Abstract

Background

There is growing evidence that better outcomes are achieved when anticoagulation is managed by anticoagulation clinics rather than by family physicians. We carried out a randomized controlled trial to evaluate these 2 models of anticoagulant care.

Methods

We randomly allocated patients who were expected to require warfarin sodium for 3 months either to anticoagulation clinics located in 3 Canadian tertiary hospitals or to their family physician practices. We evaluated the quality of oral anticoagulant management by comparing the proportion of time that the international normalized ratio (INR) of patients receiving warfarin sodium was within the target therapeutic range ± 0.2 INR units (expanded therapeutic range) while they were managed in anticoagulation clinics as opposed to family physicians' care over 3 months. We measured the rates of thromboembolic and major hemorrhagic events and patient satisfaction in the 2 groups.

Results

Of the 221 patients enrolled, 112 were randomly assigned to anticoagulation clinics and 109 to family physicians. The INR values of patients who were managed by anticoagulation clinics were within the expanded therapeutic range 82% of the time versus 76% of the time for those managed by family physicians (p = 0.034). High-risk INR values (defined as being < 1.5 or > 5.0) were more commonly observed in patients managed by family physicians (40%) than in patients managed by anticoagulation clinics (30%, p = 0.005). More INR measurements were performed by family physicians than by anticoagulation clinics (13 v. 11, p = 0.001). Major bleeding events (2 [2%] v. 1 [1%]), thromboembolic events (1 [1%] v. 2 [2%]) and deaths (5 [4%] v. 6 [6%]) occurred at a similar frequency in the anticoagulation clinic and family physician groups respectively. Of the 170 (77%) patients who completed the patient satisfaction questionnaire, more were satisfied when their anticoagulant management was managed through anticoagulation clinics than by their family physicians (p = 0.001).

Interpretation

Anticoagulation clinics provided better oral anticoagulant management than family physicians, but the differences were relatively modest.

The oral anticoagulant warfarin sodium is one of the most commonly prescribed medications as a result of its effectiveness in preventing and treating arterial and venous thrombosis.1,2,3,4,5,6 Successful anticoagulant management requires careful monitoring of the international normalized ratio (INR), ongoing patient education, and good communication between patients and their caregivers.

Evidence is accumulating that the quality of oral anticoagulant therapy influences the risk of patients having undesirable outcomes. Subgroup analyses of studies have demonstrated that failure to reach the target INR increases the risk of thromboembolic complications, and prolongation of the INR beyond the target range clearly predisposes patients to the risk of major bleeding complications including intracerebral hemorrhage.7,8,9,10,11,12 To prevent undertreatment or overdosing of warfarin sodium, regular laboratory control of the INR and dose adjustments are necessary.

There are 3 primary models available for managing oral anticoagulant care: usual medical care by a patient's family physician, pharmacist-managed or physician-managed oral anticoagulation clinics and patient self-management.13 As a consequence of the complexity and the time requirements for managing oral anticoagulant therapy, anticoagulation clinics have been set up in Canada and the United States to provide comprehensive and systematic patient care and to ease the burden on the primary physician.

Anticoagulation clinics are designed to coordinate and optimize the delivery of anticoagulant therapy by determining the appropriateness of therapy, managing warfarin sodium dosing, and providing continuous monitoring of patients' INR results, dietary factors, concomitant medications and interfering disease states.14 Comprehensive education and good communication links are used in these clinics to maximize compliance and to optimize warfarin sodium management.

Existing evidence suggests that management of warfarin sodium by anticoagulation clinics is more likely to attain the desired patient outcomes and reduce costs per person-year of follow-up than routine medical care by family physicians.13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38 However, the available literature on the benefits of anticoagulation clinics consists mostly of descriptive reports, case–control studies or nonrandomized prospective studies.13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38 We conducted a randomized controlled trial to determine whether anticoagulation clinics improve the quality of anticoagulant management compared with family physician–based monitoring.

Methods

An open randomized controlled multicentre trial was conducted at the Queen Elizabeth II Health Sciences Centre, Halifax, NS, the Ottawa Hospital, Ottawa, Ont., and the London Health Sciences Centre, London, Ont., from January 1998 to September 2000 to compare the quality of oral anticoagulant monitoring in anticoagulation clinics and in family physician practice. The research protocol was approved by each hospital's ethics review board.

