Abstract

In a ‘diary’ study, we examined the frequency and affective implications of 34 ethnic minority students' comparisons to other ethnic minorities or to members of a high-status ethnic majority (i.e., European-Americans). Participants made more frequent comparisons to ethnic majority than ethnic minority referents, although neither type of comparison tended to be perceived in terms of group membership (see also Smith & Leach, 2004). Comparisons to ethnic majority referents did not alter participants' positive affect even where they suggested poor future prospects in status-relevant domains. In contrast, comparisons to fellow ethnic minorities led to increased positive affect when they suggested a future prospect of improvement. We discuss the conceptual and practical implications of social comparison in the context of group status.

Much of what people think, feel, and do is a result of how they see themselves in comparison to others (for a review, see Suls & Wheeler, 2000). Thus, individuals who tend to make unflattering comparisons with other individuals evaluate themselves poorly, feel badly, and have little interest in improvement (e.g., Leach et al., 2005). Although people may tend to experience their comparisons to other individuals as inter-personal in nature (Smith & Leach, 2004), group membership can play an important role. For example, it has been argued that members of low-status groups can suffer an ‘unsatisfactory,’ ‘negative’ (see Ellemers, 1993; Tajfel & Turner, 1979), or ‘stigmatized’ (see Crocker & Major, 1989) identity if they face frequent unflattering comparisons with referents whose group is high-status in the domain of comparison (e.g., academic competence, economic status, social status).

Given the presumption that unflattering comparisons with referents of high-status groups are extremely unpleasant, it has been suggested that members of low-status groups engage in at least two (‘self-protective’ or ‘socially creative’) strategies to make such comparisons infrequent (for reviews, see Crocker & Major, 1989; Ellemers, 1993; Pettigrew, 1967; Tajfel & Turner, 1979). First, members of low-status groups reduce the frequency of their comparisons with referents from high-status groups by physically and psychologically avoiding them. Both the social identity and stigma approaches suggest that members of low-status groups should tend to avoid comparisons to referents of high group status in those domains most relevant to the out-group's high-status (see Crocker & Major, 1989; Tajfel & Turner, 1979). For example, they suggest that women should tend to avoid comparing their salaries to men's salaries because this out-group's higher status will remind women of their lower economic status. Second, the stigma and social identity perspectives suggest that members of low-status groups increase the frequency of their comparisons with referents from their own, or other, low-status groups through physical and psychological approach. Presumably, by approaching comparisons with referents of similar status, members of low-status groups reduce the risk that their comparisons will be unflattering.

Despite its conceptual and practical importance, there has been little research on the actual frequency with which members of low-status groups compare themselves to referents from low and high-status groups. Thus, we know little about whether they avoid referents from high-status groups and approach referents from low-status groups. By extension, little is known about the psychological implications of the frequency with which such comparisons are made. Thus, this paper extends H.J. Smith and Leach (2004) to address these issues. Armed with a subtle measure of referents' group membership, we examine the role of the referents' group status in the affective implications of social comparison. In an integration of work at the individual and group levels, we assess the degree to which participant's perceived future prospect of improvement helps explain the affective implications of their comparisons to referents from low and high-status groups.

GROUP STATUS AND SOCIAL COMPARISON

Ostensible support for the view that members of low-status groups experience their comparisons to referents from high-status groups as unpleasant comes from experiments that expose individuals to potential referents who are successful in status-relevant domains. These studies show that exposure to a successful referent from a high-status group is experienced as less pleasant than exposure to a referent from a low-status group (e.g., Blanton, Crocker, & Miller, 2000; Martinot, Redersdorff, Guimond, and Dif, 2002, study 1 and 2; Mussweiler, Gabriel, & Bodenhausen, 2000, study 3). For example, Martinot et al. (2002, study 2) made salient women's low-status in a ‘male domain’ and then exposed them to a (male or female) referent successful in this domain. These women showed less positive self-evaluation when faced with a successful male referent. However, like most studies of this type, the absence of a ‘no comparison’ control condition or baseline measures of self-evaluation makes it unclear if the comparison to the referent with high group status was unpleasant in an absolute sense.

If exposure to referents from high-status groups is less pleasant, then exposure to referents from low-status groups is necessarily more pleasant for members of low-status groups. Indeed, members of real world (e.g., Blanton et al., 2000) and experimentally created (e.g., Brewer & Weber, 1994; Mussweiler et al., 2000, study 2) low-status groups show higher positive affect and self-evaluation when exposed to a successful referent from a low-status group than when exposed to a referent from a high-status group. Both the stigma and social identity approaches tend to interpret this as a ‘socially creative’ strategy aimed at self-protection against comparisons to referents of high group status (e.g., Blanton et al., 2000; Mussweiler et al., 2000). This implies that low group status determines the psychological implications of individuals' comparisons to referents who share their low-status (see Crocker & Major, 1989; Schmitt & Branscombe, 2002; Tajfel & Turner, 1979).

