Abstract

Background/Objective:

The purpose of this study was to compare patient outcomes and quality of life for people with neurogenic bowel using either a standard bowel care program or colostomy.

Methods:

We analyzed survey data from a national sample, comparing outcomes between veterans with spinal cord injury (SCI) who perform bowel care programs vs individuals with colostomies. This study is part of a larger study to evaluate clinical practice guideline implementation in SCI. The sample included 1,503 veterans with SCI. The response rate was 58.4%. For comparison, we matched the respondents with colostomies to matched controls from the remainder of the survey cohort. A total of 74 veterans with SCI and colostomies were matched with 296 controls, using propensity scores. Seven items were designed to elicit information about the respondent's satisfaction with their bowel care program, whereas 7 other items were designed to measure bowel-related quality of life.

Results:

No statistically significant differences in satisfaction or quality of life were found between the responses from veterans with colostomies and those with traditional bowel care programs. Both respondents with colostomies and those without colostomies indicated that they had received training for their bowel care program, that they experienced relatively few complications, such as falls as a result of their bowel care program, and that their quality of life related to bowel care was generally good. However, large numbers of respondents with colostomies (n = 39; 55.7%) and without colostomies (n = 113; 41.7%) reported that they were very unsatisfied with their bowel care program.

Conclusion:

Satisfaction with bowel care is a major problem for veterans with SCI.

Keywords: Colostomy, Spinal cord injuries, Neurogenic bowel, Bowel care, Quality of Life, Life satisfaction, Activities of daily life

INTRODUCTION

Neurogenic bowel is a term that relates colon dysfunction to a lack of nervous control (1). The consequences of this altered function include factors such as incontinence, urgency, and increased time spent in bowel care (2). Glickman (3) interviewed 115 persons with spinal cord injury (SCI) treated in an outpatient clinic concerning bowel function before and after injury. Fifty percent of the respondents indicated they had at least 1 diagnosed bowel problem after injury, compared with 21% before injury (P < 0.0001). The most commonly reported bowel problem after injury was constipation (30%), followed by hemorrhoids (23%), and nausea (19%). Ninety-five percent reported they required at least one therapy method to initiate defecation, 50% were dependent on others for bowel care, and 49%took more than 30 minutes to complete bowel care. Fifty-four percent indicated that bowel function was a source of distress in their lives. Finally, bowel management is recognized as an area of “least competence,” ie, an area that persons with chronic SCI and their families find difficult to manage successfully (4).

Because neurogenic bowel and the related bowel care problems are so common among persons with SCI, a bowel care management program is typically prescribed. The term, bowel care management program, refers to that structured program necessary for successful management of the neurogenic bowel. It typically has 2 components: (a) oral agents, such as laxatives, stool softeners, and fiber (dietary or medication); and (b) a “trigger” administered rectally, such as digital stimulation of the anal sphincter, manual evacuation, suppositories, or enemas. To facilitate social continence, people with SCI and neurogenic bowel are encouraged to complete their bowel care program on a scheduled basis, typically every other day or 3 times per week.

In some patients, a colostomy may become necessary. The SCI-specific factors that are most likely to lead to a colostomy are bowel perforation caused by fecal obstruction and the need to maintain a clean perineum because of an ischial or sacral pressure ulcer. Other non-SCI–specific factors that might lead to a colostomy include ischemia (atherosclerotic), diverticulitis, or carcinoma. In addition, some persons with SCI and/or their caregivers may choose colostomies for ease of care. Persons with coexisting SCI and colostomies do not perform a bowel management program in the traditional sense, although the routine of managing their colostomies is a type of bowel management. Colostomies do obviate the need for performing a specific routine to achieve elimination; thus, colostomies might seem to be advantageous to the SCI patient. However, few, if any, elect colostomies as a primary tool for management of neurogenic bowel, even though the use of colostomy to treat chronic bowel problems or perineal pressure ulcers has been shown to simplify bowel care, relieve abdominal distention, and prevent fecal incontinence (5).

