Abstract

Gene transcription can be regulated by promoter competition when multiple promoters are available for a single enhancer. The converse, however, is largely undescribed. Here we report an occurrence of several enhancers competing for one promoter (enhancer interference) and propose its underlying mechanism. The promoter targeting sequence from the Abdominal-B locus of the Drosophila bithorax complex overcomes the enhancer-blocking activity of insulators in transgenic embryos. It may facilitate the long-range enhancer–promoter communication in Abdominal-B by bypassing insulator elements such as Frontabdominal-7 and Frontabdominal-8. In transgenic embryos, the anti-insulator activity allowed both an insulator-blocked enhancer and a nonblocked enhancer to contact the same promoter. We found that these two enhancers exhibited mutual inhibition or mutual exclusion in cells where both are transcriptionally active. This enhancer interference occurred at the level of enhancer–promoter communication. It occurred only between enhancers on opposite sides of an insulator and depended on enhancer activity. We hypothesize that enhancer interference limits the interaction of the Abdominal-B promoter to the enhancer(s) from only one regulatory domain in a specific abdominal segment.

Keywords: Abd-B, Fab-8, IAB8, NEE

Specific enhancer–promoter communication is essential for proper gene regulation in complex loci. Promoter competition, an enhancer's preference for a dominant promoter over several other competing promoters, can provide a highly specific method of gene activation (1–3). However, the reverse situation, in which several enhancers compete for a single promoter, is mostly undescribed.

Homeotic selector genes control segmental identities along the anterior–posterior axis during Drosophila development. The Abdominal-B (Abd-B) locus from the bithorax gene complex has an extended downstream regulatory region that is organized into four parasegment (PS)-specific regulatory domains, termed iab-5 (infraabdominal-5), iab-6, iab-7, and iab-8, which control Abd-B transcription in PSs from PS10 to PS13 (Fig. 1A) (4–7). These iab domains are separated by chromatin boundary elements or insulators such as Frontabdominal-7 (Fab-7) or Fab-8 (8–13). Mutations that inactivate a specific iab function usually result in the transformation of an affected segment into a copy of the segment immediately anterior to it. For example, an iab-7 mutation would result in the transformation of PS12 (roughly A7) into a copy of PS11 (A6) (Fig. 1C). One prediction of this phenomenon is that Abd-B selectively interacts with enhancers from a single regulatory domain in a given abdominal segment (13, 14). If this prediction is true, enhancer competition may exist within the Abd-B locus (Fig. 1 B and C).

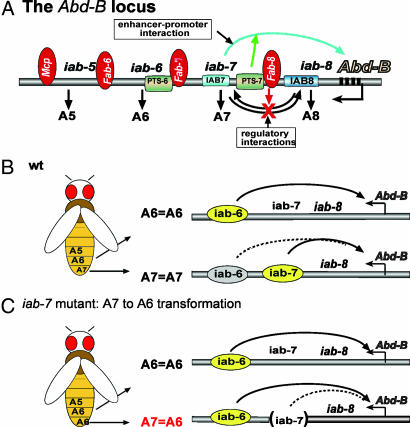

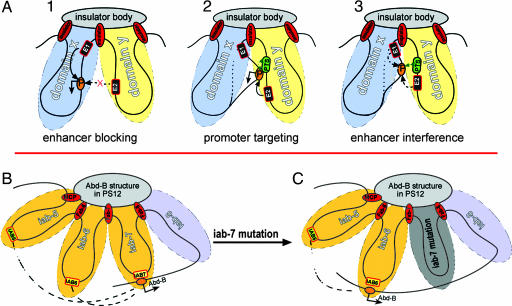

Fig. 1.