Randomization was stratified based on whether patients were previous or new users of warfarin sodium, whether the target INR was low intensity (INR 2.0–3.0) or high intensity (INR 2.5–3.5) and by study centre.1,2,3,4,5,6 New users were defined as those who had been prescribed warfarin sodium for less than 1 month. Patients who were expected to require warfarin sodium for a minimum of 3 months were eligible for this study. Patients were excluded if they met one of the following criteria: life expectancy of less than 3 months; major hemorrhagic contraindication to anticoagulation; refusal of the patient's family physician to participate; absence of a family physician; geographic inaccessibility for follow-up; and likelihood of poor compliance (e.g., patients who were unable to care for themselves, lacked adequate home support or were unwilling to comply with the treatment care plan).

All patients were initially evaluated by a hematologist and a clinical pharmacist in an anticoagulation clinic. All study patients received a standardized educational package that detailed the indication for therapy, the importance of complying with the regimen, the need for close monitoring, the potential risks of taking other medications, dietary considerations and the importance of self-monitoring for evidence of bleeding or thromboembolic complications. Informed consent was obtained from all participants and their family physicians. Once patients were on a stable warfarin sodium dose in an anticoagulation clinic (usually within 7 days), they were randomly allocated to either continuing to be managed at the anticoagulation clinic or having their family physician be responsible for anticoagulant monitoring over the next 3 months. The randomization codes were generated using a computerized random allocation sequence and were not revealed to the clinical pharmacist until completion of the initial education session and of the period during which each patient's warfarin sodium dosage was stabilized. Family physicians were informed by telephone of the outcome of randomization. If patients were randomly allocated to family physician monitoring, the physician was provided with the patients' warfarin sodium log, INR results, the date and location of the next INR test, and follow-up details of the study. These patients were given a reusable blood work requisition that included instructions for the laboratory to send INR reports by fax to the family physician managing the anticoagulant therapy and to mail INR reports to the anticoagulation clinic participating in this study. Patients were also given a logbook in which to record their INR results.

All patients were followed over a 3-month period. Investigators were blinded to the INR results of patients randomly allocated to family physician management. However, patients in the family physician arm were contacted by the study site coordinator at monthly intervals to confirm the frequency and location of INR tests, to determine whether they had any thromboembolic or major bleeding complications, and to identify any interruptions in warfarin sodium therapy due to surgery or dental procedures. For any missing INR reports, family physicians and laboratories were contacted for a hard copy of this information. At the end of the 3-month follow-up period, patients completed a questionnaire to determine their level of satisfaction with the care provided.

The primary study outcome was the proportion of time that patients receiving warfarin sodium had their INR within ± 0.2 units of the target therapeutic range (expanded therapeutic range) over a 3-month period while managed in an anticoagulation clinic compared with family physician care. For patients requiring warfarin sodium for the prevention or treatment of thrombosis (standard risk), the recommended range was 2.0–3.0.1,2,3,5,6 For patients who required warfarin sodium for the prevention of cardioembolic complications caused by prosthetic valves or recurrent thrombosis (high risk), the recommended range was 2.5–3.5.4 Because minor fluctuations defined by ± 0.2 units would be considered clinically unimportant and would not necessarily require a warfarin sodium dose adjustment, the defined expanded therapeutic ranges for this study were 1.8–3.2 for standard-risk and 2.3–3.7 for high-risk patients.

Anticoagulation control was calculated as the percentage of patient time spent within the target range using the method described by Rosendaal and colleagues.39 For those patients who had their warfarin sodium therapy temporarily interrupted either in preparation for upcoming surgical or dental procedures or because of thrombotic or bleeding complications, the interval between when the warfarin sodium dose was first withheld until 5 days after warfarin sodium was resumed was censored from the analysis.

