Abstract

Objective

To develop a three-dimensional virtual model of a human temporal bone based on serial histologic sections.

Background

The three-dimensional anatomy of the human temporal bone is complex, and learning it is a challenge for students in basic science and in clinical medicine.

Methods

Every fifth histologic section from a 14-year-old male was digitized and imported into a general purpose three-dimensional rendering and analysis software package called Amira (version 3.1). The sections were aligned, and anatomic structures of interest were segmented.

Results

The three-dimensional model is a surface rendering of these structures of interest, which currently includes the bone and air spaces of the temporal bone; the perilymph and endolymph spaces; the sensory epithelia of the cochlear and vestibular labyrinths; the ossicles and tympanic membrane; the middle ear muscles; the carotid artery; and the cochlear, vestibular, and facial nerves. For each structure, the surface transparency can be individually controlled, thereby revealing the three-dimensional relations between surface landmarks and underlying structures. The three-dimensional surface model can also be “sliced open” at any section and the appropriate raw histologic image superimposed on the cleavage plane. The image stack can also be resectioned in any arbitrary plane.

Conclusion

This model is a powerful teaching tool for learning the complex anatomy of the human temporal bone and for relating the two-dimensional morphology seen in a histologic section to the three-dimensional anatomy. The model can be downloaded from the Eaton-Peabody Laboratory web site, packaged within a cross-platform freeware three-dimensional viewer, which allows full rotation and transparency control.

Keywords: Histologic section, Human temporal bone, Surface rendering, Three-dimensional reconstruction

The human temporal bone contains a large number of complex structures within a small space. The three-dimensional anatomy of the human temporal bone can be challenging to grasp for students in the basic science or medical disciplines. Traditional tools and techniques of study use two-dimensional histologic sections and surgical dissections of actual temporal bones. A three-dimensional virtual model would be a valuable tool for learning the anatomy of the human temporal bone. Several investigators have developed three-dimensional (3-D) models of the human and animal inner ear using histologic or radiologic data. In some of the early work in this field, Sando et al. (1-3) developed computer-generated wire-frame models of various structures in the middle ear and inner year from tablet tracings of histologic sections. Takahashi and Sando (4) also developed a stereophotographic technique to display the reconstructed images in three dimensions. Harada et al. (5) and Green et al. (6) took different approaches by photographing or video recording the histologic sections and generating preliminary three-dimensional surface models of different anatomic structures. With the recent rapid development of processing power of modern computers and 3-D computer graphics technology, a variety of structures in the temporal bone have been reconstructed or measured using histologic sections (7-10). 3-D reconstructions using other methods of imaging the ear have also been explored. For example, Morra et al. (11) and Vrabec et al. (12) displayed inner ear and middle ear structures in three dimensions using computed tomography, whereas Voie (13) and Santi et al. (14) developed 3-D reconstructions of the mouse cochlea using orthogonal-plane fluorescence optical sectioning microscopic images. Hardie et al. (15) used fluorescent confocal microscopy to visualize the organ of Corti of the mammalian cochlea in 3-D. These various studies have undoubtedly served to advance the field of 3-D imaging of the mammalian temporal bone and have been quite useful for purposes of teaching. However, many of these models have certain technical limitations. For instance, the models often consist of reconstruction of specific anatomic structures such as the cochlea or semicircular canals, but they do not readily depict the spatial orientation of the anatomic structures within the bony confines and air spaces of the human temporal bone. Also, user interaction in the 3-D model is often limited in its scope and degree.