Regulatory interactions of the Drosophila Abd-B locus. (A) The Abd-B locus from the Drosophila bithorax complex controls the morphogenesis of the abdominal PS10 to PS14, or roughly the fifth (A5) to the ninth (A9) abdominal segment. Abd-B expression in each PS is regulated by a PS-specific enhancer domain, infra-abdominal (iab). Neighboring domains are separated by insulator or boundary elements such as Fab-7 and Fab-8 to prevent cross-regulations. These insulators do not block enhancer–promoter interactions in Abd-B possibly because of the PTS element(s), which can bypass insulators and target enhancers to Abd-B promoter. (B) Molecular evidence indicates that in progressively posterior abdominal segments more and more enhancer domains are active (ovals). However, genetic evidence suggests that Abd-B is activated dominantly by the corresponding iab domains in a specific segment (yellow ovals). (C) An iab in its corresponding segment is dominant over other iab domains. This is revealed by loss-of-function mutations. For example, when iab-7 is inactivated by deletions (see the gap in iab-7), the neighboring iab-6 could take over the regulatory role of iab-7 in PS12 (A7), resulting in a PS12-to-PS11 transformation (A7 to A6).

The recently identified promoter targeting sequences (PTS) (15–17) overcome the enhancer blocking effect of an insulator and facilitate long-range enhancer–promoter communications in transgenic flies. An important characteristic of the PTS is that it selectively targets a single promoter when there are multiple promoters present in the transgene (17). This selective targeting is strain specific and is epigenetically inheritable through multiple generations (18). The PTS elements may play important roles in enhancer–promoter communication over long distances and intervening boundary elements in the endogenous Abd-B locus (Fig. 1A). In this study we examined how PTS regulates the interactions between a promoter and several enhancers. We report that the PTS renders two enhancers mutually inhibitory in transgenic embryos. This “enhancer interference” depends on enhancer activities and occurs between enhancers located on opposite side of an insulator. This phenomenon supports an enhancer selection model and could be important to limit the Abd-B promoter to the dedicated enhancers in a given abdominal segment.

Results

PTS-7 Mediates Enhancer Interference.

Promoter targeting is typically seen in transgenic embryos when the PTS is inserted near an insulator-blocked enhancer (15, 17, 18). It was previously shown that the suHw insulator (19, 20) blocks the IAB8 enhancer when it is inserted between the enhancer and the 3′ end of lacZ (also see Fig. 2D); however, when PTS-7 is also inserted, IAB8 overcomes enhancer-blocking activity of the insulator and selectively targets one of the transgenic promoters (15). A w-targeted strain is shown in Fig. 2 A and B in which IAB8 only activates w but not lacZ. To test whether PTS mediates enhancer competition, we constructed a transgene to mimic the arrangement of cis elements in the endogenous locus. As shown in Fig. 2, W123 consists of divergently transcribed w and lacZ genes, the suHw insulator, the 625-bp PTS-7, the IAB8 enhancer from the Abd-B locus (Fig. 1A), and the NEE enhancer from the rhomboid gene (21). NEE and IAB8 normally activate additive transgene (w) expressions within overlapping regions in the embryo (Fig. 2C, arrowhead). When PTS-7 and suHw are both inserted between IAB8 and the 3′ end of lacZ, transgenic embryos displayed promoter targeting by IAB8 similar to that of Fig. 2 A and B. In contrast, NEE is not regulated by PTS because it is not blocked by an insulator (18) and it activates both w and lacZ (Fig. 2 E and F).

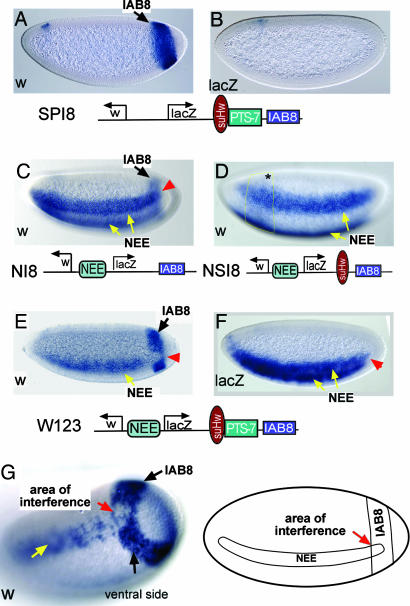

Fig. 2.

