Abstract

Effective therapies for most solid cancers, especially those that have progressed to metastasis, remain elusive because of inherent and acquired resistance of tumor cells to conventional treatments. Additionally, the effective therapeutic window for many protocols can be very narrow, frequently resulting in toxicity. The present study explores an anticancer strategy that effectively eliminates resistant cancer cells without exerting deleterious effects on normal cells. This approach employs melanoma differentiation-induced gene-7/interleukin-24 (mda-7/IL-24), a cancer-specific, apoptosis-inducing cytokine, in combination with nontoxic doses of a chemical compound from the endoperoxide class that decomposes in water generating singlet oxygen. This combinatorial regimen specifically induced in vitro apoptosis in prostate carcinoma cells, with innate resistance to chemotherapy or engineered resistance to mda-7/IL-24, as well as pancreatic carcinoma cells inherently resistant to any treatment modality, including mda-7/IL-24. Apoptosis induction correlated with increased cellular reactive oxygen species production and was prevented by general antioxidants, such as N-acetyl-l-cysteine or Tiron. Induction of apoptosis in combination-treated cancer cells correlated with a reduction in the antiapoptotic protein BCL-xL. In contrast, both normal prostate and pancreatic epithelial cells were unaffected by the single or combination treatment. These provocative findings suggest that this combinatorial strategy might provide a platform for developing effective treatments for therapy-resistant cancers.

Keywords: BCL-xL, cancer-selective apoptosis, endoperoxide, mda-7/IL-24, reactive oxygen species

Subtraction hybridization applied to a human melanoma differentiation model system permitted the cloning of melanoma differentiation-induced gene-7/interleukin-24 (mda-7/IL-24), a member of the IL-10 cytokine family (1). When administered by a replication-incompetent adenovirus (Ad.mda-7), mda-7/IL-24 exhibited nearly ubiquitous antitumor properties in vitro and in vivo, leading to its rapid and successful entry into the clinic, where safety and clinical efficacy of Ad.mda-7 (INGN 241) was confirmed in a Phase I clinical trial in patients with advanced carcinomas and melanomas (2–5). The most intriguing property of mda-7/IL-24 is preferential induction of apoptosis in cancer cells of diverse origin without harming normal cells (2, 4, 5). Additional attributes of mda-7/IL-24 that make it an ideal tool for cancer gene therapy include potent “antitumor bystander” activity, an ability to inhibit tumor angiogenesis, synergy with radiation, chemotherapy and monoclonal antibody therapies, and immune modulatory activity (2–5). These divergent anticancer properties of mda-7/IL-24 imply that it will have a profound impact on the therapy of diverse cancers (2, 4).

Prostate cancer has emerged as the second-leading cause of cancer-related death in the United States, with >200,000 diagnosed cases and >30,000 expected deaths in 2007 (6). With early stage disease, prostatectomy, radiation therapy, and hormone deprivation therapy are effective in many patients, although there is significant morbidity and mortality associated with these procedures (7). Regrettably, most prostate cancer patients ultimately relapse (usually 1–2 years posttherapy), with androgen-insensitive disease and conventional chemotherapeutic agents providing little benefit (7). Consequently, the currently available treatments are not curative, and there is much room for the development of alternative therapies for prostate cancer.

Pancreatic cancer is one of the most aggressive and formidable of the neoplastic diseases, with exceptionally high mortality and no currently effective therapies (8). In these contexts, development of improved treatments for this invariably fatal cancer remains a high priority. Unlike the vast majority of human cancers, ectopic expression of mda-7/IL-24 in pancreatic carcinoma cells remains largely ineffective in promoting cell death (9–11). The mechanism underlying this resistance is related to the expression of oncogenic K-ras, a genetic alteration observed in >90% of pancreatic cancers, which causes a preferential “translational block” of mda-7/IL-24 mRNA (11). Inhibiting K-ras expression allows mda-7/IL-24 protein translation with resultant apoptosis (11). Accordingly, a combinatorial treatment employing mda-7/IL-24 and antisense inhibition of K-ras or inhibition of K-ras-downstream ERK 1/2 signaling induces apoptosis in K-ras mutant pancreatic carcinoma cells and inhibits growth of these tumor cells in murine xenograft models (9). An alternative mechanism for promoting apoptosis by mda-7/IL-24 that is independent of K-ras suppression involves treatment with agents that promote induction of reactive oxygen species (ROS), including N-(4-hydroxyphenyl) retinamide (4–HPR), arsenic trioxide, and dithiophene compound (NSC656240) (10).

