Abstract

BACKGROUND

This study was performed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of paclitaxel with cisplatin as salvage therapy in patients previously treated with gemcitabine and cisplatin (G/C) for advanced transitional cell carcinoma (TCC) of the urothelial tract.

METHODS

Twenty-eight patients with metastatic or locally advanced TCC who had received prior G/C chemotherapy were enrolled. All patients received paclitaxel (175 mg/m2) and cisplatin (60 mg/m2) every 3 weeks for eight cycles or until disease progression.

RESULTS

The median age was 61 years (range, 43–83 years), and the median Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status was 1 (range, 0–2). The overall response rate was 36% [95% confidence interval (95% CI) = 18–54], with three complete responses and seven partial responses. The median time to progression was 6.2 months (95% CI = 3.9–8.5), and the median overall survival was 10.3 months (95% CI = 6.1–14.1). The most common Grade 3/4 nonhematologic and hematologic toxicities were emesis (10 of 28 patients; 36%) and neutropenia (5 of 110 cycles; 5%).

CONCLUSIONS

Salvage chemotherapy with paclitaxel and cisplatin displayed promising results with tolerable toxicity profiles in patients with metastatic or locally advanced TCC who had been pretreated with G/C.

Keywords: Paclitaxel, cisplatin, transitional cell carcinoma, salvage therapy, urothelium

Introduction

Transitional cell carcinoma (TCC) of the urothelium is characteristically a chemosensitive tumor [1]. Combination chemotherapy provides both palliation and modest survival advantage in patients with advanced disease states. Cisplatin-based combination chemotherapy, such as M-VAC (methotrexate, vinblastin, doxorubicin, cisplatin), produced considerable tumor responses of 50% to 70% and durable improvements in survival in 15% to 20% of patients [2–5]. A randomized clinical phase III study reported that M-VAC, when compared to cisplatin alone, had superior response rates in patients with metastatic urothelial cell carcinoma [6]. As first-line chemotherapy, the combination of gemcitabine and cisplatin (G/C) also demonstrated noninferior antitumor activity but better tolerability and improved safety profile when compared with M-VAC [7]. As a result, the G/C combination has become a popular regimen for the first-line treatment of TCC. However, almost all responding patients relapse within the first year, with a median survival of 12 to 14 months. In addition, prognosis is very poor in patients who display progressive disease after receiving combination cisplatin-based chemotherapy. Therefore, options for salvage therapy have become important. However, the standard chemotherapeutic regimen for salvage treatment remains to be defined. Clinical trials for second-line chemotherapy for advanced urothelial TCC are warranted [8,9].

Taxane-based chemotherapy is currently the most commonly used regimen for salvage chemotherapy. Paclitaxel has been tested as a single agent in both first-line and second-line chemotherapies and has shown response rates of between 42% and 56% with 3-week cycle therapy schedules [10–12]. However, weekly paclitaxel has demonstrated a low response rate of 10% and short time to progression (TTP) when used as salvage therapy for advanced TCC in small phase II trials [11,13].

Based on these promising results of taxane-based chemotherapy and given the absence of standard second-line treatment options, we conducted a phase II study of paclitaxel with cisplatin as salvage therapy for patients with advanced TCC who had been previously treated with G/C chemotherapy.

Materials and Methods

Patients and Treatment Scheme

From August 2002 to December 2004, patients with histologically confirmed TCC of the urinary tract (bladder, ureter, and renal pelvis) were entered into the study. Eligible patients were required to have had progressive disease subsequent to a G/C combination chemotherapy, an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0 to 2, and lesions bidimensionally measurable by spiral computed tomography (CT) scan. Adequate bone marrow, liver, and renal functions were defined as follows: absolute neutrophil count ≥ 1500 µl; platelet count ≥100,000 µl; bilirubin < 1.5x the upper normal level (UNL); aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase < 2 UNL; and creatinine ≤ 1 UNL. Patients with other malignancies or with concurrent uncontrolled medical illness were deemed ineligible for the study. All patients provided written informed consent according to our institutional guidelines.