Enhancer competition between NEE and the PTS-targeted IAB8. (A) In situ hybridization detection of w expression in embryos from promoter-targeted strains carrying transgenic construct SPI8. All embryos are oriented anterior to the left and dorsal side up. (B) lacZ expression from embryos carrying SPI8. (C) W expression from embryos carrying NI8. The promoter-proximal NEE and the lacZ 3′ located IAB8 are compatible in the overlapping region (see arrowhead). (D) The suHw insulator blocks IAB8 when inserted between the enhancer and the 3′ end of lacZ. (E) When the 625-bp PTS-7 was inserted between suHw and IAB8, PTS could target IAB8 to the w promoter, bypassing the suHw insulator. IAB8 and NEE become mutually excusive in the overlapping region (arrowhead). (F) Staining of lacZ in the same strain showing normal NEE–lacZ interaction. (G) A detailed view of an embryo showing enhancer interference. A schematic drawing to the right shows regions of NEE and IAB8 activity and overlapping region as areas of enhancer interference.

Interestingly, we observed that neither NEE nor IAB8 activates the targeted w promoter in conventional ways (see Fig. 2C): IAB8 selectively directs robust transcription from the w promoter, but, in the region where NEE is also active, IAB8 exhibits almost no transcription activity (arrowhead in Fig. 2E). In contrast, NEE activates w transcription along most of the anterior–posterior axis of the embryo to a similar extent as the controls, but it is inhibited at the most posterior tip, where it overlaps with IAB8 (note the tapering off of the NEE stripe in Fig. 2E). A higher resolution surface image is shown in Fig. 2G. Slight variations exist in the strength of mutual inhibition among different strains. For example, in some strains NEE extends right to the anterior border of IAB8 band (Fig. 2E), whereas in others NEE is inhibited several rows of cells before it enters the Iab8 band (Fig. 2E). We believe this is because of the fact that inhibitory effect is extremely potent and sensitive, which requires only minimal IAB8 enhancer activity so that, in cells slightly outside IAB8 bands, NEE is already affected. We analyzed several lacZ-targeted strains from this construct, and we did not show such an inhibitory effect; however, we detected a similar mutually inhibitory effect on the lacZ promoter from different transgenic constructs (Q.C. and J.Z., unpublished observations, and Fig. 3D), indicating an effect is not unique to the w promoter.

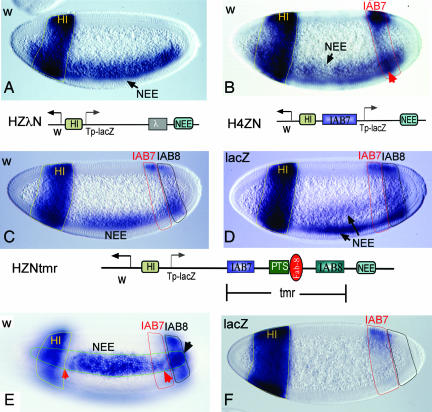

Fig. 3.

Enhancer interference between enhancers from opposite sides of an insulator. (A) Activities of NEE and HI on the w promoter. No interference between the two enhancers in their anterior overlapping region (red arrow) is shown. (B) Transgenic embryos carrying the IAB7 enhancer inserted between HI and lacZ promoter. IAB7 activates transcription in the posterior region of the embryo with left border (arrow) slightly anterior to that of IAB8 (PS12 vs. PS13). In the region where IAB7 and NEE are both active, the two enhancers produce additive transcription activities (red arrow). (C) Stage-5 embryos carrying transgene containing the 9.5-kb tmr. Both NEE and IAB8 from the distal side of Fab-8 are targeted to w. IAB7 activates weak activity detectable only in dorsal region of the embryo (red arrow). (D) A similar result is seen on a lacZ-targeted strain. (E) A surface view from the strain shown in C. Note that gaps (red arrows) appear on NEE as it enters the regions where HI and IAB7 activate transcription. Also note that NEE becomes stronger as it overlaps with IAB8 (black arrow). (F) Staining of lacZ from line shown in C and E. Here only HI and IAB7 are active because they are not blocked by Fab-8.

One possible cause of the mutual exclusion of enhancer activities is a PTS-induced interference between transcription factors such that repressors interacting with one enhancer may silence activators binding to another. However, this is unlikely because NEE activates lacZ normally in the same region of the embryo where activation is prevented from w (arrowhead in Fig. 2F). In addition, the “inhibited” HI enhancer (8, 22) functions normally on lacZ (Fig. 4 D and F). Thus, mutual exclusion does not lead to disrupted enhancer functions. We believe instead that it occurs at a step during enhancer–promoter interaction, probably because of the incompatible modes of activating the w promoter. We call this phenomenon enhancer interference.