ROS such as superoxide radical anion, hydrogen peroxide, singlet oxygen, and the hydroxyl radical and ion are established modifiers of cellular functions affecting development, growth, aging, and survival (12). Overproducing ROS or disturbing the critical balance between ROS and biochemical antioxidants can initiate a lethal chain of reactions that results in damaged cellular integrity and cell death (12–15). This toxicity has been exploited as an effective strategy for treatment of various cancers (14, 16, 17). Several agents have been used to generate ROS, inside or around cancerous tissues, including D-amino acid oxidase, glucose oxidase, xanthine oxidase, arsenic trioxide, hydrogen peroxide, PK11195, 4–HPR, and dithiophene (18, 19).

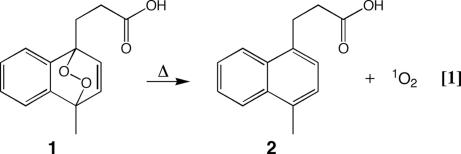

Singlet oxygen is a virtually active ROS whose toxicity has been shown to exceed that of oxygen radicals in inducing apoptosis in certain cells (20, 21). Endoperoxides (EPXs) are a class of compounds that are capable of storing and transporting oxygen, which can be released thermally as singlet oxygen (Fig. 1) (22) [supporting information (SI) Text]. Moreover, the flux of singlet oxygen from the decomposition of EPXs can be tuned over several orders of magnitude to meet the desired biological effect. Singlet oxygen generated in vitro from this manner has been shown to be effective in inactivating enveloped viruses and bacteria, including herpes simplex 1, vesicular stomatitis virus, HIV, and Escherichia coli (23–25).

Fig. 1.

Structure of EPX and scheme of EPX synthesis. EPX (1) has a half-life of 25–30 min at 37°C in PBS (39). The thermal decomposition to yield the propionic acid (2) may follow two paths; roughly 45% follows a concertedly path generating 2 and singlet oxygen, whereas the remainder follows a diradical path generating 2 and ground-state oxygen (40, 41).

Mechanisms by which mda-7/IL-24 promotes cancer-specific apoptosis include ROS induction, mitochondrial destabilization, and modulation of the ratio between pro- and antiapoptotic proteins of the bcl gene family (2, 4, 5). Previous experiments documented that agents capable of altering normal mitochondrial functions and augmenting ROS production potentiate selective killing of prostate cancer cells by mda-7/IL-24 (26). Antioxidants such as N-acetyl-l-cysteine (NAC) and Tiron inhibit Ad.mda-7-induced apoptosis. Similar ROS-dependent effects have been observed in mda-7/IL-24-induced apoptosis in malignant glioma and renal cancer cells (2–5). Furthermore, the importance of ROS in augmenting mda-7/IL-24 killing of pancreatic cancer cells was evident from recent studies demonstrating that a combinatorial treatment with Ad.mda-7 and an ROS-generating agent, including arsenic trioxide, dithiophene, or 4–HPR, promoted cell death in both mutant and WT K-ras pancreatic carcinoma cells by abolishing the mda-7/IL-24 mRNA translational block (10).

In the present study, we expanded on the paradigm and demonstrate that Ad.mda-7, in combination with a new targeted ROS-inducer, EPX, a potent endoperoxide, generating singlet oxygen, specifically kills prostate and pancreatic carcinoma cells. Moreover, this combinatorial treatment selectively induces in vitro apoptosis in prostate cancer cells displaying sensitivity to mda-7/IL-24 or chemotherapy, as well as tumor cells exhibiting intrinsic resistance to chemotherapy or engineered resistance to mda-7/IL-24. Additionally, the combination of Ad.mda-7 + EPX induces programmed cell death in pancreatic carcinoma cells that are inherently resistant to any current treatment modality, including mda-7/IL-24. In contrast, normal prostate and pancreatic cells are unaffected by these agents at doses eliciting deleterious effects in cancer cells. These findings warrant further studies, including those involving in vivo human tumor xenograft and transgenic tumor animal models, to develop and exploit this anticancer therapeutic approach for therapy-resistant tumors.