The treatment cycle included intravenous paclitaxel (175 mg/m2) for 3 hours on day 1; following paclitaxel infusion, cisplatin (60 mg/m2) was administered intravenously for 1 hour, with adequate hydration. Before paclitaxel infusion, all patients were prophylactically administered 100 mg of hydrocortisone, 4 mg of chlorpheniramine, and 50 mg of ranitidine 30 minutes before treatment. The treatment was then repeated every 3 weeks and continued until disease progression or up to eight cycles.

Study Objectives

The objective of the study was to evaluate the safety and efficacy of paclitaxel plus cisplatin as salvage chemotherapy in patients with advanced urothelial TCC who had been previously treated with G/C. The primary end point of this study was the response rate to chemotherapy. Secondary end points included TTP, overall survival (OS), and toxicity.

Statistical Analysis

Treatment responses for measurable disease were assessed by spiral CT scans conducted every three cycles of treatment. Tumor responses were defined as World Health Organization criteria. OS and response duration were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier product limit method. OS duration was measured from the day of chemotherapy initiation up to the day of death. If the patient was lost during the follow-up period, the status of the patient was confirmed by telephone with the bereaved family at the time of analysis. TTP was calculated from the day of treatment initiation up to the date when progression was noted. Toxicity was measured according to National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria, version 2.0.

The target response rate of interest was ≥ 25%, whereas the accrual of patients for the study would be held if the response probability was ≤ 5%. Nine patients would be accrued initially in a two-stage study design. If at least one complete or partial response was noted, an additional eight patients would be accrued. Nineteen patients were actually enrolled in the second stage, for a total of 28 patients. The probability of accepting the study regimen with a response probability of < 5% was .20, and the probability of rejecting the study regimen with a response probability of > 25% was .05.

Results

Patients

Nine patients were enrolled from August 2002 to June 2003. Then, an additional nineteen patients were recruited from July 2003 to December 2004. Baseline patient profiles and patient characteristics are provided in Table 1. The median age was 61 years (range, 43–83 years), with a predominantly male proportion [males, 21 (75%); females, 7 (25%)]. The most common primary site was the bladder (71%). The most frequently involved site of metastases was the lung (43%), followed by the bones (29%) and liver (29%). Twenty-one patients (75%) received G/C chemotherapy alone, whereas the remaining seven patients (25%) received G/C chemotherapy in combination with radiotherapy as first-line treatment. The median number of G/C cycles was 5 (range, 2–12 cycles). Patients who had intra-abdominal metastatic lymph nodes or malignant cells on resected margins after radical surgery received chemotherapy with radiotherapy. Patients who received G/C with radiotherapy (4000 cGy, 16 fractions) underwent six cycles of G/C chemotherapy. Patients' median time to disease progression with G/C was 6.8 months [95% confidence interval (95% CI) = 1.8–32.7 months]. Ten patients had progressive diseases within 6 months of G/C initiation. Seventeen patients (71%) were responders to prior treatment with G/C. Responders' median response duration of G/C was 7.5 months (95% CI = 4.8–10.2 months).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients.

| Characteristics | n (%) |

| Total | 28 (100) |

| Age in years [median (range)] | 61 (43–83) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 21 (75) |

