Abstract

Background/Objectives:

Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs) have been published on a number of topics in spinal cord injury (SCI) medicine. Research in the general medical literature shows that the distribution of CPGs has a minimal effect on physician practice without targeted implementation strategies. The purpose of this study was to determine (a) whether dissemination of an SCI CPG improved the likelihood that patients would receive CPG recommended care and (b) whether adherence to CPG recommendations could be improved through a targeted implementation strategy. Specifically, this study addressed the “Neurogenic Bowel Management in Adults with Spinal Cord Injury” Clinical Practice Guideline published in March 1998 by the Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine

Methods:

CPG adherence was determined from medical record review at 6 Veterans Affairs SCI centers for 3 time periods: before guideline publication (T1), after guideline publication but before CPG implementation (T2), and after targeted CPG implementation (T3). Specific implementation strategies to enhance guideline adherence were chosen to address the barriers identified by SCI providers in focus groups before the intervention.

Results:

Overall adherence to recommendations related to neurogenic bowel did not change between T1 and T2 (P = not significant) but increased significantly between T2 and T3 (P < 0.001) for 3 of 6 guideline recommendations. For the other 3 guideline recommendations, adherence rates were noted to be high at T1.

Conclusions:

While publication of the CPG alone did not alter rates of provider adherence, the use of a targeted implementation plan resulted in increases in adherence rates with some (3 of 6) CPG recommendations for neurogenic bowel management.

Keywords: Spinal cord injuries, Neurogenic bowel, Practice guidelines, Consensus guidelines, Patient education

INTRODUCTION

Neurogenic bowel dysfunction is a major potential life-limiting problem after spinal cord injury (SCI). Fecal incontinence, difficulty with evacuation, and complications related to abnormal bowel function affect quality of life (1,2) and medical status for many individuals with SCI. In one study, patients reported loss of bowel and bladder function second only to loss of extremity function in its importance (1). Furthermore, bowel management is recognized as an area that persons with chronic SCI and their families find difficult to manage successfully (3,4). Fecal incontinence occurs with varying frequency in up to 75% of persons with SCI (5,6). Medical problems associated with neurogenic bowel may include poorly localized abdominal pain, difficulty or prolonged time with bowel evacuation, autonomic dysreflexia, hemorrhoids, rectal bleeding, bowel obstruction, and others (7). Furthermore, equipment used for bowel care may present safety hazards, including risk of falls (8,9). Consensus exists among experts in SCI medicine that appropriate bowel management is critical to minimize these problems.

Despite the clinical importance in this population, there is a paucity of research to compare efficacy of medications or management strategies for neurogenic bowel dysfunction. In recognition of these facts, the Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine, a group of specialists from diverse disciplines involved in the care of persons with SCI, published Clinical Practice Guidelines for Neurogenic Bowel Management in Adults with Spinal Cord Injury in March 1998 (10).

Effective use of clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) is thought to improve the process and outcomes of health care, decrease practice variation, and optimize resource use. However, there is evidence that simply distributing the CPGs results in little improvement in patient care and outcomes, because guideline adherence and application to practice may not occur (11–13). Instead, a large body of literature supports the need for targeted dissemination and implementation strategies to promote changes in clinician behavior (14,15). No single approach to improving adherence can be recommended on the basis of evidence in the literature. Complex interventions involving multiple strategies (eg, education, use of protocols, and improved methods for documenting care) may improve adherence and control for some patients. However, a plethora of evidence shows that educational interventions are unlikely to be effective by themselves (16). Factors that improve adherence include simplicity of the recommendation, its closeness to current practice, the need for few types of providers, and low complexity of the behavior being modified. Single strategy approaches have not been strongly related to improvement of clinician adherence to CPGs. The most effective strategies have involved multi-faceted approaches, including identification of specific barriers to guideline implementation, designation of staff members (clinical champions) to advocate for guideline adherence, and visits by outside experts to present authoritative arguments for behavior change (academic detailing).

The purposes of this study were twofold: (a) to determine whether simply distributing the guideline for “Neurogenic Bowel Management in Adults With Spinal Cord Injury” would increase the likelihood of veterans with SCI receiving CPG-recommended care, and (b) to determine whether a targeted implementation strategy would improve provider adherence. Our expectation was that distribution of the guidelines without a targeted implementation plan would result in minimal changes in provider practices, whereas a targeted intervention approach would result in a significant increase in provider adherence.

An expert panel was convened to translate the neurogenic bowel CPGs into specific performance criteria that could be assessed using existing data. The expert panel consisted of members of the original panel that developed the CPG for the Consortium as well as practicing Veteran Affairs SCI physicians and nurses and research methodologists. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality criteria for the selection of appropriate guidelines and identification of performance criteria were used during this process; as recommended, a subset of guidelines with the potential for greatest impact were selected (17,18). Other factors considered in selection of guidelines included the potential for morbidity and mortality, the expectation that compliance was suboptimal for the item, and the ability to determine compliance from a chart review process. Consensus on these factors was achieved, and a subset of the guidelines was chosen for implementation.

