Abstract

Skill improvements may develop between practice sessions during memory consolidation. Skill enhancement within an egocentric coordinate frame develops over wake, whereas skill enhancement in an allocentric coordinate frame develops over a night of sleep. We tested whether both types of improvement could develop over two different 24-hr intervals: 8am to 8am or from 8pm to 8pm. We found that for each 24 hour interval, only one type of skill improvement was seen. Despite passing through wake and a night of sleep participants only showed skill improvements commensurate with either a night of sleep or a day awake. The nature of the off-line skill enhancement was determined by when consolidation occurred within the normal sleep-wake cycle. We conclude that motor sequence consolidation is constrained either by having critical time windows or by a competitive interaction in which improvements within one coordinate frame actively block improvements from developing in the alternative coordinate frame.

Introduction

Skill learning tasks can be refracted into multiple components. Each of these components is encoded within distinct neural circuits (Hikosaka et al. 1999; Hikosaka et al. 2002). A particularly vivid example of this is provided by the distinction between information represented within allocentric co-ordinates – in which the location of objects are coded in relation on one another - or egocentric co-ordinates - in which object location is centred around the body. For example, humans learn to navigate a new route as a series of turns (egocentric co-ordinates) plus as a series of key landmarks within the landscape (allocentric co-ordinates, (Vidal et al. 2004)). Similarly, learning to make reaching movements within a visually distorted environment requires changes within egocentric plus allocentric co-ordinates (Hatada et al. 2006; Lee and van Donkelaar 2006). Improved performance during learning is supported by the encoding of skill within both co-ordinate frames.

During consolidation however, skill components are differentially processed: skill represented in an egocentric coordinate frame is enhanced over wake, whereas skill represented in an allocentric coordinate frame is enhanced over a night of sleep (Cohen et al. 2005). A 24-hr interval containing a normal sleep-wake cycle may support the development of improvements within both the egocentric and allocentric co-ordinate frames. Alternatively, only one type of improvement – either within an allocentric or egocentric co-ordinate frame - might develop over a 24-hr interval. This result would suggest that when consolidation takes place within a 24 hour sleep-wake cycle determines the nature of the off-line skill enhancement.

In this study, we isolated the egocentric and allocentric skill components in a procedural learning task - the serial reaction time task (SRTT). In this task, a visual cue can appear at any one of four positions arranged horizontally on a computer screen (Nissen and Bullemer 1987). Each screen position corresponds to a button on a response box. When a cue appears, a participant selects the corresponding button, and after a short fixed delay, another cue is presented. Unbeknownst to the participants, the positions of the cues follow a repetitive order. This sequence is learnt simultaneously as a series of spatial goals in allocentric coordinates, referred to as goal-based skill, and as a series of finger movements in egocentric coordinates, referred to as movement-based skill (Willingham 1999).

