Abstract

Activation of the endothelin receptor B (ETRB) in cultured melanocyte precursors promotes cell proliferation while inhibiting differentiation, two hallmarks of malignant transformation. We therefore tested whether ETRB has a similar role in malignant transformation of melanoma. When tested in culture, we find that the selective ETRB antagonist BQ788 can inhibit the growth of seven human melanoma cell lines, but not a human kidney cell line. This inhibition often is associated with increases in pigmentation and in the dendritic shape that is characteristic of mature melanocytes. In three cell lines we also observe a major increase in cell death. In contrast, the endothelin receptor A (ETRA) antagonist BQ123 does not have these effects, although all the cell lines express both ETRA and ETRB mRNA. Extending these studies in vivo, we find that administration of BQ788 significantly slows human melanoma tumor growth in nude mice, including a complete growth arrest in half of the mice treated systemically. Histological examination of tumor sections suggests that BQ788 also enhances melanoma cell death in vivo. Thus, ETRB inhibitors may be beneficial for the treatment of melanoma.

Cells in the early embryo and cells in advanced stages of malignant transformation can share common features such as a high rate of proliferation and/or lack of contact inhibition and a low degree of differentiation. In the case of melanocytes, the c-kit receptor and its ligand Steel are active at a relatively advanced stage in melanocyte precursor development and are essential for the survival and differentiation of these cells (1, 2). The function of these signaling molecules is lost gradually during melanoma transformation, and enforced c-kit expression can induce melanoma cells to differentiate (3). Similarly, other growth factors and receptors that are involved in normal melanocyte development (4) are thought to play a similar role in melanoma transformation (5).

Human melanocyte precursors fail to develop properly in individuals with mutations in the gene encoding endothelin receptor B (ETRB), a syndrome known as Hirschsprung’s disease (6). Similarly, mice develop pigmentation abnormalities (spotting) when either ETRB or its ligand endothelin 3 (ET3) do not function during embryonic development (7, 8). In culture, ET3 enhances the proliferation and delays the differentiation of melanocyte precursors (9, 10), an effect correlated with increased expression of ETRB (11). Such findings led us to hypothesize that ETRB also could be involved in melanoma growth. Indeed, all human melanoma lines tested so far express ETRB (12–15), and expression is correlated with their differentiation state. Increased ETRA expression, in contrast, is associated with induced differentiation of A375 melanoma cells, whereas ETRB is expressed predominantly in the malignant state (14). Although one report indicates that ET1, acting through ETRB, mediates mitogenic and chemokinetic effects on cultured melanoma cells (12), another report suggests that the same ligand–receptor system slows growth and induces apoptosis when A375 cells are synchronized (16). Because the specific ETRB inhibitor BQ788, a modified peptide (17), antagonizes effects of ET3 on melanocyte precursors by reducing proliferation and increasing pigmentation (R.L., unpublished data), we tested this inhibitor on human melanoma cell growth in culture and in an in vivo tumor model in nude mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture.

Human melanoma cell lines were obtained from the American Tissue Culture Collection (ATCC) and were cultured with DMEM (ATCC) containing 10% FCS (Gemini Biological Products, Calabasas, CA), 2 mM glutamine (GIBCO/BRL), and 100 μg/ml antibiotics (Pen-Strep mix; GIBCO/BRL) in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 at 37°C. BQ788 and BQ123 (Calbiochem) were dissolved in 2% polyoxythylene (60)-hydrogenated castor oil (HCO60; Nikko Chemicals, Tokyo). Cells were cultured in 96-well ELISA plates (Falcon). For the cell viability/cell number assay, the day after plating, inhibitor or vehicle was added and the cultures were incubated for 4 days. The MTS assay [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium, inner salt] was used to quantify cells by measuring OD at 492 nm (Promega). P values were calculated by using the Student’s t test for absolute values.

Reverse Transcription–PCR Analysis.

Total RNA was isolated from each cell line by using an RNA isolation kit (Promega). The cDNA was prepared from 10 μg total RNA using MMLV Reverse Transcriptase (GIBCO/BRL). Two micrograms of cDNA was used for each PCR. Primers and conditions were as described previously (18).

Immunohistochemistry.