Secondary outcome measures included rates of thromboembolic and major hemorrhagic complications in the 2 groups over the 3-month study period as determined by a centralized adjudication committee blinded to the treatment allocation group. Thrombotic events that were considered outcome measures included acute myocardial infarction, stroke, peripheral arterial occlusion, deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism, as defined by previously described criteria.2,3,4,5,6 Major bleeding was considered to be those events that resulted in death or the need for acute medical or surgical intervention, also as defined by previously described criteria.40 Patient satisfaction was determined by a previously validated questionnaire completed at the end of the 3-month follow-up period. The questionnaire consisted of 10 items.

Based on noncontrolled studies, it was estimated that with routine medical care by a patient's family physician, INR levels would be within the target range about 50% of the time.41,42,43 It was expected that care through an anticoagulation clinic would result in at least a 10% absolute improvement in this level to 60% and that this improvement would be considered clinically important. We assumed that the standard deviations of the means in the 2 groups were equal to 0.25, and therefore we would require a sample size of 62 per group to have 80% power and a 2-tailed α error of 0.05 to observe this difference in effect. Furthermore, it was agreed that enrolment in the study would continue until each centre accrued at least 20 patients in the trial and until at least 124 patients had been randomly allocated to a study group.

The primary analysis compared the proportion of time that INR values were within the expanded therapeutic range for patients managed by anticoagulation clinics as opposed to those managed by family physicians using an unpaired Student's t-test. An intention-to-treat analysis was performed. A 2-tailed p value of less than 0.05 was regarded as a statistically significant difference between the 2 groups. Rates of thrombotic and major hemorrhagic complications were compared between the 2 groups using Fisher's exact test. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals using the binomial distribution were calculated around these rates. Descriptive statistics and the χ2 test were used to compare the results of the patient satisfaction questionnaire.

Results

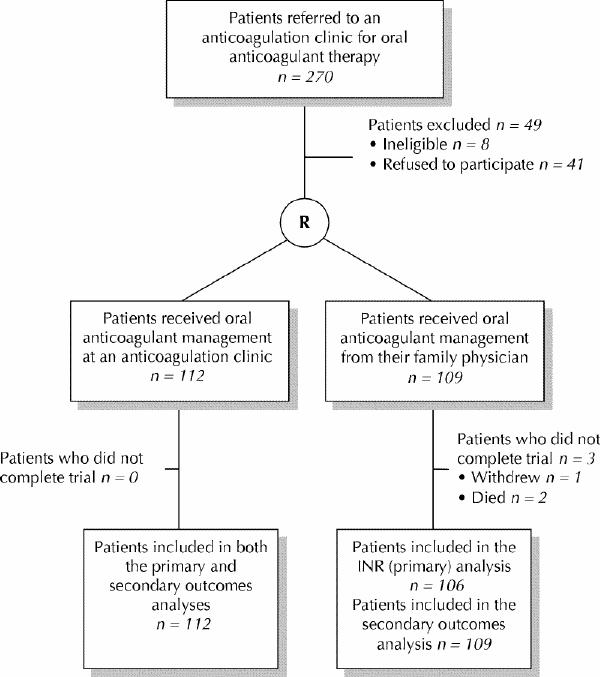

Two hundred and seventy patients who were referred to the 3 participating anticoagulation clinics were potentially eligible for the study, which was carried out between January 1998 and September 2000. Forty-one of these referred individuals and 6 individuals' family physicians refused to give informed consent to take part in the study, and 2 patients had no family doctor. Of the 41 patients who declined to participate, 20 were not interested in participating in a research study, and 12 were dissatisfied and 9 were satisfied with their family physicians' management of their oral anticoagulant therapy. Five of the family physicians who declined to participate in the study preferred to have their patients monitored in the anticoagulation clinics and the other family physician gave no reason for declining to participate in the study. The remaining 221 patients were enrolled in the study. One hundred and twelve patients were randomly allocated to an anticoagulation clinic and 109 patients were randomly allocated to their family physician for anticoagulant management (Fig. 1). Information about the warfarin dosage protocols used in the anticoagulation clinics is provided online in Appendices 1 and 2 at www.cmaj.ca.

Fig. 1: Flow of subjects through the study. R = randomization, INR = international normalized ratio.

