Abstract

Site-specific fluorescent labeling of proteins in vivo remains one of the most powerful techniques for imaging complex processes in live cells. Although fluorescent proteins in many colors are useful tools for tracking expression and localization of fusion proteins in cells, these relatively large tags (>220 aa) can perturb protein folding, trafficking and function. Much smaller genetically encodable domains (<15 aa) offer complementary advantages. We introduce a small fluorescent chelator whose membrane-impermeant complex with nontoxic Zn2+ ions binds tightly but reversibly to hexahistidine (His6) motifs on surface-exposed proteins. This live-cell label helps to resolve a current controversy concerning externalization of the stromal interaction molecule STIM1 upon depletion of Ca2+ from the endoplasmic reticulum. Whereas N-terminal fluorescent protein fusions interfere with surface exposure of STIM1, short His6 tags are accessible to the dye or antibodies, demonstrating externalization.

Keywords: fluorescent protein, HisZiFiT, live cell labeling, zinc

Nondestructive optical imaging of protein localization, fate and function in live cells is presently most commonly achieved by expressing the protein as a fusion to a fluorescent protein (FP) (1). The exquisite selectivity of genetic targeting allows high sensitivity of detection with no background except cellular autofluorescence. However, FPs are full-sized proteins of at least 220 aa, so they can severely perturb folding, trafficking, and function of proteins to which they are fused. FPs require up to several hours to mature and develop fluorescence, which is too slow for some applications. Genetically encoded tags for most spectroscopic readouts other than fluorescence are unknown. Therefore, several groups have devised hybrid genetic/organic alternatives in which a short (<20 aa), genetically encoded peptide motif binds a small-molecule spectroscopic reporter with sufficient specificity and affinity to be useful in or on living cells (2). Two of the best-known examples are the tetracysteine/biarsenical (1, 3) and the hexahistidine/Ni2+-nitrilotriacetate (His6-Ni2+-NTA) systems (4–8), which have their own limitations. Tetracysteines function only when fully reduced and are therefore most applicable to the cytosolic and nuclear compartments. Smelly 1,2-dithiol antidotes are required to minimize arsenical toxicity. Ni2+ is also a toxic heavy metal and a listed human carcinogen (9–11). Its paramagnetism tends to quench any nearby fluorophores.