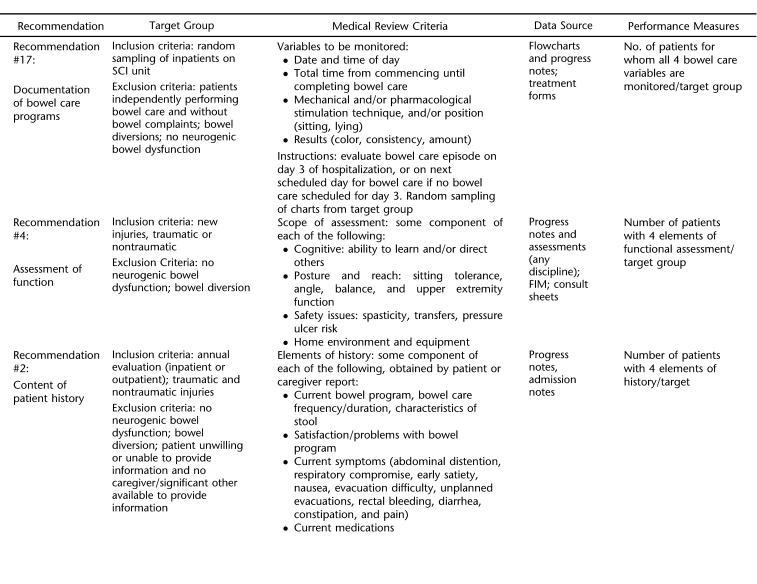

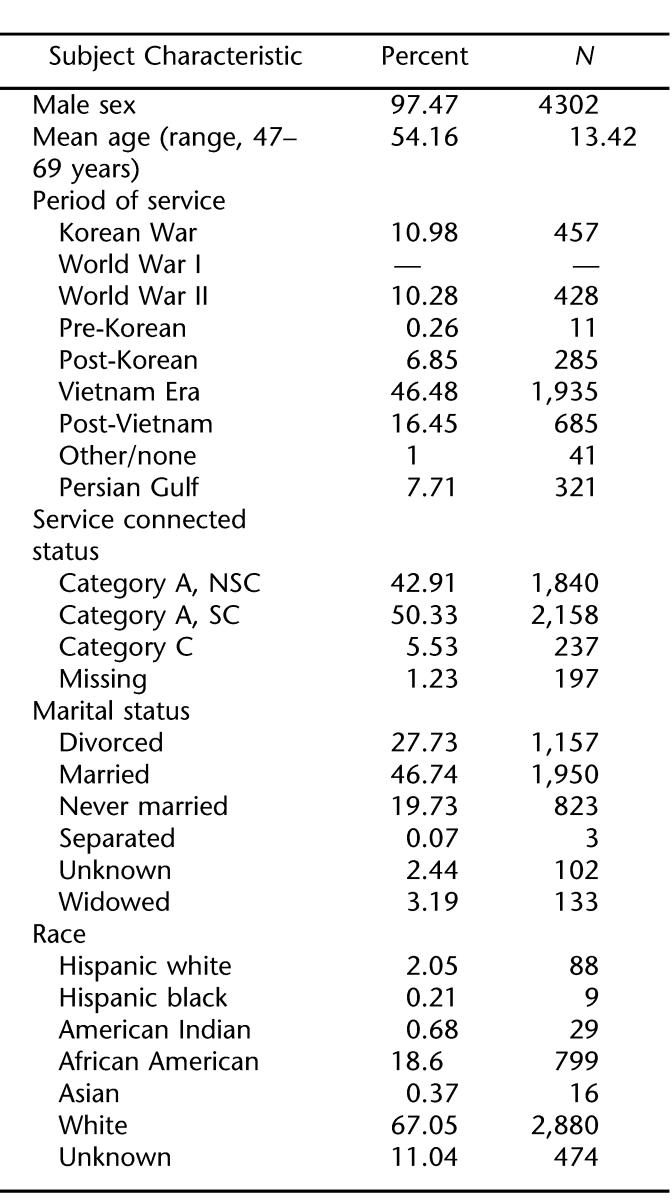

The specific guideline recommendations chosen and performance criteria developed for the study are summarized in Table 1. This table specifies the target population for each of the performance measures (eg, chronic patients, acute patients, or both). The specific inclusion and exclusion criteria varied with each performance measure and are outlined in Table 1. The specific review criteria and the performance criteria are listed by recommendation, along with a subset of exceptions for which deviation from guideline-recommended care would be permissible. To the degree that it was feasible, the expert panel followed the exact wording of the guideline recommendation when developing exclusionary criteria for each recommendation. The CPGs failed to address how frequently certain factors would have to be documented to calculate adherence. Consequently, the expert panel used their expertise to suggest reasonable time periods during which it would be expected that certain assessments should have been conducted.

Table 1.

Performance Measures for Neurogenic Bowel Management

To be eligible to be included in the performance measures, the patient had to have an episode of care with a neurogenic bowel diagnosis (ICD-9 CM 564.81). Additional targeting criteria addressed the precise target SCI population (acute or chronic SCI) and care setting (inpatient vs outpatient, not institutional long-term care) where the CPG recommended care would have been provided. Exclusionary criteria included patient refusal, patient cognitive deficits, lack of caregiver, and/or presence of a bowel diversion.