Results and Discussion

Combination of Ad.mda-7 + EPX Specifically Kills Prostate Cancer Cells but Not Immortalized Normal Prostate Epithelial Cells.

In pilot experiments designed to define the IC50 of EPX for prostate cancer and immortalized normal prostate epithelial cells (P69), EPX efficiently killed both cell types at high concentrations (>2 μM). However, at a dose of <2 μM EPX, cancer-selective toxicity was evident (SI Fig. 7).

Previous studies demonstrated that Ad.mda-7 suppressed growth and induced apoptosis in prostate carcinoma cells DU-145, PC-3, and LNCaP, but not in early passage normal or P69 (normal immortal) cells (26, 27). Based on these findings, we determined whether a combination of Ad.mda-7 and EPX (applied at low, nontoxic doses) would potentiate these selective anticancer properties. Indeed, Ad.mda-7 infection (100 pfu per cell) combined with EPX (1 μM) preferentially killed prostate cancer cells, including two drug-resistant variants DUTR (resistant to taxol) and DURC (resistant to camptothecin), more efficiently than Ad.mda-7 alone (Fig. 2) (26–28). In contrast, no toxicity was observed with Ad.mda-7 or EPX, alone or in combination, in P69 cells (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Combination of low-dose EPX (1 μM) with Ad.mda-7 specifically kills cancer but not P69 cells. The killing effect is abrogated by antioxidant (NAC) pretreatment (5 mM). MTT viability assays were performed on day 5 after treatment with the indicated agent(s). Con, no EPX treatment.

Annexin V staining was used to monitor apoptosis induction by the Ad.mda-7 + EPX combination treatment (Fig. 3). Induction of apoptosis was significantly higher in DU-145, PC-3, LNCaP, DUTR, and DURC cells treated with this combination than in the cells treated with Ad.mda-7 alone (Fig. 3). Overexpression of the antiapoptotic protein BCL-xL renders DU-145 cells resistant to Ad.mda-7 (27, 28). Interestingly, whereas Ad.mda-7 or EPX alone had no effect, the Ad.mda-7 + EPX combination reversed resistance of DU/Bcl-xL cells, resulting in a decrease in survival and an induction of apoptosis (Figs. 2 and 3). Apoptosis was not induced by Ad.mda-7 or EPX, alone or in combination, in P69 cells (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Combination of low-dose EPX with Ad.mda-7 induces apoptosis selectively in prostate cancer cells. Annexin V binding assays were performed 24 h after treatment with the indicated agent(s). Con, no EPX treatment.

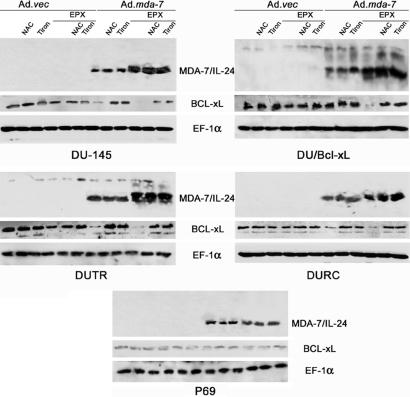

ROS scavengers such as NAC (general antioxidant, 5 mM) and Tiron (superoxide scavenger, 10 μM) abrogated killing in sensitive cells infected with only Ad.mda-7 or in sensitive or resistant cells treated with the Ad.mda-7 + EPX combination (Figs. 2 and 3, data not shown for Tiron). Western blot analysis demonstrated increased expression of MDA-7/IL-24 protein in the DU-145 series of prostate carcinoma cell lines when Ad.mda-7 infection was combined with EPX (Fig. 4). Unexpectedly, pretreatment with NAC or Tiron did not affect the MDA-7/IL-24 protein expression after either Ad.mda-7 single or combination treatment with EPX. The mechanisms by which EPX stimulates MDA-7/IL-24 protein production are currently unknown and are under investigation. This enhancement of the MDA-7/IL-24 protein may occur by a process analogous to that observed with the ROS-inducer treatment of pancreatic cancer cells (9–11), namely by enhancing protein translation through facilitation of the association of mda-7/IL-24 mRNA with polysomes. However, the failure of NAC or Tiron to block this process suggests that EPX may exert this effect by pathways that are antioxidant- and superoxide scavenger-independent. Further studies are necessary to determine whether the ability of EPX to induce a flux of singlet oxygen may override the ability of NAC and Tiron to fully inhibit the downstream events of this treatment, resulting in protein stabilization, but not other cellular changes, which are blocked by antioxidant treatment, such as growth suppression and apoptosis-induction by mda-7/IL-24 alone or in combination with EPX.