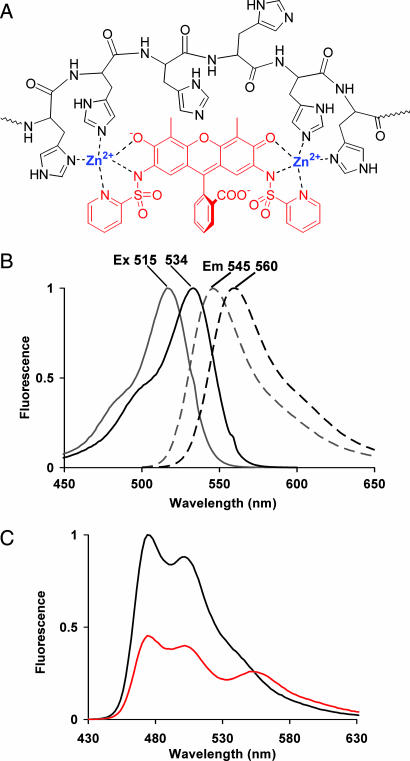

Within the genetically encoded amino acids, histidine has the greatest ability to bind a variety of transition metals in an oxidizing environment. We have replaced the bridging Ni2+ ions by Zn2+, which is ubiquitous in biological systems, nutritionally and physiologically essential, diamagnetic, and redox-inert. Because Zn2+ is not a fluorescence quencher, we designed the fluorophore to participate directly in metal chelation, resulting in a more compact structure as well as excitation and emission wavelength shifts upon Zn2+ binding. The Zn2+-chelating molecule, 2′,7′-bis(pyridyl-2-sulfonamido)-4′,5′-dimethylfluorescein (histidine-zinc fluorescent in vivo tag, HisZiFiT), consists of a fluorescein derivatized with a pair of 2-pyridylsulfonamido functionalities to bind two Zn2+ ions while leaving enough vacancy in the metal coordination shells for further binding to multiple imidazole side chains of the His6 motif (Fig. 1A). Placement of the two pyridylsulfonamides at the 2′,7′-positions insures that they bind separate Zn2+ ions, whereas 4′,5′-substituents can jointly coordinate a single Zn2+ ion (12), saturating its coordination capacity and leaving no detectable affinity for oligo-histidine binding. After describing the synthesis, spectra, and binding properties of HisZiFiT and its complexes, we show that it is a useful label for surface-exposed hexahistidine-tagged proteins. In particular, it resolves a current controversy in Ca2+ signaling mechanisms.

Fig. 1.

Structure and spectra of HisZiFiT. (A) Structure of HisZiFiT (red) and proposed mode of Zn2+-mediated binding to a His6 sequence (black), in flattened projection. (B) Normalized fluorescence excitation (solid curves) and emission (dashed) spectra of 1 μM HisZiFiT without Zn2+ (gray curves) and with saturating (10 μM) free Zn2+ (black). (C) FRET response of His6-CFP to HisZiFiT binding (ex420). Emission spectrum of 1 μM His6-CFP with 10 μM buffered free Zn2+ before (black curve) and after (red curve) addition of 1 μM HisZiFiT.

Recently, STIM1 (stromal interaction molecule 1) has been recognized as a key mediator by which depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores, particularly the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), triggers compensatory Ca2+ influx across the plasma membrane (PM) (13–18). When the ER is replete with Ca2+, STIM1 is largely resident in the ER membrane as an integral membrane protein with its N terminus in the lumen of the ER and its C terminus in the cytosol. Depletion of ER Ca2+ is sensed by a Ca2+-binding domain (“EF hand”) on STIM1, somehow triggering translocation of STIM1 to the PM, where it plays a crucial role in activating channels for Ca2+ entry. The controversy is whether STIM1 docks to the cytosolic face of the PM without surface exposure (15, 19, 20), or instead becomes inserted into the PM (13, 17, 21, 22), presumably via some sort of exocytosis in which the formerly luminal N terminus becomes extracellular (17). A fusion of yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) to the N terminus of the STIM1 (YFP-STIM1) translocated rapidly from the ER to punctate aggregates near the PM, but antibodies against the FP did not detect surface-exposed YFP, leading to the conclusion that STIM1 does not incorporate into the PM (15, 19). An analogous GFP-STIM1 fusion was not quenched by extracellular acidification, again showing that the pH-sensitive GFP was not surface-exposed (20). A triple-HA tag (41 aa including linkers) or horseradish peroxidase (>300 aa) fused to the N terminus of STIM1 likewise remained intracellular (20). By contrast, external exposure of STIM1 was reported to increase after Ca2+ store depletion, based on immunoelectron microscopy of permeabilized cells and Western blotting for STIM1 after neutravidin collection of surface biotinylated complexes (13). Also, pretreatment of intact cells with antibodies against the N terminus of STIM1 reduced subsequent Ca2+ entry (17). However, the surface biotinylation results (see also refs. 21 and 22) have been criticized as possibly reflecting either dead cells or complexes between buried STIM1 and another surface-exposed protein (19, 20). The immunoelectron microscopy (13) was criticized as having insufficient spatial resolution to distinguish surface exposure from close apposition to the cytosolic face of the plasma membrane (20). Because HisZiFiT rapidly, directly, and nondestructively labels very short surface-exposed His6 motifs, it is well suited to resolve this controversy.