| Female | 7 (25) |

| ECOG performance status | |

| 0 | 2(7) |

| 1 | 25(89) |

| 2 | 1(4) |

| Primary site | |

| Bladder | 20 (71) |

| Ureter | 7 (25) |

| Renal pelvis | 1 (4) |

| Initial tumor grade | |

| Unknown | 1 (4) |

| 2 | 2 (7) |

| 3 | 25 (89) |

| Metastatic lesions on initiation of paclitaxel and cisplatin | |

| Lung | 12 (43) |

| Bone | 8 (29) |

| Liver | 8 (29) |

| Metastatic lymph nodes without visceral metastasis | 7 (25) |

| Previous treatment | |

| Chemotherapy alone | 21 (75) |

| Chemoradiotherapy | 7 (25) |

| Best response to first-line therapy | |

| Complete response | 8 (29) |

| Partial response | 9 (32) |

| Stable disease | 3 (10) |

| Progressive disease | 8 (29) |

Response and Survival

One of the initial nine patients achieved complete response, and one patient achieved partial response. Therefore, an additional 19 patients were recruited. Finally, 24 (86%) of 28 patients were assessable for response. According to intention-to-treat analysis, three patients (11%; 95% CI = 0–23%) obtained a complete response, and seven patients (25%) obtained a partial response to therapy (95% CI = 9–41%). An overall response rate (ORR) of 36% (95% CI = 18–54%) was achieved. The ORR excluding four inevaluable patients was 42% (95% CI = 22–62%). Four patients who were not evaluable for response composed the inevaluable response group (Table 2). Three inevaluable patients developed neutropenic fever after the first cycle did not proceed with further chemotherapy. One patient suffered from Grade 3 emesis and gave up further chemotherapy after the second cycle.

Table 2.

Response Rates (n = 28).

| Best Response | n (%) |

| Complete response | 3 (11) |

| Partial response | 7 (25) |

| Stable disease | 6 (21) |

| Progressive disease | 8 (29) |

| Inevaluable | 4 (14) |

| ORR | 10 (36) (95% CI = 18 -54%) |

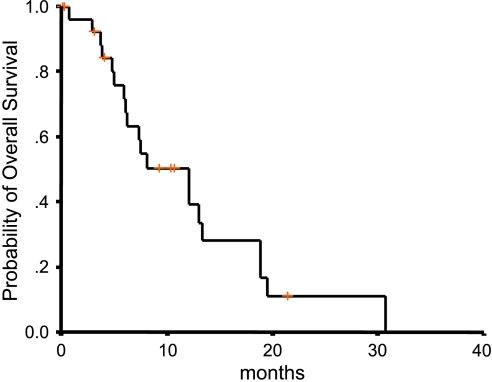

After a median follow-up duration of 16.4 months (range, 2.1–30.7 months), the median OS of all 28 patients was 10.3 months (95% CI = 6.1–14.1 months) and the 1-year survival rate was 45% (95% CI = 27–63%) (Figure 1). Twelve patients remained alive at the time of analysis. One of the survivors stopped chemotherapy due to neutropenic fever and was followed up for only 2.1 months.

Figure 1.

Survival curve.

The median TTP for the 24 evaluable patients was 6.2 months (95% CI = 3.9–8.5 months). The median response duration was 4.7 months (95% CI = 2.8–6.6 months). Among the three complete-response patients, two patients had lung metastases from bladder cancer and the other had intraabdominal lymph node metastasis from ureteral cancer. One patient with lung metastasis died from an acute left middle cerebral artery infarction but without disease recurrence at 21.4 months.

Seven (41%) of 17 prior G/C responders showed response to paclitaxel and cisplatin compared with 4 (36%) of 11 G/C nonresponders. There was no significant difference in median OS time between the two groups [G/C responders (7.5 months, 95% CI = 4.8–10.2 months) versus G/C nonresponders (9.3 months, 95% CI = 4.4–14.3 months)], as well as in ORR. Among 10 patients with < 6 months of TTP of G/C (G/C refractory group), one complete response and two partial responses were achieved after paclitaxel and cisplatin chemotherapy. The response rate for paclitaxel and cisplatin of the G/C refractory group and that for the nonrefractory group did not show statistically significant differences. However, the number of patients of each subgroup was small, and statistical power might be inconclusive.

Toxicity

One hundred ten cycles, with a median number of three cycles (range, 1–8 cycles), were administered. There was no treatment-related mortality. In addition, ≥ Grade 3 neutropenia occurred in 5% of all cycles and was associated with infection in 3% of all cycles. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor was administered in patients with neutropenic fever. Three patients could not receive further chemotherapy after an episode of neutropenic fever because of deteriorated performance status. Grade 3/4 anemia and thrombocytopenia were observed in one cycle (1%) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Hematologic Toxicities.

| Toxicity | National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria (Per Cycle; n = 110) | |||

| Grade 1 (%) | Grade 2 (%) | Grade 3 (%) | Grade 4 (%) | |

| Neutropenia | 10 (9) | 8 (7) | 3 (3) | 2 (2) |

| Anemia | 55 (50) | 12 (11) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 16 (15) | 3 (3) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Infection with neutropenia | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | ||

| Infection without neutropenia | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) |

Ten (36%) of 28 patients suffered from Grade 3/4 emesis, and one patient refused further chemotherapy after two treatment cycles. Eight patients (29%) experienced Grade 2 peripheral neuropathy, although seven of eight patients already had Grade 1 peripheral neuropathy from previous chemotherapies on study entry (Table 4).