In our view, previous theory and research suggest at least three issues deserving of further attention. First, previous studies have tended to expose individuals to potential referents and to presume that particular comparisons led to specific effects. Whether participants actually compare themselves, or interpret the comparison in the way presumed, is rarely assessed. Thus, we directly assess the comparisons that members of low-status groups make during the course of their everyday lives. We also assess the degree to which they interpret these comparisons as suggesting something about their own future prospects (see below).

Second, single experiments cannot establish the natural frequency of comparisons to referents from high- and low-status groups. Thus, they are in a poor position to examine whether members of low-status groups avoid referents from high-status groups and approach referents from low-status groups in an effort at self-protection. For this reason, we adopt a longitudinal ‘diary’ method to assess social comparisons several times a day, over the course of seven days. To assess the group status of the referent to whom the participant compared, we used a subtle measure that did not require either party's group membership to be salient (for a different approach, see Smith & Leach, 2004).

Third, previous studies have shown only that members of low-status groups experience exposure to potential referents from high-status groups as less pleasant than exposure to potential referents from low-status groups. Thus, the prevailing view that unflattering status-relevant comparisons to referents from high-status groups are especially unpleasant has not been examined adequately. For this reason, we more precisely assess the affective implications of comparison by measuring the positive affect felt before and after it. Although informed by the prevailing stigma and social identity views, our approach is grounded in the alternative perspective on the role of group membership in social comparison offered by reference group theory.

REFERENCE GROUP THEORY

Although most contemporary work assumes that it is an inter-group status relation that makes in-group membership important to social comparison (for reviews, see Crocker & Major, 1989; Schmitt & Branscombe, 2002; Tajfel & Turner, 1979), reference group theory (see Hyman, 1942; Merton, 1957) argues that in-group membership operates more autonomously. It argues that important group memberships provide an implicit ‘frame of reference’ that makes fellow group members highly relevant referents for comparison (for a review see Leach, 2005). Thus, reference group theory argues that in-group membership affects social comparison even where the in-group, and its status relative to other groups, is not especially salient (e.g., Miller, Turnbull, & McFarland, 1988; for reviews see Leach, 2005; Major, 1994). As such, reference group theory suggests that members of low-status groups should be more affected by comparisons with referents from their own, or other, low-status groups than by comparisons with referents from high-status groups (see Hyman, 1942; Major, 1994). Similar views were expressed by Sartre (1948/1976) and Fanon (1967) in their analyses of the psychological effects of low group status. For example, Sartre (1948/1976, pp. 136–138) argued that well adjusted, ‘authentic’ Jews use their own group as a standard by which to evaluate themselves:

The authentic Jew abandons the myth of the universal man[…]. He knows that he is one who stands apart, untouchable, scorned, proscribed—and it is as such that he asserts his being[…]. He chooses his brothers and his peers; they are other Jews[…]. In this isolation to which he has consented, he becomes again a [… person], a whole [… person].

In emphasizing the greater relevance of in-group referents, reference group theory provides a distinct alternative to the stigma and social identity approaches to the social comparisons of individuals with low group status. In contrast to the prevailing view that members of low-status groups avoid comparison with referents from high-status groups in status-relevant domains because they are likely to be unflattering and thus unpleasant, reference group theory suggests that comparison to referents from high-status groups should have little relevance and thus little effect on members of low-status groups. Thus, even where such comparisons are frequent and unflattering, reference group theory suggests that they should not be unpleasant.

Reference group theory also contrasts with the prevailing view that members of low-status groups approach comparisons with referents of similar status as a self-protective strategy. Given its presumption that it is comparisons to similarly situated referents that are most relevant, reference group theory cannot presume that such comparisons are necessarily pleasant (Hyman, 1942; Miller et al., 1988). Thus, it suggests that members of low-status groups experience comparisons to similarly situated referents as pleasant only where these comparisons are interpreted in a way that is flattering. Unflattering comparisons to similarly situated referents should be experienced as unpleasant (Hyman, 1942). Thus, rather than presuming that comparisons to similarly situated referents are necessarily pleasant for members of low-status groups, a reference group theory approach must aim to understand what makes such comparisons flattering or unflattering.