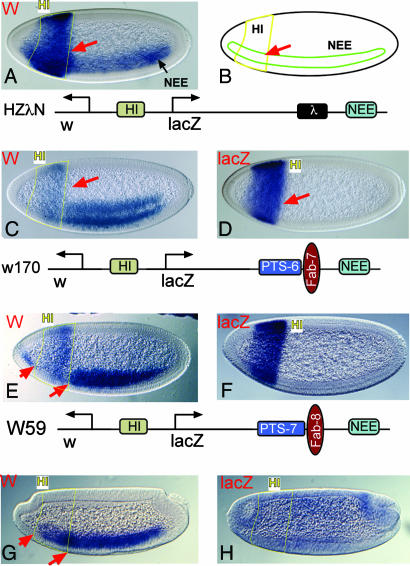

Fig. 4.

Interference between HI and targeted NEE. (A) Activities of NEE and HI on the w promoter. No interference between the two enhancers in their anterior overlapping region (red arrow) is shown. (B) Schematic drawing showing regions of HI and NEE activity. (C) A w promoter-targeted strain carrying W170 showing enhancer interference. Note that NEE appears to be truncated before entering the HI activity region, whereas HI is inhibited (see arrow and compare with A). (D) Expression of lacZ from the same strain as in C. Note that enhancer interference does not affect HI–lacZ interaction. (E) NEE–w targeting is shown by w staining of a transgenic line W59-1. A pronounced gap (between the arrows) exists on NEE–w interaction because of enhancer interference from HI. (F) Activity of lacZ in the same strains as in E showing normal HI activity. (G) Transgenic embryos from strain W59-1 in bcd mutant background. Bcd is required to activate HI. Its loss eliminated HI activity and, consequently, restored NEE function in the head region. (H) Transcription of lacZ in the bcd mutant embryo, showing the loss of HI activity.

Enhancer Interference Depends on Enhancer Activity but Is Independent of the Identities of the Enhancer, the Insulator, and the PTS.

To determine whether enhancer interference is specific to the tested enhancer–insulator combination, we replaced NEE-IAB8 enhancers with the HI (from the hairy gene) (22) and NEE enhancers and replaced suHw with the endogenous Fab-8 insulator. HI and NEE normally produce additive activities in the overlapping regions of the anterior region of the embryo (Fig. 4A). NEE activity is blocked by the insertion of Fab-8 between the 3′ end of lacZ and NEE (15), but when a 1.7-kb DNA fragment containing both the Fab-8 insulator and PTS-7 (11, 15) is inserted (W59 in Fig. 4), NEE becomes targeted. An NEE-w-targeted line is shown in Fig. 4 E and F. Similar to the effect shown in Fig. 2, the proximal HI enhancer is not targeted because it activates both promoters. Importantly, in the anterior part of the embryo where both enhancers are active, the additive activity seen in Fig. 4A no longer exists. Instead, NEE exhibits a gap where HI normally functions (see region between arrows in Fig. 4E). Similarly, HI is also inhibited by NEE (compare Fig. 4 A with E). Unlike the mutual inhibition seen in Fig. 2E, where IAB8 is excluded only in cells in which NEE is also active, the entire HI enhancer is inhibited. This inhibition is likely due to the additional transcriptional activity in the head region (overlapping with HI) that is often associated with NEE (21) (see asterisk in Fig. 2D).

Enhancer interference also occurs when PTS-7 and Fab-8 are replaced by PTS-6 and the Fab-7 insulator (Figs. 1A and 4C) (8, 23). We also tested PTS-7 in the presence of the suHw insulator. We observed a similar, although slightly weaker, interference between HI and NEE (data not shown). Finally, we tested the PTS-7 from Drosophila virilis and found that the D. virilis PTS-7 functions identically to Drosophila melanogaster PTS-7 in terms of promoter targeting and enhancer interference (Q.C., B. Pfeiffer, S. Celniker, and J.Z., unpublished observation). These results suggest that enhancer interference is not specific to a particular enhancer, insulator, or PTS element and represents a conserved incompatibility between enhancers that are differentially regulated by the PTS or an incompatibility between two enhancers originated from different chromatin domains defined by insulators (see below).