Fig. 4.

MDA-7/IL-24, BCL-xL, and EF-1α protein expression in prostate cancer and P69 cells after treatment with EPX, Ad.mda-7, or their combination. Cells were treated as indicated, protein lysates were collected 48 h after treatment, and Western blots were performed as described in Materials and Methods.

EPX Treatment Causes Mitochondrial Dysfunction and ROS Production in Cancer Cells, but Not in Immortalized Normal Prostate Cells.

EPX (half-life = 30 min at 37°C) decomposes in water solution releasing singlet oxygen (Fig. 1). We tested the ability of EPX to induce mitochondrial dysfunction and stimulate cellular ROS production in prostate cancer and P69 cells (Fig. 5). Time course measurements of mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) in P69 and DU-145 cells demonstrated early changes in ΔΨm in DU-145 cells treated with low concentrations of EPX alone (Fig. 5A). The percentage of cells with low ΔΨm increased from 10 to 40% after 1 h of treatment, and this enhanced level of mitochondrial instability was sustained for at least 24 h. Pretreatment with Tiron abolished these changes. In contrast, there was no significant difference in ΔΨm between EPX- and EPX/Tiron-treated P69 cells.

Fig. 5.

EPX treatment promotes mitochondrial dysfunction and elevated ROS (peroxide and/or nitric oxide) production in cancer but not in P69 cells. Cells were treated (with EPX alone or in combination with Ad.mda-7), stained, and analyzed by flow cytometry. (A) Time course of mitochondrial potential changes in P69 and DU-145 cells upon EPX treatment. (B) ROS production in P69 and prostate cancer cells after Ad.vec + EPX or Ad.mda-7 + EPX treatment. Con, no EPX treatment.

Low-dose EPX treatment (1 μM) did not cause detectable intracellular ROS production in either cancer or P69 cells, whereas Ad.mda-7 infection increased production of various (superoxide as well as peroxide and/or nitric oxide) ROS species in prostate cancer cells (Fig. 5B and data not shown). However, the Ad.mda-7 + EPX combination significantly enhanced peroxide and/or nitric oxide species production versus single Ad.mda-7 infection in DU-145 cells, as detected by DCFH-DA staining (Fig. 5B) (26). In contrast, intracellular superoxide production did not change compared with the single Ad.mda-7/IL-24 treatment (data not shown). Both NAC and Tiron pretreatment abrogated the increase in intracellular ROS production (Fig. 5B and data not shown). This increase in intracellular ROS production correlated with augmented apoptosis induction in all of the cell lines tested (Figs. 3 and 5B). In DU/Bcl-xL cells, there was no increase in intracellular ROS production upon treatment with a single agent. However, the combination treatment stimulated significant intracellular peroxide and/or nitric oxide production that correlated with apoptosis induction in these mda-7/IL-24-, chemotherapy-, and radiation-resistant cell lines (Figs. 3 and 5B). It is possible that treatment with EPX increased the levels of mitochondrial instability of cancer cells, rendering them more vulnerable to mda-7/IL-24-induced apoptosis. In P69 cells, the doses of EPX used in this experiment did not affect the mitochondrial status of these cells. Given the absence of mda-7/IL-24-induced effects in normal cells, the combination of both agents did not induce any toxic effects in these cells. Our observation that the single agent or combination has no activity on normal cells is significant, suggesting that this approach might have therapeutic potential for both sensitive (DU-145, PC-3, and LNCaP) and chemotherapy (DUTR and DURC)- and radiation/chemotherapy (DU/Bcl-xL)-resistant prostate cancer cells.

BCL-xL Down-Regulation Is Promoted by the Combination of Ad.mda-7/IL-24 + EPX.

