four gave birth in other hospitals, for a total of six different hospitals. The reported newborn gender included six female babies and six male babies.

Data Analysis

The current study used content analysis. Content analysis is conducted by identifying, coding, and categorizing primary patterns that emerge from the data (Krippendorf, 1980; Patton, 1990). A set of codes was created after the primary investigator reviewed the transcripts. Morse and Field (1995) describe codes as being derived from “persistent words, phrases, or themes within the data” (p. 132). Codes were labeled manually in the margins of the transcripts, followed by a test for reliability. After reliability was reached, a data matrix, defined as a table of cases and their associated variables, was created.

For the present study, the cases were the subjects and the variables were the codes, some of which were combined to create a theme. A tally within the matrix was completed to note how many times per interview each code/theme was mentioned by each subject. Finally, an average was calculated for each theme.

Three types of reliability are distinguished: stability, reproducibility, and accuracy (Krippendorf, 1980). Stability, or “intraobserver reliability,” indicates that a process does not change over time. It is used when the same coder codes the same data at various points in time. Stability can detect inconsistencies, but it is the weakest type of reliability. Reproducibility, or “intercoder reliability,” is found when multiple coders at multiple locations reach consensus on coding. Reproducibility is considered a more robust method than stability. The most powerful method of measuring reliability in content analysis is accuracy. Accuracy is assessed by comparing coder or instrument performance against a gold-standard performance or measure (Krippendorf, 1980).

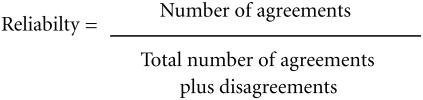

Because this study had a single coder and no standard measurement or tools existed, stability was used. Stability is an appropriate method of evaluating reliability for narrative data (Downe-Wamboldt, 1992). Stability is achieved by conducting periodic checks throughout the coding process as well as analysis for consistency. For the current study, the intrarater agreement was in the 90th percentile range. The formula used to calculate agreement percentages is presented in the Figure.

Figure Reliability Formula Used to Calculate Agreement Percentages*

RESULTS

Analysis of the interviews indicated that the study participants had positive experiences with their doula support. Doulas were able to assist the women in meeting their birth expectations, and the women often stated that doulas provided exceptional support. Themes that emerged from analysis included the following: support for husbands, tailored approaches, reassurance and encouragement, the ability to fulfill the women's desire for the support of an experienced woman, and praise for the doula.

Analysis of the interviews indicated that the study participants had positive experiences with their doula support.

Support for Husbands: Doulas Are Not Just for Pregnant Women

Although the mother was the focus of support, study participants mentioned that their doula(s) also provided support for their husbands. The 11 married participants mentioned support for their husbands at least once and an average of 2.5 times per interview. Most women wanted someone to support their husbands, and one woman felt it was not the husband's role to be the sole provider of labor support. One woman said she wanted the doula to “help keep my husband under control.” When asked if she would have a doula again, the woman replied, “Absolutely…my husband is sold on it.” Women also mentioned that the doula had knowledge that their husbands, who had no prior experience with the birth process, did not have. Four women mentioned that doulas offered relief to their husbands, allowing them to eat, rest, take a break, and sleep. The support for the husbands was twofold: The doula(s) helped the husbands help their wives and provided direct support for the husbands.

Providing a Tailored Approach

Two codes—“specific support for the individual woman” and “focus on the woman”—were combined as a theme of a “tailored approach.” All study participants stated one or both of these ideas in the interview, averaging three times per interview.

The concept of individual care is linked to the notion that each woman's birth experience is its own event. One study participant highlighted this notion saying, “I believe every woman is different, every childbirth experience is different.”

As previously stated, the women received support from their doulas in all four major doula-support categories (physical, emotional, informational, and advocacy). The doulas' support for the women's individual needs before labor included such assistance as providing home-baked cookies, offering a follow-up phone call, and clarifying the birth plan. During labor, support included providing massage, protecting the woman's peace, holding a hand, and simply sitting next to the woman as she stared at a crack on the floor. One study participant stated, “It was whatever I wanted, and whatever I needed was the most important thing.”

Overall, the women felt that their doula(s) were attentive to their needs. Participants also mentioned several times that they felt the doula was focused solely on her client and that, unlike the medical providers, the doulas did not have to take care of anyone else.

Reassurance and Encouragement

The terms and concepts surrounding reassurance and encouragement emerged in 11 of 12 interviews, averaging 2.9 times an interview. Reassurance and encouragement were not mentioned in the interview with a second-time mother.

The reassurance and encouragement that doulas provided the study participants included assisting the women to prepare for the birth, to make it through labor, and to cope with the pain of labor, and assuring the woman that she was doing well throughout her labor. Two study participants stated that reassurance and encouragement were the exclusive forms of support their doula gave them. Participants' statements that provided examples of encouragement and reassurance from their doula(s) included, “She was very encouraging at every stage I was in” and “Without a doula to help reassure that ‘yes, this will hurt,’ it could easily be overwhelming.” One woman reported that her doula was “serene” and that “her serenity helped me realize that it was going to be okay.” In another context, a woman stated that her doulas helped her to ask questions of her care providers and assisted her to set boundaries with a family member.