Results

The synthesis of HisZiFiT [supporting information (SI) Fig. 5] began with nitration of 4′,5′-dimethylfluorescein, where the methyl substituents confined nitration to the 2′,7′ positions. Reduction of the nitro groups yielded 4′,5′-dimethyl-2′,7′-diaminofluorescein, which was reacted with 2 equivalents of 2-pyridylsulfonyl chloride (23) to give the desired fluorescent chelator. Formation of the Zn-dye complex shifts fluorescence excitation/emission maxima from 515/545 nm to 534/560 nm (Fig. 1B) and slightly increases the quantum yield from 0.3 to 0.4. These spectral shifts were nearly complete at 1 μM free Zn2+, so buffers with 1 or 10 μM free Zn2+ were used for binding to hexahistidine motifs. Although such binding caused no further spectral shifts, it could be monitored by fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) from His6-CFP to HisZiFIT (Fig. 1C). Addition of 1 μM HisZiFiT to stoichiometric amounts of His6-CFP protein in saturating 10 μM Zn2+ buffer quenched the CFP by ≈50%. In the absence of either Zn2+ or His6-fusion, binding to the FP was not observed (SI Fig. 6). The proposed binding mode of the HisZiFiT-Zn2+ complex to the oligohistidine peptide is schematized in Fig. 1A. The binding affinity of the HisZiFiT-Zn2+ complex to a His6 peptide was determined by surface plasmon resonance (Biacore, Piscataway, NJ). Approximately 0.2 pmol of the N-terminally biotinylated peptide was coupled to streptavidin-coated sensor chips. Refractive index changes due to HisZiFiT binding were fitted to a KD of HisZiFiT-Zn2+ to His6 of ≈40 nM (SI Fig. 7), comparable to KD values for His6 binding to bis-Ni2+-NTA ligands (68 nM), but much lower than mono-Ni2+-NTA ligands (1–20 μM KD values) (6, 7).

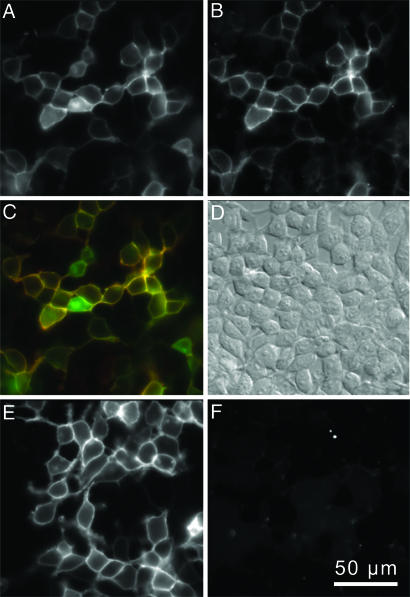

The first biological tests of HisZiFiT were on live HEK293T cells expressing His6-tagged CFP anchored via glycosylphosphatidylinositols (GPIs) to the surface of the PM membrane (His6-CFP-GPI) (24) although some His6-CFP-GPI also remains in intracellular organelles (Fig. 2A). HisZiFiT (100–200 nM) was administered with free Zn2+ buffered to 1 μM with histidine. Surface staining by the impermeant HisZiFiT-Zn2+ complex was complete in <1 min. After two washes with dye-free HBSS, transfected cells clearly exhibited membrane specific fluorescent staining (Fig. 2B). When images in Fig. 2 A and B were overlaid with the CFP channel in green and the HisZiFiT channel in red (Fig. 2C), the PM contained both signals and appeared yellow, whereas His6-CFP-GPI that had not yet reached the cell surface remained green. Control cells expressing the CFP-GPI protein without a His6-tag (Fig. 2E) showed no specific staining (Fig. 2F). HisZiFiT attached to His6-CFP-GPI could be rapidly removed by washing with a strong Zn2+ chelator such as EDTA (SI Fig. 8).

Fig. 2.