Kirk et al (6) surveyed 171 adults with SCI concerning their bowel care programs. Duration of injury in the sample ranged from 1 to 44 years, with a mean of 8.9 (SD 8.9) years. Although all respondents reported being on a bowel care program when they were discharged to home, 18% (n = 31) no longer used the program. Mean length of time to perform bowel care was 47 minutes and the median was 20 minutes; however, 14% (n = 20) reported taking more than 1 hour. Because their program had been taking so long, many respondents reported inserting a chemical stimulant at bedtime, sleeping through the night, and then “cleaning up” in the morning. Only 16% of the respondents (n = 22) met criteria for having effective bowel programs. These criteria include bowel elimination that is regular, keeps the patient free of complications, takes no longer than 1 hour to perform, and can be carried out by resources available to the individual. The respondents rated their satisfaction with various aspects of their bowel care program on a scale from 1 (very dissatisfied) to 10 (very satisfied). Respondents were least satisfied with the time (mean = 6.8, SD = 2.9) and effort (mean = 6.9, SD = 3.0) spent on bowel care and most satisfied with cost of bowel care (mean = 8.1, SD = 2.8). Satisfaction scores for respondents with colostomies were higher than those for respondents without colostomies; however, only 5 patients with colostomies responded to the survey.

Several recent studies have specifically investigated the impact that colostomy has on the quality of life for persons with SCI. Rosito et al (7) surveyed 27 patients to evaluate the effects of colostomy on their quality of life. In this study, patients directly compared the frequency of bowel care problems, aspects of their bowel care program, and measures of quality of life before and after colostomy. All patients reported being satisfied with their colostomies, and 59% reported being “very satisfied” with their colostomies. Nineteen (70%) suggested, in retrospect, they would have preferred to have had their colostomies performed earlier. Colostomies were associated with reduced hospitalizations caused by bowel problems, less time spent on bowel care, and increased independence. After colostomy, patients reported statistically significant higher measures in a total quality of life index (P < 0.0001), as well as improvement in physical health (P < 0.0001), self-efficacy (P < 0.0001), psychological status (P < 0.015), and recreation/leisure activity (P < 0.0001) subscales. A domain measure comparing precolostomy and postcolostomy body image remained statistically unchanged, however.

A prospective case-control study was conducted by Randell et al (8), comparing the general well being, and the emotional, social, and work functioning of 26 SCI patients who had colostomies, with matched controls without colostomies. The 2 groups were matched for level of injury, completeness of injury, length of time since injury, age (± 5 years), and gender. Responses were elicited using a written questionnaire and were distributed by mail. In this study, however, no significant differences were found between the 2 groups, leading the authors to conclude that patients with colostomies were no worse off than those without colostomies.

The current analysis is based on data obtained as part of a multi-site study to evaluate the implementation of clinical practice guidelines for SCI. Here we compare patient outcomes and bowel-related quality of life in veterans with SCI who perform bowel care programs with those who had colostomies. Although not specifically designed to investigate the impact of colostomy on bowel care, the data provide a unique opportunity to do so in a large cohort of patients.

METHODS

Questionnaire

A self-administered written questionnaire was designed to help evaluate a program to integrate clinical practice guidelines into the routine operation of Veterans Health-care Administration SCI Centers. The survey questionnaire focused on content from the clinical practice guideline, “Neurogenic Bowel Management in Adults With Spinal Cord Injury,” developed by the Consortium of Spinal Cord Medicine and published by the Paralyzed Veterans of America (9). In this paper, we describe the responses to 7 items designed to elicit neurogenic bowel outcomes, as well as 7 items designed to measure neurogenic bowel-related quality of life.

A closed-ended item format was chosen for the bowel care–related items. Four of the items related to whether the bowel care had been initiated, where the program was started, and whether education was provided to the patient and/or family members. Two items concerned whether the respondent's physician had recommended any changes to the bowel care program in the previous year. Finally, one item was included that concerned the respondent's overall satisfaction with the bowel care program.