The Support of a Woman Experienced in Childbirth

The importance of having the presence of a woman who is experienced in childbirth, either personally or through training, was mentioned in all interviews, with an average of two times per interview. Many study participants reported wanting someone who had “done it before.” Others felt that, even if their doula had not had her own childbirth experience, she was trained to provide physical and emotional support along with the fundamentals of pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period. Participants reported feeling good about the fact that their doula had attended many births and had been through the birth experience herself (although not all doulas have). Additionally, participants reported feeling encouraged by the fact that a woman was present to provide physical support. For example, one woman stated, “There is a time when a woman's touch is just better.” Another woman commented, “I know that's not a popular notion, but my opinion is it's kind of a woman's work, a woman's job, and women should support other women.” Two women discussed historical practices of women supporting other women in childbirth. One of the two women mentioned that having a doula is “sort of circling back to that time, it makes great sense.” Another participant reported, “It really connected me with…the cosmic woman connection. Just that ages of women have been doing this…it's not the same [as in the past], but it's the same result. You tie into this ancient energy.” Additionally, one study participant said:

You want to have a woman who has been through it before, who's there when you get to a point where you just can't deal with it anymore, that you have somebody else [doula] that's there going, “Yes, I'm here, I did it, it's okay, you can handle it.” If it's a man telling me that, I'm not going to buy it…I need more realism than that.

Praise for the Doula

All study participants made comments in praise of their doula(s). Comments of praise were made an average of 2.7 times per interview. The participants' remarks were spontaneous and included brief phrases such as:

“She was really good.”

“She was on the top of her game.”

“I just think they are wonderful.”

“I had the utmost confidence in her.”

“Great and fabulous.”

“Amazing, the best.”

“I was impressed.”

“We loved our doula.”

Participants reported feeling encouraged by the fact that a woman was present to provide physical support.

DISCUSSION

The current study's findings suggest that doulas are beneficial to their clients in many areas. By providing unique and exclusive support tailored to meet each woman's specific needs, doulas assist women in achieving the birth experience they desire. Additionally, 11 of the 12 study participants reported they would choose to have a doula again, and all reported they would recommend doulas to other women. The women were also fond of their doulas and had high regard for their support. Only one participant stated that she and her husband might not want a doula again because they had learned so much from their doulas and, therefore, might not need one at their next birth.

The women in the current study's sample had the same model of doula contact and support. The model of doula contact included selecting a doula, having both prenatal and postpartum visits, and having the doula present at the hospital for the birth. The women also received similar types of emotional, physical, and informational support and advocacy. The similarity may be the result of doula certification, which emphasizes this model and philosophy of care. The form of care participants received may have influenced their perceptions. Other possible types of doula care include an on-call system or a coordinator who selects the doula. In these models of care, the woman does not choose the doula herself. The on-call version entails the doula meeting the woman for the first time at the birth; thus, no prenatal component exists, and a postpartum component may or may not be present. The coordinator-selection version can put the doula in contact with the woman prenatally; however, the prenatal and postpartum contact can vary on an individual basis or by program.

Although few studies have examined women's experiences with doulas, the findings of the current study are comparable to those of a hospital-based study conducted in Mexico, which evaluated the psychosocial support given to laboring women by doulas (Campero et al., 1998). In both studies, women spoke of the advantages of doula support during times of doubt. For example, the studies found that doulas meet informational needs, helping women understand medical interventions and language and providing reassurance about the birth process in general. Additionally, women in both studies reported feeling they were part of the birth process and were, for the most part, active participants in that they felt a sense of control over their experience. Women in both studies also reported feelings of satisfaction, having the opportunity to ask questions and receiving emotional support. A final similarity in findings consists of a “deep need for company, empathy, and concrete assistance” (Campero et al., 1998, p. 402), especially for first-time mothers, which was provided by the doulas in both studies.

Significant findings include women choosing a doula because they desire support by a woman experienced in childbirth. The women also expressed a wish for the support of their husbands.

The current pilot qualitative study is unique in its examination of the use of certified doulas with a self-pay clientele. Significant findings also include women choosing a doula because they desire support by a woman experienced in childbirth. The women also expressed a wish for the support of their husbands. These themes have not been examined in previous studies and may contribute information to both doulas and providers about their clients' needs.

Study Limitations

Generalization is limited by the homogeneity and small size of the sample. The experiences of women who were missing from the sample (e.g., single women, lesbian or bisexual women, multiparous women, significantly younger or older women, women with poor infant outcomes, low-income women, non-English speakers, or women who were dissatisfied with their doula) may be quite different. Other limitations to generalization include varying institutional procedures, policies, and protocols for both staff and doulas that may influence women's birth experiences. Although the study's sample was representative of western Washington, it may not be similar to other regions in the United States.