HisZiFiT labeling is specific for cell-surface His6-tagged proteins. (A–D) HEK293T cells expressing His6-CFP-GPI, labeled with 100 nM HisZiFiT in 1 μM buffered free Zn2+. (A) CFP channel, ex420/em475, shows both surface and internal His6-CFP-GPI. (B) HisZiFiT channel, ex540/em595, of the same cells shows only plasma membrane outlines. (C) Merge of A (displayed in green) and B (red). (D) Differential interference contrast image of the same cells. (E and F) Control HEK293T cells expressing nontagged CFP (CFP-GPI), identically exposed to HisZiFiT. (E) CFP channel. (F) HisZiFit channel shows negligible staining of CFP–GPI protein.

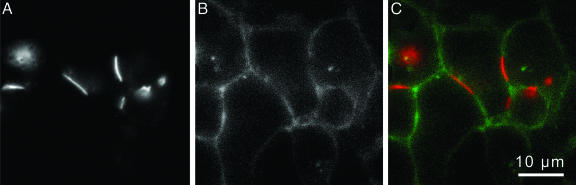

To demonstrate that His6/HisZiFIT-Zn2+ and the tetracysteine/biarsenical systems do not interfere with each other chemically or spectrally, we coexpressed His6-CFP-GPI and connexin43 C-terminally tagged with a tetracysteine motif (Cx43–4C) (25) in HEK293T cells. ReAsH staining of the gap junctions formed by Cx43-4C for 30 min (Fig. 3A), followed by 1 min of HisZiFiT staining of the surface His6-CFP (Fig. 3B), permitted site-specific labeling of two different proteins in the same PM (merge of images Fig. 3 A and B in Fig. 3C). Interestingly, the His6-CFP-GPI appears partially excluded from the gap junctions, which consist of a paracrystalline array of connexins occupying most of the surface area within the plaque (26).

Fig. 3.

Orthogonal staining of HEK293T cells expressing two proteins on the PM. (A) Connexin43–4C with an intracellular tetracysteine motif, stained with ReAsH (ex568/55, em653/95). (B) His6 on extracellular PM surface stained and visualized with HisZiFiT (ex495/10, em535/45). (C) Merge of images A and B representing HisZiFiT staining of His6-CFP-GPI (green) and ReAsH staining of Connexin43–4C (red).