Table 4.

Nonhematologic Toxicities.

| Toxicity | National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria (Per Patient; n = 28) | |||

| Grade 1 (%) | Grade 2 (%) | Grade 3 (%) | Grade 4 (%) | |

| Emesis | 7 (25) | 8 (29) | 10 (36) | 0 (0) |

| Neuropathy | 8 (29) | 8 (29) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Change in bowel habits | 6 (21) | 12 (43) | 3 (11) | 0 (0) |

| Azotemia | 2 (7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) |

Discussion

Systemic chemotherapy is the treatment modality that has been most actively evaluated in patients with advanced or metastatic TCC of the urothelium [14]. Cisplatin is one of the most effective chemotherapeutic agents for metastatic urothelial TCC [15]. In the early 1990s, two prospective randomized trials confirmed the superiority of M-VAC [6,14,16]. Even though M-VAC has been considered the standard treatment of metastatic TCC, its use can be limited due to its associated toxicities: myelosuppression, severe emesis, cardiotoxicity, neurotoxicity, ototoxicity, and nephrotoxicity [17]. Therefore, therapeutic approaches with newer agents are necessary to improve response and survival rates while reducing toxicity profiles [15]. In the past decade, gemcitabine, paclitaxel, docetaxel, and pemetrexed have emerged from clinical development for use in the treatment of TCC [11,18]. A large multinational phase III trial comparing M-VAC with G/C revealed that G/C had similar antitumor activities with better tolerability, which was confirmed by another trial conducted by von der Maase et al. [7,19]. Based on these reports, G/C appeared to be an appropriate alternative for patients with advanced TCC of the urothelium [7,11,18,19]. Nevertheless, long-term survival of patients with advanced TCC of the urothelium is still rare. Because most patients responding to first-line chemotherapy will ultimately die due to disease progression, the role for salvage treatments will be pivotal in improving survival in these patients.

Several small phase II trials as salvage therapy for advanced TCC were documented with relatively unsatisfactory results [11,13,20-23]. A small phase II study for patients with refractory or relapsed urothelial tumors after methotrexate/cisplatin-based regimen was reported [20]. The combination therapy of fluorouracil, folinic acid, and ifosfamide yielded no objective response [20]. Pagliaro et al. [22] investigated the antitumor activity of weekly gemcitabine in combination with cisplatin and ifosfamide in 49 previously treated patients with advanced TCC. An ORR of 40.8% and an OS duration of 9.5 months were reported [22]. Taxane-based chemotherapy is currently the most commonly used regimen in the second-line setting [11]. McCaffrey et al. [21] reported that docetaxel was an active single agent in cisplatin-pretreated patients with urothelial TCC (n = 30; partial response = 13%; median survival = 9 months). A small phase II trial of weekly paclitaxel for salvage therapy demonstrated on ORR of 10% with a median TTP of 2.2 months and a median OS time of 7.2 months [13]. The combination of paclitaxel and carboplatin showed modest activity in cisplatin-pretreated patients with urothelial TCC who had an ORR of 16% (95% CI = 7–30%) with one complete response (2%), two partial responses (5%), and four partial responses (9%) that were unconfirmed. The median progression-free survival was 4 months (95% CI = 3–5 months), and the median survival was 6 months (95% CI = 5–8 months). The predominant Grades 3 and 4 toxicities consisted of myelosuppression in 28 patients and peripheral neuropathy in 11 patients [23].