Studies were performed to define potential target genes associated with apoptosis that might be regulated by mda-7/IL-24 + EPX, thereby resulting in selective toxicity in prostate cancer cells. Accordingly, we monitored the levels of expression of the BCL-xL protein in DU-145, DU/Bcl-xL, and P69 cells treated with Ad.mda-7, EPX, or Ad.mda-7 + EPX with and without antioxidant (NAC and Tiron) pretreatment (Fig. 4). BCL-xL protein was down-regulated by Ad.mda-7 alone in sensitive cell lines (DU-145, DUTR, and DURC), but not in a resistant cell line (DU/Bcl-xL) (Fig. 4). However, the combination of Ad.mda-7 + EPX significantly reduced BCL-xL protein in all cells, including DU/Bcl-xL. Antioxidant treatment abolished this reduction and restored the BCL-xL protein level (Fig. 4). EPX or antioxidant (NAC or Tiron) treatment alone did not significantly affect BCL-xL protein levels. Moreover, none of the treatments affected the BCL-xL protein level in P69 cells.

The observation that the combination of EPX + Ad.mda-7 down-regulates BCL-xL is important because in diverse cancers, including prostate cancer, there is a negative correlation between the basal levels of BCL-xL protein expression and sensitivity to standard chemotherapeutic drugs (29). Based on this consideration, it is possible that this combination would override resistance to standard chemotherapy in the clinical setting. We have previously documented that mda-7/IL-24 alters the ratio of proapoptotic (BAX and/or BAK) to antiapoptotic (BCL-2 and/or BCL-xL) proteins selectively in many tumor cells, including melanoma, prostate, malignant glioma, and renal carcinomas, thereby tilting the balance from cancer cell survival to apoptosis (2–5). The mechanism by which Ad.mda-7 alone in sensitive prostate cancer cells or in combination with EPX in DU/Bcl-XL prostate cancer cells reduces BCL-xL protein levels is not currently known. Mechanisms by which Ad.mda-7 and Ad.mda-7 + EPX modulate BCL-XL protein levels could involve changes in phosphorylation and ubiquitination of this protein. The phosphorylation of BCL-2 family proteins is induced by multiple kinases (PKC-α, MAPK, JNK, and others) that in turn are activated by ROS (30). In addition, the expression levels of BCL-2 family proteins are strictly regulated by ubiquitination (31). In a previous study, ROS were shown to suppress phosphorylation of BH4 antiapoptotic proteins in OSC-4 squamous cell carcinoma cells in vitro, which resulted in an increase in the heterodimerization and a decrease in the ubiquitination of proapoptotic proteins (32). Further studies are necessary to determine whether these processes are operational in prostate cancer cells infected with Ad.mda-7 alone or in combination with EPX.

Combination of Ad.mda-7 + EPX Efficiently Kills mda-7/IL-24-Resistant Pancreatic Cancer Cells, but Not Immortalized Normal Pancreatic Mesenchymal Cells in Vitro.

Multiple previous studies have demonstrated that infection of pancreatic cancer cells with Ad.mda-7 does not significantly affect their viability or growth (9–11). A nontoxic concentration of EPX for pancreatic cells was determined (data not shown). This concentration of EPX (0.25 μM), in combination with Ad.mda-7, effectively killed pancreatic carcinoma cell lines independent of their K-ras status and did not exert any harmful effect on immortalized normal pancreatic mesenchymal cells LT2 (Fig. 6A). Ad.mda-7 (100 pfu per cell) or EPX (0.25 μM) alone did not exert any toxic effects on pancreatic carcinoma cell lines. Similar to prostate cancer cells, pretreatment with the superoxide scavenger Tiron protected pancreatic carcinoma cells from Ad.mda-7 + EPX treatment (Fig. 6A). This combination effectively induced apoptosis in pancreatic carcinoma cells (30–40% of cells became apoptotic 48 h posttreatment), which correlated with increased intracellular peroxide and/or nitric oxide production (Fig. 6 B and C, data shown for PANC-1 cells; similar results were obtained with AsPC-1 and BxPC-3). Tiron (10 μM) pretreatment abolished both intracellular ROS production and apoptosis induction by the Ad.mda-7 + EPX treatment.

Fig. 6.

Combination of Ad.mda-7 + EPX (0.25 μM) effectively kills pancreatic cancer cells by apoptosis induction and promotes production of MDA-7/IL-24 protein. Pretreatment with Tiron inhibits killing and blocks MDA-7/IL-24 protein production in combination-treated cells. (A) MTT assays performed at day 5. (B) Annexin V binding assays with PANC-1 cells performed 48 h after treatment. (C) ROS production assays with PANC-1 cells performed 24 h after treatment. (D) Western blot for MDA-7/IL-24 protein in PANC-1 and BxPC-3 cells. Con, no EPX treatment.