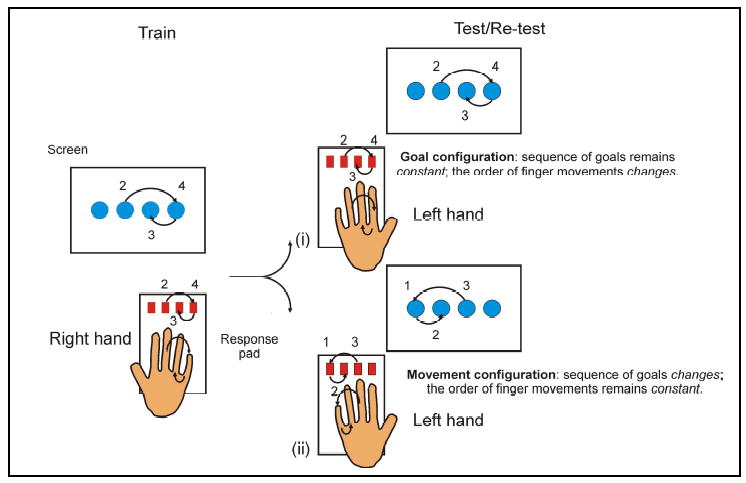

After training with one hand, the goal and movement-based components can be distinguished by probing skill with the untrained hand (Figure 1, (Hikosaka et al. 1999 ; Grafton et al. 2002; Japikse et al. 2003; Verwey and Wright 2004; Verwey and Clegg 2005)). By switching from the right to the left hand, the same finger is no longer associated with the same response. So, although the same sequence of response buttons is required, this goal is achieved using a different set of finger movements. For example, a triplet -2-4-3- is first performed with the –middle-little-ring- of the right hand and then with the –ring-index-middle- of the left hand. Thus the goal remains the same (i.e. -2-4-3-) but the order of finger movements changes (from –middle-little-ring- to –ring-index-middle-). Alternatively, it is possible to preserve the order of finger movements but change the sequence of response buttons (Figure 1). For example, a triplet may change from being -2-4-3- with the right hand to being -3-1-2- with the left hand so that the order of finger movements remains unchanged as: –middle-little-ring-. Thus the goal of the movements is altered (from -2-4-3- to -3-1-2- ) but the order of finger movements, albeit of the opposite hand, is preserved. These manipulations generate two task configurations: the first (goal-configuration) probes goal-based learning and the other (movement-configuration) probes movement-based learning.

Figure 1.

In the SRT task, visual cues are presented on a screen and guide procedural learning. Switching hands allows the goal and movement-based components of the learnt skill to be measured. Maintaining the goal (e.g., -2-4-3) but altering the order of finger movements (goal configuration) measures the skill derived from knowledge of the spatial goal (i.e. knowledge of response locations in allocentric coordinates). This has alternatively been called effector-independent skill (Hikosaka et al. 2002). Maintaining the order of finger movements (e.g., -middle-little-ring-) but altering the goal (movement configuration) measures the skill derived from the finger movements (i.e., knowledge of the specific finger movements in egocentric coordinates. This has alternatively been called effector-dependent skill (Hikosaka et al. 2002; Verwey and Wright 2004; Verwey and Clegg 2005). Such a term is a slight misnomer; after all, the skill is assessed by switching hands and so would appear to be independent of the effector or hand used during training. But it is still the same fingers, albeit of the opposite hand (i.e. the homologous fingers, e.g., right index switches to the left index finger), that are performing the movement so it earns the term effector-dependent. This manipulation produces a mirror sequence (e.g., the triplet –2-4-3- is transformed to –3-1-2, (Verwey and Clegg 2005)).

In this experiment, after training with the right (dominant) hand, participants switched to their left hand to be tested (Skill1), and 24-hr later re-tested (Skill2). This allowed goal or movement-based off-line improvements (Skill2 - Skill1) to be measured. By measuring these distinct improvements over two 24-hr intervals (i.e. 8am to 8am vs. 8pm to 8pm), it was possible to determine whether both types of improvement could develop over 24 hours, or whether the type of improvement that developed was determined by when consolidation occurred within the normal sleep-wake cycle. With two interval types (8am to 8am or 8pm to 8pm), and two task configurations (goal or movement), there were four experimental groups.

Methods

Participants

Fifty-four right-hand dominant (defined by the Edinburgh handedness questionnaire (Oldfield 1971) participants were recruited. Off-line improvements can be modified by a participant’s ability to recall segments of the sequence (Robertson et al. 2004). Those reporting four or less items consistently show goal-based improvements over a night of sleep and movement-based improvements over wake (Cohen et al. 2005). We wished to examine the development of both types of improvement over a 24hr interval. Consequently, the fourteen participants who were able to recall more than four items of the sequence were removed from further analysis. Data was analysed from the remaining forty participants (18 male, 20.8±0.4years) who were randomly and equally distributed across the four groups. All participants completed a sleep questionnaire and log. The expression of off-line improvements may be influenced by the time-of-day of retesting. To quantitatively address this issue we contrasted improvements in this study against those which developed over 12-hr intervals in an earlier study (Cohen et al. 2005). Two groups were drawn from the earlier study. In the first, goal-based skill was tested at 8pm and retested at 8am; while in the second group movement-based skill was tested at 8am and retested at 8pm. Each group had ten participants (8 male, 19.9±0.4years), all right-handed, all recalling less than 4-items of the sequence and all performed the goal or movement-based version of the SRTT identical to the one used in the current study and described below.