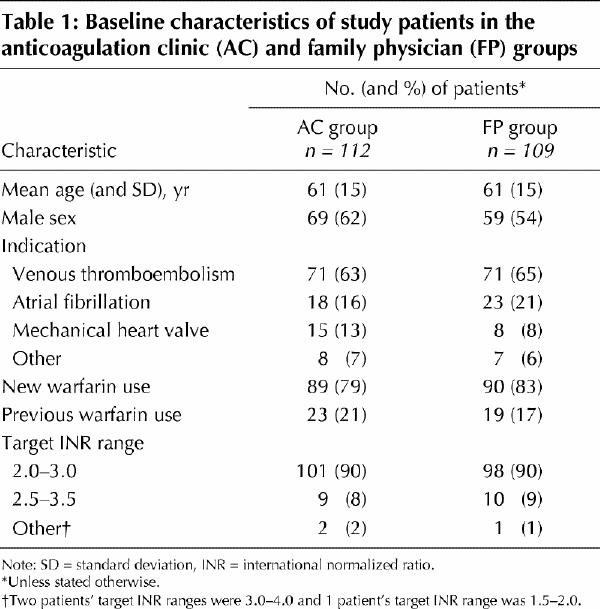

Patients' characteristics were similar with respect to age, sex, indication for anticoagulant therapy, new or previous warfarin use, and target INR range (Table 1). The primary indication for anticoagulation was venous thromboembolism in 142 (64%) patients. One hundred and seventy-nine (81%) patients were new users of warfarin sodium. The mean time taken to stabilize patients' dosage of warfarin sodium before randomization was 5.9 (standard deviation [SD] 4.7) days for the anticoagulation clinic group and 5.7 (SD 5.6) days for the family physician group.

Table 1

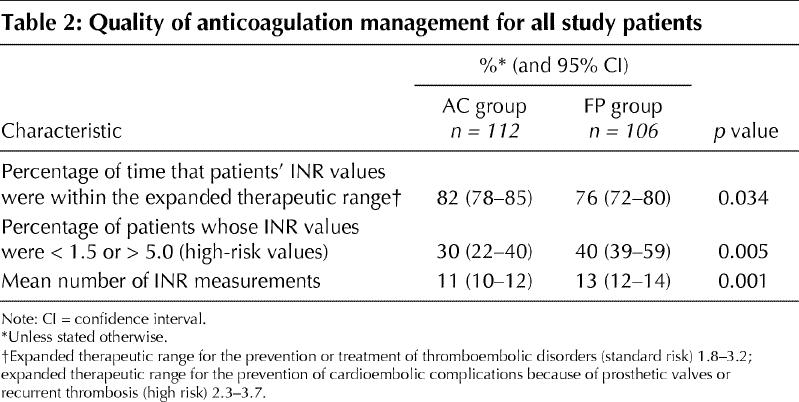

All patients in the anticoagulation clinic group and 106 patients in the family physician group completed the 3-month study. Two patients in the family physician group died within 1 week of randomization and 1 patient stopped taking warfarin sodium within 1 week of randomization due to noncompliance. These 3 patients were not included in the INR analysis, because only 1 INR measurement had been performed. An intention-to-treat analysis included the remaining patients. The INR of patients managed by anticoagulation clinics was within the expanded therapeutic range 82% (95% confidence interval [CI] 78%–85%) of the time versus 76% (95% CI 72%–80%) of the time for patients in the family physician group (p = 0.034) (Table 2). The INR of patients managed by anticoagulation clinics was within the actual therapeutic range 63% (95% CI 59%–67%) of the time versus 59% (95% CI 54%–64%) of the time for patients managed by family physicians (p = 0.19). Thirty percent (95% CI 22%–40%) of patients had high-risk INR values (defined as being < 1.5 or > 5.0) in the anticoagulation clinic group compared with 40% (95% CI 39%–59%) of patients in the family physician group (p = 0.005). The mean number of INR measurements performed in the anticoagulation clinics was 11 (95% CI 10–12) versus 13 (95% CI 12–14) for the family physician group over the 3-month period (p = 0.001).

