Abstract

Objectives. Parks provide places for people to experience nature, engage in physical activity, and relax. We studied how residents in low-income, minority communities use public, urban neighborhood parks and how parks contribute to physical activity.

Methods. In 8 public parks, we used direct observation to document the number, gender, race/ethnicity, age group, and activity level of park users 4 times per day, 7 days per week. We also interviewed 713 park users and 605 area residents living within 2 miles of each park.

Results. On average, over 2000 individuals were counted in each park, and about two thirds were sedentary when observed. More males than females used the parks, and males were twice as likely to be vigorously active. Interviewees identified the park as the most common place they exercised. Both park use and exercise levels of individuals were predicted by proximity of their residence to the park.

Conclusions. Public parks are critical resources for physical activity in minority communities. Because residential proximity is strongly associated with physical activity and park use, the number and location of parks are currently insufficient to serve local populations well.

Given the growing consensus that the environment plays a key role in promoting energy expenditure,1–3 expanding opportunities to increase physical activity is a promising means of addressing sedentary behaviors associated with a variety of chronic illness.4,5 Fewer than half of all Americans regularly engage in health-protective physical activity.6,7 Increasing population-level physical activity could require substantial changes in our everyday environment.8

Public parks may have an important role to play in facilitating physical activity.9,10 They provide places for individuals to walk or jog, and many have specific facilities for sports, exercise, and other vigorous activities. Nearly 80% of Americans make use of services provided by local recreation departments,11 but parks are often used for purposes other than physical activity.12–14 Fredric Olmstead, the “father” of urban parks, thought parks should be built as places where city residents could experience the beauty of nature, breathe fresh air, and have a place for “receptive” recreation (music and art appreciation) as well as “exertive” activities (sports as well as games like chess).15 Parks are also places where people can socialize with friends and neighbors. In other words, parks can play a role in facilitating physical activity, but do not necessarily do so; indeed, parks also provide opportunities for people to engage in sedentary behavior. Information on who uses public parks and what they do there can elucidate the current and potential contribution of parks to physical activity.14

In studies of neighborhoods in Australia, Giles-Corti et al. found that walking was associated with access to attractive, large, public open spaces,16 and respondents used recreational facilities located near their homes more than facilities located elsewhere. Owen et al.17 reviewed 18 studies and found many environmental features, such as aesthetics and the presence of hills, were associated with self-reported physical activity, although none of those studies objectively examined what activity occurs in parks and open spaces.

To what extent do parks play a role in reducing sedentary behavior, and what characteristics of parks are most important for physical activity? Approximately 30 years ago, the National Parks and Recreation Association (NPRA) established a standard of 10 acres per 1000 people to be devoted to parks and recreational spaces.18 However, many localities could not achieve this standard, given the cost and limited availability of land. In 1996, the NPRA backed away from this size recommendation, saying “in deference to . . . differing geographical, cultural, social, economic, and environmental characteristics, each community must select a level of service guideline which they can live with in terms of their community setting.”18(p48)

Features other than size may influence park use, including accessibility, availability, and quality of amenities. Use is also likely a reflection of individual preferences, as well as age, exercise habits, and race/ethnicity.12,13 Other important characteristics include surrounding land use and availability of organized events that draw people to the park.19 In a review article, Godbey et al.10 emphasized the need to include objective measures of physical activity when studying parks. In this study, we used several methods, including direct observation, to examine how 8 parks in minority communities in the City of Los Angeles were used, and how much physical activity occurs in them. We also explored how services might be changed to better serve residents.

METHODS

Park Selection

We chose 8 parks located in neighborhoods within the City of Los Angeles with residents of similar ethnic and economic distribution and observed them between December 2003 and May 2004. Four parks were designated by the city to receive significant improvements (e.g., new or improved gymnasiums) and 4 were similar in size and facilities and were not to be improved in the next few years. All park census tracts had a high percentage of minorities (Latino [range, 11%–95%], African American [range, 0%–88%]), and 6 had high household poverty (mean = 35%; range, 16–55) compared with the national percentage. The number of people living within 1 mile of these parks’ street boundaries varied between 24 778 and 75 292, equaling a population density between 8000 and 23 000 people per square mile (Table 1 ▶).