In this study, we used a commercially available software package called Amira (Mercury Computer Systems/TGS, San Diego, CA, U.S.A.), that is relatively easy to use yet powerful and versatile in its capabilities to develop a 3-D model of the human temporal bone using histologic sections. Amira has a user-friendly interface and tools that allow automation or semiautomation of many aspects of 3-D reconstruction. Our reconstruction contains 25 surface models of different anatomic structures from the human external ear, middle ear, inner ear, and the surrounding bone. The model can be rotated in any angle using simple mouse controls. Each structure can be viewed either individually or together with some or all of the other structures. Users can control the degree of transparency of each structure so that overlapping structures can be viewed with ease. The 3-D surface models can be “sliced open” at any section and the appropriate raw histologic image can be superimposed on the cleavage plane. We also developed a stand-alone, free 3-D viewer that has full rotation and transparency controls, which greatly enhances the accessibility and usability of the teaching model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Histologic Sections and Digitization

The model was created from archival histologic sections from a 14-year-old male. The specimen was fixed in formalin, decalcified using 5% trichloroacetic acid, embedded in celloidin, and serially sectioned in the axial plane at a thickness of 20 μm (16). Every fifth section through the temporal bone was stained with hematoxylin and eosin and mounted on glass slides, resulting in 141 stained sections. Each stained section was digitized using a Nikon Super Cool Scan 4000 ED at resolution of 5,590 × 3,473 pixels. The size of each color image was approximately 60 MB, and the size of the stack of 141 sections was approximately 8.5 GB. The color images were converted into gray scale, and the resolution of each image was reduced to 1,397 × 868 pixels, which diminished the size of the image stack to approximately 170 MB, enabling us to fit the complete image stack into the memory of our workstation. The digitized sections were then imported into Amira 3.1.

Alignment

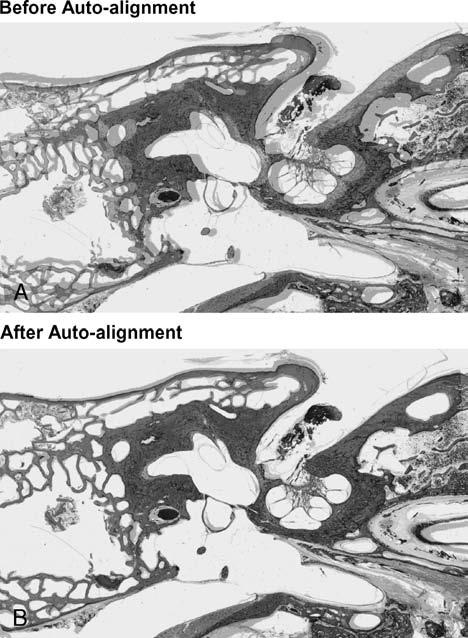

The digitized two-dimensional (2-D) sections were then registered pair by pair using Amira's interactive alignment tool. Every two consecutive sections were displayed simultaneously with half opacity (Fig. 1A). The pair was auto-aligned by Amira's “quality function optimization method,” which was a “least square best fit” algorithm computed from minimizing the squared gray-scale value differences of the pixels in the two consecutive slices (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Alignment: a pair of consecutive sections displayed before (A) and after (B) auto-alignment was performed using Amira's automated tool for auto-registering.

Segmentation

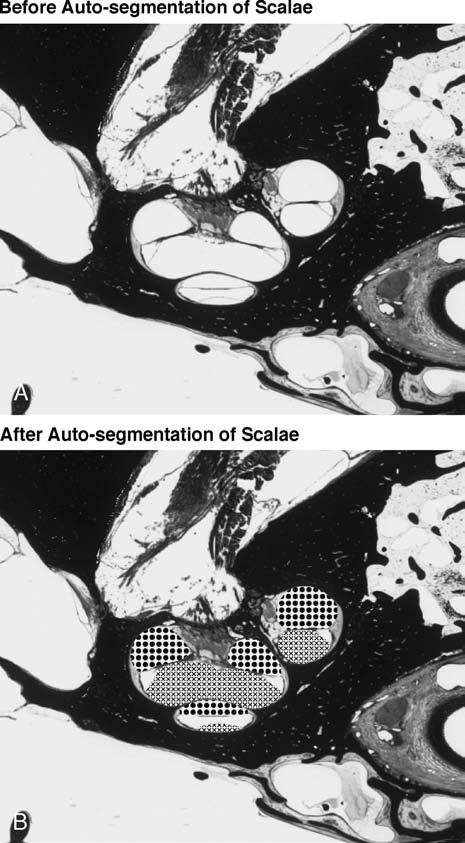

Once all the two-dimensional sections were aligned, anatomic structures of interest were extracted using the semiautomated segmentation tools provided by Amira, such as “thresholding,” “lasso,” “magic wand,” “contour fitting,” and others, as well as using various filters including “smoothing,” “cleaning,” and “connected component analysis.” These tools significantly simplified and accelerated the otherwise tedious process of segmentation (i.e., outlining the various structures of interest). Figure 2 shows the semiautomated segmentation of the cochlear scalae using the magic wand function. It was difficult to segment some structures such as the basilar membrane and the endolymphatic sac using the semiautomated tools provided by Amira. A manual technique was used to outline and segment these structures.