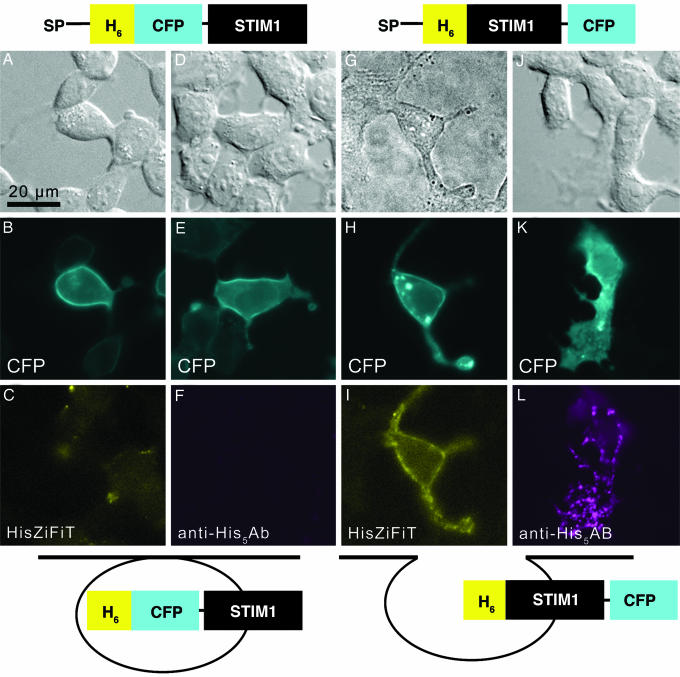

We then applied HisZiFiT to a currently controversial question in cell biology, the surface exposure of the stromal interaction protein STIM1 after depletion of Ca2+ stores. Because endogenous STIM1 is reported to become incorporated into the PM and therefore surface exposed (13, 17, 21, 22) whereas YFP, GFP, an HA tag, or horseradish peroxidase fused to the N terminus of STIM1 remain unexposed (15, 19, 20), we wondered whether bulky tags could prevent membrane insertion of the STIM1 fusion. We therefore created two His6-tagged STIM1 fusion proteins, SP(signal peptide)-His6-CFP-STIM1 and SP-His6-STIM1-CFP (Fig. 4; complete sequences in SI Fig. 9), differing only in the placement of the CFP initially within the lumen of the ER or in the cytosol respectively. Imaging the CFP channel 24–48 h after transient transfection of the genes into HEK293T cells revealed that both fusions showed the expected ER expression before stimulation (data not shown) as well as translocation to the PM after thapsigargin-induced depletion of stored Ca2+ (Fig. 4 B, E, H, and K). Cells expressing the His6-STIM1-CFP protein (Fig. 4I), but not those expressing His6-CFP-STIM1 (Fig. 4C), showed HisZiFiT labeling of cell-surface N-terminal His6 tags. This difference between the two constructs was confirmed by staining of live unpermeabilized cells with a monoclonal antibody against His5 and visualization with a secondary Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated antibody (Fig. 4 F and L). Again, surface exposure was detectable when His6 was the only N-terminal tag (Fig. 4L), but not when CFP was additionally inserted at the N terminus of STIM1 (Fig. 4F). However, HisZiFiT labeling appeared laterally more uniform, whereas antibodies gave a more punctate or beaded staining pattern. This difference may arise because HisZiFiT binds a single His6 motif, whereas primary antibodies are bivalent and are further cross-linkable by secondary antibodies, thus promoting lateral aggregation or capping. Antibody staining of His6-STIM1 without the CFP at the C terminus gave images (SI Fig. 10) similar to Fig. 4L, showing that STIM1 location is not perturbed by a C-terminal fluorescent protein fusion.

Fig. 4.

N-terminal tagging with His6 but not CFP allows cell surface exposure of STIM1. (A–L) Images of cells transiently transfected with His6-CFP-STIM1 (A–F) or His6-STIM1-CFP protein (G–L). Cartoons above A–L schematize the expressed polypeptide domains, where SP denotes signal peptide and H6 stands for His6. (A, D, G, and J) Transmitted light images; images in A, D, and J show differential interference contrast. (B, E, H, K) CFP fluorescence (cyan) of the same fields shows that all of the STIM1 fusions are recruited to the plasma membrane after depletion of Ca2+ stores with 2 μM thapsigargin. (C) Lack of specific staining by HisZiFiT (yellow) indicates absence of extracellularly exposed His6-tags on the same cells as in B. (F) Lack of antibody staining for His5 (magenta) confirms absence of extracellularly exposed His6 tags on the same live cell as in E. (I) Surface exposed His6-tags of the same cell as in H are labeled by HisZiFiT (yellow). (L) Live cell His5-Ab staining (detected with Alexa Fluor 568-labeled secondary Ab, magenta) confirms the exposure of N-terminal His6-tags on the same cells as in K. Exposure times with a 5% neutral density filter on excitation were 200, 1,000, and 50 ms for CFP, HisZiFiT, and Alexa Fluor 568, respectively. Cartoons show schematically how His6 remains luminal in His6-CFP-STIM1 (B, C, E, and F) but becomes extracellularly accessible in His6-STIM1-CFP (H, I, K, and L).