Killing and Apoptosis Induction in Pancreatic Cancer Cells Correlate with ROS Production and MDA-7/IL-24 Protein Synthesis.

Mutant K-ras pancreatic carcinoma cells are resistant to Ad.mda-7-induced apoptosis because of a translational block in mda-7/IL-24 mRNA conversion into protein (9, 11). Consequently, targeted inhibition of K-ras expression or its downstream pathways allows mda-7/IL-24 mRNA translation into protein, resulting in apoptosis in mutant, but not in WT, K-ras pancreatic cancer cells (9). Of therapeutic interest, combining Ad.mda-7 with ROS-inducing agents, such as 4–HPR, arsenic trioxide, or dithiophene, rescinded this mda-7/IL-24 mRNA translational block in both WT and mutant K-ras pancreatic cancer cells (10). Based on these considerations and the ability of EPX to induce ROS, we logically tested the capacity of Ad.mda-7 + EPX to abolish the translational block in pancreatic cancer cells. Western blot assays demonstrated that combinatorial-treated pancreatic carcinoma cells expressed MDA-7/IL-24 protein, whereas pretreatment with Tiron prevented MDA-7/IL-24 protein expression (Fig. 6D and data not shown). The presence of mda-7/IL-24 correlated with apoptosis induction and intracellular ROS stimulation in pancreatic carcinoma cells (Fig. 6 and data not shown). Interestingly, the combination of Ad.mda-7 + EPX allowed MDA-7/IL-24 protein translation in pancreatic carcinoma cells independent of their K-ras status (Fig. 6D).

These intriguing studies indicate that a combination of Ad.mda-7 + EPX can affect survival and promote apoptosis in an innately (mda-7/IL-24- and/or chemotherapy-) resistant tumor cell type, namely pancreatic carcinoma in a K-ras-independent manner, without affecting normal pancreatic cells. The ability of Tiron to block apoptosis induction, changes in ΔΨm, and MDA-7/IL-24 production suggests that these effects are related to synergistic induction of ROS by the Ad.mda-7 + EPX combination.

What Is Required to Translate This Combination of Ad.mda-7 + EPX for the Therapy of Resistant Human Tumor Cells?

Although the current studies are very provocative, much research is needed to translate this approach into a viable therapy for patients with resistant cancers. In the context of Ad.mda-7, approaches that more effectively deliver mda-7/IL-24, such as conditionally cancer-specific replicating adenoviruses that promote cancer-selective replication and expression of mda-7/IL-24 (Ad.PEG-E1A.mda-7), hold promise to significantly enhance therapeutic outcomes by using virus gene delivery of this cytokine (2, 33). In the context of human breast cancer, tumors established on both flanks of nude mice when injected on only one side with Ad.PEG-E1A.mda-7 resulted in complete regression of both the primary treated tumor and the distant nontreated tumor. Additionally, multiple studies now indicate that the efficacy of mda-7/IL-24 as an anticancer agent can be significantly augmented by treatment with additional therapeutic agents, such as radiation, chemotherapy, and monoclonal antibodies (2–5) and ROS-inducers, including the present results with EPX. Developing improved adenoviruses and other viral or nonviral vector systems with enhanced cancer tropisms (34) and reduced immunogenicity (35) will also be required to more effectively use the Ad.mda-7 component of this current therapy.

With respect to EPX, approaches for directly delivering this agent to the cancer microenvironment, to avoid damage to normal tissue, is paramount for successfully using this or other compounds of this type clinically. For in vivo targeted delivery, the desired EPX would have to be stable from thermal decomposition or chemical reaction until it reaches the desired target. The payload of delivery of singlet oxygen depends to some extent on the structure of the delivery agent and the environment of the delivery. In the case of EPX, the yield of singlet oxygen is ≈50% in aqueous solution. The wealth of data in the literature regarding EPXs, coupled with supramolecular delivery approaches using nanoparticles, polymers, or liposomes (or other chemical delivery agents), could prove useful for these applications. Alternatively, linking this molecule to an initially inert substrate that results in unique activation in cancer cells would provide a powerful weapon, especially in combination with mda-7/IL-24, against neoplastic diseases. Given cancer cells' increased sensitivity to EPX, this approach remains attractive, and we are working to confirm these possible improved applications.