TABLE 1—

Demographic Description of Parks and Surrounding Neighborhoods: Los Angeles, Calif, December 2003–May 2004

| Population | Race/Ethnicity | ||||||||

| Park | Acres | In 0.5-Mile Radius | In 1-Mile Radius | In 2-Mile Radius | African American, % | White, % | Latino, % | Households in Poverty (%) | % Aged Older Than 60 Yearsa |

| 1 | 16.0 | 17 175 | 63 457 | 207 984 | 31.0 | 1.6 | 65.1 | 43.6 | 6.0 |

| 2 | 9.0 | 16 994 | 63 404 | 227 757 | 34.3 | 0.0 | 65.0 | 31.3 | 9.5 |

| 3 | 3.4 | 11 569 | 25 441 | 100 412 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 95.4 | 47.3 | 8.7 |

| 4 | 4.2 | 9930 | 44 197 | 155 183 | 1.7 | 5.0 | 80.3 | 30.6 | 16.9 |

| 5 | 8.5 | 9542 | 39 816 | 171 877 | 87.5 | 0.5 | 11.3 | 13.8 | 21.6 |

| 6 | 8.0 | 8966 | 45 693 | 178 486 | 74.5 | 1.4 | 20.5 | 13.8 | 17.2 |

| 7 | 6.4 | 20 606 | 75 292 | 165 935 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 94.2 | 32.3 | 14.3 |

| 8 | 7.0 | 14 130 | 30 934 | 63 420 | 4.8 | 5.3 | 86.4 | 41.2 | 6.9 |

| Total | 108 912 | 388 234 | 1 271 054 | 31.0 | 1.8 | 63.5 | 30.4 | 12.5 | |

Source. US Census 2000, Summary File 3.20

aOf total population living in the census tract.

Including all other parks in the areas in addition to those studied, the ratio of total park size to people within 1 mile of the 8 parks was 0.65 acres per 1000 people. An average of 159125 people lived within the 2-mile radius, increasing the ratio of park space to people to 0.77 acres per 1000 people. This is less than 10% of prior NPRA recommendations.

Study Design and Data Sources

We collected data using 2 methods: by performing systematic observations and by conducting interviews with both park users and residents living within a 2-mile radius of each park and by using data from the 2000 US Census for race/ethnicity, age, gender, and income.20

Observations

Systematic observations were made using SOPARC (the System for Observing Play and Recreation in Communities; methodology is as follows)21 each day of the week that there was no rain. All potential areas for physical activity (i.e., target areas) were established with respect to location, size, and boundaries by mapping each park. A total of 165 areas were observed (about 20 areas per park), including grassy areas, multipurpose fields, playgrounds, gymnasiums, tennis courts, basketball courts, handball courts, tracks, baseball diamonds, horseshoe pits, spectator stands, gymnastics-equipped areas, picnic areas, and swimming pools. Large grassy and wooded areas, such as those separated by buildings, were divided into smaller areas, so that all people using them could be seen during an observation.

Observations were conducted in all target areas during 4 1-hour time periods beginning at 7:30 am, 12:30 pm, 3:30 pm, and 6:30 pm. Target areas were observed in the same rotational order during each observation period. If the observation rotation took less than 30 min, it was repeated, and the results averaged. Two observers worked together to document the type of activity and each person’s activity level (sedentary, walking, vigorous), gender, age group (child, adolescent, adult, senior), and race/ethnicity (Latino, African American, White, and other). Reliability checks with a third independent observer indicated that the procedure had good reproducibility, with agreement between independent observers being greater than 0.8 for person-related variables and greater than 0.9 for area-related variables.21

During each visit to a target area, observers documented whether it was dark, accessible, usable, provided with supervision or equipment (e.g., balls for activity), and if the activity was organized (e.g., activity lessons, sports games). Assessors coded all people in each target area at the moment of observation. People leaving the area before the observation or entering afterwards were not counted. In some instances, people may have moved into a second target area during the observation rotation and were counted twice. Similarly, people sedentary at the moment of observation (e.g., standing while playing basketball) were coded so, even if they previously or subsequently walked or ran.

One park had a usable running track. We determined the amount of time it took to walk around the length of the area (10 min). At a specified coding station, we observed everyone who came by during this time interval.