Tumors were frozen on dry ice, cut into 20-μm sections on a cryostat, and stored at −80°C. Sections were rinsed in calcium- and magnesium-free PBS, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 1 hr at room temperature, blocked with 2% rabbit serum, and incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4°C. After washing in PBS, sections were incubated with a biotinylated secondary antibody, and staining was developed by using the Elite ABC kit (Vector Laboratories). The primary antibody used in this study was a monoclonal rat anti-mouse CD31 (platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule). The terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated UTP end labeling (TUNEL) staining kit was obtained from Boehringer Mannheim.

RESULTS

BQ788 Induces Signs of Differentiation and Reduces the Viability of Human Melanoma Cells in Vitro.

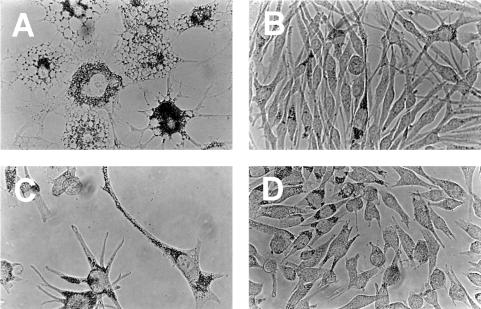

To test the hypothesis that ETRB function plays a role in melanoma cell growth and differentiation, we cultured seven human melanoma cell lines and a human kidney cell line with the highly selective ETRB antagonist BQ788 (17) (Novabiochem; N-cis-2,6-dimethylpiperidinocarbonyl-l-γ-MeLeu-d-Trp(MeOCO)-d-Nle-OH, sodium salt). Concentrations up to 100 μM were tested, because this was the highest dose at which strong specificity of the compound for ETRB was demonstrated previously (17). Inspection of the treated cultures reveals drastic morphological changes in some of the melanoma lines. As shown in Fig. 1 A and B, SK-MEL 28 cells develop large cytoplasmic vacuoles and enhanced pigmentation. Similar changes are seen with antagonist treatment of A375 and RPMI 7951 cells (not shown). All cell lines flatten significantly on the dish surface, and most (except SK-MEL 3) show major increases in pigmentation (Fig. 1). Treatment of SK-MEL 5 cells also results in a dendritic phenotype similar to that observed in normal, mature melanocytes (Fig. 1 C and D). In contrast, treatment of kidney 293 cells with BQ788 does not result in any morphological change (data not shown), demonstrating that this inhibitor does not cause such effects in all cell types.

Figure 1.

The ETRB antagonist BQ788 induces morphological changes in cultured melanoma cells. Cells were cultured for 4 days with 100 μM BQ788 (A and C) or with vehicle (B and D). The cell lines were melanoma line SK-MEL 28 (A and B) and melanoma line SK-MEL 5 (C and D). Note the different shape of the drug-treated melanoma cells and their accumulation of black pigment. Pictures were taken with bright-field optics at ×40 magnification.

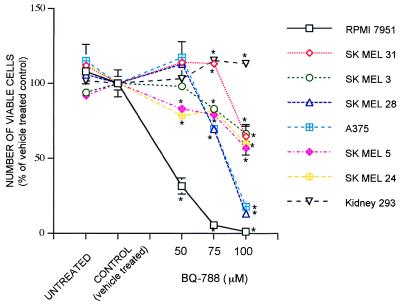

In addition to inducing morphological changes indicative of differentiation, treatment of the melanoma cells with BQ788 eventually results in reduced cell number and cell death. This effect was quantified by using the MTS assay. As shown in Fig. 2, all seven melanoma lines show a significant loss in the number of viable cells upon treatment with 100 μM BQ788, although some lines are more sensitive than others. In contrast, the number of kidney cells is increased somewhat by high concentrations of BQ788, demonstrating that this inhibitor is not generally toxic.

Figure 2.

BQ788 reduces the number of viable cells in cultured melanoma but not kidney cells. Cells were cultured in the presence of the antagonist, vehicle, or with no treatment for 4 days. Three wells of each condition were subjected to the MTS assay. The mean values were calculated and plotted as the percentage of the vehicle-treated value ± SEM. The experiment was repeated three times, with similar results. BQ788 values are indicated by ∗ when significantly different from controls (P < 0.05).