METHODS

Study Design

The study involved both retrospective and prospective review of medical records for persons with SCI served at 6 Veteran Affairs SCI Centers. Data were abstracted from medical charts for 3 time periods: before guideline publication (T1: November 1, 1996 to January 31, 1998), after guideline publication but before targeted dissemination and implementation (T2: July 1, 1998 to September 30, 1999), and after dissemination and implementation strategies (T3: July 15, 2000 to July 15, 2001). A parallel study involving the CPG for Prevention of Thromboembolism in SCI was conducted concurrently with this study (19).

Setting and Patients

The VA operates 23 SCI Services based at medical centers throughout the United States. Six VA SCI Services were chosen to represent a range of SCI Centers in terms of number of beds, geographic location, affiliation with university medical centers, and urban/rural settings. The 6 units had a range of 30 to 70 inpatient beds (mean = 44) and in fiscal year 2003 served a population of 3,246 veterans with acute and chronic SCI, providing primary and specialty care. The number of eligible patients with SCI ranged from 244 to 853 per site. In general, individuals receiving acute rehabilitation at the study centers represent a lower number of patients with acute SCI per year than is typical for a model SCI system.

Sample Characteristics

The sample population included all of the patients with acute injuries and all patients who had an annual evaluation during the time period of the study, in each of the participating centers. Each patient's record was reviewed for eligibility for each recommendation. Each record had the potential for being reviewed multiple times to assess eligibility for each of the guideline recommendations. Thus, patient records could potentially have been evaluated for multiple recommendations over multiple time periods, including eligibility over the 3 time periods. The actual sample for each recommendation is described below.

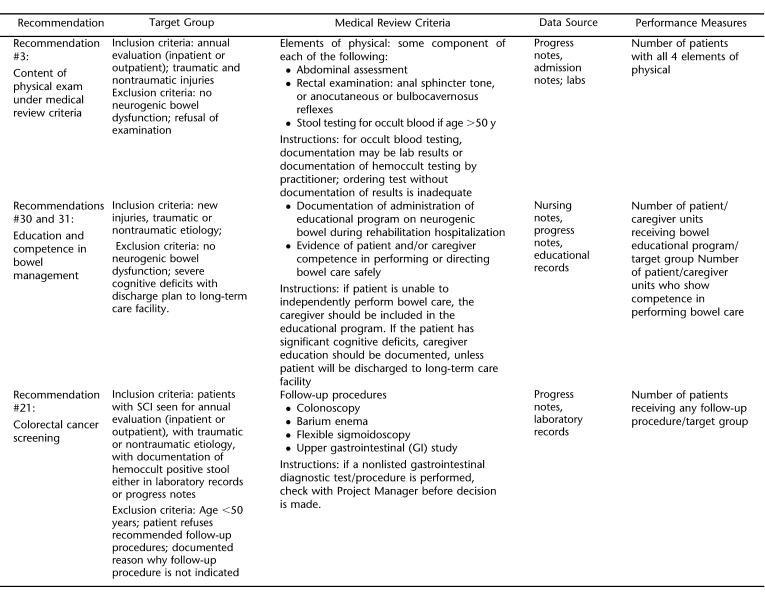

As shown in Table 2, across the 3 time periods, a total of 9,851 observations (and 3,831 admissions) were evaluated to assess adherence for Recommendations 2 and 3 (Content of Patient History and Physical Exam). Because of the detailed information required to meet the adherence criteria, it was expected that these assessments would be conducted either during the veteran's annual evaluation or during inpatient medical admissions and not at routine outpatient clinic visits. These 2 recommendations applied to all veterans with acute or chronic injuries.

Table 2.

Sample Size

Across the 3 time periods, a total of 2,719 observations of individuals with acute SCI were evaluated to assess adherence for Recommendation 4, Assessment of Function; Recommendation 30, Bowel Management Education; and Recommendation 31, Bowel Management Competence. It was expected that these assessments would be conducted during the initial inpatient rehabilitation after SCI.

Across the 3 time periods, a total of 627 observations (and 217 admissions) were evaluated to assess adherence for Recommendation 17, Documentation of Bowel Program. These assessments were to be conducted during inpatient medical admissions (including those for annual evaluations) but not during routine outpatient clinic visits. Charts were reviewed on admission day 3 of hospitalization or on the next scheduled bowel care day. This recommendation was determined to apply to all veterans with acute or chronic injuries.

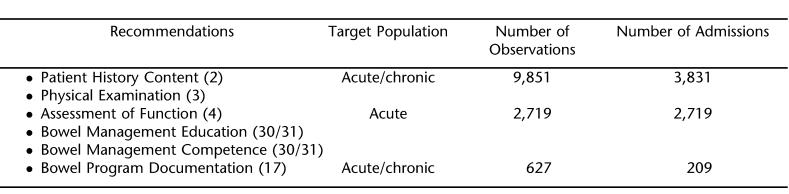

Patient Characteristics

Table 3 displays descriptive characteristics of the individuals included in the adherence sample. The overwhelming majority of individuals were men (97.5%), with a mean age of 54 years (range, 47–69 years). Most veterans served during the Vietnam era (46%), with about 11% from the World War II and Korean eras. About one half of the sample was service-connected, indicating that their injuries were incurred as part of their military service. Just under one half of the sample were married, with a slight majority of unmarried (never married, divorced, or widowed). Two thirds of the sample were white, and about one fifth (18.8%) were African American.