Energy expenditure at a park is a combination of the intensity of activities occurring and the number of people engaging in them. We estimated the energy expended by using METs, an abbreviation for “metabolic,” but a term that represents the ratio of working metabolic rate to standard resting metabolic rate. We assigned the level of METs as 1.5 for sedentary, 3 for walking, and 6 for vigorous activity, as listed by Ainsworth et al.22

Surveys

We conducted face-to-face interviews in either English or Spanish with both park users (n = 713) and neighborhood residents (n = 605). Only persons over 18 years of age were eligible. At parks, respondents were recruited by field staff between observations (7:30 am–1:30 pm and 1:30 pm–7:30 pm). Participants were selected from the busiest and least-busy target areas, and half in each target area were selected because they were sedentary, and half because they were active. We viewed target areas by scanning across them from left to right. Scans for identifying respondents were done systematically, by selecting the first person on the left in the field of vision of the observers.

Household interviews were done by randomly choosing a sample of addresses within a 0.25-mile-radius of the park, and within 0.25 to 0.5 mile, 0.5 to 1 mile, and 1 mile to 2 miles from the park. We used ArcView (Environmental Systems Research Institute, Inc, Redlands, CA) software to select all possible addresses in these buffers and then randomly selected 20 addresses in each stratum. Field staff followed a protocol to replace addresses if a household did not exist or appeared dangerous because of dogs, gates, or gang activity.

Using the survey data from residents, we used SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) to develop a multivariate model predicting both frequency of park visits and frequency of exercise. Independent variables included age, gender, race/ethnicity, proximity to the park, and perceptions of park safety, park characteristics, and performance of park staff. To predict whether residents used the park once each week or more often versus less than once per week, we fit the data to a multivariate logistic regression equation. We analyzed the frequency of weekly leisure exercise as the number of the times per week a person exercises. Because data were positively skewed and overdispersed, we modeled this outcome variable with the negative binomial distribution.

RESULTS

Park Facilities and Activities

All 8 parks were public, urban, neighborhood parks, and each had a recreation center consisting of a building with an office and classrooms. All had outdoor basketball courts, field areas, and playgrounds. Seven had gymnasiums, 4 had tennis courts, and 6 had picnic areas. Two parks had running tracks, but only 1 was accessible, because the other was behind a locked fence. Some parks provided programming, such as after-school events for children and adolescents, daytime childcare programs, and team sports, such as soccer, basketball, or baseball, depending on the season. Supervised activities occurred primarily in 4 area types: gymnasiums, basketball courts, multipurpose fields, and baseball and softball fields.

Observed Park Use

We observed an average of 1849 persons per week using each park (range, 524–4628). This represented 1.1%–6.7% of the population within a 1-mile radius and 0.37%–3% of the population within a 2-mile radius. More males were seen in parks than females (62% vs 38%), and they outnumbered females in all park areas except playgrounds and the track, where the numbers were about equal. Fewer than 5% of park users appeared to be over 60 years of age; 33% were children, 19% were adolescents, and 43% were adults. Compared with their distribution in the census population, adolescents were seen in proportionately greater numbers, and seniors (over 60 years of age) were seen the least.

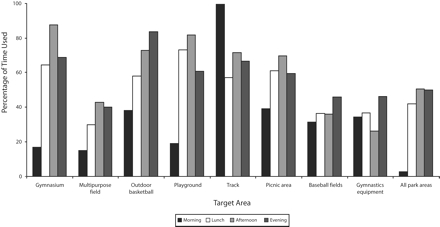

The most common activities coded were sitting or picnicking (22%), followed by playing basketball (15%), being a spectator of organized sports (13%), playing soccer (9%), and using the playground (8%). There were many time periods during which park areas went unused. Target areas were empty 57% of the time we observed them. Most facilities were less used in the mornings, with the exception of the track (Figure 1 ▶).

FIGURE 1—

Average percentage of time target area is used each day: 8 public, urban, neighborhood parks, Los Angeles, Calif, December 2003–May 2004.