The fact that enhancer interference occurs only in cells in which both enhancers are transcriptionally competent suggests that interference depends on enhancer activity. To test this hypothesis, we introduced the w-targeted W59-1 strain (shown in Fig. 4 E and F) into a mutant background for bicoid (bcd), a maternal gap gene required for wild-type HI enhancer activity (22). As predicted, the loss of the Bcd activator obliterated HI activity (compare Fig. 4 F and H), and, consequently, NEE activity was restored in the anterior region of the embryo (Fig. 4G).

Enhancer Interference Occurs only Between Enhancers Separated by an Insulator.

According to the proposal that chromosomes are organized into loop domains by genomic insulators, which may interact with structural components of the nucleus such as the nucleolus or an insulator body (24, 25), a transgenic insulator and endogenous insulators near the transgene insertion site would divide a transgene into two separate loops (Fig. 5A1). As a result, enhancer interference could be interpreted as the incompatibility between enhancers from two domains “forced” to interact with the same promoter by the PTS (Fig. 5A2). In this scenario, the mutual exclusion seen in Figs. 2 and 4 could be interpreted as the w promoter being recruited by enhancers from two incompatible domains but not able to establish productive enhancer–promoter interactions with either one (Fig. 5A3). A further prediction is that enhancer interference occurs only between enhancers located in different domains. Enhancers from the same domain are expected to not exhibit interference.

Fig. 5.

Enhancer interference and enhancer selection models. (A) We propose that enhancer interference is a direct result of forcing a promoter to interact with enhancers from different chromatin domains (A1). The transgenic insulator and nearby genomic insulator divide the transgene into two chromatin domains, X and Y, by interacting nuclear structural components such as insulator body (24). Enhancer1 (E1) interacts with the promoter located in the same domain X, whereas E2 from domain Y does not activate the promoter. (A2) E2 activates the promoter due to the PTS, which may recruit the promoter into domain Y. (A3) In cells where both enhancers are active, the promoter could not be recruited into either domain, resulting in mutual exclusion. It is possible that variations of enhancer strength or timing may lead to either enhancer mutual exclusion or enhancer selection. (B) An enhancer selection model for the Abd-B locus. Insulator elements from Abd-B may interact with a special “Abd-B structure” in the nucleus and organize the locus into multiple segment-specific chromatin loops. In each abdominal segment, Abd-B promoter interacts with one loop. For example, in PS12 (A7), Abd-B communicates exclusively with enhancers such as IAB7 from iab-7. Enhancers from iab-5 and iab-6 are excluded from the Abd-B promoter because of enhancer interference from the dominant IAB7. (C) This interference is removed in iab-7 mutations, which inactivate the enhancer or other regulatory elements necessary for long-range enhancer–promoter interactions. As a result, the IAB6 enhancer now replaces IAB7 to activate Abd-B in PS12, which leads to A7-to-A6 transformation. IAB5 is continually excluded from Abd-B by enhancer interference from IAB6.