Table 3.

Sample Characteristics (n = 4432)

Human Subjects Review

The study received approval from relevant institutional boards at each Veteran Affairs Medical Center and/or from its associated university institutional review boards, as applicable. The institutional review boards at the participating sites agreed that the study posed only a “minimal risk” as specified in Title 45 CFR 46.116 and, as a result, the requirement of signed informed consent was waived.

Data Collection Protocol

Registered nurses with experience in SCI nursing who were familiar with the medical records used at the sites abstracted study data from patient medical records. A training manual was developed to enable data abstractors to assess specific performance criteria for each guideline recommendation. Before beginning data collection, a 3-day meeting was held in Tampa, Florida to train all abstractors. Once data collection commenced, monthly conference calls were held to clarify and resolve issues encountered at each site. Intra- and interrater reliability was established after training/before data collection and was reevaluated annually throughout data collection. The initial value of j obtained ranged from 0.35 (fair amount of agreement) to 1.00 (perfect agreement) as defined by Landis and Koch (20). Feedback and discussion successfully improved the performance of abstractors; a minimum level of interrater reliability at 0.85 was maintained throughout the study.

Interventions

Focus groups were conducted at each of the 6 sites to identify potential facilitators and barriers to implementation of the Neurogenic Bowel CPG. A description of the focus group procedure and an analysis of the types of facilitators and barriers identified can be found elsewhere (21). Briefly, health care professionals (including physicians, physician assistants, nurses, and therapists) at each participating site identified site-specific barriers to CPG implementation. After analyzing content from the focus groups, two targeted intervention strategies were chosen to address provider-perceived barriers to implementing recommendations of the guideline. These were (a) development and dissemination of a standardized documentation template and (b) development of a patient-mediated intervention, based on the importance of the patient in managing neurogenic bowel.