The quality of life items were modified from the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (IBDQ) developed by Irvine et al (10). Seven items from the IBDQ were minimally reworded to be appropriate for neurogenic bowel–related problems in persons with SCI. Four items measured the extent to which the respondent's bowel problems affect work and social activities. Seven response categories were provided for these items, ranging from “None of the time” to “All of the time.” A single item concerning “To what extent has your bowel problem limited your sexual activity during the past month,” was also included. This item included 8 response categories. Seven of the response categories ranged from “No sex as a result of bowel problem” to “No limitation as a result of bowel problem.” The eighth response category for the questions related to sexual activity was “No sexual activity.” A single item, “How satisfied, happy, or pleased have you been with your personal life in the last month?” was included on the questionnaire. Response categories for this item ranged from “Very dissatisfied, unhappy” to “Extremely satisfied, could not have been more happy or pleased most of the time.” Finally, a single item, “How much time during the last month have you been troubled by unplanned bowel evacuations?” was included. Seven response categories were provided for this item ranging from “None of the time” to “All of the time.”

Responses for each item were assigned scores from 1 (poorest quality of life) to 7 (best quality of life). Respondents answering “No sexual activity” were treated as if they were not applicable and excluded from the scoring. A summary score was calculated for each respondent by adding the values assigned (1 to 7) and dividing the total by the number of items completed. Thus, all scores ranged from 1 to 7, with higher scores indicating “higher or better” quality of life.

Respondents were also asked to provide information about the year they were injured and their social security number. Reported social security numbers were matched against Veteran's Administration (VA) administrative databases to identify additional demographic information, including gender, age, race/national origin, and marital status of the respondents.

Five professionals in the field of SCI reviewed the draft questionnaire to establish content validity. Further, the questionnaire was pilot tested with 20 patients and 10 professionals at a VA SCI facility that was not included in the study. The participants in the pilot study were asked to fill out the questionnaire twice, with approximately 1 month between administrations. Preliminary item analysis was conducted and revisions were made in the questionnaires as needed. Item analysis was repeated with data from the pretest mailing and provided additional support for the items. Internal consistency reliability, as measured by Cronbach α, was 0.85 for the bowel-related quality of life items.

Sample

The survey was conducted among patients in 6 centers that were selected to be representative of the 23 VA SCI centers. All veterans (n = 2,946) who were exposed to guideline-based treatment at a participating institution were mailed a questionnaire before the interventions designed to promote the use of guidelines. A total of 374 questionnaires were returned as undeliverable (the respondent moved, died, etc.), resulting in 2,572 potential respondents. A total of 1,503 usable questionnaires were obtained, resulting in a response rate of 58.4%. Of these, 88 were completed by veterans with colostomies. For the purpose of comparison, we matched the respondents with colostomies to controls from the remainder of the survey cohort. We simultaneously matched the respondents with controls based on age, year of injury, classification of paralysis, and marital status by calculating propensity scores (10). Propensity scores are based on the results of regression models that provide and represent a best linear combination of the matching variables. One disadvantage of this method is that matches can only be accomplished for cases with valid data for all of the matching variables. Fourteen out of the 88 patients had missing values on at least one of the variables used for matching and were excluded from the analysis. In this study, we compare the responses of the 74 patients with a sample of 296 matched controls (4 matches for each control) of patients without colostomies.

Data Management and Analysis

Data entry was completed using optical scan forms (Teleform) for closed ended items included on the questionnaire. A random sample of 20 questionnaires was chosen to compare the results of the scanning and original hard copy. No evidence of error caused by the scanning process was found. Data were analyzed using the SPSS 10.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) and SAS 8.1 (The SAS Institute, Cary, NC). To control for violations of experiment-wide error rates that may occur when simultaneous multiple statistical inferences are conducted, a modified Bonferroni approach was taken to adjust the nominal α level (P < 0.05) for effects of multiple statistical inferences (12).