To test this hypothesis, we created a construct with two enhancers on each side of an insulator by replacing the 1.7-kb Fab-8/PTS from W59 with the 9.5-kb Transvection mediating region (tmr) from the Abd-B 3′ region (26–28) (HZNtmr in Fig. 3). This region contains the PTS, the Fab-8 insulator, and the IAB7 and IAB8 enhancers (11, 15). In the orientation shown, HI and IAB7 are located on one side of Fab-8 insulator, while IAB8 and NEE on the other. Because NEE activates transcription as anterior-posterior stripes, it overlaps with all of the remaining enhancers in the transgene. In the absence of the insulator and PTS elements, the NEE and HI enhancers displayed additive activities in the overlapping region (Figs. 3A and 4A). Similarly, NEE and IAB7 also produce an additive pattern of transcription activity (see short arrow in Fig. 3B). But when the tmr is present, the additive activities no longer exist. Here both the IAB8 and NEE enhancers selectively activate w but not lacZ over the intervening Fab-8 insulator (Fig. 3 C, E, and F), for PTS-7 from the tmr bypasses Fab-8 and targets both enhancers to the w promoter. Because the IAB7 and HI enhancers are located on promoter proximal side of Fab-8 they are not regulated by PTS-7. As a result, they activate both w and lacZ accordingly (Fig. 3 C, E, and F) (17). In the overlapping regions between the PTS-targeted NEE and these two enhancers, NEE is inhibited: This is evident by the sudden end to the NEE stripe as it extends into the HI territory (left red arrow in Fig. 3E) and the weakening of NEE in the posterior region although IAB7 barely activates w in this embryo (Fig. 3E, red arrowhead). On the other hand, inhibition from NEE is minimal or absent on HI, while it could not be evaluated on IAB7, as the ventral activity of IAB7 is too low to be detectable (see Fig. 3F). In contrast to the mutual inhibition seen between NEE and IAB8 in Fig. 2E, these two enhancers appear additive (Fig. 3E, black arrow), when both are located on the right hand side of the Fab-8 insulator. A similar result is seen between IAB5 and NEE when both were placed on the distal side of the suHw insulator (18). When lacZ-targeted strains were examined, we observed similar enhancer interference as w-targeted lines discussed above (Fig. 3D). These results suggest that enhancer interference occurs only between enhancers located on opposite of an insulator or in different domains defined by insulators.

It should be noted that HI in Fig. 3 C–E does not seem to be inhibited by NEE compared with the embryos in Fig. 4 C and E. This weak inhibition or lack of inhibition holds for the remaining strains that showed NEE-w targeting. It seems that instead of the mutual exclusion seen in Fig. 4E, the w promoter prefers HI over NEE in the overlapping region. Although the exact cause of the difference between the behaviors of enhancers from these two transgenes is unclear, the extra distance between NEE and w (15 kb in HZNtmr vs. 6 kb in W59) may have either delayed or weakened the NEE enhancer. As a result, HI could establish a stable enhancer–promoter interaction with w. These results suggest that when NEE is located far from the promoter it loses the ability to inhibit enhancers located relatively close to the promoter. This is compatible with the notion that in the Abd-B locus, promoter proximal enhancers may exclude distal ones, while distal enhancers have little effect on proximal enhancers.

Discussion

In this study we presented evidence of enhancer interference in transgenic Drosophila embryos. We showed that the PTS allowed two enhancers that are differentially affected by an insulator (i.e., one is blocked by the insulator, while the other is not blocked) to simultaneously activate the same promoter. In the absence of the insulator and the PTS, the two enhancers would normally be compatible and produce additive activities of the promoter in overlapping regions (Figs. 2C and 4A). In the presence of the insulator and the PTS, however, the two enhancers become mutually inhibitory or exclusive in these regions (Figs. 2E and 4 C and E). This enhancer interference depends on enhancer activity but appears to be independent of the identities of enhancers, the insulator, and the PTS elements present in the transgene and thus represents a general property between competing enhancers.

It is not known what mechanism may be responsible for the enhancer interference, but it is conceivable that the PTS may allow direct contact between enhancer and promoter elements located on different chromatin loops organized by insulators. In this model, a transgenic insulator could interact with local genomic insulators to divide the transgene into two chromatin loops (Fig. 5A1), in which case enhancer 2 (E2) could not activate the promoter (P), whereas E1 could. When the PTS is inserted into the transgene, it overcomes the insulator and targets E2 to P (Fig. 5A2) in cells where E2 is active but E1 is not. This promoter targeting could happen by physically recruiting the promoter from domain X into domain Y. However, in cells where both E1 and E2 are active, the promoter is being recruited by opposing forces, and, consequently, no productive transcription takes place (Fig. 5A3).