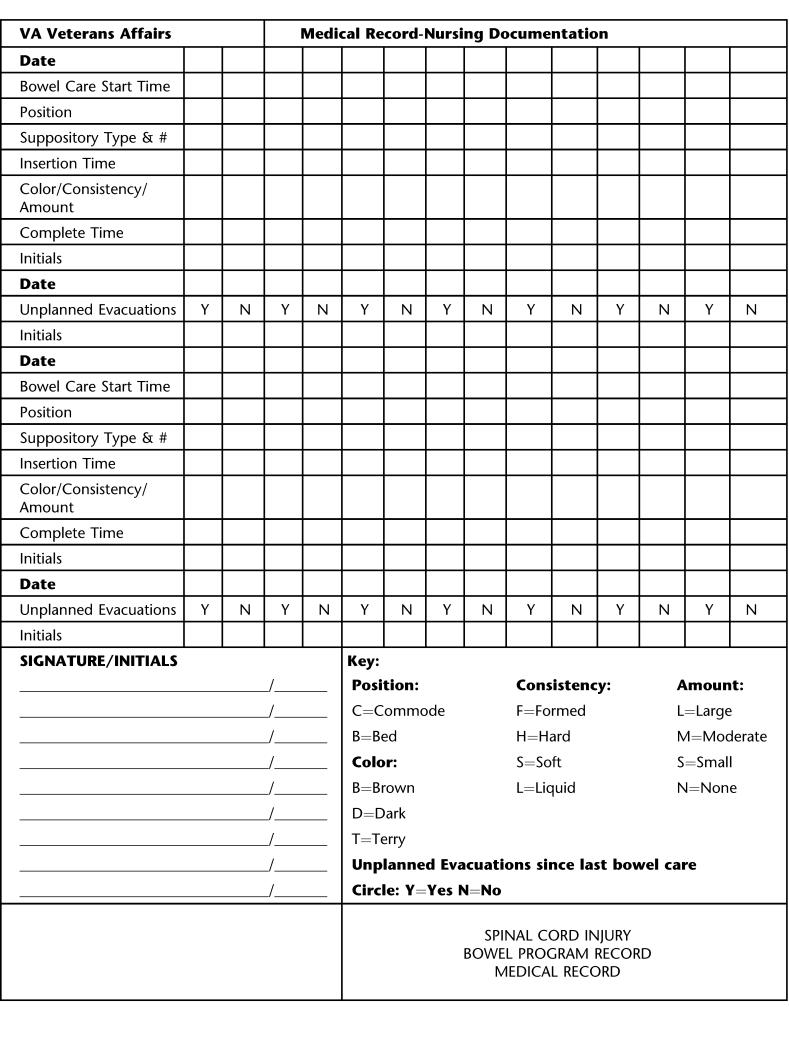

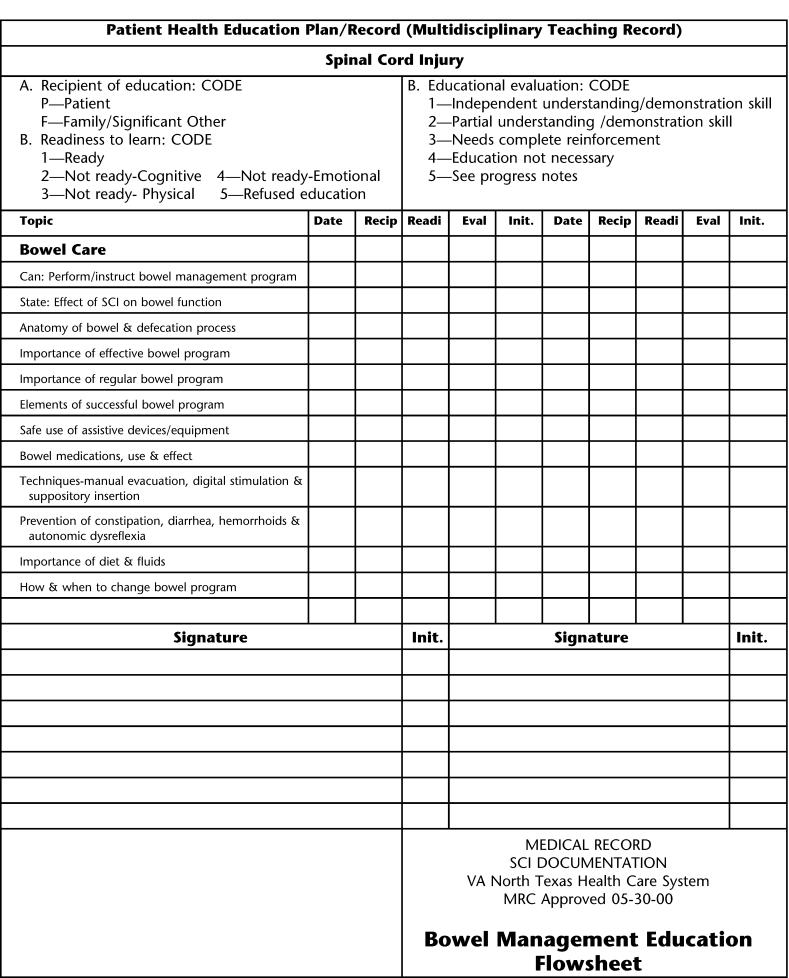

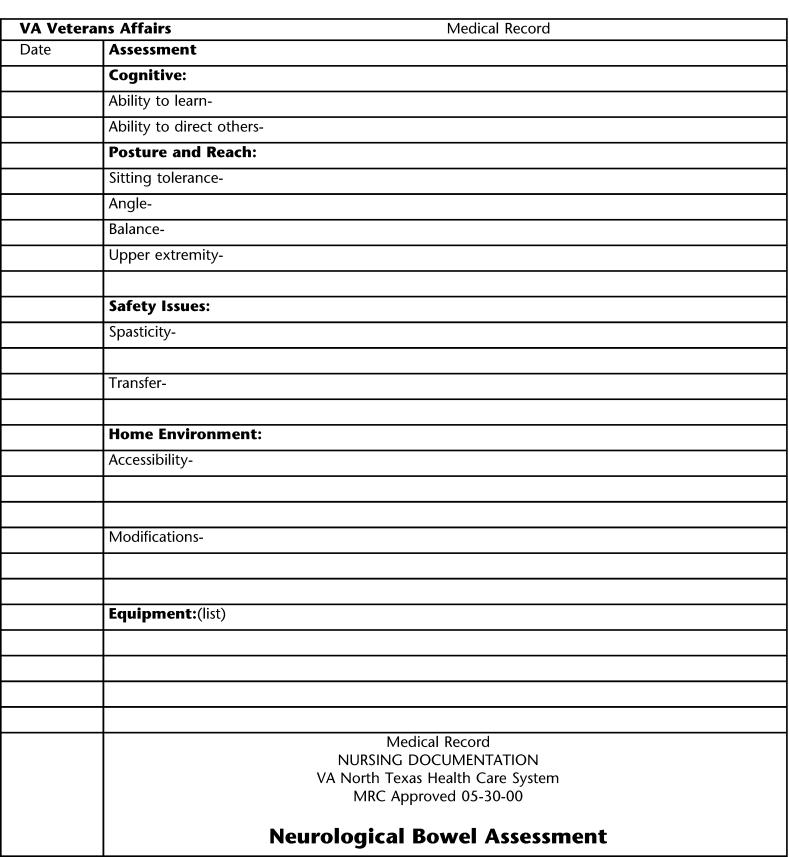

Focus groups participants identified as major obstacles to implementation the inability to easily document staff activities in the area of bowel care performance and education of patient and family caregivers. In fact, one site discovered that the lack of documentation of a number of aspects of bowel care was caused by staff discarding the nursing flow sheets used to track bowel care once the care was provided. During the implementation phase of the study, new documentation forms for bowel care programs were developed and approved by each Veteran Affairs Medical Center Forms Committee. Electronic and paper versions were developed, based on the type of medical record in use at each site at the time of the study. The templates were distributed to the inpatient units at the 6 participating sites for use in directing and documenting various aspects of neurogenic bowel care. A sample bowel care documentation form is shown (Form 1). Bowel management education flow sheets (Form 2) and forms for assessment of patient or caregiver competence (Form 3) were used at each for the sites to facilitate these processes. Variability in the design of these forms was allowed between sites, provided that all critical elements were included.