Respondent Demographics

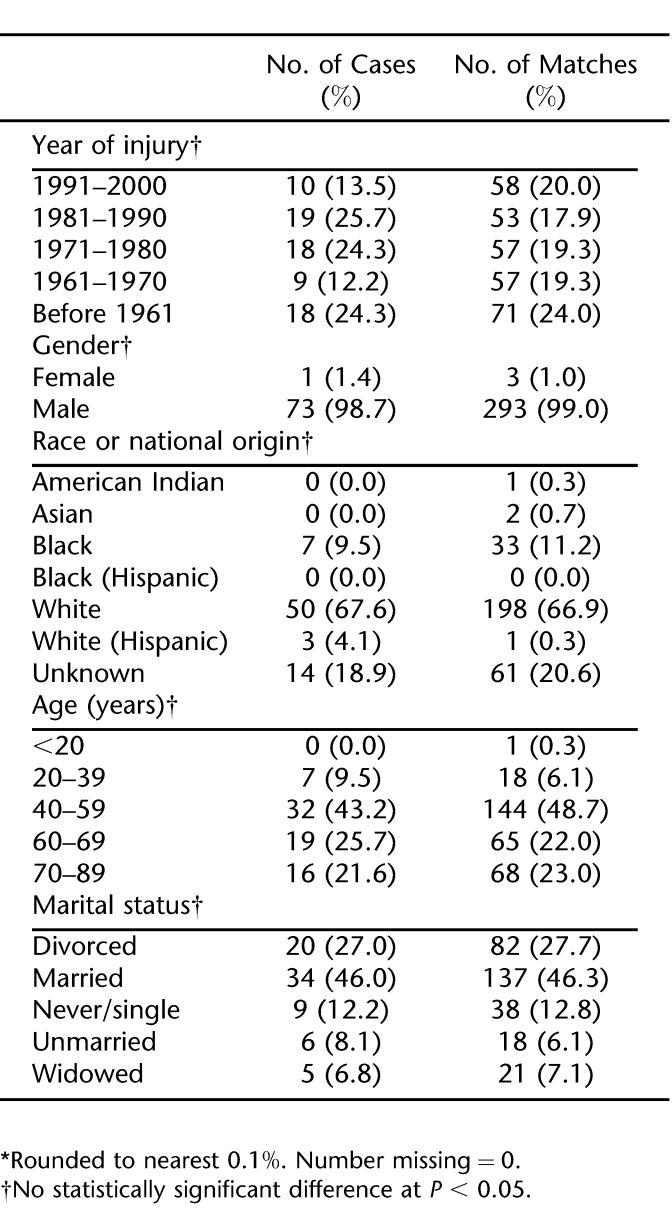

Table 1 outlines the respondents' sociodemographic characteristics. The matching process identified respondents without colostomies who were very similar to those who had colostomies. Approximately 40% of the cases (n = 29; 39.2%) and matches (n = 111; 37.9%) reported having been injured within the past 20 years. Almost all of the respondents were male (n = 73; 98.7% for cases and n = 293; 99% for matches) and white (n = 50; 67.6% for cases and n = 198; 66.9% for controls). Approximately 43% (n = 32) of the cases and 48.7% (n = 144) of the controls were between the ages of 40 and 59 years. Almost half of the respondents were married, for both cases (n = 34; 46%) and controls (n = 137; 46.3%). No statistical significance differences were found in the demographic distributions for cases and controls.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Background of Respondents *