Our study yielded an ORR of 36% with three complete responses and a median OS of 10.3 months. Several plausible reasons for the high response rate in this study could be attributed to the substitution of carboplatin for cisplatin and/or the fact that the majority of patients were documented responders to previous treatments with G/C (17 partial responses; 60%). However, there was no significant difference in survival or ORR between the G/C responders and the nonresponders. Although reduced nephrotoxicity is an important advantage of carboplatin, a few randomized phase II studies comparing regimens using carboplatin versus cisplatin reported inferior tumor activity with carboplatin-containing regimens [1,24,25]. A randomized phase II study performed in 1996 compared M-VECa (methotrexate, vinblastin, epirubicin, carboplatin) with M-VEC (methotrexate, vinblastine, epirubicin, cisplatin). The study demonstrated an M-VECa response rate of 41%, compared with the 71% response rate of M-VEC (P = .04) [25]. Bellmunt et al. [24] reported 39% response rates with M-CAVI (methotrexate, carboplatin, vinblastine) compared with 52% of M-VAC in a small randomized trial (P = NS). Prospective randomized phase III trials are warranted to confirm differences in tumor activity between carboplatin and cisplatin. A possible reason for the observed response rates could be that most of the patients (96%) had an ECOG performance status of 0 or 1, whereas other similar phase II studies included less patients with good performance (77% with a ECOG performance status of 0 or 1) [23]. In addition, the inclusion of patients with only lymph node metastases without visceral metastasis who received chemoradiotherapy could explain the high response rates in our study groups.

The current study was a small clinical phase II study for patients with advanced TCC who were pretreated with G/C in a single institute. However, paclitaxel with cisplatin appears to be a relatively promising regimen for patients with urothelial TCC who were pretreated with G/C. Therefore, salvage chemotherapy with paclitaxel and cisplatin may be considered in these patients, and further clinical trials are definitely warranted.