Of all park users, 66% were sedentary (range by park, 49%–77%), 19% were walking (range, 12%–30%), and 16% were engaged in vigorous activity (range, 11%–23%). People were more likely to be engaged in walking and vigorous activity in the multipurpose fields (34%), volleyball courts (33%), tennis courts (32%), and basketball courts (31%) and playgrounds (26%). In general, males were nearly twice as likely to engage in vigorous activity as females (19% vs 10%).

Energy Expenditure and Park Use

The number of users in similar parks varied, ranging from 524 to 4628 individuals overall. Estimated MET values per park user varied by 32% (METs, 2.2–2.9; P<.001). When adjusting for the population living within 1 mile of the park, MET expenditure varied by over 5-fold (0.03 vs 0.17; P<.001). Parks drawing the most people tended to account for more energy expended (see Table 2 ▶).

TABLE 2—

Comparison of Neighborhood Park Characteristics, Including Number of Persons Observed, Energy Expenditure per Person, and Population Served: Los Angeles, Calif, December 2003–May 2004

| Park | Facilities Not Present | Extra Facilities | No. of People Observed | Neighborhood Population Observed, % | Areas Being Supervised, %a | Total METs | Mean Observed METs per Person Observed | Total Population Living Within 1-Mile Radius (no.) | METs per Person Living Within 1-Mile Radius |

| 1 | Handball, track (but locked) | 2491 | 3.9 | 13 | 6990 | 2.8 | 63 457 | 0.11 | |

| 2 | Handball | 1290 | 2.0 | 9 | 3129 | 2.4 | 63 404 | 0.05 | |

| 3 | Tennis | 993 | 3.9 | 15 | 2711 | 2.7 | 25 441 | 0.01 | |

| 4 | Auditorium, indoor gym, tennis | 1020 | 2.3 | 5 | 2273 | 2.2 | 44 197 | 0.05 | |

| 5 | Track | 1760 | 4.4 | 13 | 4390 | 2.5 | 39 816 | 0.11 | |

| 6 | 524 | 1.1 | 7 | 1524 | 2.9 | 45 693 | 0.03 | ||

| 7 | Tennis | 4628 | 6.1 | 30 | 10 094 | 2.2 | 75 292 | 0.17 | |

| 8 | Tennis | Landscaped skate park | 2085 | 6.7 | 4 | 5201 | 2.5 | 30 934 | 0.13 |

| Total (mean) | 14 791 | 3.8b | 9b | 36 311 | 2.5b | 388 234 | 0.10a |

Note. MET = ratio of working metabolic rate to standard resting metabolic rate.

aSupervision could be by anyone, including parents, coaches and so on.

b Mean

Organized sports occurred during 9% of observations. Of these, 25% were in gymnasiums, 7% on baseball diamonds, 5% on soccer fields, and 2% on outdoor basketball courts. On average, more people were present during supervised activities (e.g., sports competitions) than unstructured activities (49 vs 6 people; P < .006). The correlation between the percent of areas being supervised and the total METs estimated for each park was 0.74 (P < .04).

Self-Reported Park Use

The 2 interview groups, park users and residents living within a 2-mile radius of the park, were similar in race/ethnicity (74% Latino, 24% African American). The average age was 38 years (SD= 13; range, 18–90), but park respondents were younger than residents (36 vs 39; P < .001) and more likely to be men (63% vs 50%; P < .001). The response rate was 63% among park users and 88% among residents.

More park users than neighborhood residents reported visiting the park at least a few times per week (71% vs 34%; P < .001). Both groups named the park as the most common place for exercise, and only 6% of residents and 3% of park users reported using a health club for exercise. A total of 86% of residents visited the targeted park monthly or more often; 35% never went to other parks.

The most common park activity among both residents and park users was sitting (72%), followed by walking (59% of park users vs 65% of residents; P = .07), using the playground (40%), having a party or celebrating (26%), and meeting friends (20%). The most common sport people played in the park was basketball (25%), followed by soccer (9%) and baseball (6%).

The top 5 suggestions among residents and park users for improving their local park were: provide more park events and fairs (48%), improve landscaping (42%), more adult sports (39%), more and improved walking paths (38%), and more youth sports (37%).