Bowel Care–Related Items

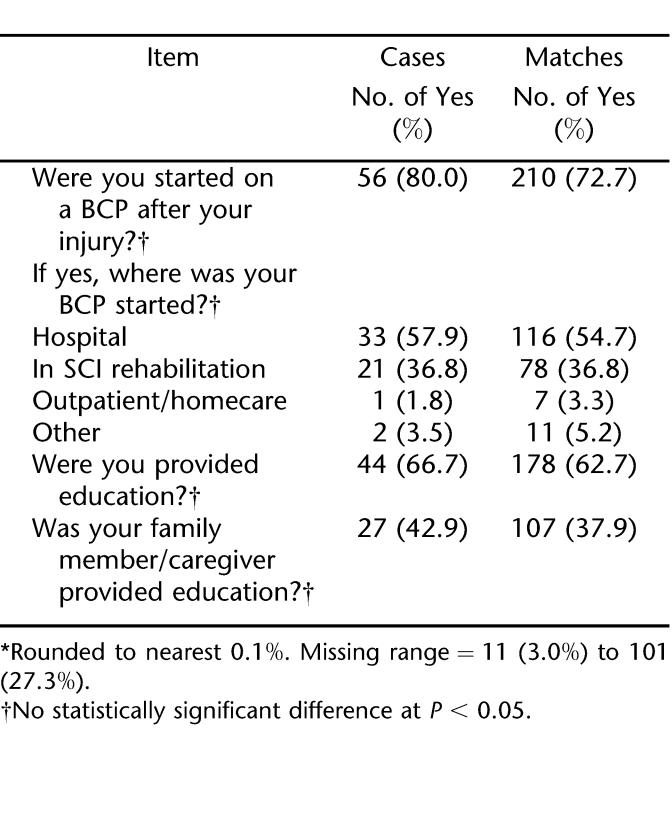

Table 2 describes the responses to items from the questionnaire relating to the initial bowel care program, education about the bowel care program, and staff involved with answering questions about the bowel care program. Most respondents indicated having been started on a bowel care program after their injury (n = 56; 80% for cases and n = 210; 72.7% for controls). Among cases, more than half (n = 33; 57.9%) indicated that they were started on their program in acute care, whereas 36.8% (n = 21) reported being started in the SCI rehabilitation setting. Similar patterns were found in controls. Forty-four cases (66.7%) and 178 matches (62.7%) indicated that they had received education about their bowel care program. Approximately 43% (n = 27; 42.9%) reported that their family had been trained, compared with almost 38% for controls (n = 107).

Table 2.

Items Relating to the Development of and Training About the Bowel Care Program (BCP) *