Experimental Design

Performance in the SRTT was measured prior to and following a 24hr interval. This interval either extended from 8am to 8am or from 8pm to 8pm. The first session consisted of three blocks, two of which constituted training blocks (one short and one long) and a test block. After 24 hr, participants performed another test block. The test block before (Skill1) and after (Skill2) the 24 hour interval was designed to measure either movement or goal-based skill. The skill difference (Skill2 - Skill1) between testing and re-testing gave a measure of off-line learning.

The Serial Reaction Time Task (SRTT)

We used a modified version of the SRTT (Nissen and Bullemer 1987). A solid circular stimulus (diameter 20mm, viewed from approximately 800mm) appeared on a monitor at any one of four possible positions within an equally spaced horizontal array. Each position corresponded to one of the four buttons on a response pad (Cedrus, RB-410). When a target appeared, participants were instructed to respond by pressing the appropriate button. Having made the correct response, the cue on the screen disappeared and was replaced by the next cue after a delay of 400ms. For incorrect responses, the stimulus remained until the correct button was selected. Response time was defined as the interval between presentation of a stimulus and selection of the correct response. The task was introduced to participants as a test of reaction time.

The type of off-line improvement was assessed using two different configurations of the SRTT. After training with their right hand, all participants switched hands, allowing the desired component of skill to be isolated. Goal-based skill was assessed by changing the specific pattern of finger movements – by switching hands - while preserving the sequence (2-3-1-4-3-2-4-1-3-4-2-1) of response locations. Movement based skill was assessed by changing the sequence of response locations (from 4-2-3-1-4-2-1-2-4-3-2-3 to 1-3-2-4-1-3-4-3-1-2-3-2), which – having switched hands -preserved the specific pattern of finger movements learnt during training (Figure 1). These two sequences of response location did not share any common triplets, minimising the potential for goal-based transfer between the sequences and giving an uncontaminated probe for movement-based skill (Figure 1).

Session one consisted of a short training block with fifteen repetitions of a twelve item sequence (180 trials), a longer training block with twenty-five repetitions (300 trials), and a test block with fifteen repetitions (180 trails). Session two consisted of a single test block with fifteen repetitions (180 trials) of the sequence. Each block had a similar structure. For all blocks, fifty random trials preceded and followed the sequential trials. Within these random trials there were no item repeats. Each set of random trials in the training and test blocks were unique. However, the random trials were identical across all groups.

Data Analysis

Only the time taken to make correct responses was included in the analysis. Any response time longer than 2.7 standard deviations (i.e. the top one percentile) from a participant’s mean was removed, as was any response time exceeding 3000ms. A sequence learning score was calculated for each session by subtracting the average response time of the final fifty sequential trials from the average response time of the random trials that immediately followed. Accuracy in the SRT task is not a useful measure of skill, because even with limited experience, error rates are extremely low (<1–2%). Skill before the interval (Skill1) was calculated using the final test block of the first session, and skill after the interval (Skill2) was calculated using the first and only test block of the second session. The difference (Skill2-Skill1) between these learning scores gave a measure of off-line learning. Unpaired t-tests were used to detect any difference in initial goal-based skill between the groups tested at 8am versus 8pm, as well as to detect differences in initial movement-based skill between those tested at 8am versus 8pm. An ANOVA was used to compare the amount of off-line learning across the groups. Unpaired t-tests were used to make planned comparisons between groups. To test for off-line learning within each group, paired t-tests were used to compare Skill1 against Skill2. A mixed repeated measures ANOVA was used to explore the possibility that sequential response times within the retest block showed changes that differed across the four groups. The retest block was divided into three equal sets of sixty trials. An average response time was calculated for each of these sets, giving a measure of change in response time across the re-test block, for each participant in each group.