Future Prospect of Improvement

Theory at the inter-personal level suggests that it is an individual's interpretation of the future prospects suggested by a social comparison that makes it flattering or unflattering. Wills (1991) argued that where a relevant comparison suggests good future prospects (e.g., that future improvement is likely) it is flattering and thus experienced as pleasant. Where a comparison suggests poor future prospects (e.g., that future improvement is unlikely) it is unflattering and thus experienced as unpleasant.1 Consistent with this, a great deal of research shows that social comparisons that suggest a future prospect of improvement tend to be pleasant, psychologically. For example, individuals who interpret comparisons with successful referents (e.g., Burleson, Leach, & Harrington, 2005; Lockwood & Kunda, 1999) or unsuccessful referents (e.g., Gibbons & Boney McCoy, 1991; Gibbons, Gerard, Lando, & McGovern, 1991) as suggesting their own future prospect of improvement evaluate themselves positively and/or feel positively. In contrast, comparisons that suggest against a future prospect of improvement tend to be unpleasant, psychologically. For example, individuals who interpret comparisons with successful referents (e.g., Burleson et al., 2005; Lockwood & Kunda, 1999) or unsuccessful referents (Buunk, Collins, Taylor, VanYperen, & Dakof, 1990) as suggesting against their own future prospect of improvement evaluate themselves less positively and/or feel less positively. Thus, it is the future prospect of improvement that a comparison suggests, rather than whether the referent is successful or unsuccessful, that determines its psychological implications (Buunk et al., 1990; Hyman, 1942; for a review, see Leach, 2005).

Because reference group theory suggests that it is the comparisons with referents of similar status that are most relevant, members of low-status groups should be most affected by the future prospect of improvement suggested by their comparisons with referents of low group status. This suggests that members of low-status groups should experience comparisons to referents from low-status groups as pleasant when they suggest a future prospect of improvement. Such comparisons should be unpleasant when they suggest against a future prospect of improvement. In its identification of the conditions under which comparison to referents of similar status are pleasant and unpleasant for members of low-status groups, reference group theory offers a distinctive alternative to the prevailing stigma and social identity perspectives, which tend to view such comparison as necessarily self-protective.

Because reference-group theory suggests that referents from high-status groups are less relevant for members of low-status groups, they should be less affected by the future prospect of improvement suggested by these comparisons. This means that even where comparisons with referents from high-status groups suggest a future prospect of improvement in a status relevant domain, these comparisons should not be especially pleasant. And, even where comparisons with referents from high-status groups suggest against a future prospect of improvement in a status relevant domain, they should not be especially unpleasant. Therefore, reference group theory offers predictions different from the prevailing stigma and social identity perspectives, which expect members of low-status groups to be most affected by their comparisons to referents of high group status in status-relevant domains.2

METHOD

Participants

Through public advertisements, word of mouth, and visits to ethnic organizations and ethnic studies classes at a mid-sized university in the western United States, we offered payment to ethnic minority students willing to participate (see also Smith & Leach, 2004). Of the 34 participants recruited, one person reported identifying as European-American and another failed to report the ethnicity of any of her referents, leaving 32 (9 men, 23 women) participants. Fifteen participants identified as Latino/a, 5 as African-American, and 12 as Asian-American/Pacific Islander. Their age ranged from 18 to 33, with a mean of 23. Participants' average yearly income was $20,000.

Participants came from ethnic groups that were a distinct minority at the university. For this particular academic year, only 21% of the student population identified themselves as belonging to an ethnic minority group. As is the case more generally in the United States, ethnic minority students at this university had less economic resources than their European-American peers and tended to be the first in their family to attend university (Velasquez-Andrade, Hurtado, Ostroff, Rodriguez & Cronin, 2003). Indeed, Velasquez et al. (2003) showed that ethnic minority students from this university felt isolated, under-represented, and disadvantaged compared to their European-American peers.

Procedure

We modeled our procedure and materials after Wheeler and Miyake's (1992) social comparison diaries (for full details see Smith & Leach, 2004). However, in contrast to their focus on inter-personal comparison, in a preliminary orientation meeting we defined social comparison as comparing oneself or one's group to another person, group, idea or experience. At this meeting, participants completed a questionnaire that included measures of identification with their ethnic group (which preliminary analyses showed to be unimportant here).3 For the next 7 days, participants completed a diary entry describing their most recent social comparison (if one occurred) each time they were paged. We paged participants three times each day, during morning, afternoon, and evening blocks of time.4

Participants were provided with a booklet that contained 21 one-page diaries. As in Wheeler and Miyake (1992), participants were asked the sex of their referent, their relationship to the referent, and the medium of their comparison (for general results see Smith & Leach, 2004, Study 2).

Measures

Domain

To assess the domain of comparison, we provided participants with 18 different ‘topics.’ Some of these domains were relevant to the status of the ethnic groups at the university (e.g., ‘academic skill,’ ‘wealth,’ ‘social status’), whereas others were not (e.g., ‘personality,’ ‘life experience,’ ‘family situation,’ ‘relationship’). We also provided an opportunity for participants to write in the domain of their comparison if it did not fit the available categories.

Referent's Group Status

Based on Wheeler and Miyake's (1992) question regarding referent gender, we asked participants to report the ethnicity of the person with whom they compared (unless the comparison was to an entire group). By comparing the ethnicity of the referent to the self-reported ethnicity of the participant, we generated an indicator of whether these ethnic minorities compared themselves to an ethnic minority referent or to a referent from the (high-status) ethnic majority. Unlike a direct question about whether group membership was salient at the time of comparison, this measure did not require participants to attend to their ethnic group membership. It is therefore a more subtle and indirect assessment of the role of group membership than that used in Smith and Leach (2004).