Form 1. Bowel Care Documentation Form.

Form 2. Bowel Management Education Flow Sheet.

Form 3. Assessment of Patient or Caregiver Competence.

Data Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Separate analyses were conducted for acute and chronic observations. Guideline adherence rates were calculated for each recommendation and time period. Stratified statistical analyses of the relationship between adherence, time period, and hospital were conducted using the Mantel-Haenszel statistic (22). Multiple comparisons and tests were conducted to examine variability within and between hospitals, as recommended by Zeger et al (23). In addition, a Poisson regression model was used to examine dependent variables with low occurrence frequency (eg, the number of interventions received during a specific admission) (24). These rates were examined to determine whether adherence rates varied across time, hospitals, and patients.

RESULTS

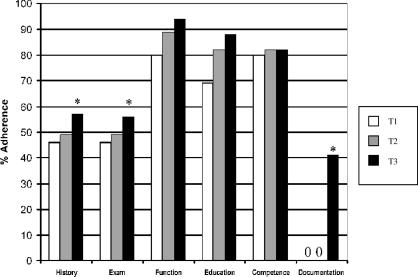

Overall adherence rates for the guidelines studied are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Overall adherence rates.

Recommendation #2 and #3: Patient History/Physical Examination

Medical record data indicated that a full neurogenic bowel history (defined as description of bowel program, satisfaction, and symptoms) and the content of the physical examination (abdominal, rectal and anal tone examination, and stool testing) at the time of the veteran's annual evaluation was taken from about one half of those who were eligible at T1 (before CPG publication). Rates of adherence increased slightly at T2, but this change between them was not statistically significant. A significant increase (P < 0.001) in adherence was observed between T2 (postpublication/preimplementation) and T3 (postimplementation). Rates of adherence for patient history recommendation increased (or stayed at 100%) at 5 of the 6 sites by T3. Rates of adherence for physical examination recommendation increased (or stayed at 100%) at 4 of the sites, while decreasing at 2 sites by T3.

Recommendation #4: Assessment of Function

Rates of adherence increased at all 3 time periods, but these were not statistically significant. Adherence rates increased or stayed about the same at all 6 sites.

Recommendation #17: Documentation of Bowel Care Programs

Inclusion of all 4 variables, (a) date/time, (b) total time for bowel care, (c) technique/position, and (d) character of results, was nonexistent before T3. After guideline implementation/dissemination (T2 vs. T3), compliance increased significantly to 41% overall (ranging from 11% to 80% across the 6 sites, P ≤ 0.001). Adherence rates increased at all 6 sites.

Recommendation #30/31a: Bowel Management Education

Rates of adherence increased slightly between phases, but these increases were not statistically significant. Rates of adherence were essentially unchanged between phases but increased slightly at 5 of the 6 sites by T3.

Recommendation #30/31b: Bowel Management Competence

Rates of adherence were essentially unchanged between phases but increased at all 6 sites by T3.

Assessment of Neurogenic Bowel Outcomes

For the primary determination of outcomes, we assessed whether individuals who were eligible for guideline recommended care experienced any of the neurogenic bowel management adverse events, by using Veteran Affairs administrative data. We identified a number of shortcomings of Veteran Affairs administrative data for assessing neurogenic bowel outcomes. One problem we encountered was that Veteran Affairs only began collecting diagnostic information for outpatient clinic visits in 1997. Thus, we would have been able to use outpatient diagnoses for only 2 of the 3 time periods. In addition, we learned that many of the outcomes of interest for neurogenic bowel were not always reliably collected. For example, while we expected that patients hospitalized for treatment of serious problems like bowel obstruction would receive a formal diagnosis in the medical records, some problems were so common among veterans with SCI (eg, hemorrhoids, rectal bleeding, diarrhea, and constipation) that they were not routinely documented in the chart or the administrative data. Another issue encountered was that, although receipt of procedures (especially for colorectal cancer screening) might be documented in the administrative data, the results of the tests were not well documented. As a result, we determined that we could not reliably identify most of the adverse outcomes using administrative data. Because the administrative data identified so few cases, we concluded that this procedure had poor sensitivity, and these data will not be presented.

DISCUSSION

As expected, rates of adherence with most of the measured guideline recommendations did not change significantly between the prepublication (T1) and preimplementation (T2) phases. This is consistent with the findings of others that guideline publication and distribution alone does not result in changes in patient care. However, a targeted implementation strategy was associated with significant increases in adherence to 3 of the 6 measured guidelines in the postimplementation (T3) phase.

Recommendation #2: Content of Patient History/Recommendation #3: Content of Physical Examination

Results for these 2 guideline recommendations are similar. Veteran Affairs SCI providers, which include physicians, physician assistants, and/or nurse practitioners, had moderate rates of documentation of relevant areas of bowel history for veterans with SCI before the targeted implementation strategy. The increase in adherence after implementation suggests that the guideline implementation strategies had some effect toward increasing documentation in this area. However, the percentage change was not large.

Recommendation #4: Assessment of Function

A high rate of adherence was observed for this guideline recommendation in all 3 phases as well. Components required to meet criteria for this guideline would be performed during an initial physical and/or occupational therapy assessment. Nearly all patients with acute traumatic or nontraumatic SCI undergo such assessments at SCI Centers, without respect to guidelines. These assessments would be reflected in discipline specific progress notes and interdisciplinary team documentation.