Table 2

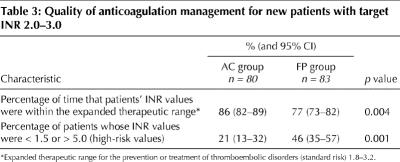

One hundred and sixty-three (74%) patients whose target INR was 2.0–3.0 received warfarin sodium therapy for the first time. Eighty patients were in the anticoagulation clinic group and 83 were in the family physician group. These patients' INR was within the expanded therapeutic range 86% (95% CI 82%–89%) of the time for anticoagulation clinics versus 77% (95% CI 73%–82%) of the time for family physicians (p = 0.004). Twenty-one percent (95% CI 13%–32%) of patients had high-risk INR values (< 1.5 or > 5.0) in the anticoagulation clinic group compared with 46% (95% CI 35%–57%) of patients in the family physician group (p = 0.001) (Table 3).

Table 3

Major bleeding events (2 [2%] v. 1 [1%]), thromboembolic events (1 [1%] v. 2 [2%]) and deaths (5 [4%] v. 6 [6%]) occurred at a similar frequency in the anticoagulation clinic and family physician groups respectively. In the anticoagulation clinic group, 1 patient had a stroke. In the family physician group, 2 patients developed deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Of the 5 deaths in the anticoagulation clinic group, 4 were from cancer and 1 from a stroke. Two patients in the family physician group died within the first week of the study. One patient who was receiving warfarin sodium for atrial fibrillation had an acute myocardial infarction 15 days after randomization. Ten days before the patient's death, the patient's INR was 1.9. The second patient was receiving oral anticoagulant therapy for deep vein thrombosis and died of cancer 15 days after randomization. Of the remaining 4 patients, 2 died of cancer, 1 from a pulmonary embolism and 1 from sepsis.

Of the 170 (77%) patients who completed the patient satisfaction questionnaire, 85% (95/112) were in the anticoagulation clinic group and 69% (75/109) were in the family physician group (p = 0.001). Ninety-six percent of patients in the anticoagulation clinic group reported that they were either very satisfied or satisfied with their overall warfarin care compared with 84% of patients in the family physician group (p = 0.001). The remaining 4% in the anticoagulation clinic group had no opinion and the remaining 16% in the family physician group were either dissatisfied or had no opinion. Patients in the anticoagulation clinic group reported that they were more satisfied with teaching (93% v. 80%), helpfulness of staff (98% v. 89%), availability of staff in an emergency (76% v. 67%) and time spent with staff (93% v. 76%) compared with the family physician group (p = 0.001).

Interpretation

The results of our study show that both models of care provided very high-quality oral anticoagulant management. The expanded therapeutic INR range of our study (within ± 0.2 units of the target therapeutic range) was achieved over 75% of the time in both patient groups. Oral anticoagulant management in anticoagulation clinics did achieve statistically significant improvements in the proportion of time patients' INR values were within the expanded therapeutic range, although the observed difference (6%) was less than the minimal clinically important difference (10%) from which the target sample size had been derived. Management by anticoagulation clinics also resulted in significantly fewer patients having high-risk INR values of less than 1.5 or greater than 5.0. The mean number of INR measurements performed was statistically significantly lower in the anticoagulation clinic arm of this study. Satisfaction with the quality of care was also statistically significantly higher among patients managed through anticoagulation clinics than with routine care.

Our study was not powered to detect differences in thromboembolic or bleeding outcomes between the 2 groups, and no trend favoured 1 modality over the other. The care provided in both arms of this study would be regarded as high quality compared with that reported in noncontrolled or registry studies.8,24,27,29,37,38 However, in the family physician arm of this study, the quality of INR monitoring was higher than previously reported in clinical trials.31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44 There are a few features of our study that may have accounted for the high-quality oral anticoagulant care in the family physician arm. First, all patients were seen initially in a specialized anticoagulation clinic and received detailed education regarding the use of and the risks and benefits of oral anticoagulant management. Second, patients had their dose of warfarin sodium stabilized before transfer of care. Third, there was good transitional care between our clinics and the family physicians who provided routine anticoagulant care. The patients' family physicians were notified of the indication for oral anticoagulant management, the INR results and the warfarin sodium dosage during the stabilization period of the study. Fourth, family physicians were aware that they were participating in a clinical trial and may have been more vigilant about monitoring anticoagulant care than in routine practice. In addition, although only 6 family physicians refused to participate, it is possible that those who did refuse may have perceived their ability to regulate warfarin to be substandard, and their elimination from the pool of family physicians could have artificially increased the excellent level of monitoring.