To estimate how much of the decrease in viable melanoma cells is due to cell death, we evaluated the percentage of dying cells in drug-treated and control cultures. The results summarized in Table 1 show that some of the melanoma lines display a striking increase in TUNEL labeling with BQ788 treatment (13- to 40-fold more than controls). In contrast, other lines display no significant increase in TUNEL labeling, suggesting that the effect of BQ788 on these lines is primarily through inhibition of proliferation.

Table 1.

Treatment with BQ788 increases TUNEL staining in certain melanoma cell lines in culture

| Cell line | BQ788 | Control | Δx |

|---|---|---|---|

| RPMI 7951 | 76.4 ± 6.1 | 1.9 ± 1.1 | 40.2* |

| SK MEL 28 | 7.4 ± 1.6 | 0.4 ± 0.3 | 18.5* |

| A375 | 21.6 ± 5.4 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 13.5* |

| SK MEL 5 | 1.5 ± 1.3 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 3 |

| SK MEL 24 | 1.2 ± 0.5 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 2 |

| SK MEL 31 | 7.8 ± 1.6 | 3.5 ± 1.2 | 2.2 |

| SK MEL 3 | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 1.7 ± 1.1 | 0.8 |

| Kidney 293 | 2.8 ± 1.3 | 3.4 ± 0.2 | 0.8 |

TUNEL staining is expressed as percent positive cells after 4 days in culture in the presence of 100 μM BQ788 and compared with vehicle-treated cells as the control. Δx represents the fold increase; *P < 0.05. P for percent values was calculated by using the Mann–Whitney test (n = 3–5).

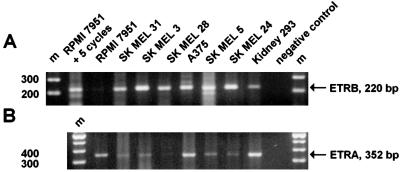

To verify that the cells express ETRB, we performed reverse transcription–PCR by using published primer sequences (18). All of these cell lines, including the kidney cells, display a band of the size expected for authentic ETRB mRNA (Fig. 3A). Five additional PCR cycles were required to detect this band in RPMI 7951 cells. In addition, all cell lines express ETRA (Fig. 3B). Similar findings on receptor expression in some of these lines have been reported previously (12, 14).

Figure 3.

Reverse transcription–PCR reveals the expression of ETRB and ETRA mRNA in all cell lines used. Bands corresponding to ETRB (A) (220 bp) and ETRA (B) (352 bp) mRNAs were obtained by using published primer sequences and protocols (18). For the cell line RPMI 7951, an additional five PCR cycles were needed to obtain a strong band for the ETRB shown in A. Molecular weight markers (m) are shown in the outer lanes of the gel near the negative controls, in which the cDNA was omitted.

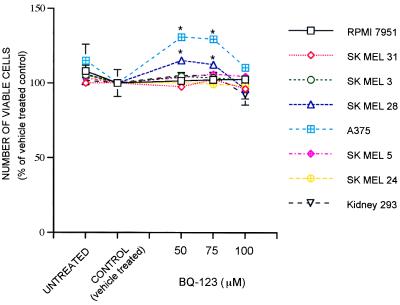

The coexpression of ETRA allowed us to examine the effect of adding the selective ETRA antagonist BQ123 (19) to these cells. As shown in Fig. 4, BQ123 does not reduce the number of viable cells in any of the cell lines, even at high concentration. In fact, this antagonist slightly increases cell number in two of the melanoma lines, A375 and SK-MEL 28. Thus, the effects of BQ788 at high concentration are not mediated through ETRA.

Figure 4.

The selective ETRA antagonist BQ123 does not reduce the number of viable melanoma cells in culture. Conditions and presentation are as described for the BQ788 experiment shown in Fig. 2.

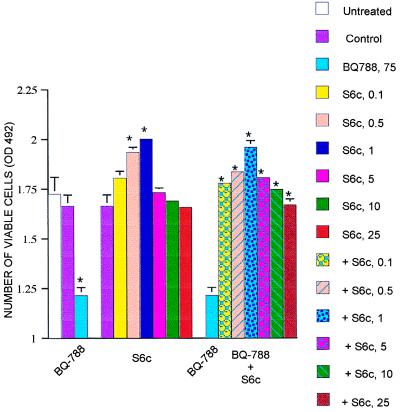

To examine further the effect of BQ788, we used the highly selective ETRB agonist, sarafotoxin 6c (S6c) (20). As predicted, at concentrations of 0.1–1 μM, S6c increases A375 cell number (Fig. 5). Importantly for the present experiments, S6c completely blocks the effects of BQ788 on A375 cells (Fig. 5). Thus, the ability of BQ788 to lower melanoma cell number is likely to be through its action on ETRB and not as a side effect on another aspect of melanoma cell physiology.