Discussion

HisZiFiT is the first small-molecule chelator that binds to His6 sequences using nontoxic Zn2+ in place of Ni2+. Ni2+ is an acute blocker of Ca2+ channels and a chronic toxin, allergen, mutagen, and human carcinogen (9–11). Although these long-term pathologies need not affect short-term experiments on cultured cells, we see no advantages for Ni2+. Previous His6-binding dyes used on cells (5, 6) have contained single Ni2+-NTA units, so their affinities for His6 were quite modest, 2–12 μM KD. Dyes with two Ni2+-NTA units have tighter affinities as expected, 0.06–1 μM, but have not been demonstrated on cells (4, 7). The KD of Zn2+-loaded HisZiFiT for His6 (40 nM) is better yet, perhaps because the fluorescein scaffold rigidly holds the two Zn2+-binding sites in fairly close proximity, whereas the long floppy arms that connect NTA units in previous designs may reduce intramolecular cooperativity between the two Ni2+ ions. The diamagnetism of Zn2+ allows HisZiFIT to remain robustly fluorescent when Zn2+-bound, whereas paramagnetic Ni2+ quenches nearby fluorophores (5, 6). Nonfluorescent Ni2+-dye complexes are invisible on their own and have only been detected by their ability to quench neighboring FPs by FRET (5).

HisZiFiT is chemically orthogonal and functionally complementary to tetracysteine/biarsenical labeling (Fig. 3). HisZiFiT is naturally redox-independent and specific for cell surface tags, whereas tetracysteines are best suited to the reducing environment of the cytosol or nucleus. Restriction of labeling to surface-expressed tetracysteines is possible, but requires temporary reduction of disulfides with a membrane-impermeant reducing agent plus a sulfonated biarsenical (27), which is not commercially available. Tetracysteine/biarsenical labeling displays much higher affinity (KD values in the low pM range or lower) but much slower on and off rates. Just as tetracysteine sequences and biarsenical dyes have benefited greatly from multiple rounds of improvement (26, 27), the His6 sequence and HisZiFiT should be similarly optimized to provide tighter binding, increased photostability, decreased background staining, and additional wavelengths. Eventually it may become possible to label intracellular histidine-rich sequences, because it should be possible to synthesize membrane-permeant versions of HisZiFiT and Zn2+ can be separately delivered with ionophores (12). Another conceivable application would be to provide a prolonged mark at sites of endogenous Zn2+ release as in glutamatergic synapses or insulin-secreting beta cells.

The results with STIM1 (Fig. 4) exemplify the two major advantages of the His6-Zn2+-HisZiFiT system over previous fusions, the much smaller size of the peptide tag and the ability to distinguish surface-exposed proteins from those docked to the cytosolic face of the PM. The controversy over surface exposure of STIM1 is partially resolved by the findings that externalization of the N terminus of STIM1 is prevented by N-terminal fusions of HA tags, FPs, and horseradish peroxidase (41, 238, and >300 residues, respectively) but tolerates N-terminal His6 tags and C-terminal FP fusion. Anti-His5 antibody staining confirmed these HisZiFiT results. Although the antibody gave lower background signal, immunostaining is a slower, more complex, and less reversible procedure than HisZiFiT staining. Furthermore, antibodies promote lateral aggregation, add far more mass, and are known to perturb STIM1 function, possibly by dominantly modifying multimerization (17). Further studies will be required to quantify how much and how quickly surface exposure may increase upon stores depletion. We do not know the precise mechanism by which the N terminus of STIM1 moves from the ER lumen to the extracellular space. A prime candidate would be exocytotic fusion of vesicles budded off from the ER, consistent with observations that Ca2+ influx due to stores depletion can be inhibited by interference with proteins involved in exocytosis (28, 29). However, such exocytosis would differ from classical regulated secretion with respect to source organelle (ER vs. acidic secretory granules), mode of triggering by Ca2+ (luminal depletion vs. cytosolic elevation), and tolerance for luminal FP fusions (nonpermissive vs. permissive; ref. 30). Externalization of the N terminus of STIM1 is probably not essential for triggering Ca2+ influx, because overexpression of the nonexternalizing YFP-STIM1 fusion is sufficient to increase influx (15, 19). Presumably the activating interaction is the docking of the cytosolic C terminus of STIM1 to the PM, in particular the cytoplasmic domain of Orai1/CRACM1 (16, 18, 19). Externalization of the N terminus should expose the EF hand of STIM1 to the normally high levels of extracellular Ca2+, which could have additional signaling consequences. Investigation of this and many other instances of trafficking to and from the PM should be facilitated by the development of labels, such as HisZiFiT, that rapidly highlight very small, minimally perturbative protein tags.