Enhancer interference activity may be important for enhancer selection in the endogenous locus. In Abd-B, where the regulatory region is organized into multiple domains by insulators, PTS and possibly other types of DNA elements facilitate long-range enhancer–promoter interactions in the locus. But the incompatible nature of enhancers from different domains causes these enhancers to compete for the Abd-B promoter. The strength and distance advantage may render promoter-proximal enhancers dominant over distal ones, leading the Abd-B promoter to interact with the most proximal, transcriptionally active enhancer (e.g., IAB7 in PS12) (Figs. 1B and 5B). Consequently, other enhancers such as IAB5 and IAB6 are excluded from Abd-B in this segment because of enhancer interference. This model explains the loss-of-function mutation in the locus. For example, in an iab-7 mutant, IAB7 is inactivated or unable to make contact with the Abd-B promoter. As a result, IAB6 is no longer excluded and replaces IAB7 in PS12, producing an A7-to-A6 homeotic transformation (Figs. 1C and 5C).

While promoter competition ensures the activation of a specific gene, enhancer competition or enhancer interference could lead to specific ways of controlling one gene by the “selected” enhancers. Considering most complex regulatory regions employ multiple enhancers, enhancer interference could be a necessary mechanism to achieve regulatory specificity.

Materials and Methods

Transgenic Plasmid Construction.

Constructs for Fig. 2.

SPI8 was described by Zhou and Levine (15). NI8 was made by inserting the 300-bp NEE enhancer into the EcoRI-SpeI site of C4PLZ vector, followed by inserting the 1.6-kb BamHI-BglII IAB8 fragment into the BglII site at the 3′ end of lacZ. NSI8 was made by inserting a 360-bp suHw insulator at the BalII site of NI8 vector. W123 was made by inserting the PTS into the BglII site of NSI8.

Constructs for Fig. 3.

H4ZN was built by inserting a 4.0-kb sequence from the tmr containing the IAB7 enhancer into the BamHI site of HZN. HZNtmr was made by inserting the BamHI-BglII fragment into the BglII site of the HZN vector in a reverse orientation (IAB7 in proximal position, whereas IAB8 is in promoter distal position).

Constructs for Fig. 4.

HZλN was made by placing a 228-bp SpeI-BamHI fragment of the HI enhancer (8) between the w and lacZ promoters, adding a blunted 300-bp fragment of the NEE enhancer (8) at the StuI site at the 3′ end of lacZ, and inserting a 1-kb λ spacer sequence at the BglII site between the 3′ end of lacZ and the NEE (8). W170 was made by inserting the 3.7-kb Fab-7 fragment instead of the λ sequence. W59 was constructed by replacing the λ sequence in HZλN with the 1.7-kb DNA from the tmr region containing the 625-bp PTS and the Fab-8 insulator (11).

P-Element Transformation and Genetic Crosses.

P-element transformation vectors containing the mini white gene were introduced into the yw67 fly embryos by microinjection as described previously (29). For each of the transgenic constructs, independent transformants were selected and maintained as transgenic stocks. Bcd mutant allele bcdE1 (22) was obtained from the Bloomington Stock Center (Indiana University, Bloomington, IN) (BL3257). To analyze the transgene W59 in bcd mutant background, staged embryos were collected from the cross with bcdE1 females and w59-1 males and subjected to RNA in situ hybridization.

RNA in Situ Hybridization.

Whole-mount RNA in situ hybridization was performed as described previously (15, 30). Briefly, staged embryos were collected, dechorionated with 50% bleach for 5 min, and fixed with 4% formaldehyde in PBS and heptane for 20 min. Methanol was added to the fixed embryos to remove the vitelline membranes. These embryos were incubated with prehybridization buffer (50% formamide, 4× SSC, 1× Denhardt's solution, 250 μg/ml tRNA, 250 μg/ml ssDNA, 50 μg/ml heparin, 0.1% Tween 20, and 5% dextran sulfate) at 55°C for 1 h and 12–16 h when antisense RNA probes for the specific reporter genes were added to final concentration of 0.25 μg/ml. Embryos were washed with wash buffer (50% formamide, 2× SSC, and 0.1% Tween 20) at 55°C for 4–18 h and PBT for 30 min. Anti-dig-AP antibody (Roche, Pleasanton, CA) was added to the embryo at a 1:2,000 dilution. Color reaction was carried out at room temperature with AP staining buffer containing nitroblue tetrazolium and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate (Roche). Stained embryos were rinsed, fixed with ethanol, and mounted on glass slides.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mike Levine and Francois Karch for fruitful discussions. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM65391 and in part by the March of Dimes Birth Defect Foundation, the Edward Mallinckrodt Jr. Foundation, the Concern Foundation, and the Commonwealth Universal Research Enhancement Program, Pennsylvania Department of Health (J.Z.).