Figure 5.

An ETRB-selective agonist abrogates the effects of BQ788 on melanoma cells. In experiments similar to those illustrated in Fig. 2, S6c (0.1–25 μM) was tested for its effects on A375 cells cultured for 4 days alone or in combination with BQ788 (75 μM). The ETRB agonist stimulates cell growth and blocks the inhibitory effect of the ETRB antagonist. The means of absolute values (n = 3–5) were calculated ± SEM and plotted. P values were calculated by using the Student’s t test and are indicated by ∗ when significantly different (P < 0.05) from controls or in comparison with BQ788 values when the addition of S6c to BQ788 was tested.

These results provide the first indication that an ETRB antagonist can impair melanoma cell viability in culture and suggest the possibility of using such drugs to inhibit the growth of melanoma tumors in vivo.

BQ788 Inhibits Human Melanoma Growth in Nude Mice.

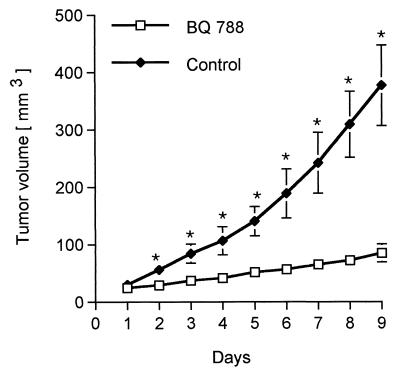

For the in vivo experiments we chose the A375 melanoma cell line. Although this line is not the most sensitive to BQ788 treatment in culture, it is known to grow readily in nude mice. First, dissociated cells were injected as a suspension into the flanks of nude mice. When tumors developed, they were excised, cut into pieces of approximately 3 mm in diameter, and implanted under the skin of a new series of nude mice. When a tumor reached 4 mm in diameter (which takes approximately 12 days), 25 μl of a solution containing 20 μg/μl BQ788 dissolved in 2% HCO60 (17) was injected into the tumor daily for 9 days. This dose was chosen based on a clinical trial by Haynes et al. (22), who studied the effect of a nonselective ETR antagonist on blood pressure in healthy volunteers, where no significant side effects were observed. In this trial the highest dose was of 1000 mg, which we estimate would correspond approximately to a dose of 0.5 mg/mouse. Tumors in control mice were injected in the same way, with 25 μl of 2% HCO60. Before each injection the tumor dimensions were measured with calipers. Tumor volume was calculated as length × width2 × 0.5. Results from three experiments, using a total of 10 BQ788-treated mice and 8 vehicle-treated mice, are shown in Fig. 6. At the outset, the mean tumor volume was 26 mm3 in both control and BQ788-treated mice. After 9 days the mean tumor volume of the control group reached 376 mm3 whereas the BQ788-treated group had a mean tumor volume of 84 mm3. Calculation of the growth rate (final size minus initial size/time) reveals that the BQ788-treated tumors grow six times slower than control tumors. Similar conclusions come from comparison of tumor weights (means of 446 mg vs. 93 mg; P < 0.005).

Figure 6.

Intratumor injection of BQ788 inhibits melanoma tumor growth in nude mice. Nude mice (nu/nu, BALB/c background) were implanted with grafts of A375 cells s.c. in the flank. After the tumors had reached approximately 4 mm in diameter they were injected daily with BQ788 for 9 days. Perpendicular tumor diameters were measured daily to estimate tumor volume. Controls were injected on the same schedule with vehicle. Data from three experiments using 10 BQ788-treated mice and 8 vehicle-treated mice are pooled. P values were calculated by using the Student’s t test and are indicated by ∗ when significantly different from controls (P < 0.05). Similar conclusions come from measuring tumor weights, as described in the text.