FIG. 2.

Automated segmenting of cochlear scalae using the magic wand function of Amira. The cross pattern in (B) shows the scala vestibuli and the dotted pattern is the scala tympani.

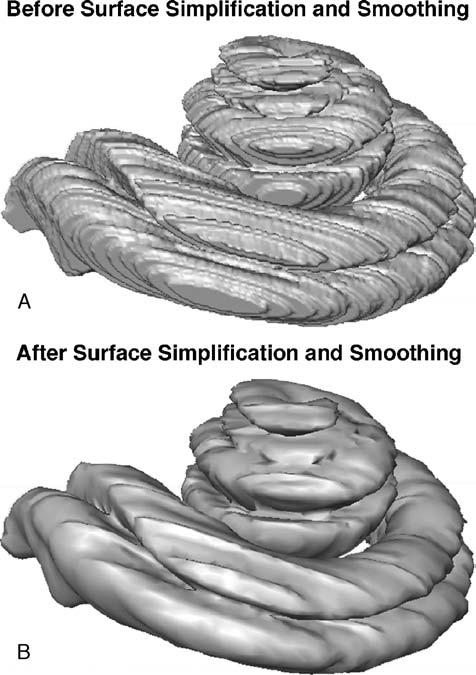

Surface Reconstruction, Simplification, and Smoothing

After the anatomic structures of interest were segmented, polygonal surface models were generated that were topologically correct (i.e., free of self-intersection). Amira's “simplification” algorithm was then applied to these surface models that removed redundant vertices and made the models smooth by reducing the number of triangles in each model. Amira allows users to specify the number of iterations desired for the smoothing algorithm, which smoothes the surface models by shifting each vertex toward the average position of its neighboring vertices. Two to five iterations of the smoothing algorithm were applied to each surface. Figure 3 compares surface models of the scala tympani and scala vestibuli before and after simplification and smoothing.

FIG. 3.

Surface models of the scala tympani and the scala vestibuli before (A) and after (B) application of algorithms for surface simplification and smoothing.