Abbreviations

- PTS

promoter targeting sequence

- PS

parasegment.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS direct submission.

References

- 1.Foley KP, Engel JD. Genes Dev. 1992;6:730–744. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.5.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ohtsuki S, Levine M, Cai HN. Genes Dev. 1998;12:547–556. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.4.547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saleh A, Davies GE, Pascal V, Wright PW, Hodge DL, Cho EH, Lockett SJ, Abshari M, Anderson SK. Immunity. 2004;21:55–66. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karch F, Weiffenbach B, Peifer M, Bender W, Duncan I, Celniker S, Crosby M, Lewis EB. Cell. 1985;43:81–96. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casanova J, Sanchez-Herrero E, Morata G. Cell. 1986;47:627–636. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90627-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Celniker SE, Sharma S, Keelan DJ, Lewis EB. EMBO J. 1990;9:4277–4286. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07876.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanchez-Herrero E. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1991;111:437–449. doi: 10.1242/dev.111.2.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou J, Barolo S, Szymanski P, Levine M. Genes Dev. 1996;10:3195–3201. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.24.3195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hagstrom K, Muller M, Schedl P. Genes Dev. 1996;10:3202–3215. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.24.3202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mihaly J, Hogga I, Gausz J, Gyurkovics H, Karch F. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1997;124:1809–1820. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.9.1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou J, Ashe H, Burks C, Levine M. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1999;126:3057–3065. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.14.3057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barges S, Mihaly J, Galloni M, Hagstrom K, Muller M, Shanower G, Schedl P, Gyurkovics H, Karch F. Development (Cambridge, UK) 2000;127:779–790. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.4.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mihaly J, Hogga I, Barges S, Galloni M, Mishra RK, Hagstrom K, Muller M, Schedl P, Sipos L, Gausz J, et al. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1998;54:60–70. doi: 10.1007/s000180050125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vazquez J, Farkas G, Gaszner M, Udvardy A, Muller M, Hagstrom K, Gyurkovics H, Sipos L, Gausz J, Galloni M. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1993;58:45–54. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1993.058.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou J, Levine M. Cell. 1999;99:567–575. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81546-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muller J. Curr Biol. 2000;10:R241–R244. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00374-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin Q, Wu D, Zhou J. Development (Cambridge, UK) 2003;130:519–526. doi: 10.1242/dev.00227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin Q, Chen Q, Lin L, Zhou J. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2639–2651. doi: 10.1101/gad.1230004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geyer PK, Corces VG. Genes Dev. 1992;6:1865–1873. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.10.1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dorsett D. Genetics. 1993;134:1135–1144. doi: 10.1093/genetics/134.4.1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ip YT, Park RE, Kosman D, Bier E, Levine M. Genes Dev. 1992;6:1728–1739. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.9.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Riddihough G, Ish-Horowicz D. Genes Dev. 1991;5:840–854. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.5.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen Q, Lin L, Smith S, Lin Q, Zhou J. Dev Biol. 2005;286:629–636. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Capelson M, Corces VG. Biol Cell. 2004;96:617–629. doi: 10.1016/j.biolcel.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yusufzai TM, Tagami H, Nakatani Y, Felsenfeld G. Mol Cell. 2004;13:291–298. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00029-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hendrickson JE, Sakonju S. Genetics. 1995;139:835–848. doi: 10.1093/genetics/139.2.835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hopmann R, Duncan D, Duncan I. Genetics. 1995;139:815–833. doi: 10.1093/genetics/139.2.815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sipos L, Mihaly J, Karch F, Schedl P, Gausz J, Gyurkovics H. Genetics. 1998;149:1031–1050. doi: 10.1093/genetics/149.2.1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rubin GM, Spradling AC. Science. 1982;218:348–353. doi: 10.1126/science.6289436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tautz D, Pfeifle C. Chromosoma. 1989;98:81–85. doi: 10.1007/BF00291041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]