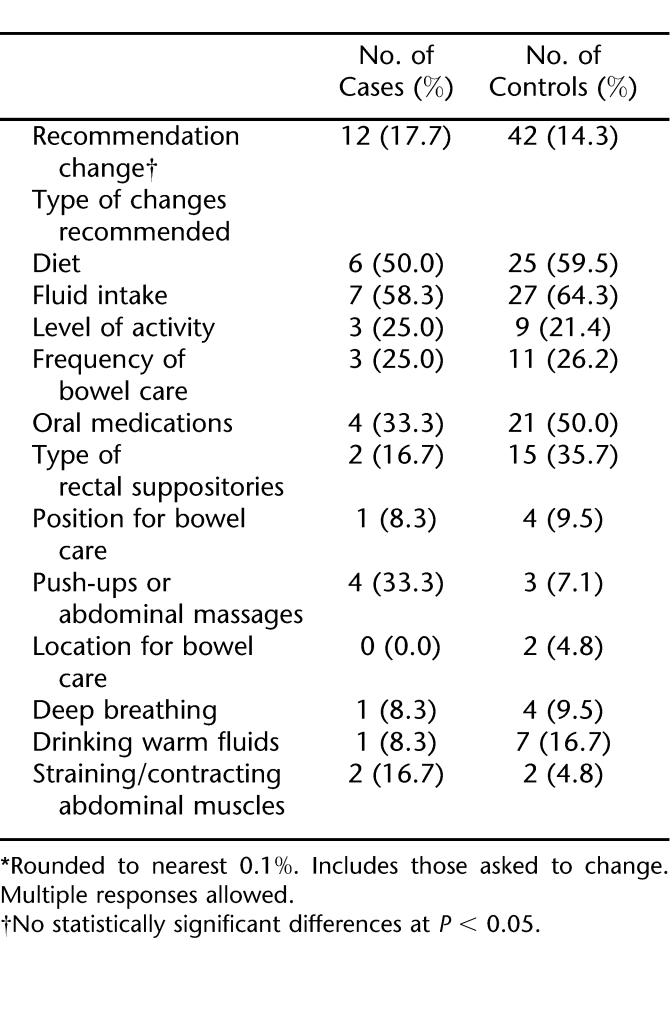

Table 3 shows that 12 cases (17.7%) and 42 matches (14.3%) indicated that their doctor or nurse had recommended that they change their bowel care program in the last year. Of those being asked to change their program (Table 3), the most common recommendation was an increase in fluid intake for both cases (n = 7; 63.6%) and matches (n = 27; 64.3%); followed by a change in diet in 6 cases (50.0%) and 25 matches (59.5%); and addition of oral medications in 4 cases (33.3%) and 21 matches (50%). Overall, the recommendations for change in diet were very similar, with no statistically significant differences being found.

Table 3.

Recommended Changes in the Last Year *

Three items were included that elicited information about adverse events associated with bowel care. In the first item, respondents were asked whether, “In the last year, have you had problems with pressure ulcers due to the use of bowel equipment, such as a bowel care chair?” Eleven percent of the cases (n = 5) and 9.5% of the matches (n = 22) responded yes to this item. The next item asked respondents, “In the last year, have you had a fall while performing your bowel care program (transfer to toilet or from bowel equipment)?” Approximately 8% (7.7%; n = 5) of the cases and 6.1% (n = 17) of the matches reported having fallen. Finally, respondents were asked to report how many “ accidental (unplanned) bowel movements, do you have in one month?” Again, the responses were similar for the 2 groups. Patients with colostomies reported an average of 5.0 (n = 49; SD = 13.3) accidental bowel movements, a mean of 2.8 (n = 251; SD = 10.0) accidents. None of the differences reported in this section were statistically significant.

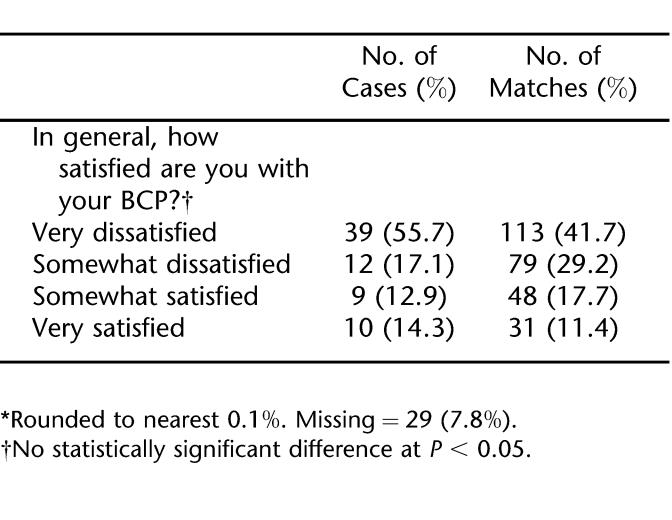

Respondents were asked, “In general, how satisfied are you with your bowel care program?” Nearly 30% of both the cases and the controls indicated that they were “Somewhat satisfied” or “Very satisfied” with their bowel care program (Table 4). The cases had a much higher percentage of responses (n = 39; 55.7%) in the “Very dissatisfied” category than did the controls (n = 113; 41.7%). Overall, there were no statistically significant differences between cases and controls regarding their satisfaction with the bowel program.

Table 4.