Positive Affect

As in Wheeler and Miyake (1992), participants were asked how they felt just before their comparison with bi-polar emotion pairs. We added the adjective pairs; insecure–confident, anxious–calm, and bad–good to the original pairs of discouraged–encouraged and depressed–happy. Each emotion pair was presented with a −3to +3 seven-point scale to reinforce the valence of each emotion anchor. We use participant's positive affect before the comparison as a control measure. To assess subsequent positive affect, participants rated the same set of adjectives in reference to their feelings just after their social comparison.

Future Prospect of Improvement

We adapted Wheeler and Miyake's (1992) question regarding similarity to the referent to assess participant's perceived future prospect of improvement (see Wills, 1991). Thus, we asked the degree to which participants saw themselves as ‘likely to improve’ in the future with a seven-point Likert-type response scale anchored by 1 (very unlikely) and 7 (very likely).

RESULTS

Prevalence

From their 21 opportunities, participants reported between 1 and 16 social comparisons (M = 8.60, SD = 4.39). As is common in this kind of sample, 74% of participants' comparisons were made to a referent of the same gender (for a review see Major, 1994). This asymmetry, in conjunction with the fact that most participants were women, prevented us from examining the role of gender group membership.

Referent's Group Status

The overwhelming majority of these ethnic minorities' comparisons to out-group referents were made to the European-American majority (87%) rather than to members of other ethnic minority groups. In the analyses reported below, we contrasted comparisons made to referents from this (high-status) ethnic majority with comparisons made to referents from participants' own, or another, ethnic minority group. Models in which comparisons to participant's ethnic in-group were contrasted with comparisons to ethnic out-groups produced similar results.

One hundred thirty-eight (36%) of participants' comparisons were made to ethnic minority referents and one hundred seventy-three (45%) were made to ethnic majority referents. Ethnicity was not recorded in the remaining 19% of comparisons, mainly because these comparisons were made to large-scale categories that were ethnically heterogeneous (e.g., students, fellow employees; see Smith & Leach, 2004). Participants were no more likely to experience their comparisons as group-based when they involved an ethnic minority rather than an ethnic majority referent, χ2 (1) < 0.001, p = 0.99. Thus, participants reported thinking of themselves as a member of a specific group in 23% (31) of their comparisons to an ethnic minority referent and 23% (39) of their comparisons to an ethnic majority referent. Even though participants reported the group membership of the referent, they rarely described their comparisons as explicitly based on their own or their referent's group membership. This pattern supports our decision to assess the group membership of referents subtly and indirectly.

Features of Comparison

Participants' frequency of comparison to ethnic minority and ethnic majority referents did not appear dependent on the specific features of the comparison.

Domain

Across the 18 major domains of comparison, participants were more likely to compare to ethnic minority referents only in the domains of ‘relationship’ (61%), ‘social skills’ (61%), or ‘opinion’ (58%). However, these status-irrelevant domains were less frequently the topic of comparison (i.e., 18% of the total). In contrast, participants' comparisons in status-relevant domains comprised 50% of the total and tended to be made to ethnic majority referents. Thus, of the 20% of comparisons made in the domain of academic competence (i.e., ‘intelligence,’ ‘academic skill,’ and ‘talent’), 51% were made to ethnic majority referents. Of the 17% of comparisons made regarding economic status (i.e., ‘wealth,’ ‘possessions’), 60% were made to ethnic majority referents. Of the 13% of comparisons made in the domain of social status (i.e., ‘social status,’ ‘popularity,’ ‘lifestyle’), 59% were made to ethnic majority referents. Thus, in contrast to the prevailing conceptual view, these ethnic minorities did not appear to avoid comparisons to referents from high-status groups in the domains relevant to their status.

Medium and Relationship to Referent

Participants tended to make comparisons to ethnic majority referents across all possible mediums. Thus, at least 64% of the comparisons made in person, during conversation, in observation, or through the media were to an ethnic majority referent. In addition, participants tended to make comparisons to ethnic majority referents no matter what their relationship to them was. Thus, at least 60% of comparisons to strangers, models, authorities, clients, acquaintances, peers, and close friends were to an ethnic majority referent. Participants' comparisons to romantic partners (50%) and family members (89%) were more likely to be made to ethnic minority referents. However, these two categories comprised only 13% of total comparisons.

Future prospect of improvement

Before examining the affective implications of participants' comparisons, we examined whether they saw their comparisons to ethnic minority referents as suggesting different future prospects than their comparisons to ethnic majority referents. Given that each participant's diary entries reflect within-person variation over time, we utilized Hierarchical Linear Modeling to analyze this data (HLM; Bryk & Raudenbush, 1992). Positive affect before comparison was treated as a control variable (by centering it at its grand mean and treating it as a fixed parameter).