Results

Sequence-specific skill

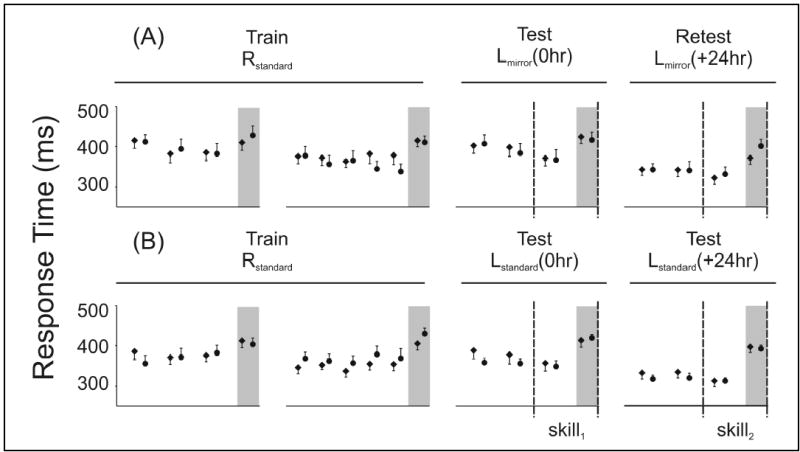

At the end of session one, there was no significant difference in goal based skill between those tested at 8am compared to those tested at 8pm (unpaired t-test, t(18) = 1.71, p = 0.104); likewise, initial movement-based skill did not differ according to the time of initial testing (unpaired t-test, t(18) = 0.52, p = 0.608, Figure 2). Goal and movement based skill were not directly compared because these components may be acquired at different rates (Bapi et al. 2000; Hikosaka et al. 2002).

Figure 2.

Response times averaged over 60 trials, during sequential (white background) and averaged over 50 trials for the random trials (grey columns). During the short and long training blocks all participants responded to a standard sequence using their right hand (Rstandard). Participants then switched to their left hand and either switched to the mirror sequence (Lmirror) to assess (A) movement-based skill or they kept to the standard sequence (Lstandard) to assess (B) goal-based skill. This testing took place at either 8am or 8pm with retesting 24-hrs later (8am to 8am groups are shown by circles; 8pm to 8pm groups are shown by diamonds). Skill at testing (skill1) and retesting (skill2) was the difference between the average response time of the final fifty sequential trials and the following fifty random trials. Movement-based off-line (skill2-skill1) improvements only developed from 8am to 8am (69-50ms = 19ms, c.f. 48–52ms = −4ms); whereas, goal-based improvements only developed from 8pm to 8pm (85-57ms = 28ms, c.f. 76-69ms = 7ms). These differential improvements can not be accounted for by different rates of learning during the retest blocks because changes in sequential response times within the retest block did not vary by group (ANOVA, F(6,29)=0.634, p=0.702).

The aspect of skill that developed over the 24-hr interval between testing and retesting was significantly dependent upon whether the interval extended from 8am to 8am or from 8pm to 8pm (ANOVA, F(1,36) = 11.37, p = 0.002, Figures 2 & 3). Movement-based improvements were significantly greater when the 24-hr interval extended from 8am to 8am than from 8pm to 8pm (unpaired t-test, t(18) = 2.22, p =0.039). In contrast, goal-based improvements were significantly greater when the 24-hr interval extended from 8pm to 8pm than from 8am to 8am (unpaired t-test, t(18) = 2.63, p = 0.017).

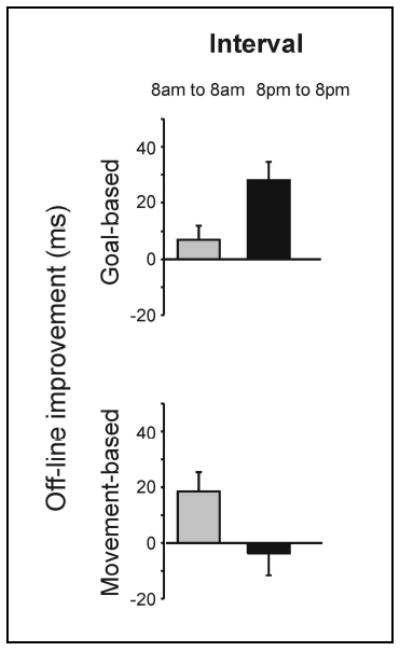

Figure 3.