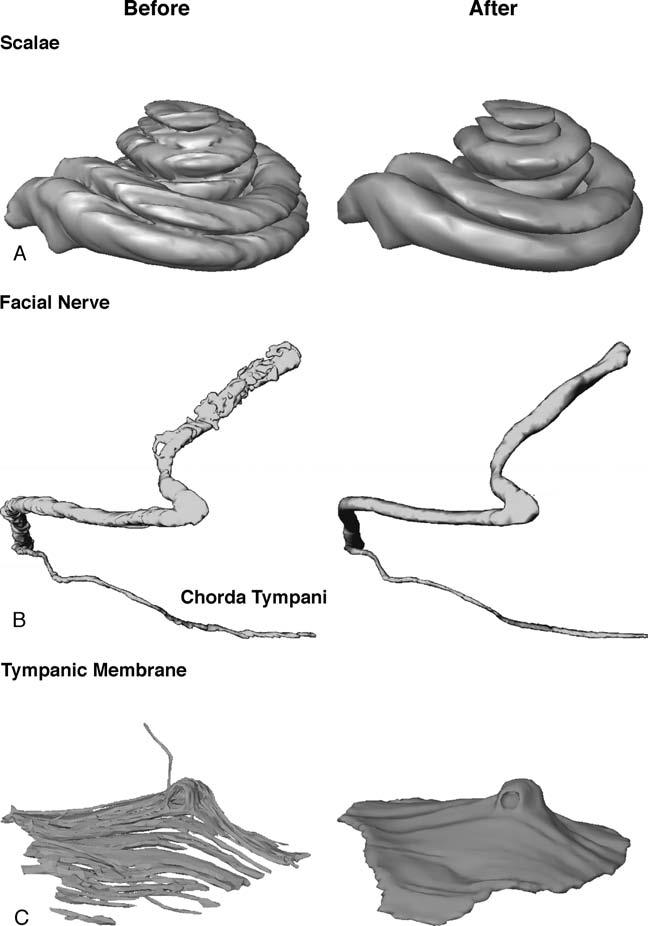

Surface Refinement: Interpolation

Slight degrees of mechanical distortion are inevitably introduced as a temporal bone is sectioned and the individual sections are mounted on glass slides. These distortions include stretching or folding of parts of a section, and they result in artifactual distortions of the reconstructed surface model of a given anatomic structure. We used the technique of “interpolation” to overcome this problem. For example, if section n was distorted, it was not segmented; rather, it was replaced by an interpolation between data from section n + 1 and n – 1. The amount of interpolation needed varied among different structures. As shown in Figure 4, there were few distortions in the initial rendering of the scalae (Fig. 4A); thus, only a small number of interpolations were required. The facial nerve (Fig. 4B), and tympanic membrane (Fig. 4C) had many more distortions. A large number of interpolations were necessary to smooth the surface rendering of these two structures.

FIG. 4.

Surface models of the scalae (A), facial nerve (B), and tympanic membrane (C) before and after interpolation.

Estimates of Time Spent on Each Procedure

Although many features of the Amira software reduced the time required to create a 3-D model, 3-D reconstructions created from anatomic data such as ours are still time consuming. Creation of our 3-D virtual model took 2 to 3 person-months. Most of the time was spent on segmentation and surface refinement of some of the more difficult structures. The estimates of the time spent on each procedure were as follows: digitization, ∼1%; alignment, ∼1%; segmentation, ∼65%; surface generation, simplification, and smoothing, ∼2%; and surface refinement, ∼31%.

Creation of a 3-D Surface Viewer

Although Amira provides a user-friendly and powerful software environment to create 3-D models, it is expensive and thus not practical for wide distribution for purposes of teaching. To increase the accessibility of our teaching model, we developed a stand-alone, downloadable, cross-platform software, the 3-D Surface Viewer. This software was developed in C++ using OpenGL (17) technology and FLTK (18) (Fast Light Toolkit, an open source toolkit for GUI development). Cross-platform compilation was made possible using OpenGL and FLTK. The 3-D Surface Viewer can be installed on Windows XP/2000, Mac OS X, and Linux Red Hat 9, and can be downloaded from our web site at http://epl.meei.harvard.edu/∼hwang/3Dviewer/3Dviewer.html

RESULTS

The final teaching model is an anatomically realistic human temporal bone that contains many of the important structures. The structures are hierarchically organized into five groups on the basis of their anatomy:

The external ear group: the external auditory canal and tympanic membrane.

The middle ear group: the malleus, incus, stapes, ossicular ligaments, middle ear muscles, and the eustachian tube.

The inner ear group: the bony semicircular canals, scala tympani, scala vestibuli, membranous labyrinth, cochlear aqueduct, round window membrane, vestibular sense organs, and the basilar membrane.

The nerves group: the cochlear and vestibular nerves, facial nerve including chorda tympani, and the internal auditory canal.

The bone with great vessels group: the otic capsule, middle ear and mastoid air spaces, petrous apex, carotid artery, and jugular vein.

Our model does not contain the most superior part of the anatomy of the temporal bone, above the level of the ampulla of the superior semicircular canal, as these histologic sections were discarded during the processing of the temporal bone. The 3-D models of these anatomic structures can be displayed in Amira as shaded smooth surfaces with full rotation and transparency control. Morphologic measurements can be easily made using the measurement tools provided by Amira. Amira also provides an interface to slice open the 3-D surfaces and superimpose two-dimensional images in any given arbitrary plane. Solid volume models can also be made from the stack of histologic images.