Pre-comparison positive affect did not predict participants' perceived future prospect of improvement, b = 0.094, SE = 0.085, p = 0.280. Also, group status of the referent was not a reliable predictor, b = 0.276, SE = 0.173, p = 0.120. However, the direction of this effect was that comparisons to ethnic minority referents suggested a greater future prospect of improvement than comparisons to ethnic majority referents.

To be sure that participants' comparisons in domains relevant to their low-group status (i.e., academic competence, social and economic status) did not operate differently than other comparisons, we added this variable to the model examined above. Participants were no less likely to perceive a future prospect of improvement when comparisons were made in status-relevant domains, b = −0.133, SE = 0.188, p = 0.48. In addition, the domain of comparison did not moderate the effect of the group status of the referent, b = 0.622, SE = 0.504, p = 0.23. Thus, participants were no less likely to think they would improve when they compared themselves to a referent from a high-status group in the domains relevant to group status.

Increased positive affect after comparison

To address our main interest, we estimated an HLM model predicting positive affect after comparison. As this model treated pre-comparison positive affect as an independent predictor of positive affect after comparison, the outcome variable assessed the increase in positive affect from pre- to post-comparison. The predictors in the model included, perceived future prospect of improvement, referent's group status, and their interaction.

As should be expected, pre-comparison positive affect was a strong and highly reliable predictor of post-comparison positive affect, b = 0.448, SE = 0.106, p < 0.001. However, the referent's group status did not predict increased positive affect, b = 0.038, SE = 0.121, p = 0.755. That is, comparisons to ethnic minority referents were no more or less pleasant than comparisons to ethnic majority referents.

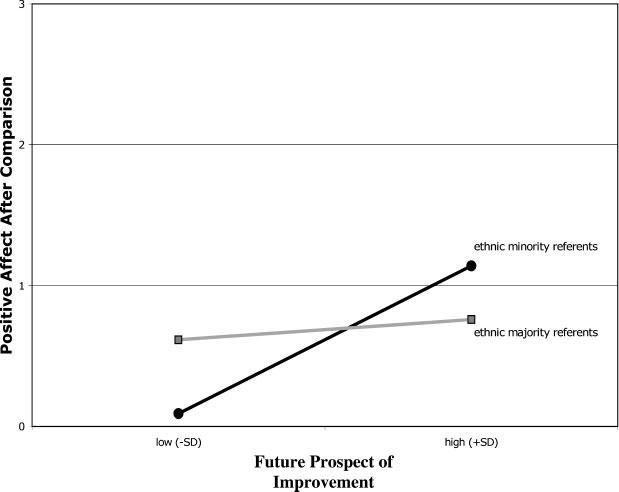

As we expected, participants' perceived future prospect of improvement was an important determinant of how they experienced their social comparisons. Comparisons that suggested a future prospect of improvement led to increased positive affect, b = 0.154, SE = 0.056, p = 0.010. However, the group status of the referent moderated this effect, b = 0.207, SE = 0.105, p = 0.057. Participants' perceived future prospect of improvement was a stronger predictor of increased positive affect after comparisons with referents from low-status groups. The ‘simple slopes’of future prospect of improvement are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Increased positive affect after comparison with ethnic minority or ethnic majority referents (when future prospect of improvement is high or low)

These ethnic minorities' comparisons to referents from the ethnic majority tended to lead to a slight increase in positive affect. However, the future prospect of improvement these comparisons suggested, did not contribute to this positive affect, b = 0.042, SE = 0.084, p = 0.621. No matter how much participants thought their comparisons to ethnic majority referents suggested their own future improvement, it did not increase the positive affect they reported after this comparison. This contrasts with the role of future prospect of improvement in participants' comparisons to ethnic minority referents, b = 0.304, SE = 0.059, p < 0.001. Where participants' comparisons to fellow ethnic minorities suggested against a future prospect of improvement, they did not increase positive affect. However, where comparisons with fellow ethnic minorities suggested a future prospect of improvement, comparisons led to greatly increased positive affect.

Moderation by domain of comparison?

To assess whether the domain of comparison moderated the above results, we added this variable to the model examined above. Whether comparisons were made in status-relevant domains had no independent effect on positive affect, b = 0.025, SE = 0.128, p = 0.85. In addition, the domain of comparison did not moderate the effects of the other variables (all p > 0.45). In fact, including the domain of comparison in the analysis served only to make the effects reported above stronger. Thus, independent of positive affect before comparison (b = 0.497, SE = 0.107, p < 0.001), the perceived future prospect of improvement led to increased positive affect after comparison, b = 0.176, SE = 0.041, p < 0.001. And, the future prospect of improvement was a stronger predictor of increased positive affect after comparisons with referents from low-status, rather than high-status, groups, b = 0.301, SE = 0.086, p = 0.002. Thus, regardless of the domain, comparisons to referents of similar low-status were extremely pleasant for these ethnic minorities when they suggested a future prospect of improvement. And, even where comparisons to referents of high-group status suggested against a future prospect of improvement in a status-relevant domain, participants did not experience them as unpleasant.