Another limitation is that selection bias occurred on two fronts. First, doulas selected the clients to recruit as potential subjects and, second, women self-selected to participate in the study. The experiences of the women who were eligible but did not participate are unknown and could differ from those described in the present sample. Doulas and subjects may have chosen to be in the study based mainly on a positive outcome or experience. Therefore, negative outcomes or experiences could be missing from the sample.

Additionally, the sample consisted mainly of primiparous women. Although the one multiparous participant had many experiences similar to those of the other participants, her experiences cannot be assumed to be typical of other multiparous women.

IMPLICATIONS FOR RESEARCH AND PRACTICE

The fact that only two qualitative studies (in very different settings) have been conducted on doula support suggests a need for further research to compare analyses and to further identify the effects and methods of doula support. A larger, multisite study including a more demographically and geographically diverse sample would be beneficial. Moreover, both qualitative and quantitative studies in the future might explore other questions, such as the perceptions of husbands/partners of women who receive doula care and the associations between doula care and the clients' satisfaction with the birth experience. In addition, more research is warranted to examine the doula's work and experiences.

In the current study, women found doula support to be extremely positive. Including information about the role of doula care in education programs for physicians and nurses, in continuing education classes, and in childbirth education classes would encourage cross-disciplinary practices that ultimately benefit the childbearing family. In addition to the positive points identified in this study, doula services provided at the hospital may offer additional support to the labor-and-birth team, thereby relieving part of the burden on the staff while maintaining adequate support for the laboring woman and her family. Doula support also has the potential to increase a woman's satisfaction with her birth experience.

With their potential to increase patient satisfaction, doula services provided in the hospital may also help increase the facility's revenue. The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) focuses on the patient's experience of care; what used to be identified as “patient satisfaction” is now more inclusively focused on the patient's perception of care. The JCAHO's Comprehensive Accreditation Manual for Hospitals states that the organization “collects data on the perception of care… to better measure the performance of organizations meeting the needs, expectations and concerns of the clients” (JACHO, 2006, Criterion PI.1.10, EP 3). Consequently, patient satisfaction/perception of care is an important business issue for hospitals. Such satisfied “customers” may likely refer friends and family members to the facility, thereby generating more revenue for the hospital to support these and other family-friendly services.

If doulas can be linked to improved outcomes, potential health benefits to the childbearing population, as well as cost savings to the health-care system, may be realized.

Examining women's experiences with doula support can provide insight into best practices. Ultimately, the information may fill the gap in knowledge about how doulas may influence obstetric and infant outcomes—information that would greatly benefit public health-care practices and, specifically, maternal- and child-health-care practices. If doulas can be linked to improved outcomes, potential health benefits to the childbearing population, as well as cost savings to the health-care system, may be realized.

As Penny Simkin (1991) notes, “[T]he birth experience has a powerful effect on women with a potential for permanent or long-term positive or negative impact” (p. 210). Supportive care provided by doulas may increase the potential for a positive, long-term effect.

Acknowledgments

The researchers thank all participants in this study; Solmaz Shotorbani for reviewing the manuscript; and Michelle Bell, PhD, and Penny Simkin, PT, for their instruction and support in this investigation. The study was supported by grant 6T76 MC 00011 from the Maternal and Child Health Bureau (Title V, Social Security Act), the Health Resources and Services Administration, and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Footnotes

From Miles, M., & Huberman, A. M. (1984). Qualitative data analysis: A sourcebook of new methods. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

References

- Campero L, Garcia C, Diaz C, Ortiz O, Reynoso S, Langer A. “Alone, I wouldn't have known what to do”: A qualitative study on social support during labor and delivery in Mexico. Social Science and Medicine. 1998;47(3):395–403. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00077-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Declercq E. R, Sakala C, Corry M. P, Applebaum S, Risher P. 2002. Listening to mothers: Report of the first national U.S. survey of women's childbearing experiences. New York: Maternity Center Association. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downe-Wamboldt B. Content analysis: Method, applications, and issues. Health Care for Women International. 1992;13(3):313–321. doi: 10.1080/07399339209516006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodnett E, Gates S, Hofmeyr G. J, Sakala C. 2004. Continuous support for women during childbirth (Cochrane Review). In The Cochrane Library, 1, 2004. Chichester, UK:John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- 2006. Comprehensive accreditation manual for hospitals: The official handbook. Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations [JCAHO]. Oak Brook Terrace, IL: Joint Commission Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Kayne M, Greulich M, Albers L. Doulas: An alternative yet complimentary addition to care during childbirth. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2001;44(4):692–703. doi: 10.1097/00003081-200112000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaus M, Kennell J, Klaus P. 2002. The doula book. Cambridge, MA: Perseus Books. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorf K. 1980. Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Miles M, Huberman A. M. 1984. Qualitative data analysis: A sourcebook of new methods. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Morse J. M, Field P. A. 1995. Qualitative research methods for health professionals (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Patton M. Q. 1990. Qualitative evaluation and research method (2nd ed.). Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Raphael D. 1973. The tender gift: Breastfeeding. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Simkin P. Just another day in a woman's life? Women's long-term perceptions of their first birth experience. Part 1. Birth. 1991;18(4):203–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536x.1991.tb00103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]