Perception of Safety and Park Staff Performance

Most respondents (71% of residents and 75% of park users) said they felt safe in the parks, but this varied considerably by park. Nearly all respondents (98%) living near the 2 parks with the lowest percentage of households in poverty indicated that they felt the parks were safe, compared with between 50% and 74% for parks in neighborhoods with over 40% of households in poverty. There were no differences in perception of safety between men and women residents, between residents and park users, or among adult age groups. When asked what park features they would like to see improved, 19% identified concerns about safety in their top 5 requests.

When asked to rate park staff, 35% could not comment because they never interacted with staff; however, 92% of those who had gave staff a grade of “A” or “B.”

Distance Traveled to Visit the Park

People living closer to the park tended to visit more often. Among observed park users, 43% lived within 0.25 mile, and another 21% lived between 0.25 and 0.5 mile of the park (P < .001). Only 13% of park users lived more than 1 mile from the park. Of local residents, 38% living more than 1 mile away were infrequent park visitors, compared with 19% of those living less than 0.5 mile away (P < .001). Residents who visited the park monthly or more frequently lived an average of 0.7 miles away versus 1.07 miles for those visiting less frequently.

Proximity was not only associated with frequency of park visits but also with self-reported leisure exercise. More residents living within 0.5 miles of the park reported leisurely exercising 5 or more times per week more often than those living more than 1 mile away (49% vs 35%; P < .01).

Predictors of Park Use and Exercise

Table 3 ▶ shows a logistic regression model predicting park use. Table 4 ▶ presents the incidence rate ratios predicting leisure exercise in a park. In both models, we found that age (being younger), gender (being male), and distance (living within 1 mile of a park) were positively associated with park use and the frequency of leisure exercise. People who lived within 1 mile of the park were 4 times as likely to visit the park once a week or more and had an average of 38% more exercise sessions per week than those living further away. Concerns about park safety were not associated with either park use or frequency of exercise.

TABLE 3—

Logistic Regression Predicting Neighborhood Park Use by Area Residents (n=467): Los Angeles, Calif, December 2003–May 2004

| Prediction of Park Use,a OR (95% CI) | |

| Residential distance to park | |

| > 1 mile | (Reference) |

| ≥ 1 mile to park | 4.21* (2.54, 7.00) |

| Age (18–84 y) | 0.98** (0.97, 0.999) |

| Gender (male = 1) | 1.56** (1.04, 2.34) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| Latino | (Reference) |

| African American | 0.83 (0.46, 1.48) |

| Other/Asian/White | 0.34 (0.05, 2.27) |

| Indicator of safety (safe = 1) | 0.94 (0.56, 1.57) |

| Parkb | |

| 1 | (Reference) |

| 3 | 0.74 (0.35, 1.59) |

| 4 | 0.44*** (0.22, 0.88) |

| 5 | 1.69 (0.80, 3.55) |

| 6 | 0.64 (0.34, 1.26) |

| 7 | 2.65*** (1.29, 5.44) |

| 8 | 0.71 (0.27, 1.84) |

Note: CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio.

aVisiting the park once per week or more.

bThe distance residents lived from Park 2 was not available, therefore Park 2 was not included in the sample.

* P< .001; ** P < .05; *** P < .01.

TABLE 4—

Negative Binomial Regression Predicting Exercise Sessions per Week for Area Residents (n = 373): Los Angeles, Calif, December, 2003–May, 2004

| Prediction of Exercise Sessions,a IRR (95% CI) | |

| Residential distance to park | |

| > 1 mile | (Reference) |

| ≥ 1 mile | 1.38* (1.04, 1.84) |

| Age (18–84 y) | 0.98** (0.97, 0.99) |

| Gender (male = 1) | 1.28* (1.01, 1.62) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Latino | (Reference) |

| African American | 1.12 (0.84, 1.50) |

| Other/Asian/White | 1.25 (0.80, 1.94) |

| Indicator of safety (safe = 1) | 0.93 (0.67, 1.28) |

| Parkb | |

| 3 | 0.91 (0.60, 1.39) |

| 4 | 0.85 (0.55, 1.33) |

| 5 | 1.25 (0.94, 1.66) |

| 6 | (Reference) |

| 7 | 1.20 (0.71, 2.00) |

| 8 | 0.95 (0.66, 1.38) |

Note: IRR = incidence rate ratio; CI = confidence interval.

aIncreases in area residents’ exercise sessions per week.

bSurvey respondents of Parks 1 and 2 were not asked about the number of exercise sessions per week, so they were not included in the sample.