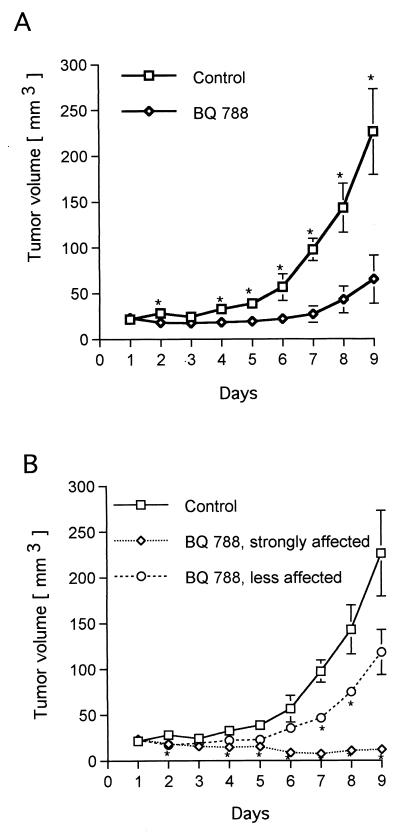

Although these results encourage the idea that ETRB inhibitors may prove useful in controlling melanoma growth in vivo, intratumor drug delivery is not the most clinically relevant approach if tumors have spread. Therefore, we asked whether systemic administration of BQ788 also inhibits tumor growth. In these experiments, tumor induction and the starting point of the treatments were as for the intratumor experiments. At that point, mice were injected with 100 μl of BQ788 solution (0.6 mg of BQ788 in 30% water and 70% saline, at a final HCO60 concentration of 0.6%) i.p. once or twice a day for a period of 9 days. Control mice received the same injections but without BQ788. In the first experiment, mice were injected once a day, and in the second experiment, the mice were injected in the morning and then again in the early evening. Because results from these two experiments did not differ, they were pooled and are presented in Fig. 7A. It is clear that systemic administration also results in effective inhibition of tumor growth. This graph, however, does mask an important heterogeneity in the response of the mice to BQ788. For the first 6 days, tumors in the BQ788 group did not differ significantly from their size at day 1. After 6 days, the BQ788 mice could be divided into two subgroups that responded differently to the drug, as shown in Fig. 7B. In one set of mice, BQ788 treatment slows tumor growth whereas in the other set of mice, the tumors shrink and display complete growth arrest.

Figure 7.

Systemic administration of BQ788 inhibits melanoma tumor growth in nude mice. The experiments were similar to those described in Fig. 6, except that the drug and vehicle were injected daily i.p. In A, the data for the six BQ788-treated mice were pooled. In B, separate curves are drawn for the data from the three mice in which BQ788 slowed tumor growth and for the data from the three mice in which BQ788 caused the tumors to regress. P values were calculated by using the Student’s t test and are indicated by ∗ when significantly different from controls (P < 0.05).

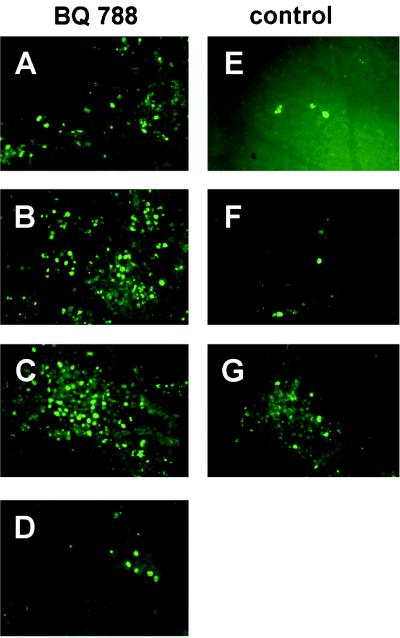

Several of the tumors from the i.p. injection experiment were taken for histological examination on day 10. Sections were stained with anti-CD31 antibody for angiogenesis and with the TUNEL method for apoptosis. In general, BQ-788 treatment results in enhanced TUNEL labeling (Fig. 8), suggesting that the drug increases melanoma cell apoptosis in vivo as well as in culture. Staining with the anti-CD-31 antibody to highlight blood vessels provided no evidence that BQ788 blocks angiogenesis (data not shown).

Figure 8.