DISCUSSION

These ethnic minority participants made more comparisons to ethnic majority than ethnic minority referents. This likely reflects the fact that they are in the numerical minority and thus have more opportunities to compare to members of the high-status ethnic majority. As we recruited participants from ethnic organizations, and they tended to identify highly with and feel very proud of their ethnicity (see footnote 3), it is unlikely that they made more comparisons to the ethnic majority referents as a result of weak attachment to their ethnic group. Thus, in contrast to what is suggested by the prevailing stigma and social identity views, these ethnic minorities did not appear to avoid comparisons to referents from high-status groups or to approach comparisons to referents from low-status groups. Importantly, there was no evidence of these presumably self-protective strategies when participants compared themselves in the domains relevant to their low group status (i.e., social and economic status, academic competence).

Participants experienced as much positive affect after comparisons to referents from other ethnic minorities as they did after comparisons to referents from the ethnic majority. In fact, comparisons to ethnic majority referents were not unpleasant even where they were made in the domains relevant to the ethnic majority's high-status. Neither were such comparisons unpleasant when they suggested against the future prospect of improvement. Thus, despite their prevalence, comparisons to referents of high-group status appeared to be largely irrelevant to these ethnic minority participants. Although this contrasts with what is suggested by the prevailing stigma and social identity views, it is highly consistent with the hypotheses we derived from reference group theory.

Also in contrast to the prevailing view, these ethnic minorities' comparisons to referents from low-status groups were not necessarily pleasant (and thus self-protective). Rather, the affective implications of these comparisons were determined by the future prospect of improvement they suggested. Where comparison suggested future improvement they felt better, where it suggested against future improvement they felt worse. Thus, consistent with reference group theory, similarly situated others served as the most relevant reference for individuals' interpretation of their future prospects.

We explored naturalistic social comparisons over time, rather than participants' interpretations of a single artificially constructed comparison opportunity. Our approach did not demand that participants directly experience their comparisons in terms of their group membership (cf. H.J. Smith & Leach, 2004). Yet whether their comparisons were to ethnic minority or ethnic majority referents played a systematic role in determining whether participants' perceived future prospect of improvement led to increased positive affect. Although the overwhelming majority of participants' social comparisons were subjectively experienced as inter-personal in nature, the group status of their referents altered the implications of their perceived future prospect of improvement. This is consistent with the idea that group status provides an implicit frame of reference for social comparisons. Thus, neither in-group membership nor inter-group status need be salient for social comparisons to be affected by them.

Methodological concerns

We should acknowledge that our approach had possible limitations. The first, and most obvious, limitation is that we had no control over the comparisons participants chose to report. Therefore it is possible that a great deal of (perhaps motivated) subjectivity entered into participants' judgments of their referents. This may have influenced participants' affect after comparison. However, it is important to note that while the imposition of known referents offers some methodological control, it does not eliminate participants' subjective judgment of the referent or their own future prospects. A second possible limitation to our approach is that the intensive nature of data collection limited the number of participants. However, this was balanced by the statistical power generated by repeated measurement of participants' comparisons. Third, like most studies of this type, our sample was not random or representative. Thus, it is important not to assume that our results generalize to all ethnic minorities or members of other low-status groups.

Implications

There is little doubt that members of low-status groups sometimes have to face unflattering comparisons to referents from high-status groups. Indeed, the ethnic minorities in this study often compared their academic competence, economic status, and social status to that of their European-American peers, who are collectively more successful in these domains (Velasquez-Andrade et al., 2003). Social identity and stigma approaches suggest that a prevalence of such comparisons should hurt members of low-status groups. Thus, members of low-status groups are expected to use socially creative strategies (see Ellemers, 1993; Tajfel & Turner, 1979) or to avoid such comparisons for the sake of self-protection (see Crocker & Major, 1989; Schmitt & Branscombe, 2002). We think our results question the prevailing stigma and social identity views in at least two ways.

First, in contrast to the prevailing view, there were no circumstances under which these ethnic minorities experienced comparisons to ethnic majority referents as unpleasant. These ethnic minorities did not perceive their future prospect of improvement as especially poor after comparisons with ethnic majority referents. Neither did they experience decreased positive affect after comparisons with referents of high group status. Indeed, participants did not experience as unpleasant comparisons with referents of high group status even when they suggested against future improvement in a status relevant domain. Given that the stigma and social identity views make the exact opposite prediction, they have difficulty accounting for the present results.

As reference group theory suggests that members of low-status groups tend to see comparisons to referents of high group status as less relevant, the present results are consistent with this currently less popular approach. Our results are also consistent with psychological theorists (Fanon, 1967) and cultural critics (Sartre, 1948/1976) who have questioned the assumption that members of low-status groups necessarily compare themselves to the standard represented by those high in status. Whether status is legitimate or illegitimate, stable or unstable, there may be little reason to presume that referents of high group status offer a relevant standard of comparison to members of low-status groups (see Hyman, 1942; Merton, 1957; see also footnote 2). The very fact that referents of high group status are differentially situated makes them a less relevant reference than those who share an individuals' low group status (see Major, 1994).