The teaching model is packaged with the freeware 3-D Surface Viewer, which provides a user-friendly graphic interface to display 3-D surface models exported from Amira. In the 3-D Surface Viewer, users can rotate and zoom the 3-D models in real time using simple mouse controls. The visibility of each individual structure can be controlled and its degree of transparency can be adjusted (Fig. 5). To facilitate identification, each anatomic group is assigned a base color that is shown in the control panel, and all structures within a group comprise different shades of that base color. The two-dimensional raw histologic images can be superimposed onto the 3-D models, and users can navigate the series of histologic images in different planes (Fig. 6). The ability to make morphologic measurements and to virtually reslice in any arbitrary plane are features that are not available in the 3-D Surface Viewer. Because the freeware 3-D Surface Viewer can display any 3-D surface model exported from Amira, it can serve as a tool to display our model and can also be used by other research groups performing similar 3-D reconstructions.

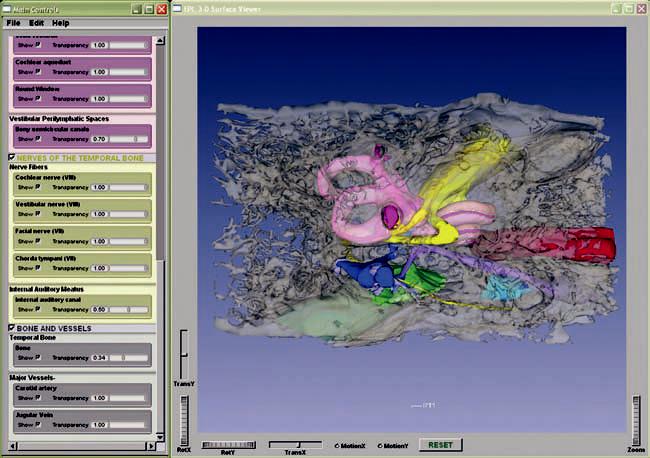

FIG. 5.

A screenshot of the 3-D Surface Viewer with a subset of anatomic structures visible through bone that has been rendered semitransparent.

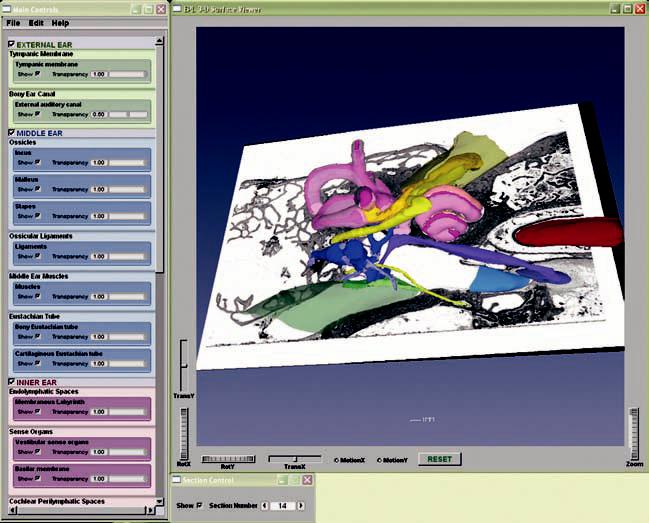

FIG. 6.

A screenshot of the 3-D Surface Viewer with an image of a histologic section mapped into a set of surface contours.

DISCUSSION

Our 3-D virtual model of the human temporal bone provides a teaching tool for students in the basic science and clinical disciplines that delivers realistic, interactive, anatomic information with 3-D visualization. Morphologic measurements such as distance, area, and volume can be made using the virtual model in Amira. It can also aid in surgical planning by helping the otologic surgeon to understand the complex spatial relationships of various anatomic structures contained within the temporal bone. Additional models can be created to depict the effects of otologic disease in three dimensions (e.g., cholesteatoma, acoustic neuroma, congenital aural atresia).