TUNEL staining of A375 cell tumors grown in nude mice reveals evidence for BQ788-stimulated apoptosis. Representative sections are illustrated from four tumors from BQ788-injected (i.p.) mice and three tumors from vehicle-injected mice. TUNEL-positive cells are in most cases much more frequent in tumors from the drug-treated animals, suggesting enhanced apoptosis. (A–D) BQ788-treated mice. (A and B) Less-affected tumors. (C and D) Strongly affected tumors. (E–G) Vehicle-treated mice. Pictures were taken at ×20 magnification.

DISCUSSION

These results demonstrate that the ETRB inhibitor BQ788 is an effective agent for slowing or, in some cases, completely stopping human melanoma tumor growth in the nude mouse model. Although the mechanism of this effect is not yet clear, our culture experiments suggest that BQ788 slows melanoma cell growth, induces differentiation, and eventually causes cell death. The heterogeneity in the response of these melanoma lines to this inhibitor supports a model of progressive effects. The lines least affected by BQ788 (SK-MEL 3, 24, and 31) display flattening on the dish surface, a significantly slowed growth rate, and (except for SK-MEL 3) increased pigmentation. The SK-MEL 5 line displays similar responses, but also shows increased dendritic morphology characteristic of differentiated melanocytes. The lines most sensitive to BQ788 (A375, SK-MEL 28, and RPMI 7951) have, in addition, cytoplasmic vacuoles and an almost complete loss of viability accompanied by a significant increase in TUNEL staining, which is suggestive of apoptosis.

These effects appear to be mediated specifically by the action of BQ788 on ETRB itself because the drug is ineffective on A375 cells in the presence of the ETRB agonist S6c. Further evidence for a specific effect of BQ788 on melanoma cells is its very different effect on kidney (293) cells. Moreover, the ETRA selective blocker BQ123 does not inhibit melanoma cell growth in culture, even at high concentration. Interestingly, the cell line with the highest degree of sensitivity to BQ788 treatment, RPMI 7951, has the lowest level of ETRB mRNA among the lines tested. Kikuchi et al. (13) found that human metastatic melanoma cells display decreased ETRB expression compared with primary melanoma cells, suggesting that metastatic melanoma cells could be the most sensitive to treatment with BQ788.

The findings on cell viability in culture, particularly with lines RPMI 7951, SK-MEL 28, and A375, as well as the TUNEL results in vitro and in vivo, argue that BQ788 can induce apoptosis. This is consistent with an autocrine/paracrine role for endothelins in melanoma survival and growth (12, 14). Further support comes from our observation that some of the melanoma lines express ET1 mRNA (data not shown). In addition, the ETRB-specific agonist stimulates growth of A375 cells (Fig. 5). The small but significant increase in the number of viable cells that can be seen with the selective ETRA antagonist BQ123 on A375 and SK-MEL 28 cells argues that the A and B receptors mediate an entirely different responses of endothelins on these cells. In the case of A375, Ohtani et al. (14) found that whereas ETRB may mediate proliferation, increased ETRA expression is associated with differentiation and growth arrest (14), and, as shown in our study, when ETRA is blocked, proliferation and/or survival can be enhanced. In this respect it is interesting that Zhang et al. (15) showed that the major ETRA transcript expressed by several melanoma cell lines is truncated and does not bind ET well.

Although it remains to be seen whether BQ788 is the most effective ETRB antagonist for stopping melanoma growth in vivo, there is evidence that such drugs can be well tolerated. In an animal model of hypertension, BQ788 reduced renal blood flow without affecting urine formation or causing toxic side effects (21). In clinical trials, i.v. administration of 1,000 mg of a nonselective ETR antagonist to healthy volunteers decreased peripheral vascular resistance and blood pressure (22), and another trial reported beneficial effects of another nonselective antagonist in patients with chronic heart failure (23).

Future experiments should address the question of why systemic treatment with BQ788 results in slower tumor growth for some animals while causing tumor regression in others. It also will be important to test whether the effects are reversible and whether ETRB antagonists also affect metastasis. Because ETRA antagonists can reduce the growth of ovarian carcinoma cells (24) and antagonize ET1-mediated proliferation of prostate cancer cells (25) in culture, it will be worth testing ET antagonists for treatment of these tumors as well.