Second, these ethnic minority's comparisons to ethnic minority referents were not especially frequent and were not necessarily pleasant. Thus, the present results are inconsistent with the prevailing view that members of low-status groups make frequent comparisons with referents of low group status as a socially creative or self-protective strategy to avoid comparisons with referents from high-status groups (see Crocker & Major, 1989; Pettigrew, 1967; Tajfel & Turner, 1979). Despite their relative infrequency, comparisons to referents of similar status appeared to be most relevant to these ethnic minorities. That it was the future prospect of improvement suggested by a similarly situated referent that most affected participants' positive affect is broadly consistent with reference group theory.

Rather than being a defensive, self-protective attempt to emphasize their solidarity with (e.g., Marinot et al., 2002), or to bask in the reflected glory of (e.g., Blanton et al., 2000; Mussweiler et al., 2000), a referent of low-group status, participants appeared to be pleasantly ‘inspired’ when their most relevant comparisons suggested a prospect of future improvement (see Leach et al., 2005). As referents who share one's social situation serve as the best reference for gauging one's future improvement (e.g., Burleson et al., 2005; Leach et al., 2005), referents of low group status are the most relevant reference for members of low-status groups. That they experience relevant comparisons that suggest their future improvement as pleasant seems quite normal, rather than socially creative or self-protective. As such, group membership appears to affect social comparison through determining by whose standard individuals interpret their future prospects.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

As both authors contributed equally the order of names was determined by a coin toss. Portions of this research were presented at the 2000 Western Psychological Association annual meeting. Smith and Leach (2004) used a portion of the data for a different purpose. This research was supported by NIMH grant # 1 R15 MH62096 01A1 and by faculty research funds from the academic senate at the University of California, Santa Cruz. We thank Elisa Velasquez, Tracey Cronin, and Dani Citti for their assistance. We also thank Eileen Zurbriggen, Larissa Z. Tiedens, Russell Spears, Thomas Schubert, Thomas Kessler, Tracey Cronin, Ngaire Donaghue, as well as the handling editor and reviewers for their helpful comments and advice.

Footnotes

Contract/grant sponsors: NIMH; Contract/grant number: 1 R15 MH62096 01A1; Sonoma State University.

Those familiar with the concept of status stability in the social identity tradition (see Tajfel & Turner, 1979), may see some parallels between it and the concept of future prospect of improvement. However, we believe that the two concepts are distinct. Whereas (in)stability is typically used to characterize the possibility that the structure of inter-group status can change, the future prospect of improvement is an individual's perception of their personal likelihood of improvement. Thus, future prospect of improvement focuses on (1) individual change rather than a change in social structure, (2) improvement in particular, rather than change in general, and (3) a specific perception that improvement is likely for the individual, rather than the more general possibility that inter-group status can change. In addition, the two concepts address different levels of analysis. Whereas the future prospect of improvement focuses on individual improvement within the context of a low-status reference group, status instability focuses on group improvement within the context of an inter-group relation. Again, this difference in emphasis reflects differential concern for intra-group and inter-group comparison respectively.

As researchers in the social identity tradition view the legitimacy of social status as central to the operation of social comparison (see Schmitt & Branscombe, 2002; Tajfel & Turner, 1979), some may have preferred to see it included conceptually and empirically. However, we think that the exclusion of legitimacy has little relevance for our particular interests. Indeed, neither the stigma nor social identity approaches argue that the legitimacy of inter-group status itself determines the pleasantness of comparisons to referents of high group status (see Crocker & Major, 1989; Schmitt & Branscombe, 2002; Tajfel & Turner, 1979). For example, members of low-status groups are expected to feel unpleasant after comparison to a successful referent of high group status whether they are legitimately or illegitimately successful (see Crocker & Major, 1989; Schmitt & Branscombe, 2002). Although the unpleasant experience of the referent's legitimate success may be self-focused and self-critical and the unpleasant experience of the referent's illegitimate success may be other-focused and other-critical (Leach et al., 2005), whatever its legitimacy the comparison is expected to be unpleasant affectively. Thus, legitimacy seems an unlikely moderator of our examination of positive affect after social comparison.

In Smith and Leach (2004, Study 2) we found ethnic identification to be associated with the frequency with which participants explicitly mentioned their own or their referents' group membership in their comparison. However, neither ethnic identification nor pride predicted the frequency of comparison to ethnic minority or ethnic majority referents here (both p > 0.10). In addition, neither ethnic identification nor pride predicted perceived likelihood of improvement or perceived likelihood of getting worse (both p > 0.10). Importantly, this absence of effects cannot be explained by a lack of ethnic identification or measurement error. For example, the 7-point Likert-type scale of ethnic pride proved internally consistent (α = 0.84) and garnered very strong agreement (M = 6.31, SD = 0.95).