Materials and Methods

The synthesis of the HisZiFiT dye, surface plasmon resonance experiments, and detailed cloning information with the final peptide sequences of the STIM1-containing constructs are described in SI Text.

HEK293T cells were plated onto sterilized glass coverslips on 2-cm imaging dishes and grown to 50–80% confluency in DMEM (GIBCO-BRL) supplemented with 10% FBS and 5% penicillin/streptomycin at 37°C in 6% CO2. Cells were transfected with FUGENE-6 transfection reagent (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After a 24- to 48-h incubation at 37°C in culture medium, the cells were washed twice with HBSS supplemented with 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.4) and 1 g/liter d-glucose before staining. His6-CFP-GPI-expressing cells were stained by adding ≈100 nM HisZiFiT (aliquots of 1 mM DMSO stock, ε = 72,000 mol−1 cm−1) in labeling buffer with 1 μM free Zn2+ (Zn2+ buffered by 8.099 mM l-histidine, 2.603 mM ZnO in 10 mM Hepes, 5 mM KCl, 140 mM NaCl, pH 7.4). See SI Text for details on Zn2+ buffers. After 1 min, the cells were washed twice with HBSS and imaged. Orthogonal staining of Connexin43–4C and His6-CFP-GPI-expressing cells was achieved by staining with 1 μM ReAsH/10 μM ethanedithiol (EDT) in HBSS for 30 min. Staining was followed by two 10-min washes with 0.1 mM 2,3-dimercaptopropanol in HBSS and 1 min of HisZiFiT staining as described above.

Cells expressing STIM1 fusions were stained and imaged 48 h after transfection. The culture medium was removed, and the cells were rinsed once with HBSS and a second time with Ca2+-free saline (25 mM Hepes, 140 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM d-glucose, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4). Before staining, Ca2+ store depletion was triggered by addition of 2 μM thapsigargin in Ca2+-free medium. The associated STIM1 plasma membrane translocation of the CFP-fusion proteins was monitored with CFP fluorescence. After ≈15 min, no further translocation was observed. The cells were washed twice with 2 ml of HBSS and stained by treating either with ≈100 nM HisZiFiT/1 μM Zn2+ staining solution as described above or with penta-His-antibody (mouse IgG1, Qiagen). An aliquot of the penta-His-antibody (His5-Ab) stock solution (0.2 mg/ml) was diluted 1:40 into DMEM with 10% FBS and added to the cells for 15 min. For visualization of the His5-Ab, the cells were washed twice with HBSS and stained for 15 min with a 1:300 dilution of secondary Ab stock solution (Alexa Fluor-568 goat anti-mouse IgG3, 2 mg/ml; Invitrogen) into DMEM/10% FBS. After secondary Ab staining, cells were washed two times with HBSS and imaged. Ab staining was highly specific to transfected cells, and control dishes stained with secondary Ab alone did not exhibit staining.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank B. N. G. Giepmans, S. R. Adams, P. Steinbach, O. Tour, and A. E. Palmer for helpful discussion, P. Steinbach for help with figure preparation, L. A. Gross and P. Dorrestein for mass spectrometry, and T. Meyer (Stanford University, Stanford, CA) for gifts of SP-CFP-GPI, SP-YFP-STIM1, and SP-CFP-STIM1 plasmids. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants NS27177 and GM72033 and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Abbreviations

- FP

fluorescent protein

- PM

plasma membrane

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- HisZiFiT

histidine-zinc fluorescent in vivo tag

- GPI

glycosylphosphatidylinositols.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0611713104/DC1.