Over a 24-hr interval, a memory passes through both wake – associated with movement-based improvements and a night of sleep – associated with goal-based improvements (Cohen et al. 2005). Nonetheless, each interval is associated with only one type of skill improvement. Goal-based improvements only developed from 8pm to 8pm; whereas, movement-based improvements only developed from 8am to 8am. Error bars show the standard error of the mean.

Movement-based improvements developed over 24-hr when testing and retesting were at 8am (19±7ms, paired t-test, t(9) = 2.79, p = 0.021); whereas, no significant improvement developed over 24-hr when testing and re-testing were at 8pm (−4±8ms, paired t-test, t(9) = 0.49, p = 0.635, Figure 3). The opposite pattern was observed for goal-based improvements: significant improvements developed over 24-hr when testing and re-testing were at 8pm (28±7ms, paired t-test, t(9) = 4.45, p = 0.002); whereas, no significant improvements were detected when testing and re-testing were at 8am (7±5ms, paired t-test, t(9) = 1.46, p = 0.178, Figure 3).

The expression of goal and movement-based improvements may be affected by when retesting took place: the absence of a significant improvement could reflect the inability to express skill at a particular time of day. This would imply that when contrasting two groups with distinct intervals (e.g. 24-hr vs. 12-hr) there should be: (1) similar improvements when retesting took place at the same time of day (e.g., 8pm) and (2) substantially different improvements when retesting took place at different times of day (e.g., 8pm vs. 8am) for the same skill component (goal or movement). To explore this issue we contrasted the improvements over the 24-hr intervals described here against those which developed over 12-hr intervals described in earlier work (Cohen et al. 2005). There was no significant difference in the goal-based improvements which develop from 8pm to 8am as compared to 8pm to 8pm (unpaired t-test, t(18) = 0.588, p = 0.564). Furthermore, the overnight improvements (8pm to 8am) were significantly greater than those that developed between 8am to 8am in our current study (unpaired t-test, t(18) = 2.559, p = 0.0197). A similar pattern emerged for movement-based improvements: there was no significant difference for improvements previously demonstrated from 8am to 8pm and those that developed between 8am to 8am in the current study (unpaired t-test, t(18) = 0.231, p = 0.820); improvements which developed from 8am to 8pm were significantly greater than those that developed between 8pm to 8pm in the current study (unpaired t-test, t(18) = 2.404, p = 0.027). This demonstrates that goal and movement-based improvements can be observed at either 8am or 8pm; implying that it is unlikely that the time of retesting determined the expression of off-line skill improvements

Response times

Response times, for both sequential and random trials, showed a different pattern of change between testing and re-testing depending upon whether or not there was significant off-line learning. There was a parallel decrease in both sequential and random response times for those groups showing no significant off-line improvement. The random response times decreased significantly between testing and re-testing (8am to 8am, goal-configuration, t(9) = 3.27, p = 0.01; 8pm to 8pm, movement-configuration, t(9) = 6.61, p < 0.001). Sequential response times, in these two groups, showed similar decreases (8am to 8am, goal-configuration, t(9) = 4.6, p = 0.001; 8pm to 8pm, movement-configuration, t(9) = 4.8, p < 0.001). A parallel decrease in both random and sequential response times demonstrates a general but not sequence specific performance improvement. This probably reflects participants’ increasing familiarity with the task.

In contrast, those groups showing significant off-line improvements failed to show a significant decrease in the random response times between testing and re-testing (8pm to 8pm; goal-configuration, t(9) = 1.8, p = 0.105, 8am to 8am; movement-configuration, t(9) = 1.31, p = 0.225). Nonetheless, sequential response times in both these groups showed a significant fall between testing and re-testing (8pm to 8pm; goal-configuration, t(9) = 4.1, p = 0.003, 8am to 8am; movement-configuration, t(9) = 2.4, p = 0.039). The failure to show a decrease in random response time can be explained by proactive interference. When random trials are introduced following sequential trials, participants continue to play out the sequence, producing proactive interference from the sequential to the random trials. Such interference is greater when participants have developed greater sequence specific skill, as is the case for those who developed offline skill improvements. This increased proactive interference counteracts the tendency for response times to decrease due to task familiarity and so prevents a decrease in the random response times.