Recommendation #17: Documentation of Bowel Care Programs

A significant increase in documentation was achieved, most likely as the result of the implementation of a uniform bowel care reporting tool during the implementation/dissemination phase. Nevertheless, overall adherence was still relatively low (40%). While nursing documentation of patient bowel movements is standard practice, the criterion's requirement of all 4 variables probably reduced the percentage reported as positive. Common nursing practice on non-SCI units would likely include date and consistency of bowel movement but would not likely include duration of bowel, methods of stimulation, and patient position for bowel care. In addition, collection of data at a single point in time early in the patient's hospitalization (day 3 or next scheduled bowel care) may have resulted in a lower rate, excluding patients for whom the proper documentation may have occurred later but had not yet been implemented. Nursing time required to complete the bowel care documentation form may have proven a hindrance to adherence.

Recommendation #30/31a: Bowel Management Education/Recommendation #30/31b: Bowel Management Competence

Rates of adherence tended to be high for individual sites at baseline (prepublication), which may have resulted in little room for improvement in adherence. Overall, a high percentage of new injuries were reported as having received education in bowel management during all phases. Most sites reported the presence of a pre-existent structured educational program, documentation of which satisfied this criterion. In addition, patients with acute SCI tend to receive interdisciplinary evaluation and staffing, at which time the Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities (CARF)-mandated documentation of bowel education occurs. One site (data not shown) did report a decrease in education rates related to a change in key nursing education staff, which resulted in decreased documentation of bowel care education.

Limitations

Several limitations were inherent in this study. Most are alluded to in the discussion above. In addition, study sites were not randomly chosen and may not be representative of Veteran Affairs SCI Centers nationwide.

Concurrent developments that we were unable to control for may have had an impact on the results presented here. In 1996, Veteran Affairs began implementing a Preventive Health Screening mandate, and a task force was developed. It is also possible that variability between sites in nurse staffing and/or time constraints for documentation may have resulted in a discrepancy between actual practices and documented practices.

It should be noted that the guidelines for which no significant changes occurred were those (4, 30/31a, and 30/31b) that applied to acute injuries only, resulting in a much smaller number of patients (162 vs 2,703 for chronic injuries). Thus, these analyses may have lacked adequate statistical power.

The national implementation of a computerized patient record system was ongoing across Veteran Affairs at the time of implementation of the interventions of this study. Variability in level of and skills in mastery of the electronic medical record and in types/structures of educational programs between sites could have introduced variability in reported rates of adherence. Increased use of electronic medical records could result in increased capture of existing adherence activity as opposed to a true increase in adherence. Anecdotal data support the latter; a true increase in adherence does occur.

Because we required all aspects of the recommendation be present for provider adherence to be considered “met,” the decision not to provide “partial credit” may have resulted in lower overall adherence rates.

How guideline recommendations are written strongly influences the likelihood of implementation. Michie and Johnson (25) found that providers followed guidelines about two thirds of the time “if they were concrete and precise” but were much less likely to do so when recommendations were “vague and non-specific.” We experienced difficulty in operationalizing adherence, as well as in linking receipt of CPG recommended care to specific outcomes in this study. This feedback was provided to the publishers of the guideline, which should be useful as they prepare to update and revise the guideline.

CONCLUSIONS

This study represents a large multisite clinical trial evaluating the implementation of a CPG, specifically, Neurogenic Bowel Management in Adults with Spinal Cord Injury. We found that passive distribution of the CPG had no significant impact in changing provider behaviors. However, when targeted implementation strategies were implemented (based on barriers that providers identified for implementing the guidelines), adherence to clinical guideline recommendations improved for 3 out of 6. Of the 3 recommendations for which no statistical improvement were noted, 2 methodological flaws may have concealed positive outcomes.

First, guideline recommendations that applied only to newly injured persons with SCI were underpowered to detect changes over time. Second, a ceiling effect was noted, whereby baseline data showed strong adherence, leaving little room for improvement over time. Providers at selected Veteran Affairs SCI units consistently performed bowel management education, competence assessment, and assessment of bowel function for persons with acute SCI; this was not further increased with efforts to implement clinical practice guidelines.

Given these 2 limitations, we concluded that chart-based reminders were effective in improving provider adherence to guideline recommendations. However, it is not clear whether the providers actually changed their behavior or whether their actions were simply documented more effectively. Further research is needed to measure provider behaviors beyond traditional chart-based reviews to assess this impact.

Very few studies address the use of different oral or rectal medications for bowel care. In addition, bowel management is highly individualized and personal, and symptoms of bowel dysfunction vary widely among individuals. Studies attempting systematization and uniformity of bowel evacuation interventions are lacking. Our results support the need for additional research in this area. There is a great need to perform such studies, across large numbers of individuals with SCI, to establish best practices for inclusion in future guideline recommendations.