References

- 1.Giepmans BN, Adams SR, Ellisman MH, Tsien RY. Science. 2006;312:217–224. doi: 10.1126/science.1124618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen I, Ting AY. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2005;16:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Griffin BA, Adams SR, Tsien RY. Science. 1998;281:269–272. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5374.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kapanidis AN, Ebright YW, Ebright RH. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:12123–12125. doi: 10.1021/ja017074a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guignet EG, Hovius R, Vogel H. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:440–444. doi: 10.1038/nbt954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldsmith CR, Jaworski J, Sheng M, Lippard SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:418–419. doi: 10.1021/ja0559754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lata S, Reichel A, Brock R, Tampe R, Piehler J. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:10205–10215. doi: 10.1021/ja050690c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meredith GD, Wu HY, Allbritton NL. Bioconjug Chem. 2004;15:969–982. doi: 10.1021/bc0498929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valko M, Morris H, Cronin MT. Curr Med Chem. 2005;12:1161–1208. doi: 10.2174/0929867053764635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Denkhaus E, Salnikow K. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2002;42:35–56. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(01)00214-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kasprzak KS, Sunderman FW, Jr, Salnikow K. Mutat Res. 2003;533:67–97. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2003.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walkup GK, Burdette SC, Lippard SJ, Tsien RY. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:5644–5645. doi: 10.1021/ja010059l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang SL, Yu Y, Roos J, Kozak JA, Deerinck TJ, Ellisman MH, Stauderman KA, Cahalan MD. Nature. 2005;437:902–905. doi: 10.1038/nature04147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roos J, DiGregorio PJ, Yeromin AV, Ohlsen K, Lioudyno M, Zhang S, Safrina O, Kozak JA, Wagner SL, Cahalan MD, et al. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:435–445. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200502019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liou J, Kim ML, Heo WD, Jones JT, Myers JW, Ferrell JE, Jr, Meyer T. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1235–1241. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.05.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soboloff J, Spassova MA, Tang XD, Hewavitharana T, Xu W, Gill DL. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:20661–20665. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600126200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spassova MA, Soboloff J, He LP, Xu W, Dziadek MA, Gill DL. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:4040–4045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510050103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peinelt C, Vig M, Koomoa DL, Beck A, Nadler MJ, Koblan-Huberson M, Lis A, Fleig A, Penner R, Kinet JP. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:771–773. doi: 10.1038/ncb1435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mercer JC, Dehaven WI, Smyth JT, Wedel B, Boyles RR, Bird GS, Putney JW., Jr J Biol Chem. 2006;281:24979–24990. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604589200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu MM, Buchanan J, Luik RM, Lewis RS. J Cell Biol. 2006;174:803–813. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200604014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manji SS, Parker NJ, Williams RT, Van Stekelenburg L, Pearson RB, Dziadek M, Smith PJ. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1481:147–155. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(00)00105-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lopez JJ, Salido GM, Pariente JA, Rosado JA. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:28254–28264. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604272200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Skulnick HI, Johnson PD, Aristoff PA, Morris JK, Lovasz KD, Howe WJ, Watenpaugh KD, Janakiraman MN, Anderson DJ, Reischer RJ, et al. J Med Chem. 1997;40:1149–1164. doi: 10.1021/jm960441m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keller P, Toomre D, Diaz E, White J, Simons K. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:140–149. doi: 10.1038/35055042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tour O, Meijer RM, Zacharias DA, Adams SR, Tsien RY. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:1505–1508. doi: 10.1038/nbt914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sosinsky GE, Nicholson BJ. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1711:99–125. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adams SR, Campbell RE, Gross LA, Martin BR, Walkup GK, Yao Y, Llopis J, Tsien RY. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:6063–6076. doi: 10.1021/ja017687n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yao Y, Ferrer-Montiel AV, Montal M, Tsien RY. Cell. 1999;98:475–485. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81976-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang SL, Yeromin AV, Zhang XH, Yu Y, Safrina O, Penna A, Roos J, Stauderman KA, Cahalan MD. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:9357–9362. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603161103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miesenbock G, Kevrekidis IG. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2005;28:533–563. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.051804.101610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.