* P < .001; ** P < .05.

DISCUSSION

Parks play a critical role in facilitating physical activity in minority communities,10,13,14 not only by providing facilities and scheduled, supervised activities, but also by providing destinations to which people can walk—even though they may be sedentary after arriving there. Most people who exercised did so in their local park, so the frequency of exercise and frequency of park use are both associated with park proximity. Although not all people living close to parks used them, many more living farther away did not do so because of distance.

These findings suggest that communities should be designed so that all people have a park within at least 1 mile of their residence. Our observation data showed that more people used specific areas when they were provided organized activities, suggesting that increasing the availability of structured, supervised activities will also likely increase park use; however, only 9% of all observations found areas supervised, suggesting that greater attention should be paid to staffing. Parks serving similar populations had vastly different energy expenditures when providing different types of organized activities, suggesting that park management and physical activity opportunity variables are important to park use.

Perceptions of safety may affect the use of recreational areas,21 but they did not predict park use in this study. Our analysis, however, was restricted to 8 parks, mostly in low-income, minority neighborhoods. A larger sample of parks with greater variation might provide different results.

Despite a general increasing emphasis of physical activity among girls and mandates of Title IX,23 which in 1972 banned gender discrimination in academics and athletics in any institution receiving federal aid, we observed large disparities in park use between boys and girls in both organized and nonorganized activities. It is unlikely that perceptions of safety account for this difference, because differences in park safety perception did not exist by gender among the sample of interviewed residents. Playgrounds, jogging paths, and tennis courts were used at similar rates by men and women, but areas primarily used for competitive team sports were dominated by men. When women did go to the park, they were more likely to be in areas like playgrounds, where they could supervise children, rather than on basketball courts and soccer fields, where they could engage in vigorous exercise themselves. Providing women with opportunities for exercise while simultaneously supplying other sources of care for their young children will likely be necessary to close the gender gap in physical activity. Alternatively, providing more facilities, such as tracks and walking paths, may also be useful.

Few seniors used the parks; however, the presence of senior citizen centers on the park premises was associated with higher numbers of older individuals observed in the park. This suggests that seniors may need special programs or incentives to use park facilities. However, the 1 park with a track appeared to draw a large proportion of older individuals. Whether track facilities draw older people, or whether this was an anomaly, needs to be further examined.

These 8 parks served thousands of individuals each week. Considering the amount of time their facilities were not used, however, parks could have an even greater impact on the population. Facilities were largely unused during large segments of every week, especially in the mornings. Had local residents maximized the use of parks for exercise, we would have observed many more park users than we did. If only 55% of the population living within 1 mile of a park used it for 30 min of exercise daily, we would expect to see an average of 1110 people in each park every daylight hour. These neighborhood parks, however, do not have the capacity to serve such a high volume of people. Clearly, the current configuration of parks cannot meet the physical activity needs of all the population; nonetheless, they have the capacity to serve a great many more individuals than they currently do. Although increasing and improving facilities would likely increase park use, the greatest gains in serving more people might come from increasing the number of events and organized activities scheduled in parks. Meeting this objective would require the hiring and training of more personnel, including coaches, activity supervisors, and event planners.

Our study was limited in that we observed parks and interviewed residents and park users for only 56 days. These days may not be representative of total park use and physical activity, and may not capture secular variations. Our estimates, however, provide a snapshot of park use by age, race/ethnicity, gender, and activity level. The primary finding that residential proximity to a park was the most robust predictor of both park use and self-reported leisure exercise in urban, minority communities should be noted by urban planners and officials responsible for ensuring safe and healthy neighborhoods. Facilitating larger numbers of people being physically active is critical for improving overall population health.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Institute of Environmental Health Services (grant P50ES012383-03).

We thank Kristen Leuschner for her helpful comments on earlier versions of the manuscript. We also thank Luis Mata, Rosa Lara, and the promotoras of the Multi-Cultural Area Health Education Center and the Los Angeles City Department of Recreation and Parks for their assistance with questionnaire development and data collection.

Human Participant Protection This study was reviewed and approved by the RAND human subjects protection committee.