Summary.

We presently describe a combinatorial approach employing mda-7/IL-24 + EPX for targeting therapeutically resistant cancers for loss of survival and induction of apoptosis. Although further studies are required to precisely define mechanism of action of this combinatorial approach, in principle, this strategy could prove amenable for inducing cell death in other cancer subtypes and might therefore be a general approach for selectively treating both therapy-sensitive and therapy-resistant cancers.

Materials and Methods

Synthesis and Characterization of EPX.

EPX was synthesized from 1-methylnaphalene as described (see SI Text).

Cell Lines, Culture Conditions, and Viability Assays.

DU-145, DU/Bcl-xL, LNCaP, PC-3, P69, PANC-1, AsPC-1, and BxPC-3 cells were cultured as described (11, 26, 27). Taxol- and camptothecin-resistant DU-145 cell lines (DUTR and DURC, respectively) were established as described (36, 37). LT2 cells were obtained from Chemicon International (Temecula, CA) and grown according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cell viability was determined by standard 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assays (26).

Virus Construction, Purification, and Infectivity Assays.

Construction and characterization of Ad.mda-7 and Ad.vec were performed as described (38). Cells were infected with 100 plaque-forming units per cell of Ad.mda-7 or Ad.vec and treated 2 h later with EPX or vehicle control (DMSO). Antioxidant pretreatment was performed simultaneously with Ad infection.

Annexin V Binding Assay, Assessment of Mitochondrial Potential (ΔΨm), and ROS Detection.

Appropriate assays were performed as described in refs. 26 and 27 (see SI Text).

Western Blot Analysis.

Cell extracts in RIPA buffer were prepared, and equal amount of proteins were resolved in SDS/12% PAGE, transferred on PVDF membrane, and evaluated for mda-7/IL-24, BCL-xL, and EF-1α protein levels as described in refs. 26 and 27 (see SI Text).

Statistical Analysis.

Results are expressed as means ± SE of at least three independent experiments. Statistical evaluations were performed by using an unpaired two-tailed Student's t test (P < 0.05 was considered significant).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The present study was supported in part by NIH Grants R01 CA097318, R01 CA098712, and P01 CA104177; the Samuel Waxman Cancer Research Foundation; and the Chernow Endowment. P.B.F. is a Michael and Stella Chernow Urological Cancer Research Scientist and a Samuel Waxman Cancer Research Foundation Investigator.

Abbreviations

- EPX

endoperoxide

- mda-7/IL-24

melanoma differentiation-associated gene-7/interleukin-24

- NAC

N-acetyl-l-cysteine

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- 4–HPR

N-(4-hydroxyphenyl) retinamide.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0700042104/DC1.