30.6% of the social comparisons were reported between 9 am and 1 pm, 34.5% were reported between 1 and 5 pm, and 31.9% were reported between 5 and 9 pm. This pattern did not appear to vary by the participants' or the referents' gender or ethnicity. However, participants did report slightly fewer comparisons to out-group referents during the morning (27%) than the afternoon (37%) or evening (36%) time blocks. This pattern may have occurred because participants were more likely to be at home in the morning and at work or school later in the day.

REFERENCES

- Blanton H, Crocker J, Miller DT. The effects of in-group and out-group social comparison on self-esteem in the context of a negative stereotype. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2000;36:519–530. [Google Scholar]

- Burleson KP, Leach CW, Harrington D. Upward social comparison and self-concept: inspiration and inferiority among art students in an advanced program. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2005;44:109–123. doi: 10.1348/014466604X23509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer MB, Weber JG. Self-evaluation effects of interpersonal versus intergroup social comparison. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;66:268–275. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.66.2.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryk AS, Raudenbush SW. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Buunk BP, Collins RL, Taylor SE, VanYperen NW, Dakof GA. The affective consequences of social comparison: Either direction has its ups and downs. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;59:1238–1249. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.59.6.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Major B. Social stigma and self-esteem: The self-protective properties of stigma. Psychological Review. 1989;96(4):608–630. [Google Scholar]

- Ellemers N. The influence of socio-structural variables on identity management strategies. In: Stroebe W, Hewstone M, editors. European review of social psychology. Vol. 4. Wiley; Chichester: 1993. pp. 27–57. [Google Scholar]

- Fanon F. Black skin, white masks. Grove Wiedenfeld; New York, NY: 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Boney McCoy S. Self-esteem, similarity, and reactions to active versus passive downward comparison. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;60:414–424. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Gerard M, Lando HA, McGovern PG. Social comparison and smoking cessation: The role of the ‘typical ’ smoker. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1991;27:239–258. [Google Scholar]

- Hyman HH. The psychology of status. Archives of Psychology. 1942;269 [Google Scholar]

- Leach CW. Toward a unified theory of social comparison. University of Sussex; 2005. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Leach CW, Smith RH, Webster JM, Iyer A, Kelso K, Garonzik R. The phenomenology of upward comparison: Contrast-based Inferiority and assimilation-based inspiration. 2005 Manuscript under review. [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood P, Kunda Z. Increasing the salience of one's best selves can undermine inspiration by outstanding role models. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1999;76(2):214–228. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.76.2.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major B. From social inequality to personal entitlement: the role of social comparisons, legitimacy appraisals, and group membership. In: Zanna MP, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. Vol. 26. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 1994. pp. 293–355. [Google Scholar]

- Martinot D, Redersdorff S, Guimond S, Dif S. In-group versus outgroup comparisons and self-esteem: The role of group status and identification. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2002;28:1586–1600. [Google Scholar]

- Merton RK. Social theory and social structure. 2nd edn Free Press; Glencoe: 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Miller DT, Turnbull W, McFarland C. Particularistic and universalistic evaluation in the social comparison process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;55:908–917. [Google Scholar]

- Mussweiller T, Gabriel S, Bodenhausen GV. Shifting social identities as a strategy for deflecting threatening social comparisons. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:398–409. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.3.398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew TF. Social-evaluation theory: Convergences and applications. In: Levine D, editor. Nebraska symposium on motivation. Vol. 15. University of Nebraska Press; Lincoln, NB: 1967. pp. 241–311. [Google Scholar]

- Sartre JP. Anti-semite & jew. Schocken; New York, NY: 1976. (Originally Published 1948) [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt MT, Branscombe N. The meaning and consequences of perceived discrimination in disadvantaged and privileged groups. In: Stroebe W, Hewstone M, editors. European review of social psychology. Vol. 12. Wiley; Chichester, England: 2002. pp. 167–199. [Google Scholar]

- Smith HJ, Leach CW. Group membership and everyday social comparison experiences. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2004;34:297–308. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suls J, Wheeler L, editors. Handbook of social comparison theory and research. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; New York, NY: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H, Turner JC. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In: Austin WG, Worshel S, editors. The social psychology of intergroup relations. Brooks/Cole; Monterey, CA: 1979. pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Velasquz-Andrade E, Hurtado S, Ostroff WL, Rodriguez RA, Cronin TJ. First generation, low–income undergraduate students at sonoma state: Factors and characteristics supporting their academic success. Sonoma State University; 2003. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler L, Miyake K. Social comparison and everyday life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;62(5):760–773. [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA. Similarity and self-esteem in downward comparison. In: Suls J, Wills TA, editors. Social comparison: Contemporary theory and research. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1991. pp. 51–78. [Google Scholar]