Peer Reviewed

Contributors D. Cohen originated the study and supervised all aspects of implementation. T. L. McKenzie assisted in staff training, data analysis, and article preparation. A. Sehgal trained field staff, supervised the data collection, and conducted reliability checks. S. Williamson and D. Golinelli analyzed the data and assisted with the study. N. Lurie helped plan the study. All authors helped to conceptualize ideas, interpret findings, and review drafts of the article.

References

- 1.Saelens BE, Sallis JF, Frank LD. Environmental correlates of walking and cycling: findings from the transportation, urban design, and planning literatures. Ann Behav Med. 2003;25:80–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sallis JF, Conway TL, Prochaska JJ, McKenzie TL, Marshall SJ, Brown M. The association of school environments with youth physical activity. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:618–620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sallis JF, McKenzie TL, Conway TL, et al. Environmental interventions for eating and physical activity: a randomized controlled trial in middle schools. Am J Prev Med. 2003;24:209–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersen LB, Schnohr P, Schroll M, Hein HO. All-cause mortality associated with physical activity during leisure time, work, sports, and cycling to work. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1621–1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldbourt U. Physical activity, long-term CHD mortality and longevity: a review of studies over the last 30 years. World Rev Nutr Diet. 1997;82:229–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Office of the Surgeon General. Overweight and Obesity: The Surgeon General’s Call To Action To Prevent and Decrease Overweight and Obesity. Rockville, Md: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2001. [PubMed]

- 7.Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System: Risk factor for meeting recommended guidelines for vigorous physical activity. Atlanta, Ga: US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2003.

- 8.Sallis JF, Bauman MP. Environmental and policy interventions to promote physical activity. Am J Prev Med. 1998;15:379–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bedimo-Rung AL, Mowen AJ, Cohen D. The significance of parks to physical activity and public health: a conceptual model. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28(suppl 2): 159–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Godbey GC, Caldwell LL, Floyd M, Payne LL. Contributions of leisure studies and recreation and park management research to the active living agenda. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28(suppl 2):150–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Godbey GC, Graefe A, James, SW. The Benefits of Local Recreation and Park Services: a Nationwide Study of the Perceptions of the American Public. Ashburn, Va: National Recreation and Park Association; 1992.

- 12.Gobster P. Managing urban parks for a racially and ethnically diverse clientele. Leisure Sci. 2002;24:143–159. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tinsley H, Tinsley D, Croskeys C. Park usage, social milieu, and psychosocial benefits of park use reported by older urban park users from four ethnic groups. Leisure Sci. 2002;24:199–218. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walker C. The public value of urban parks. In: Beyond Recreation: a Broader View of Urban Parks. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute; 2004.

- 15.Olmstead F. Public parks and the enlargement of towns. In: LeGates RT, Stout F, eds. The City Reader. 2nd ed. London: Routledge; 1999:314–320.

- 16.Giles-Corti B, Broomhall MH, Knuiman M, et al. Increasing walking: how important is distance to, attractiveness, and size of public open space? Am J Prev Med. 2005;28(suppl 2):169–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Owen N, Humpel N, Leslie E, Bauman A, Sallis JF. Understanding environmental influences on walking: review and research agenda. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27: 67–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mertes J, Hall J. Park, Recreation, Open Space and Greenway Guidelines. Ashburn, Va: National Recreation and Park Association; 1996.

- 19.Jacobs J. The uses of neighborhood parks. In: The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York, NY: Modern Library; 1961:116–145.

- 20.US Census 2000. Summary File 3, Population and Housing. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2003. Available at: http://www.census.gov/main/www/cen2000.html. Accessed December 1, 2003.

- 21.McKenzie TL, Cohen DA, Sehgal A, Williamson S, Golinelli D. System for Observing Play and Leisure Activity in Communities (SOPARC): reliability and feasibility measures. J Phys Activity Health. 2006;3(suppl 1): S208–S222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Whitt MC, et al. Compendium of physical activities: an update of activity codes and MET intensities. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32(suppl 9):S498–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.United States Department of Labor. Title IX, Education Amendment of 1972. Available at: http://www.dol.gov/oasam/regs/statutes/2000e-16.htm. Accessed January 31, 2007.