There has been much debate about the most appropriate model for oral anticoagulant therapy care. Noncontrolled studies have suggested that specialized anticoagulation clinics with highly trained pharmacists, nurses and/or physicians provide better anticoagulant care than family physicians.29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38 Such studies suggest that the care rendered by anticoagulation clinics results in improved anticoagulant management (more INR results and time in the target range) with fewer major bleeding and thromboembolic complications.29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38

We believe that the results of our study should be generalizable to other tertiary care centres. The refusal rate on the part of either patients or the family physicians was low, making it unlikely that selection bias accounted for the results. The results were also similar when we considered patients who were receiving oral anticoagulant therapy for the first time.

There are several limitations to our study. First, the follow-up period was relatively short. It is possible that with time, differences in compliance or follow-up could differentially affect the quality of anticoagulant care in the 2 groups. Second, our study was underpowered to detect differences in clinical outcomes, which would be the ideal end point in comparing models of oral anticoagulant care. Finally, our study may not mimic routine medical care in many centres. Because all patients were initially seen in an anticoagulation clinic and received detailed educational packages, these study results may not necessarily be generalizable to routine care by family physicians if these educational and clinical measures are not undertaken.

In summary, anticoagulation clinics provided better oral anticoagulant management than family physicians did, but the differences were relatively modest. Further randomized controlled trials to evaluate a much larger cohort for a longer duration are required to determine whether anticoagulation clinics improve patient outcomes and are cost-effective.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jennifer Blundell-Ramsay, Queen Elizabeth II Health Sciences Centre, and Melinda Robbins, London Health Sciences Centre, for their assistance with data collection; Jimi Kaye, Queen Elizabeth II Health Sciences Centre, for his statistical support with the patient satisfaction questionnaires; Hilary Jarvis, Queen Elizabeth II Health Sciences Centre, for her assistance in developing the patient satisfaction questionnaire; Marlene Ross, Queen Elizabeth II Health Sciences Centre, for processing the data for the patient satisfaction questionnaire; and Joanne Burdock, Queen Elizabeth II Health Sciences Centre, for her expert secretarial assistance with this manuscript.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: All authors contributed significantly to the conception or design of the study, or acquisition of the data, or analysis and interpretation of the data; and drafted the article or revised it critically for important intellectual content; and gave final approval of the version to be published.

Financial support for this study was provided by institutional grants from the Queen Elizabeth II Health Sciences Centre Research Foundation, Halifax, NS; the Physicians' Services Incorporated Foundation, Ottawa, Ont.; and the London Health Sciences Centre Internal Research Fund, London, Ont.

Competing interests: None declared.

Correspondence to: Dr. S. Jo-Anne Wilson, Assistant Professor of Pharmacy, Queen Elizabeth II Health Sciences Centre, Pharmacy Department — Victoria General, Rm. 2043, 1278 Tower Rd., Halifax NS B3H 2Y9; fax 902 473-6812; JoAnne.Wilson@cdha.nsheatlh.ca

References

- 1.Geerts WH, Heit JA, Clagett GP, Pineo GF, Colwell CW, Anderson FA Jr, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism. Chest 2001;119(Suppl 1): 132S-75S. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Hyers TM, Angelli G, Hull RD, Morris TA, Samama M, Tapson V, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for venous thromboembolic disease. Chest 2001; 119 (Suppl 1):176S-93S. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Albers GW, Dalen JE, Laupacis A, Manning WJ, Petersen P, Singer DE, et al. Antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation. Chest 2001;19(Suppl 1):194S-206S. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Stein PD, Alpert JS, Bussy HI, Dalen JE, Turpie AGG. Antithrombotic therapy in patients with mechanical and biological prosthetic heart valves. Chest 2001;119(Suppl 1):220S-27S. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Cairns JA, Theroux P, Lewis HD, Ezekowitz M, Meade TW. Antithrombotic agents in coronary artery disease. Chest 2001;119(Suppl 1):228S-52S. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Albers GW, Amarenco P, Easton JD, Sacco RL, Teal P. Antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy for ischemic stroke. Chest 2001;119(Suppl):300S-20S. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Fihn FD, Callahan CM, Martin DC, McDonell MB, Henikoff JG, White RH. The risk for and severity of bleeding complications in elderly patients treated with warfarin. Ann Intern Med 1996;124:970-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Palareti G, Leali N, Coccheri S, Poggi M, Manotti C, D'Angelo A, et al. Bleeding complications of oral anticoagulant treatment: an inception-cohort, prospective collaborative study. (ISCOAT). Italian Study on Complications of Oral Anticoagulant Therapy. Lancet 1996;348:423-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Hylek EM, Singer DE. Risk factors for intracranial hemorrhage in outpatients taking warfarin. Ann Intern Med 1994;120:897-902. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Hart RG, Boop BS, Anderson DC. Oral anticoagulants and intracranial hemorrhage: facts and hypotheses. Stroke 1995;26:1471-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Atrial Fibrillation Investigators. Risk factors for stroke and efficacy of anti-thrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation: analysis of pooled data from five randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med 1994;154:1449-57. [PubMed]