Satisfaction with Bowel Care Program (BCP) *

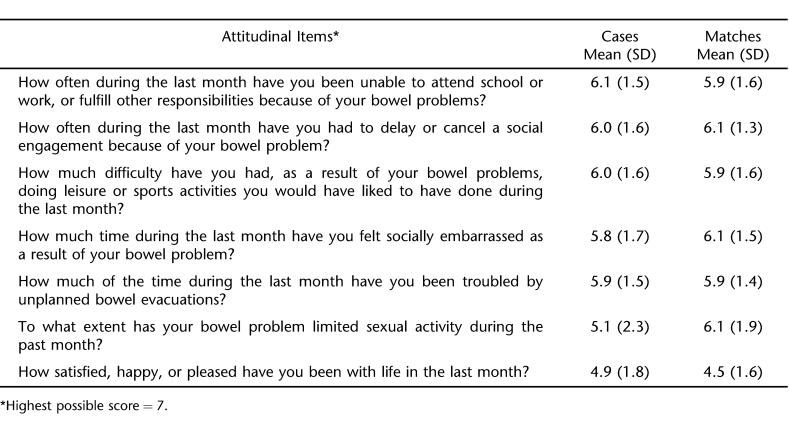

Quality of Life Items. Both veterans with colostomies and the matches reported relatively good bowel-related quality of life, with mean scores for the individual items ranging from 5.1 to 6.2 out of a possible 7 (Table 5). The largest difference occurred in the items related to whether bowel problems limited sexual activities, with respondents with colostomies reporting a mean score of 5.1 (SD = 2.3) and matched controls answering more positively with a mean of 6.1 (SD = 1.9). However, this difference was not statistically significant after controlling for experiment-wise error. No significant statistical differences were found for any of the other quality of life items. A score of 5 would relate to the response option of “a little limitation as a result of bowel problem,” whereas a score of 6 would relate to the response option “hardly any limitation as a result of bowel problems.”

Table 5.

Bowel-Related Quality of Life Items

DISCUSSION

The data used in this analysis came from a survey conducted as part of a large study to promote the use of clinical practice guidelines in VA Spinal Cord Centers. Although not specifically designed to investigate the impact of colostomy on bowel care outcomes, the large number of responses by patients with colostomies (n = 88) provided a unique opportunity to investigate this issue. In fact, even after eliminating cases for which matches could not be identified, these data represent responses from nearly 3 times as many respondents as recently published reports on this topic (7,8).

Although the size of our sample indicates strength of our study, there are several weaknesses that should be noted. The study questionnaire was not specifically designed to compare outcomes between persons with colostomies and those without. Therefore, several of the item formats and questionnaire structures used limited our analysis. For example, the respondents were asked whether they had a colostomy, rather than if they had a colostomy for treatment of bowel-related problems. Some of our respondents with colostomies may have had their surgeries before their SCI. Although we think this scenario is unlikely, it might have an impact on our results. A perhaps more important example of how the questionnaire might have been structured differently if it were specifically designed to measure the impact of colostomy relates to items designed to document the time spent on bowel care. Because the questionnaire was designed to investigate issues related to bowel care in patients without colostomy, individuals with colostomies were instructed to skip this item. Because of this strategy, we are unable to compare results on this important issue. Based on previous research, it is likely that our respondents with colostomy would spend significantly less time in bowel care than those without.

The principal finding of this study is that there were no statistically significant differences in bowel-related outcomes measured and quality of life in SCI veterans with and without a colostomy. Results of our study run contrary to conventional wisdom that a colostomy results in adverse outcomes for persons with SCI and should only be considered as a treatment of last resort. These results do, however, coincide with the results reported by Randell et al (8), who found no differences between quality of life in persons with colostomies and matched controls. Further support of the positive impact of colostomy is provided by Rosito et al (7), who studied SCI patients with colostomies and asked them to compare their satisfaction with bowel care before and after surgery. In this study, 100% (n = 27) were satisfied or very satisfied with their bowel care. Nineteen of the respondents (70%) indicated that they would have preferred to have the surgery earlier. Persons with colostomies were also found to have 70% fewer hospitalizations caused by chronic bowel dysfunction, and to reduce the average time spent in bowel care from 117.0 min/d to 12.8 min/d.

Interestingly, the respondent's scores were relatively high on the majority of the items measuring bowel-related quality of life. Mean responses to these items suggested that bowel problems had an effect on quality of life “A little of the time” or “Hardly any of the time.” They also indicated that they were “Satisfied most of the time, happy” with their life in the past month. However, respondents expressed relatively low satisfaction with their bowel care program, with more than 40% in each group reporting being “Very dissatisfied” with their bowel care program. This suggests that although bowel care is seen as inconvenient, the problems related to bowel do not prevent the respondents from daily activities.