All participants followed a normal sleep-wake cycle; consequently the amount of time participants spent awake following testing differed significantly between those in the 8am to 8am groups compared to those in the 8pm to 8pm groups (t(38)= 35, p<0.001). Those in the 8am to 8am groups remained awake for the rest of the day, retiring to bed on average 15.1±0.2-hrs after testing. In contrast, those in the 8pm to 8pm groups remained awake on average for only 3.5±0.27-hrs after testing. Nonetheless, the amount of time participants in these groups reported being asleep was not significantly influenced by which skill component was measured (ANOVA, F(1.36) = 0.3, p = 0.559). Thus the differential skill improvements over the different 24-hr intervals can not be accounted for by differences in the amount of time slept.

Discussion

Despite passing through a 24-hr interval containing sleep and wake, participants only showed off-line improvements associated with either wake or a night of sleep. When tested and re-tested at 8am participants only showed movement-based improvements – which develop over wake; whereas, when tested and re-tested at 8pm participants only showed goal-based improvements – which develop over a night of sleep. Thus, there are constraints on the types of improvements that can develop offline.

Skill changes between testing and re-testing sessions were not influenced by the time-of-day because these sessions took place at the same time-of-day. Nonetheless, the time of retesting may influence the expression of off-line improvements. However contrasting improvements over a 12-hr interval - shown in an earlier study - against those that developed over the 24-hr intervals of the current study showed that goal and movement-based improvements can be equally expressed at 8am and at 8pm (Cohen et al. 2005). Thus, time-of-day seems unlikely to have influenced the expression of offline learning. Skill was measured, in both sessions, using the left hand. Consequently hand switching, which allowed goal and movement-based skill to be distinguished, was not responsible for skill changes between testing and re-testing. There are perhaps two mechanisms which might explain the pattern of results – only goal or movement-based improvements over any 24-hr interval.

Following skill acquisition, there may only be a short interval during which off-line processing can take place. The duration of this critical time window is not known, but an earlier study has suggested that at least 4–6hr is necessary for significant skill to develop off-line (Press et al. 2005). When a continuous interval of >4-hr is spent awake (i.e., 8am to 8am) movement-based improvements develop; whereas, when overnight sleep (i.e. 8pm to 8pm) allows only 3.5-hr awake then goal-based improvements develop. Previous studies have shown that similar improvements develop provided sleep occurs within a critical time after initial practice (Fischer et al. 2002; Walker et al. 2003). Some procedural memories also remain susceptible to interference for a critical time following acquisition (Brashers-Krug et al. 1996; Muellbacher et al. 2002; Walker et al. 2003). Thus, a critical time window may be a general feature of off-line processing.

Alternatively, there may be a competitive interaction between distinct components of a procedural memory during consolidation. Therefore, the enhancement of one aspect of the memory may prevent the enhancement of another aspect. Competitive interactions between memories are thought to occur during encoding (Poldrack and Packard 2003); they may also occur during consolidation (Schroeder et al. 2002).

These observations demonstrate that off-line motor sequence learning can only occur within a critical time window following initial encoding or that there is a competitive interaction between skill components; with enhancement of one component actively preventing the enhancement of the alternative component. Regardless of the exact mechanism, only improvements associated with either wake or a night of sleep develop; both types of improvement are not observed over a 24-hr interval of sleep and wake.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Kerry Rees for helping to recruit participants to this study, to Matthew Walker for his helpful comments, to Alvaro Pascual-Leone for continued encouragement and to Chris Miall whose thoughtful questions prompted this study. Funding from the National Institutes of Health supported this study: (R01-NS051446, EMR) and DAC was a participant of Harvard Medical School’s Scholars in Clinical Science Program (K30 HL04095).