- 12.Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation Investigators. Bleeding during antithrombotic therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation. Arch Intern Med 1996; 156: 409-16. [PubMed]

- 13.Ansell J, Hirsh J, Dalen J, Bussey H, Anderson D, Poller L, et al. Managing oral anticoagulant therapy. Chest 2001;119(Suppl):22S-38S. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Ansell J, Buttaro ML, Thomas OV, Knowlton CH, the Anticoagulation Guidelines Task Force. Consensus guidelines for coordinated outpatient oral anticoagulation therapy management. Ann Pharmacother 1997;31:604-15. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Landefeld CS, Goldman L. Major bleeding in outpatients treated with warfarin: incidence and prediction by factors known at the start of outpatient therapy. Am J Med 1989;87:144-51. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Glitter MJ, Jaeger TM, Petterson TM, Gersh BJ, Silverstein MD. Bleeding and thromboembolism during anticoagulant therapy: a population-based study in Rochester, Minnesota. Mayo Clin Proc 1995;70:725-33. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Beyth RJ, Quinn LM, Landefeld S. Prospective evaluation of an index for predicting the risk of major bleeding in outpatients treated with warfarin. Am J Med 1998;105:91-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Forfar JC. Prediction of haemorrhage during long-term oral coumadin anticoagulation by excessive prothrombin ratio. Am J Heart 1982;103:445-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Errichetti AM, Holden A, Ansell J. Management of oral anticoagulation therapy: experience with an anticoagulation clinic. Arch Intern Med 1984;144: 1966-8. [PubMed]

- 20.Conte RR, Kehoe WA, Nielson N, Lodhia H. Nine-year experience with a pharmacist-managed anticoagulation clinic. Am J Hosp Pharm 1986;43:2460-4. [PubMed]

- 21.Petty GW, Lennihan L, Mohr JP, Hauser WA, Weitz J, Owen J, et al. Complications of long-term anticoagulation. Ann Neurol 1988;23:570-4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Charney R, Leddomado E, Rose DN, Fuster V. Anticoagulation clinics and the monitoring of anticoagulant therapy. Int J Cardiol 1988;18:197-206. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Bussey HI, Rospond RM, Quandt CM, Clark GM. The safety and effectiveness of long-term warfarin therapy in an anticoagulation clinic. Pharmacotherapy 1989;9:214-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Seabrook GR, Karp D, Schmitt DD, Bandyk DF, Towne JB. An outpatient anticoagulation protocol managed by a vascular nurse-clinician. Am J Surg 1990; 160:501-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Fihn SD, McDonnell M, Martin D, Henikoff J, Vermes D, Kent D, et al. Risk factors for complications of chronic anticoagulation. A multicenter study. Warfarin Optimized Outpatient Follow-up Study Group. Ann Intern Med 1993;118:511-20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.van der Meer FJM, Rosendaal FR, Vandenbrouke JP, Briet E. Bleeding complications in oral anticoagulant therapy: an analysis of risk factors. Arch Intern Med 1993;153:1557-62. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Cannegeiter SC, Rosendaal FR, Wintzen AR, van der Meer FJM, Vandenbroucke JP, Briet E. Optimal oral anticoagulant therapy in patients with mechanical heart valves. N Engl J Med 1995;333:11-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Palareti G, Manotti C, D'Angelo A, Pengo V, Erba N, Moia M, et al. Thrombotic events during oral anticoagulant treatment: results of the inception-cohort, prospective, collaborative ISCOAT study. ISCOAT study group (Italian Study on Complications of Oral Anticoagulant Therapy). Thromb Haemost 1997;78:1438-43. [PubMed]