Acknowledgments

We thank D. McDowell for help with laboratory administration, J. Baer for help and advice with animal care, and D. Anderson for providing comments on the manuscript. R.L. is supported by a Human Frontier Science Program Long Term Fellowship, and G.H. was supported by a Caltech Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ETRB and ETRA

endothelin receptors B and A

- S6c

sarafotoxin 6c

- HCO60

polyoxythylene (60) hydrogenated castor oil

- TUNEL

terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated UTP end labeling

References

- 1.Lecoin L, Lahav R, Martin F H, Teillet M A, Le Douarin N M. Develop Dyn. 1995;203:106–118. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002030111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lahav R, Lecoin L, Ziller C, Nataf V, Carnahan J F, Martin F H, Le Douarin N M. Differentiation. 1994;58:133–139. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.1995.5820133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang S, Luca M, Gutman M, McConkey D J, Langley K E, Lyman S D, Bar-Eli M. Oncogene. 1996;13:2339–2347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lecoin L, Lahav R, Dupin E, Le Douarin N. In: Molecular Basis of Epithelial Appendage Morphogenesis. Chuong C-M, editor. Georgetown, TX: R. G. Landes Company; 1998. pp. 131–154. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halaban R. Semin Oncol. 1996;23:673–681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Puffenberger E G, Hosoda K, Washington S S, Nakao K, deWit D, Yanagisawa M, Chakravart A. Cell. 1994;79:1257–1266. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hosoda K, Hammer R E, Richardson J A, Baynash A G, Cheung J C, Giaid A, Yanagisawa M. Cell. 1994;79:1267–1276. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baynash A G, Hosoda K, Giaid A, Richardson J A, Emoto N, Hammer R E, Yanagisawa M. Cell. 1994;79:1277–1285. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lahav R, Ziller C, Dupin E, Le Douarin N M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:3892–3897. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.3892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reid K, Turnley A M, Maxwell G D, Kurihara Y, Kurihara H, Bartlett P F, Murphy M. Development. 1996;122:3911–3919. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.12.3911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lahav R, Dupin E, Lecoin L, Glavieux C, Champeval D, Ziller C, Le Douarin N M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:14214–14219. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yohn J J, Smith C, Stevens T, Hoffman T A, Morelli J G, Hurt D L, Yanagisawa M, Kane M A, Zamora M R. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;201:449–457. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kikuchi K, Nakagawa H, Kadono T, Etoh T, Byers H R, Mihm M C, Tamaki K. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;219:734–739. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ohtani T, Ninomiya H, Okazawa M, Imamura S, Masaki T. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;234:526–530. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Y F, Jeffery S, Burchill S A, Berry P A, Kaski J C, Carter N D. Brit J Cancer. 1998;78:1141–1146. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okazawa M, Shiraki T, Ninomiya H, Kobayashi S, Masaki T. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:12584–12592. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.20.12584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ishikawa K, Ihara M, Noguchi K, Mase T, Mino N, Saeki T, Fukuroda T, Fukami T, Ozaki S, Nagase T, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:4892–4896. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.4892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamroun D, Mathieu M N, Clain E, Germani E, Laliberté M F, Laliberté F, Chevillard C. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1995;26, Suppl. 3:S156–S158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Itoh S, Sasaki T, Ide K, Ishikawa K, Nishikibe M, Yano M. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;195:969–975. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.2139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takasaki C, Tamiya N, Bdolah A, Wollberg Z, Kochva E. Toxicon. 1988;26:543–548. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(88)90234-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hashimoto N, Kuro T, Fujita K, Azuma S, Matsumura Y. Biol Pharmaceut Bull. 1998;21:800–804. doi: 10.1248/bpb.21.800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haynes W G, Ferro C J, O’Kane K P, Somerville D, Lomax C C, Webb D J. Circulation. 1996;93:1860–1870. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.10.1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sütsch G, Kiowski W, Yan X W, Hunziker P, Christen S, Strobel W, Kim J H, Rickenbacher P, Bertel O. Circulation. 1998;98:2262–2268. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.21.2262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bagnato A, Salani D, Di Castro V, Wu-Wong J R, Tecce R, Nicotra M R, Venuti A, Natali P G. Cancer Res. 1999;59:720–727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nelson J B, Chan-Tack K, Hedican S P, Magnuson S R, Opgenorth T J, Bova G S, Simons J W. Cancer Res. 1996;56:663–668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]