References

- 1.Vaughn DJ. Paclitaxel and carboplatin in bladder cancer: recent developments. Eur J Cancer. 2000;36(Suppl 2):7–12. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(00)00076-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bajorin DF, Dodd PM, Mazumdar M, Fazzari M, McCaffrey JA, Scher HI, Herr H, Higgins G, Boyle MG. Long-term survival in metastatic transitional-cell carcinoma and prognostic factors predicting outcome of therapy. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:3173–3181. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.10.3173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bellmunt J, Albanell J, Paz-Ares L, Climent MA, Gonzalez-Larriba JL, Carles J, de la Cruz JJ, Guillem V, Diaz-Rubio E, Cortes-Funes H, et al. Pretreatment prognostic factors for survival in patients with advanced urothelial tumors treated in a phase I/II trial with paclitaxel, cisplatin, and gemcitabine. Cancer. 2002;95:751–757. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scher HI, Norton L. Chemotherapy for urothelial tract malignancies: breaking the deadlock. Semin Surg Oncol. 1992;8:316–341. doi: 10.1002/ssu.2980080511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sternberg CN, Yagoda A, Scher HI, Watson RC, Geller N, Herr HW, Morse MJ, Sogani PC, Vaughan ED, Bander N, et al. Methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin for advanced transitional cell carcinoma of the urothelium. Efficacy and patterns of response and relapse. Cancer. 1989;64:2448–2458. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19891215)64:12<2448::aid-cncr2820641209>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loehrer PJ, Sr, Einhorn LH, Elson PJ, Crawford ED, Kuebler P, Tannock I, Raghavan D, Stuart-Harris R, Sarosdy MF, Lowe BA, et al. A randomized comparison of cisplatin alone or in combination with methotrexate, vinblastine, and doxorubicin in patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma: a cooperative group study. J Clinoncol. 1992;10:1066–1073. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1992.10.7.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.von der Maase H, Hansen SW, Roberts JT, Dogliotti L, Oliver T, Moore MJ, Bodrogi I, Albers P, Knuth A, Lippert CM, et al. Gemcitabine and cisplatin versus methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin in advanced or metastatic bladder cancer: results of a large, randomized, multinational, multicenter, phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:3068–3077. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.17.3068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Otto T, Bex A, Krege S, Walz PH, Rubben H. Paclitaxel-based second-line therapy for patients with advanced chemotherapy-resistant bladder carcinoma (M1): a clinical phase II study. Cancer. 1997;80:465–470. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19970801)80:3<465::aid-cncr14>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roth BJ, Bajorin DF. Advanced bladder cancer: the need to identify new agents in the post -M-VAC (methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin and cisplatin) world. J Urol. 1995;153:894–900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dreicer R, Gustin DM, See WA, Williams RD. Paclitaxel in advanced urothelial carcinoma: its role in patients with renal insufficiency and as salvage therapy. J Urol. 1996;156:1606–1608. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)65459-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenberg JE, Carroll PR, Small EJ. Update on chemotherapy for advanced bladder cancer. J Urol. 2005;174:14–20. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000162039.38023.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roth BJ, Dreicer R, Einhorn LH, Neuberg D, Johnson DH, Smith JL, Hudes GR, Schultz SM, Loehrer PJ. Significant activity of paclitaxel in advanced transitional-cell carcinoma of the urothelium: a phase II trial of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:2264–2270. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.11.2264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vaughn DJ, Broome CM, Hussain M, Gutheil JC, Markowitz AB. Phase II trial of weekly paclitaxel in patients with previously treated advanced urothelial cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:937–940. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.4.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sternberg CN. Second-line treatment of advanced transitional cell carcinoma of the urothelial tract. Curr Opin Urol. 2001;11:523–529. doi: 10.1097/00042307-200109000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pectasides D, Glotsos J, Bountouroglou N, Kouloubinis A, Mitakidis N, Karvounis N, Ziras N, Athanassiou A. Weekly chemotherapy with docetaxel, gemcitabine and cisplatin in advanced transitional cell urothelial cancer: a phase II trial. Ann Oncol. 2002;13:243–250. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Logothetis CJ, Dexeus FH, Finn L, Sella A, Amato RJ, Ayala AG, Kilbourn RG. A prospective randomized trial comparing MVAC and CISCA chemotherapy for patients with metastatic urothelial tumors. J Clin Oncol. 1990;8:1050–1055. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1990.8.6.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pycha A, Grbovic M, Posch B, Schnack B, Haitel A, Heinz-Peer G, Zielinski CC, Marberger M. Paclitaxel and carboplatin in patients with metastatic transitional cell cancer of the urinary tract. Urology. 1999;53:510–515. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(98)00543-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Culine S. The present and future of combination chemotherapy in bladder cancer. Semin Oncol. 2002;29:32–39. doi: 10.1053/sonc.2002.34271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.von der Maase H, Sengelov L, Roberts JT, Ricci S, Dogliotti L, Oliver T, Moore MJ, Zimmermann A, Arning M. Long-term survival results of a randomized trial comparing gemcitabine plus cisplatin, with methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, plus cisplatin in patients with bladder cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4602–4608. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kattan J, Culine S, Theodore C, Droz JP. Phase II trial of ifosfamide, fluorouracil, and folinic acid (FIFO regimen) in relapsed and refractory urothelial cancer. Cancer Invest. 1995;13:276–279. doi: 10.3109/07357909509094462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCaffrey JA, Hilton S, Mazumdar M, Sadan S, Kelly WK, Scher HI, Bajorin DF. Phase II trial of docetaxel in patients with advanced or metastatic transitional-cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:1853–1857. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.5.1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pagliaro LC, Millikan RE, Tu SM, Williams D, Daliani D, Papandreou CN, Logothetis CJ. Cisplatin, gemcitabine, and ifosfamide as weekly therapy: a feasibility and phase II study of salvage treatment for advanced transitional-cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2965–2970. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.11.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vaishampayan UN, Faulkner JR, Small EJ, Redman BG, Keiser WL, Petrylak DP, Crawford ED. Phase II trial of carboplatin and paclitaxel in cisplatin-pretreated advanced transitional cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;104:1627–1632. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bellmunt J, Ribas A, Eres N, Albanell J, Almanza C, Bermejo B, Sole LA, Baselga J. Carboplatin-based versus cisplatin-based chemotherapy in the treatment of surgically incurable advanced bladder carcinoma. Cancer. 1997;80:1966–1972. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19971115)80:10<1966::aid-cncr14>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petrioli R, Frediani B, Manganelli A, Barbanti G, De Capua B, De Lauretis A, Salvestrini F, Mondillo S, Francini G. Comparison between a cisplatin-containing regimen and a carboplatin-containing regimen for recurrent or metastatic bladder cancer patients. A randomized phase II study. Cancer. 1996;77:344–351. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960115)77:2<344::AID-CNCR18>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]