References

- 1.Jiang H, Lin JJ, Su ZZ, Goldstein NI, Fisher PB. Oncogene. 1995;11:2477–2486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fisher PB. Cancer Res. 2005;65:10128–10138. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fisher PB, Gopalkrishnan RV, Chada S, Ramesh R, Grimm EA, Rosenfeld MR, Curiel DT, Dent P. Cancer Biol Ther. 2003;2:S23–S37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gupta P, Su ZZ, Lebedeva IV, Sarkar D, Sauane M, Emdad L, Bachelor MA, Grant S, Curiel DT, Dent P, et al. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;111:596–628. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lebedeva IV, Sauane M, Gopalkrishnan RV, Sarkar D, Su ZZ, Gupta P, Nemunaitis J, Cunningham C, Yacoub A, Dent P, et al. Mol Ther. 2005;11:4–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Murray T, Xu J, Thun MJ. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:43–66. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simoneau AR. Rev Urol. 2006;2(Suppl 8):S56–S67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bardeesy N, DePinho RA. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:897–909. doi: 10.1038/nrc949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lebedeva IV, Sarkar D, Su ZZ, Gopalkrishnan RV, Athar M, Randolph A, Valerie K, Dent P, Fisher PB. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2403–2413. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lebedeva IV, Su ZZ, Sarkar D, Gopalkrishnan RV, Waxman S, Yacoub A, Dent P, Fisher PB. Oncogene. 2005;24:585–596. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Su Z, Lebedeva IV, Gopalkrishnan RV, Goldstein NI, Stein CA, Reed JC, Dent P, Fisher PB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:10332–10337. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171315198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thannickal VJ, Fanburg BL. Am J Physiol. 2000;279:L1005–L1028. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.279.6.L1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cejas P, Casado E, Belda-Iniesta C, De Castro J, Espinosa E, Redondo A, Sereno M, Garcia-Cabezas MA, Vara JA, Dominguez-Caceres A, et al. Cancer Causes Control. 2004;15:707–719. doi: 10.1023/B:CACO.0000036189.61607.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mates JM, Sanchez-Jimenez FM. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2000;32:157–170. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(99)00088-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pelicano H, Carney D, Huang P. Drug Resist Updat. 2004;7:97–110. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dolmans DE, Fukumura D, Jain RK. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:380–387. doi: 10.1038/nrc1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hileman EO, Liu J, Albitar M, Keating MJ, Huang P. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2004;53:209–219. doi: 10.1007/s00280-003-0726-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fang J, Sawa T, Akaike T, Akuta T, Sahoo SK, Khaled G, Hamada A, Maeda H. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3567–3574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fennell DA, Corbo M, Pallaska A, Cotter FE. Br J Cancer. 2001;84:1397–1404. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kochevar IE, Lynch MC, Zhuang S, Lambert CR. Photochem Photobiol. 2000;72:548–553. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2000)072<0548:sobnor>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Godar DE. Methods Enzymol. 2000;319:309–330. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)19032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schweitzer C, Schmidt R. Chem Rev. 2003;103:1685–1757. doi: 10.1021/cr010371d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cavalcante AK, Martinez GR, Di Mascio P, Menck CF, Agnez-Lima LF. DNA Repair (Amst) 2002;1:1051–1056. doi: 10.1016/s1568-7864(02)00164-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pellieux C, Dewilde A, Pierlot C, Aubry JM. Methods Enzymol. 2000;319:197–207. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)19020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dewilde A, Pellieux C, Hajjam S, Wattre P, Pierlot C, Hober D, Aubry JM. J Photochem Photobiol B. 1996;36:23–29. doi: 10.1016/S1011-1344(96)07323-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lebedeva IV, Su ZZ, Sarkar D, Kitada S, Dent P, Waxman S, Reed JC, Fisher PB. Cancer Res. 2003;63:8138–8144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lebedeva IV, Sarkar D, Su ZZ, Kitada S, Dent P, Stein CA, Reed JC, Fisher PB. Oncogene. 2003;22:8758–8773. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Su ZZ, Lebedeva IV, Sarkar D, Emdad L, Gupta P, Kitada S, Dent P, Reed JC, Fisher PB. Oncogene. 2006;25:2339–2348. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Amundson SA, Myers TG, Scudiero D, Kitada S, Reed JC, Fornace AJ., Jr Cancer Res. 2000;60:6101–6110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsuzawa A, Ichijo H. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2005;7:472–481. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang Y, Yu X. FASEB J. 2003;17:790–799. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0654rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li D, Ueta E, Kimura T, Yamamoto T, Osaki T. Cancer Sci. 2004;95:644–650. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2004.tb03323.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sarkar D, Su ZZ, Vozhilla N, Park ES, Gupta P, Fisher PB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:14034–14039. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506837102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Noureddini SC, Curiel DT. Mol Pharm. 2005;2:341–347. doi: 10.1021/mp050045c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hedley SJ, Chen J, Mountz JD, Li J, Curiel DT, Korokhov N, Kovesdi I. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2006;55:1412–1419. doi: 10.1007/s00262-006-0158-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Urasaki Y, Laco GS, Pourquier P, Takebayashi Y, Kohlhagen G, Gioffre C, Zhang H, Chatterjee D, Pantazis P, Pommier Y. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1964–1969. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dinnen RD, Drew L, Petrylak DP, Cassai NJS, Broudt-Rauf P, Fine RL. J Biol Chem. 2006 in press. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Su ZZ, Madireddi MT, Lin JJ, Young CS, Kitada S, Reed JC, Goldstein NI, Fisher PB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:14400–14405. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mueller K, Ziereis K. Arch Pharm (Weinheim) 1992;325:219–223. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Turro NJ, Chow MF. J Am Chem Soc. 1981;103:7218–7224. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Turro NJ, Chow MF, Rigaudy J. J Am Chem Soc. 1979;101:1300–1302. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.