Further research regarding the effectiveness of interventions and medications for management of neurogenic bowel are needed to allow refinement of existing CPGs. Further research is also needed to examine effective strategies to change provider practices to reflect guideline-recommended care.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the contributions of the following project staff—Project Manager: Barbara Simmons, MSN, RN; Data Abstractors: Shirley Almond (Tampa), Richard Buhrer (Seattle), Elaine Gunby (Augusta), Michael Hallock (San Diego), Jackie McFarlin (Dallas), Lyn Morrison (Miami); Additional Contributors: Judy Gordon, Harriet Bowers (Miami), Paul Thomas (PVA, Washington, DC), Sherri LaVela (Hines), Victoria Martinez (Tampa); Expert Panel Members: Kaye Hixon (Tampa), Barbara Simmons, MS, RN (Tampa), David Chen, MD (Chicago), Frances Weaver, PhD (Hines).

Footnotes

This study was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration (VHA), Clinical Program Initiatives, and Spinal Cord Injury Group for VA Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI), as well as Paralyzed Veterans of America and United Spinal Association. Further support was provided by the VHA Medical Centers in Augusta, Dallas, Miami, San Diego, Seattle, and Tampa.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

REFERENCES

- Hanson R, Franklin M. Sexual loss in relation to other functional losses for spinal cord injured males. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1976;57:291–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roach MJ, Frost FS, Creasey G. Social and personal consequences of acquired bowel dysfunction for persons with spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2000;23:263–269. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2000.11753535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiens SA, Biener-Bergman S, Goetz LL. Neurogenic bowel dysfunction after spinal cord injury: clinical evaluation and rehabilitative management. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1997;78:S86–S102. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(97)90416-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boss BJ, Pecanty L, McFarland SM, Sasser L. Self-care competence among persons with spinal cord injury. SCI Nurs. 1995;12:48–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogh K, Nielsen J, Djurhuus JC, Mosdal C, Sabroe S, Lauergurg S. Colorectal function in patients with spinal cord lesions. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:1233–1239. doi: 10.1007/BF02055170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiens SA, Fajardo NR, Korsten MA. The gastrointestinal system after spinal cord injury. In: Lin V, editor. Spinal Cord Medicine: Principles and Practice. New York: Demos Medical Publishing; 2003. pp. 321–348. [Google Scholar]

- Stone JM, Nino-Murcia M, Wolfe VA, Perkash I. Chronic gastrointestinal problems in spinal cord injury patients: a prospective analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85:1114–1119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malassigne P, Nelson AL, Cors MW, Amerson TL. Design of the advanced commode-shower chair for spinal cord-injured individuals. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2000;37:373–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson A, Malassigne P, Cors MW, Amerson TL. Promoting safe use of equipment for neurogenic bowel management. SCI Nurs. 2000;17:119–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinal Cord Medicine Consortium. Clinical practice guidelines: Neurogenic bowel management in adults with spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 1998;21(3):248–293. doi: 10.1080/10790268.1998.11719536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimshaw J, Russell I. Achieving health gain through clinical guidelines I: developing scientifically valid guidelines. Qual Health Care. 1993;2:243–248. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2.4.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimshaw J, Eccles M, Russell I. Developing clinically valid practice guidelines. J Eval Clin Prac. 1995;1:37–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.1995.tb00006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien MA, Thomson N, Freemantle AD, et al. Continuing education meetings and workshops: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. 2005. Available at: http://www.cochrane.org/reviews/en/ab003030.html. Accessed July 25.

- Davis DA, Thomson MA, Oxman AD, Hayes RB. Changing physician performance. A systematic review of the effect of continuing medical education strategies. JAMA. 1995;274:700–705. doi: 10.1001/jama.274.9.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oxman AD, Thomson MA, Davis DA, Haynes RB. No magic bullets: a systematic review of 102 trials of interventions to improve practice. CMAJ. 1995;153:1423–1431. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Getting Evidence into Practice. Effective Health Care. 1999;2005;5(1):1–16. Available at www.york.ac.uk/inst/crd/ehc51.pdf. Accessed September 20. [Google Scholar]

- Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1995. Using Clinical Practice Guidelines to Evaluate Quality of Care. Volume I: issues. [Google Scholar]

- Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1995. Using Clinical Practice Guidelines to Evaluate Quality of Care. Volume II: methods. [Google Scholar]

- Burns SP, Nelson AL, Bosshart HT, et al. Implementation of clinical practice guidelines for prevention of thromboembolism in spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2005;28:33–42. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2005.11753796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guihan M, Simmons B, Nelson A, Bosshart HT, Burns SP. SCI provider's perceptions regarding feasibility of implementing clinical practice guidelines. J Spinal Cord Med. 2003;26:48–58. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2003.11753661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuritz SJ, Landis JR, Koch GG. A general overview of Mantel-Haensel methods: applications and recent developments. Ann Rev Public Health. 1988;9:123–160. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.09.050188.001011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeger SL, Liang KY, Albert PS. Models for longitudinal data: a generalized estimating equation approach. Biometrics. 1988;44:1049–1060. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch G, Atkinson S, Stokes M. Poisson regression. In: Kotz S, Johnson NL, Read CB, editors. Encyclopedia of Statistical Sciences. New York: John Wiley and Sons Inc; 1986. pp. 32–41. [Google Scholar]

- Michie S, Johnston N. Changing clinical behavior by making guidelines specific. BMJ. 2004;328(7435):343–345. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7435.343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]