- 29.Garabedian-Ruffalo SM, Gray DR, Sax MJ, Ruffalo RL. Retrospective evaluation of a pharmacist-managed warfarin anticoagulation clinic. Am J Hosp Pharm 1985;42:304-8. [PubMed]

- 30.Cortelazzo S, Finazzi VP, Viero P, Galli M, Remuzzi A, Parenzan L, et al. Thrombotic and hemorrhagic complications in patients with mechanical heart valve prosthesis attending an anticoagulation clinic. Thromb Haemost 1993; 69:316-20. [PubMed]

- 31.Wilt VM, Gums JG, Ahmed OI, Moore LM. Outcome analysis of a pharmacist-managed anticoagulation service. Pharmacotherapy 1995;15:733-9. [PubMed]

- 32.Chiquette E, Amato MG, Bussey HI. Comparison of an anticoagulation clinic with usual medical care: anticoagulation control, patient outcomes, and health care costs. Arch Intern Med 1998;158:1641-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Chenalla FC, Klotz TA, Gill MA, Kern JW, McGhan WF, Paulson YJ, et al. Comparison of physician and pharmacist management of anticoagulant therapy of inpatients. Am J Hosp Pharm 1983:40(10):1642-5. [PubMed]

- 34.Pell JP, McIver B, Stuart P, Malone DN, Alcock J. Comparison of anticoagulant control among patients attending general practice and a hospital anticoagulant clinic. Br J Gen Pract 1993;43:152-4. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Chamberlain MA, Sageser NA, Ruiz D. Comparison of anticoagulation clinic patient outcomes with outcomes from traditional care in a family medicine clinic. J Am Board Fam Pract 2001;14:16-21. [PubMed]

- 36.Holden J, Holden K. Comparative effectiveness of general practitioner versus pharmacist dosing of patients requiring anticoagulation in the community. J Clin Pharm Ther 2000;25:49-54. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.White RH, McCurdy SA, Marensdorff HV, Woodruff DE, Leftgoff L. Home prothrombin time monitoring after the initiation of warfarin therapy: a randomized, prospective study. Ann Intern Med 1995;111:730-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Ansell JE, Patel N, Ostrovsky D, Nozzolillo E, Peterson AM, Fish L. Long-term patient self-management of oral anticoagulation. Arch Intern Med 1995; 155: 2185-9. [PubMed]

- 39.Rosendaal FR, Cannegieter SC, van der Meer FJM, Briet E. A method to determine the optimal intensity of oral anticoagulant therapy. Thromb Haemost 1993;39:236-9. [PubMed]

- 40.Anderson DR, Levine M, Gent M, Hirsh J. Validation of a new criteria for the evaluation of bleeding during antithrombotic therapy. Thromb Haemost 1993; 69:650.

- 41.Gottlieb LK, Salem-Schatz S. Anticoagulation in atrial fibrillation: Does efficacy in clinical trials translate into effectiveness in practice? Arch Intern Med 1994; 154:1945-53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Holm T, Lassen JF, Husted SE, Christensen P, Heickendorff L. Identification and surveillance of patient on oral anticoagulant therapy in a large geographic area-use of laboratory information systems. Thromb Haemost 1999; 82: (Suppl): 858-9.

- 43.Horstkotte D, Piper C, Wiemer M, Schulte HD, Schultheiss HF. Improvement of prognosis by home prothrombin estimation in patients with life-long anticoagulation therapy [abstract]. Eur Heart J 1996;17(Suppl):230.8732376

- 44.Sawicki PT. A structural teaching and self-management program for patient receiving oral anticoagulation: a randomised controlled trial. Working Group for the Study of Patient Self-Management of Oral Anticoagulation. JAMA 1999; 281 (2):145-50. [DOI] [PubMed]