There are also several areas for improvement in the future. The present model was created using every fifth histologic section through the temporal bone. One could improve on the resolution of anatomic detail by staining every section and using all sections for the 3-D reconstruction. As previously discussed, much of the superior semicircular canal is missing from our model. In the future, efforts could be made to preserve the most superior sections during histologic preparation of the specimen. One could also improve the correctness of alignment and reduce the number of distortions by photographing the temporal bone while it is on the cutting block before each section is cut. The freeware 3-D Surface Viewer also has room for future refinement. For example, the current version of the viewer only accepts a certain type of Virtual Reality Modeling Language file. To broaden the usability of this software, one could expand the number of file formats it can accept as input. Some other features such as picking and labeling in three dimensions could also be added.

Footnotes

This project was supported by a core grant from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (P30 DC05209) and by the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders National Temporal Bone, Hearing and Balance Pathology Research Registry (N01-DC-4-0001).

REFERENCES

- 1.Takagi A, Sando I. Computer-aided three-dimensional reconstruction and measurement of the vestibular end-organs. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1988;98:195–202. doi: 10.1177/019459988809800303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takagi A, Sando I, Takahashi H. Computer-aided three-dimensional reconstruction and measurement of semicircular canals and their cristae in man. Acta Otolaryngol. 1989;107:362–5. doi: 10.3109/00016488909127522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nakashima S, Sando I, Tkahashi H, et al. Computer-aided 3-D reconstruction and measurement of the facial canal and facial nerve: I. cross-sectional area and diameter: preliminary report. Laryngoscope. 1993;103:1150–6. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199310000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takahashi H, Sando I. Stereophotography of computer-aided three-dimensional reconstructions of the temporal bone structures. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;106:110–3. doi: 10.1177/019459989210600139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harada T, Ishii S, Tayama N. Three-dimensional reconstruction of the temporal bone from histologic sections. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1988;114:1139–42. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1988.01860220073027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Green JD, Jr, Marion MS, Erickson BJ, et al. Three-dimensional reconstruction of the temporal bone. Laryngoscope. 1990;100:1–4. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199001000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mason TP, Applebaum EL, Rasmussen M, et al. Virtual temporal bone: creation and application of a new computer based teaching tool. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;122:168–73. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(00)70234-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arnold WH, Lang T. Development of the membranous labyrinth of human embryos and fetuses using computer aided 3D-reconstruction. Ann Anat. 2001;183:61–6. doi: 10.1016/S0940-9602(01)80014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rother T, Schrock-Pauli C, Karmody CS, et al. 3-D reconstruction of the vestibular endorgans in pediatric temporal bones. Hear Res. 2003;185:22–34. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(03)00255-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qiu MG, Zhang SX, Liu ZJ, et al. Plastination and computerized 3D reconstruction of the temporal bone. Clin Anat. 2003;16:300–3. doi: 10.1002/ca.10076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morra A, Tirelli G, Rimondini V, et al. Usefulness of virtual endoscopic three-dimensional reconstructions of the middle ear. Acta Otolaryngol. 2002;122:382–5. doi: 10.1080/00016480260000058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vrabec JT, Champion SW, Gomez JD, et al. 3D CT imaging method for measuring temporal bone aeration. Acta Otolaryngol. 2002;122:831–5. doi: 10.1080/0036554021000028085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Voie AH. Imaging the intact guinea pig tympanic bulla by orthogonal-plane fluorescence optical sectioning microscopy. Hear Res. 2002;171:119–28. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(02)00493-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Santi P, Blair A, Pham V, et al. The mouse cochlea database: high resolution 3D reconstructions of the mouse cochlea; Presented at the 27th Midwinter Meeting of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology; Daytona Beach, FL. February 21–26, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hardie NA, MacDonald G, Rubel EW. A new method for imaging and 3D reconstruction of mammalian cochlea by fluorescent confocal microscopy. Brain Res. 2004;1000:200–1. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.10.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schuknecht HF. Pathology of the Ear. 2nd ed. Lea & Febiger; Philadelphia, PA: 1993. pp. 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- 17. OpenGL [web site]. Available at: www.OpenGL.org. Accessed January 11, 2005.

- 18. Fast Light Toolkit [web site]. Available at: www.fltk.org. Accessed January 11, 2005.