References

- Bapi RS, Doya K, Harner AM. Evidence for effector independent and dependent representations and their differential time course of acquisition during motor sequence learning. Exp Brain Res. 2000;132:149–162. doi: 10.1007/s002219900332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brashers-Krug T, Shadmehr R, Bizzi E. Consolidation in human motor memory. Nature. 1996;382:252. doi: 10.1038/382252a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen DA, Pascual-Leone A, Press DZ, Robertson EM. Off-line learning of motor skill memory: A double dissociation of goal and movement. PNAS. 2005;102:18237–18241. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506072102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer S, Hallschmid M, Elsner AL, Born J. Sleep forms memory for finger skills. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:11987–11991. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182178199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grafton ST, Hazeltine E, Ivry RB. Motor sequence learning with the nondominant left hand. A PET functional imaging study. Experimental Brain Research. 2002;146:369–378. doi: 10.1007/s00221-002-1181-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatada Y, Miall R, Rossetti Y. Long lasting aftereffect of a single prism adaptation: directionally biased shift in proprioception and late onset shift of internal egocentric reference frame. Experimental Brain Research. 2006:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00221-006-0437-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hikosaka O, Nakahara H, Rand MK, Sakai K, Lu X, Nakamura K, Miyachi S, Doya K. Parallel neural networks for learning sequential procedures. Trends Neurosci. 1999;22:464–471. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(99)01439-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hikosaka O, Nakamura K, Sakai K, Nakahara H. Central mechanisms of motor skill learning. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2002;12:217–222. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(02)00307-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Japikse K, Negash S, Howard J, Howard D. Intermanual transfer of procedural learning after extended practice of probablistic sequences. Experimental Brain Research. 2003;148:38–49. doi: 10.1007/s00221-002-1264-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J-H, van Donkelaar P. The Human Dorsal Premotor Cortex Generates OnLine Error Corrections during Sensorimotor Adaptation 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3898-05.2006. J Neurosci. 2006;26:3330–3334. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3898-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muellbacher W, Ziemann U, Wissel J, Dang N, Kofler M, Facchini S, Boroojerdi B, Poewe W, Hallett M. Early consolidation in human primary motor cortex. Nature. 2002;415:640–644. doi: 10.1038/nature712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nissen MJ, Bullemer P. Attentional requirements of learning: evidence from performance measures. Cognitive Psychology. 1987;19:1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield R. The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia. 1971;9:97–113. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(71)90067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poldrack RA, Packard MG. Competition among multiple memory systems: converging evidence from animal and human brain studies. Neuropsychologia. 2003;41:245–251. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(02)00157-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Press DZ, Casement MD, Pascual-Leone A, Robertson EM. The time course of off-line motor sequence learning. Cognitive Brain Research. 2005;25:375–378. doi: 10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson EM, Pascual-Leone A, Press DZ. Awareness modifies the skill-learning benefits of sleep. Curr Biol. 2004;14:208–212. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder JP, Wingard JC, Packard MG. Post-training reversible inactivation of hippocampus reveals interference between memory systems. Hippocampus. 2002;12:280–284. doi: 10.1002/hipo.10024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verwey W, Clegg B. Effector dependent sequence learning in the serial RT task. Psychological Research. 2005;69:242–251. doi: 10.1007/s00426-004-0181-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verwey W, Wright D. Effector-independent and effector-dependent learning in the discrete sequence production task. Psychological Research. 2004;68:64–70. doi: 10.1007/s00426-003-0144-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal M, Amorim MA, Berthoz A. Navigating in a virtual three-dimensional maze: how do egocentric and allocentric reference frames interact? Brain Res Cogn Brain Res. 2004;19:244–258. doi: 10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2003.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker MP, Brakefield T, Hobson JA, Stickgold R. Dissociable stages of human memory consolidation and reconsolidation. Nature. 2003;425:616–620. doi: 10.1038/nature01930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willingham D. Implicit motor sequence learning is not purely perceptual. Memory and Cognition. 1999;27:561–572. doi: 10.3758/bf03211549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]