Patients must give consent before a medical/surgical procedure. For consent to be informed, the risks and benefits of the procedure and its alternatives must be discussed. In an area that affects self-image as much as colostomy, the risks and benefits include not only strictly medical or surgical issues, but also information about the subjective experiences of other patients who have undergone the procedure. Results of this study can provide a framework for such a discussion.

CONCLUSION

This study reports the results of a survey of 74 persons with SCI and colostomies and nearly 300 matched controls. To our knowledge, it represents the largest study sample used to explore this topic. No statistically significant differences were reported between the cases and the matched controls for any of the bowel care outcomes or bowel-related quality of life items included in the study. Both cases and matched controls reported similar experiences with training in bowel care and recommended changes in bowel care during the previous year. Both groups reported low incidence of accidental/unplanned bowel movements and falls related to bowel care. Mean responses to the quality of life items included on the questionnaire were generally very high; however, a large number of respondents continue to express dissatisfaction with bowel care. These results support the contention that among persons with SCI, those who have colostomies and those who practice standard bowel care have similar experiences with bowel care and quality of life related to bowel care.

Acknowledgments

The investigators acknowledge the following individuals for their role in this project: Helen Bosshart, MSW (Augusta VAMC), Harriet Bowers, RN (Miami VAMC), Stephen Burns, MD (Seattle VAMC), Kevin Gerhart, MD (San Diego VAMC), and Barbara Simmons, MSN, RN (Tampa VAMC).

Footnotes

The research reported here was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, as New Program Initiatives #98–009. The Spinal Cord Injury Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI), Paralyzed Veterans of America, and United Spinal Association, and the Consortium for Spinal Cord Injury Medicine provided additional funding and support.

REFERENCES

- Stiens SA, Bergman SB, Goetz LL. Neurogenic bowel dysfunction after spinal cord injury: clinical evaluation and rehabilitative managment. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1997;78(3 suppl):S86–S102. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(97)90416-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch AC, Wong C, Anthony A, Dobbs BR, Frizelle FA. Bowel dysfunction following spinal cord injury: a description of bowel function in a spinal cord-injured population in age and gender matched controls. Spinal Cord. 2000;38(12):717–723. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glickman S, Kamm MA. Bowel dysfunction in spinal-cord-injury patients. Lancet. 1996;347:1651–1653. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)91487-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boss BJ, Pecanty L, McFarland SM, Sasser L. Self-care competence among persons with spinal cord injury. SCI Nurs. 1995;12:48–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone JM, Wolfe VA, Nino-Murcia M, Perkash I. Colostomy as treatment for complications of spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1990;71(7):514–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk PM, King RB, Temples RT, Bourjaily J, Thomas P. Long-term follow-up of bowel management after spinal cord injury. SCI Nurs. 1997;4(2):56–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosito O, Nino-Murcia M, Wolfe VA, Kiratli BJ, Perkash I. The effects of colostomy on the quality of life in patients with spinal cord injury: a retrospective analysis. J Spinal Cord Med. 2002;25(3):174–183. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2002.11753619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randell N, Lynch AC, Anthony A.D, Dobbs BR, Roake JA, Frizelle FA. Does a colostomy alter quality of life in patients with spinal cord injury? Spinal Cord. 2001;39:279–282. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consortium for Spinal Cord medicine. Clinical practice guidelines: neurogenic bowel management in adults with spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 1998;21(3):248–293. doi: 10.1080/10790268.1998.11719536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvine EJ, Feagan BG, Wong CJ. Does self-administration of a quality of life index for inflammatory bowel disease change the results? J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49(10):1177–1185. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(96)00136-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith HL. Matching with multiple controls to estimate treatment differences in observational studies. In: Raferty AE, editor. Sociological Methodology. Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell; 1997. pp. 325–353. [Google Scholar]

- Hochberg Y. A sharper Bonferroni procedure for multiple tests of significance. Biometrika. 1988;75:800–803. [Google Scholar]